In 1981, today’s most-pervasive avalanche rescue technology only existed as an emerging solution to detect tumors.

RECCO arrived in the avalanche safety world thanks to one man who’d lost a friend in the alpine. And it did so quietly — the earliest receivers only produced a peep on transponders from about a meter away. They were too cumbersome to be practical in the field and clearly too limited to make an impact on rescues.

Fast forward 40 years to today, and RECCO reflectors are virtually everywhere. Signals cut through 20 meters of snow or 80 meters of air.

It’s elementary that mountain rescue looks different now than it did then. But is it more effective?

1,643 victims

That was the inquiry in one broad, recent survey of avalanche rescues in Switzerland from 1981-2020. In it, lead author Simon Rauch and his colleagues comb through 1,643 avy disaster records in search of patterns. The authors broke the data down into two sets: the period from 1981-1990 and the overall period (1981-2020).

They discovered that rescues got faster and survival rates climbed overall. And though emergency responders are far faster now than in the ‘80s, you’re still significantly better off if your own team comes to your aid.

Generally, a “critical avalanche burial” (like those in the study) occurs when a victim’s head and chest are completely buried in snow. For obvious reasons, these avalanche subjects benefit from fast rescues. Disregarding all other circumstances or injuries, a human trapped in avalanche pack snow can suffocate in 15 minutes.

In avy rescue, speed has always been the name of the game. And operations that took 10 minutes or less “remained high” in success rate throughout those 40 years of data, the report found. Survival at 130 minutes or more also increased.

Companion rescues averaged 15 minutes from 1981-1990. The average drops to 10 minutes over all four decades. Rescue professionals sped up significantly more: down to 90 minutes on average from 153 minutes.

Overall survival increased slightly.

- From 1981-1990, 43.5% of victims survived.

- During the entire study period, 53.4% survived.

The report stopped shy of correlating results with specific activities, instead pointing to improvements in field techniques and medical technology.

And Mother Nature still makes the rules. Every avalanche rescuer, the report urged, should work fast.

“In this study, the risk of dying from suffocation between 10 and 30 minutes of burial remained unchanged over the past four decades," it cautioned, "highlighting the greatest challenge in the search and rescue of [buried] individuals...The time window for a successful rescue is short and should be considered by all educators, stakeholders, and manufacturers of avalanche safety equipment.”

Here’s the deal: If you want visual stimulation and alpine drama, look elsewhere in a climbing documentary. But if you want a dense mountain report from an ambivalent veteran, immune to travails that could force lesser souls to the brink, keep watching.

Colin Haley’s 2023 solo bid on the Supercanaleta, a Fitz Roy masterpiece that loosens the bowels of even the staunchest climbers, is as simple as that. Haley doesn’t feel sorry for himself, wears the anachronistic facial sun shades, and executes a laborious and impressive ascent.

While filming himself.

Here’s a tidbit from one of the alpine world’s most stoic customers in the high alpine:

"I’m kinda just physically and mentally fried a bit. I kind of think this super-intense, stressful stuff is not for me anymore. [But] even just bailing from here is definitely going to be a very long journey. It’s something like 4,000 feet of rappelling from here to the ‘schrund."

Stick around for an incisive self-inventory in the meadow below. Spoiler alert: don’t bet against my guy.

Amity Warme is tough. It’s no surprise she’s willing to take a big, complicated, 25-pitch bite out of El Capitan the old-fashioned way.

Watch Warme and Brent Barghahn do just that in Ground Up. Arc’teryx chronicles the two penitents on an old-fashioned "ground up" attempt on El Capitan’s El Niño (Pineapple Express variation, 5.13b/c).

It’s a characteristic outing for Warme who, Alex Honnold assesses, "brings a little bit of that old-school mountaineering vibe to modern performance rock climbing."

Power screams and physical-limit climbing

The ascent comes off as a modern foray into the canon of rock climbing — ground-up style, or climbing without rappelling or scouting pitches, is the oldest way to climb El Capitan. It used to be the only accepted way and didn’t become possible in free climbing until several generations of climbers had tangoed with the wall.

If you like a try-hard, you’ll appreciate this pair’s effort. Hang on tight for power screams, physical-limit climbing through clouds and rain showers, and plenty of roof-wrangling.

Murphy’s Law doesn’t quite descend over the climbers like the Yosemite Valley storms do. But this eight-day siege is an adventure by definition, and the team grapples with unexpected and uncontrollable events.

It’s a mixed bag. One thing you won’t find in it, though? Ask Warme.

"You know what they say — excuses are like buttholes," she quips. "Everyone’s got one and no one wants to hear yours."

Message received.

In September 2023, a bizarre wave of concentrated seismic upheaval reverberated across the planet for nine days.

The quake baffled seismologists. Most seismic signals are chaotic and brief. These were concerted and prolonged, like sonic energy from "a big musical instrument," Stephen Hicks, a seismologist at University College London, told Science.

Why?

While there’s still no answer to every question about the nine-day event, researchers now think they’ve discovered its primary cause.

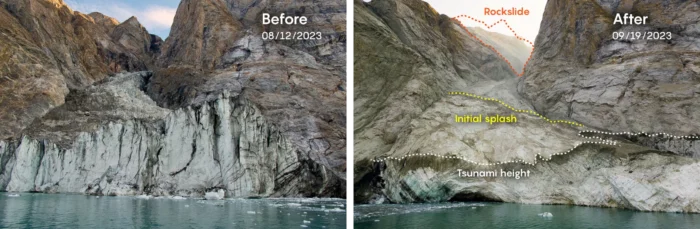

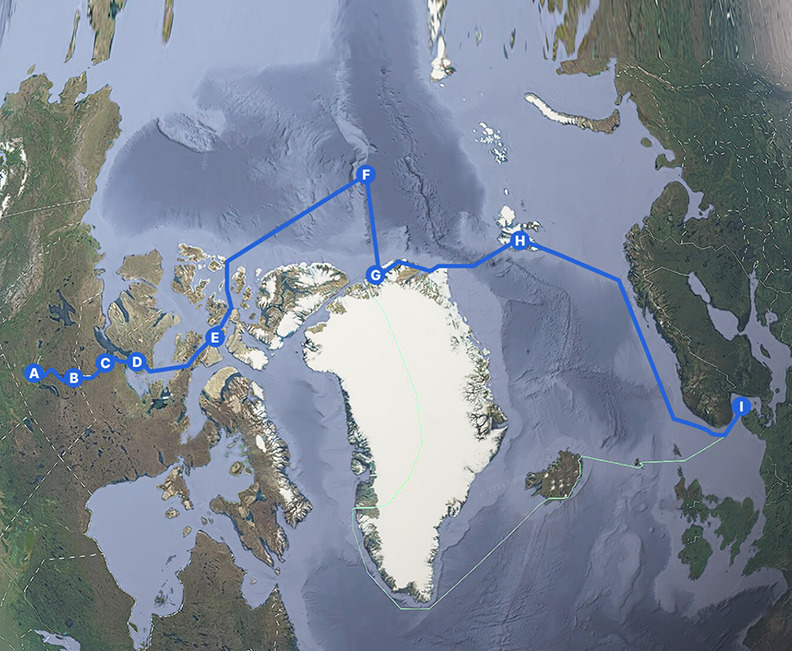

In a yearlong study published this month, Hicks and 67 co-authors spell out how a rockslide in a Greenland fjord caused a local tsunami that triggered the worldwide echo. The research demanded a concerted effort between local sources and seismology field leaders scattered across the globe.

On Sept. 16, 2023, an enormous chunk of ice and rock cut loose from a glacier bed above eastern Greenland’s Dickson Fjord. The slide measured some 25 million cubic meters, about 10 times the volume of the Great Pyramid of Giza, Quanta Magazine reported. It tore through the glacier bed and wiped out historic Inuit archaeological sites and 20th-century trapper hunts.

When it escaped out the glacier’s mouth at 160kmph and thundered into the ocean, the splash was immense. Waves crested at 200m and flooded a military outpost on Ella Island, 72 km away. (Quanta reported nobody was injured or killed, but that the island is now "far smaller.")

The event shook the planet. Instruments built to detect secret nuclear weapons tests registered it in Russia, 3,300 km away.

Then the strange humming phenomenon began.

Trapped wave?

Seismic signals usually dissipate reliably because of the laws of physics and basic inertia. Waves eventually weaken as they broadcast, feedback decreases, and the disturbance settles out. But in this case, seismic waves kept echoing across the planet, despite a Danish navy survey three days after the collapse that found no further disturbance.

Detective work into subterranean phenomena commenced. One theory was that the concussion might have caused significant ice melt, which then forced water through natural caverns under the glacier. This could turn the glacial piping into the geological equivalent of a musical instrument.

But eventually, the 68 scientists landed on a prevailing theory: a seiche wave.

In a seiche wave, water gets trapped in wave motion, bouncing back and forth in a contained space. It’s common in lakes and harbors. One seiche wave in Lake Erie, Michigan swept several beachgoers into the water in 2013.

However, multiple angles of inquiry failed to substantiate the theory, including an experiment in one scientist’s bathtub. Finally, computer modeling with equipment from the Danish navy persuaded the group. Water in a seiche wave could only escape Dickson Fjord gradually, via small channels, so a wave could get trapped for longer than average.

