The ice caps which cover our planet's poles are key to understanding global weather patterns and changing climate. But we still don't have a complete understanding of how they work, and what goes on beneath the frozen surface.

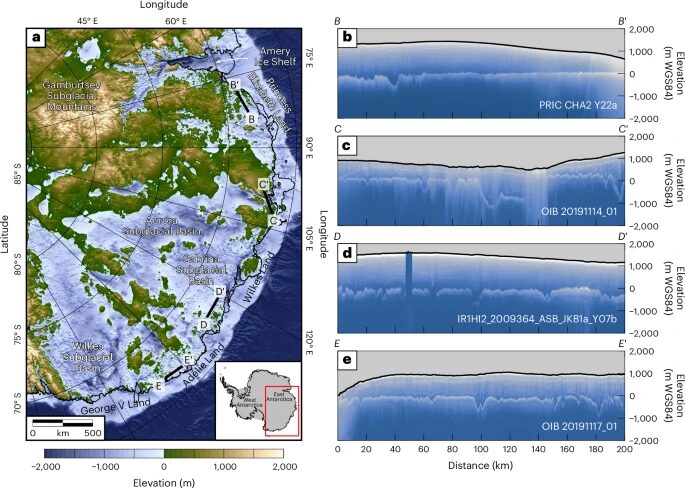

A group led by researchers at the UK's University of Durham used radar to glimpse beneath the coast of East Antarctica. In a new study, they announced their findings: Ancient riverbeds beneath Antarctica control the behavior of the ice sheet above them.

Reconstructing ancient landscapes

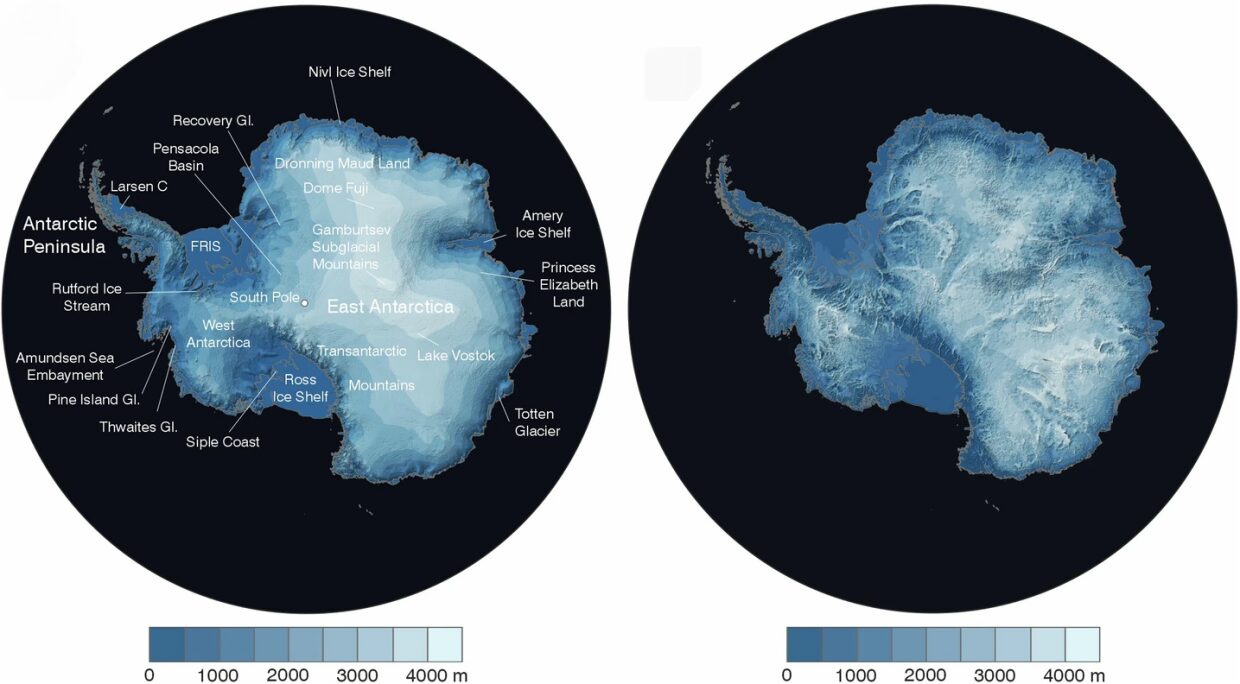

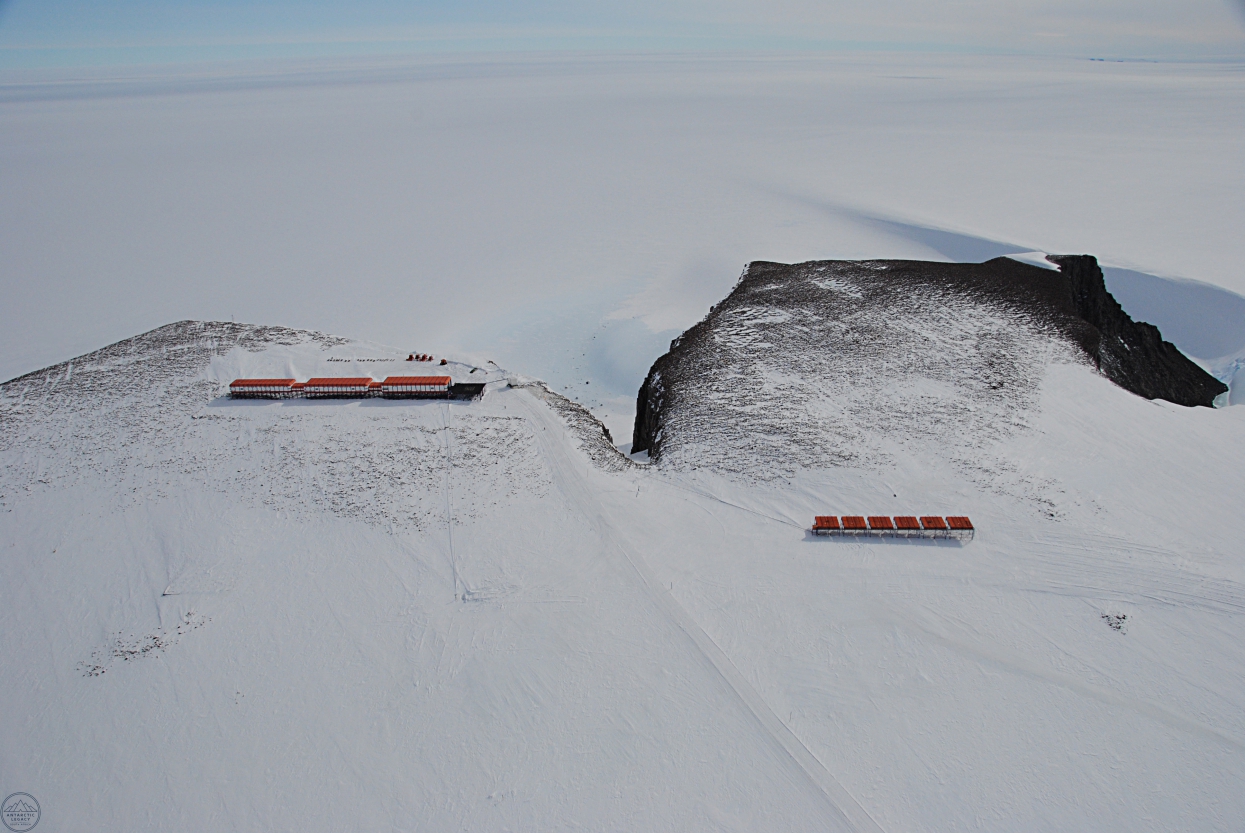

It is crucial to understand how much, and how quickly, the East Antarctic Ice Sheet is going to melt as temperatures continue to rise. It's the largest of Antarctica's three ice sheets, and it contains enough water to raise the sea level by over 50 meters.

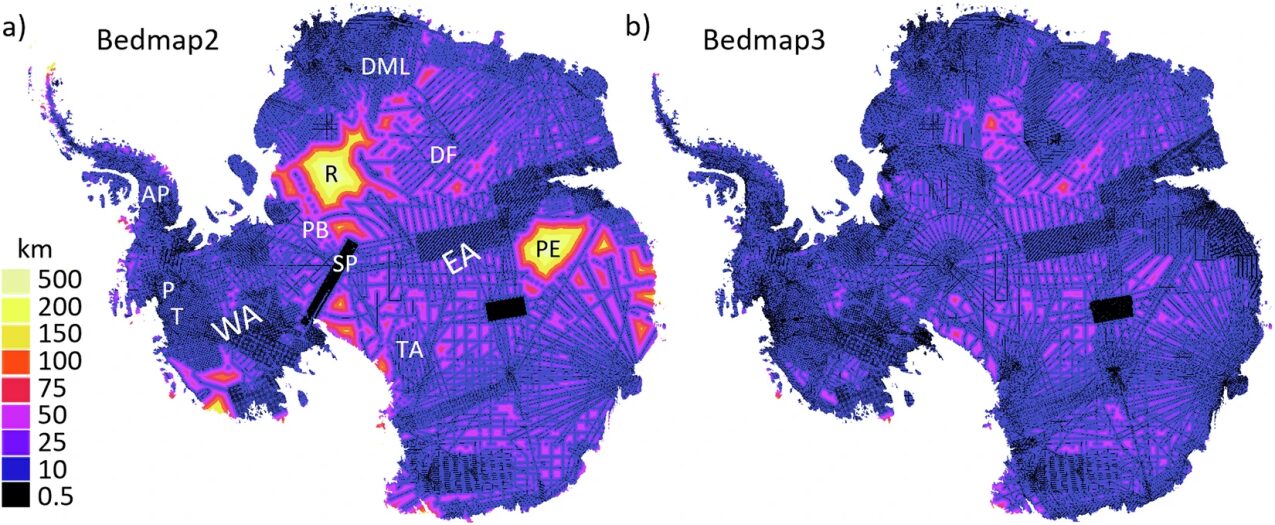

The behavior of an ice sheet depends on more than just surface conditions. The landmass hidden beneath the ice impacts how quickly it melts and where it collapses. To get an idea of what that hidden landscape looks like, researchers analyzed a series of radar scans covering 3,500km of East Antarctica.

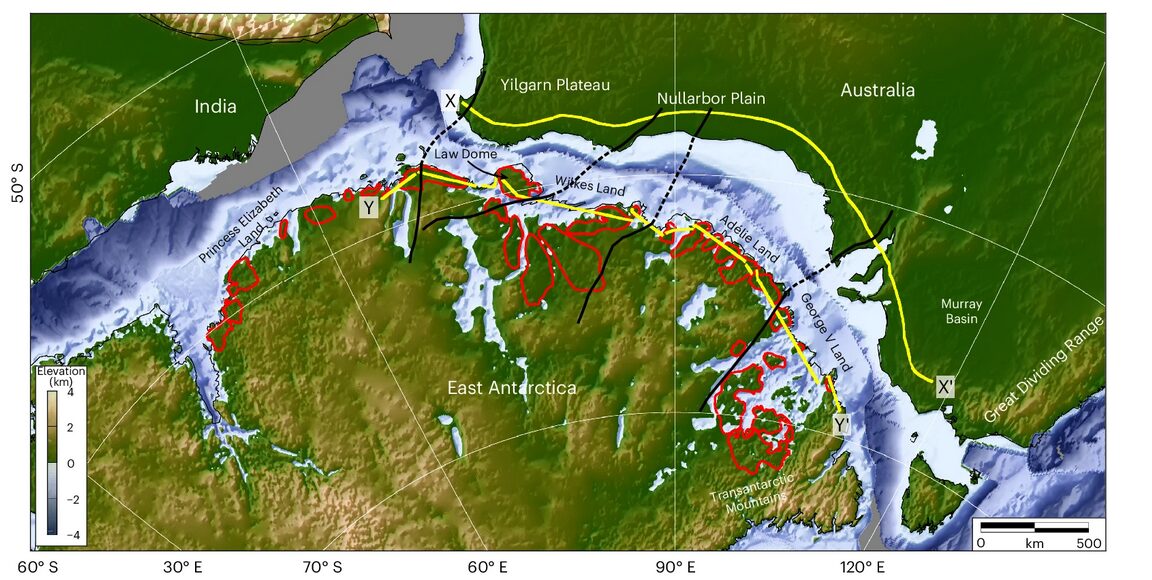

The scans found what was once a coastal plain formed by fluvial erosion. Between 80 million years ago, when Antarctica divorced Australia, and 34 million years ago when it became covered in ice, rivers flowed across East Antarctica and into the sea. Those rivers carved out a smooth, flat floodplain all along the coast. Breaking up the plain are deep narrow troughs in the rock. These plains covered about 40% of the area they scanned.

This find confirms previous, fragmentary evidence for a very flat, even plain beneath the icy expanse.

Hopeful findings

This is good news for those of us who enjoy not being underwater. Computer programs modeling future climate behavior now have more data to work on. Before, as the study's lead author, Dr. Guy Paxton, said in a Durham press release, "The landscape hidden beneath the East Antarctic Ice Sheet is one of the most mysterious not just on Earth, but on any terrestrial planet in the solar system."

Understanding the terrain beneath the ice makes it much easier to understand how and where the ice will move. “This in turn will help make it easier to predict how the East Antarctic Ice Sheet could affect sea levels.”

More than that, however, the ancient fluvial plains may be slowing down the melt. The study suggests that the flat plains may be acting as barriers to ice flow. Fast-moving glaciers pass through the deep channels, but the bulk of the ice, atop the plains, is moving much more slowly.

Ultimately (as they always do), researchers stressed the need for more investigation. Further studies would involve drilling all the way through the ice and taking samples of the rock below. So look forward to that.

"The North Shore invented mountain biking," claims Todd "Digger" Fiander, a trail builder and videographer. If the sport was indeed born in , Betty Birrell was there from the start.

North Shore Betty, a short film from Patagonia, introduces us to the eponymous Betty. Now entering her seventies, Betty reflects on what is means to be an older woman in the rough world of mountain biking.

One big playground

She didn't start in mountain biking. Betty first made a splash (pun intended) pioneering women's wave sailing in the early 1980s. By her mid-forties, she was a single mother and full-time flight attendant, but she also started mountain biking. She started riding Fiander's "roller coasters for bicycles" after getting her first mountain bike in 1993.

Rather than competing, Betty found that mountain biking and being a single mother worked together. It became an activity she could do with her son, and they still bike together now that he's an adult.

Betty also isn't afraid to get injured. She's broken an arm, a wrist, a hand, and "lots" of ribs, dislocated shoulders, and torn her rotator cuff, but it didn't, and still doesn't, bother her.

According to Betty, when her ex told her she treated life like it was "one big fucking playground," she took it as a compliment.

The short film interviews Lea Holt, a nurse with a family who worried, as she approached fifty, that she would have to give up mountain biking. But Betty's career changed her mind. "I have twenty more years..." Holt explained, "to get better."

"Betty is a legend on the North Shore," says fellow British Columbia mountain biker Amanda Moffat. When they ride together, she says, people will call out to Betty as they pass, like she was a celebrity.

Now 73, Betty plans to keep riding into her nineties. "Older people...need to know that you can keep going," she says. On the screen, Betty's bike leaps over rocky trails and races around bends and through the forests.

