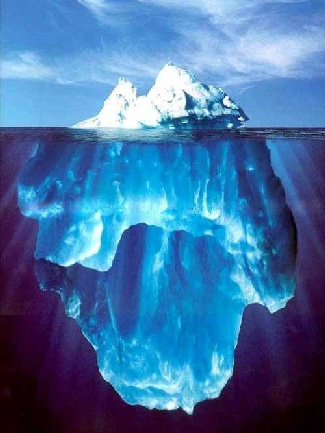

For Arctic residents and a few polar addicts, icebergs are familiar. I've skied, paddled, and boated past thousands of them. But most of us have just seen photos of these beautiful ice sculptures and may have only a vague idea where they come from. Here's a primer on one of nature's great art forms -- how they're made, how they differ from ice floes, and the many forms they come in.

Immobile icebergs

Arctic art

Icebergs vs ice floes

Multiyear ice: also not icebergs

A dangerous beauty

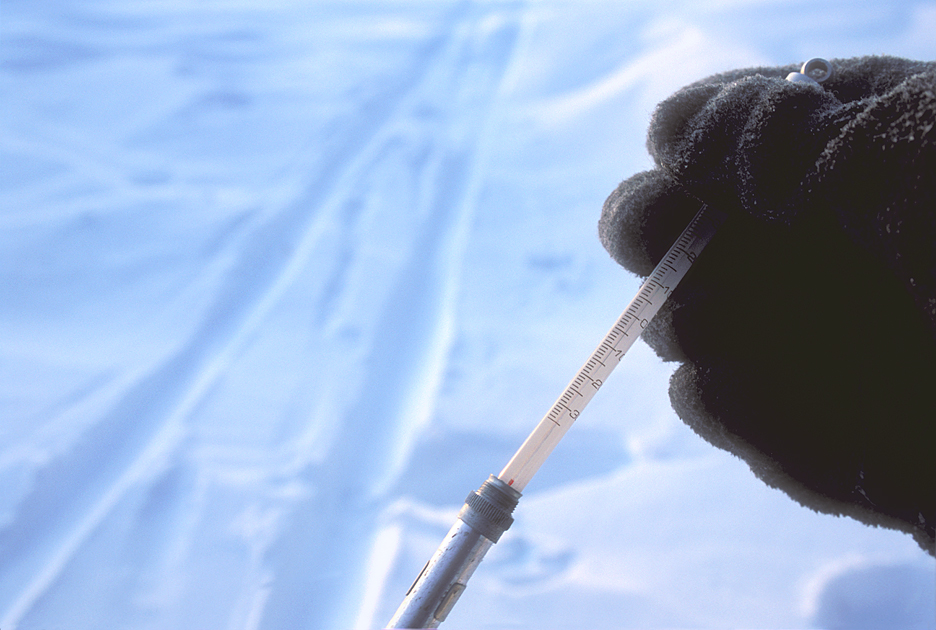

Icebergs can be as dangerous as they are beautiful. As a rule of thumb, boaters should not approach closer than twice the distance of an iceberg's height. See video below.

The second-largest country in the world, Canada has two million lakes, 8,500 rivers, and three gigantic coastlines. Most of the 40 million Canadians live within 150km of the U.S. border. Almost everything above that is wilderness.

Some of the 20 highlights below are classics, some are hidden gems, but all are guaranteed to deliver.

Eastern Seaboard

Day Trips

Balancing Rock

A local favorite worthy of national attention, Balancing Rock is a nine-meter-high basalt column poised above St. Mary’s Bay, Nova Scotia. Although the delicately perched rock looks as if a stiff wind would blow it over, it is not as precarious as it seems: Years ago, someone hooked a line over it and tried to topple it with a fishing boat, but thankfully failed.

Balancing Rock is located on Long Island, just a short ferry ride from Digby Neck. A 2.4km trail leads down to the photogenic pillar.

St. John’s puffins

A mere half hour south of Newfoundland’s capital, the Witless Bay Ecological Reserve holds North America’s largest colony of Atlantic puffins. A tour boat brings visitors close to the grassy island on which more than 260,000 pairs of the clown-faced birds breed. On the way to Witless Bay, don’t miss Cape Spear, the easternmost point in North America. Humpbacks and other whales often breach off the rocky point.

Fundy, New Brunswick tides

The world’s largest tides, as high as a four-storey building, flood the Bay of Fundy twice every day, submerging sea stacks, reversing waterfalls and seeming to cause rivers to flow upstream. Two lucky accidents make Fundy unique: As the bay constricts, it loses depth, so the tidal onrush pillows up. And the precise length of the bay, 290km, amplifies the waves even higher. It’s a trick of fluid mechanics called the Seiche effect, but it’s simpler to think of Fundy as a tuning fork pitched perfectly for high tides.

Adventure

Trans Labrador Highway

Adventurous motorists can now drive 1,200km through the wildest corner of eastern Canada, past ink-black lakes, lobsticks of black spruce and little else for hundreds of kilometers at a stretch.

The road begins in Wabush-Labrador City and deadends around Blanc Sablon, Quebec. From there, you must either retrace your way or take a ferry to Newfoundland.

The road is now fully paved, but so isolated that free satellite phones are available to borrow in case of breakdowns. (No cell coverage, except in some towns.) Sightings of black bears and wolves are common. One of Canada’s great wilderness roads. Note that Labrador accommodations tend to be basic motel/B&B.

Gros Morne National Park

As a drive, a day hike, or even a serious multi-day backpack, Gros Morne on the island of Newfoundland symbolizes eastern adventure at its best. The tangerine-colored tablelands are one of the only places to see the Earth’s mantle (usually 30km or more underground). The granite sugarloaf of Gros Morne Mountain makes a great all-day outing for strong hikers, while the Long Range Traverse is the Maritimes' premier backpacking trip. The three- to four-day trek begins with a boat ride to the end of Western Brook Pond, then a steep climb to one of the most iconic views in the country. And that’s just the beginning.

Gaspé

The Gaspé peninsula’s Route 132 follows the widening St. Lawrence River as far as famous Percé Rock. This arched monolith marks the final exclamation point of the ancient Appalachian Mountains, but it doesn’t signal the end of a Gaspé experience. You can head into the mountains themselves for an exquisite study in contrast -- great hiking during the day, luxury digs at night. ChicChocs Mountain Lodge lies in the heart of a nature reserve, at the end of a private road. Think fine dining, an outdoor hot tub, larch floors, custom birch furniture. Wall-to-wall windows look out onto two local giants, Mont Matawees and Mont Albert. Lucky hikers or skiers may glimpse Canada’s southernmost caribou near the open summits.

Culture

Lunenburg

Stroll past one of the Ferrari-red waterfront buildings or watch as a craftsman works on the latest incarnation of the famous Bluenose schooner, and you’ll understand why Lunenburg is one of only two urban UNESCO World Heritage Sites in Canada. (The other is Old Quebec.) Take in the Germanic architecture, or sample a more potent taste experience at a local distillery.

Covehead Harbour Lighthouse

Prince Edward Island has 54 lighthouses, but one of the prettiest is at Covehead Bay in PEI National Park. The red-and-white structure sits by itself on a grassy bench overlooking a swimming beach, surrounded by flowers, sand dunes, and rippling grass. On a dark day, the scene captures the windswept raw spirit of the Maritimes; in sunshine, it’s a postcard.

L’Anse aux Meadows

Driving distances in Newfoundland are farther than they appear, but if you have enough time on the island, don’t miss the World Heritage Site at L’Anse aux Meadows, at the tip of the Northern Peninsula, on the wind-lashed shores of the Atlantic Ocean. Here in 1960, researchers Helge and Anna Instad found the remains of the first (and still only) Norse village in North America.

Today, the original grassy mounds and depressions remain as subtle as most archaeological sites, but the exquisitely re-created longhouses, inhabited in summer by gregarious park employees chosen for their wild hair and dressed as Vikings, show how those explorers lived 1,000 years ago

Quebec’s Flavor Road

The Charlevoix region east of Quebec City already has great hiking, biking, and whale-watching, but it’s also become a gastronomical destination. The Flavor Road, concentrated around Baie-Saint-Paul, features artisanal cheeses, chocolates, breads, fine meats, and microbreweries to help wash those dainties down. Check www.routedesaveurs.com for details.

Westward Ho

Day Trips

Icefields Parkway

One of the world’s most beautiful roads, Alberta’s Icefields Parkway covers 230 mountainous kilometers from Jasper to the Trans Canada Highway just west of Lake Louise. En route, it scales three major passes. You could spend an entire summer traveling the Icefields Parkway and getting out whenever you saw a promising hike or photograph.

The extraordinary width of this well-maintained road allows you to park just about anywhere. You can whiz along at 90kph or Sunday drive at 40kph, carefully scanning the ditches for grizzly bears on early June mornings when dandelions draw the bears out.

The road boasts too many classic stops to list, but the not-to-be-missed category includes iconic Peyto Lake and the Columbia Icefields; and two great day hikes, Parker Ridge and Cavell Meadows, during the wildflower peak in mid-July.

Kananaskis Country

When locals in Calgary or Canmore want a day in the mountains, many head into Kananaskis Country. Its trails outshine many of those in the nearby national parks: they’re quieter, and since K-Country hikes start higher, they reach treeline sooner. More time in the alpine.

To get there, take Highway 20 south just east of where the Trans Canada Highway enters the Rockies, or opt for the rougher Smith-Dorien Highway up through the mountains behind Canmore. It eventually joins Highway 20, which soon climbs to 2,206m Highwood Pass –- the highest point in Canada along a paved highway. K-Country guidebooks list dozens of worthwhile hikes, but the drive to Highwood Pass itself is a gem.

Lussier Hot Spring

Canada has about 110 hot springs, all of them in the west or northwest. Some are closed to the public, others are giant paved swimming pools with piped-in spring water. But many are just natural depressions in a wild setting, known more to locals than to tourists. Lussier Hot Spring, in Whiteswan Lake Provincial Park north of Cranbrook in southeastern B.C., has that primitive feel.

The temperature of the pools ranges in summer from 34°C to 43°C. Go early in the morning, especially on weekends, if you want the place to yourself: It may not be on the international radar, but it’s popular with local families.

Waterton Lakes National Park

Grand old hotels abound in the Rockies but few are more spectacularly placed than the regal Prince of Wales Hotel. The 100-year-old castle sits on a giant berm overlooking Upper Waterton Lake. Here, you can enjoy high tea while peering out of giant floor-to-ceiling windows

If tea and crumpets sound too sedentary, tackle instead one of Canada’s best day hikes, the 20km Carthew-Alderson Trail. The one-way route requires parking in Waterton Village and taking a morning shuttle to the trailhead at Cameron Lake. A steady climb leads to eagle views at Carthew Summit, with glimpses into mountainous Montana. Then it’s down, down, down, past a chain of terraced ponds. In the distance, past a notch in the mountains, the hazy prairies begin, without the usual foothills.

Adventure

Dempster Highway

By the third week of August, a couple of hard frosts have killed the bugs, cranked up the vivid reds and yellows of the mosses, and transformed the Dempster Highway into one of the great scenic drives of the world. This 747km gravel highway begins just outside Dawson, in the Yukon, and finishes at Inuvik, on the Mackenzie River delta. You can drive the entire Dempster in a long day, but most people take two days, stopping at the lone station of Eagle Plains.

The Dempster crosses two mountain ranges, the Ogilvies in the south and the Richardson Mountains in the north. Day hiking into both ranges from the road is easy and requires little experience, except for knowing when to turn back. The road traverses the Ogilvies for some time, while it crosses the open Richardson Mountains at just one spectacular point.