Amazingly, the researchers found that the wave had depleted to just a few centimeters high after three days. That was strong enough to continue the "song" and slight enough to trick the Danish site surveyors.

The Dickson Fjord event is rare but not unprecedented. Shockwaves rumbled for 18 days after the titanic, 9.1 magnitude Sumatra-Andaman earthquake and tsunami in December 2004. And consensus suggests that after the Chicxulub asteroid annihilated the dinosaurs 66 million years ago, it shook the earth for months.

At the top of his reach, Mark Hudon can only just touch Jordan Cannon’s head.

It’s an odd first impression about Free as Can Be, the Arc’teryx chronicle of the unlikely climbing duo, but it definitely hits. Does it owe to their matching outfits which, intentional or not, immediately paint Hudon as Cannon’s mini-me?

Is it Cannon’s skinny, sneaky height or Hudon’s yawning wingspan?

If the quirky Hudon is some kind of odd doppleganger for the polite Cannon, neither one seems to mind the arrangement.

“Jordan [targeted] Mark. It’s very sad, actually,” climber and filmmaker Cedar Wright jokes. “He’s preying on a senior citizen so that he can go and send his projects.”

Wright’s take is characteristically needling and clever.

Free as Can Be weaves several storylines together around one core thread, which is the year Cannon spent supporting Hudon on his goal to free climb El Capitan.

63-year-old vs 20-something

The novelty is clear but limited in a story about a friendship between a 63-year-old and a 20-something. Which makes it a good thing the film’s directorial choices are sometimes circuitous.

Hudon’s own story as a talented but uncelebrated 1970s Yosemite pioneer is vibrant and informative.

So are the interviews, especially one with Brad Gobright — which lands eerily in the 2021 film after his 2019 death.

And while the dynamics between Hudon and Cannon aren’t necessarily fresh, they do offer interesting qualities. How would Cannon, a young technician, support this transient, enigmatic elder in his challenge quest? By surprising him with a travel-oriented training program packed with modern techniques and aspirational objectives.

It builds to become a slow-burning endearment. If the odd couple setup didn’t stimulate me, the camera’s ability to capture the evident adoration between the two did.

Cannon can be serious to the point of insufferable. And while Hudon’s default mode is impish, he doesn’t always play the funny man between the two.

“Today, we’re teaching an old dog new tricks,” Cannon says in voiceover, shooting a cell phone video of Hudon racking up.

“Me being the old dog,” Hudon retorts skeptically.

“You only look old,” Cannon fires back.

Hudon’s face — half “good one, wise guy,” half “wanna fight?” — is priceless.

Overall, Free as Can Be’s colors pop. It would be easy for the film to posture at wisdom while limiting itself by sentimentality. Instead, skillful storytelling allows it to mimic the skill of its protagonists: it catches lightning in a bottle.

In a situation that humanitarians call a “disaster in the making,” loggers are encroaching on an uncontacted tribe in the Peruvian Amazon.

Survival International, a nonprofit that advocates for indigenous people worldwide, recently showed a video of several dozen Mashco Piro people on a riverbank. They are just several kilometers away from a prospective logging site. According to the nonprofit, the footage depicts a dangerous incursion. If the loggers and the natives cross paths, violence or disease could break out.

The last time the two groups clashed in 2022, tribespeople attacked workers with two-meter-long arrows, killing a 21-year-old and injuring his 54-year-old companion.

In the Survival International statement, Alfredo Vargas Pio, President of the local indigenous organization Fenamad, blamed the Peruvian government for putting the tribe in jeopardy.

“This is irrefutable evidence that many Mashco Piro live in this area, which the government has not only failed to protect but actually sold off to logging companies. The logging workers could bring in new diseases which would wipe out the Mashco Piro, and there’s also a risk of violence on either side, so it’s very important that the territorial rights of the Mashco Piro are recognized and protected in law,” Pio said.

Disputed territory

Since uncontacted tribes avoid interaction with outsiders by definition, understanding where they do and don't live can be difficult. Legally, the Mashco Piro’s land exists as a reserve right next to a 50,000-hectare logging concession owned by Canales Tahuamanu, or Catahua.

The Peruvian government granted the rights to both tracts in 2002. But it almost immediately became clear that the isolated group ranged well beyond the reserve’s borders.

In 2016, a panel from the ministry that handles Peru’s indigenous affairs found that the Mashco Piro were using land on 14 separate concessions. The panel recommended expanding the reserve and paying the difference to the affected businesses. However, the measure died on its way through the government.

Meanwhile, the situation in the Amazon began to worsen. Amid the employee slayings in 2022, Catahua sued locals advocating for the Mashco Piro in one village. A year later, a U.N. envoy asked the company to halt logging in the area, also alleging possible "forced contact” with the Mashco Piro.

In a Washington Post interview, the lawyer representing Catahua denied its workers had ever contacted the tribe.

History (and future?) of violence

This is the next chapter in a narrative of harassment that has plagued the Mashco Piro’s relationship with outsiders for over a century.

Rubber tycoon Carlos Fermin Fitzcarrald commanded a private army to slaughter most of the tribe in 1894. The episode forced the survivors deeper into the Amazon and opened a cultural wound that would not heal.

Survival’s recent images show over 50 Mashco Piro people near Monte Salvado, a village inhabited by their close cousins, the Yine, in southeast Peru. Seventeen more later appeared near a neighboring village.

It’s a stone’s throw away from Catahua’s next logging target, according to Survival. And the less-confrontational Yine previously told the nonprofit that the Mashco Piro “angrily denounced” loggers’ incursion on their land.

For companies like Catahua, regulations enforce sustainable practices — in theory. In one 2014 study, a team of international lawyers found evidence that regulatory documents actually open the door for rampant illegal logging. Among the 609 concessions active at the time, the group suspected “major violations” on 68% of them, even under the supervision of authorities.

International support for indigenous people’s land rights is widespread. The U.N. Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, International Labour Organization, and the Inter-American Human Rights Commission all recognize the rights of indigenous people on their traditional lands. And U.N. guidelines on uncontacted peoples restrict outsiders from forcing contact upon them.

As Catahua poises to open operations at the new site, the threat of more violence looms.

“The Mashco Piro are desperate. Those arrows are the proof,” Julio Cusurichi, an Indigenous leader Amazon icon, told the Post. “They would not have acted that way unless they were forced to.”

When a medium-sized cetacean resembling a dolphin washed up on a New Zealand beach, marine biologists took notice.

The whale measured about five meters long, including a beak-shaped nose, when it washed ashore on July 4. Almost no one had ever seen anything like the male specimen before, and researchers are now toiling to identify it.

The relatively unscathed remains could belong to a spade-toothed whale, according to the New Zealand Department of Conservation (DOC). If that’s what the animal is, it’s by far the world’s rarest whale.

Anton van Helden, the science advisor of the DOC’s marine species team, was on site. “There is no doubt that [a spade-toothed whale] is what it is,” van Helden said.

Spade-toothed whales are one of the most poorly-known large mammals. Since the 1800s, the DOC's Gabe Davies explained, only six samples have ever been documented worldwide. "This is huge,” he said.

The six samples include a jawbone with two teeth retrieved east of New Zealand, which first identified the species in 1874. After that, two skeletal remains showed up in Chile. Two further specimens stranded on islands near New Zealand gave clues about their color patterns, but they proved too rotten to dissect. No reports of live sightings exist.

Blubber on the rocks

Coastal marine ranger Jim Fyfe first called in the find to the DOC, sending pictures in an effort to identify it. And when van Helden caught wind of the story, he rushed to the scene.

Locals and authorities acted quickly to preserve the carcass. They first buried it in sand to prevent rot, then transported it to a freezer.

“It looked like a massive giant dolphin, the shape of it,” van Helden told The Guardian.

Identifying a 'taoka'

With its remains now safely frozen, the DOC will work to confirm van Helden’s conviction that it is indeed a spade-toothed whale. When Fyfe inspected it, he checked for its distinctive teeth — named after the flensing blades once used by whalers to remove blubber. But they were broken off and rendered no proof, The Guardian said.

The DOC has already sent tissue samples to the University of Auckland’s Cetacean Tissue Archive for DNA sequencing. The institute boasts the second-largest collection of whale, dolphin, and porpoise tissue in the world. However, DNA tests could take months.

Authorities share a special interest in the project with 8,000 registered Maori people of the Te Rūnanga ō Ōtākou tribal council. It’s the first opportunity to dissect a possible spade-toothed whale, which the council interprets as a taoka — a treasure.

The council has urged temperance.

“It is important to ensure appropriate respect for this taoka is shown through the shared journey of learning, applying mātauraka Māori as we discover more about this rare species,” Te Rūnanga ō Ōtakou chair Nadia Wesley-Smith said.