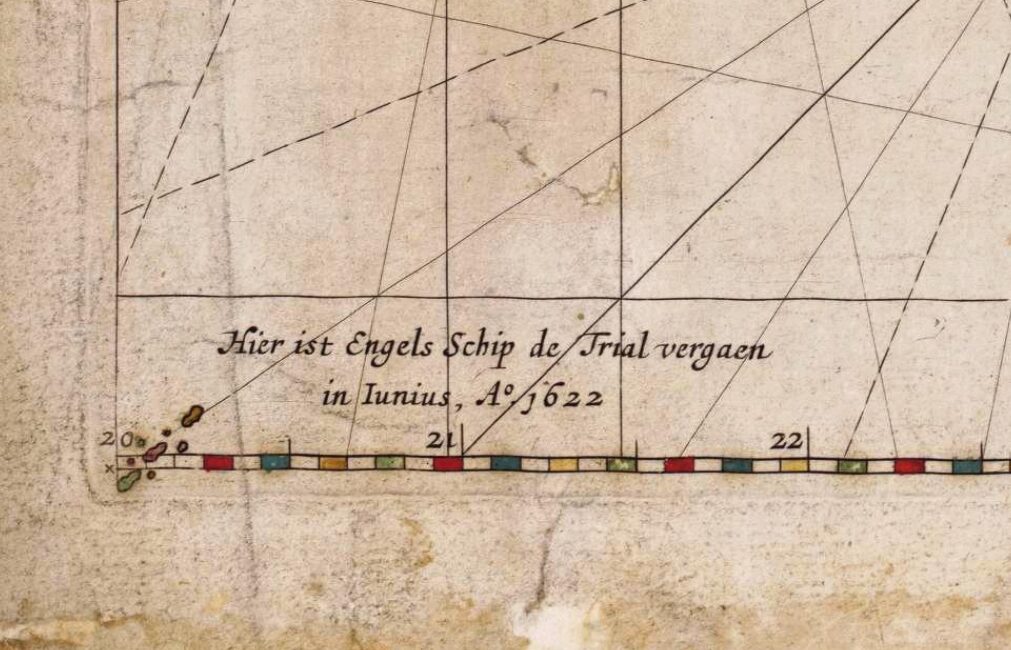

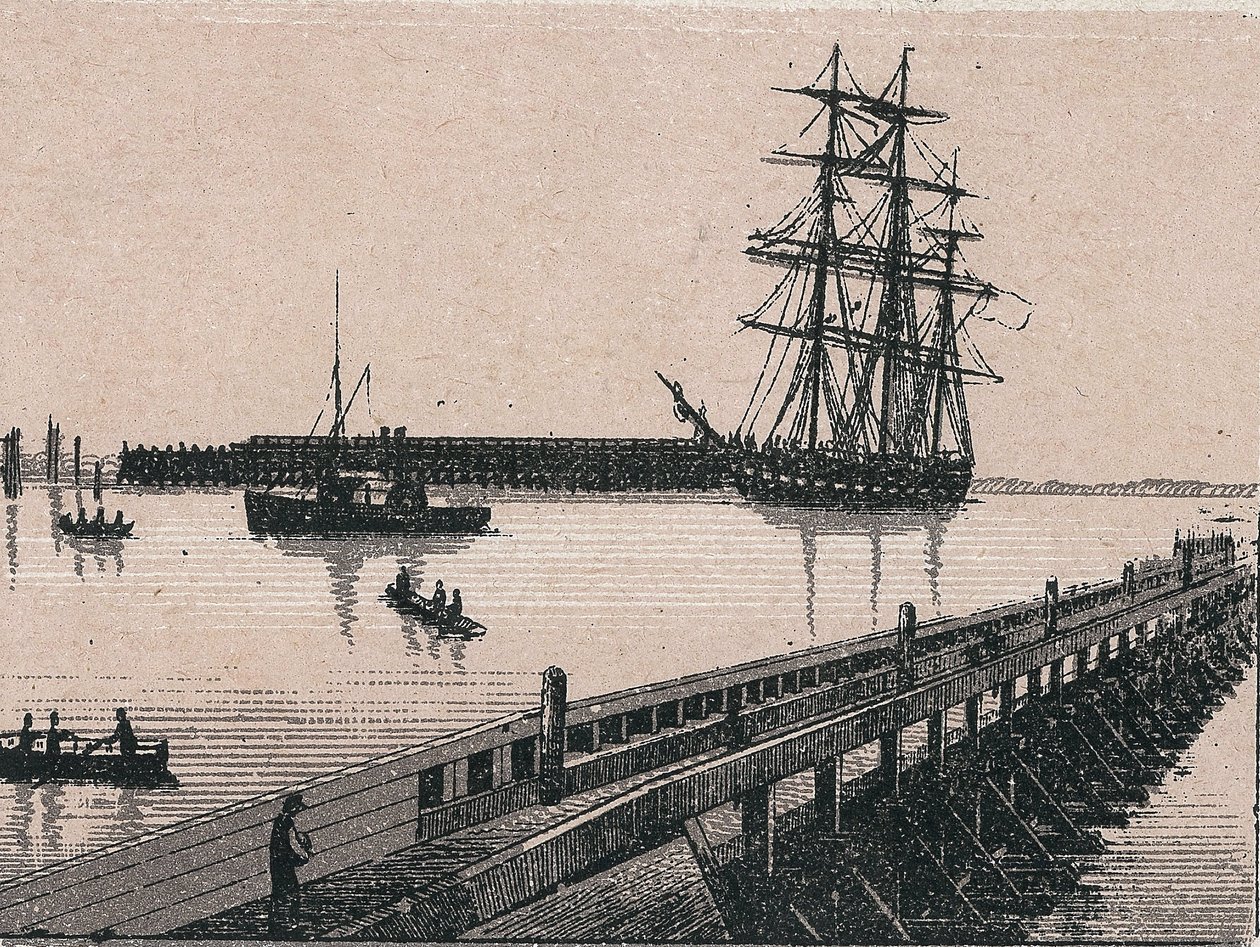

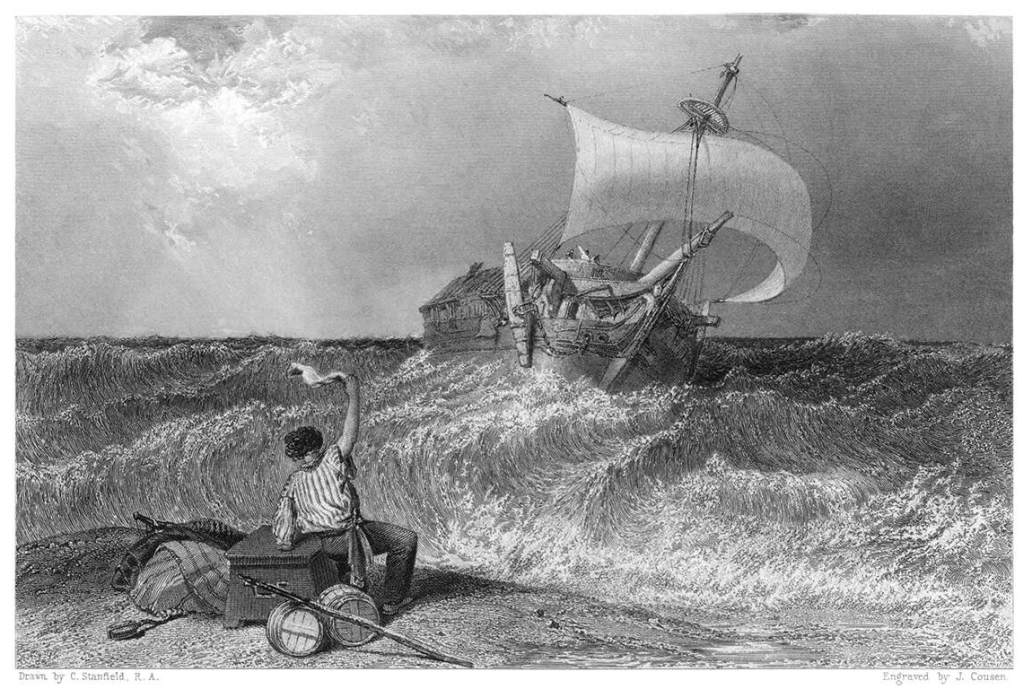

In May of 1622, the English East India Company ship Tryall became the first English ship to sight the coast of Australia. Shortly after, it became the first ship to sink off the coast of Australia.

The story of the Australia's oldest shipwreck covers 400 years, from a suspicious sinking to a pair of castaway journeys, a court case, a geographical mystery, and a modern scandal involving the misuse of explosives at an archaeological site.

The maiden launch of the Tryall

The Tryall (also spelled Triall, Tryal and Trial) set sail from Plymouth on Sept. 4, 1621. She was a British East Indiaman, a mercantile vessel built to travel between England and the Global Southeast, then called the East Indies.

Owned by the British East India Company, her generous hold was filled with textiles, silver, and supplies bound for Batavia -- present-day Jakarta, Indonesia. This was to be her maiden voyage, and an inspection by EIC officials at the docks found her in good condition.

Her Captain was John Brookes. The other key man aboard was Thomas Bright, the EIC's representative, or "factor" for the voyage. One hundred and forty-three seamen rounded out the crew, and after a brief pay dispute, they sailed for the Cape of Good Hope.

This stage of the journey went fine. They arrived at the tip of Africa, took on fresh supplies, and set off for Batavia on March 19. By a new, dangerous route.

Another way to India

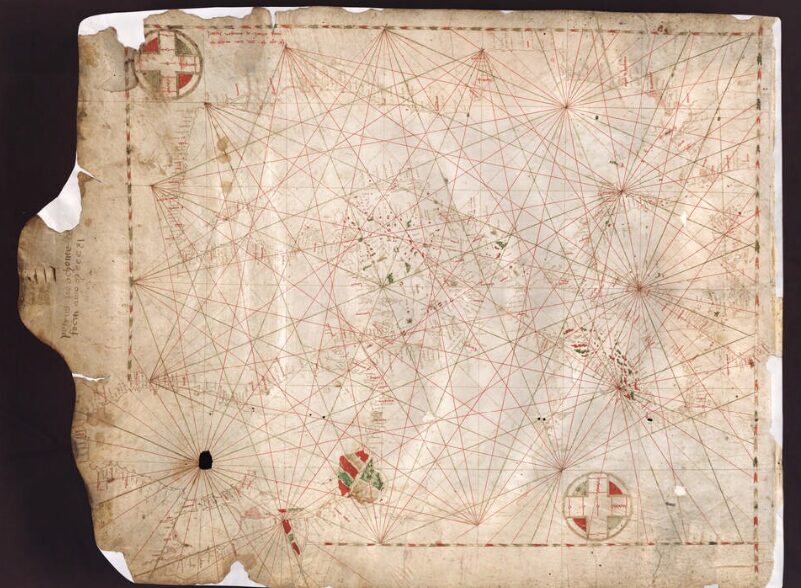

At the turn of the 17th century, the standard route from Cape Town to Batavia came from 15th-century Portuguese explorers, who used the seasonal monsoon winds to cross the Indian Ocean. It took about 12 months.

The Dutch decided that if they were going to steal the spice trade from Portugal, they had to do better than that. So Hendrik Brouwer took an alternative way in 1611. It became known as the Brouwer route.

The new route cut travel time in half by ducking down into the Roaring Forties and using their strong westerly winds to cross the Indian Ocean. The key was the timing of that northeast turn. Too early, and you'd end up in the middle of the Indian Ocean. Too late, and you'd crash into Australia.

They didn't know that yet, though. A few Dutch explorers had sighted some islands off the Australian mainland, but no one suspected a whole continent might be in the way.

The problem with that all-important turn is that, at the time, there was no good way to determine longitude at sea. Ships would have to make the turn using dead reckoning, which is a fancy nautical term for "guessing." In 1620, the British EIC decided to copy the Dutch and sent Captain Humphrey Fitzherbert to test the route.

He had a great time and gave it a thumbs-up, so they gave Captain Brookes a copy of Fitzherbert's journal and told him to do the same thing.

The wreck of the Tryall

Brookes was nervous about the new route. In Cape Town, he met Captain Bickell, another EIC Captain. He asked Bickell if he could borrow one of his experienced mates to help navigate, and Bickell gave him permission. But Bickell's ship, the Charles, was on its way home, and none of her mates were willing to delay their return to help.

Brookes had to sail on, with only the 1620 journal and imperfect charts as a guide. The Tryall descended to 39 degrees latitude, and the Roaring Forties drove them east.

On May 1, they spotted land. They had just become the first Englishmen to see Australia. Brookes and Bright both describe a great island, because from their perspective, a pair of points made the coast look like an island. Brookes turned north for the run up to Java, but was kept in place by contrary winds. Finally, on May 24, he was able to head north.

The next day, late in the evening, in calm seas, the Tryall struck rocks. Brookes ran up on deck, giving orders to tack west, hoping to dislodge her. A strong, brisk wind began to blow as water flooded into the ship, the sharp rocks tearing her timbers apart. It was too late, Brookes realized, to save her. He "made all ye meanes I could to save my life and as manie of my compa[ny] as I could."

He launched the ship's two boats. Ten, including Brookes, climbed into the skiff, while 36, including Thomas Bright, piled into the pinnace. Less than six hours after striking rocks, the fore-part of the Tryall broke up. Ninety-seven died.

Brookes' story

Brookes' skiff launched first. With him were nine sailors and a cabin boy, who would definitely be eaten first if it came to cannibalism. They had several cases of spirits and kegs of water, but only four pounds of bread. They landed briefly on a low island, now known to be Barrow Island, then set off again.

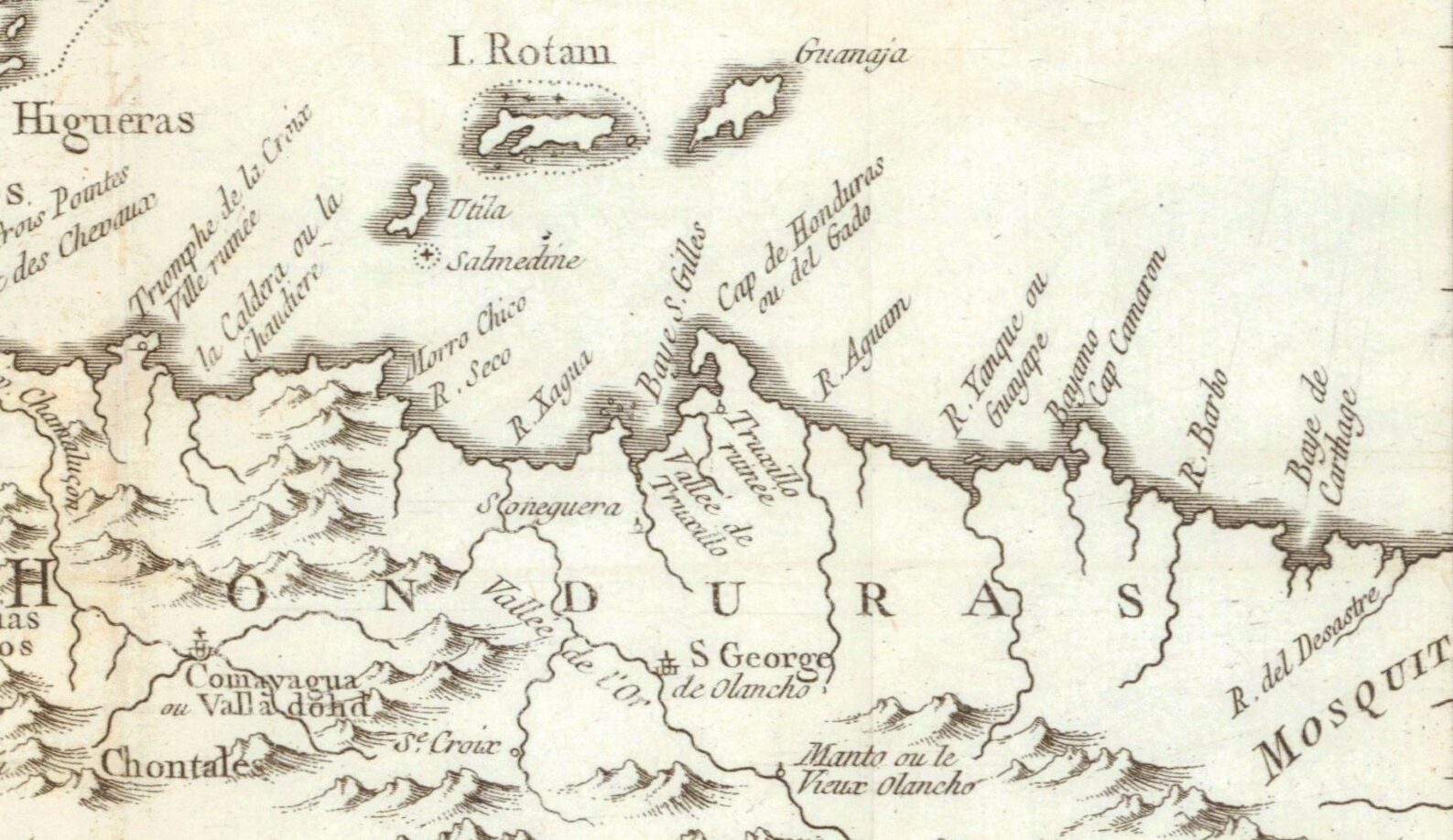

On July 5, they arrived in Batavia, and Brookes sent his report to his EIC superiors. Fitzherbert must have overlooked the land they sighted on May 1, he explained. "He went 10 leagues to ye Southwardes of this iland," Brookes asserted, before making the northeast by east turn. Brookes said that after sighting this land, he also made a northeast by east turn.

