"The North Shore invented mountain biking," claims Todd "Digger" Fiander, a trail builder and videographer. If the sport was indeed born in , Betty Birrell was there from the start.

North Shore Betty, a short film from Patagonia, introduces us to the eponymous Betty. Now entering her seventies, Betty reflects on what is means to be an older woman in the rough world of mountain biking.

One big playground

She didn't start in mountain biking. Betty first made a splash (pun intended) pioneering women's wave sailing in the early 1980s. By her mid-forties, she was a single mother and full-time flight attendant, but she also started mountain biking. She started riding Fiander's "roller coasters for bicycles" after getting her first mountain bike in 1993.

Rather than competing, Betty found that mountain biking and being a single mother worked together. It became an activity she could do with her son, and they still bike together now that he's an adult.

Betty also isn't afraid to get injured. She's broken an arm, a wrist, a hand, and "lots" of ribs, dislocated shoulders, and torn her rotator cuff, but it didn't, and still doesn't, bother her.

According to Betty, when her ex told her she treated life like it was "one big fucking playground," she took it as a compliment.

The short film interviews Lea Holt, a nurse with a family who worried, as she approached fifty, that she would have to give up mountain biking. But Betty's career changed her mind. "I have twenty more years..." Holt explained, "to get better."

"Betty is a legend on the North Shore," says fellow British Columbia mountain biker Amanda Moffat. When they ride together, she says, people will call out to Betty as they pass, like she was a celebrity.

Now 73, Betty plans to keep riding into her nineties. "Older people...need to know that you can keep going," she says. On the screen, Betty's bike leaps over rocky trails and races around bends and through the forests.

A new film, Everest Revisited: 1924–2024, invites viewers to look beyond the headlines to consider what Everest has come to mean, both in the past and the present. The film, which was publicly released earlier this week, won the Jury Special Mention Award at the 2024 Kraków Mountain Festival and was runner-up for the Audience Choice Award at the 2024 London Mountain Film Festival.

The 41-minute documentary, produced in association with the Alpine Club and the Mount Everest Foundation, weaves together archival footage with analysis and reflection from some of the UK's leading Everest enthusiasts.

Narrated compellingly by mountaineer Matt Sharman and anchored by the personal connection of Sandy Irvine’s great-niece, Julie Summers, Everest Revisited is less a dramatic retelling of Everest history and more a reflective journey through the mountain’s cultural and spiritual legacy.

At the heart of the documentary are the expeditions of the 1920s, with particular focus on the ill-fated 1924 attempt by George Mallory and Sandy Irvine. With contributions from mountaineers and historians such as Rebecca Stephens, Leo Houlding, Stephen Venables, Chris Bonington, Krish Thapa, and Melanie Windridge, the film explores how these early attempts were shaped as much by imperial ambition and scientific curiosity as they were by the challenge of climbing itself.

A critical examination

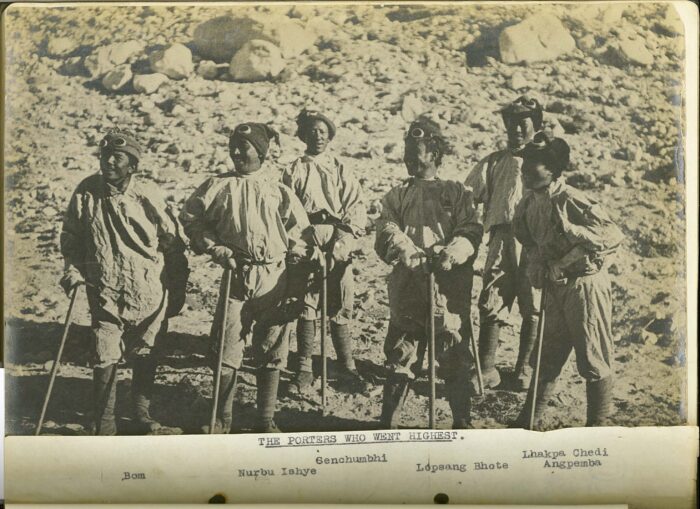

Rather than idealise the past, the film examines it critically. It acknowledges the hierarchy embedded in British imperial attitudes, particularly toward the Sherpas and high-altitude porters who made these expeditions possible. The film highlights the essential, and often overlooked, contributions of figures like Karma Paul and Gyalzen Kazi, who bridged very different cultures. Porters like Paul and Kazi quite literally carried early Everest expeditions forward.

Everest Revisited also looks forward. Blending stories from climbers like former Gurkha Krish Thapa, who helped double-amputee Hari Budha Magar summit Everest in 2023, the film draws links between notions of historic heroism and modern questions of easy access and motivations. Despite the growing queues on Everest’s slopes and its increasingly commercial reputation, writer and climber Ed Douglas suggests that modern climbers may not be too dissimilar to those of the past.

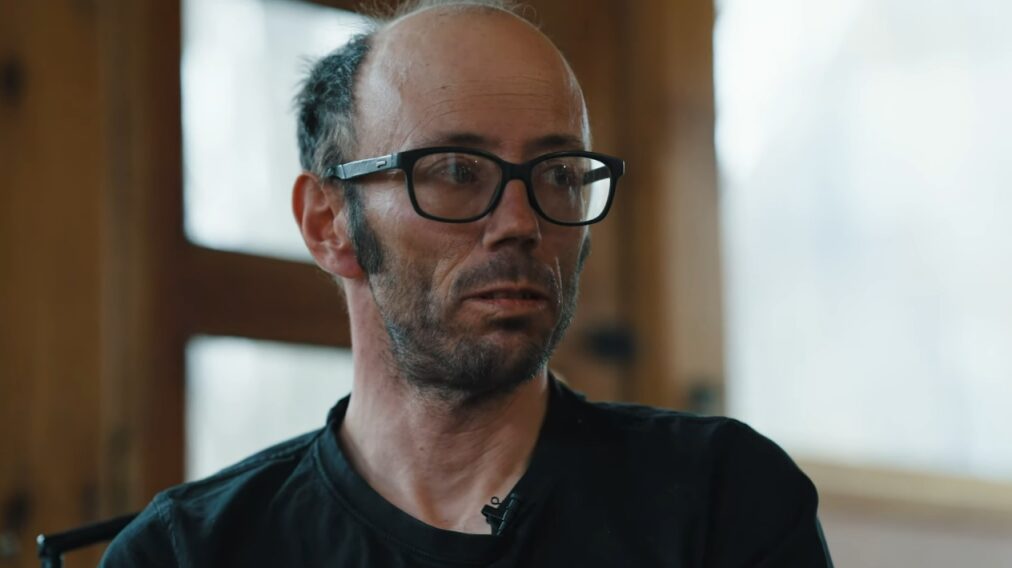

"We tend to think that Everest is kind of somehow more complicated, more cynical, and less illustrious than it used to be. I think we need to look back at these expeditions with a more honest eye, because these are not simple, heroic people. These are people with the same motivations and the same, you know, concerns and the same complexities we have. They weren't always honourable. They weren't always perfect," Douglas reflected.

Emphasizing the unknown

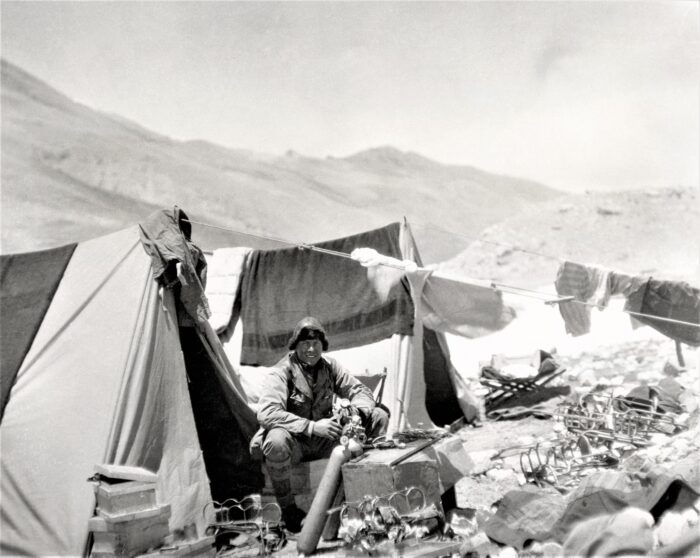

Visually, the film integrates modern and archival footage of Himalayan landscapes with impactful interviews and primary artifacts, such as photos and equipment from early expeditions.

Rather than offering a final verdict on Mallory and Irvine’s fate, the film leaves room for mystery. It emphasizes the unknown. As climber Leo Houlding poignantly tells Irvine's great-niece Julie Summers, "I hope we never find your great uncle and I hope we don't find the camera. I hope that the mystery endures for another century."

Everest Revisited is a film about more than just mountaineering. It’s about memory and the shifting values we project onto the world's highest mountain. The documentary will intrigue climbers, historians, and anyone drawn in by the enduring allure of the world's highest mountain.

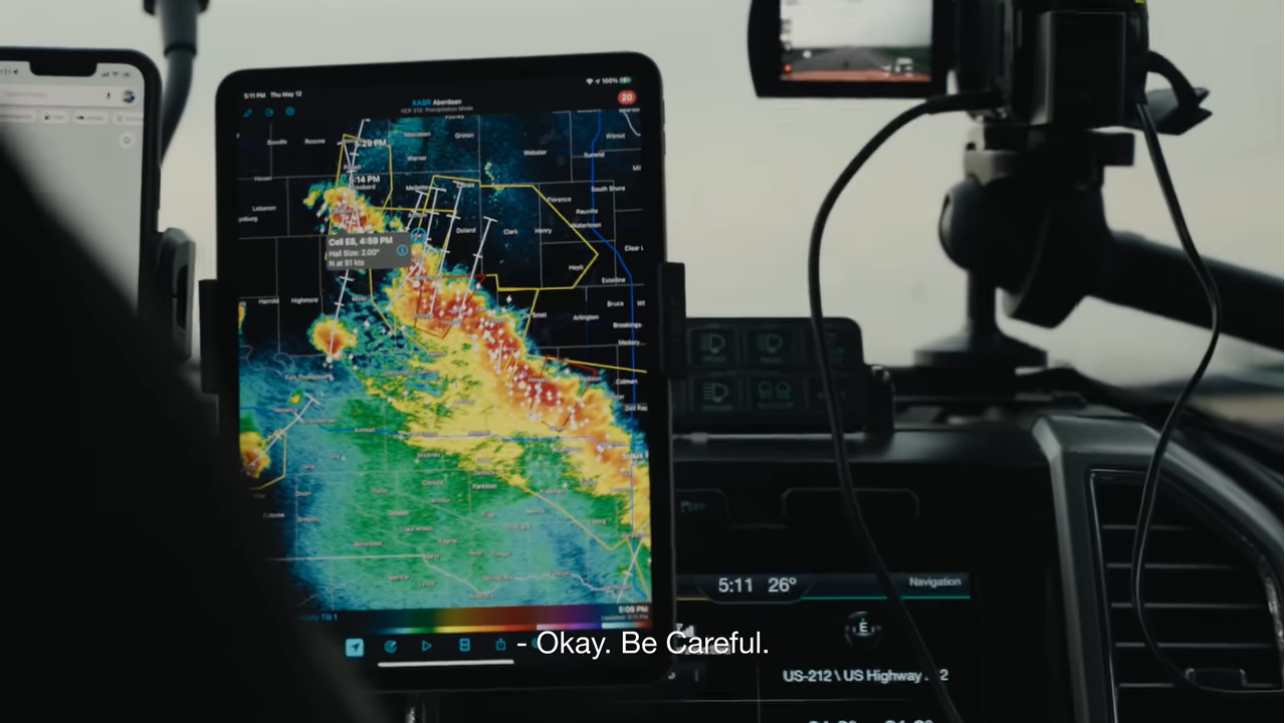

In Tornado Hunting: Chase it From the South, storm chasers Chris Chittick and Ricky Forbes document their lives in the notorious Tornado Alley of the central U.S.