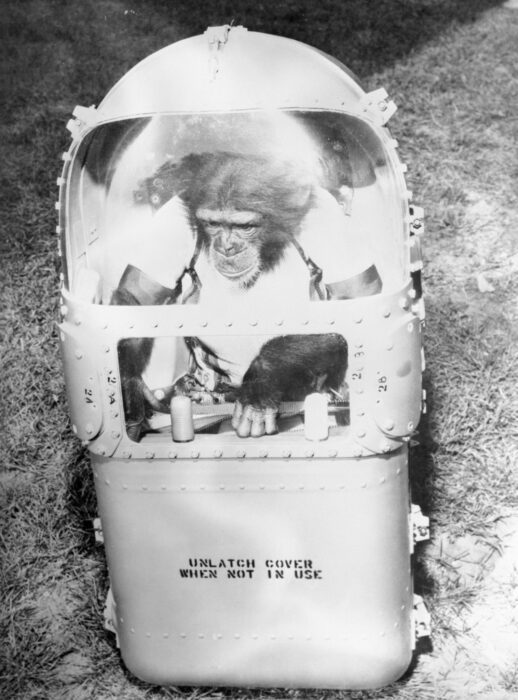

The original Mercury space capsule had no window, a hatch with 70 bolts that had to be removed from outside, and zilch for the astronaut to do except endure g-forces, hope nothing went wrong, and throw an “abort” switch on command from mission control if it did.

It was so easy a monkey could do it.

The year was 1960. Two years earlier, seven test pilots known as the “Mercury Seven” had fought through almost two years of experimental training to become the first American in space.

It is understandable if their egos were hurt when NASA decided to send up a monkey first.

Correction: a chimpanzee.

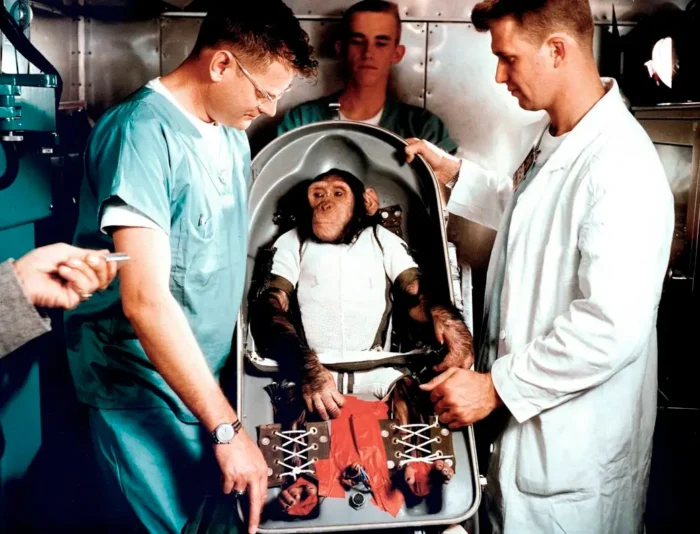

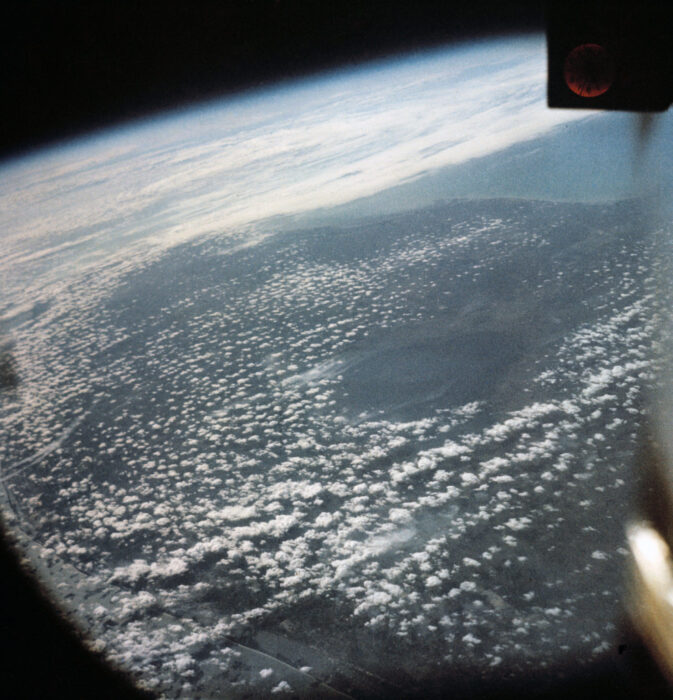

In an event that’s varyingly heralded and maligned, the first hominid in space completed his record-setting flight on Jan. 31, 1961. Ham the Astrochimp blasted off on top of a Mercury-Redstone rocket — a rig that amounted to a chair strapped to an eight-story-tall ballistic missile — and punched a hole through the atmosphere.

Ham survived a 250-kilometer-high Mach 7 flight that spiraled out of its planned path and almost killed him. At three-and-a-half years old, he became an incidental hero while still technically an infant.

Three months later, astronaut Alan Shepard became the first U.S. astronaut in space. NASA largely assuaged his and his cohort’s complaints in the years to come. All seven Mercury astronauts made landmark flights as the American space program decisively eclipsed the rival Soviets’.

Ham, meanwhile, never flew again. In fact, according to virtually all accounts, he refused to.

Though the ape was “grinning” when recovery crews rescued him from a sinking Mercury capsule and brought him aboard the U.S.S. Donner, all may not have been well. When handlers later brought him near the “couch” he sat in for his 16.5 minutes in space, he recoiled from it.

In 1983, Ham died from liver failure at a North Carolina zoo at around 26 years old. The Astrochimp’s remains now lie in a commemorative grave at the International Space Hall of Fame in Alamogordo, New Mexico.

But what good is a Hall of Fame honor to a chimp?

It’s been 60 years since NASA closed the books on Project Mercury. Now, space historians, animal advocates, and even philosophers have all spun Ham’s story into a complex fabric that unites humans with our closest living ancestors — but also highlights a mutual isolation.

Number 65

Ham was born in approximately 1957 in what was then French Cameroon, West Africa. Captured by trappers, he soon ended up at a Florida tourist attraction called the Miami Rare Bird Farm. In 1959, the U.S. Air Force purchased the young chimp for $457 and transferred him to Holloman Air Force Base in New Mexico.

The facility spelled out Ham’s name in acronym — Holloman Aerospace Medical Center — but at first, he was just a number.

The U.S. military had been busy acquiring chimps to support testing for the space program. Urgency had run high since October 4, 1957, when the U.S.S.R. struck fear into the free world by launching a microwave-sized, largely inert object.

Sputnik 1 had achieved an elliptical low-Earth orbit, which it proved by transmitting basic, beeping radio signals around the planet.

It’s hard to overstate the primitivity of early space engineering. At the start of the Mercury program, engineers were still trying to figure out if humans could perform tasks in orbital flight as mundane as operating levers. It’s one of the factors that make those early achievements so astonishing.

Enter Number 65 and the rest of Project Mercury’s test chimpanzees.

When NASA personnel selected him and 39 other chimps for aptitude testing — which was virtually identical to the human astronauts’ training — the only living creature in space had been Laika, the Soviet dog.

Laika, a stray plucked from the Moscow streets, died in orbit on a 1957 mission that became infamous for animal rights abuse even at the time. In a cruel turn of early space travel, Sputnik engineers shot the female stray into space with one meal and the expectation that she would run out of oxygen and die in seven days. (The flight went awry and she likely died within hours.)

NASA officials claimed that the U.S., in contrast, chose chimpanzee pilots because they wanted the animals to survive their flights from liftoff to capsule recovery and work while they were on board.

They resembled astronauts, could potentially perform similar tasks in the capsule, and were docile, NASA said.

NASA manuals referenced in the 1998 book, This New Ocean: A History of Project Mercury, read:

Intelligent and normally docile, the chimpanzee is a primate of sufficient size and sapience to provide a reasonable facsimile of human behavior. Its average response time to a given physical stimulus is .7 of a second, compared with man's average .5 second. Having the same organ placement and internal suspension as man, plus a long medical research background, the chimpanzee chosen to ride the Redstone and perform a lever-pulling chore throughout the mission should not only test out the life-support systems but prove that levers could be pulled during launch, weightlessness, and reentry.

Flight school

Ham the Astrochimp’s training followed B.F. Skinner’s conditioning theory: rewards for the correct response, corporal punishment for the wrong one.

Project Mercury handlers strapped chimps into simple chairs, facing a panel fitted with colored lights and levers. According to the National Air and Space Museum, they earned banana pellets if they responded to the right light-and-sound cue by activating the right lever. If not, they received electrical shocks on the soles of their feet.

They endured rocket sled launches, sat in isolation training, and performed intelligence tests. They also underwent g-force testing in a massive centrifuge at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, just like the astronauts. Incessant medical checkups and monitoring accompanied the regimen.

Edward C. Dittmer, Sr., a World War II veteran and non-commissioned laboratory officer, acted as Ham’s lead trainer at Holloman. Later, he repeatedly praised the chimp’s trainability and sometimes humanized him.

Dittmer said, according to the Space Hall of Fame:

“...I think…I know he liked me. I’d hold him, and he was just like a little kid. He’d put his arm around me and he’d play, you know. He was a well-tempered chimp.”

Tom Wolfe, author of the celebrated Mercury Project chronicle The Right Stuff, wrote that the relative peace was hard-won. Before “rebellion proved to be a dead end” for the chimps, he wrote:

The beasts tried everything they could think of to escape. They snapped, snarled, bit, thrashed at the straps, and made runs for it. Or they bided their time and used their heads. They would go along with a training task, seeming to cooperate, until the white smoker seemed to let his guard down — then they’d make a break for it. But the resistance and the wiles were of no avail. All they got for their struggles was more zaps.

Engineers at Holloman culled the entry class of 40 primates down to 18. Six finalists, including Ham, moved on to Cape Canaveral, Florida for final testing.