That Fitzherbert had missed the rocks was pure chance; his ships had sailed right past destruction without realizing it. The wreck of the Tryall could have happened to anyone. The EIC agreed. So they gave him another ship, the Little Rose, to explore the area around Sumatra. When he got back, they put him in charge of the Moone.

The wreck of the Moone

Brookes was taking the Moone back to England with a few other EIC vessels. But the Moone was wrecked off the coast of Dover, and with her went £55,000 worth of cargo, about $14,000,000 today. John Brookes and the ship's master, Churchman, began accusing each other of misconduct, and the EIC threw them into prison.

In court, Brookes made multiple lengthy speeches protesting his innocence. He also stressed, once again, that the Tryall wreck was not his fault. Regarding the Moone, Brookes blamed the ship's poor condition, calling it worm-infested and half rotten.

Witnesses, however, testified that he had discussed deliberately sinking the ship back in Cape Town. He was accused of deliberately sinking the ship in an elaborate heist of the valuable cargo. In fact, when the wreck site was examined, most of the cargo was missing. Multiple eyewitnesses also claimed Brookes had used the confusion of the sinking to break open and pilfer a chest of jewels.

The court case dragged on for years before finally being settled out of court. While he was never convicted, Brookes had lost all of his money and reputation. But with all the back and forth about stolen diamonds and the Moone, his claims about the Tryall went unchallenged. There was one man, however, willing to challenge John Brookes: Thomas Bright.

Bright's story

In a series of letters, Thomas Bright gave his side of the story. The fact that they'd hit the rocks at all, he claimed, was due to Brookes not keeping a proper lookout. Once the ship was struck, he described Brookes rushing to provision his own boat. He even personally betrayed Bright ("like a Judasse") by promising to take him, then launching the skiff while Bright wasn't looking. The skiff then made straight for Java without waiting to see what became of everyone else.

The pinnace, or longboat, launched an hour and a half after the skiff, with 36 men aboard. They had a couple of pounds of bread, some bottles of wine, and a single barrel of water. The sea was too rough to do anything but keep in sight of the crumpling ship, weathering the waves, until morning. In daylight, they made for a nearby island.

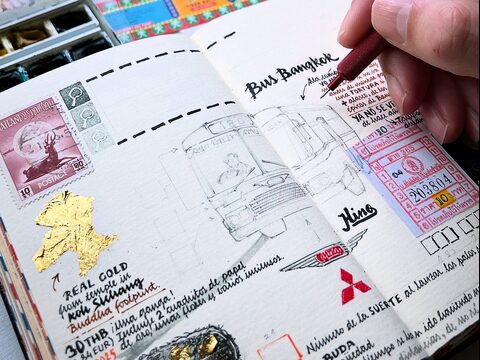

They spent a week on a low, uninhabited island, now known as North West Island. There, they repaired the pinnace and tried to stock up on provisions for the journey ahead. Bright kept himself busy drawing maps and charts of the surrounding area, becoming the first Englishman to map parts of Australia.

The pinnace successfully reached Java in late July. Bright was furious at Brookes and the lies he had been spreading. He wrote detailed letters and drew maps and charts laying out Brookes' deception -- but they went unheeded, and then were lost.

The search for the Trial Rocks

Both the British and Dutch East India Companies (referred to as EIC and VOC, respectively) were concerned that their trade route had secret, deadly rocks somewhere along it. Brookes advised the company to avoid going too far south, theoretically avoiding the Trial Rocks but also reducing speed.

In 1636, the VOC sent a pair of ships under Gerrit Tomaszoon Pool. His instructions included "trying in passing to touch at the Trials," to gather information about their exact location. But he didn't find them.

As the years went on, sailors and mapmakers alike were confused as to where the rocks were and whether they existed. By 1705, the Commodore of the Dutch Ships reportedly didn't believe they were real, at least not in the position Brookes had indicated.

By the late 18th century, even the story's origins were hazy. A 1780 directory of the East Indies claimed that the Trial Rocks were "discovered by a Dutch ship in 1719."

In 1803, English Captain Matthew Flinders took many soundings in the area on his way back from Timor. He spent weeks searching for the rocks despite the fact that illness was rampant aboard ship.

Finally, he concluded that "the Trial Rocks do not lie in the space comprehended between the latitudes 20° 15' and 21° South, and the longitudes 103° 25' and 106° 30' East." Thus concluded, they set sail, hoping to get better food for the sick, as "the diarrhoea on board was gaining ground."

His hard-won findings convinced the British Admiralty, which declared the Trial Rocks nonexistent.

The (re)finding of the Trial Rocks

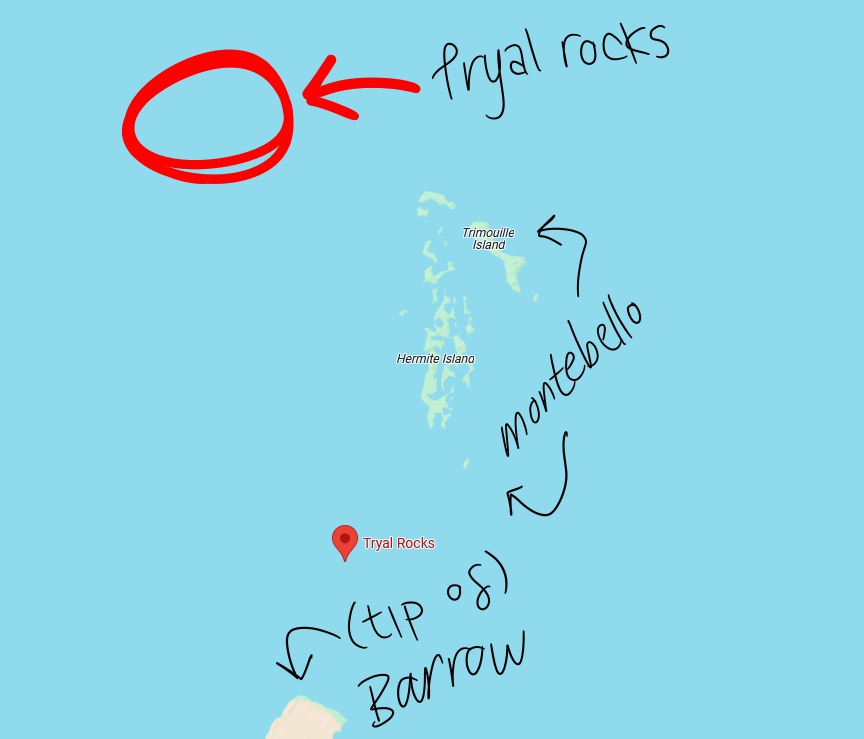

Today, we know that the Trial Rocks lie just off the Montebello Island group, off the coast of Western Australia. The definitive identification of the Trial Rocks came in fits and starts, being repeatedly made and then forgotten.

In 1818, the Greyhound had a run-in with the rocks, managing to avoid being sunk through luck and good spotting. As she was captained by one Thomas Richie, the rocks became known as Richie's Reef. Two years later, another brig passed through the area and had a look-see.

Aboard was Lt. Phillip Parker King, who recorded his belief that the Trial Rocks were, in fact, located around the area of Barrow Island and the Montebello Islands. The next Admiralty chart placed Richie's Reef to the northwest of Montebello, and a second, separate set of Trial Rocks between Montebello and Barrow. They were only wrong by 42 kilometers, which was at least an improvement.

Enter Australian historian Ida Lee. She uncovered the letters by Bright and Brookes and consulted Rupert Gould. Before he became really into the Loch Ness monster, Gould was a member of the Hydrographer's Department at the Admiralty, a respected expert on cartography and naval history.

He replied confidently: Richie's Reef was the Trial Rocks, and Captain Brookes had intentionally deceived everyone about where the rocks lay.

Captain Brookes' great deception

Have you ever really messed up at work? I mean really, really messed up? Imagine if you messed up so bad that nearly a hundred people had died and a huge ship full of valuable trade goods had been lost. Would you lie about it? Be honest.

The truth was that the rocks hadn't been anywhere along the Brouwer route. Brookes had gone too far east, overshooting his turn so badly that they'd sailed right into the coast of Australia. Realizing he went too far, Brookes then headed directly north, instead of northeast, running into the Trial Rocks.

When it came time to write his account, he claimed to have turned earlier and been headed northeast. He told the same lie about the skiff journey, claiming to have traveled northeast instead of east. If he had actually traveled northeast from the Trial Rocks, he would've missed Java entirely.

Brookes had lied about where the rocks were to disguise his mistake, claiming they were hundreds of kilometers west of their actual position. This was not an innocent deception. As the men who died on the Tryall could tell you, knowing where hidden rocks lay was a matter of life and death.

Bright had tried to get the real story out in his letter. But that had been lost to the depths of the archives until Ida Lee. In 1934, Lee published her article, and henceforth, the rocks were placed in the correct location. Except, apparently, on Google Maps, which inexplicably gives the pre-1934 location.

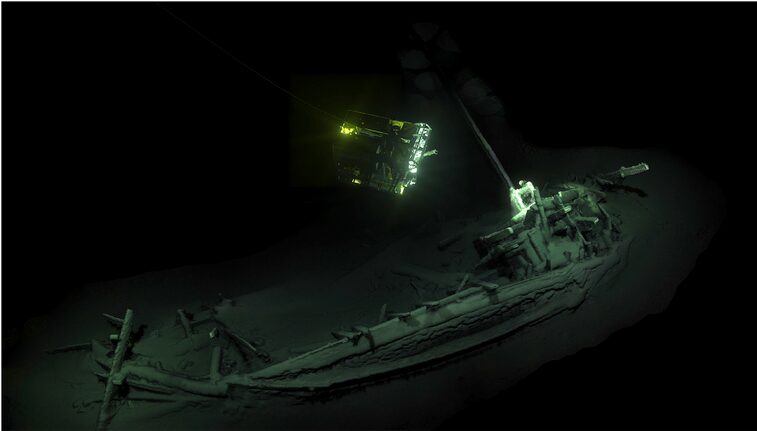

The Tryall gets blown up

No one actually went looking for the wreck until the late 1960s. Two men from a group called the Underwater Explorers Club, John MacPherson and Eric Christiansen, got Gould's report from the Admiralty Hydrographic Office. A few years later, Christiansen led a small party of divers to the wreck site. For our purposes, the most important member of this group was Alan Robinson.

They dove at the Trial Rocks in May 1969. On the southwestern side of the rocks, they found an old anchor, then another, and then cannons — it was a wreck site. They reported the find to the Western Australia Museum and collected a finder's fee equivalent to about $18,500.

The WA Museum organized an expedition, but poor weather prevented them from doing much diving. In 1971, they came back with more funding, but when they dove down to the site, they found it had been vandalized -- with explosives. The reef itself was damaged, along with some of the cannons and anchors, and the various smaller artifacts one would expect around the site were nowhere to be found.

The suspected culprit was Alan Robinson. A notorious figure in Australian maritime archaeology, Robinson was a treasure-hunter who frequently came into conflict with the laws around salvage and cultural artifacts. He was acquitted of the charges regarding the Tryall site, but we'll probably never know the truth.

Robinson died in jail while awaiting trial for attempting to murder his ex-wife, so was unable to confess about using blasting gelatin on Australia's first shipwreck.

An active archaeological site

Several more expeditions visited the damaged wreck site. Like many of the most famous Australian shipwrecks, any write-up of work on the Tryall site must mention the contributions of Dr. Jeremy Green. Green wrote the book on maritime archaeology, and by the discovery of the Tryall, had already led the investigations of the Batavia and Vergulde Draeck.

It was Green who led the 1971 dives and who gave the first tentative identification of the wreck as that of the Tryall. Because of all the missing artifacts, it's difficult to say beyond a shadow of a doubt that the ship found on Trial Rocks is really the Tryall. In addition to the location, Green used the cannons and anchors to confirm that they were looking at the remains of an English merchant ship from the early 17th century.

Subsequent dives have provided further evidence that this is, in fact, the Tryall, such as the makeup of the ballast stones. The most recent expedition took place in 2021, where they confirmed that there were no other wrecks in the area. Since we know that the Tryall wrecked there, and there is only one wreck, it must be the Tryall. After centuries of doubt, we finally have certainty.

The Western Australia Museum recently completed the restoration of one of Tryall's cannons, which is now on display in the museum.

Camera traps in the jungles of Peru have captured footage of ocelots and opossums traveling together. We have at least four confirmed cases of the two animals walking in tandem, seeming to be perfectly aware and comfortable with the other's presence. The pairs were never more than two meters apart, moving at a leisurely pace. Their body language is relaxed, the opossum never attempting its famous "play dead" manoeuvre.

Experts believe that these aren't isolated incidents, but a pattern of behavior. A group of ecologists and researchers released a new study speculating on what that behavior could mean.

Sniff test

Before they developed formal theories, the researchers needed to collect more data. Ocelots might seek out opossums to hunt them, but would opossums actively seek out ocelots?

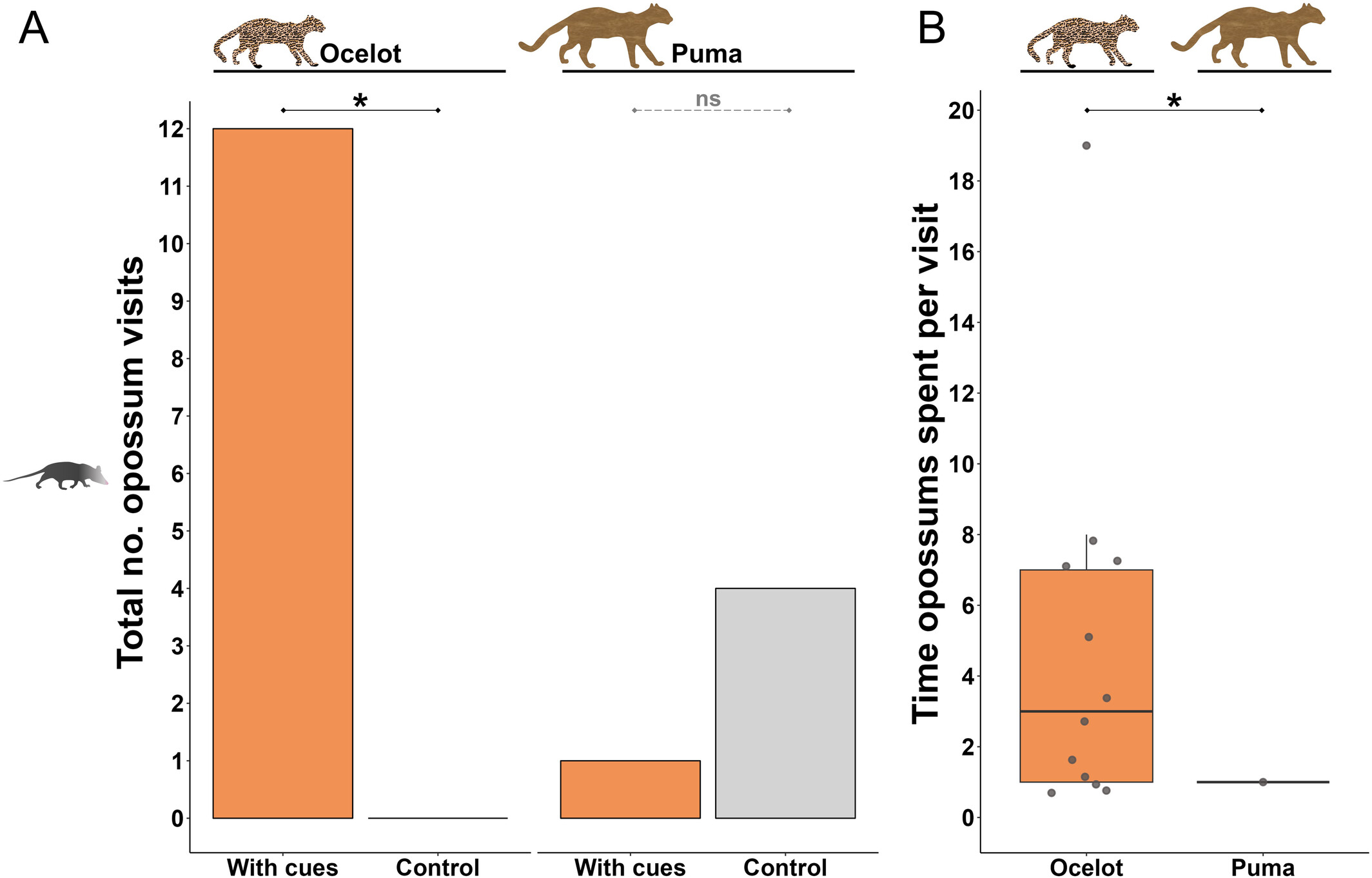

To find out, they set up camera traps with 'ocelot cues' -- items which gave off the scent of an ocelot, usually a strip of fabric -- and waited. Opossums showed up and even interacted with the ocelot cues, sniffing, biting, or rubbing themselves on the fabric. Opossums visited the ocelot-scented cameras far more often than control cameras.

