Like the inverse of the mythical butterfly flapping its wings in China, an ice core extracted from Greenland can reveal the rise and fall of societies in European antiquity. A new study took ice cores from the Greenlandic ice sheet and used them to measure the output of lead pollution in Europe. The varying levels of lead pollution corresponded with technological and societal changes.

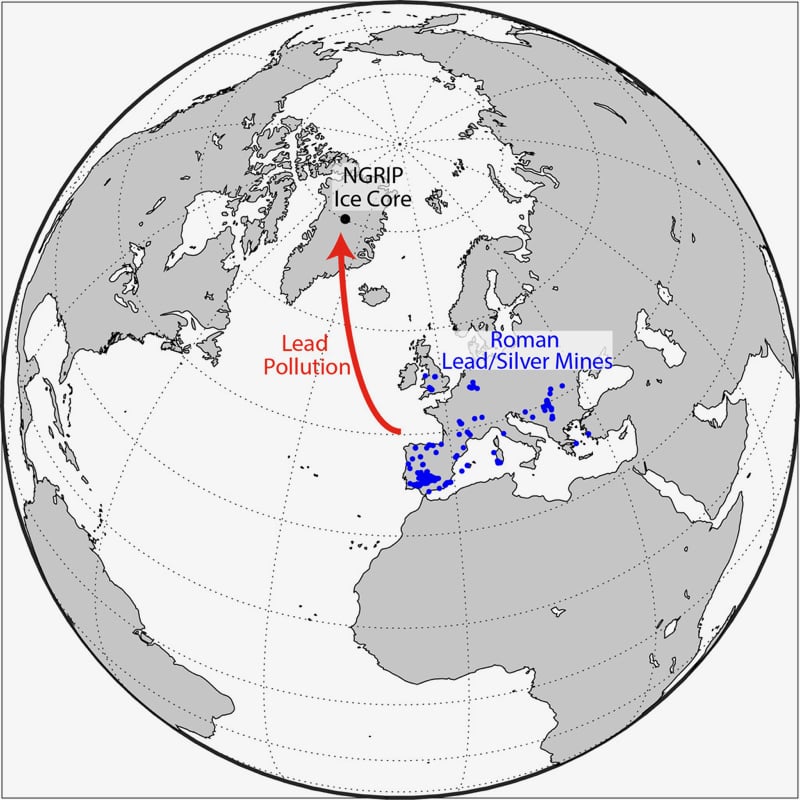

This map illustrates the geographical relationship between ancient lead mines and Greenlandic ice. Photo: Desert Research Institute

A global record

Ice sheets are laid down over time in layers of compacted snow. A bit like tree rings, the conditions during their formation are preserved in the layer.

By taking an ice core, scientists are effectively looking at a timeline of climate conditions over thousands of years. Air temperature, greenhouse gases, pollen levels, and chemical concentrations are printed in the layers.

This latest research is a collaborative effort between several universities and climate research organizations. The ice cores in question come from the North Greenland Ice Core Project, or NorthGRIP. NorthGRIP drilled from surface to bedrock in northern Greenland. While NorthGRIP finished drilling in 2004, the wealth of data it offers is still largely unexplored. Led by Joseph R. McConnell of the Desert Research Institute, researchers recently turned to lead levels.

When we imagine ancient coins, many of us imagine gold, but silver was far more common in most premodern coinage systems. Premodern silver smelting produced a lot of lead pollution, and archaeologists can measure ancient economic productivity through lead levels — more lead, more coins, more activity.

Now only available through the Wayback Machine, the NorthGRIP team took many photos of their work and daily life at a remote Arctic research outpost. This shot shows a team member processing a section of ice core in the drill tunnel. Photo: NGRIP/Departement of Geophysics, Niels Bohr Institute, University of Copenhagen

What your lead poisoning says about you

Wind blows European lead emissions to Greenland, where they freeze in ice. Previous studies worked from limited samples; by using the NorthGRIP ice cores, researchers were finally able to construct a complete record of classical emissions.

The first jump in lead levels came around 1000 BCE, when the Phoenicians began expanding into the Mediterranean. Emissions continued through the founding of the Roman kingdom and then the Republic. Levels spiked again when both the Romans and Carthaginians colonized Spain and began mining silver intensively there.

Both Punic Wars saw short-term declines, as the campaigning in Spain pulled workers away from the mines and to the battlefields. They bounced back quickly as Rome took Spain and began minting Roman silver coins in Carthaginian mines.

Researchers can chart the whole of Roman history in this way. Wars and political crises lead to dips, and with new conquered territory, mining ramped back up. The peak was the Pax Romana, following the ascendance of Augustus née Octavian.

Silver coins minted in 18 BCE, depicting Emperor Augustus, who was known to wear lifts in his shoes to seem taller. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Putting Edward Gibbon out of a job, the ice cores also document the decline and fall of the empire. “The great Antonine Plague struck the Roman Empire in 165 AD and lasted at least 15 years. The high lead emissions of the Pax Romana ended exactly at that time and didn’t recover until the early Middle Ages, more than 500 years later,” explained coauthor Andrew Wilson, of Oxford.