Just south of Sioux Falls, North Dakota, Forbes, Chittick, and their crew are waiting and watching the skies for funnels of violent cloud.

"We are in the right spot!" they crow as a tornado warning comes in only a few kilometers away. The tornado siren echoes through an empty town as dark clouds roll overhead. The unfolding scene is apocalyptic. The air turns green, they lose signal -- but the tornado doesn't appear.

A professional storm chaser is like a sailor of old. The wind and weather are the ultimate deciders of success, no matter their skill or determination. Like the tars, they spend a lot of time away from their families.

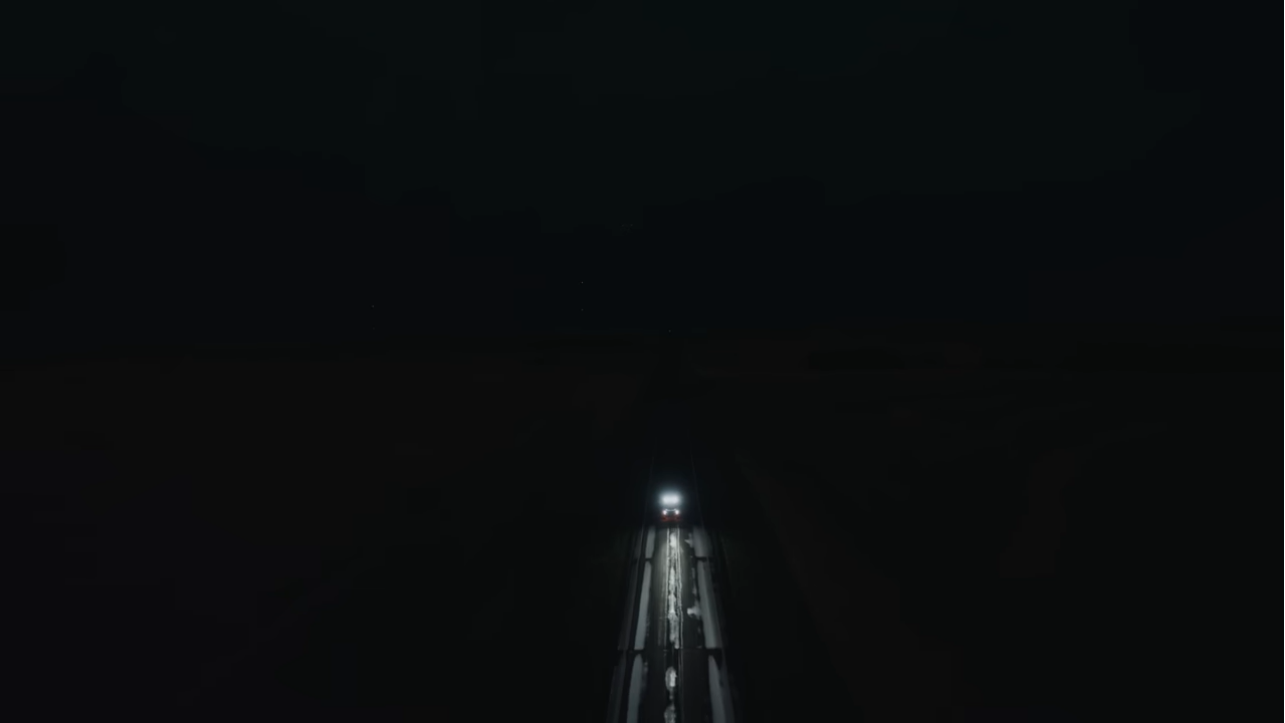

After the disappointing storm, in a rain-soaked parking lot, Chris calls home and tells his children that he misses them. Then it's back on the road.

Home is Saskatchewan, Canada. Chris pushes one of his three young children on the swing, one eye on the darkening sky.

"I feel like weather always wins," admits his wife, Chelsea.

Meanwhile, Rickey and his fiancée, Tirzah Cooper, are driving to her first cancer treatment. She wonders how soon she'll lose her hair.

From the south

A storm is forming around Canby, Minnesota, and the Tornado Hunters drive to meet it. But the road conditions and local terrain complicate their attempt. Hills and tall trees prevent their view and access to the storm. The only chance of getting close is to go right in front of the storm's path, a dangerous gamble. It's safer to approach tornadoes from the south, as the storms move in a northerly direction. Driving into them head-on can, and has, been deadly.

"The more I've storm-chased, and the more that I've seen the destruction that tornadoes can do, the more terrified I become of them," admits Ricky.

They're watching construction crews haul away the wreckage of a ruined house, after the storm they failed to catch has passed.

Their caution brings them back to Saskatchewan, where Ricky and Tirzah go to another appointment. He shaves her head. Not long after, a nearby tornado watch offers what he thinks will be the best chance all year. She urges him to chase after it.

After a succession of near-misses, Ricky finally approaches a dramatic tornado. He stops the car and stands in the road, staring up at the twisting mass dominating the sky. In narration, he says that the feeling he had at that moment was the same feeling of awe he experienced the first time he saw a tornado.

Then, he goes home. " A few years ago," he says, "I never thought anything could be more important than storm chasing. I was wrong."

The film ends with him at home, as on-screen text tells us that both Ricky and Chris continue tornado hunting, and Tirzah is now cancer-free.

BY WILL BRENDZA

When normal singletrack trails and downhill mountain bike parks don’t do it for you anymore, where do you go to get your adrenaline fix?

If you ask GoPro athlete and enduro and freeride mountain bike rider Kilian Bron, he’d tell you to head east to the Himalaya. Bron recently went there in search of some of the steepest lines and most remote mountain bike rides in the world. And he found them.

In this clip from GoPro’s series Draw Your Lines, Bron climbs a 4,600m peak. He carries his bike all the way to the top, traversing a ridgeline as he approaches his descent location. Then, he drops into a chute, fires out onto an open slope covered in scree, and rips his way downhill, with the Annapurna massif in the background. It’s a legendary line — the kind that mountain bikers dream of.

This story first appeared on GearJunkie.

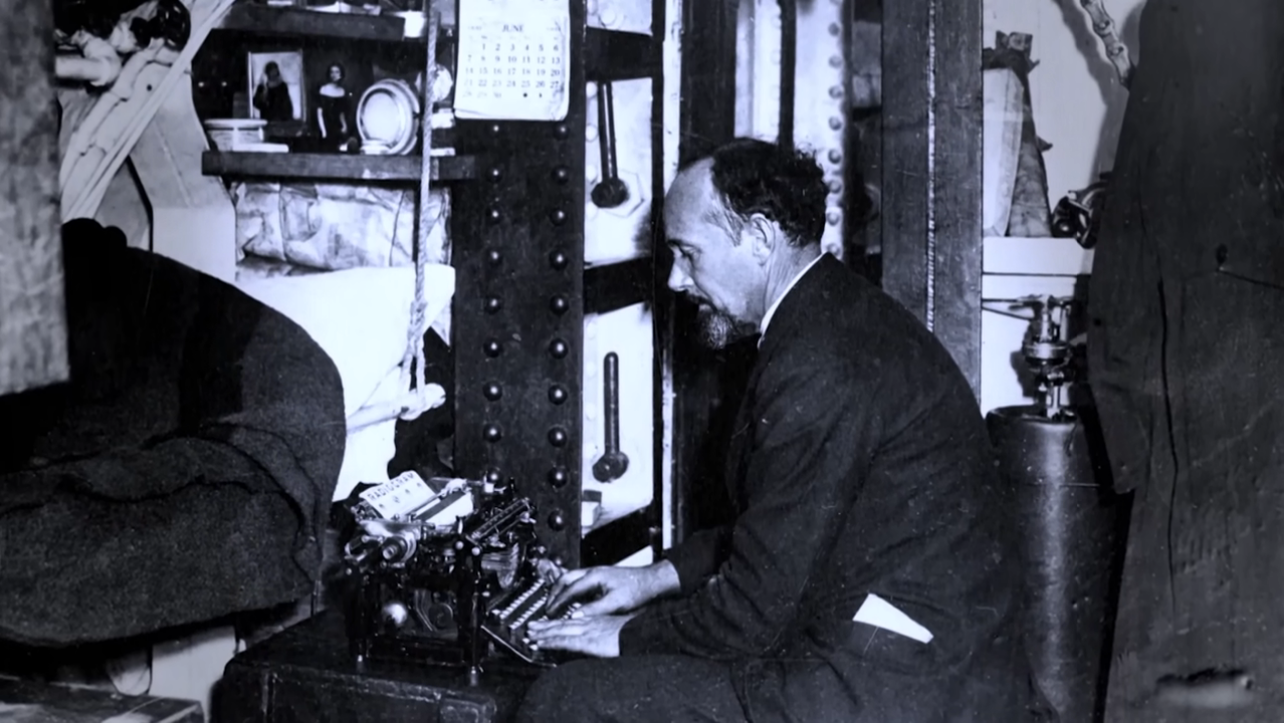

This week's documentary takes us to the frozen Arctic, where a modern expedition follows the route of early 20th-century explorer Hubert Wilkins. In 1931, Wilkins set out for the North Pole in a repurposed military submarine. The subtitle of Frozen North -- "The Disastrous Attempt To Reach The North Pole In A WW1 Submarine" -- hints at how well they fared.

A promising adventurer

Wilkins was raised in Australia. The son of a sheep farmer, he was a self-taught pilot, photographer, and explorer with an abiding interest in the weather. Wilkins first made a name for himself when he flew from Alaska to Spitsbergen, completing the first trans-Arctic airplane flight. He immediately launched himself into the next adventure: reaching the North Pole by submarine.

He chose an old WW1 submarine, which he rented from the U.S. Navy for $1 a year. Interested in his plans, newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst promised Wilkins $250,000 -- worth over $5 million today -- if he could actually reach the North Pole.

Feted in Brooklyn and well-wished by the wealthiest men of the age, the newly christened Nautilus headed North. Wilkins' goals were scientific. He believed, correctly, that polar conditions impacted weather worldwide.

In addition to his meteorological instruments, the ship was fitted with an ice-borer which didn't work, a hydraulic flap to keep it below the ice, and an airlock from the converted torpedo bay. It had no heating or insulation.

The disastrous attempt

Her sea trials went badly, but the season was getting late. It was forge ahead or wait another year, and no polar explorer has ever chosen option two. They left New York with only two months of summer left, with 10,000km to go.

Almost immediately, a storm nearly wrecked them, and the Nautilus sent out an SOS signal. They were rescued and towed the rest of the way to England. Once there, they lost a month to repairs, only halfway to the North Pole. They kept going anyway, making it to Bergen, Norway. Norwegian experts doubted they would survive, and Randolph Hearst sent Wilkins a telegram telling him to call it off. Wilkins ignored this.

It was freezing in the hold, where Wilkins and the researchers conducted observations. They actually did important research, including showing that the Earth is flattened at the poles, instead of a perfect circle. Hopefully, this achievement consoled them through the miserably cold, wet, and cramped conditions.