To confirm that it was specifically ocelots that the little marsupials were interested in, they repeated the experiment. Using control and puma (cougar, catamount, mountain lion) scented traps, they observed that the opossums preferred the control, apparently disdaining the company of puma.

Both animals are solitary within their species, yet the ocelot and opossum don't just fall in together, but actively seek each other out. The question remains, why?

Much we don't know

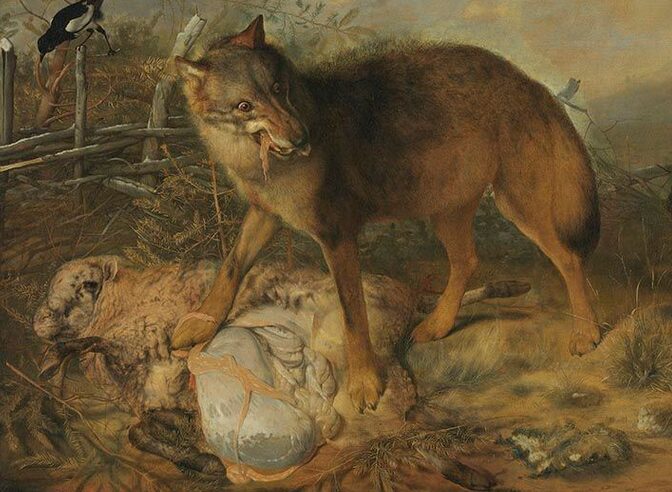

Mutual partnerships between species are not rare and form when both sides have something to offer the other. Coyotes and badgers sometimes partner up to hunt burrowing prey. Their different adaptations and hunting strategies complement each other -- the coyote handles the chasing, and the badger handles the digging.

One theory is that the ocelot and opossum partnerships work much the same way. Opossums often feed on snakes and are even immune to viper venom, like the eponymous hero of Rudyard Kipling's short story Rikki-Tikki-Tavi. Perhaps the pairs team up to hunt serpents.

The researchers also speculate that moving as a pair may be a sort of camouflage. By moving with the notoriously odoriferous opossum, the ocelot could hide its scent, making it easier to stalk prey. Moving with the ocelot, the opossum would be safer from pumas and jaguars.

Ultimately, we don't know if one, both, or neither of these theories is correct. The study concludes with a call for more research, and a reflection on what this find reminds us: "how limited our understanding remains of the complex dynamics among tropical rainforest species."

Like the inverse of the mythical butterfly flapping its wings in China, an ice core extracted from Greenland can reveal the rise and fall of societies in European antiquity. A new study took ice cores from the Greenlandic ice sheet and used them to measure the output of lead pollution in Europe. The varying levels of lead pollution corresponded with technological and societal changes.

A global record

Ice sheets are laid down over time in layers of compacted snow. A bit like tree rings, the conditions during their formation are preserved in the layer.

By taking an ice core, scientists are effectively looking at a timeline of climate conditions over thousands of years. Air temperature, greenhouse gases, pollen levels, and chemical concentrations are printed in the layers.

This latest research is a collaborative effort between several universities and climate research organizations. The ice cores in question come from the North Greenland Ice Core Project, or NorthGRIP. NorthGRIP drilled from surface to bedrock in northern Greenland. While NorthGRIP finished drilling in 2004, the wealth of data it offers is still largely unexplored. Led by Joseph R. McConnell of the Desert Research Institute, researchers recently turned to lead levels.

When we imagine ancient coins, many of us imagine gold, but silver was far more common in most premodern coinage systems. Premodern silver smelting produced a lot of lead pollution, and archaeologists can measure ancient economic productivity through lead levels -- more lead, more coins, more activity.

What your lead poisoning says about you

Wind blows European lead emissions to Greenland, where they freeze in ice. Previous studies worked from limited samples; by using the NorthGRIP ice cores, researchers were finally able to construct a complete record of classical emissions.

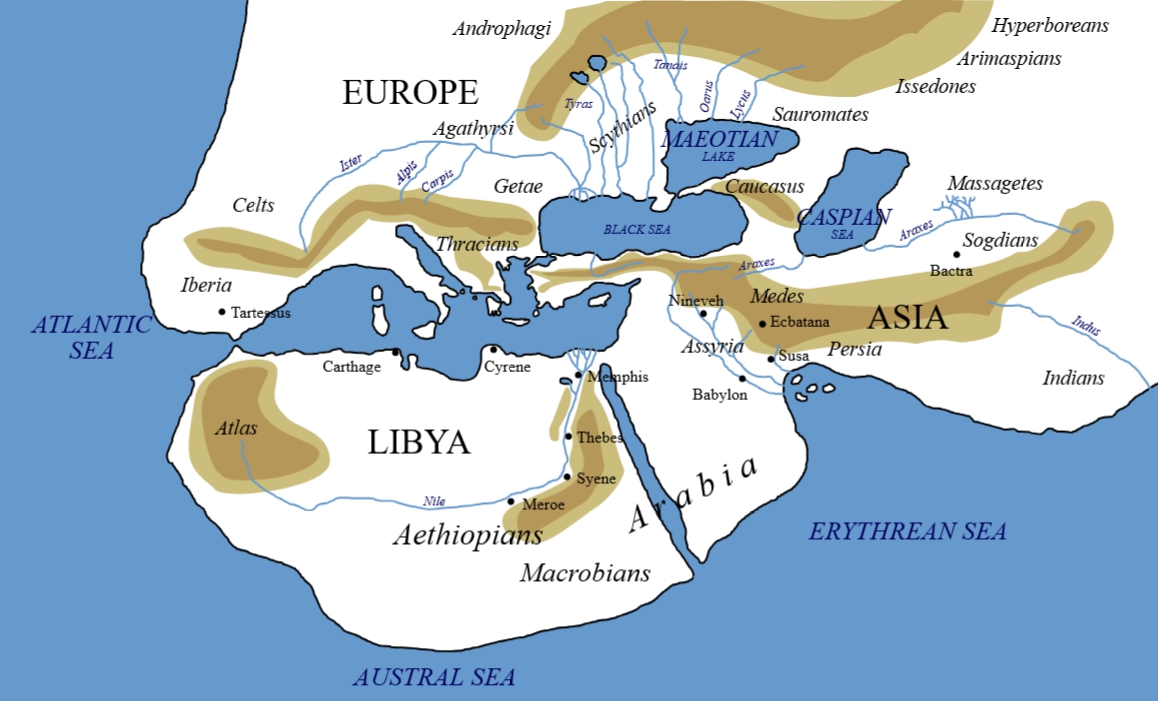

The first jump in lead levels came around 1000 BCE, when the Phoenicians began expanding into the Mediterranean. Emissions continued through the founding of the Roman kingdom and then the Republic. Levels spiked again when both the Romans and Carthaginians colonized Spain and began mining silver intensively there.

Both Punic Wars saw short-term declines, as the campaigning in Spain pulled workers away from the mines and to the battlefields. They bounced back quickly as Rome took Spain and began minting Roman silver coins in Carthaginian mines.

Researchers can chart the whole of Roman history in this way. Wars and political crises lead to dips, and with new conquered territory, mining ramped back up. The peak was the Pax Romana, following the ascendance of Augustus née Octavian.

Putting Edward Gibbon out of a job, the ice cores also document the decline and fall of the empire. "The great Antonine Plague struck the Roman Empire in 165 AD and lasted at least 15 years. The high lead emissions of the Pax Romana ended exactly at that time and didn’t recover until the early Middle Ages, more than 500 years later," explained coauthor Andrew Wilson, of Oxford.

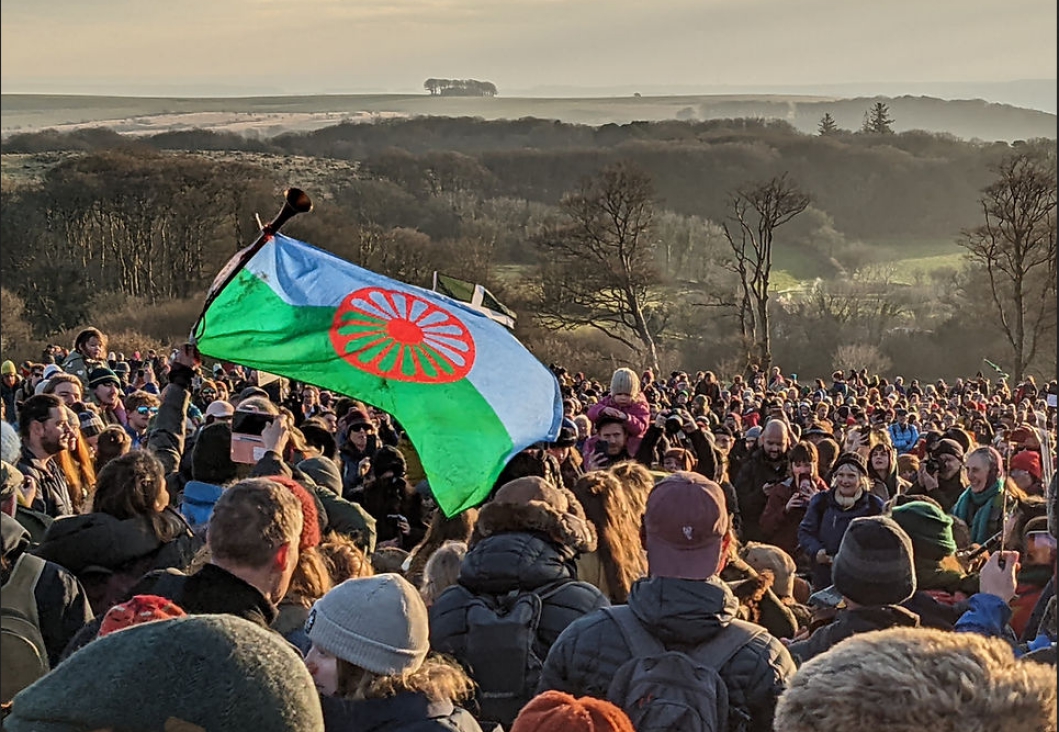

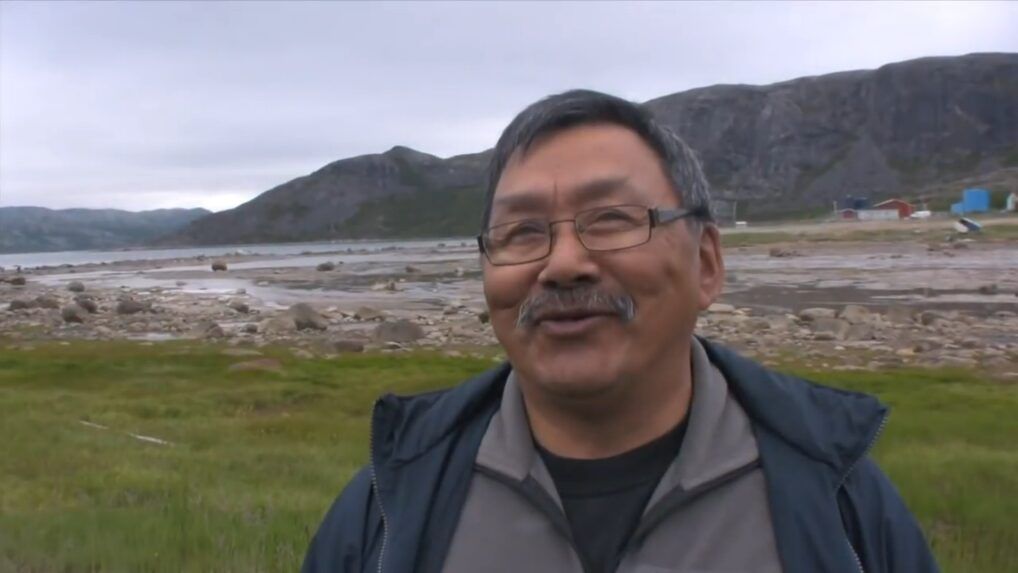

A group of young people from several Native American groups has completed a month-long journey down the Klamath River. The journey commemorates the removal of four dams, leaving much of the river to flow freely for the first time in a century.

Years in the making

Indigenous activists had been fighting for decades by the time the Klamath Basin Restoration Agreement was signed in 2010. The agreement promised to remove the four hydroelectric dams on the Klamath River. In November of 2022, federal approval finally came through for the dam removals.

The first and smallest, Copco No. 2 Dam, was removed in 2023, 98 years after it was built. In 2024, the other three dams -- Iron Gate Dam, Copco No.1 Dam, and JC Boyle -- were removed as well.

Paddle Tribal Waters, a nonprofit program teaching kayak and river advocacy to Indigenous youth from all along the Klamath basin, launched in July 2022. After years of training, 43 young kayakers ranging from 13 to 20 set out on June 12 from the Southern Oregon headwaters. There are still two dams remaining, near the headwaters, which they had to portage around.

The journey took them through canyons with rapids as well as across the choppy Agency Lake and through the dam removal sites. Those who had clearance tackled class 3, 4, and 5 rapids, while others chose to take those sections by raft.

In the last few days, even more young people joined. Youth from indigenous communities in the United States, Chile, Bolivia, and New Zealand took to the water. By July 11, a veritable flotilla, 110 strong, approached the mouth of the river. There, friends, family, and community members waited to welcome them.

A historic return

Now that the river flows freely, the ecosystem is beginning to repair itself. Important species like salmon, steelhead, and lamprey can now access over 600km of historic spawning habitat. The drained reservoirs no longer cause massive algae blooms, so the water quality is increasing and the temperature is decreasing. The speed of the river's recovery is a heartening surprise, even to its staunchest advocates.

"We were hopeful that within a couple of years, we would see salmon return to Southern Oregon. It took the salmon two weeks," said Dave Coffman, in a conversation with CNN. Coffman is the director of northern California and southern Oregon for Resource Environmental Solutions, which is working to restore the Klamath.

Klamath fish populations are a vital resource for Indigenous people along the basin, primarily the Klamath, Shasta, Karuk, Hoopa Valley, and Yurok peoples. But though salmon can now return, they return to a very different habitat. Industrial farming has reshaped and polluted the Klamath, and the federal government has frozen much of the funding for restoration.

The trip wasn't just a celebration, but a commitment to continue the fight. "It’s not just a river trip and it’s not just a descent to us," said Hupa tribal member and Yurok descendant Danielle Frank, a participant who gave a speech at the celebration. "We promise that we will do whatever is necessary to protect our free-flowing river."