Starting on January 2, 1961, 29 separate tests stood between the chimps and the planned suborbital flight. Three weeks later, NASA wrote, the tests “had made each of the six chimps a bored but well-fed expert at the job of lever-pulling.”

When the electrical shocks and the banana pellets abated, Ham emerged at the top of the pile along with a female alternate.

“The competition was fierce, but one of the males was exceptionally frisky and in

good humor” in the days leading up to the space flight, NASA wrote.

Ham and his alternate went on a “low-residue” diet 19 hours before liftoff and awaited circumstances they couldn’t possibly anticipate.

Rocket rides

Until flight day, Jan. 31, 1961, the United States space program had produced discouraging results.

Throughout the '50s, Jupiter and Atlas rockets veered off course and exploded spectacularly, on and off the tortured Cape Canaveral launchpad.

The Redstone proved more reliable in early tests but was still a beast of a machine.

It was essentially a 10-meter aluminum can of liquid oxygen and ethyl alcohol on top of a gaudy combustion engine. First designed as a surface-to-surface ballistic missile with an 800km range, it generated 35,380kg of thrust and tore through the sky at 9,400 kph, or Mach 7.5.

The Mercury capsule acted as its nosecone, and the astronaut — or astrochimp — held on for the ride.

The first Mercury-Redstone launch attempt, MR-1, took place on Nov. 21, 1960 — just over two months before Ham’s flight. It was an unmanned test, and despite the rocket’s menacing power, anyone or anything strapped into the capsule that day would have experienced almost nothing but a meek trip from the top of the rocket back to the ground.

When NASA hit the ignition on MR-1, the rig fumed briefly, climbed a few centimeters off the launch pad, and settled back down. Then, comically, an electrical chain reaction caused the escape tower to blast off and deployed the still-attached capsule’s drogue (or safety) parachute.

The so-called “four-inch flight” drew public ridicule to Project Mercury, along with a little levity. But it also introduced glaring safety concerns. If Ham or any astronaut had been on board, they would have been trapped on top of a teetering, 25-meter-tall live bomb.

The failure also delayed planned tests of the recovery system. This was a critical piece of the Mercury program, in part because capsules would touch down in the ocean off the Florida coast. Recovering a capsule was an all-hands-on-deck situation: a plethora of aircraft and ships were involved. Failure meant the capsule could sink, dooming its occupant to drown.

By the time Ham and his alternate astrochimp made their final trip out to the launch pad for MR-2, only one Mercury-Redstone test (MR-1A) had succeeded.

Malfunctions and setbacks delayed Ham’s January 31 flight almost to the breaking point. And when the rocket finally did lift off, it put him through conditions more extreme than anyone expected.

‘Ham’ in a can

Accounts report Ham’s condition as calm on the morning of the launch. His handlers secured him in his couch, then trolleyed him toward the Redstone.

This New Ocean renders the moment stirringly, if oddly:

“There, an hour and a half before the scheduled launch time, the chimpanzee named ‘Ham,’ still active and spirited although encased in his biopack, boarded the elevator to meet his destiny.”

MR-2 was scheduled for liftoff before noon because mission control didn’t want to risk a night recovery. According to NASA, the hours-long countdown and final check process went as planned until about 7:45 am. That’s when a “tiny but important” inverter in the automatic control system started overheating.

Nevertheless, technicians loaded Ham into the capsule at 7:53 am and bolted down the heavy hatch for liftoff.

Hours of delays followed as mission control tried to fix the inverter. Chaos beset the launchpad, too, as an elevator got stuck, too many people took too long to clear the pad area, checks of the environmental control system ran 20 minutes too long, and flaps on the rocket’s booster tail jammed.

At 11:40, This New Ocean’s authors wrote, “it was decided that now or never was the time to go today.”

Five minutes before noon, controllers hit the red button, and Ham shot skyward.

Seconds into the flight, the Mercury-Redstone started to pitch upward. A launch angle just one degree steeper could significantly alter the flight plan. Speed, duration, recovery point, and g-forces all changed dramatically.

According to NASA, the high angle slammed Ham with a maximum g-force of 14.7 (making his body weigh 243 kg). He experienced 58,000kg of thrust for one unplanned second, and his 8,200 kph top speed was about 1,000 kph faster than planned.

Ham’s flight hit its apex at 253km — about 150km above the rough threshold between Earth and space. He was weightless for 6.6 minutes, according to NASA, during a flight that lasted two minutes longer than expected.

At the capsule’s highest point, NASA knew Ham was going to come down farther away — much farther away — than mission control hoped.

“At its zenith, Ham's spacecraft was already 77km farther downrange than programmed,” NASA calculated. He landed over 200km away from his target landing site.

Ham still wasn’t out of the woods. Cabin pressure had plummeted at one point during the flight. NASA later traced the problem to a spring-loaded valve that had unexpectedly popped open from vibrations.

This breech, and a rough landing due to an overcooked reentry, almost spelled the end for Ham.

When the capsule splashed down at 12:12 pm, it turned upside down and started sinking. The closest rescue was a destroyer stationed almost 100km away.

When the helicopters arrived on the scene, they found the spacecraft on its side, taking on water, and submerging. Wave action after impact had apparently punished the capsule and its occupant severely. The beryllium heatshield upon impact had skipped on the water and bounced against the capsule bottom, punching two holes in the titanium pressure bulkhead. After the craft capsized, the open cabin pressure relief valve let still more sea water enter the capsule.

Pilots finally recovered the spacecraft around 3 pm, filled with about 360kg of water.

It’s unknown how long it would have taken the capsule to sink, but Gus Grissom almost drowned under similar circumstances on MR-4 six months later. (NASA incorporated an explosive escape hatch into the Mercury design in the interim.)

Through his ordeal, Ham reportedly remained calm and performed admirably — pulling his levers when prompted to avoid the shocks on the soles of his feet. The punishment program was strenuous, with a clock that reset to schedule a new shock every 15 seconds. If Ham failed to prevent it, he would get a full blast.

(Enos, who became the first chimpanzee to orbit the Earth later that year, endured an especially grim situation. During his three-hour flight, the shock system shorted out and inverted. The five-year-old chimp responded to every prompt perfectly but still received 76 shocks.)

Grounded

Ham never flew again. Despite the “grin” he displayed as he accepted an apple after MR-2, he refused to go near his couch for a photo shoot on a later occasion. Though interpreted as a happy gesture at the time, the grin likely meant something else.

The world-famous Jane Goodall assessed it for the 2003 film One Small Step: The Story of the ‘Space Chimps.’

“Actually, that is the most extreme fear that I’ve ever seen on any chimpanzee,” she said. It’s now widely thought that when a chimpanzee shows its top teeth during a smile, as Ham did, it’s not a smile — it’s a “fear grimace.”

From the deck of the U.S.S. Donner in 1961, Ham’s story didn’t get brighter. NASA eventually transferred him to the Smithsonian Zoo in Washington, D.C., where he lived alone until 1980. (It’s also widely understood that chimpanzees need companionship to flourish.)

Finally, Ham arrived at the North Carolina Zoological Park in a habitat among several other chimps but died of liver failure three years later. NASA would macerate his corpse for research: separate the flesh from the bones, usually by soaking in room-temperature water. His skeleton showed no signs of stress from his space flight, according to the U.S. National Museum of Health and Medicine. His soft tissue was cremated and transported to his ceremonial grave at the Space Hall of Fame.

It’s impossible to quantify the stimulation Ham incurred during his Project Mercury experience — or during the rest of his life. Shock treatment on monkeys started PETA, and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has repeatedly tried to ban it on humans. The human body can only endure the g-forces Ham survived for about a minute.

“Being unable to debrief his handlers, Ham alone knew at this time how grueling his flight had been,” said Robert F. Wallace, an information officer onboard the U.S.S. Donner when Ham landed.

There’s an aviator slang phrase for a pilot with no control over his ship. To a pilot, “SPAM in a can” means exactly what it sounds like: your aircraft is the can, and you’re the SPAM.

Ham’s name is an acronym, sure, but how hard is it to make the SPAM leap?

“[Ham] still would have been nursing at age 3 ½, dependent on his mother for survival,” Save the Chimps points out. “It is hard to imagine a human toddler performing as well as Ham in this challenging task. It speaks to his character, intelligence, and bravery.”

Ham’s involuntary contribution helped re-orient the space race in favor of the U.S., which NASA acknowledged. But if his Project Mercury cohort visited him after he left the program, no record of it exists.

“Ham's survival, despite a host of harrowing mischances over which he had no control, raised the confidence of the astronauts and the capsule engineers alike,” This New Ocean reads.

Wolfe puts a considerably sharper point on it in his last mention of Ham in The Right Stuff. The public attitude toward human space flight after Ham’s success, he wrote, boiled down to “‘My God, do you mean there are men brave enough to try what the ape has just gone through?'"

In a crowded field of climbing films that are increasingly hard to tell apart, Mike Call’s The Artist kept me guessing. My notes are tangled and scrawled, and (perhaps largely due to personal reasons) would be stained with saline if I’d been leaning over the paper instead of backward.

Can you expect the son of this woman to portray a mundane hero?

Let me explain what I mean by “kept me guessing.”

