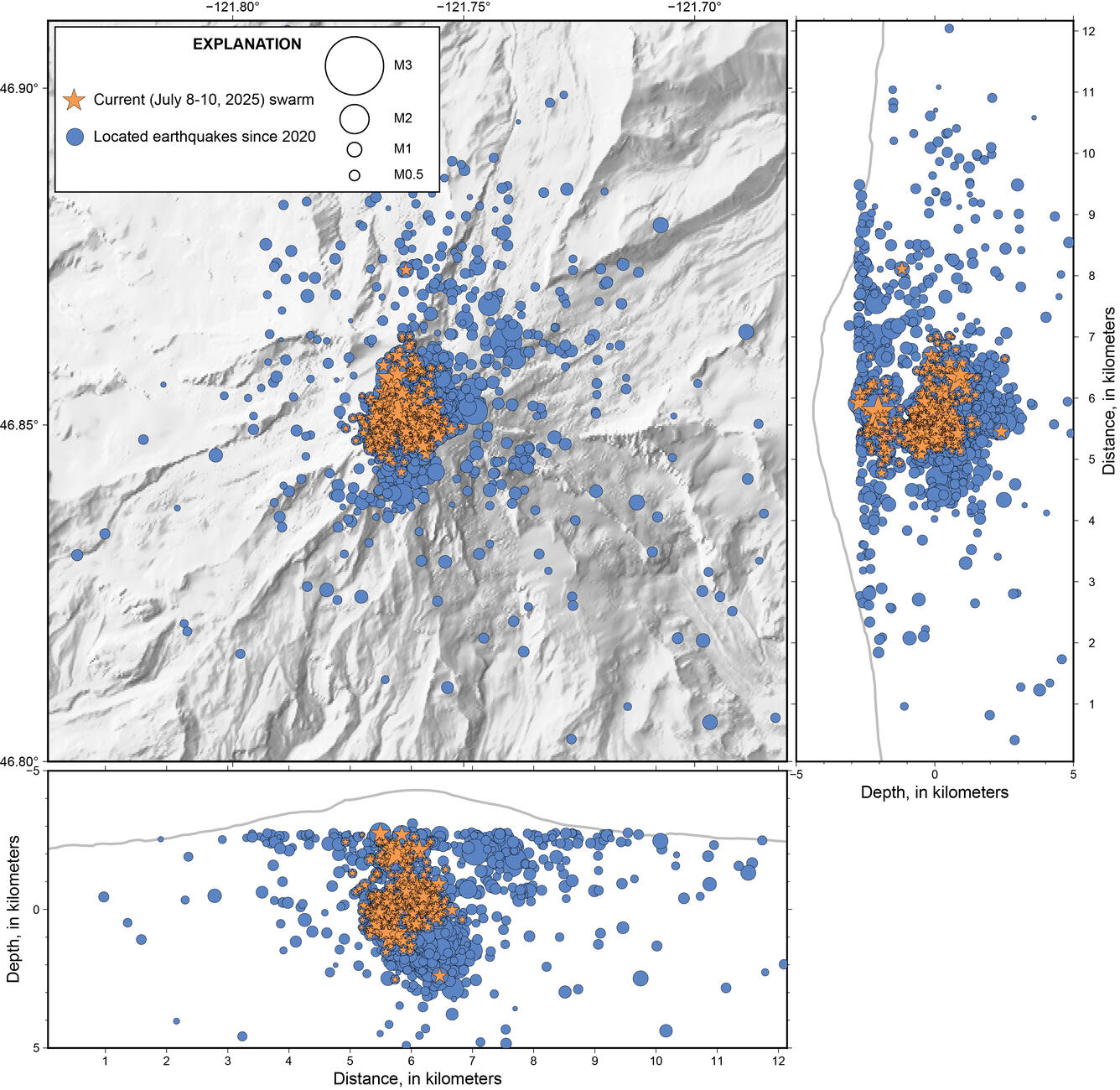

Officials at the United States Geological Survey have tracked over 300 earthquakes beneath Washington State’s Mt Rainier from July 8-10.

A popular tourist destination, Mt Rainier is also an active volcano, closely watched by experts. On average, the area experiences nine small earthquakes a month. About once a year, activity will increase and become a “swarm.” But these regular annual swarms are not nearly as strong as the current event.

The current swarm kicked off between 1 and 2 in the morning, local time, on July 8. The largest quake came twelve hours later, registering 2.3 on the Richter scale. The strength and frequency of the quakes have steadily decreased since. The Pacific Northwest Seismic Network continues to track the miniature earthquakes.

Maps showing the location and frequency of recent earthquakes on Mt Rainier. The current swarm is indicated with gold stars, while the rest of the quakes from 2020 to the present are blue dots. Photo: USGS

Much stronger than the 2009 swarm

The 2025 event has far outstripped the most recent big swarm, from 2009. Scientists detected 120 earthquakes in 2009, and the current swarm is approaching 350, at least 55 of which have been over 1.0 magnitude.

However, officials aren’t concerned yet. The volcano alert level remains at “Green/Normal,” with no danger to hikers. None of the earthquakes, individually, has been big enough to cause any damage, or even felt by visitors to the mountain.

Volcanic disruption is far from the only cause of seismic activity. Rockfalls and landslides can register as seismic events. Glacial movement is another potential contributor, especially since Mt Rainier is the most glaciated peak in the lower 48. Officials believe the recent activity is the result of water moving through preexisting fault lines, above the magma in Mt Rainier.

Just because this level of activity is higher than what we’ve previously observed doesn’t mean it’s abnormal. “We’ve only been monitoring it for 40, maybe 50 years now. So just because it’s the most significant one we’ve seen on equipment doesn’t mean this hasn’t happened in the past,” cautioned Alex Iezzi, a geophysicist with the Cascades Volcano Observatory.

The previous eruption of Rainier was over one thousand years ago; we have a limited understanding of what normal looks like. From that perspective, the swarm is good. It will give researchers an opportunity to learn more about how the volcano works and what we can expect it to do in the future.