After doing some science and freezing in the Arctic Ocean, the crew was ready to go home. But that wouldn't satisfy the press, so Wilkins ordered a dive. They were going under the ice.

Under the ice and missing the Pole

Upon inspection, however, Wilkins found the steering mechanism damaged. Historians in cutaway interviews suggest that this was deliberate sabotage by an engineer anxious to go home. Wilkins was unmoved and ordered a dive on the next calm day.

They made it under the ice, becoming the first people to do so. But the radio was damaged, leaving them unable to call for help. At home, newspapers reported them dead.

When they re-emerged, they jury-rigged a radio announcing they were alive. Hearst signaled back that he was glad they were alive and was also cutting off funding. Devastated, Wilkins stayed in the ice for three weeks, taking groundbreaking scientific measurements. It was clear they were not going to reach the Pole.

The Nautilus left the frozen north and limped back to Norway. By the time it arrived, another engine failure had left it unusable. On order of the U.S. Navy, it was scuttled off the coast of Norway.

Diving to the Nautilus

Nearly a century after his failure to reach the Pole, Wilkins' attempt is appreciated as an exploratory and scientific success. But the mystery of the broken steering mechanism lingers.

In a modern two-man submersible, researchers descend to the sunken Nautilus. The modern craft contrasts sharply with the dangerous, dirty, and miserable conditions of the older one, showing how far (with some exceptions) the technology has come.

They found the Nautilus, well preserved in the cold water, but now home to a diverse array of marine life. Researchers focused on the steering gear, looking for signs of deliberate damage. But it's buried in the sediment, preventing them from inspecting it.

Sabotage or not, it was suicidal to dive without those diving rudders, explains oceanographer Raphael Plante. Coming back alive at all was a remarkable achievement.

But Wilkins always dreamed of returning, and proving that submarines were a viable way to explore the North Pole. In March of 1958, a year after Wilkins' death, U.S. Navy submarine USS Skate reached the North Pole. They scattered Wilkins' ashes there.

Later that year, his vessel's namesake, the USS Nautilus, became the first submarine to transit under the North Pole.

Jake Davis is a professional wildlife filmmaker who has recently begun posting what he captures to YouTube. The title of his latest is descriptive: I Left $100K in Cameras on a Wolf Kill. Here's What They Captured. It's a deceptively simple premise. The footage Davis captures is the story of an entire ecosystem and a rare and intimate glimpse into the lives of wolves.

One day, Davis tells us in the introduction to the footage, he spotted a wounded bull elk. Davis realized he had stumbled into the immediate aftermath of a wolf hunt, and was now face to face with the victim. Knowing this presented a rare opportunity, Davis waited and watched. The next day, carrion birds flying overhead led him to the body of the elk.

Setting up the cameras, we get a behind-the-scenes look into the process of professional wildlife filmmaking. Davis explains his setup, placing cameras at different distances and angles to get different shots. To make sure they're on when there's activity, he sets them to be activated when a nearby device registers heat signatures-- living creatures. Then he leaves.

The afterlife of a bull elk

The birds are the first to arrive at the wolf kill. Various corvids hop about the corpse, and even a large golden eagle alights. Foxes join the gathering periodically. But after five days, the carcass is still largely intact -- and no wolves have visited. But they have been spotted close by.

Davis faced a dilemma. The cameras needed to be serviced to ensure none of them had a dead battery or were buried in snow. But if Davis went out to refit them, he would scare away the wolves. Or he could trust luck, hope the batteries held out, and wait. Fate decided for him, closing the road with storms and accidents.

When he finally makes it out, the cameras are covered in snow. And wolves had visited.

Visit of the wolves

Two young black wolves had arrived to feed, then left again. Quickly, Davis replaced the batteries and memory cards on his cameras and replaced them. Two weeks later, he returned again, to a strange scene.

The elk was nearly eaten up and had also been dragged several yards. And one of the cameras was missing. Footage showed the black pair had returned, as had an older grey wolf, and finally an entire pack. They fed on the elk all night, though one of them took a break -- to steal a camera and carry it off.

The wolves carried it away down the hill, biting at the case and the handle. When Davis is able to find it again, however, the memory card is intact, and we get a glimpse of the thief.

The next day at sunset, the wolves return for the final time. As we watch them gnaw at the bones, it is, as Davis says, "a window into a world that's never seen."

In 1954, the Academy gave the award for Documentary Short Subject to the first film in Walt Disney's People & Places series. Titled The Alaskan Eskimo, the film stitched together events in the daily lives of indigenous Alaskan people.

While the language and viewpoints expressed are outdated, the footage represents a remarkable historical document of daily life in an Alaskan community over 70 years ago.

Summer business

The film crew visited in the warmest months and documented the preparations for the coming hunts and colder seasons. We see men building houses, and women stitching watertight coverings for new kayaks.

When the whalers return, the entire community comes together to haul in and flense the carcass of a beluga whale. We see children enjoying muktuk, slices of the skin and blubber of the whale. It's a very traditional food for groups all across the Arctic Circle, and an excellent source of vitamin C. "It has a taste like beech nuts, er, they say," our mid-Atlantic 1950s narrator adds with typical dryness.

Winter underground

The film crew stays on as the winter chill comes in, and the camera moves inside. The home we saw being built in summer, half buried in the earth, is now finished and in use. The people of the village are not idle in the long, cold hours, but busy themselves preparing useful items.

Men carve knives and harpoons, while women sew waterproof raincoats out of dried whale intestines and strands of grass. The people of the village also prepare seal skins for mukluk shoes. The children snatch the cut-off scraps to chew on, grinning widely at the camera.

A break in the weather occasions an outburst of activity. Dog teams set out to replenish stores and gather wood before the full fury of winter returns. We watch as the men harness dogs, load driftwood onto sleds, and conduct a reindeer hunt.

Hunters and fishermen, the narrator reminds us, are in constant danger. If a blizzard sets in while they are so far away from home, they are likely to die. The weather does turn, but the hunter we are following manages to make it back to the village just in time.

Spring is sprung

As winter draws to a close, the villagers prepare for the celebration of spring. Dressed in their best clothes, they come together in the meeting house. There, the filmmakers record a festival celebrating the end of winter. Men dance in masks representing the gods of the sky, the sea, and the land, in order to honor and thank them, accompanied by drumming and singing.

The ceremonial transitions into the farcical as the dancers switch their masks for caricature masks, intended to represent fellow villagers. The audience laughs, rocking to the quick tempo of the drums, as another winter ends.

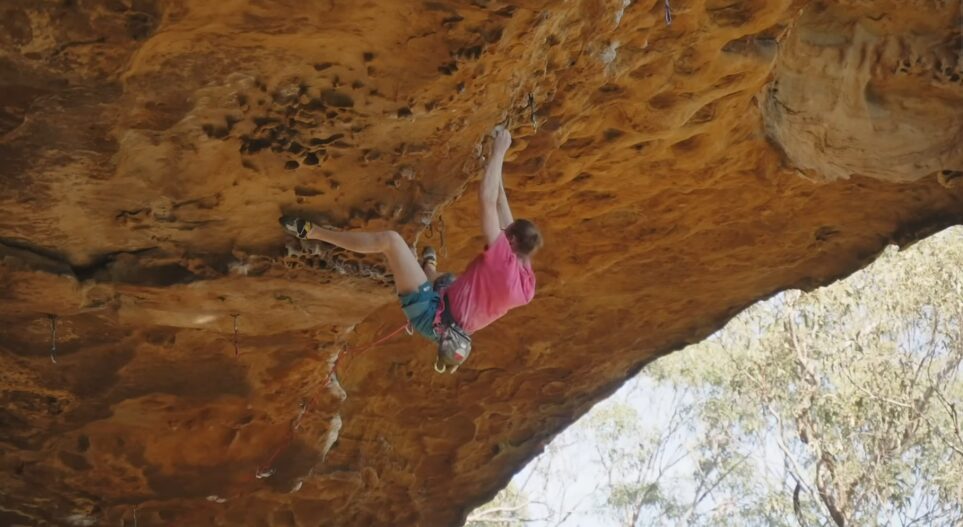

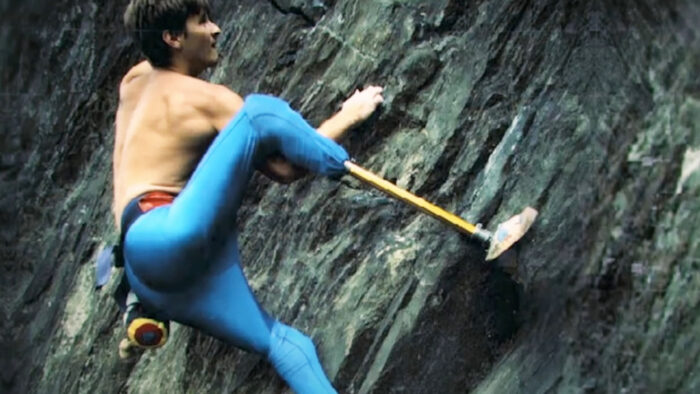

In Five Caves, Five Days, Australian climber Ben Cossey sets off on what he alliteratively dubs "The great Australian coastal cave climbing crawl from Campbelltown to Coolum."

Cossey's been climbing in Australia for more than two decades, but he admits that he hasn't explored much. He has his few favorite areas, and until a friend suggested it, hadn't thought much of climbing north of Sydney. But after looking at a map and finding five promising crags in a line along the coast, he set out to expand his horizons.

Junkyard cave

The first stop is at Junkyard Cave, outside of Campbelltown. Cossey meets up with local climbers who introduce him to a warmup line named Fifty Shades of Mt Druitt.

One of these locals, also named Ben, shows Cossey the main event. It's a line that he and his peers have been working on for a long time, but has attracted little attention from the broader Australian climbing community. Ben hopes they can get more people to try it and appreciate the "little paradise" around Junkyard Cave.

Cossey is game. He manages to send the line, quite literally kicking and screaming, emerging victorious atop a rather cinematic jut of cliff.

"A clean, beautiful rock," he admits, surprised. "Reminiscent of some of the best stuff I've climbed in Australia."

Lobster Cave

Tom is the friendly local assigned to Lobster Cave. In addition to showing Cossey the lines, including one Roast Lobster, they spend some time exploring the area. Close to the coast, the area around Lobster Cave has been inhabited for a very long time. Australian Aboriginal people have carved rock art nearby.

When it's time to start climbing, Cossey first goes for the Red Headed Dragon.

"Not a bad spot," Cossey says with satisfaction. "That's an ideal top out... another coastal cave-crawl classic."

Hoppy's Cave

Another day, another cave. This one is known for being rather sharp. Cossey isn't dissuaded, but he does stop and pick up some analgesic cream in anticipation. His guide today is Jason, who sets Cossey onto Blackleg Miner. The route is long and steep, running all the way from the back of the cave.

"It's pretty radical. It's really radical," Cossey says, impressed. The rock sticks out from the surrounding valley, the only feature like it in sight. It is also, as promised, sharp.

"Man, that is an undertaking!" Crossey exclaims when, hanging upside down bat-like from the ceiling, he reaches the end of the line.

Flinder's Cave

"It's about 400 degrees in the shade," Cossey says, as day four finds him at Flinder's Cave. That's 752 degrees Fahrenheit. Lucy is his guide today, who starts him on Wet Jigsaw Puzzle as a warmup.

Cossey compares her introduction to the cave to being shown around someone's home.

"I didn't know what to expect, but it's better than what I expected," Cossey says.