Here’s a linear story arc The Artist could follow:

Boone Speed anchored sport climbing in the 1990s, burning a trail through American Fork Canyon that fried everyone not named Chris Sharma. Then he played an instrumental role in inventing modern bouldering gear and creating the market for it. Then he became a world-class photographer.

All along, his unforgiving personality burned just as hot as his ambition. He ostracized some of his closest friends. Everything he did “put a dent in the world,” in Call’s words, but he appeared to pay the price for it. It looked like he couldn’t break through whatever membrane was keeping him restless in his own skin.

Then later in life, he cooled off — realizing, as he says in the film, that his oldest relationships are the most important thing. He sums up the epiphany with a familiar sentiment: “How much better does it get?”

All of that’s true. But, like all art, there’s what The Artist appears to do, and then there’s what it actually does.

Here’s what it actually does:

Describes Speed’s early dynamism from behind the lens

Call was Speed’s earliest videographer. Three decades later, their relationship is the same. But instead of depicting a one-dimensional Speed by handing him the narrative reins, Call tells it his way — which adds depth to his subject right away.

Emphasizes real-world outcomes

Introducing key mentors like Maria Cranor, Black Diamond’s marketing director while Speed was embroiled in generating the modern bouldering market, provides accountability. Cranor and other key influences create rules and boundaries for young Speed, shaping his decisions.

Pusher, a company that Speed helped found, wasn't just a collective of heathens. It was the first climbing company that paid no attention to anything except bouldering. Pusher sold an aesthetic involving T-shirts, ads, and some seminal videos. It also made climbing holds.

Allows its aesthetics to penetrate

The Artist exalts the aesthetic principle of reduction: Do more with less. You can see it in Speed’s interior decoration, with demure houseplants and a small reproduction of one of his father’s sculptures. It’s also the principle he applies to guide his photography.

And if you’ve ever climbed, you know how to apply it.

The film stays out of the way, allowing emotive expression from images, colors, and interview subjects alike.

Pumps the gas — but doesn’t over-rev

Speaking of Speed’s father, don’t miss the son describing how he felt after his father died. But don’t expect lingering close-ups of misty eyes or quivering lips. Call knows the viewer can feel every bit of the moment’s pathos without having their head dunked in a bucket of it.

(For the record, yes, this is the part that got me choked me up.)

Elsewhere, skip to 14:10 for peak tough-guy Boone.

Focuses on the art, not the artist

So The Artist doesn’t focus on the artist?

Correct, it does not. Instead, it watches what the artist is watching: his subjects. In a way, Speed is the hero of the film. But not really. Because it’s actually about everyone except him.

In the fat part of the bell curve of climbing films, production crews can labor in dramatics, saturated visuals, or tired storylines.

Another segment in the big part of the curve is the predictable. We watch a climber trace a typical heroic cycle of accepting challenge, faltering, transforming, and eventually meeting the challenge to achieve redemption.

The Artist pretends to be both; instead, it’s neither.

There's more to explore that way.

In 1250 AD, a cluster of earthen mounds by the Mississippi River swarming with artisans, farmers, and even astronomers was the place to be. It was known as Cahokia.

By 1350, it was a ghost town.

Why?

Located across the Mississippi River east of modern-day St. Louis, Cahokia was in its day the largest North American city above Mexico. Its 20,000 souls belonged to a group of Algonquian-speaking tribes from across the lower Midwest. They survived by farming.

Generations of archaeologists have carved away at the soil in the U.S. state of Illinois to find out what happened in those hundred years to cause the thriving town's demise. Researchers have now discarded one of the most popular theories, that severe drought caused crop failure. Prairie grasses, the theory went, then moved in during the drought, replacing crops like maize and squash with inedible roughage.

The tidy hypothesis followed other tales of civilizational extinction. But according to the U.S. Bureau of Land Management (BLM) and Washington University in St. Louis, it didn’t happen.

"Given the diversity of their known food-base, the domesticated landscape around Cahokia may have been resilient in the face of climate change and capable of producing more food than was required by Cahokians," the researchers wrote in a paper published last month.

Scratch the most popular theory of their mysterious disappearance.

View this post on Instagram

No catastrophes

Soil samples extracted from deep underground reveal that no catastrophic crop failure occurred. The study’s co-authors counted carbon isotopes in the soil from throughout the Cahokian period. If particular isotopes kept showing up in layer after layer of soil, they would paint a picture of consistent soil composition over time. In turn, this would indicate whether drastic changes in cultivation had taken place.

The study revealed a consistent presence of Carbon-12 and Carbon-13 across samples. No major death of one dominant plant species — or growth of another — had occurred.

"We saw no evidence that prairie grasses were taking over," said archaeologist Natalie Mueller, who led the study.

However, that doesn’t mean a drought didn’t happen — it just means the Cahokians may not have perished under its pressure.

Co-author Caitlin Rankin of the Nevada Bureau of Land Management said the Cahokians were good enough engineers to keep crops irrigated through dry cycles. They were such skilled builders that Monks Mound, an iconic prehistoric earthwork, is the largest pyramid north of Mesoamerica.

So why did the Cahokians abandon their proud city? One separate theory, also using soil cores, focuses on flooding along the ancient Mississippi.

Rankin and Muelle aren’t sure yet. For now, they suggest that the abandonment happened slowly.

A Spanish tourist is dead in a South African wildlife refuge after what one outlet called a “horrific” trampling.

Reports say the 43-year-old man was riding in a vehicle with his fiancee in Pilanesberg National Park on July 7. The group encountered a herd of elephants, including several calves, near the park gate, about 180 kilometers northwest of Johannesburg.

Ignoring park policy and warnings from his fellow passengers, the man dismounted from the vehicle and approached the herd on foot, camera in hand.

When one adult elephant charged the encroaching tourist, he fled. Soon, others in the herd followed. The group caught the man and trampled him to death in a 30-second incident that left, witnesses told the Daily Mail, nothing but “the tattered blood-soaked clothing of the tourist and the remnants of the tourist's body crushed into the earth.”

Camera's have a zoom function for a reason...

Safari in Africa is one of those reasons!Spanish tourist trampled to death by elephants in South Africa https://t.co/jE5l1iX7ZR #groundnews via @Ground_app

— Alex Robson (@AlexI_IRobson) July 9, 2024

No further aggression

Once the elephants finished attacking the man, they reportedly retreated into the bush with no further aggression toward the other individuals and vehicles present.

Rangers responding to the scene could not help the trampled victim. Some witnesses attributed the incident to the elephants’ protective instincts over their calves.

Park officials handed the case to police for further investigation. Tourists in Pilanesberg are welcome to drive their own vehicles, and most of the park is accessible in a typical commuter car. However, Piet Nel, the North West Parks and Tourism Board's acting chief conservation officer, told ABC News that strict rules against leaving vehicles apply inside the park.

Pilanesberg park officials inform visitors they're not allowed to leave vehicles, Nel said — and that each visitor signs a form showing they understand the rule. A police spokesperson told the Daily Mail that Sunday's victim was driving the car he was in, stopped, and got out on his own.

“In some cases, people are oblivious to the dangers in the parks,” Nel said. "We must remember that you are entering a wild area. The [Parks and Tourism] Board is very saddened by this tragic accident and would like to express their sincere condolences to the deceased's next of kin and friends.”

Officials have released no further details about the victim. Sun City, a famed resort and casino that borders the park, reportedly sent professionals to aid the dead man’s traumatized companions.

The fatality marks this year’s third deadly elephant attack on a tourist after two Americans died in separate incidents in Zambia.

In the wide world of whale sex, the largest of all species also ranks among the most private.

The intimate lives of the planet’s biggest animals range from eye-opening to relatable to hilarious. But of all cetacean species, we may know the least about the reproductive habits of blue whales.

At least now, we know where to look.

Marine biologists in Timor-Leste, a modest island situated along a major blue whale migration route between Australia and Indonesia, submitted the first underwater footage of a mother blue whale nursing a calf. The two animals are actually pygmy blue whales — a subgroup that’s several meters shorter than the species’ biggest individuals.

The Timor-Leste discovery, part of a 10-year study, could signal more groundbreaking insights to come.

“Our decade-long project has documented some of the lesser-known intimate reproductive behaviors of blue whales, some for the very first time,” said Karen Edyvane, marine ecologist and project lead on the Australian National University study. “From newborn calves and nursing mothers to amorous adults in courtship, the waters of Timor-Leste really are providing blue whale scientists with some of our first glimpses into the private lives of one of the world’s largest but most elusive animals.”

Like their parents, blue whale calves are enormous. Newborns average seven meters long and weigh in at 2,300-2,700 kilograms. They also grow rapidly, thanks in part to their mothers’ generous supply of high-fat milk. A new blue whale mother can produce 50 gallons of her 35-50% milk-fat lactate each day, according to the Marine Mammal Center. When a calf nurses healthily, it can gain an incredible 4.5 kg each hour.

None of that has helped scientists observe this or any other blue whale reproductive behavior, though. In 2018, scientists off the coast of Sri Lanka tracked two individuals performing a mating ritual for several days. The huge animals spend so much time feeding on krill, National Geographic explained, that “seeing other behaviors is quite rare.”

The ongoing effort to better understand these iconic, endangered whales could focus on Timor-Leste. Its deep coastal waters host famously prolific blue whale migrations each season along a 5,000km migration route. Whale tourism is popular on the island, and researchers identified it as one of the “most accessible and best” blue whale research locations.