Gwaii Haanas National Park

Canada’s Galapagos is also an iconic sailing and sea kayaking destination. Highlights include Burnaby Narrows, the richest intertidal area in the world. The narrow channel all but dries out at low tide, exposing thousands of colorful bat stars, sea urchins, red rock crabs, and a cornucopia of shallow-water creatures. The famous 200-year-old red cedar totems at SGang Gwaay bear witness to a time, not too long ago, when the powerful and artistic Haida ruled this part of the B.C. coast.

Lake O’Hara

Beloved by landscape photographers, the Lake O’Hara area in Yoho National Park had already captivated Group of Seven artists in the 1920s. The nearby Opabin Plateau remains a favorite with day hikers. To reach Lake O’Hara, take the morning shuttle (reserve your seat far in advance) from the parking lot near Field, B.C.

Although a campground and alpine hut cater to more hard-core outdoor people, many visitors either just stay the day or overnight at the swank Lake O’Hara Lodge. Prime season is the third week of September, when the larch have turned golden and the scenery with them.

Mount Robson

The highest mountain in the Canadian Rockies rises like a singleton volcano from the surrounding landscape rather than merely as the loftiest among many. Its massive, glaciated summit is best seen from Berg Lake. Small icebergs from a glacier drift in the lake’s turquoise waters. The three- to four-day B.C. backpacking adventure (20km one way) to Berg Lake puts you before one of the grandest scenes in Canada. More than a postcard, it could be the back of a hundred-dollar bill.

Those with the energy for a long day hike while camped at Berg Lake should tackle the nine kilometers to Snowbird Pass. The pass looks down onto the gigantic Reef Icefield. It’s like suddenly being transported to Antarctica. You have no idea that the icefield is there until the last moment, when you crest the final ridge and look down onto a white infinity.

Culture

Okanagan Wine Festival

Wine tourism is big business in B.C.’s Okanagan Valley, but nothing outdraws the wine festivals. Though the valley hums year-round with the appreciative ahhs of merlots and pinots being sampled, the pièce de résistance is the fall festival, which takes place in early October. You can take courses in wine appreciation, learn how to pair wine and food or simply show up at one of the region’s 60 wineries and cart away a case of your favorite vintage. www.thewinefestivals.com

Canmore Folk Festival

A folk festival with top talent, a community feel, in a gorgeous setting: It’s hard to imagine finding all three in the same place, but that’s what happens every summer in this Rockies town on the border of Banff National Park. Old folkies share the intimate stages with rising stars on the world music scene, while greying hippies sway to the beat and music lovers of all ages gorge on great local food. The non-alcoholic festival is especially family-friendly.

As we reported yesterday, a polar bear attacked a skier in Auyuittuq National Park on Baffin Island last week. Details are scant, but the skier was evidently injured but all right. Authorities later shot the bear.

Several of our readers commented on the incident. "It amazes me how people can be so lacking in common sense," wrote someone who identified as Jennifer. "You are trespassing on the polar bear's home, yet you blame them when you're attacked... If you stay away from them in the first place, you would not be attacked. It's simple, stay out of their habitat."

"Why would anyone kill the bear??" said Andrew. "He's living in his habitat, and people are invading it. Terrible!!!"

"With polar bears now endangered and their habitat rapidly shrinking through no fault of their own, this isn't really acceptable," agreed MW.

Not the bear's fault

A similar article in Baffin Island's own Nunatsiaq News also drew several comments. Note that not all readers of this Arctic newspaper are Inuit, or even live in the north.

"This was 100 percent not the bear's fault, as it was obviously not a predatory attack," wrote Terry Sigurdson. "The bear was most likely protecting cubs or startled...Sad ending to a preventable situation."

"If you’re stupid enough to go into bear or other wildlife country to ski or whatever when you are only concerned about having fun, you deserve whatever wildlife does to you," said another.

No firearms?

Finally, two readers took issue with Parks Canada's rule, mentioned in the Nunatsiaq News story, that non-Inuit are not allowed to carry firearms in Arctic national parks.

"This is wrong in so many ways," said one. "Baffin Island is not Banff. This polar bear attack is 100% the fault of Parks Canada and their crazy rules."

"I completely agree," said another. "They should be held liable for any polar bear attacks. It’s crazy to think that in Svalbard, they don’t allow people to step into polar bear territory without a gun, and here they’re forcing hikers to expose themselves to danger by not carrying one."

There's a lot to unpack here. Let's try.

I may be the editor of ExplorersWeb, but I'm also an Arctic traveler who has had over a dozen close calls with polar bears. I've never had to kill one, but it's been close -- for both of us. So my perspective will be affected by my experiences and by the fact that I've chosen to travel the Arctic independently in the first place.

I do carry a firearm, and although I once went without one in an Arctic park where polar bears were historically rare, it was an uncomfortable gamble. Polar bears are great explorers and can show up anywhere, anytime. A tour group discovered this about 20 years ago, when a polar bear nosed around their camp on northern Ellesmere Island -- in a spot where polar bears had never been seen before.

Vulnerable vs endangered

A few small corrections of the readers' comments:

- Polar bears are not endangered, they're vulnerable -- a still-concerning but less dire classification. Some populations, such as the one in western Hudson Bay, are more affected by climate change than others. Other populations are doing well. There are more polar bears off the coast of northern Labrador than there have ever been in historic memory.

- It is certainly not obvious, especially given the paucity of details, whether the incident in Auyuittuq last week was or wasn't a predatory attack. Humans are very different from a polar bear's usual prey, which is seals. Most polar bears want nothing to do with us. They run away, or amble off in that dignified bear manner. Polar bears are, however, one of the two animals in North America that occasionally stalk people as food. (The other is the cougar.) Typically, an interested polar bear approaches slowly, trying to make up its mind about you. "Is this something that might injure me, or should I make a play for it?" Adolescent males -- cocky like human adolescents, still poor seal hunters -- are the worst offenders; almost all my incidents have been with them. However, as Russian polar bear biologist Nikita Ovsyanikov once explained to me, polar bears are among the world's most conservative animals. Ovsyanikov became famous for walking around polar bears with just a long stick and an attitude. With an confident attitude (feigned, of course), they are relatively easy to scare away with non-lethal deterrents like flares or bear spray. A warning shot sometimes works too, though not always. But while it is not possible to say anything about the incident on Baffin Island, I would not classify most of my close calls with polar bears as "predatory attacks." Mostly, they feel as if the polar bear is probing, to see if an escalation is justified.

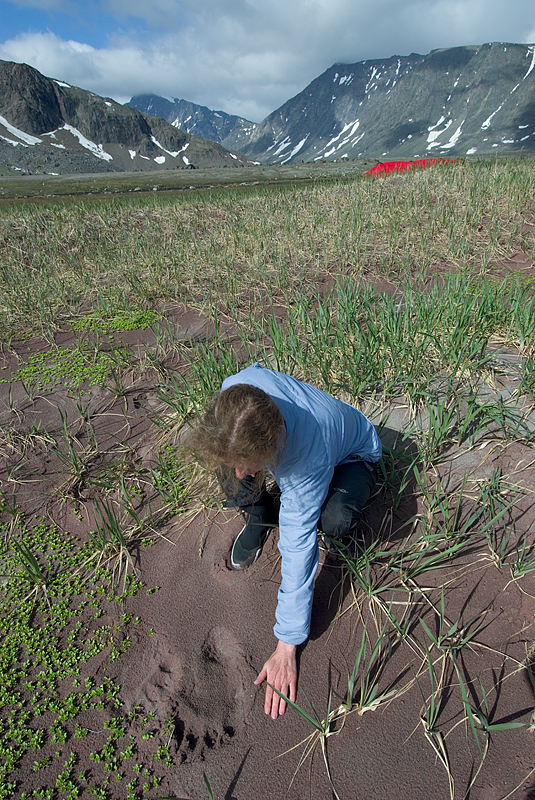

A polar bear patrolling a beach detoured to investigate a campsite in northern Labrador. Photo: Jerry Kobalenko Cubs not an issue

- Nor is it likely that the polar bear was "protecting its cubs." That's a potential issue with black bears and grizzlies surprised in the confined spaces of the southern woods. In the open Arctic, both parties tend to see each other coming, and a polar bear simply moves off.

Photo: Jerry Kobalenko - As one reader of Nunatsiaq News pointed out, authorities killed the bear not as capital punishment for the crime of injuring a person, but because such an encounter can lessen a bear's fear of people and lead to other, more deadly incidents. Down south or up north, this is pretty standard wildlife management following any animal-human clash. It's one reason why responsible outdoor people need to take pains to avoid these in the first place -- eg. by not feeding wildlife. The person may survive, but the animal is certainly doomed.

- Finally, it is a common misconception that anyone who goes out on the land in Svalbard, those polar bear-rich Arctic islands off the coast of Norway, must carry a firearm. That was never the case; it was just strongly recommended. In recent years, it's become a little more time-consuming for foreigners to acquire a firearm permit.

For 'fun'

Some have criticized the skier for being up there at all, potentially risking the life of a polar bear for "fun." The implication is that nature is great, but only without people. We inevitably gum up the works, so we should stay in our cities and leave the animals safe and unmolested in their shrinking domain. One can disagree with that, but it's impossible to argue against it, because it's essentially a religious position.

There have been a couple of cases in the Canadian Arctic where adventurers behaved badly and caused the death of a polar bear. Years ago, a Swiss man named Markus Bischoff let a bear come too close during a solo dogsledding adventure so he could get better photos. The bear may then have come too close, and Bischoff shot the bear. He was later charged.

A photographer in Churchill, Manitoba, who was not paying attention, was chased around his truck by a polar bear. Another photographer filmed the close call. The man managed to take refuge in his vehicle.

Minimize risk

There are many ways to minimize the risks of a polar bear encounter that can go badly for one or both parties. However, if you travel the Arctic enough, you will eventually see polar bears, and almost certainly have to deal with a too-curious one. You can't go into polar bear country with the woo-woo attitude that Timothy Treadwell had with his grizzlies in Alaska. You have to be prepared to defend yourself -- while at the same time, recognizing what a failure shooting a polar bear would be, and to do everything possible to avoid it.

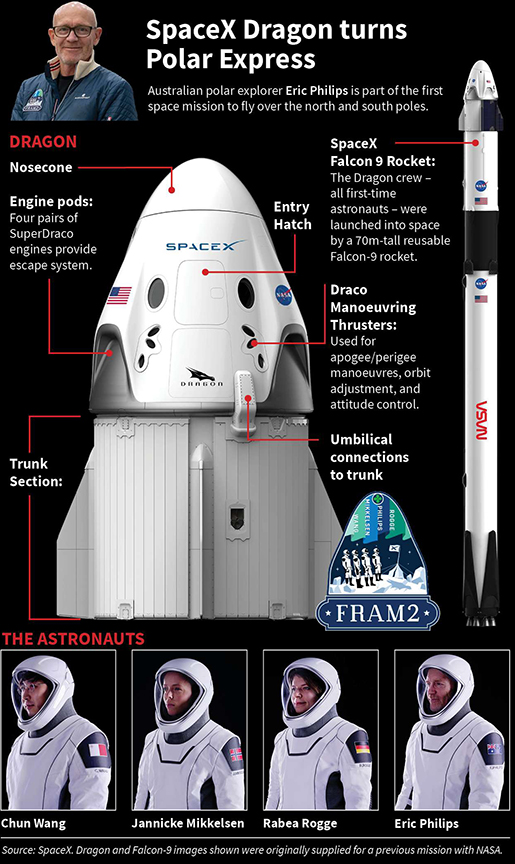

For three and a half days earlier this month, Eric Philips, 62, was in an environment that made his familiar Antarctic plateau seem almost hospitable. Sardined in a tiny capsule with three other amateur astronauts, he orbited our blue marble at 7.6km/sec. Outside, the blackness of space, with its microgravity and zero air and unseen perils of radiation and micrometeorites.