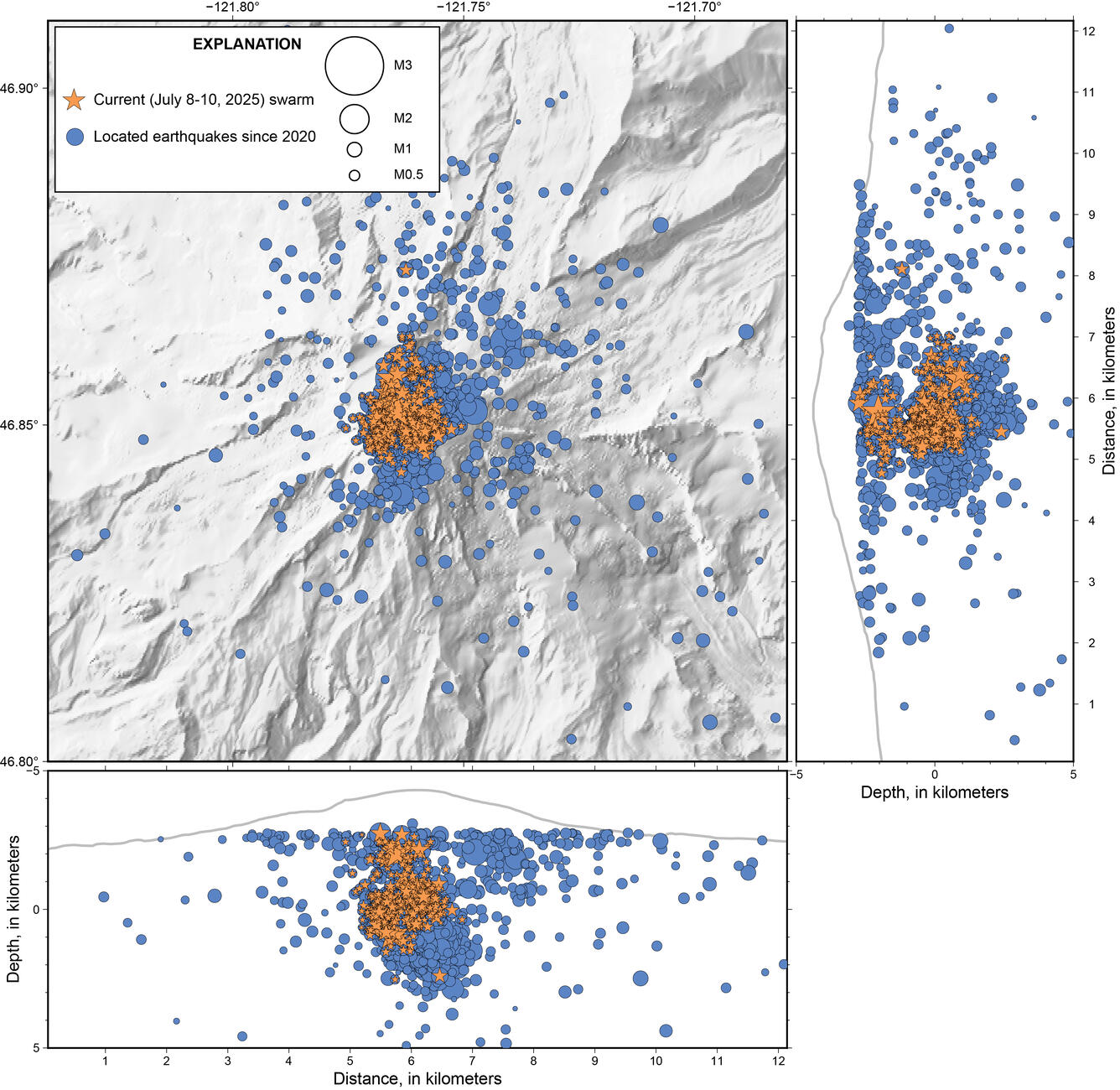

Officials at the United States Geological Survey have tracked over 300 earthquakes beneath Washington State's Mt Rainier from July 8-10.

A popular tourist destination, Mt Rainier is also an active volcano, closely watched by experts. On average, the area experiences nine small earthquakes a month. About once a year, activity will increase and become a "swarm." But these regular annual swarms are not nearly as strong as the current event.

The current swarm kicked off between 1 and 2 in the morning, local time, on July 8. The largest quake came twelve hours later, registering 2.3 on the Richter scale. The strength and frequency of the quakes have steadily decreased since. The Pacific Northwest Seismic Network continues to track the miniature earthquakes.

Much stronger than the 2009 swarm

The 2025 event has far outstripped the most recent big swarm, from 2009. Scientists detected 120 earthquakes in 2009, and the current swarm is approaching 350, at least 55 of which have been over 1.0 magnitude.

However, officials aren't concerned yet. The volcano alert level remains at "Green/Normal," with no danger to hikers. None of the earthquakes, individually, has been big enough to cause any damage, or even felt by visitors to the mountain.

Volcanic disruption is far from the only cause of seismic activity. Rockfalls and landslides can register as seismic events. Glacial movement is another potential contributor, especially since Mt Rainier is the most glaciated peak in the lower 48. Officials believe the recent activity is the result of water moving through preexisting fault lines, above the magma in Mt Rainier.

Just because this level of activity is higher than what we've previously observed doesn't mean it's abnormal. "We've only been monitoring it for 40, maybe 50 years now. So just because it's the most significant one we've seen on equipment doesn't mean this hasn't happened in the past," cautioned Alex Iezzi, a geophysicist with the Cascades Volcano Observatory.

The previous eruption of Rainier was over one thousand years ago; we have a limited understanding of what normal looks like. From that perspective, the swarm is good. It will give researchers an opportunity to learn more about how the volcano works and what we can expect it to do in the future.

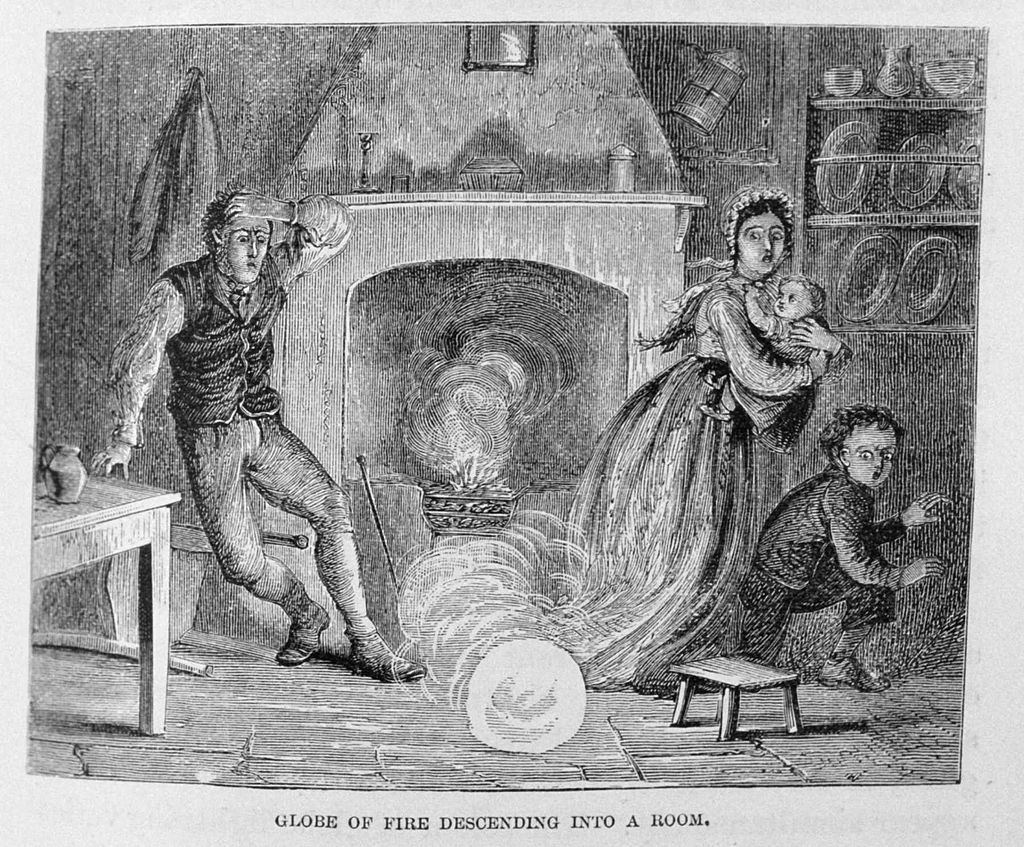

As a massive storm swept through central Alberta in early July, a couple stood on their porch watching bolts of lightning play across the cloudy skies. A particularly massive lightning strike hit nearby. A moment later, they saw a ball of light hovering near the impact site.

In an interview with Global News Canada, Ed Pardy described seeing "a ball of fire… about 20 feet above the ground, and it kind of stayed there in a big round ball."

Ed and his wife, Melinda, said the orb consisted of bluish light, maybe two meters across. Amazed, they began filming. The couple captured 23 seconds of the light hovering on the horizon, before it vanished with a popping sound.

After viewing the video, that the couple sent to several Canadian news networks, many people believe the phenomenon is "ball lightning."

Elusive and mysterious

Ball lightning is a rare and little-understood atmospheric phenomenon. Accounts vary, but the generally agreed-upon description is of a ball of light, anywhere from a few centimeters to a few meters across. Ball lightning coincides with thunderstorms and hovers for a minute or so before disappearing.

Accounts of ball lightning are uncommon, but stories have been around for centuries. The earliest account commonly cited is from a massive storm that swept over England in 1638. Three hundred people were attending church when, according to eyewitness accounts, a ball of fire over two meters across burst through the church window, bashed around, tore open the roof, and killed four church-goers, filling the building with smoke and the smell of sulfur. Witnesses concluded it was the devil, an understandable conclusion at the time.

This isn't the only story of "globular lightning" entering a building. In 1852, the French Academy of Sciences took sworn statements that a ball of light, roughly the size of a human head, burst from the fireplace of a startled tailor, having traveled down the chimney.

In 1753, ball lightning killed a Russian scientist researching electricity, according to contemporary reports. Georg Richmann was holding one end of a string, the other end of which he had attached to a kite. Ball lightning appeared, traveled down the string, and killed Richmann instantly.

Despite scattered reports continuing over the years, scientific understanding lagged behind.

Many theories, limited evidence

So, what exactly is ball lightning? Science isn't quite sure yet. Many reports can likely be attributed to other things. A 2010 study from researchers at Austria's University of Innsbruck found that the magnetic fields generated by lightning storms could cause visual hallucinations. Specifically, they can cause "magnetophosphenes," which appear as flashing lights. This could account for cases of ball lightning.

But unless magnetophosphenes are contagious and spread over video, what the Pardy's saw was real.

Researchers have put forward dozens of theories to explain ball lightning. One of the more credible theories came from a group of Chinese researchers who happened to record ball lightning in 2014. In only a few seconds, the ball went from purple, to orange, to white, to red and then sputtered out. The changing colors indicated its makeup, and the scientists detected small amounts of silicon, iron, and calcium.

They proposed that ball lightning forms when a lightning bolt hits soil, vaporizing the elements within, and creating light and color effects. Experiments in 2007 using vaporized silicon support this theory. Scientists from the Federal University of Pernambuco were able to produce small glowing orbs by delivering electric shocks to silicon wafers.

Another theory is that ball lightning is detached Saint Elmo's fire (a faint light on the extremities of pointed objects during stormy weather, such as around the masts of ships). There's also the "Electrochemical Model," positing that ball lightning is air plasma held in a ball by layers of chemical ions.

Science has yet to settle which, if any, of these theories is correct. But the video filmed by the Pardy's is probably the best video of ball lightning captured so far, and lightning phenomena researchers will likely pore over the 23 seconds of footage for new information.

Nineteen-year-old Darcy Deefholts went out surfing on the afternoon of July 9 at Wooli Beach in New South Wales, Australia. When he failed to come home that night, his parents raised the alarm, calling the police to report the young man missing. Authorities immediately launched a large search-and-rescue effort.

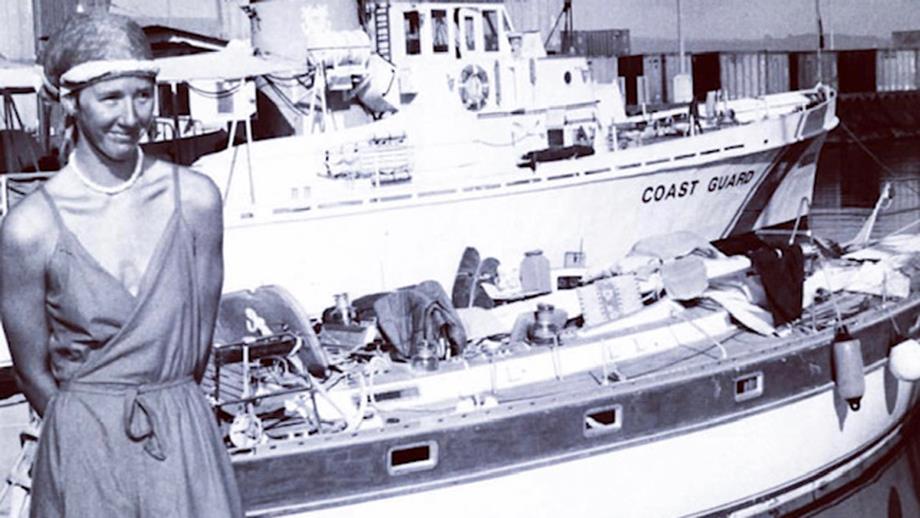

Searchers found his discarded clothes, shoes, and bicycle on the beach. It was obvious that southward currents had swept the young man out to sea. The only source of hope was the absence of his long board. Marine Rescue New South Wales assembled a crew of volunteers and launched their rescue boat, Wooli 30. The community rallied, adding half a dozen private vessels to the search efforts.

Water conditions were favorable, and they were able to cover a significant stretch of coast. But at 1 am on July 10, the vessel had to return to shore, unsuccessful.

One in a million

On the morning of July 10, SAR operations recommenced. Wooli 30 and six other boats began searching, while many more volunteers canvassed the beaches. Around 9 am, a crew of volunteers, including the missing man's uncle, found him alive on North Solitary Island.

North Solitary Island is part of the Solitary Islands, named by Captain James Cook when he sailed past them in 1770. The small uninhabited island lies 14 kilometers off Wooli Beach.

Deefholts spent the night adrift, clinging to his longboard, before reaching the relative safety of the island. When searchers found the missing surfer, he was cold and suffering from exposure, but otherwise uninjured. Upon reaching shore, he was taken to Grafton Base Hospital for medical assessment and is reportedly recovering well from his ordeal.

His father, Terry Deefholts, spoke with the Australian Broadcasting Corporation, expressing his relief and amazement that his son had been found. He had been close to giving up, he told them. "It's a one in a million. Who survives this?"

ABC also spoke with Marine Rescue Wooli Unit Commander Matthew McLennan, who led the group that found Darcy Deefholts.

"It's rare that we ever get to participate in a search with an outcome such as this," McLennan said. The massive community response, and the happy resolution to a case everyone expected to end in tragedy, was "really heartwarming."