After "Wet Jigsaw Puzzle" and one other, Lucy sets him onto the grand finale: A Space Odyssey. It's a hard climb, with smoother rock than the other Flinder's lines. Cossey is screaming and panting in the final stretch.

"There's unfinished business there," Cossey reflects. "A lot of routes there to go back to."

Mt. Coolum

Cossey's final day finds him sore and swollen-fingered but undaunted. Krystle meets him at Mt. Coolum, a cave with unique horn-like rock formations.

The strange new style of rock throws Cossey for a loop, to his surprise. The locals, used to the strange surfaces, scurry up the rock where Cossey was struggling, but he keeps at it.

His goal is to finish a route at every crag, and for the first time, there's doubt if he can. As the hours go by, Cossey is running out of time.

Torn to shreds by five days of climbing, his fingers force an end to the fight. This time, Mt. Coolum defeats him. The locals, smiling, are sure he'll be back.

He technically failed the challenge, but resolved his original question: Is there enough good climbing along this coastal route north of Sydney to consider it a climbing destination?

"The answer is, absolutely."

The Mirage follows Timothy Olson as he fights to claim the Pacific Crest Trail speed record. To do so, he has to run 4,270km in less than 52 days, 8 hours, and 25 minutes. This means about 14 marathons a week and about 17 Mt. Everests' worth of elevation gain.

He'll also be accompanied by his pregnant wife, Krista, their two young sons, and Krista's parents, Debbie and Bob Loomis. Trailing Tim in an RV, their family must take care of Tim as well as themselves, always racing against the clock.

Things get off to a rocky start. By day two, husband and wife both recall hitting a wall.

"It's going to bring out the worst of me," Tim admits.

His family provides logistical support, mapping and scouting the trail ahead. Olson is entirely reliant on them to feed and supply him with water. But stretches of the trail he has to backpack alone -- not one of his strengths. But that's sort of the point.

Heat, cold, bears, and snakes

You want ideal conditions, Olson explains, when you're attempting a record. Olson did not have ideal conditions. He hadn't planned for his wife to be heavily pregnant, and he certainly hadn't planned for a record-breaking heat wave.

In addition to the heat, Olson's path is strewn with venomous serpents that rattle and hiss, sometimes from the underbrush and sometimes from the path itself.

Abruptly, the battle with the desert ends, as he crosses the Mojave and enters the Sierra Nevada. Now, Olson faces a different battle. Snowy, rocky slopes cut down on his time.

As the attempt goes on, fate seems to be conspiring against them in a dozen petty ways, all caught on camera. The RV is stuck in a ditch and needs towing, Olson gets injured and lost, and equipment breaks. Because of the then-recent COVID pandemic, trail maintenance is more neglected than usual, leaving downed trees all over the trail.

Climate change affects the run in more ways than the heat. Wildfires rage around the trail, closing aid stations and filling the air with smoke.

Around the halfway mark, a shin injury begins to worsen, slowing his time and causing "excruciating pain" with every step.

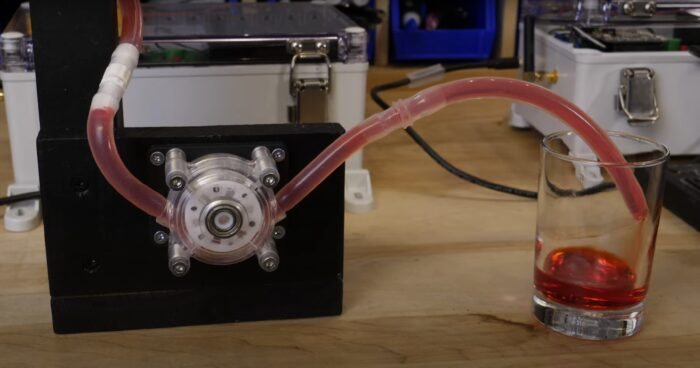

"I miss the whole reason I'm out here...to heal," Tim admits. But he keeps pushing, and his team "throw the kitchen sink" at his injury, trying everything they can think of (other than rest) to keep his leg working. Slowly but surely, the pain starts lessening. His speed picks back up. It still hurts, though.

A family affair

His wife's father explains that running the PCT would, technically speaking, be far easier on Olson without having his family along. "But that wasn't the project."

Bringing his family along wasn't about logistical help. Knowing his wife and kids were waiting in the RV at the end of the day pulled him forward, "like a magnet," during his time on the trail.

Despite everything, Olson triumphs in the end. After 51 days, 16 hours, and 55 minutes, he reaches Canada and the end of the trail. The film ends with a selection of baby photos, and a phone recording Olson made during the run, addressed to his then-unborn daughter.

"Dad is out running...having a hard moment, but it's really beautiful to think of you."

Salimor Khola is a remote valley in Api Himal, nestled between a steep gorge and several unclimbed 6,000m peaks. The ridges and valleys of far western Nepal are far less popular for tourists and mountaineers, a tantalizing lacuna for the latter-day explorer.

This recent documentary, Salimor Khola: A Climbing Expedition to an Unexplored Valley in the Himalaya, follows a team of four as they attempt to explore the valley and summit some of its unclimbed peaks.

It takes over a week of travel -- first flying, then driving, finally trekking-- to reach the area. On the way, we meet the team-- Matt Glenn, Hamish Frost, Paul Ramsden, and Tim Miller -- all experienced mountaineers from the United Kingdom. The area is rural and remote; the people they do meet are surprised to encounter a Western climbing expedition.

The expedition is the brainchild of five-time Piolet d'Or winner Paul Ramsden, a sturdy Yorkshire man in his mid-50s. Ramsden had warned the younger alpinists that there might not be any climbing at all on their climbing expedition. They were going in to explore, not even knowing if they could reach accessible routes. But there was only one way to find out.

They manage to find a route into Salimor Khola, so with a week of food, the expedition splits into two teams: Paul and Tim, and Matt and Hamish. Taking the time to explore also allows them to acclimatize.

The summit that wasn't

After the reconnoitering and acclimatizing, Matt and Hamish set their sights on an unclimbed 6,000'er. After a hard day and 800 vertical meters gained, they bivouac on a ledge cut from snow.

They wake up to snow pressing on all sides, crushing and burying them. The footage goes black, but we hear them swear and pant as they struggle to free themselves and the tent. Eventually, with a half-broken tent and an exhausting night, they try to push on.

But they meet with impassable rock faces and are forced to turn back to base camp. After a day of rest, they head for a second peak -- but exhaustion and heavy snow follow them. The next day, they meet a false summit and a series of avalanche near-misses. But they push on.

Only a few hundred meters from the summit, they stop. The rest of the way is heavily corniced, and another avalanche has just missed them. It's time to turn around.

"There's just something really beautiful about doing this...and then not being able to do the thing that you wanted to do and just having to do it for the sake of it," Glenn observes.

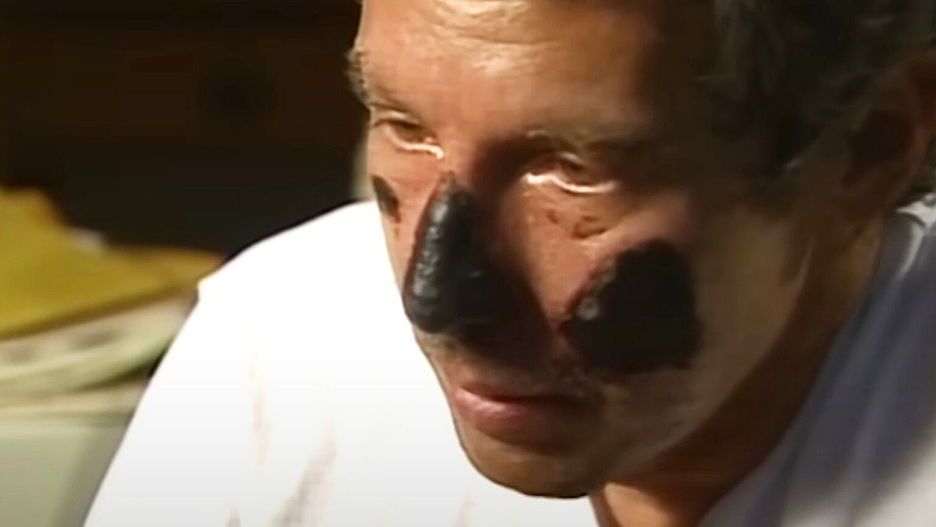

Back at base camp, the pair reunites with Ramsden and Miller. They've made the first ascent 6,605m Surma-Sarovar, although Ramsden's finger is frostbitten.

The film stays with Glenn and Frost at the end of their expedition. They didn't get a summit, but they did do what Glenn calls a "proper expedition" -- an adventure.

"I would love to do more of that," Glenn says. "But maybe just not yet."

Crossing Dreams, subtitled "Solo bivouac paragliding adventure in Himalaya," documents the recent exploits of professional paragliding coach Francois Ragolski. His attempt to follow a long route through and over the Himalaya covered 60 days, four countries, 2,580km and 113 hours of paragliding.

Ragolski has been paragliding for 18 years and planning this expedition for six months. Like him, the movie is anxious to finally start, so it wastes no time launching into the first day of the journey.

It's a solo trip, but he avoids self-isolation, stopping to speak and share meals with the people he passes.

"I thought everybody here would speak Russian," Ragolski says ruefully, when his attempts to find a common language with two hunters in Tajikistan fail. "I was wrong, nobody here speaks Russian." But even with the language barrier, his friendly enthusiasm carries him through.

"Everyone was so welcoming...they load you with so much good food," Ragolski says. Every few days, he meets locals, usually shepherds, who share their food and shelter with him. Left to his own devices, he mostly eats packaged noodles and dried fruit, so a hot meal and friendly faces are a welcome change.

Re-routing

Ragolski spent months plotting his course on Google Maps using satellite images. But when he arrived in Dushanbe, Tajikistan to begin his route, officials stopped him. Government officials, military officers, and tour agency representatives told him the airspace he planned to fly through was simply too dangerous.

They gave him a new route. It was less likely to get him shot down, but it was also longer and more difficult from a technical perspective. The route change lands him in an area heavily populated by wolves and bears, where officials warned him not to stay the night. But the wind and weather conditions ground him, and he passes a stressful night hearing the sounds of animals outside of his tent.

At your own speed

Tired and hoping to avoid confrontations with the local wildlife, Ragolski hitches a ride into Pakistan. Some exceptions for bear and militarized airspace-related dangers aside, he aims to fly as much as possible. Doing that means landing -- and sleeping -- in places he can take off from again in the morning. This makes for some uncomfortable digs, but it's better than walking. "I am lazy," Ragolski jokes.

After the stark beauty of the mountains, the intermissions in crowded urban areas are another kind of striking. Later, a two-week-long spot of rain grounds him in India. He avoids despair through ping pong and a bit of light tourism.

"But as soon as I flew again, I was just so happy," Ragolski says when he finally gets back in the air on day 41. This is a frequent exclamation; his sheer joy at being aloft and moving forward is palpable.

The point of going solo is that he can go at his own pace, taking his time to explore, to meet people, to avoid unnecessary dangers and complications. It's not a race or an exercise in self punishment -- it's an adventure.

In the final days of his journey, Ragolski glides past famous peaks like Annapurna and Everest, marveling aloud. "Wow! What an adventure...I'm so so happy I came."