"What never gets old is Zero G," Philips told ExplorersWeb. "It's like being a child all over again."

Previously, we explained how Philips' late-career adventure came about. Two years ago, he guided a ski tour on the Norwegian Arctic Islands of Svalbard. One of his clients, Chinese-born Maltese citizen Chun Wang, was interested in talking about space travel. Not uncommon: Simple environments often appeal to polar types.

But in this case, Chun had the resources to do more than talk. He had made a fortune in bitcoin mining and wanted to buy a commercial flight on SpaceX. A few months later, he invited Philips, Rabea Rogge (a German robotics engineer and fellow skier on the tour), and cinematographer Jannicke Mikkelsen, based in Longyearbyen on Svalbard, to join him. Chun would cover expenses, in the range of $200 million.

A year of training

For a year, Philips and his three partners trained for the mission, which they dubbed Fram2 after the famous Norwegian polar ship. Most of the training took place at SpaceX's headquarters in Los Angeles. The Dragon capsule flew on its own, but they had to learn what to do in case something went wrong. Among the things Philips had to practice as the designated medical officer was inserting a catheter in case of an emergency. However, all went well.

"In the end, we used maybe one percent of our training," said Philips.

On March 31, after several days in quarantine near Cape Canaveral in Florida to avoid catching a bug before the flight, it was time to launch.

Centrifuge training had given some practice with the tremendous G-forces of a rocket tearing itself free of Earth's gravity, but even that didn't compare to the 4.6 Gs of the real thing. It was enough for them to feel their organs compress, said Philips. But it didn't last long.

Kármán line

They cleared what is called the Kármán line, 100km above the Earth, at which point they were officially astronauts. Soon, the main engine expended its propellant and fell away. Almost immediately, the second engine kicked in, propelling them to an altitude of 200km. From there, onboard thrusters lifted the capsule into orbit, some 450km above the Earth.

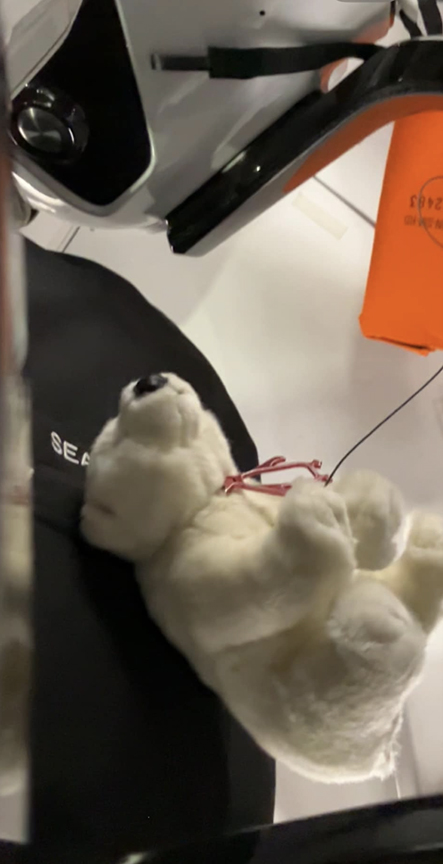

The first sign of microgravity Philips noticed was the loose ends of his restraint straps beginning to float. At the same time, a mascot that astronauts call the Zero G Indicator began to float around the 2.5-meter-wide capsule. For this mission, their Zero G Indicator was a stuffed polar bear wearing an emperor penguin necklace.

This wasn't just a nod to Philips' background or where they met. This was the first time a spacecraft was planned to orbit the Earth via the Poles. From the 1957 launch of Sputnik until now, they have all been, from our perspective, "horizontal" orbits, not vertical.

"Because of our polar orbit, the Earth rotated beneath us, so we passed over every part of it," Philips told ExplorersWeb. "We're told this is a blue planet, because of all the oceans. But we were often over whiteness."

Pure silence

In orbit, Philips noticed how quiet it was. Freed from gravity and without the friction of the atmosphere to slow them, they flew (or rather, fell) around the Earth with only occasional need for the booster to kick in, to keep their orbit from deteriorating. When it fired, sparks appeared outside the window, like a little fireworks show.

SpaceX broadcast the launch on its website, and a program called Zero Six Zero showed the Earth in more or less real time, with a simulated version of the capsule moving above it. In almost no time, they made their first pass over the South Pole. Forty-five minutes later, they flew over the North Pole. Orbiting at 27,000kph, it took them just three-quarters of an hour to travel halfway around the world.

Every day, they went through multiple phases of darkness and light. They made 55 orbits in all. Always, Philips delighted in "the sheer joy of microgravity."

"What surprised me is how quickly I adapted," said Philips. "I'm sensitive to motion sickness, and I was likely to get terribly space sick. But the first day was great. On the second day, we all experienced a little nausea but quickly recovered."

A warm capsule

The interior temperature of the capsule ranged from 24˚ to 28˚C -- warm for polar travelers. When they needed to sleep, they climbed into thin sleeping bags and just floated around above their seats, bumping lightly into one another as they slept.

During the day, drifting around in the cramped space, they were often "a tangle of limbs," said Philips. His experience of being stuck in a small tent in Antarctic blizzards for three or four days at a time came in handy here.

Besides the otherworldly sensation of microgravity, everyone's favorite experience was their time in the Plexiglas cupola — a clear dome atop the capsule, just big enough for one person at a time. From there, they could take turns looking at both the blackness of space and our amazing planet below. The Plexiglas was solid enough to repel radiation and any micrometeorites that might strike it. During launch and splashdown, a protective nosecone covers the cupola.

Philips knew from his prior reading that, contrary to the old myth, the Great Wall of China is not visible from space -- and sure enough, it isn't. But he did notice at night how bright China was with artificial lights, "far more than any other country."

What he saw

He also identified other areas, both natural and manmade: their launch site at Cape Canaveral, the mountains of Alaska, and Svalbard, the archipelago that brought them all together. Philips also made out parts of Queen Maud Land in Antarctica, although at this time of year, darkness or twilight had settled over much of the White Continent.

The crew had 11 large satchels tucked away in a cargo section, containing food and water for five days. "It was like packing a sled," recalled Philips. The Australian was even able to enjoy coffee in space, although it probably didn't measure up to the typically excellent coffee in his own country.

For unclear reasons, SpaceX has always been shy about its onboard toilet facilities, and Philips and the others had to sign an NDA not to discuss it. Some space aficionados have pieced together information about it, however. Philips admitted that on such a short-duration flight, astronauts are administered enemas before launch to simplify the first couple of days.

700 astronauts

Since Yuri Gagarin, there have been almost 700 astronauts, but counting these four, there have only been 11 tourists who have gone beyond suborbital experiences and into outer space. As part of their program, they performed some 22 experiments, including taking the first X-ray in space and growing mushrooms. Cinematographer Jannicke Mikkelsen filmed. But largely, it was about soaking up an out-of-the-world experience.

When it came time to descend, they packed everything away -- including the Zero G Indicator -- put on their suits and strapped themselves in. "It was like being in a sailboat and preparing for an impending storm," said Philips. "You do your best to prevent items from flying around."

Their reentry also generated 4.6 Gs, but their brief time in weightlessness made it feel even more forceful than during the launch. Meanwhile, the temperature outside the capsule rose to 2,000˚C from friction in the atmosphere.

Two drogue parachutes deployed at about 5,500m in altitude while Dragon was moving at approximately 560kph. At about 1,800m, the drogues pulled out the four main parachutes. The Dragon hit the water at about 25kph off Oceanside, California -- the Dragon's first Pacific splashdown.

A ship waiting five kilometers away then came and winched the capsule on board. All the astronauts were able to exit the hatch by themselves, although one was a little shaky walking to the medical bay.

'A hurricane raged in my mind'

But after such an intense, at times ecstatic experience -- microgravity, seeing our planet for the first time from space -- there was bound to be a hangover. Philips recalled:

At the medical bay, my body went into shutdown. It was difficult to communicate with people in any meaningful way. A hurricane was raging in my mind. I could answer questions like, 'Are you in pain?' with no problem, but for two or three days, I couldn't describe the experience.

Days later, they still experienced floating sensations. Once at breakfast, Philips imagined he could float over to the buffet to get his food.

While their extraterrestrial experience made some past astronauts a little "spacey" in their afterlife on Earth, Philips isn't concerned.

"I'll remain the staunch skeptic I've always been," he says.