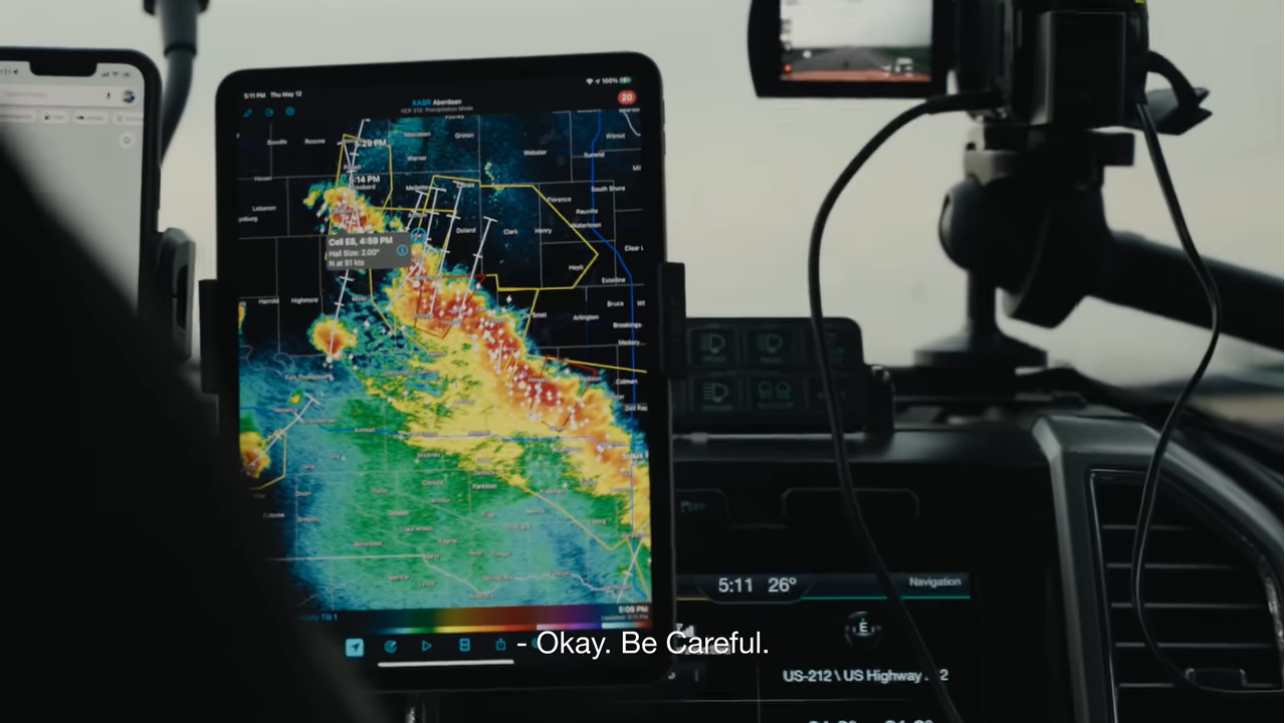

In Tornado Hunting: Chase it From the South, storm chasers Chris Chittick and Ricky Forbes document their lives in the notorious Tornado Alley of the central U.S.

Just south of Sioux Falls, North Dakota, Forbes, Chittick, and their crew are waiting and watching the skies for funnels of violent cloud.

"We are in the right spot!" they crow as a tornado warning comes in only a few kilometers away. The tornado siren echoes through an empty town as dark clouds roll overhead. The unfolding scene is apocalyptic. The air turns green, they lose signal -- but the tornado doesn't appear.

A professional storm chaser is like a sailor of old. The wind and weather are the ultimate deciders of success, no matter their skill or determination. Like the tars, they spend a lot of time away from their families.

After the disappointing storm, in a rain-soaked parking lot, Chris calls home and tells his children that he misses them. Then it's back on the road.

Home is Saskatchewan, Canada. Chris pushes one of his three young children on the swing, one eye on the darkening sky.

"I feel like weather always wins," admits his wife, Chelsea.

Meanwhile, Rickey and his fiancée, Tirzah Cooper, are driving to her first cancer treatment. She wonders how soon she'll lose her hair.

From the south

A storm is forming around Canby, Minnesota, and the Tornado Hunters drive to meet it. But the road conditions and local terrain complicate their attempt. Hills and tall trees prevent their view and access to the storm. The only chance of getting close is to go right in front of the storm's path, a dangerous gamble. It's safer to approach tornadoes from the south, as the storms move in a northerly direction. Driving into them head-on can, and has, been deadly.

"The more I've storm-chased, and the more that I've seen the destruction that tornadoes can do, the more terrified I become of them," admits Ricky.

They're watching construction crews haul away the wreckage of a ruined house, after the storm they failed to catch has passed.

Their caution brings them back to Saskatchewan, where Ricky and Tirzah go to another appointment. He shaves her head. Not long after, a nearby tornado watch offers what he thinks will be the best chance all year. She urges him to chase after it.

After a succession of near-misses, Ricky finally approaches a dramatic tornado. He stops the car and stands in the road, staring up at the twisting mass dominating the sky. In narration, he says that the feeling he had at that moment was the same feeling of awe he experienced the first time he saw a tornado.

Then, he goes home. " A few years ago," he says, "I never thought anything could be more important than storm chasing. I was wrong."

The film ends with him at home, as on-screen text tells us that both Ricky and Chris continue tornado hunting, and Tirzah is now cancer-free.

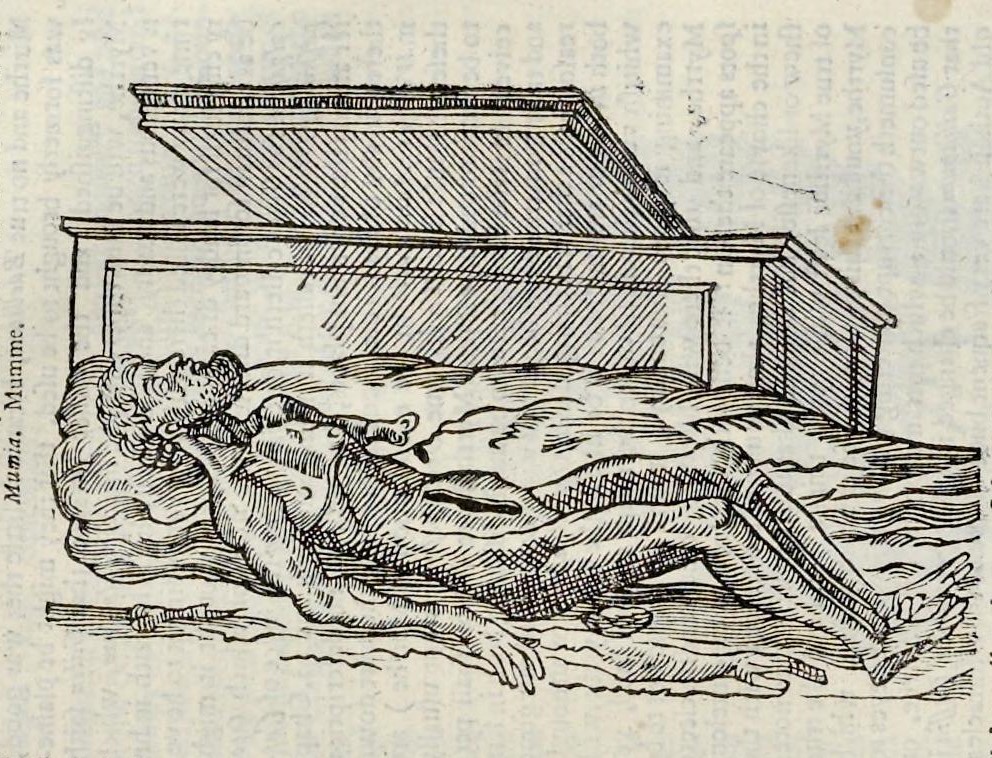

While Egyptian kings and queens are the most famous examples of mummification, the practice wasn’t just for pharaohs. It expanded over time until everyone from the poor up were being preserved for eternity.

So, where are all the mummies? Well, unfortunately, 700 years of rich Europeans ate them. For their health, of course.

From a 12th-century translation error, a massive trade kicked off, depopulating the tombs of Egypt to populate European apothecaries -– and starting an underground market in fake mummy powder.

Bitumen and mūmiyah

Why did Europeans think that eating mummies was a good idea? It's all to do with bitumen. Bitumen is a viscous petroleum product, which occurs naturally in a semi-solid form. Bitumen is particularly common around the Dead Sea, and is useful for waterproofing and as a glue. Archaeological evidence shows that both early humans and their Neanderthal cousins used bitumen tens of thousands of years ago. It even appears in the Bible as the mortar which was used in the tower of Babel.

By the classical era, bitumen was used in everything from shipbuilding to jewelry. People also started using it as medicine. Pliny the Elder, a Roman author and naturalist, lists 27 discrete medicinal applications for it. These include staunching blood flow, diagnosing epilepsy, treating leprosy, dysentery, and gout, and curing toothache.

After the fall of the Roman Empire, Muslim scholars took pains to preserve classical learning. By the Middle Ages, Arabic authors were considered the foremost medicinal experts throughout Europe and the Middle East. The tradition of using bitumen as medicine continued through the works of scholars like Avicenna, who prescribed it for concussions, paralysis, and more. He didn't call it "bitumen," though. He called it mūmiyah, from the Persian word mum, meaning wax.

A medieval game of telephone

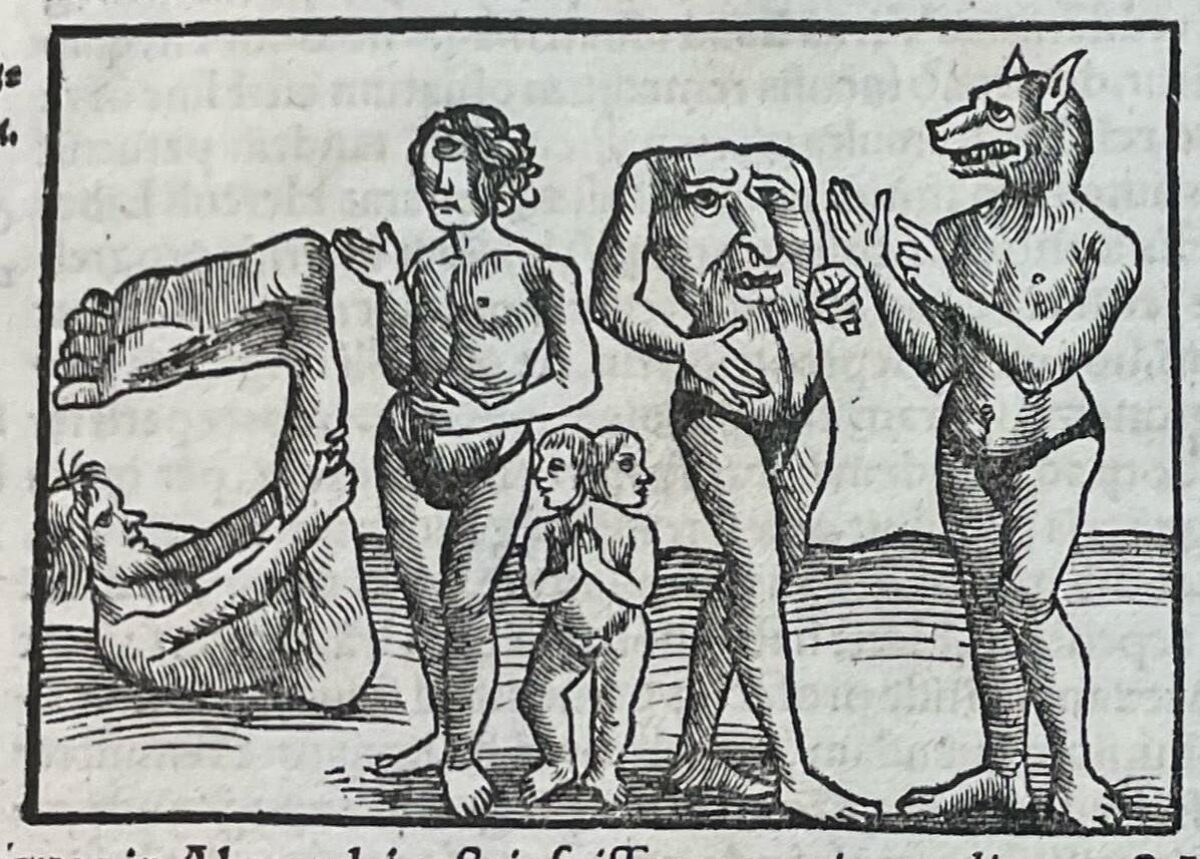

The Ancient Egyptians didn't use bitumen for their mummies. However, the dark resin they used resembled bitumen, leading many classical and medieval observers to believe that bitumen coated Egyptian mummies. So the same word came to refer both to naturally occurring bitumen and the dark waxy coating found on Egyptian mummies.

In the 12th century, an Italian translator of Arabic texts named Gerard of Cremona came across Rhazes of Baghdad's reference to mūmiyah. Gerard said the product was created when "the liquid of the dead, mixed with the aloes, is transformed and is similar to marine pitch.”

Another European, Simon Geneunsis, translated a work by Arab physician Serapion the Younger that referenced medicinal bitumen as "mumia." Geneunsis interprets the word along the same lines as Gerard of Cremona, calling it "the mumia of the sepulchers," which is formed when the aloes and spices used to prepare the dead mix with the liquids the corpse itself expels."

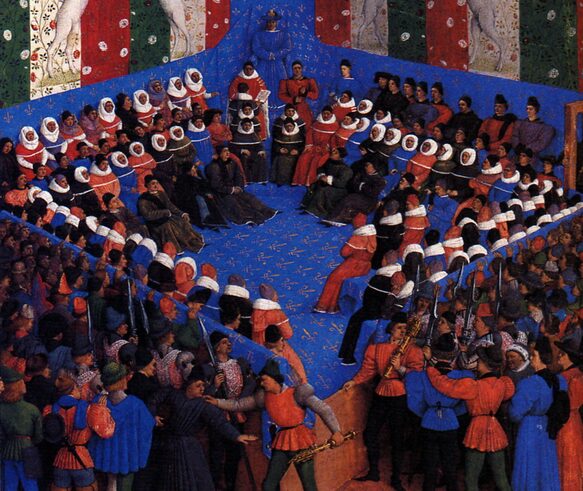

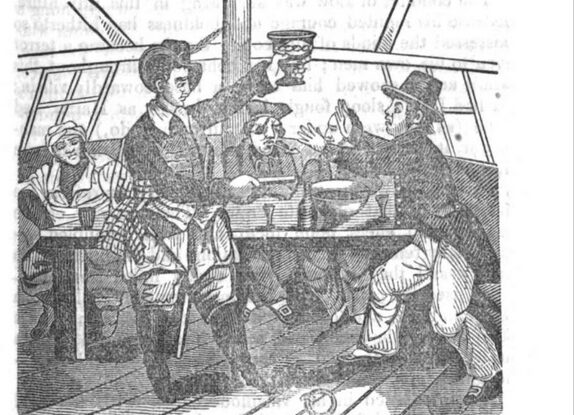

Meanwhile, crusaders were bringing back the bitumen medicine fad from the Islamic medical traditions of the Middle East. Unfortunately, the easily accessible supplies of bitumen in the area were limited. Shrewd Alexandrian merchants realized that there was all this mumia lying around, coating the bodies of the dead. They began raiding tombs, breaking the resinous bodies up, and exporting them to Europe.

The fact that the mumia came from corpses didn't bother people much, possibly due to the confusion between medical mumia and Egyptian mummies. Before long, mumia stopped being the substance on the mummy and became the mummy itself.

It's good for what ails you

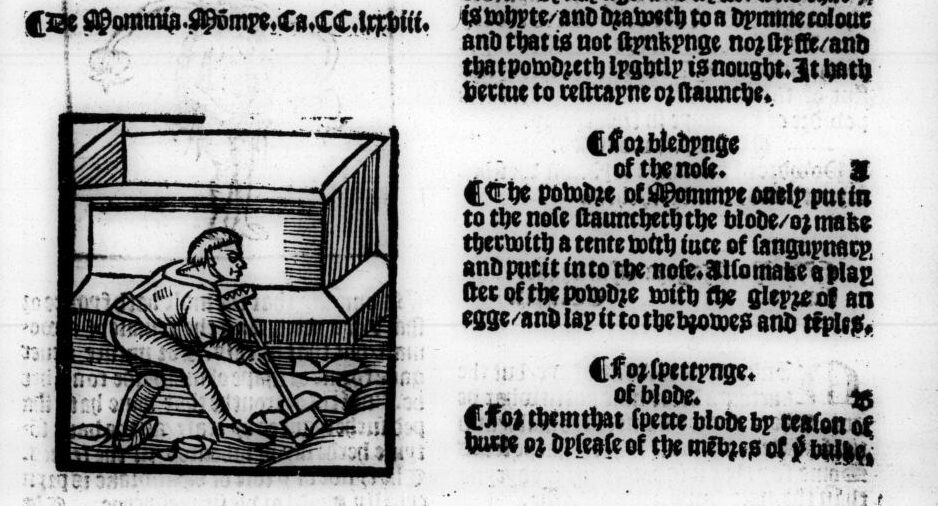

Mumia became a wildly popular remedy in Europe, sold in every well-stocked apothecary. One influential pharmacopeia, Theatrum Botanicum, contains a long list of conditions mumia is useful for, including headaches, colds, coughs, seizures, heart problems, poisoning, scorpion stings, snake bites, bladder ulcers, paralysis, and retention of urine. Treatments involved combining mumia with other ingredients, usually a liquid like wine or goat milk.