Gaucho chronicles the days of elderly Patagonian gaucho Heraldo Rial. Gauchos are skilled horsemen and cattle ranchers who have lived independently in the Patagonian region for centuries. Known for their bravery and skill, the gaucho is a sort of folk hero in Argentina. But as modernity encroaches, that ancient way of life is under threat. Rial is one of the last true gauchos.

Now 80 years old, Rial can't do everything he used to. In the summer, three men make their way to the one thousand hectares of wilderness that he ranches. Papo, his nephew Diego, and his son Franco come to help Rial with his tasks. They're the only people who make the days-long journey through the mountains to see Rial.

He spends the winters alone in his little house, bringing his herd down from the mountain pastures to wait out the wind, rain, and snow. Papo compares him to a hibernating bear, tranquil and quiet. But he works every day, tending to his animals and maintaining the house and fences.

"I'm going to die here, at some point," Rial states calmly, as the camera lingers over his home. He seems to be at peace with the idea.

A dying breed

Most of the gauchos that Rial knew are gone now. Increased urbanization, as Papo explains, led gauchos to sell their lands and move to the cities, abandoning the mountain paths and old places.

Cattle ranching is an important part of the economy in Argentina. However, most of that money is made by a long series of middlemen. The men like Rial who work every day to raise the animals earn just enough to get by. In return, they face danger, isolation, and grueling work.

The film shows some of Rial and his helpers' daily tasks, which include finding and chasing down an escaped herd, branding and gelding young steers, and butchering animals.

Papo guides his son Franco, who is learning these skills for the first time. Rial might have passed these skills onto his own son, a friend of Papo, but he died five years ago. "But that's life," Rial says. "And his came to an end. He had to leave."

Rial's way of life is more than specific skills and herding practices.

"One should live without thinking," Rial explains. The way of country people, as he describes it, is one of acceptance. Of death, inevitability, circumstance. It's a way of thinking and living that is alien to modern, urban existence.

"He's the only gaucho left in Patagonia," Papo reflects. "There are no more."

Years ago, Nick Kleer, together with his now-wife, then-girlfriend Kristina Perlerius-Kleer, visited the Tiger Canyon nature reserve in South Africa. They never left. Wild Connection documents their cheetah conservation efforts, as Kleer and Perlerius connect with the famously fast cats living in the reserve.

Cheetahs are critically endangered. In the last century, their population has gone from 100,000 to less than 8,000. Their once-extensive habitat has shrunk due to increased urbanization and farming, leaving them with insufficient hunting ranges.

Anyone familiar with thoroughbred horses or purebred racing greyhounds will know that beautiful, fast animals are often also nervous, fragile, and inbred. The cheetah is no exception. The cheetah population is unusually inbred due to a population bottleneck that occurred around 12,000 years ago. While the paleolithic cheetahs managed to come back from the edge of extinction, it left them with very low genetic diversity.

Hands-on help required

As a result, cheetah breeding programs require very careful management. To save them, it isn't enough to just fence off a piece of land and put a bunch of cheetahs in it, Kleer explains. It requires hands-on intervention by people who can closely monitor their physical and, yes, emotional well-being.

While some conservation efforts emphasize a separation from nature for its own protection, Kleer thinks differently. With industrialization, he says, we have "disregarded...the natural world, to the point that people have forgotten that we are connected."

His cheetah conservation means fostering a close, personal connection with the animals. His particular love for the species began when he first visited Tiger Canyon and met a pair of cheetah brothers. He'd only hoped to get a good view of them, but the pair approached him, purring, and invited him to pet them with friendly headbutts.

Since then, Kleer has spent much of his time in the bush with cheetahs, forming close friendships with several of them.

Tiger Canyon's cheetah reserve covers 970 hectares of bushland. Its inhabitants are Mara, her four cubs, her sister, and an adult male cheetah. Kleer recounts Mara's story, explaining how her anxious, shy personality transformed after she had her first cub.

"She's a very gentle soul...she truly enjoys our company," Perlerius says.

Mara will even bring out her cubs to spend time with the human visitors. The cubs' father is Mashai, who was raised in captivity and had to be taught how to hunt. Now, however, he is successfully living on his own in Tiger Canyon.

Saving the cheetah will help restore the entire ecosystem, Kleer explains, from the antelope on down to the plants. In the same way, the cheetah is connected to the ecosystem, people are connected to cheetahs.

Since the Tiger Canyon cheetah conservation program has started, they've released ten individuals into the wild, several of which have gone on to have cubs.

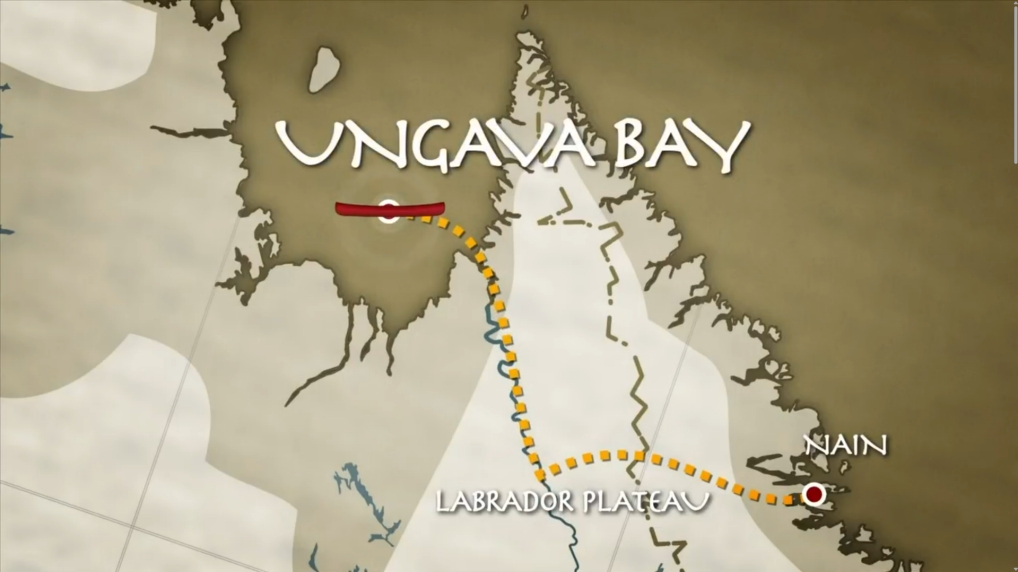

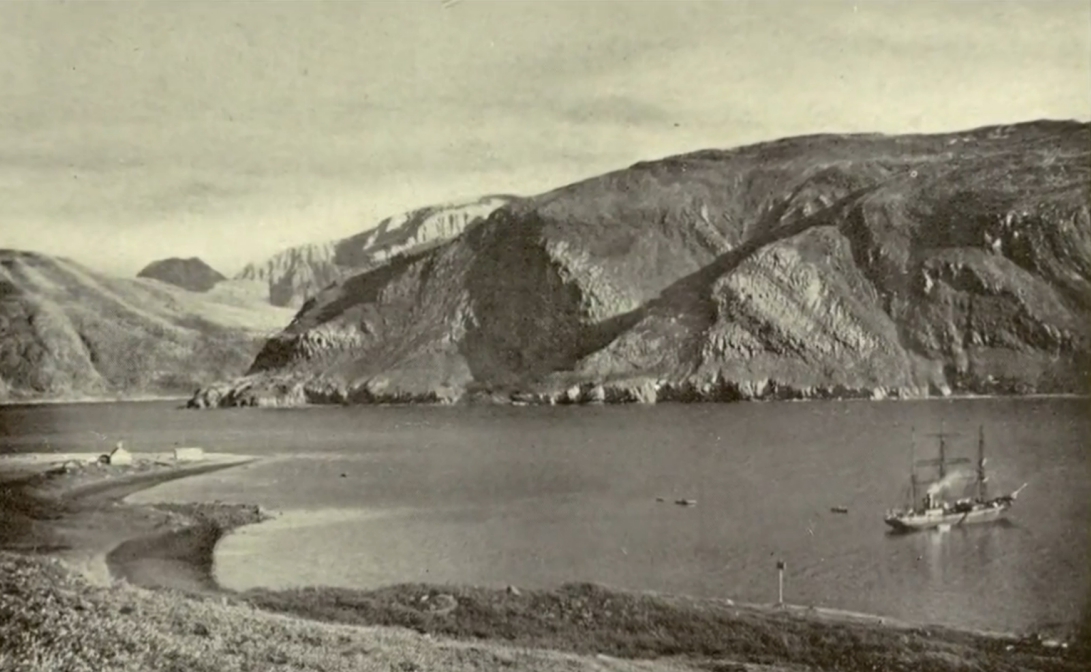

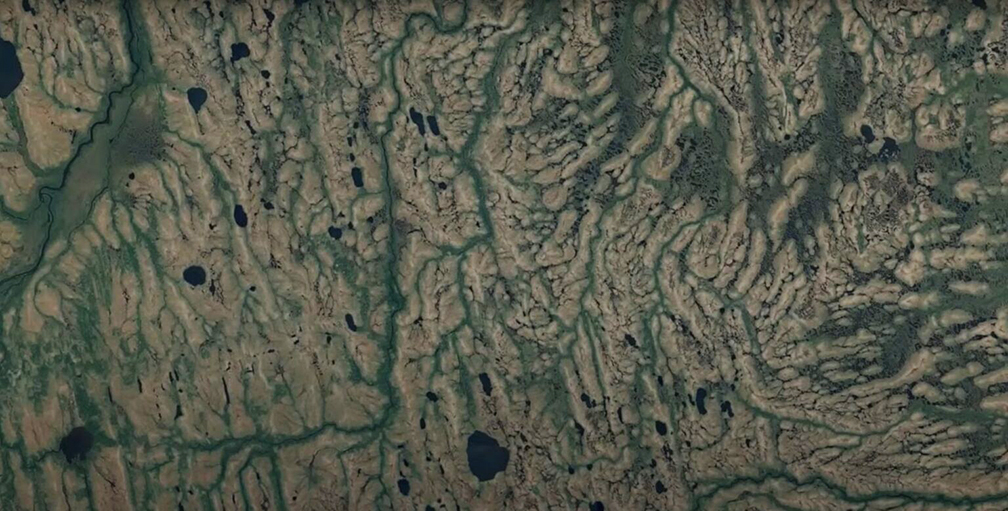

Kitturiaq chronicles a 620km canoe expedition across the Labrador plateau down the George River in Canada's northern Quebec. Professional adventurer Frank Wolf undertook the journey with partner Todd McGowan.

Wolf is bold in adventure planning and is perfectly willing to be bold in filmmaking, too. The film's narration is delivered by a fictional mosquito who chooses to tag along as an unofficial third party member. In fact, the Inuktitut word for mosquito gives the project its title.

Meanwhile, the Kitturiaq, named Malina, shares the story of explorer Hesketh Hesketh Prichard. (Evidently, his parents felt that one "Hesketh" wasn't enough.) Through Malina's narration, the story of the Briton's failed 1910 attempt to complete the route unfolds simultaneously to the main action.

The journey begins in Nain, now the northernmost town on the Labrador coast and the administrative capital of the Inuit region of Nunatsiavut. There, Wolf interviews local community leaders about the land his upcoming journey will take him through.

A 600m climb, with canoe

The first stage takes them a little north to the giant Fraser Canyon, which they must scramble up to the Labrador plateau. Malina's blackfly relatives are thick in the air, just as locals warned they would be.