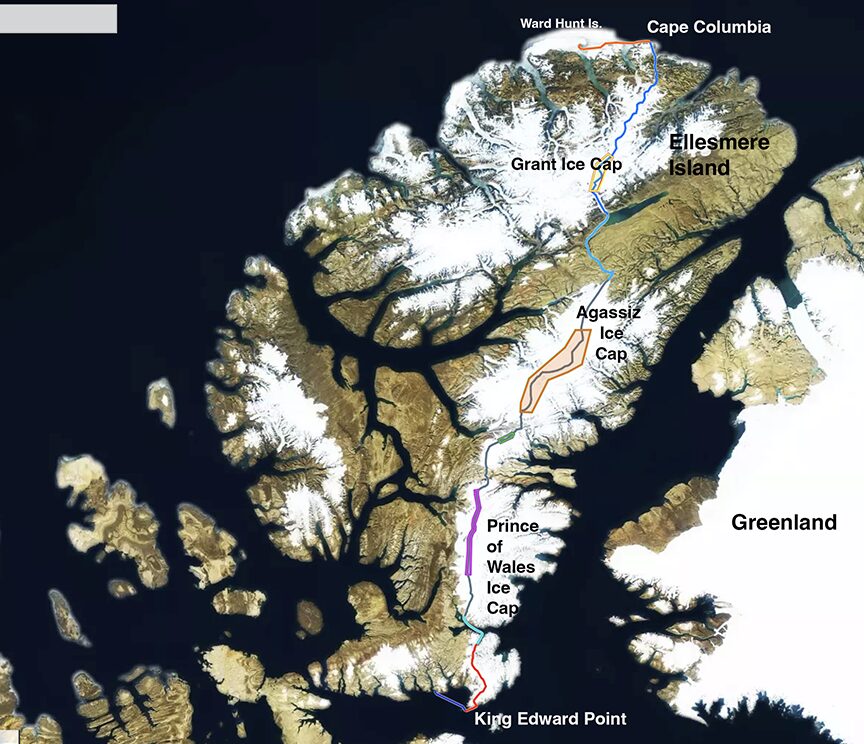

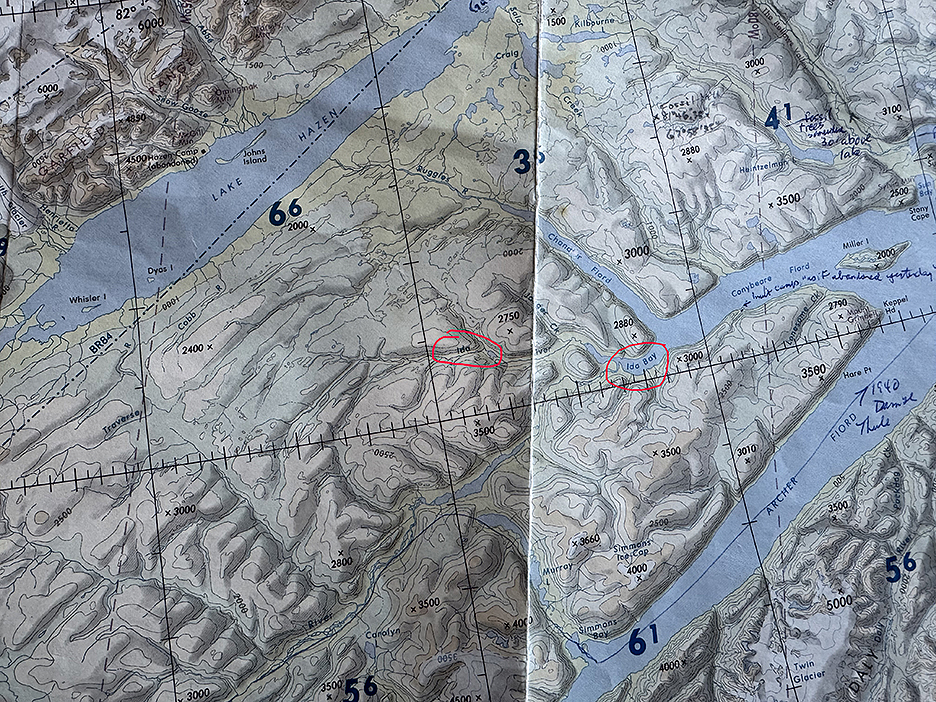

In less than a week, Norway's Borge Ousland and France's Vincent Colliard will fly north to Resolute Bay, Canada. There, they'll take a $72,000 charter flight (ouch) to the north end of Ellesmere Island. For the next six or seven weeks, they'll ski south over the interior ice caps to King Edward Point, the southernmost tip of Ellesmere.

It's part of Ice Legacy, their multi-year project to cross the world's 20 largest ice caps. And except for the solo crossing of Antarctica that Ousland, now 62, did back in 1996-97, it will be their longest. The 1,100km will tick off three ice caps on their list -- the Grant, the Agassiz, and the Prince of Wales. They will then have only four left to do.

As a side project, the pair will attempt to make the first unsupported north-south crossing of Ellesmere, the tenth-largest island in the world. Two other parties did a vertical traverse of Ellesmere -- John Dunn and three partners in 1990 and Bernard Voyer and team in 1992. Jon Turk and Erik Boomer skied/kayaked completely around the island in 2011, passing both the northernmost and southernmost points. But all three of these previous expeditions had multiple resupplies. Ousland and Colliard will carry everything with them.

Cape Columbia

The Twin Otter aircraft will land them at Ward Hunt Island, a small satellite off Ellesmere's north coast. They will ski east to Cape Columbia, Ellesmere's (and North America's) northernmost point. At 83˚07', it is just 760km from the North Pole. The veteran Ousland has touched Ward Hunt Island before, when he and Erling Kagge became the first to ski unsupported to the North Pole from Ellesmere in 1990.

Their route includes brief land sections between the three ice caps, but they will travel mostly on glacier ice. They'll largely ski under their own power but will carry Beringer ski sails to take occasional advantage of the light Ellesmere winds. Ski sails are more rudimentary than kites and do not need beefy mountaineering skis and boots, like kiting does. You can ski sail and manhaul with the same gear, Ousland told ExplorersWeb.

Veteran duo

Ousland's many accomplishments in both the Arctic and Antarctic put him at the very head of modern polar travelers. Besides his unsupported North Pole trek with Kagge, he skied solo and unsupported to the North Pole from Russia in 1994 and became the first person to cross Antarctica (also ski sailing) in 1996-7. In 2006, he and Mike Horn skied to the North Pole in winter, and in 2019, he and Horn crossed much of the frozen Arctic Ocean, also in the dark. The two were dropped off and picked up by ship.

Although Colliard, 39, can't match such an unprecedented polar resumé, the pair have completed 10 of the 13 ice caps together. (Ousland did Antarctica, Greenland, and Iceland on his own.) Last year, Colliard broke Christian Eide's long-standing speed record from Hercules Inlet to the South Pole, covering 1,130km in 22 days, 6 hours, and 8 minutes.

North to Nowhere is the funniest film about North Pole expeditions that you'll ever see. Polar explorers have always taken themselves very seriously, but luckily Montreal filmmaker Josh Freed took a bemused perspective on the crazy cast of characters vying to reach the top of the world one spring back in the late 1980s.

At that time, modern North Pole expeditions were in their heyday. In 1986, American Will Steger and his party made the first unsupported dogsled trip to the Pole. That same year, Jean-Louis Etienne of France skied the 760km alone. (Earlier, in 1978, the great Japanese adventurer Naomi Uemura had reached it alone using dogs.)

These were serious adventurers, but every year, several less prepared travelers also showed up in Resolute Bay, Canada, touting their great plans to reach the North Pole in various creative ways. Resolute's beloved outfitter, Bezal Jesudason -- featured in the film -- provided logistics and tried to advise them as best he could. Jesudason, who improbably came to the High Arctic from India, used to joke that he himself was planning an expedition to the North Pole by elephant.

Do you need oxygen?

In this pre-internet era, information about the North Pole was not as easy to come by as it is today. Some would-be polar explorers would phone to ask if they needed to bring oxygen "that high up." One British man imagined that he could walk about 80km a day over the broken surface of the Arctic Ocean and was going to show up with just 10 days' food to reach the North Pole. "He was even so generous as to bring two days' extra for bad weather," Jesudason later told me. Luckily, the outfitter managed to dissuade the man from coming.

Scandinavians were usually competent, but one spring, two older Swedes showed up in Resolute with no idea how to use a camp stove. Unable to melt water during two brief shakedown trips near Resolute, the experience so humbled them that they went home without even beginning their expedition. Others spent thousands of dollars to charter an aircraft to the north end of Ellesmere Island to begin but quickly realized they were in over their heads. Typically, they called for a pickup a few days later, citing back injuries as a convenient excuse for quitting.

An influencer ahead of his time

The expeditions profiled in North to Nowhere belong to this zanier crowd. Two French pilots/gourmet chefs set out to fly their canary-colored ultralight plane to the North Pole. There was Shinji Kazama, a Japanese Yamaha salesman who -- heavily supported by Inuit with dogsleds -- took his motorcycle to the Pole. Then there was Dick Smith, the founder of Australian Geographic magazine, who sought to go there in his helicopter. The extroverted Smith was a visionary who anticipated the selfie/Instagram generation and walked around holding a lightweight movie camera pointed at himself and breathlessly narrating the adventure that was about to unfold.

With admirable restraint, North to Nowhere documents the goings-on during this brief Golden Age of what people in Resolute used to call the Silly Season.

Climate change, politics, and difficulties chartering aircraft have ended the hijinx for the time being. The last full-length North Pole expedition was in 2014.

The official "10, 9, 8..." countdown has not quite begun, but later this morning, at 9:46 am ET, Australian polar guide Eric Philips and his three fellow astronauts will blast off into space from Florida's Cape Canaveral aboard SpaceX's Falcon 9 rocket. For the next three-and-a-half days, they will orbit the Earth via the North and South Poles -- an orbital track never done before.

For the 62-year-old Philips, this late-career opportunity came out of the blue. He was guiding a ski tour on Svalbard. One of the participants, Chun Wang, was interested in talking about space. It turned out that Wang had made a fortune in the early years of bitcoin mining and wanted to buy a commercial space flight from SpaceX. He invited Philips to join him, along with two other Svalbard acquaintances, Rabea Rogge and Jannicke Mikkelsen. The cost of the flight is undisclosed, but previous private missions on SpaceX cost around $200 million.

The four of them have been training at SpaceX headquarters near Los Angeles for the past several months. Now, weather permitting, the big day has arrived.

Among their many new experiences, Philips, who wears glasses, has learned to wear contacts for the first time so his glasses won't fog up inside the space suit. However, sometimes myopia temporarily clears up in zero gravity, so he might find that he no longer needs them -- at least for those three-and-a-half days.

You can watch the launch live and follow what they call the Fram2 mission, named after the famous Norwegian polar ship, here.

Today, a naval warship rescued 44-year-old ocean rower Aurimas Mockus off the coast of Australia.

The Lithuanian rower was within a week of completing his 12,000km row across the Pacific from San Diego to Brisbane when Tropical Cyclone Alfred hit him. It generated winds up to 100kph and waves up to seven meters high. He set off a distress signal on Friday when he was about 740km from his endpoint.

Australian search-and-rescue authorities sent out planes, which eventually located the exhausted rower. A naval ship, HMAS Choules, was dispatched to pick him up.

Mockus had been rowing on his own for almost five months.

Only three rowers -- Peter Bird, John Beede, and Michelle Lee -- have completed the Pacific crossing.

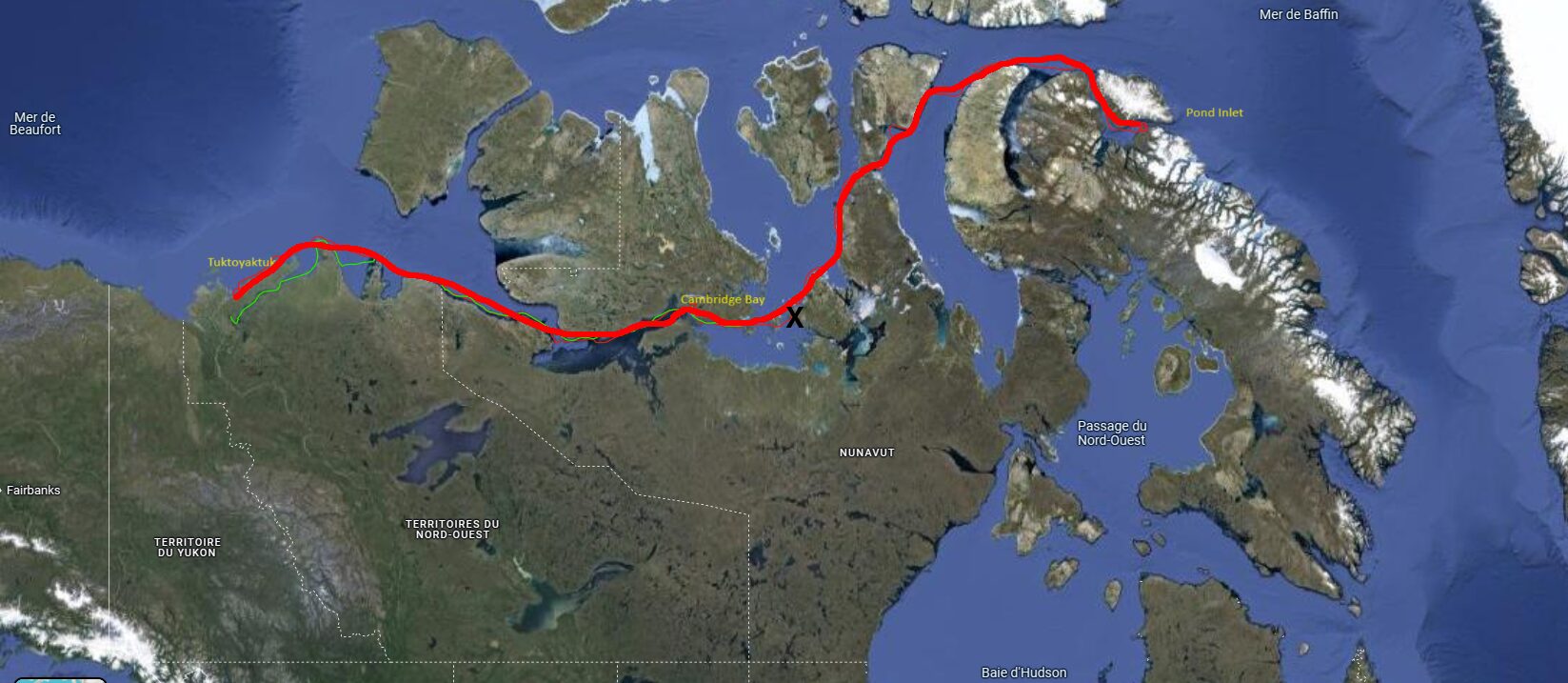

In 1905, during Roald Amundsen's first transit of the Northwest Passage, two of his men set out from Gjoa Haven to explore the unmapped east coast of Victoria Island. They reached halfway up before turning back due to the lateness of the season. Now 38-year-old Anders Brenna of Oslo will set out early this spring to manhaul 1,100km alone from Gjoa Haven all the way up past the explorers' farthest north and around to Glenelg Bay on northern Victoria Island.