As such, participatory citizen science fueled the success of Edyvane’s team. Research partner Jose Quintas, National Director for Environment and Research at the Timor-Leste Ministry of Tourism, said tourists, students, and anglers all shared information that drove the project forward.

As the project concludes, Quintas emphasized conservation as a key objective in the ongoing regional mission. The World Wildlife Fund estimates blue whale numbers at 10,000-25,000 — down from a pre-whaling population of 250,000 or more.

“We really need to use this valuable new information to ensure we fully protect and conserve these animals when they pass through Timor-Leste’s waters and beyond,” Quintas said. “For this, we urgently need cooperation and support from Australia and the wider international community.”

For the species to keep rebounding, it’s pivotal for young whales like the pygmy blue in the video to survive. Blue whales are thought to reproduce slowly — about once every two to three years.

When embattled deep-sea tourism startup OceanGate lost its only submersible and its CEO in one catastrophic dive last June, reactions varied.

Most of the world watched with bated breath as emergency crews tried to locate the lost ship and rescue its five-person crew. Media focus ranged from tragic and personal to skeptical — repeated safety issues and setbacks had plagued the Titan throughout its development. Stockton Rush, OceanGate’s CEO and the submersible’s pilot, had made charged comments about regulations and safety in the deep-sea exploration industry.

To state it gently, the Titan was an outlier in design. The pilot’s interface was a video game controller. The only interior fixtures were two screens and a front porthole window. And the crew squatted on the floor for the duration of each voyage, seated on a plain rubber mat.

Not to mention its carbon fiber hull — a first-of-its-kind gambit that, now, will likely never again be attempted.

The search for the Titan and its crew ended when remotely operated vehicles found it in pieces on the ocean floor. The U.S. Coast Guard called the incident a “catastrophic loss” of pressure inside the cabin. Official investigations commenced, and OceanGate promptly shuttered operations.

James Cameron speaks out

Some experts, including experienced deep-sea submersible pilot and film director James Cameron, later implied Rush had been on a dangerous crash course all along.

“You don’t move fast and break things if the thing you’re going to break has got you inside it,” the director recently told 60 Minutes Australia.

As the Coast Guard and other agencies continue their investigations, tech news outlet Wired recently shared the results of its own year-long probe involving “tens of thousands” of OceanGate documents and internal communications.

Dating back to the company’s early days in 2013, the investigation plots a chronicle of compounding decisions by Rush and other key individuals leading up to the Titan disaster.

This timeline navigates the tortuous development of the doomed submersible.

2009

OceanGate opens with plans to charter deep-sea trips for tourism and research. It first uses older, steel-hulled craft.

2013

CEO Stockton Rush announces plans for a new carbon-fiber submersible. The lightweight material makes a cylindrical build feasible, according to Rush, adding more capacity for passengers than traditional sphere-shaped designs.

2015

OceanGate first tests the concept with a steel prototype called the Cyclops 1. Red flags pop up right away. Reporting for New Scientist, investigative reporter Mark Harris dives with Rush in an early test. He reports the Cyclops glitches badly at only 130 meters.

'Scared the shit out of everyone'

2016

Designs continue to fluctuate and fail across multiple experiments with different materials for critical components. Wired later reveals OceanGate’s testing protocols clash with engineers’ recommendations.

According to Wired:

- In a pressure test at a University of Washington lab, a carbon-fiber scale model of the Cyclops 2 implodes at about 6,500 psi — close to the water pressure at 3,800 meters, the depth of the Titanic, but thousands of meters short of OceanGate’s target safety margin. “The building rocked, my ears rang for a long time,” reads an employee email. “Scared the shit out of everyone.”

- Cyclops 2 prototypes never survive the targeted safety-margin pressure in testing, and the company never tests the titanium components the final sub will use in conjunction with the fiber. Instead, the company thickens the hull specs from 4.5 to 5 inches and commissions a contractor to build the final design.

- When it arrives, it is too thick for portable ultrasonic testing equipment. Ultrasonic testing can detect miniscule flaws or weak points in the final product without destroying it. Testing would have been possible with a stationary ultrasonic rig. Instead, Rush concludes transporting and testing the Titan is too expensive. Ultrasonic tests never occur.

- Finally, the ship uses an acrylic viewport that falls far short of pressure safety targets. Will Kohnen, the designer of the nine-inch-thick unit, later tells Wired that OceanGate fell well short of a rigorous testing protocol for the unit. He claims that he only rated the window to 650 meters. When he urges Rush to reconsider the component, the CEO allegedly refuses.

'You are going to kill someone'

2018

According to Wired:

- Rush fires marine operations manager David Lochridge after Lochridge refuses to sign off on the final sub, citing 27 safety issues from flammable materials to missing bolts and more concerns over the carbon fiber hull. Lochridge files a whistleblower report to the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), but Rush sues him for breach of contract, leading Lochridge to drop the complaint.

- “Titan and its safety systems are way beyond anything currently in use…I have grown tired of industry players who try to use a safety argument to stop innovation and new entrants from entering their small existing market,” Rush wrote to McCallum in one of the Wired documents. “Since [starting] OceanGate, we have heard the baseless cries of ‘You are going to kill someone’ way too often.”

- Rob McCallum, a deep-sea explorer, also seeks to discourage Rush from proceeding in a petition drafted by Kohnen.

- One safety system relies on acoustic feedback from the carbon fiber hull as it crackles and pops under pressure. OceanGate frames it as an early-warning system that can signal the crew to surface at a certain threshold of “micro-buckling.” A safety consultant familiar with material acoustics says that the noises actually indicate “irreversible” damage to the hull.

- Real-world testing began but proceeded poorly. The submersible once nearly broke apart in shallow, choppy water with Rush inside. And when the Titan first reached 4,000 meters, the hull warped alarmingly — by up to 37% more than intended, according to engineers.

- Rush starts to worry about noises from the hull at depth. Finally, a pilot inspecting it with a flashlight notices a crack. Later, OceanGate finds 11 square feet of carbon fiber delaminated — meaning the layers of material had separated.

A successful dive

2021

According to Wired:

- Contractors re-manufacture the carbon hull using updated techniques. It passes pressure tests at a University of Maryland lab, but OceanGate elects to salvage the old titanium rings from the damaged sub based on Rush’s intolerance toward added cost and delay.

- An employee spots new lifting points attached to the two titanium rings. They’re a new addition, and a representative from the original manufacturer had warned OceanGate back in 2017 to raise and lower the vehicle only with nylon slings: “The titanium cannot take load/tension,” the individual said.

- July 13 - OceanGate completes its first successful visit to the Titanic with tourists.

2022-23

But problems persist, from inane to frightening. OceanGate cancels a 2022 mission with Intelligencer reporter David Pogue on board when, 11 meters below the surface, two rubber floats come partly untethered from the sub’s launching platform.

View this post on Instagram

'MacGyvered'

The event comes a year after a crew gets trapped on board the Titan. Instead of the programmed six hours, the expedition lasts 27, much closer to the cabin’s 96-hour oxygen threshold.

Inspecting the vehicle before his failed outing, Pogue tells Rush that the sub feels “MacGyvered.” When Rush acknowledges the comment, Pogue asks if that has concerned anyone else in the deep-sea industry.

Rush tells Pogue:

Oh yeah! Oh yeah. Yeah, no, I’m definitely an outlier. There’s been more intrigue into that than I can go into. There were a lot of rules out there that didn’t make engineering sense to me. They made sense at the time, in the ’60s and ’70s. But, you know, there’s a limit. You know, at some point, safety just is pure waste. I mean, if you just want to be safe, don’t get out of bed, don’t get in your car, don’t do anything. At some point, you’re gonna take some risk, and it really is a risk-reward question. I said, “I think I can do this just as safely by breaking the rules.”

June 18, 2023 - Titan dives toward its famous target but never returns. The U.S. Navy eventually reveals it detected “an acoustic anomaly consistent with an implosion” shortly after the Titan’s surface crew lost contact with it, according to CBS.

The U.S. Coast Guard launches an investigation, which continues today.

If people rock climbed before 1492, the evidence is conjectural.

Villagers inhabited the Sky Caves of Nepal, carved into stone hundreds of meters off the ground, as early as the seventh century BC. Asked how the ancients got up there, locals are known to quip, “The lamas fly.”

Similar sites exist in the western United States, where thousand-year-old groups like the Mogollon left faint traces of climbing to cliff dwellings and cultural depots such as Hueco Tanks.

But no documented record of a climb existed anywhere in the world until 1492. That year -- which coincidentally was also the year that Columbus set sail -- King Charles VIII decided to force one of his military engineers to climb Mont Aiguille — a 400m limestone mesa some called Mount Inaccessible. On its flat top, angels allegedly cavorted.

The engineer's name was Antoine de Ville. He and 10 other intrepid souls started up the northwest face armed with wooden ladders.

By all accounts, de Ville and his team did reach the 2,087m summit. After their unlikely flurry up hundreds of meters' worth of ladders, nobody else repeated it for centuries.

Most advanced ever

De Ville’s first ascent was the most advanced known rock climb relative to the rest of its era. Former American Alpine Journal editor J. Monroe Thorington’s 1965 report had this to say about the Mont Aiguille route: “The ascent was said to be ‘half a league by ladders, and a league by a route terrifying to see and even more so to descend.’ Only a few years after the event, Antoine de Ville was spoken of as an ‘alchimiste,’ a sorcerer!”