But it's the portage they have to make that is the real killer. With no waterway to follow, they have to unload their gear, then drag it and the canoe 600m up a crack in the cliffs called Poungassé to the top of the plateau. Sweat and blood cover them both by the time they reach camp, and McGowan suffers sunstroke. The long subarctic summer day can be blisteringly hot.

They're still doing better than Prichard, who took a steeper route and ended up abandoning one of his canoes. Atop the plateau, Prichard saw no waterways -- the plateau is mostly swamps and shallow ponds in this area -- and abandoned his last canoe, continuing on foot. Wolf and McGowan elect to drag theirs. After a brief descent into fly-induced madness, they're back on the water.

"People have been here, a long, long time before us," Wolf reflects, examining a piece of wood. No trees grow on the tundra, so an Inuit hunter must have brought the discarded log on his sled, or komatik, years before. This small moment is a quiet reflection on a core theme of the film.

The paddling and portaging continue. "They're beginning to act a little strange," Malina notes. A headnet makes a reappearance.

When they make it to Nunavik, they go fishing, while Nain politician Johannes Lampe reflects through a previous interview about how prohibitively expensive food is this far North. Caribou is much more cost-effective than groceries, and fishing is cheaper than buying fish. The land takes care of you, Lampe explains, when you take care of it.

The George River

When Prichard and his team reached the George River, they hoped to meet the local Innu people. But these elusive people had already passed on to different hunting grounds. Without any canoes to handle the George River, Prichard had to turn back.

But Wolf and McGowan's portage drudgery paid off, and they still have theirs. Once they reach the George River on day 17, the kilometers begin to fly by. Speaking of flies, they remain innumerable. Soon, the canoeists reach the end of the river at Ungava Bay.

Llanberis in Northwest Wales is dense with routes that give the region arguably the best climbing in Britain. But ascending the lines of the green and grey Cymru hills is more than just technical. Adra, a new documentary, delves into the long history of Welsh climbing and its importance to local identity.

Friends Lewis Perrin-Williams and Zoe Wood grew up on the cliffs of Llanberis. Together, they take the viewer along on various iconic local climbs, like the Left Wall of Dinas Cromlech. When it was first ascended in 1956, climbers wore heavy boots and used railroad ties for protection. A fall meant a serious injury at best.

Lewis's father, mountaineer and author Jim Perrin, recounts the neglected history of native Welsh climbers. Recorded first ascents during earlier eras went to famous English climbers like Noel Odell, who used the hills of Wales as a proving ground before moving onto the Alps and Himalaya. But local Welsh copper miners were the true pioneers of many routes.

Devil-may-care attitudes

Older climbers like Jim Perrin draw a connection between the daring, "devil-may-care" attitudes of climbers in the 1980s and the rise of Margaret Thatcher. Thatcher's tenure is remembered with intense hatred in Wales. Her economic policies left millions unemployed, and the violent police response to the 1984-5 miners' strike shocked the nation.

Adra explores how climbing was counter-cultural in 1980s Wales.

"My climbing came from not being subject to social conditioning," explains John Redhead. Many of the young people in the area were out of work. They started climbing as a way to escape their daily anxieties.

Lewis explains that climbing isn't just a sport but a way of celebrating and communing with his homeland. Adra means "home" in Welsh, a language that was illegal to speak in court until 1942. Celebrating the Welsh language, heritage, and, yes, climbing history is an act of resistance to centuries of British rule.

Climbing, Adra explains, is ancient and indigenous in Wales. But it also nourishes an immediate, living community.

This short film examines what it means to be a snowboarder who isn't social media famous. Now I know what you may be thinking: Why even watch a film if the subject is cloutless? Well, he does fight fires, if that sweetens the deal for you. Snowboarder Joe Lax is not a household name and doesn't want to be. Dark Horse explores exactly what that looks like.

Documentary photographer Brad Slack discusses his subject's elusive, quiet nature. The film opens in Slack's studio, and we first see Lax through his lens. Then, we hear from fellow snowboarder Joel Loverin, who stumbled upon Lax's enigmatic Instagram account.

Whiskey Tahoe

Under the name Whiskey Tahoe, the account posted clip after clip snowboarding steep lines, all without any locations or personal information. Social media comments fill the screen with requests to know more -- where is he, who is he?

He's Joseph Donald Lax. Born to a Saskatchewan farming family, he left home as a teen. He went to Whistler, British Columbia, then a hub for snowboarding culture. There, film companies lurked, creating compilation tapes of the most impressive athletic feats. This is the culture Lax came up in.

But he wasn't interested in going with the crowd. Lax gets up early, what he calls "psycho early," to ensure he is the only one on the mountain. Often, he finds and rides new lines in places no one else dares to try.

Part-timer

Being an underground legend is technically only a hobby, though. By day, he's a firefighter.

"I never saw snowboarding as a career pursuit," Lax explains. He started firefighting as a means to support his time in the mountains. Work hard in the summer, and take the winter off to snowboard. Over the years, though, he's worked his way up to an operations chief. He has seen fire season grow fiercer and fiercer, threatening the mountains at the center of his life.

Something else came along, too, to threaten the primacy of snowboarding -- a wife, Ulla Clark, and two daughters. Instead of choosing between family and the mountains, he brought his family to the mountains. The four of them live in a cabin, and he taught his daughters to snowboard and go on backwoods adventures.

Lax snowboards purely for the love of it and has built his life around it.

"it's 'till the wheels fall off," he promises. His friend Joel thinks they'll be riding the slopes together as old men.

North to Nowhere is the funniest film about North Pole expeditions that you'll ever see. Polar explorers have always taken themselves very seriously, but luckily Montreal filmmaker Josh Freed took a bemused perspective on the crazy cast of characters vying to reach the top of the world one spring back in the late 1980s.

At that time, modern North Pole expeditions were in their heyday. In 1986, American Will Steger and his party made the first unsupported dogsled trip to the Pole. That same year, Jean-Louis Etienne of France skied the 760km alone. (Earlier, in 1978, the great Japanese adventurer Naomi Uemura had reached it alone using dogs.)

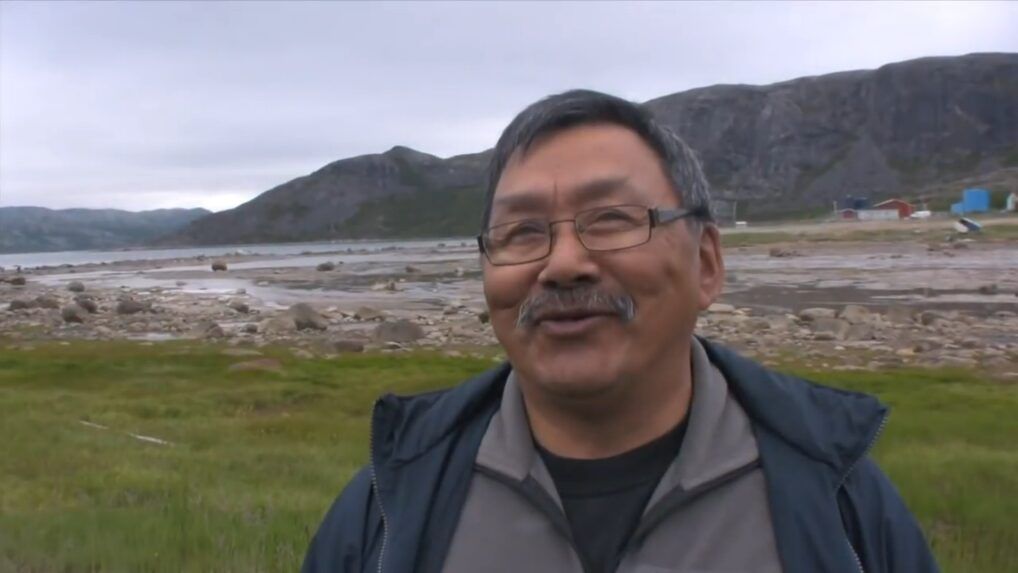

These were serious adventurers, but every year, several less prepared travelers also showed up in Resolute Bay, Canada, touting their great plans to reach the North Pole in various creative ways. Resolute's beloved outfitter, Bezal Jesudason -- featured in the film -- provided logistics and tried to advise them as best he could. Jesudason, who improbably came to the High Arctic from India, used to joke that he himself was planning an expedition to the North Pole by elephant.

Do you need oxygen?

In this pre-internet era, information about the North Pole was not as easy to come by as it is today. Some would-be polar explorers would phone to ask if they needed to bring oxygen "that high up." One British man imagined that he could walk about 80km a day over the broken surface of the Arctic Ocean and was going to show up with just 10 days' food to reach the North Pole. "He was even so generous as to bring two days' extra for bad weather," Jesudason later told me. Luckily, the outfitter managed to dissuade the man from coming.

Scandinavians were usually competent, but one spring, two older Swedes showed up in Resolute with no idea how to use a camp stove. Unable to melt water during two brief shakedown trips near Resolute, the experience so humbled them that they went home without even beginning their expedition. Others spent thousands of dollars to charter an aircraft to the north end of Ellesmere Island to begin but quickly realized they were in over their heads. Typically, they called for a pickup a few days later, citing back injuries as a convenient excuse for quitting.

An influencer ahead of his time

The expeditions profiled in North to Nowhere belong to this zanier crowd. Two French pilots/gourmet chefs set out to fly their canary-colored ultralight plane to the North Pole. There was Shinji Kazama, a Japanese Yamaha salesman who -- heavily supported by Inuit with dogsleds -- took his motorcycle to the Pole. Then there was Dick Smith, the founder of Australian Geographic magazine, who sought to go there in his helicopter. The extroverted Smith was a visionary who anticipated the selfie/Instagram generation and walked around holding a lightweight movie camera pointed at himself and breathlessly narrating the adventure that was about to unfold.

With admirable restraint, North to Nowhere documents the goings-on during this brief Golden Age of what people in Resolute used to call the Silly Season.

Climate change, politics, and difficulties chartering aircraft have ended the hijinx for the time being. The last full-length North Pole expedition was in 2014.

This spring, Tyler Andrews hopes to summit Everest in 16 hours from Base Camp without supplementary oxygen or Sherpa support. The 34-year-old American is no newbie to Himalayan records. He is one of a growing number of climber-athletes who are bringing their mountain running skills to the Himalayan peaks, aiming for FKTs (Fastest Known Times).

Manaslu before Everest

It likely wasn't a coincidence that when Andrews announced his Everest FKT project earlier this week, his sponsor La Sportiva released 9 Hours on Manaslu, the film about his FKT on Manaslu last year. Andrews ran from Base Camp to the top of the eighth-highest mountain on Earth in 9 hours and 52 minutes, beating Pemba Gelje Sherpa's previous record. Andrews was also racing up the peak in 2023 when Pemba Gelje summited. But that year, Andrews didn't feel well on the upper sections and turned around without summiting.

Back home, Andrews had to deal with a badly damaged Achilles tendon, which required surgery. It took a lot of rehab and training before he finally returned to Nepal and broke the Manaslu speed record 12 months later.

For that reason, Andrews sees his Manaslu climb as "a story about failure and redemption," he told ExplorersWeb.

Fall and rise

The film also shows Andrews' personal transformation from a kid interested in math and music to an elite long-distance runner. He dealt with depression but bounced back when he discovered the wild world of mountains and open spaces on Ojos del Salado in Chile in 2020. He began to travel the world in search of thin air, high summit views, and fast times.

Andrews' regular climbing and running partner, Chris Fisher, did most of the Nepal footage on this film. Yet the most intense sequences are those from Andrews' headcam during the ascent: his feet on the frozen ground, his gloved hands on the fixed ropes, and his shadow reflected on the ice seracs. When the runner lifts his eyes, we also see views of Manaslu, a strikingly beautiful peak.