Brenna, a father of two, seems in some ways a typical Norwegian, with a practical attitude and a background in winter activity that could make up for his modest arctic experience. His parents worked in search and rescue, and he spent a lot of time outdoors as a kid. He did cross-country skiing and biathlon in his teens and trained in winter with the Norwegian military. (He's still employed as a civilian with the military.)

Then in 2022, the arctic bug bit him. He did a 120km solo ski trip in Hardangervidda, a subarctic national park between Bergen and Oslo. There, he traveled 120km in a week between Finse and Haukeliseter. He had already traveled Hardangervidda with the military, but Brenna wanted to do this on his own, to begin to develop the routines of independent arctic travel.

A big step up

As a next step, last April, he joined a 20-day expedition in the Canadian Arctic run by Borge Ousland's adventure company. He and half a dozen others skied 400km from Cambridge Bay to Gjoa Haven in Nunavut. When he was at the airport in Gjoa Haven to fly home, he realized he wanted to return. He's been planning this current endeavor ever since.

Brenna acknowledges this will be much harder than Hardangervidda and a guided three-week tour. He'll have to navigate, ski an average of 20km a day with a much heavier sled, deal with severe cold, camp totally on his own, and watch out for polar bears.

"This is another league from what I've done before," Brenna admits, "but that's not a reason not to do it."

Along with expedition logistics, he has been researching the 1905 expedition of Godfred Hansen, Amundsen's second in command, and engineer Peder Ristvedt. The pair dogsledded from Gjoa Haven across the sea ice and up the east coast of Victoria Island. Although Amundsen became the first to sail through the Northwest Passage, this was the only new land his expedition explored.

Cairn search

Hansen and Ristvedt turned back at what they called Cape Crown Prince Olaf, where they built a cairn that Brenna hopes to rediscover. There, they sighted a distant cape to the north that they called Cape Nansen, after the great Norwegian explorer. Brenna is particularly looking forward to standing at Cape Crown Prince Olaf and figuring out exactly what they meant by Cape Nansen.

He will then continue north along Victoria Island, covering the unexplored area they missed, which explorer Vilhjalmur Stefansson first mapped on his Canadian Arctic Expedition 10 years later.

Interestingly, in 1919-20, Godfred Hansen made another journey on behalf of Amundsen. Amundsen hoped to succeed where Nansen's original Fram expedition had failed and sail his ship, now the Maud, across the Arctic Ocean via the North Pole. To this end, he had Hansen travel the north coast of Ellesmere Island and leave supply depots for him. Hansen's distinctive russet-colored tins stenciled with "Beauvais Kjobenhavn" (the Danish company providing the food) still lie in obscure caches on northern Ellesmere Island. Amundsen's expedition never came off.

A cold start

Since Brenna can't afford a helicopter pickup from his endpoint on northern Victoria Island, he is leaving early -- in mid-March, the coldest time of year -- so that an Inuit man can snowmobile overland from Cambridge Bay to pick him up while there is still enough snow coverage. Brenna estimates that the journey will take between 50 and 60 days.

"I'm not going in March to make things worse for myself," says Brenna.

Indeed, he believes in trying to make these journeys as comfortable as possible.

"It's easier to stay outside a long time if you're comfortable," he says. "It's also about developing routines to conserve energy."

Brenna admits he's a bit "old school" and will post the occasional entry on his website during the expedition, but don't expect a daily Instagram update.

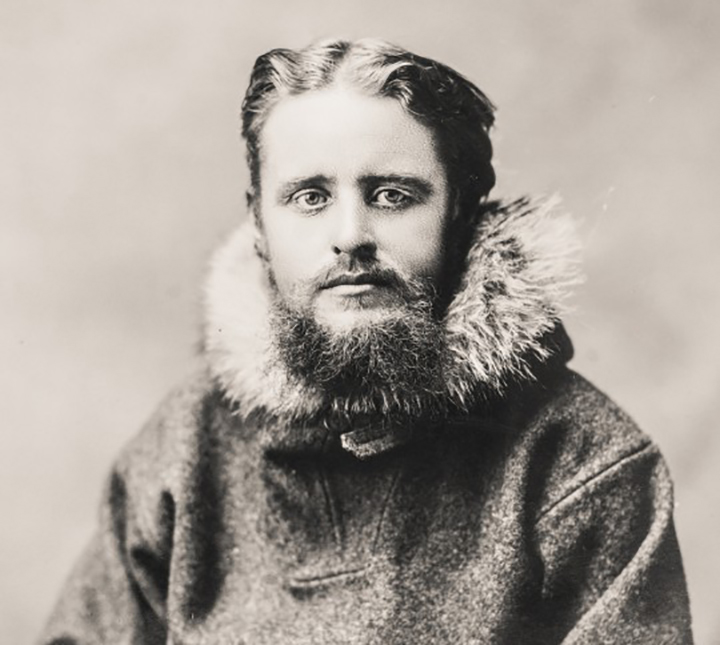

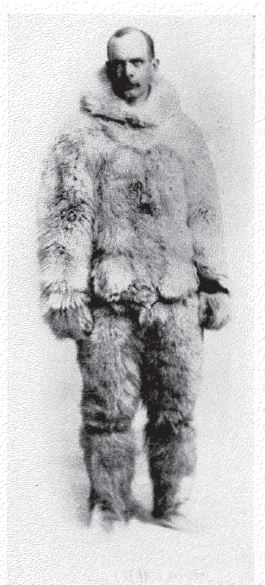

So far, the three High Arctic deaths we've covered in this series have all been the certain result of foul play. Charles Francis Hall's death is more mysterious. It may have been a murder whose motive combined expedition friction and a love triangle. Or maybe not.

Hall's background as an arctic explorer was unusual. He grew up in New Hampshire with little education, became an apprentice blacksmith in his teens before moving to Cincinnati. Here, he somehow became a businessman and newspaper publisher. He only became interested in the Arctic in his late 30s, drawn in like many others by the mystery of what happened to John Franklin and his crew.

In 1860, at the age of 39, Hall went north for the first time as a passenger on a whaling ship. Although they didn't reach the area where Franklin disappeared, Hall turned the voyage into an exploration. They showed that "Frobisher Strait" on southern Baffin Island was really just a bay and brought back some artifacts from Frobisher's expedition.

A remarkable couple

He also met a remarkable Inuit couple who spoke English, Ipirvik and Taqulittuq. Historically known as Joe and Hannah, they became prominent guides for several white explorers and accompanied Hall on all three of his expeditions.

His second expedition began in 1864. This time, he reached King William Island in the central High Arctic, where Franklin's ships became trapped in the ice and where so many men perished. He made no great discoveries but did find some bones and other remains from the lost expedition.

Hall stayed north for several years, learning from Inuit like Ipirvik and Taqulittuq how to live in the Arctic. Unlike many famous explorers who went north merely as a career move, Hall genuinely loved the place.

“The Arctic is my home," he wrote once. "I love it dearly; its storms, its winds, its glaciers, its icebergs; and when I am there among them, it seems as if I were in an earthly heaven or a heavenly earth.”

Hall's attraction to the Arctic and curiosity to learn made him an excellent independent traveler. He was also undoubtedly a good self-promoter. He came out of nowhere, and through interest, vigor, and self-marketing, turned himself into one of the foremost American arctic explorers of his time.

Not a leader

But as a leader of men, he was poor at commanding loyalty. In 1868, still on that second expedition, he shot and killed a crew member under questionable circumstances. Hall later claimed the man was attempting mutiny, but other whalers on the ship said the murder was more frivolous. Nevertheless, Hall was never prosecuted.

On his return to the United States, the former blacksmith's apprentice found himself in lofty circles. U.S. President Ulysses Grant and members of Congress secured for Hall a $50,000 grant -- about $1.3 million in today's dollars -- to lead an expedition to the North Pole. In 1871, Hall, an old whaling captain named Sidney Budington, who also captained the whaler on Hall's first expedition, and many others set out for North West Greenland aboard a ship called the Polaris.

The expedition featured even more drama and conflict than usual. Hall was the leader but was not the ship's captain. Some of the crew -- particularly a troublesome German contingent -- resented his authority. Factions on the ship made the atmosphere tense.

Nevertheless, it was a good ice year -- one of several in the last quarter of the 19th century -- and the Polaris forged north between Canada and Greenland as far north as 82˚11', the highest latitude a ship had ever reached. There, pack ice forced them to retreat about 50km to 81˚37' on the Greenland side. They found refuge for the winter in a sheltered nook called Thank God Harbor.

A mysterious death

In October -- by which time the sun had already set for the winter at that latitude -- Hall dogsledded north for two weeks on a brief exploratory mission toward the North Pole. When he returned, he became violently ill after drinking a cup of coffee. The ship's doctor, Emil Bessels, diagnosed apoplexy -- a stroke.