According to Thorington's research, ground witnesses sourced from French authorities corroborated that de Ville had actually summited Mont Aiguille.

De Ville simply called the ascent “le plus horrible” — “the worst.” Details on the campaign itself are scarce. But all 11 members, including multiple religious officials and a “ladder-man to the king,” seem to have topped out on Mont Aiguille.

Quick repeaters scurry up ladders

De Ville and his crew first spent a few days on the summit meadow building a mountain hut -- no details on how they carried the lumber up those ladders. They also erected a few crosses in the name of Charles VIII and wrote fantasy reports about unusual flora and fauna, and some mysterious human footprints.

The note about footprints turned out to be prescient, Thorington reported. Two more groups of local nobles and bureaucrats soon followed de Ville’s ladders to the top.

“Imagine their astonishment,” he wrote, when conspicuous people such as a viscount popped up onto the mesa.

Ladders, sorcery, or otherwise, it’s beyond argument that de Ville was ahead of his time. Later climbers retrofitted his route with fixed safety gear, including iron chains. American climber and historian W.A.B. Coolidge repeated it in 1881. His account, per Thorington:

"The way (center of NW face) lies through several deeply cut fissures, or rather, hollows of the most extraordinary nature. At one moment, we seemed to be in the very bowels of the mountain in a great cavern, whither scarcely any light penetrated. The rock is very smooth and bad to climb, so I was glad to avail myself of the iron chains.”

Today, climbing beta website The Crag calls de Ville’s route the Voie Normal and rates it at a gentle 4a (5.4).

Maybe controversially, the site credits the first ascent to Jean Liotard in 1834 — the man who allegedly arrived second, 342 years after de Ville.

Of course, most believe that de Ville genuinely summited the peak. A few have even tried to re-enact the legendary ladder ascent for a documentary project. It continues to be an intriguing objective for the historically minded.

Tomorrow’s objective: Mont Aiguille- The oldest documented rock climb in the world 1st done in 1400… pic.twitter.com/4bySgInEbp

— Mark Seaton (@guidemark) July 2, 2024

Inside their complex colonies, ants take on one of several vocations: hunter, engineer, soldier, explorer, queen — and hitchhiker?

When car owners filed reports of temporary ant infestations in their vehicles, the stories circulated on social media. In the incidents, which took place in heavily populated north and central Taiwan, thousands of ants crowded into car trunks, crevices, or even engine compartments.

Danger danger Ant-Voltage!

Returned to disconnect the car from the charger this morning & found these guys going about their business.

Removed adaptor carefully & carefully removed Ants on the floor so they all return home safely. #poletopole #nissanariya pic.twitter.com/iQDvJFkAHl

— Pole to Pole EV (@PoletoPoleEV) August 8, 2023

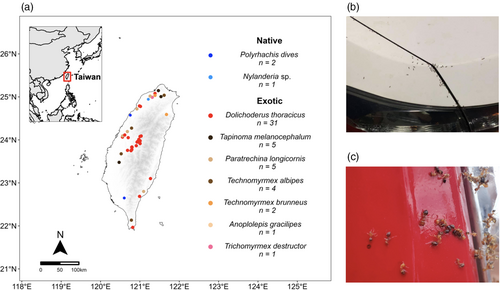

In all, researchers found nine species of largely invasive, tree-dwelling ants hitching free rides. But could they actually be migrating on purpose?

Six-legged hitchhikers

Virginia Tech entomologist Scotty Yang led a study that leveraged citizen science to investigate. According to his team, the ants are in fact looking to broaden their horizons — and their territory.

The team documented 52 cases of “ant hitchhiking” on 44 cars and eight scooters from 2017 to 2023. In each event, a car or scooter owner spotted a swarm of ants on their car, then joined a Facebook group Yang started and reported where they were parked, how long they had been there, and where they were going next.

While some cases looked like foraging, many related more closely to the ants’ “exploratory” behavior, the study found. Workers sometimes escorted a queen and larvae into a car that was empty of food or other attractants, presumably focused on finding a new area to colonize.

Of the nine ant species represented in the study, seven were invasive. Territorial expansion is integral to every invasive species, Yang pointed out. Ants like the black cocoa ant (Dolichoderus thoracicus), which accounted for 60% of the hitchhiking, thrive outside their own habitats because they can overwhelm competitor species in others.

“Tracking invasive insects and how they spread is an important subject for entomologists because these creatures can represent threats to native species of plants and animals,” Yang told Earth.com.

In the urban jungles from which the ants were mainly migrating, the impulse to move out makes sense. Researchers already knew ants in crowded areas often transported their colonies from trees onto building surfaces or other fixtures.

Effective, invasive, pervasive?

If the black cocoas and other ants in the study were looking for new neighborhoods, their strategy was sound. Yang’s research found they could have traveled several hundred kilometers in the infested vehicles — “largely exceeding” their natural ability to spread through dispersal.

Repurposing human infrastructure to do it also made sense. Taiwan is one of the world’s most densely populated countries, so wildlife corridors are often choked by sprawling cities. Ants in the study shared the common factors of strong climbing ability, heat tolerance, and aggressive foraging instincts.

To cling onto their arboreal homes, ants like black cocoas use hooked claws and retractable adhesive pads on their feet. Exposed to the elements, they don’t benefit from temperature-regulated underground nests like other ants. And, the study said, they’re notably vigilant. Because their canopy habitat has limited resources, they “exhibit frequent foraging activities and territorial patrolling” around their nesting trees.

Finally, every driver in a hot city loves a shady parking spot — usually right under a tree.

The authors admitted their study’s volunteer setup limited data availability. But they also suspect ant hitchhiking is far more common than they currently grasp.

Yang’s project envisions a future framework for managing the adaptive technique. The stakes could be high.

One of the world’s most successful invasive ants is also a freeloader. Yellow crazy ants (Anoplolepis gracilipes) find frequent passage on cargo ships transporting produce. Though their original habitat is disputed, they now occur throughout the Indo-Pacific region and Australia. There, they notoriously pillage ecosystems with their acid-spraying attacks and gargantuan colonies.

On Christmas Island, colonies ballooned to 750 acres as they decimated a local crab species, fundamentally altering the forest understory and now endangering even mature trees.

Conservationists think they might have never arrived in the first place — without hitchhiking.

Hey Antarctic newbie, are you a "fingee" or a "fidlet?" And what are those on your feet — "bunny boots" or mukluks?

If you were a new transplant to Antarctic shores, it would be understandable if you didn’t know. In fact, the people slinging the opaque lingo would prefer you didn’t, according to a researcher who investigated the topic.

But — to get the answers, all you’d have to do is refer to your trusty Antarctic Dictionary.

The manual was part of an opportunistic PhD project by the University of Canterbury’s Dr. Steph Kaefer. On a 2019 visit to Antarctica, Kaefer’s ear for linguistics perked up when she heard veterans dropping what sounded like totally novel words.

What was a fingee, anyway? And why, whenever the topic was ground transportation, did it suddenly swing into the realm of “doo?”

A fingee, Kaefer found out, was an American adaptation of the acronym F.N.G. — an unsavory military term for a “[expletive] new guy.” Brits, on the other hand, called new arrivals fidlets. This was an acronym, too, albeit a more straight-laced one. Falkland Islands Dependency was the name of the British station from which it derived.

Hiding your meaning from newcomers

Kaefer’s study revolved around a core tenet of linguistic synthesis: When you don’t want outsiders to know what you’re talking about, invent slang.

“Often, when we create words, we make them transparent," Kaefer told the University. "Particularly in a situation where you need to pass on a lot of information easily, you want people to understand without needing much background information. But when you’re creating a community, whether intentionally or not, and you don’t want people to understand, you might make the words more opaque so that people can't work them out unless they’re part of that group.”

Because Antarctic communities are so isolated, their offbeat lingo grabs hold even tighter. People working on “The Ice” (as Americans would say) or “South” (British) don’t enjoy open lines of contact with outsiders, whether it’s workers in other stations or their families back home.

Due to this, lingual customs make deep treadmarks.

Which, incidentally, is also a quality of Antarctic “doos” — or snow machines, in British continental slang.

Singing has served as one of the world’s main forms of communication for birds, whales, and of course humans. But a new study shows that at least for one variety of tree-dwelling primate, it’s the same old song and dance.

One specific type of lemur makes sounds that bear a striking resemblance to human song. Because Madagascan indris use vocal rhythms that sync up with some of our most foundational beats, researchers think they might be the link to the origin of human singing.

Of course, many other animals communicate by singing. But the new study, published in the journal Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, explains how indris use a singular rhythmic pattern called isochrony to transmit alarm signals.

Indris have found fame as the world's "singing lemurs." Their squealing, mesmerizing vocalizations reverberate through jungle canopies, especially in the early morning.

Keeping the beat

But they aren't just improvising.

In isochrony, each interval between sounds or notes is equal. This creates a natural pattern or beat, like a clock or metronome ticking.

After the University of Warwick team first noticed the trend in the indris, they set up a long-term study to monitor any patterns. Data collection covered a painstaking 15 years. Beginning in 2005, the team followed 51 indris and listened to them sing 820 different songs, lead study author Dr. Chiara De Gregorio told Phys.org.