The film will provide a great background for those interested in following Andrews' upcoming Everest expedition and want to understand what's behind the feat and the character.

To learn more about the film, you can listen to this episode of Andrews' podcast, Talking with My Dad. In it, he discusses the challenge behind the scenes and shares details about his physical and mental training with his real-life dad, Tim Andrews.

Painting the Mountains documents the work of Matthew Tufts, a photographer and journalist, as he attempts to capture the mountaineering exploits of his companions.

In Patagonia, climbing is well-established. But the stark granite faces hold little snow, and skiing is more rare. The lines are dangerous -- and spectacular.

Matthew's goal was to follow high-level French skiers Aurel Lardy, Vivian Bruchez, and Jules Socie as they made new descents in the legendary Patagonian Andes.

Painters and Conquistadors

Matthew explains that Renaissance painters could spend six months just mixing the colors they used for a painting and another six months preparing the canvas. His photographic work in Argentine Patagonia was similar.

He first visited the town of El Chaltén years earlier, staying for three months to write an article. He self-funded the trip, determined to establish a connection with the place and the local people. Matthew was wary of coming in like a "modern-day conquistador," exploiting the land for his own gain.

Throughout the expedition, Matthew considers how he might give back to the community and the people who live at the foot of the famous mountains.

A new way to look at it

The skiers bring their own artistic vision to the slopes. The descents they attempt are extreme, dangerous. They see a path where others see only a cliff. Matthew describes one such line as "a thin ribbon painted across a wall of granite."

Through Matthew's camera, the skiers boldly carve their way through the mountains, across never-before-attempted slopes. Local legend Max Odell, who has been skiing El Chaltén for many years, says that the new perspective of the Frenchmen gives him his own new perspective. They see lines where he hadn't dared to imagine skiing, and it inspires him to get back out there.

Max Odell is known as the Godfather of Skiing in El Chaltén. Matthew is proud that they are inspiring him to return to his passion.

The second descent

The climax of their expedition is making the second-ever descent of the Whillans-Cochrane Ramp on Aguja Poincenot. The late extreme skier Andreas Fransson made the first descent in 2012. Descending the steep, exposed line is both dangerous and difficult.

After a hard climb, however, they turn and ski down the ramp, emerging unharmed at the bottom. Matthew, looking on, sees them as artists. They are, he says, "painting the mountain."

The camera pans up a minimalist landscape of snow and stone. Jagged spires stab into the air, their dramatic profiles accentuated by the sharp drone of a male voice singing wordlessly. It might be the beginning of Meru -- until the throat singing cuts out, and the narrator says, "My bad, little something in my throat."

The Crystal Towers: a Yukon Climbing Story is one of three projects funded by the Yukon government for its 125th anniversary. This elegant short documentary is part climbing film, part lighthearted travelogue, and part advertisement for the sparse beauty of Yukon.

Radelet Peak

One hundred and twenty kilometers south of Whitehorse, Radelet Peak lurks above a small lake, still mostly frozen in July when the documentary was filmed. Only one of the team, self-professed flamingo fan Zach Clanton, had made the trip before. Clanton conceived of a new route up the knife-edge arete on the mountain's east side.

But bolting a new route would take hardware, and getting hardware to Radelet Peak would take a helicopter. Where might a "quintessential climbing dirtbag," in the words of his climbing partner Rob Cohen, acquire many thousands of dollars for such a flight?

The government, as it turned out. With support from the Yukon125 fund, four climbers set out with a drone, a carton of Metamucil, and (almost) enough gear to bolt a new route.

The route

The Crystal Towers starts gently as its protagonists tackle the ridge à cheval. The slope isn't steep, but we are frequently informed that it's wickedly sharp, and they would rather it weren't so sharp, thank you very much.

Then the first headwall flaunts up above them, and the documentary comes into its own. Climber and filming lead John Serjeantson effectively uses his drone for striking panoramas. One features Dave Benton nestled in a massive maw of rock just under the subsidiary peak.

Most of the route is crack climbing. Both finger cracks and hand cracks snake up seemingly impassible granite walls. Unfortunately, most of this climbing didn't make it to camera.

It's in close quarters that The Crystal Towers struggles: only a few short sections of GoPro footage supplement the wide shots, and the team largely did not record leads from below.

The lack of footage confuses the narrative. One climber taps out of summit day, referencing difficulties on the route never shown onscreen or explained to the audience.

But while it's clear that these are more climbers than documentarians, that doesn't stop them from creating a lovely film. The shots are clean, showcasing the splendor of the landscape, and the narration brings the audience along on the most exciting pitches. It's always a good sign when a video leaves you wanting more instead of less.

The film meets its goals

As for whether the team sends the route, you'll have to watch and see. But the bolting they carried out will allow a new generation of climbers to explore this region. Said Zach Clanton, "Our goal was to create somewhere that people can walk in with just a rack and a rope and have a super good time, and explore a part of the Yukon they never knew existed."

And as a promo for the beauty of Yukon, well, halfway through, I was already googling plane tickets.

Thirty-two-year-old professional cyclist Lachlan Morton holds the record for the fastest lap of the Australian mainland by bike. The previous record holder rode the entire 14,210km coastal route in 37 days. Last year, Morton completed the same circuit in only 30 days, riding an average of 450km each day for a month.

The Great Southern Country is a film about the process -- and struggle -- of setting that record.

While the biking effort was Morton's alone, a small group of family and friends drove a little blue RV alongside him to provide support.

His wife, Rachel Peck, embraced her husband's newest and most ambitious adventure with cautious enthusiasm. Tom Hopper served as Morton's dedicated bike mechanic, and Athalee Brown as Morton's masseuse.

Morton's elder brother Angus, with videographer Scott Donald Mitchell, filmed it all. Angus had cycled professionally himself, but in the past decade, he has turned to the camera. Finally, Graham Seers, Morton's coach since childhood, rounded out the team.

Ice baths

The timeline was incredibly ambitious, even if nothing went wrong. So, of course, things went wrong. Only days into the journey, Morton became ill with food poisoning. Undeterred, he continued cycling that day without eating, determined to maintain his daily goals.

The team gently attempted to convince him to slow down, but Morton kept to the schedule.

Luckily, Morton bounced back quickly. But as the days went by, even the best-conditioned body and the most determined mind began to falter. His legs became red and swollen, and increasingly, he spent his time off the bike in ice baths. When heat and strong headwinds made conditions untenable, the team struggled to convince Morton to stop.

"You always want to push... to see what you're capable of," says Morton. "That's the whole point of doing it."

More immediate dangers also arose. The most notable was from traffic. In one harrowing moment, a truck drove Morton off the road. After several close calls, they altered the route to avoid major highways.

While he sometimes didn't stop even to eat, Morton did once pause to help an injured bird off the road.

Understanding the land

The journey wasn't just a test of endurance. For Morton, born and raised in Australia, it was as much about the land he would be covering as it was the distance. The ride is about "understanding where I'm from."

This meant engaging with the indigenous people. The film includes several sections of narration in Indigenous Australian languages and highlights the people and cultures of each region.

A New Way Up shows two mountaineers combining climbing and paragliding in a novel way on a previously unsummited Karakoram peak.

Fabi Buhl is a German climber, Will Sim is a British alpinist, and Jake Holland, a pilot and filmmaker, is the narrator. The itinerary integrates all their skill sets.

Buhl and Sim are shown going over equipment, comparing different clips, carefully weighing gear, and debating every detail. Their expertise and careful planning are on display.

Gulmit Tower rises 5,801m to form a rectangular jut of granite, powdered with snow. Previous attempts to reach the summit have been unsuccessful. Those earlier attempts all approached from the opposite side, from Gulmit village. As Holland lays out, their expedition will attempt it from the south side by paragliding onto the tower and then climbing the final stretch.

A comfortable base

The expedition based itself in the green and comfortable town of Karimabad rather than a freezing tent camp. If the paragliding is successful, it will turn a strenuous hike of many days into an hour-long flight. But once in the air, they are at the mercy of the weather.

The flight is tense, as winds change in a moment and separate the three paragliders. This time, though, they were lucky and managed to reunite on the mountainside despite the fluctuating thermal. And just like that, they’ve skipped not only the drudge hike but the first two-thirds of the mountain. They make camp while dramatic drone footage emphasizes the remote location they’ve reached after only an hour of travel.

This is still a climbing expedition, and they’re up before dawn, ready to make their way to the summit. Voiceover is minimal as Will and Fabi, appearing as tiny dots on a sheer face, inch up the tower as Holland tracks their progress.

Around noon, they reach the summit. Fabi and Will seem struck by the surreality of their approach. “Twenty-four hours to climb basically a 6,000m mountain…starting at 2,500m in a hotel, without a helicopter,” Will says.

“It’s pretty crazy,” laughs Fabi.

A new era?

From the summit, they return down to the tent, don their wings, and prepare to take off. The danger, however, is being unable to get off the mountain. While Jake and Will make it to the hotel, the wind changes and leaves Fabi stuck in the Gulmit basin and alone on the glacier.

After hours and many attempts to take off, Fabi manages to get airborne and successfully lands, but his perilous situation reminds us that their novel technique has its downside.

The film ends on a triumphant note, as the trio enjoy the amenities of their hotel only hours after being the first to summit Gulmit Tower. Whether their “new way up” has the potential to change exploratory high-altitude alpinism is up to the viewer.

In a small wooden cabin on Mt. Washington, one caretaker resides alone. This short film introduces us to Jack Kingsley, a young man who cheerfully signed up to live on an isolated, frozen mountainside in New Hampshire.

Everything you need, nothing you don’t

Kingsley savors the independence and self-reliance of the caretaker’s life. The camera follows him through his day, gathering snow to melt into water, cleaning and repairing the cabin, and cooking for himself. The life offers, he explains, “everything you need, nothing you don’t.”

This simple life, he says, allows him to appreciate the little things. The peace, as well as the power, of nature.

Kingsley spends much of his time in nature. He’s a passionate ice climber, hiker, and backcountry skier. Few other occupations would give him this much time or opportunity to indulge in his passions. But at the end of the day, his life revolves around the old cabin.

An old dirtbag of a cabin

“If the cabin was a person, it would be a dirtbag,” Kingsley says. “An old dirtbag.”

The old dirtbag was built in 1963 by Harvard undergraduate students. They were members of a mountaineering club without any background in construction, but park rangers agreed to let them build a cabin. Things were different in the 1960s.

For decades, the cabin and a lone caretaker have acted as a waystation for hikers and climbers on the mountain. It is the nexus of the mountaineering community on Mt. Washington. This means that cold, lost, and hungry strangers might at any moment break the isolation in which Kingsley lives.

“Anyone can walk through that door, and that’s part of the beauty of it,” Kingsley says happily. Rather than isolating, the cabin seems to present an opportunity to connect. With the strangers who pass through, with the history of Mt. Washington mountaineering, and with his own father.

Aged photographs are projected over Kingsley’s voice, showing his father taking a younger Kingsley onto the mountain, where they regularly visited the cabin. His father was a mountaineer and traveler, and the cabin was a special place for him to share with his son. Now, Kingsley explains proudly, he can share the cabin with his father, when he comes to visit.