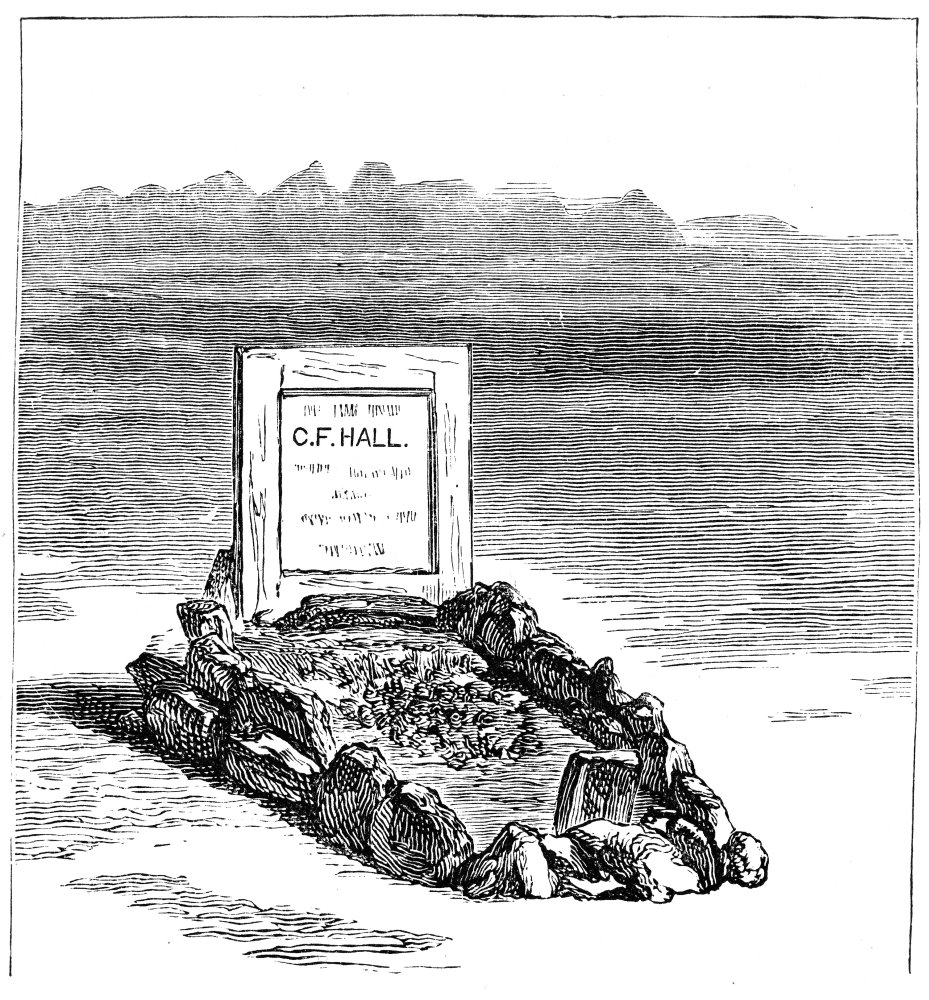

Bessels and Hall had quarreled in the past. Confined to his cabin, Hall accused the doctor of trying to poison him. Hall had also fallen out with his old whaling captain pal, Budington. Nevertheless, the vomiting and delirium abated, and Hall seemed to be improving. But then on November 8, he died. They buried him in the tundra in Thank God Harbor.

The drama was far from over for the crew of the Polaris. The following summer, Budington managed to sail the damaged vessel south about 300km to near Etah, a temporary hunting community that later served as the base for several white explorers.

Morale continued low. Then the ship was caught in the pack ice and was in danger of being crushed. There was a call to abandon ship, and 19 of the crew took refuge on the ice, along with some supplies that had been hastily thrown overboard. At that point, the damaged ship unexpectedly broke free of the pack and drifted off, leaving the 19 behind. We wrote about their ordeal, perhaps the most miraculous survival in arctic exploration, in a previous article.

The Polaris itself was eventually shipwrecked near shore, but the crew remaining on board survived the winter. Then, the following summer, they sailed their small boats south, where a whaling ship picked them up.

Detective work

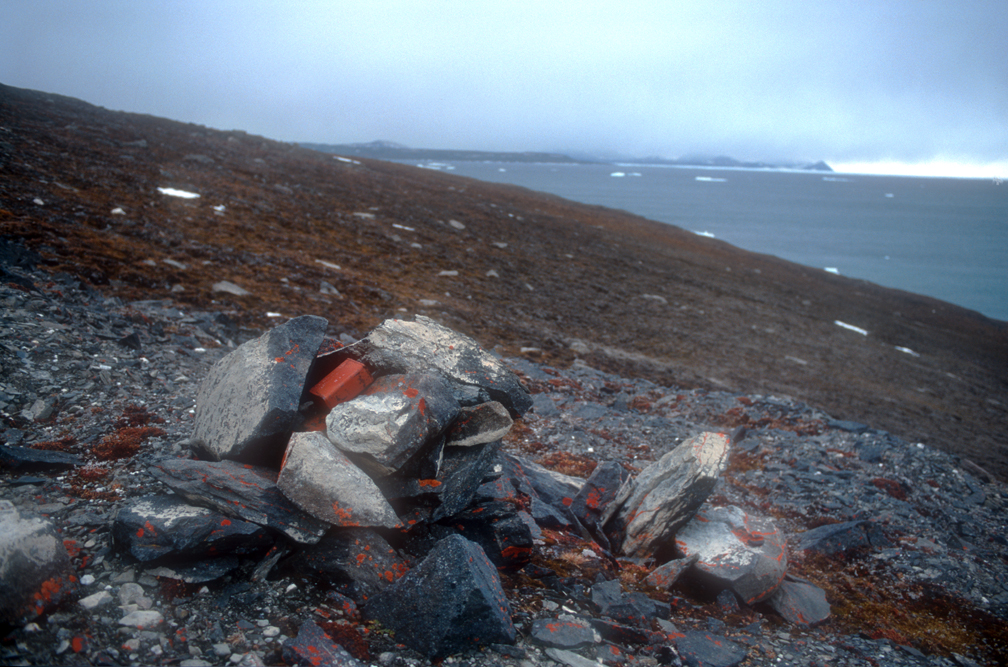

But what had happened to Charles Francis Hall? The mystery persisted until 1968, when writer Chauncey Loomis went to Thank God Harbor and exhumed Hall's body. The dry cold had preserved it for over a century. They took samples of his bones, fingernails, and hair, then reburied the body. Back south, they analyzed the samples and discovered that Hall had died not from a stroke but from large amounts of arsenic consumed during the last weeks of his life.

Arsenic was a component of the ship's medical kit, as it featured in many quack medicines of the day. Suspicion fell on the doctor, Emil Bessels. "If Hall was murdered, Emil Bessels is the prime suspect," Loomis later concluded in his fascinating book Weird and Tragic Shores.

However, Hall also had his own medical kit and might have accidentally self-administered the arsenic through some patent medicine.

We'll never know whether Hall was murdered or died unwittingly by his own hand. But in recent years, arctic scholar Russell Potter found an intriguing connection between Hall and Bessels that may have given the German doctor a motive other than personal dislike.

Vinnie Ream

Before sailing on the Polaris, Hall and Bessels both made the acquaintance of a beautiful young sculptor named Vinnie Ream. Ream "was attracted by [Hall's] bear-like quality...but Bessels became instantly infatuated with her," according to a source cited by Potter. Both Hall and Bessels later wrote to Reams. Could this have spurred the doctor to rid himself of a romantic rival?

Other articles in this series:

Murder Near the North Pole, Part I: The Death of Ross Marvin

Murder Near the North Pole, Part II: Death on an Ice Island

Murder Near the North Pole, Part III: The Death of Peeawahto

In 1914, explorer Fitzhugh Green shot and killed his Inuit guide Peeawahto. Green was a member of the Crocker Land Expedition, which set out to find a mysterious island that Robert Peary allegedly spotted off northwestern Ellesmere in 1906.

The expedition leader, Donald MacMillan, had been north once before, as one of Peary’s assistants. An ambitious man, MacMillan hoped that the discovery of Crocker Land would make his reputation. The expedition was affiliated with the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH).

The published account of the murder had always seemed strange to me. In a storm on northern Axel Heiberg, Fitzhugh Green’s dogs are buried and die. Peeawahto won’t slow down for Green, who is on foot. Green, convinced that he is being abandoned, shoots Peeawahto in the back, appropriates his team, and rejoins the others. MacMillan’s laconic summary of the event: “Green, inexperienced in the handling of Eskimos…had felt it necessary to shoot his companion.”

Searching for clues

Except for one brief detour, I’ve covered the Crocker Land Expedition’s entire route from Greenland to the northern tip of Axel Heiberg. In particular, to better understand the murder, a partner and I manhauled 700km to the scene of the crime near Cape Thomas Hubbard. I then visited Bowdoin College in Maine and the AMNH in New York to look over the expedition journals.

Bowdoin College has Green’s journal. Between the tattered brown covers and pemmican stains, fear lurks between the grandly penciled lines. Green would write some forty books in his life, all bad. But the journal is, at its key moments, unaffected. It shows a man overwhelmed with panic.

MacMillan’s journal is in New York.

“Not our favorite topic,” commented the librarian when I asked for Crocker Land material. “Wasn’t someone killed on that expedition under museum auspices?”

At the AMNH, I found the photo of Peeawahto that heads this story.

The expedition begins

The Crocker Land Expedition overwintered in Greenland. The following February, with an army of 19 men, 15 sleds, and 165 dogs to lay depots, MacMillan set out for northern Axel Heiberg and the Arctic Ocean.

As they advanced and laid down supplies, all of MacMillan's party turned back to Greenland except MacMillan, Green, and two Inuit, Etukashu and Peeawahto. Peeawahto (Piugaattoq, in modern orthography) had previously served with Frederick Cook, as well as with Peary and Knud Rasmussen, who described him as “a comrade who was ready to make personal sacrifices in order to help and support his companions.”

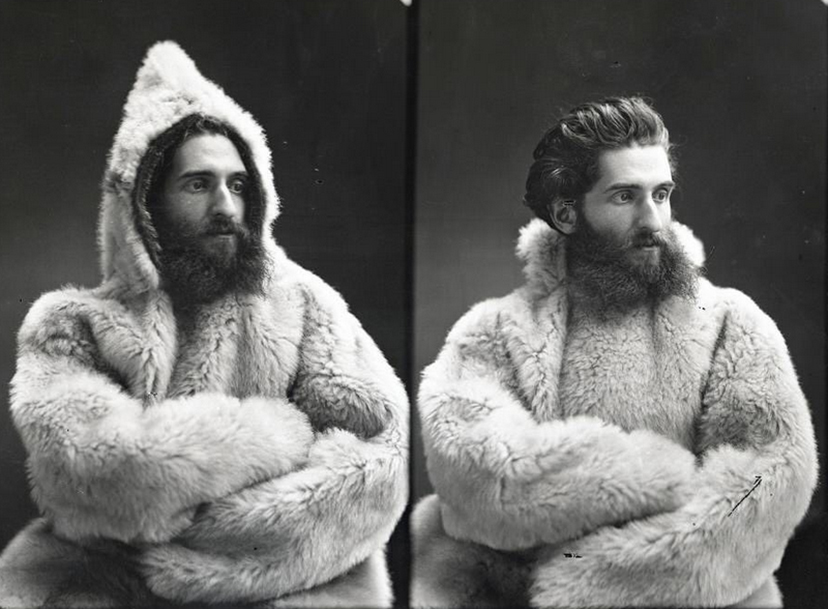

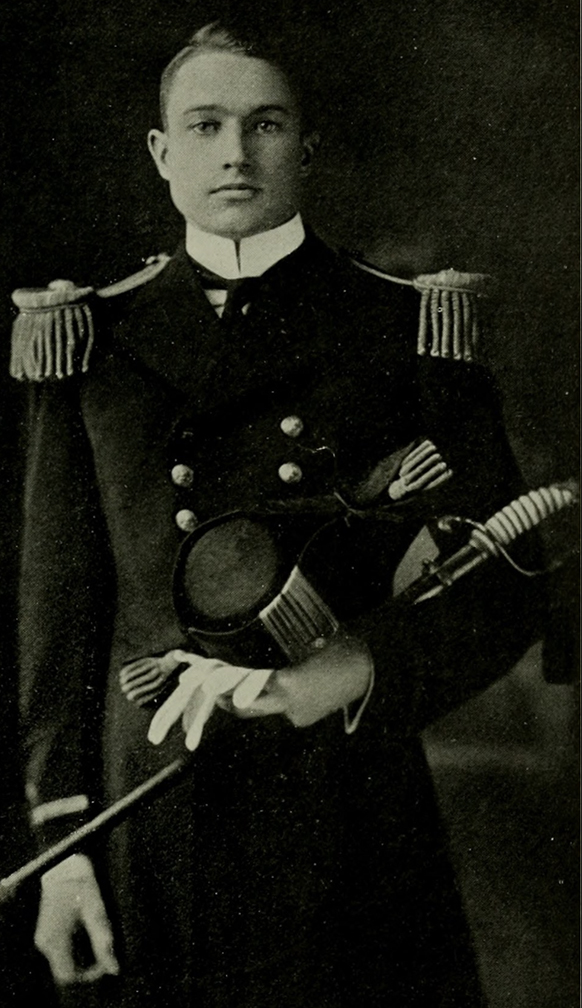

Fitzhugh Green, a 25-year-old naval ensign, came from good old stock. His great-great-grandfather had been a large Virginia landowner in the 1600s. As a young man, he was talkative and ingratiating, with a tendency to fawn over his betters –- and he expected those whom he considered his inferiors to defer to him. This made his dealings with the Inuit condescending at best.