When the long serenade finally finished, they noticed a striking conformity. Isochrony is a defining quality of human music, and the large lemurs’ songs showed the same affinity for it. Every single song and alarm call used the pattern.

"This discovery positions indris as animals with the highest number of vocal rhythms shared with the human musical repertoire — surpassing songbirds and other mammals," said De Gregorio.

The results help corroborate a long-standing theory among evolution researchers: that songs indicate an ancient common ancestor between species.

"The findings highlight the evolutionary roots of musical rhythm,” said study co-author Dr. Daria Valente of the University of Turin, “demonstrating that the foundational elements of human music can be traced back to early primate communication systems."

From Frankenstein’s monster to Roy Batty and beyond, humanoid creations have always piqued our fascination.

But the closest we’ve come to bringing the fantasy to life — in real life — is by building robots. Until recently, this strategy hasn’t produced strongly convincing results. Even though a viral tidbit attributed to Stephen Hawking proposed a world where humans would play a role for robots similar to “what dogs are to humans,” it was tough to see us becoming their best friends. Back in 2016, Boston Dynamics’ Atlas robot wasn't very endearing until a YouTuber brilliantly added a human touch in post-production.

Robot capabilities have come much further eight years later, but what’s the next step? How about realistic, human-like skin, like the Terminator?

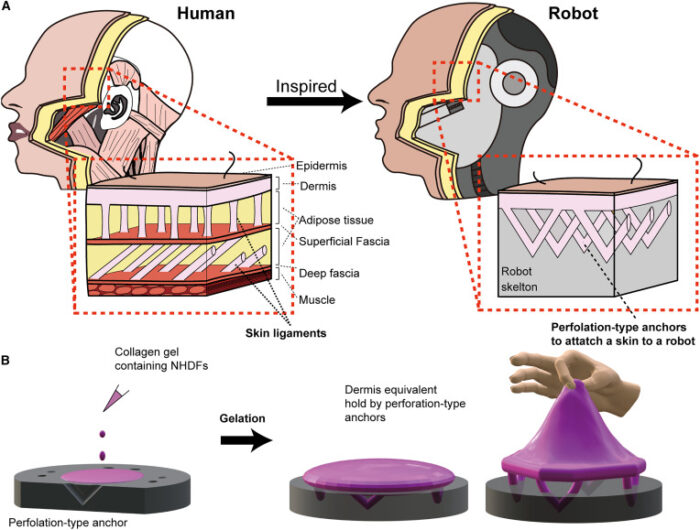

One lab announced new developments in robot skin systems that could significantly blur the line between man and machine.

Healthy 'skin,' wide 'grin'

Cultured from human skin cells and secured with attachment systems based on human ligaments, the new material self-heals and adheres to its frame with a stretchy, rebounding quality. Thanks to a “perforation-type” anchor system, it resists loosening and tearing — which have been disturbing giveaways of robot skin up to now.

The University of Tokyo lab team announced its findings with a June 25 paper in the journal Cell Reports Physical Science. Uncanny photos and video shows the new cultured skin undergoing “smile” tests — a flat “face” stretched onto a metallic chassis contorts back and forth into a mouthless grin.

Material durability and lasting tension are inherent challenges robotics researchers face while engineering skin. The new, cultured product reverses previous anchoring structures that protruded upward from below, attaching to the skin via hooks. Over time, the skin stretched and loosened around the anchoring points.

The Tokyo team’s artificially grown skin, instead, uses V-shaped hooks that insert into tiny perforations in the robot’s skeleton.

To do it, technicians must essentially paint on the robot’s skin. First, they coat the robot with a water-vapor plasma to make it attract water instead of repel it. Lab techs then smear a skin-forming, “cell-laden gel both onto and into” the V-shaped holes in the robot’s structure. The hydrophilic, or water-attractive, skeleton then pulls the skin hooks into the perforations over time.

Testing will continue as the team seeks better durability. They mentioned the skin can self-heal under minor wear and tear, but did not measure the recovery rate. Human skin maintains the distinct edge in self-repairability for now. The robot skin’s developers are looking to mimic ours as closely as possible.

Study co-author Shoji Takeuchi told LiveScience the team is trying to increase the skin’s nutrient and moisture supply, which “could involve developing integrated blood vessels or other perfusion systems within the skin."

Another objective is to increase shear strength. Don’t look for ripstop stitching, though. “Optimizing the collagen structure and concentration within the cultured skin” is the target, Takeuchi said.

You can’t stand in the way of progress. So you’d might as well smile about it — whether you’ve got a face made of bone or titanium.

If 2011 UL21, a mountain-sized object hurtling through space at 93,000 kilometers per hour, hit Earth, things could get dicey.

It won’t, astronomers say — but it will come closer to it than any other celestial projectile in the past 125 years. And it will put on a live show you can watch on the internet or even with a decent telescope.

2011 UL21 makes an official close pass of Earth once every three years. That’s when it orbits within 1.3 astronomical units of the Sun — the criteria for a “near-Earth” asteroid. Near-earth asteroids zip past Earth at a cozy distance of 45,000,000 kilometers or closer.

In this case, much closer.

No chance of catastrophe

2011 UL21 will buzz the tower on June 28-29 at about 6.6 million km. It’s the closest approach the asteroid has made in over a century, according to NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

It’s a moot point because there’s zero chance a collision will occur, the European Space Agency (ESA) reassured, but 2011 UL21 would wreak mass destruction if it hit Earth.

Spacereference.org estimates 2011 UL21’s size to be 1.7-3.9 kilometers in diameter — about five times smaller than the space rock that killed the dinosaurs. First observed in 2011, it’s bigger than 99% of all known near-Earth asteroids.

If an asteroid were the size of a 20-story building, it would be just 3% as big as 2011 UL21. Still, it would rip into Earth with a force similar to today’s biggest nuclear bombs, completely destroying any major city it hit.

Such collision damage could spread to a continental or even planetary scale. For now, though, it will harmlessly delight stargazers by making a close, bright pass.

A livestream by the Virtual Telescope Project (VTP) will broadcast the asteroid’s hurtling progress once it starts approaching this Thursday, June 27. The feed will come from the Bellatrix Astronomical Observatory in Ceccano, Italy.

Surprise twin visitor

Armchair astronomers in the northern hemisphere with decent telescopes may be able to catch a glimpse of it during its brightest period, from June 28-29, according to LiveScience.

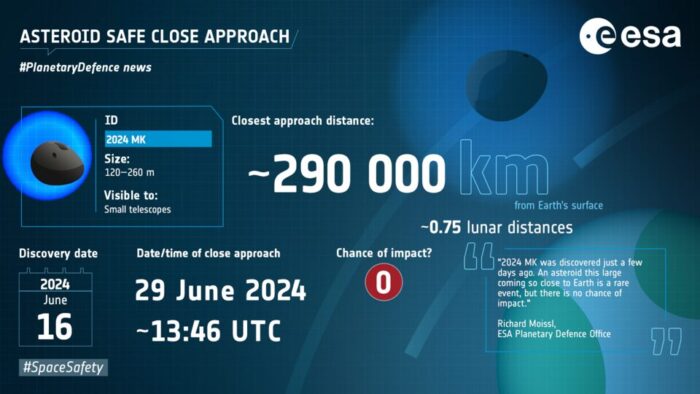

More alarmingly, its arrival will coincide with another massive near-Earth object that will pass — harmlessly — much closer but wasn’t discovered until just days ago.

2024 MK will cruise past Earth at about 290 km. The ESA spotted it on June 16, and its fly-by date is June 29. It is between 120m and 260m wide.

“There is no risk of 2024 MK impacting Earth,” the ESA said. "However, an asteroid this size would cause considerable damage if it did, so its discovery just one week before it flies past our planet highlights the ongoing need to improve our ability to detect and monitor potentially hazardous near-Earth objects."

Safe in a shooting gallery?

Coincidentally, the close-quarters celestial action all leads up to Asteroid Day on June 30. The UN-endorsed event commemorates the largest observed asteroid strike on record: the 1908 Tunguska Event, in which an airburst decimated a largely desolate Siberian region.

If it seems like the Earth is a sitting duck in the shooting gallery of space, well, so is everything else in space. But astronomers now think there’s very little chance an asteroid similar to 2011 UL21 will hit Earth for the next 1,000 years.

Then again, close calls are likely. Keep your eyes on the sky in 2029. That’s when Aphophis, an asteroid named after the Egyptian god of chaos, will visit next. It’s as big as the Empire State Building — and it will thread the needle between us and our orbiting satcom satellites.

It’s a bridge too far to paint Jacopo Larcher as a revisionist. But in European rock climbing, he’s trying to synthesize a future that diverges from its past — and he’s not afraid to confront history in order to do it.

Ask yourself: Would you forgo a bombproof bolt for a marginal cam placement if you were facing a nasty fall?

View this post on Instagram

That’s the game Larcher plays all the time as he barnstorms around his home continent, ignoring bolts on sport climbs. He accepts the hazard as part of an effort to reframe the role of the expansion bolt — the central piece of hardware in a modern route developer’s toolkit.

Making 'the sharp end' even sharper

Larcher is The Traditionalist, in his new role for The North Face as well as in practice. Since the mid-2010s, he’s blazed his own trail through the climbing world by creating specific, hard climbs that would terrify most people.