The job

While he believes that passersby have a right to take risks on the mountain, Kingsley sees his job as making sure they are informed of that risk. And the risk is substantial, he explains. Mt. Washington is only 1,917m but sees hurricane-force winds every three days, with windchill regularly reaching -34˚C. Mountaineers use it to train for attempts on places like Everest and Denali.

It’s essential that weather conditions on the mountain are measured and broadcast. Kingsley helps with that, too. Part of his caretaker duties involves measuring temperature and snowfall for the Parks Service.

It certainly is not a life most would choose. But this casual, intimate portrait of a caretaker challenges the assumptions one might have about people who choose to live in perceived deprivation. Kingsley is not your typical mountain hermit.

The Big Wait begins with an unending field of blue sky, then tilts down to show the dry, scrubby Australian landscape. As the shot lingers, a train, so far over the horizon that it's barely visible, slowly creeps into the frame. It's a perfect beginning to the short documentary, given its subject — two people and a dog, managing a tiny emergency runway and six cottages that almost nobody ever visits.

"Forrest is a township with one street, one intersection, and six cottages. And they're only here because we have an airport. And we have people to look after it. That's the managers, currently Greg and Kate," Greg and Kate Barrington say jointly in an interview.

In the snippet, they refer to themselves in the third person and finish each other's sentences — precisely as you'd expect people in their situation to do.

Population: two

"And Holly," they say, referring to their dog. "Population of Forrest is...two."

As Greg explains it, the cottages he and his wife caretake are hardly ever occupied because the "airport" he previously referred to is actually an emergency landing strip.

"Most of the time, it feels like an abandoned movie set because there aren't people," he says.

Nevertheless, Greg and Kate keep the cottages in pristine condition. They water and mow the lawns, wipe dust off the shelves, change the linens, place freshly rolled towels on the beds, and generally keep things ready for visitors. They even put fresh flowers in each of the rooms on a regular basis.

"You lose total track of time," Kate says over footage of the pair riding their bikes for exercise on the empty emergency runway. "I don't know what day of the week it is today. Or the date. It just...vanishes in a flash. The day is gone in a flash. Sunset, and next day, and you just keep rolling. And every day is different, that's the best part. So you rarely get bored," she continues.

That might seem hard to believe. But that's what makes The Big Wait such a fascinating piece of filmmaking. The viewer can't believe that Greg and Kate aren't bored, and yet they clearly aren't. They smile, they laugh, they fill their off hours with tennis games and haircuts. They drive their car at top speed down the runway, they ride their bikes, they have bonfires. They watch the sunrise and sunset.

So much space

"There's so much space, I find it gives me a chance to think more clearly," Greg says. "because the troubles really go away. There's nothing out there pressing in on you, and it's really what comes from inside. I suppose you throw away all the non-essentials. There's electricity, there's water. If the train comes through, there's food. With any luck a beer at the end of the day. And you don't have to worry about 'Am I going to get promoted,' because there are only the two of us out here to start with."

The filmmakers capture the experience with sensitivity. There's no question that Greg and Kate are a bit odd, and slightly awkward. But The Big Wait's tone is gentle, not mocking. And the film's cinematographer excels at juxtaposing the weirdness of that row of cottages with the beauty of the Australian landscape, particularly at dawn and dusk.

The Big Wait is the best kind of short documentary. It's sweet, inquisitive, and is over before it wears out its welcome. At only 14 minutes, you can fit it in on your lunch break while you consider your own promotion (or lack thereof). And you just might find yourself wondering if Greg and Kate are on to something.

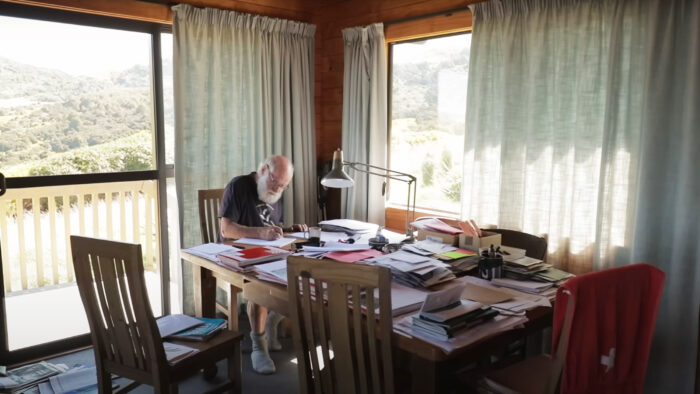

Hugh Wilson has spent the last 30 years regenerating native forest on New Zealand's Banks Peninsula. The story of how he did it is the subject of a lovely little 30-minute documentary called Fools and Dreamers: Regenerating a Native Forest. It's the perfect watch for anyone who needs their faith in humanity (and humanity's ability to fix its mistakes) restored.

With his unfailingly cheerful nature, white beard, bald head, glasses, and propensity for mixing long-sleeved flannel shirts with shorts, Wilson looks like a well-loved grandfather. But he's so much more than that.

Interested in plants from an early age, Wilson channeled his dual love of art and science into a thriving life as a botanist. He spent the first half of his career conducting detailed studies of the plant life on the Banks Peninsula — a region that used to be heavily forested but, by the late 1990s, was mostly farmland colonized by invasive plant life.

Starting from nothing

"Both Mauri and European settlements had a huge impact on the forest, so by 1900, less than one percent of the old-growth forest [on the Banks Peninsula] was left," he notes.

Then, an acquaintance asked if he'd be interested in running a private nature preserve. The goal? Bring tapped-out pasture back to the way it looked 800 years ago. And do it fast, because New Zealand had already permanently lost some of its native species of plants and animals.

"Some people say, well, why are you restoring the forest? It's kind of like asking why you should love your mother," Wilson says in the film. "We're totally, totally dependent on the vegetation and wildlife that supports our own lives."

So he hopped at the chance to manage the Hinewai Nature Reserve, a piece of land that would eventually cover 1,500 hectares. But there was some pushback.

Naive greenies?

"I am all for saving patches of bush, but the thought of starting from scratch on land that is clear enough to be used productively frankly appalls me. As for shutting up a whole valley, heaven help us from fools and dreamers!" one newspaper letter, written by a local farmer at the time, said.

"I think they basically thought we were naive greenies from the city. I'm sure they thought we'd come here with all these ideas, and within a year or two, we'd find out it was all just too hard, and it wasn't happening, and we'd [leave] again. Now here we are 31 years later. I looked at it as a great compliment because we need a few more fools and dreamers in the world," he notes.

The solution? Gorse, of course

The key to Wilson's plan was counterintuitive. The landscape he wanted to turn back into native forest had been used as pasture for generations and was also infested by gorse, an invasive flowering plant that grows quickly and renders pastures unusable. Many people thought he was nuts for not beginning his reforesting by trying to get rid of the gorse.

"Gorse is a terrible weed for pastoral farming. And no one, let alone me, would deny that. But nothing is black and white, is it? If you've got it, and it's kind of infested the landscape, then it's worth looking at its good points and saying, 'Well, maybe we don't have to fight it,'" he remembers. "We don't want pasture, we want the native forest to regenerate, and gorse is a wonderful nurse canopy for native forest regeneration."

This is why botanists are handy to have around. Wilson knew that gorse is a nitrogen fixer, meaning it fertilizes the soil it inhabits. It grows quickly and creates sheltered spots for shade-tolerant hardwood saplings to grow. But it has to have full sunlight to stay alive. So once native trees in the preserve sprout up beyond the gorse canopy, the invasive weed dies. It's a brilliant, elegant solution, and Wilson's spent the last three decades making it happen.

Wilson's routine

There are no motorized vehicles in the nature reserve, so Wilson begins each day with a walk to his current work site — a journey that sometimes takes him as much as two hours. He works all day and then treks back home. After dinner and a pipe, he turns to his management tasks, handling piles of the Hinewai Nature Reserve's paperwork late into the evening. Then he goes to bed, gets up, and does it all over again.

The result is spectacular. The once dry, grassy land in the reserve has largely returned to the lush forest it once was. Streams flow, even in the dry season, and there are 47 waterfalls on the property (that Wilson has found so far). And from the very beginning, the reserve has been open to the public.

"I think the community is now by and large in support of Hinewai," a local farmer says toward the end of the film. "We realized that the way farming was done over the years had to be changed. And I think what [Wilson] has done is helped people realize that it can be done. In a good way."

Mila Del La Rue comes by her free-riding chops honestly. Described as a skiing prodigy, the 18-year-old's father (Xavier) and uncle (Victor) are also big names in the free-ride snowboarding world.

Of a Lifetime is a 45-minute North Face film that chronicles the three as they venture to Antarctica in the company of a boat crew and mountain guide. The mission? Free-ride that continent's steep shorelines.

But first, they'll have to get there, a journey that requires five weeks on a small boat, with a notable journey through the Drake Passage. The famously treacherous stretch of water connects the Atlantic and Pacific oceans between the southern tip of Chile and the South Shetland Islands. The Antarctic Circumpolar Current blasts through the passage unchecked, and seas can top 12m. The resulting seasickness is not a great way to prepare for a ski excursion.

Mila spends most of the passage in a bunk, trying to hold down the last thing she drank, much to the amusement of her father. But in a theme that runs through the film, Mila is determined not to disappoint her accomplished family.

Bonding in Antarctica

"I'd like to go as far as them because I love skiing," she narrates.

For his part, Xavier sees the trip as a moment to grow closer to his family.

"Because of the age gap, Victor and I were always so far apart. Like living parallel lives. It's been forever since our last trip together, so now is the moment to finally reunite," he says.

In the first few days of the expedition, Xavier and Victor head off to tackle uber-steep lines with overhanging cornices while Mila gets the hang of ice axes and crampons under guide David's tutelage. But they don't call her a prodigy for nothing. Soon enough, Mila is ascending capably. But it's when she straps on skis and points herself downhill that the magic happens. She handles herself just like you'd expect — at first.

As the expedition continues, the lines get more intense for the Del La Rue family. Here Mila's youth comes into play again. Without the life experience of the older athletes, she freezes halfway down a steep run and breaks down into tears.

Blocked by fear

"I feel blocked by fear between crevasses, seracs, the rocks, and the ocean below. I keep imagining falling at any moment. I want to go back on the boat and feel secure. I doubt myself and my capabilities," she admits over tense action-cam footage of her shaky descent.

"I keep asking myself these questions," she continues. "Am I gonna feel this fear constantly? And I do have the [skill] level?"

For Xavier, the moment is a test of fatherhood. He's never seen his daughter freeze up like that. She's always been a fearless tagalong on his adventures.

"I wish I knew how to help her," he says as Mila grows increasingly short-tempered and withdrawn.

A little father-daughter heart-to-heart conducted Del La Rue style — which is to say at the top of a couloir after an exhausting ascent — does the trick. Xavier admonishes Mila for her fear-driven lack of communication, while Mila accuses her father of being too risky. Both agree to change their ways moving forward. The pair descend, whooping with joy.

Of a Lifetime is a classic ski film in many ways. Scenes of prep, scouting, and good times are punctuated by long, adrenaline-fueled skiing and riding sequences. The filmmaking team captures it all beautifully, making the best of the Antarctic backdrop and the Del La Rue family's easy charm.

A different family film

But at its heart, Of a Lifetime is a film about family, with all the connection, disagreement, and reconnection that concept contains.

"I've had plenty of time to think," Mila narrates in the film's closing moments. "And now I know what I really want. I want to learn to do things my own way. And I want to be strong. Because I didn't have this mindset before. So I want to say thank you, Dad. For bringing me on the trip of a lifetime. It sounds cliche, but I'll never forget it."