Cringeworthy

MacMillan and Green fancied themselves the dauntless explorers leading the happy-go-lucky, childlike Eskimo. Green's posturing, in particular, was cringeworthy:

“Their life was a sublimely simple fight for food and clothing,” he wrote later. “Mine was a cruel struggle of such labyrinthine intricacy that only the genius could be rich and none be truly contented save the shrewdest philosophers.”

Spring weather is usually good on Ellesmere, but 1914 featured one gale after another. Fighting the north wind was exhausting. Once Green fell asleep chewing his supper. They couldn’t spot wildlife in the blowing snow. Dogs died, and men went hungry. Worried entries about the worn-out dogs recur daily in Green’s journal.

A good spot for a murder

Eureka and Nansen Sounds separate Ellesmere Island from Axel Heiberg Island. As you move up Eureka Sound into Nansen Sound, the high ice cap of Axel Heiberg tapers to low hills. Western storms can now deposit their snow on upper Nansen Sound. The very names reflect the moister climate. Ellesmere’s Black Mountains yield to the White Peninsula.

The mood changes, too. Even in a gale, Eureka Sound feels protected. But as Nansen Sound opens into the Arctic Ocean, there is nothing but exposure. It is the wildest place I've ever seen, a good spot for a murder.

On April 14, MacMillan, Green, Etukashu, and Peeawahto struck northwest across the Arctic Ocean toward the hypothetical Crocker Land. Incredibly, they managed to travel 250 kilometers offshore, but of course, they found nothing. There was nothing to find.

“I could plainly see that the Eskimos were discouraged,” MacMillan confided in his journal. “Peeawahto did not like the looks of so much open water so late in the year.”

As they headed back to land empty-handed, Green and MacMillan walked to lighten their load. Etukashu and Peeawahto rode, as Greenlanders always did.

They hurried to reach Cape Thomas Hubbard at the northern tip of Axel Heiberg, averaging 50km a day. They touched land on April 28.

A fateful assignment

Since Crocker Land didn’t exist, MacMillan must have felt pressured to bring back as many extras as possible. So although the dogs were exhausted and Peeawahto and Etukashu were impatient to get home, he proposed a four-day split-up.

He and Etukashu would cross Nansen Sound to revisit old Ellesmere cairns. Meanwhile, Green and Peeawahto would close the ring on Axel Heiberg by covering its last unexplored section, the fifty kilometers between its northern tip and latitude 80°55' on the west coast. Here they were to retrieve Sverdrup’s 1900 cairn message. “All the adventurous blood in my veins boiled up at the prospect,” wrote Green later.

Sverdrup’s end cairn has eluded the handful who have looked for it over the last hundred years. It is a great prize. In it, Sverdrup left a note declaring sovereignty over the arctic islands for the King of Norway.

On one manhauling trip, my partner and I spent a day and a half scouring the shoreline for it. We focused on the north side of a small, unnamed bay, which most closely matched Sverdrup’s description. Sverdrup and one of his men spent hours building the cairn. It must have been sizeable, but in an open landscape where nothing manmade escapes notice, we found no trace.

A blizzard hits

Green and Peeawahto never got that far. Shortly after separating from MacMillan on April 29, 13km southwest of Cape Thomas Hubbard, the worst storm of the year hit. It became so violent that Peeawahto quickly built a small igloo near shore, and they sheltered inside it.

For the next two days, Green’s journal becomes almost raving. Their stove doesn’t work. Drifting snow keeps plugging their igloo’s ventilation hole. “I was about done for,” he writes. “It was black as night in the hole.”

The next day, April 30, the wind drops a little, and they go outside and dig out Peeawahto’s sled. Green claims that his own sled and dog team are “under 15 to 18 feet of hard-packed snow,” so he gives them up for lost. “We cannot move yet, although to stay here is almost suicidal,” he says.

Retreating to the igloo, they try to melt snow for tea but have more trouble with the stove. “P. refused to make a hole in the roof…The fumes made us both sick, and I vomited several times.”

Conflict and murder

In the early hours of May 1, the wind briefly dies, and Green wants to continue to Sverdrup’s cairn. Peeawahto refuses, saying that MacMillan had instructed them to proceed just one day down the coast.

“I told him that I was master now until we got back to Mac,” says Green, although the argument becomes academic when the storm rises again, and they have to retreat to the igloo.

A little later, they begin their retreat with the one dog team. Green walks to keep his feet warm, but he cannot keep up with Peeawahto, who rides the sled. The storm picks up yet again. A panicking Green orders Peeawahto to slow down. To emphasize his point, he takes the rifle off the sled. But a few minutes later, Peeawahto begins to pull away again.

I fired once in the air, but he kept on. Then I fired twice, knocking him off his komatik. The dogs stopped. I ran up and found the man unconscious. I lashed him onto the komatik…

I must have wandered about for six or eight hours trying to find a familiar landmark. Finally I recognized a rock on the shore and headed for the igloo…

I finally got the snow cleared out somewhat [and took] P. in first. When I tried to do something for him, I found that he was dead.

The situation is an unhappy one. Here I am in a howling blizzard with a dead Eskimo, a strange team, and a few soaking or frozen garments…

Heroic posturing

Green’s later accounts fill in some details that his journal omits. The murder weapon was Peeawahto’s .22 Savage. At the first shot, Peeawahto slumped against the sled’s upstanders. “As the dogs did not stop, I thought that possibly he might still be alive so I shot again, splitting his head open so that his brains fell out.”

With a macabre presence of mind, Green removed Peeawahto’s kamiks –- his own footwear was falling to pieces. They didn’t fit. Green couldn’t stand the dead man’s eyes staring at him in the igloo, so he dragged the corpse outside and left it behind an ice block.

He continues his heroic posturing: “I kept wanting to say, ‘Peeawahto, you lucky dog, it’s all over for you. For me, it’s hundreds of miles of hell, with all the pain and misery of hell, and not one degree of its heat!’ But I wouldn’t let myself say it. I was afraid of being afraid.”

Green retreated the next day toward Cape Thomas Hubbard with Peeawahto’s team. The storm had also forced MacMillan to abort his journey, so he and Etukashu were camped nearby. “Mac, this is what is left of your southern division,” announced an exhausted Green when he pulled up on May 4, driving Peeawahto’s team.

“Good God, Green, is Peeawahto dead?” asked MacMillan.

Scared for his life

Green sketched out the story. Etukashu knew some English and overheard their conversation, but scared for his own life perhaps, he appeared to accept their explanation that Peeawahto had died in an avalanche.

“Etukushu took the news of his friend’s death very complacently,” wrote Green, “and was pleased with Peeawahto’s kamiks, which I brought.”

The wind continued to roar over Eureka Sound on their homeward march. On May 20, they reached their cache on eastern Ellesmere, just 50km across the frozen sound from Greenland.

“What a wonderful day,” wrote Green, “all surprises!…We found the box of supplies: sweet chocolate, marmalade, canned pears and peaches, hash, and a can of corn. My, we were happy!”

Back in Greenland, they continued to maintain that Peeawahto had died during the storm. Thanks to Etukashu, the villagers knew better but said nothing. At least one member of the Crocker Land Expedition was disgusted.

“[Green] did not consider it murder,” wrote their doctor, Harrison Hunt. “Peeawahto was just a savage…I would have to live with and care for a man who had killed my friend…I found my anger hard to control.”

MacMillan unsympathetic

Even MacMillan was unsympathetic. “[Green’s] assertion that if he had permitted the Eskimo to escape with the sledge, dogs and food, he would have starved, is not a sufficient reason for killing one of the best Eskimos I have ever known.”

After his return to America, Green continued to show the total lack of shame that was his greatest asset. In a 103-page article for a naval publication, he prefaced the murder with paragraph after paragraph of poetic babble: “Every sense has its pleasurable side. Sight loves beauty. Hearing revels in music. For touch there is sensuous softness and smoothness…”

His description of the shooting itself is no less surreal. “He that had loomed hostile and a deceit between me and safety lay now crumpled and inert in the unheeding snow…I had baffled misfortune. The feeling sent red gladness to my anemic humor…The present was perfect, ecstatic… I laughed, not fiendishly, but because I was glad…”

Aftermath

Green never went back to the Arctic after 1917, but his four years in the White North allowed him to affect an explorer’s persona for the rest of his life. He lectured widely on his experiences. Many of his books and articles play up those arctic years. He wrote of “my friend Etukashu” and how “I lived with the natives for almost four years, so I know how wonderful they are.” At the same time, casual references to “darkies” and “small brown people” continued to make their way into his godawful prose.

Always a talented sycophant, Green was aide to an admiral, to the president of the Naval War College, and to book publisher George Putnam, for whom Green wrote a gushing biography of Robert Peary. He followed with a biography of yet another arctic faker and establishment hero, Richard Byrd.

The incident does not seem to have harmed Green personally or professionally. He died in glory and honor, and his jottings and family photographs are now preserved at Georgetown University in Washington, D.C.

In 1970, the world’s northernmost murder took place on the drifting ice island T-3, 350km northwest of Ellesmere Island, on the Arctic Ocean.

Ice islands were big, flat pans of ice that broke off from the 3,000-year-old ice shelves that until recently, clung to parts of northern Ellesmere. They've almost all disappeared now -- broken away, melted -- but they used to be important platforms for research. Unlike sea ice, these giant platforms lasted for a couple of decades. They were so big you could land large supply planes on them.

The first one was discovered in 1946 off Alaska by a U.S. spy plane. It was classified top-secret because of its value as a base. They all came from Ellesmere Island but they could drift thousands of kilometers. Eventually, they broke up.

Since 1952, researchers under the U.S. Air Force had occupied T-3 -- sometimes called Fletcher's Ice Island after the pilot who discovered it -- almost continuously. At first, it was 52km across and 60m thick, but by the time of the murder, it had shrunk to 11km long, 6.5km wide and 30m thick.

Researchers lived in trailers and communicated with the outside world via high-frequency radio. Planes could not land on the uneven, watery summer ice, and T-3 was well beyond the range of helicopters, so the 19 men were on their own for months.

Hard-drinking misfits

In that era, such isolated outposts drew a lot of hard-drinking misfits. “Porky” Leavitt was one of them. He had already attacked three people in the camp in his quest for alcohol.

On July 16, 1970, Mario Escamilla heard that Porky had just gone into his trailer and stolen some homemade raisin wine. The doors to individual trailers did not lock on the ice island. Escamilla had been attacked by Porky before, so he brought along one of the camp rifles for protection.

He found Porky next door with the station manager, Bennie Lightsy, drinking raisin wine spiked with pure ethanol. Escamilla told Porky to stay away from his wine and went back to his trailer.