Genoese physician Giovanni da Vigo considered mumia an essential medicine for ship's physicians and village doctors. He claimed it promoted wound healing and staunched bleeding. Sir Francis Bacon, the eminent English philosopher, and the physicist Robert Boyle, both considered it useful for wounds, falls, and bruises.

The French king, Francis I, was a habitual mummy consumer; contemporaries reported that he always carried a mixture of rhubarb and mumia on his person, just in case. Nicasius Le Febre, chemist to England's King Charles II, recommended mummy from Libya specifically.

By the way, if you were wondering how it tasted, the English College of Physicians has the answer. Mummy was listed in their official pharmacopeia from 1618 to 1747, where it is described as being "somewhat acrid and bitterish."

Supply chain issues

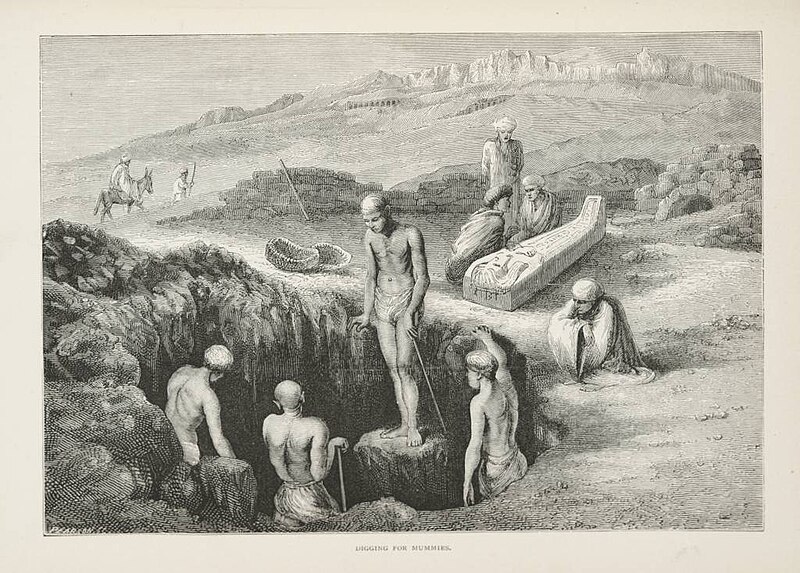

Egyptian authorities were not actually keen on all the grave robbing and corpse exporting that was happening. In 1428, authorities in Cairo captured and tortured several people connected to a mummy scheme. They confessed to robbing tombs, boiling the mummified bodies in a pot, and selling the oil which rose to the surface.

It was illegal to export Egyptian mummies out of Egypt. But enforcement could be lax, especially if you had money to grease the wheels. Englishman John Sanderson visited Egypt in 1586, where he explored a sepulcher and broke off chunks of blackened mummified flesh. He applied the correct bribes and compliments, and sailed off with 600 pounds worth of "divers heads, hands, arms, and feete."

For every literal boatload of real pillaged mummies, there was at least an equal measure of mummies created specifically for export. Many mummy sellers in Egypt found it was easier to source fresh corpses and dry them than it was to dig up old ones. These fresh corpses mostly came from executed criminals, plague victims, and enslaved people.

The Italian traveler Ludovico di Varthema wrote about the local production of mumia during a visit to the Arabian Peninsula. According to him, there were two kinds; the first was made from the dried-up remains of people who had died recently while crossing the desert. The other, nobler and more pure kind, was "the dryed and embalmed bodies of kynges and princes."

In truth, even authentic mumia wasn't made from rulers, but from their subjects. European nobles liked to imagine their healthful powder came from ancient priestesses and kings, but the remains of the poor were far more plentiful and accessible.

Paracelsus and domestic mummy manufacture

Though a fair amount of the mummy product on the market was inauthentic, the real stuff was still being sold into the modern era. One recent study analyzed the contents of an 18th-century pharmaceutical jar labelled "mumia." They found that the contents really were the remains of an Egyptian mummy from the Ptolemaic period.

But without our modern analysis tools, the question of mumia authenticity was an ongoing problem for physicians. As the supply became more questionable, some medical authorities began to wonder whether mumia being "authentically Egyptian" was even important.

Some definitions of mumia dropped the ancient Egyptian element entirely, ascribing benefits to any old preserved human flesh. The influential physician Paracelsus, who spawned a legion of followers, believed the medicinal benefit of mumia came from a transfer of life energy. To make his mumia, he left a fresh body out exposed. The best bodies were of young, healthy men who died suddenly. Other recipes in this line were even more specific, preferring a 24-year-old redheaded man who was recently executed.

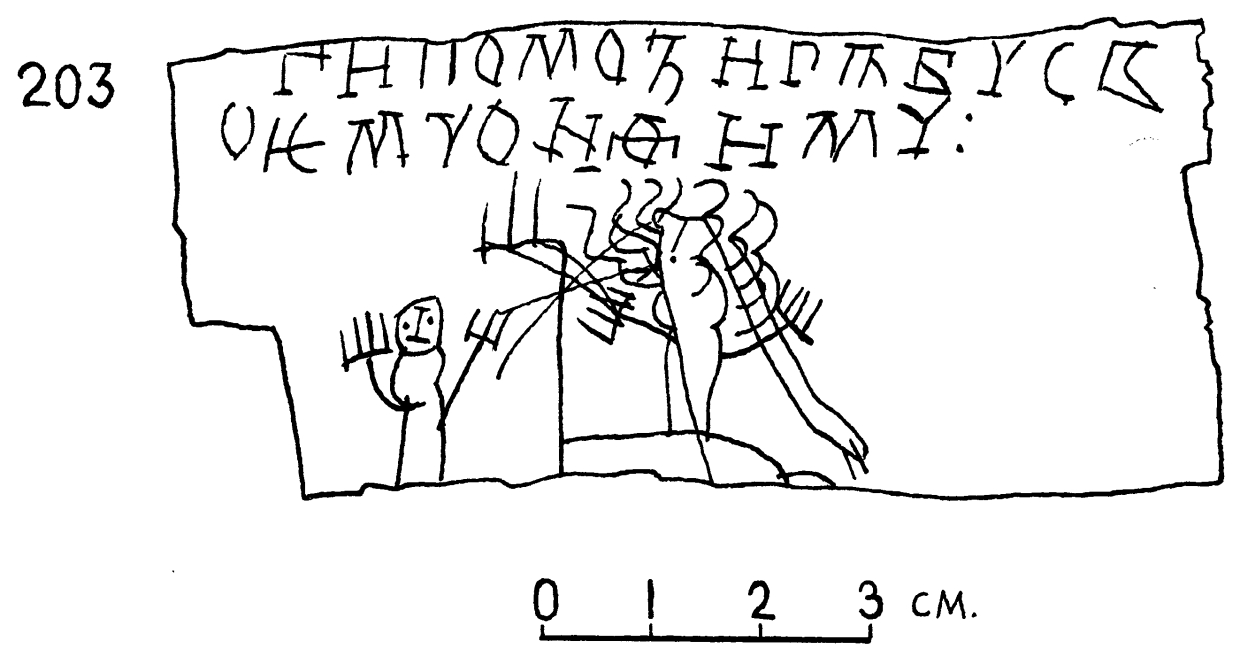

There was a persistent belief that there was a vital animating force remaining in corpses, and one could benefit from this force by consuming corpse products. In the time of Paracelsus, for instance, executioners would collect and sell the blood of those they executed. People believed that drinking it promoted general health and cured epilepsy. Bandages soaked in human fat were applied to wounds, and powdered human skull was prescribed for headaches.

The broader genre of corpse medicine is beyond the scope of this article, but suffice it to say that mumia wasn't always the only human-derived medicine available.

Some reasonable concerns

Now I'm not a doctor, but I feel confident in saying that "you should eat powdered human corpses for nosebleeds" is not best practice. By the 16th century, many doctors were starting to think along the same lines.

Ambroise Pare, surgeon to four French kings, published a 1582 treatise decrying the use of mummy. He argued that most mummy sold was actually manufactured in France from the recently dead, and also didn't work. In his professional experience, it had not only failed to stop bleeding but had unsurprisingly caused the patient to have an upset stomach and bad breath.

Pare's German contemporary, Leonhart Fuchs, made similar arguments. He also laid out the series of medieval translation errors which had led to the idea of mumia. Fuchs decried the "stupid...credulity of certain doctors of our age," who still prescribed mummy.

Additionally, some commentators were beginning to recognize the historical and cultural wealth that was being ground up for tinctures. English natural philosopher Thomas Browne opined that "The Ægyptian Mummies, which Cambyses or time hath spared, avarice now consumeth. Mummy is become merchandise, Mizraim cures wounds, and Pharaoh is sold for balsams."

There was also cannibalism. Michel de Montaigne, a 16th-century French writer and early critic of colonialism, pointed out the hypocrisy of demonizing cannibalistic practices in the New World while taking medicinal human flesh at home. But most people didn't think of it as cannibalism, any more than people today would consider a blood transfusion cannibalism. Mumia wasn't food, it was medicine.

Still, as time went on, people were increasingly wondering if it was medicine they should be taking. Mumia mania peaked in the 18th century, but took much longer to fade entirely.

Consuming Egypt

For wealthy Europeans, part of the appeal of mumia was the mystical, exotic associations. For centuries, Europeans treated the bodies of deceased Egyptians with a combination of fetishistic fascination and blatant disrespect. They were curios and collectors' items, souvenirs of exciting trips turned household decor.

Mummy unwrapping parties were popular in 19th-century Europe, where middle and upper-class men and women would watch a mummy's bandages be unwound, revealing its body as the finale of the morbid show.

The remains were consumable as a variety of commercial products. A popular paint color from the mid-18th to 19th centuries was "mummy brown." This pigment was made from ground-up mummified bodies. Art historians believe this rich, warm brown pigment appears in a number of well-known paintings, including Eugene Delacroix's famous Liberty Leading the People. The last tube of mummy brown was produced, unbelievably, in 1964.

There are also accounts, of varying reliability, that both human and animal mummies were used as fertilizer, paper (from their bandages), and fuel for locomotives. These claims are likely exaggerated, but they speak to the manner in which mummified Egyptian remains were treated at the time. As Imperial plunder, they were, literally, things to be consumed.

The end of the mummy-eating era?

By the end of the Victorian period, mumia had fallen out of popular use. But it was still available for sale, and occasionally prescribed, into the beginning of the 20th century. The last known appearance of the drug for sale is in a 1908 Merck catalogue. The German pharmaceutical advertised, "Genuine Egyptian mummy as long as the supply lasts, 17 marks 50 per kilogram."

Rich old Europeans didn't actually eat up all the mummies. Archaeologists are still finding them, for one. It's impossible to say how significantly the manufacture of mumia impacted the number of surviving mummified remains. It's safe to say, though, that nearly a millennium of looting Egypt led to the loss of untold historical and cultural knowledge.

The 1908 example is troublingly recent, but we might still be tempted to dismiss mumia as something from another, less enlightened age. Exporting ground-up mummy to eat as a health supplement is something so patently absurd that a modern reader might make the mistake of smugly holding themselves above all those involved in the practice.

It's true that we don't eat mummies anymore. But physical and cultural wealth is still extracted from exploited nations for the consumption of the global north.

Most human bones available for sale in the West, as curios or medical teaching tools, come from India, though the export of human skeletons was officially banned in the 1980s. World-class museums still display cultural artifacts and remains of colonized people for the predominantly white public to gawk at. Mummy remains merchandise.

Around 3:30 pm on July 2, an SOS signal from a Garmin InReach device reached the California Governor’s Office of Emergency Services. It had been sent from just below the summit of 4,383m Mt. Williamson, the second-highest peak in the Sierra Nevada.

The sender, whose name authorities have not released, had fallen and sustained serious injuries. She also lost most of her equipment. Her situation soon became even more desperate when a thunderstorm rolled in. Lightning menaced her, and lashing rain beat over the area as a multi-agency rescue operation launched. But the weather, her severe injuries, and the difficult location kept her stranded for many hours.

The woman had been scrambling off-route near the West Chute on Mt. Williamson. While snow-free in July, the nearly 500m chute has sections of loose scree which make it difficult. Mt. Williamson is trickier to summit than the slightly taller Mt Whitney. There is no established trail above 3,000m, and there aren't many fellow climbers around.

The woman was just a few hundred meters from the summit when she fell, losing her backpack and badly breaking her leg. Over her Garmin, she described the grisly compound fracture -- a fracture where the bone protrudes through the skin -- and her lack of food, water, and extra clothing.

A series of helicopter attempts

California Highway Patrol sent an Airbus H125 helicopter to pick up rescue volunteers. By the time rescuers were on board, the storm had fully descended, bringing cloud cover that prevented the helicopter from reaching her.

More resources were called in, and the nearby China Lake Naval Air Weapons Station agreed to lend aid. They transported search-and-rescue workers to Shepherd's Pass, around 3,000m up, but couldn't get any closer. This was around midnight. Volunteers proceeded on foot, reaching the bottom of the west face by sunrise.

They were able to call up to the stranded climber, but the terrain prevented them from reaching her. By then, however, the weather had improved somewhat, and the helicopter returned and dropped two rescuers about 100m above her. They carefully made their way down, reaching her 23 hours after her fall.

They still had to get her out. Again, SAR personnel called in more resources. The Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department's Air 5 helicopter buzzed over, but the elevation proved too much. Finally, the California National Guard offered their Blackhawk Spartan 164.

SAR workers on the ground carefully moved her into a more open position. Just after 7 pm on July 3, 28 hours after her fall, she was hoisted aboard Spartan 164 and eventually transferred to a hospital.

According to a statement from Inyo County Search and Rescue, the victim displayed "Enormous bravery and fortitude...and all involved were impressed by her ability to remain calm, collected, and alive."

Perhaps the most famous ship in exploration history, the Fram was designed specifically for the challenges of polar navigation. With her rounded hull, she withstood the crushing ice that shattered the likes of Shackleton's Endurance, rising up over the ice instead of being pinned by it. Her design, however, which made her so perfectly adapted to her line of work, also made her roll horribly in the open sea, inducing seasickness.

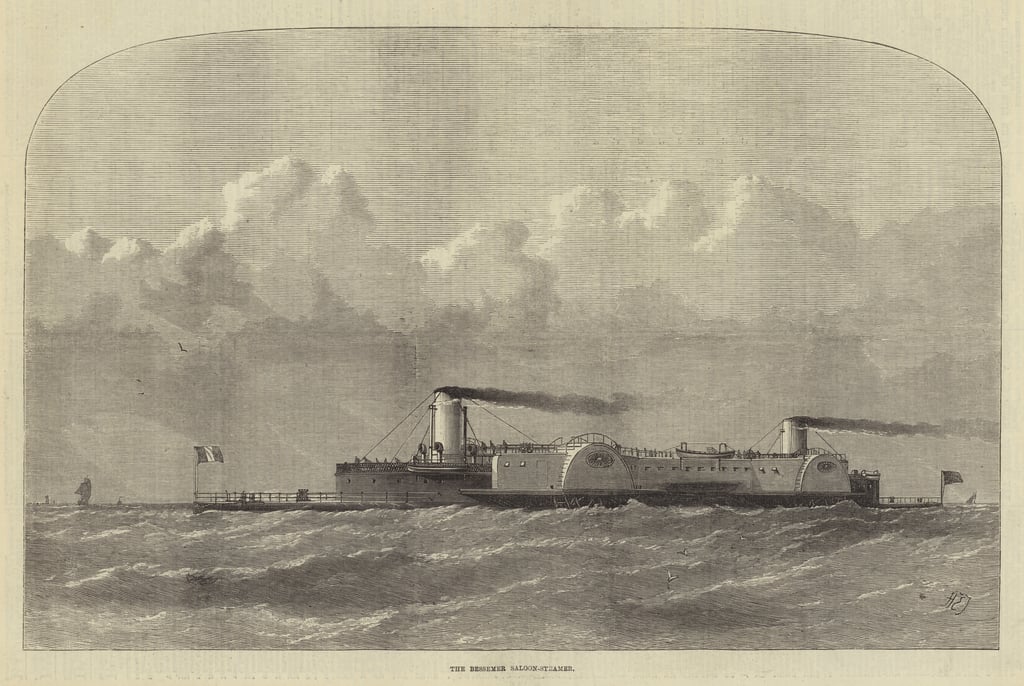

The SS Bessemer was basically the exact opposite of the Fram. While she was engineered against seasickness, she also seemed to be engineered against seaworthiness. Or perhaps some jealous oceanic deity, seeing humanity attempt to conquer the limitations he'd placed upon their encroachment in his domain, cursed the poor ship.