Presently, he heard footsteps. Thinking it was Porky and fearing for his safety, he picked up the gun and flipped the safety off. Bennie Lightsy entered, so thoroughly drunk that his blood alcohol was later gauged to be around .26 -- at least 12 drinks for an average-sized man.

The two argued about the wine. Escamilla ordered Lightsy to get out of his trailer and continued to brandish the rifle as the argument heated up. The gun went off accidentally, wounding Lightsy fatally. He died soon afterward.

Murder in legal limbo

Legally, T-3 was an awkward spot for a homicide. An ice island was neither land nor ship. It did not belong to anyone. T-3 originated in Canada, but it was a U.S. station manned by Americans. Although maintained by the Air Force, its civilian personnel were not subject to military law.

Ice islands simply did not exist in international law. Lightsy’s death had occurred in one of those rare jurisdictional gaps where serious crimes might go untried. Murder in Legal Limbo, declared the headline in Time magazine.

Ultimately, Escamilla was tried as if it had taken place on the high seas. In 1971, he was found not guilty of second-degree murder but guilty of involuntary manslaughter. He was sentenced to three years, but his appeal turned up enough procedural flaws to win a new trial. In the retrial, Escamilla was acquitted.

The ice island itself melted away in 1984.

In 1909, a young American, Ross Marvin, was helping Robert Peary on his last North Pole expedition. Marvin did not survive. He supposedly fell through a crack in the sea ice and drowned. Years later, it came to light that his death was no accident.

While part of the joy of expeditions is the deep bond that can form between partners, the chemistry doesn't always go well. Arctic exploration, in particular, can be so stressful that several murders and near-murders have occurred. Henry Hudson and his son were set adrift in a lifeboat by a mutinous crew and never seen again. Elisha Kent Kane almost killed one of his troublesome men by bashing his skull with a belaying pin. Charles Francis Hall was likely poisoned with arsenic by his ship's doctor. On an American expedition in 1914, a privileged young man named Fitzhugh Green panicked in a storm and shot his Inuit companion Peeawahto, thinking Peeawahto was abandoning him.

Erratic behavior

The Inuit sometimes killed people too, including white visitors. Occasionally, white men behaved so erratically that the Inuit considered them dangerous. That was the case with the overbearing trader Robert Janes on Baffin Island. His 1920 murder led to the first case in which an Inuit man was prosecuted under white man's law.

And then there was the curious case of Ross Marvin.

Ross Marvin.

Ross Marvin was a Cornell University graduate who had accompanied Peary once before, in 1905-6. On the ship, Marvin served as the aging explorer's secretary. But in 1909, he headed a four-person team composed of himself and three Greenlanders -- Kudlooktoo (Qilluttooq in modern orthography), his cousin Inukitsoq, and Aqioq. Their job was to shuttle loads forward over the Arctic Ocean so that Peary, at the apex of this pyramidal system, could advance quickly with a light sled toward the North Pole.

Marvin's personality

Accounts of Marvin's personality -- which is relevant to this story -- differ widely. Peary's longtime manservant Matthew Henson described Marvin as "a very quiet young man, but one of great courage and strength of character...cool-headed, quiet, and just.”

Peary, a difficult man whose word must always be taken with a grain of salt, was also complimentary: “Quiet in manner, wiry in build, clear of eye...[Marvin's] good humor, his quiet directness, and his physical competence gained him at once [the Eskimos’] friendship and respect. From the very first, he was able to manage these odd people with uncommon success.”

Others, however, described Marvin as someone who never laughed, even "a pain." Inukitsoq claims Marvin threw a tantrum after Inukitsoq had followed Kudlooktoo, not Marvin, around a lead -- an open water crack in the sea ice.

“Suddenly, we became afraid of him,” Inukitsoq reported years later.

Polar controversy

Marvin accompanied his commander as far as 86˚38' north before Peary sent him back to land. It is unclear how much further Peary got, but modern historians accept that while Peary claimed he reached the Pole on April 6, he fell significantly short, and he knew it. He had sent back not only Marvin but all the white companions who could verify his navigation. He kept only Henson and two Inuit with him.

Meanwhile, Marvin and his small party struggled to return to northern Ellesmere Island. They crossed dangerous patches of thin ice; twice, Marvin fell in the water and was rescued by his companions. On the third occasion, the Inuit later reported, Marvin drowned.

After Peary returned to the ship in late April, he learned of Marvin's death. He had a cairn built for the young man, topped by a cross with a memorial plaque. The cross and plaque toppled from the cairn but still lean against it at Cape Sheridan today. The plaque's wording, neatly done in stippled lettering with a hammer and some kind of metal point, states: “In memory of Ross G. Marvin, Cornell University, aged 31. Drowned April 10, 45 miles N of Cape Columbia, returning from 86° 38’ N. Lat.” (Marvin was actually 29.)

Aftermath

When Peary returned to civilization, he notified Marvin's parents by telegram of their son's death. In typical Peary style, he sent the telegram collect.

By then, he was embroiled in something much more important to him: He had to discredit Frederick Cook, who said he himself reached the North Pole a year earlier -- a claim now also recognized as false. And Peary had to defend his own claim. Despite several glaring holes in his account, Peary eventually won the battle. He was almost universally recognized as the "discoverer" of the North Pole until the 1960s when the doubts began to resurface.

Fourteen years after that North Pole expedition, in 1923, Kudlooktoo converted to Christianity and was baptized. He wanted to clear his conscience and confessed that the story of Marvin drowning in a lead was false.

“After my baptism, I did not want to keep this murder secret,” Kudlooktoo stated.

It turns out he had shot Marvin in the back of the head, pushed him into the water, and then concocted the drowning story with his two Inuit companions.

What happened on the ice

What happened was this: On their way back from their Farthest North, a stressed and frostbitten Marvin behaved impatiently. He forced the party to cross stretches of thin ice rather than wait for it to freeze more thickly, as the Inuit advised. When young Inukitsoq fell sick, Marvin ordered the others to abandon him.

As mentioned above, it had happened before in the Arctic that when white explorers behaved in a way that the Inuit considered a danger to themselves, execution was regarded as a rational solution. Kudlooktoo shot Marvin in order to save Inukitsoq.

In 1925, the Greenland explorer and ethnologist Knud Rasmussen heard the story of Kudlooktoo's confession and spoke to Kudlooktoo to verify the details. Rasmussen then reported it to the Danish government and brought the news to the United States.

In 1926, there was pressure to extradite Kudlooktoo to the U.S. to face charges. But Denmark then suggested that in that case, they would ask that Fitzhugh Green be extradited to Greenland to stand trial for the murder of Peeawahto in 1914.

In the end, neither man was ever charged.

A lot of contemporary adventure is long on athletics and short on imagination. Is it really exceptional any more to jumar the South Col route on Everest? Or to be the 1,401st person to climb Mount Vinson in Antarctica?

Some might argue that the great adventures have already been done, but even that is not true. The last successful North Pole expedition was 10 years ago; only one party has gone to the North Pole and back to land; no one has done a solo round trip. No one has skied entirely across Antarctica. The first kayak expedition entirely through the Northwest Passage only took place last year; no one has kayaked the ice-choked and even more difficult northern route through that Passage. Hiraide and Nakajima perished this past fall, attempting the unclimbed West Face of K2. No one has reached the North Magnetic Pole since the 1980s, before it began its tear across the Arctic Ocean toward Russia. There is still a lot out there, even for iconic goals.

Admittedly, it's easiest to find original routes that aren't as well-known as the North Pole or K2. Canada's Justin Barbour did that this year. The former Newfoundland school teacher turned content creator spent an entire year traveling 3,800km from Puvirnituq, in northern Quebec on the shores of Hudson Bay, to Cape Pine, the southern tip of the island of Newfoundland.

Puvirnituq? Cape Pine? Not exactly iconic. Likely, no one will ever re-do this journey. It's a one-off. But give Barbour marks for that. It shows imagination to figure out your own path. It also suggests someone educating himself about the land, not just copycatting the one or two routes he's heard about.

A full year

“I want to experience a full year in the northern wilderness," Barbour told ExplorersWeb before the journey. "To experience the four seasons as the indigenous people of the area have."

Barbour first came to ExplorersWeb's attention in 2018 when he tried to trek and canoe 1,700km through the same general region from Labrador to Hudson Bay. He started late and had to abort after about 1,000km as winter set in.

"I had enough summer experience, but my winter skills in the subarctic cold weren’t there yet," he admitted.

Six years later, the 36-year-old Barbour is more experienced. He started in early July of 2023 at Puvirnituq, an Inuit village with a population of about 2,000 on the shores of Hudson Bay. Thirty-eight days and 692km of downriver paddling and upriver canoe hauling with his dog Saku, he arrived at his first checkpoint, the village of Tasiujaq on James Bay.

Waiting for winter

It was mid-August, and a chill was already in the air, as the short arctic summer quickly turned to fall. Barbour continued south in his canoe, trying to make 700km to his next stop, the former mining town of Schefferville, before winter set in.

He didn't quite reach it. A helicopter pilot friend conveyed him to Schefferville. He lived for a few weeks in his heated bush tent outside of town, as he waited several weeks -- like the trappers and Innu people of the interior used to do -- for the brooks and lakes to freeze solidly and for the new snow to harden under the region's bitter northwest wind.

Finally, on Jan. 4, 2024, his pilot friend conveyed him back north to his pickup point. Saku, a fair-weather dog, had gone home. Barbour continued south alone on snowshoes, hauling a traditional-style toboggan with a single leather strap across his chest. That was how Labrador's old Height of Land trappers did it. These toboggans are longer and narrower than kids' versions and have high, upturned noses for riding over snowdrifts.

Skis and a fiberglass pulk, like those Antarctic skiers use, would be quicker, but Barbour preferred a traditional style. And his canvas tent, hung from a frame of black spruce trees and heated by a small wood stove, is far more comfortable than a nylon tent in the frigid northern Quebec interior, where temperatures can drop well below -50˚C.

Spring arrives

He stuck as much as possible to open lakes, where the snow was harder than in the open forests of black spruce and tamarack. After several hundred kilometers, he crossed the Trans-Labrador Highway, a wilderness road that connects Labrador with the rest of Canada, and then continued south overland toward the Gulf of St. Lawrence.

But spring was coming on, snow cover was thinning out, forests were thicker, and the south-flowing rivers he had to follow were opening up. The toboggan-hauling season had ended. Rather than wait a month for the rivers to open completely so he could canoe again, he had his helicopter friend convey him 267km back to the Trans-Labrador Highway. Here, he cycled 1,500km to the south coast of Labrador.

By this time, "I was starting to wear thin," he admitted. So he decided against kayaking the 18km Strait to the island of Newfoundland. Instead, he took a ferry across.

Then he hiked another several hundred kilometers to Cape Pine, the southern tip of Newfoundland. In the end, he spent his full year (372 days, to be precise) in the wilderness, traveling by a variety of conveyances -- 1,150km of canoeing, 700km of snowshoeing, 1,500km of cycling, and 550km of hiking.

Barbour admits he's not sure what he'll do next. Such long journeys disrupt every other aspect of one's life, and most ultra-marathon adventurers do only one of these before starting to put down roots. A follow-up project that lasts only one or two months may feel small by comparison, and most tend not to do them. But we'll keep watching Barbour's social media, just in case.

The Italian mountain site montagna.tv has listed ExplorersWeb's Angela Benavides as one of the 50 most influential mountain people of 2024.