Cursed or no, the SS Bessemer certainly had an eventful career.

The eponymous Bessemer

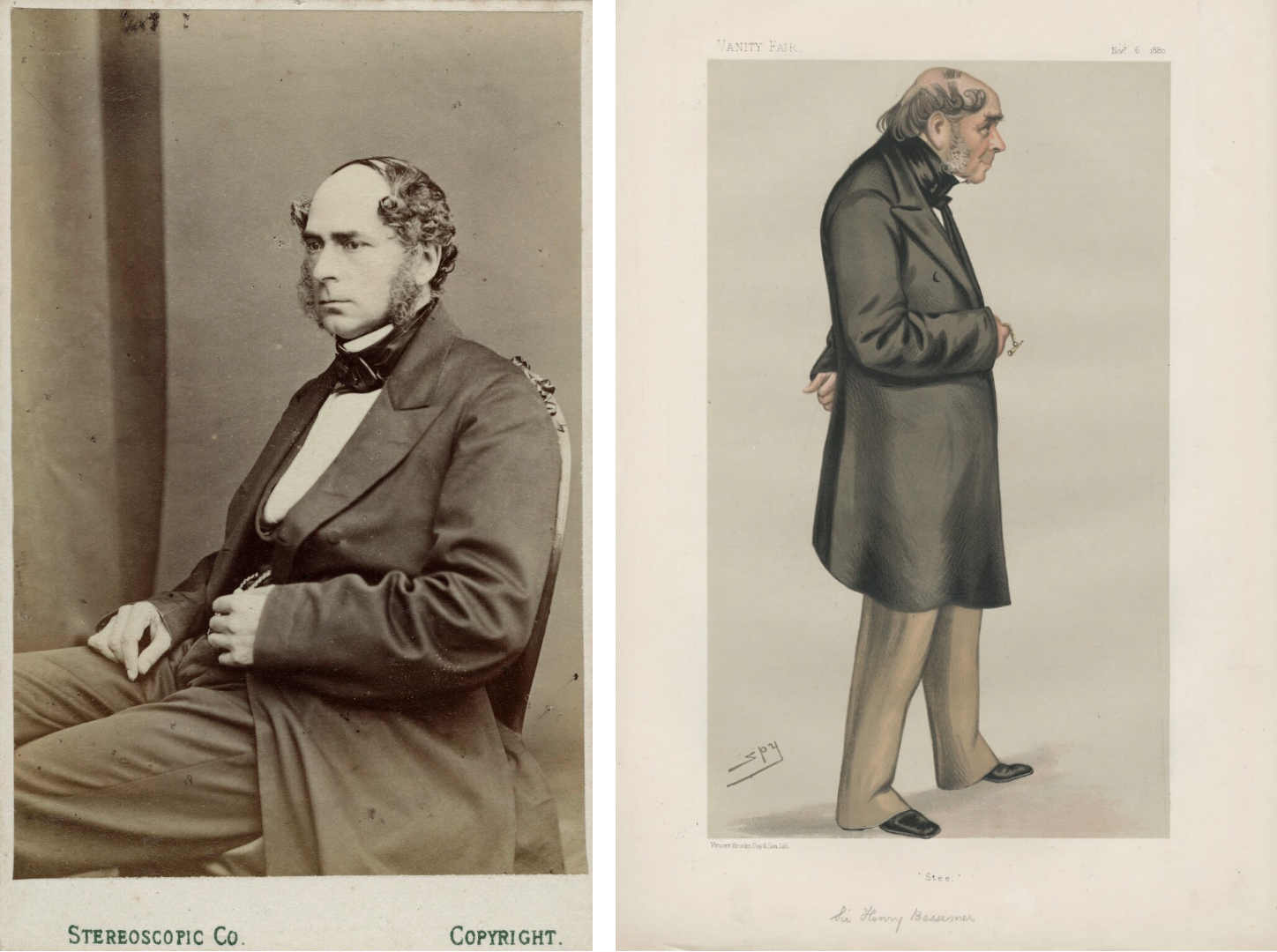

Henry Bessemer was born in 1813 on his Huguenot inventor father's small Hertfordshire estate. After fleeing the French Revolution, his father settled in England and made his money from his inventions. Henry took after his father, fascinated by machinery and driven to improve upon the mechanisms he observed. He moved to London at 17 to seek his fortune and immediately began experimenting.

His first big success was a steam-powered machine to manufacture bronze powder. Originally, his only ambition with the experiment was to make gold paint for his sister, a watercolor artist. But the process and manufacturing machines he developed made enough to support him while he continued inventing.

If you've heard the name Bessemer, you've heard it in connection with his most important invention: the Bessemer process. In terms of Industrial Revolution inventions, it ranks among the steam engine, the telegraph, and the spinning jenny.

What Bessemer invented was the first way to produce steel quickly and cheaply. Bessemer steel built the railroads, bridges and skyscrapers of the next century, and made Bessemer a wealthy man. But he wasn't done inventing.

The steel magnate and mal de mer

In 1868, Sir Henry (we will call him that moving forward, to avoid confusion between the inventor and his ship) took a channel steamer from Calais to Dover. While the English Channel crossing through the Strait of Dover, as this route is called, is and was very common, it wasn't easy. While it took less than a day on the steamship ferries, the shallow channel with its powerful, strange currents was notorious for causing seasickness.

"Few persons have suffered more severely than I have from sea sickness," Sir Henry wrote in his autobiography. The 1868 crossing, followed by a 12-hour train journey, left him temporarily bedridden and, it seems, somewhat traumatized. Determined to rid the world of this scourge, he set his inventive mind to work.

The principle was deceptively simple: A suspended cabin within the ship, which, mounted on gimbals, would remain stable while the outside of the ship was tossed about by the waves. He built a tiny model, "small enough to be placed on a table," and rocked it back and forth using clockwork. It was probably rather adorable.

In December 1869, Sir Henry patented his design and set about building it.

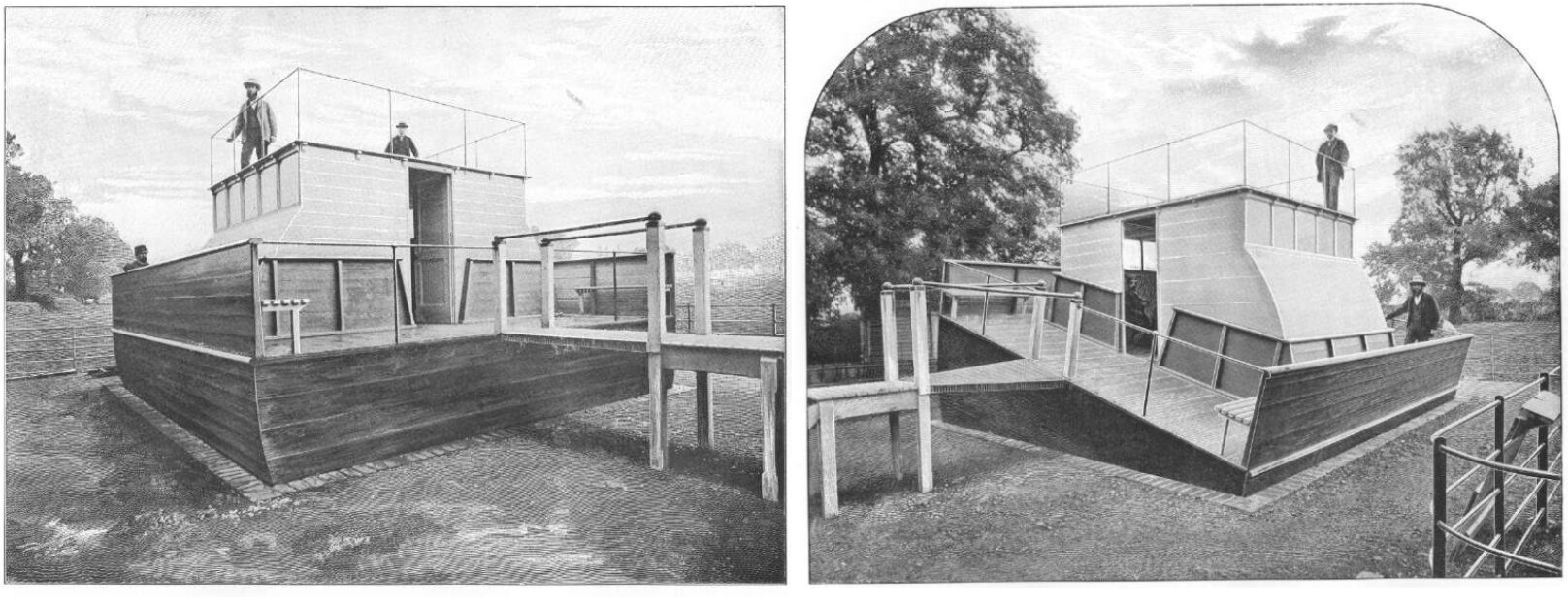

The backyard ship

Rushing into the project, Sir Henry paid a shipbuilder to construct a small steamer for the modern equivalent of over $430,000. No sooner had he done so than he realized he needed to alter his initial design, and the half-built ship wouldn't accommodate the changes. He sold it off for a third of what he'd paid and instead built another model.

Sir Henry was unwilling to actually go out to sea for testing, so he built the middle of a small ship in his backyard. His new design included a steersman. He would manually adjust the level of the cabin by turning a handle to match a spirit level. The motion of the handle would then control the hydraulics.

Sir Henry invited scores of wealthy and prominent friends and fellow inventors to experience the model. They all pronounced it a success, and papers on both sides of the Atlantic reported excitedly that soon seasickness would be a thing of the past.

Building the SS Bessemer

This steersman design satisfied Sir Henry, who formed a joint-stock company and raised $340,000, roughly $34 million today. Joining him in the company was Sir Edward James Reed, who'd been the Chief Constructor for the Royal Navy, and would go on to become a railroad magnate and a member of Parliament.

Designing the ship part of the SS Bessemer was probably somewhat of a low point for him. He'd just bitterly resigned from his Naval command. Parliament had undermined and insulted him by funding the HMS Captain, designed by his detested rival Captain Cowper Phipps Coles, without consulting him. He had something to prove when he decided to join the ambitious new venture.

Sir Henry and Sir Reed sent their plans to Earle's Shipbuilding Company in Hull. Sir Henry continued to bleed money into the project just to keep it afloat.

When the ship was nearly complete and was moored outside Earle's Shipbuilding Company in Hull, a late October gale struck the coast. Too long to be anchored in the regular way, she'd been chained horizontally by both stern and head. As a result, her long side met the full force of the wind, and she was torn from her moorings and driven onto the muddy bank.

She escaped the embarrassing incident without major injury, and they were able to coax her back into the water and finish construction. Finally, after even more personal financial outlay, the ship was insured, and a commander, a Captain Pittock, was found. The maiden voyage of the SS Bessemer was scheduled for May 8, 1875.

A trying trial run

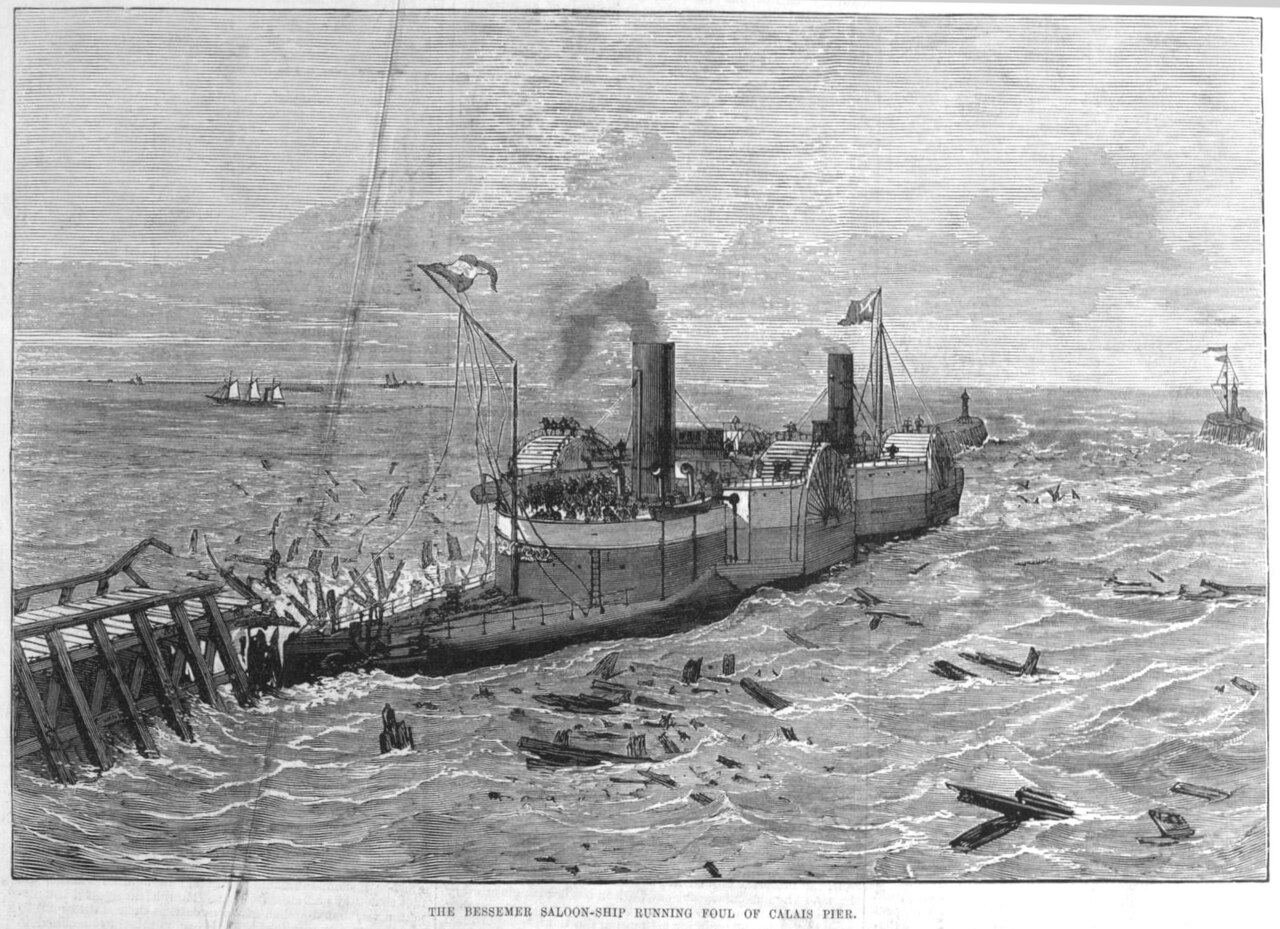

The company wisely decided to perform a trial run before the public debut in May. A few weeks in advance of the date, Captain Pittock took the SS Bessemer out of Dover, planning to dock at Calais and then return.

Unlike many maritime mishaps, weather could not be blamed for what followed. As Sir Henry himself described, the SS Bessemer approached Calais "on a beautiful calm day, in broad daylight, at a carefully chosen time of the tide, and with all the skill of the best Channel navigator."

Whereupon she crashed into the pier. Her paddle wheels slammed into the pier, causing $3,800 in damages and destroying the paddle wheels. Captain Pittock had to go before the consul in Calais, where he swore that the ship simply "did not answer her helm."

She was fitted with replacement paddle wheels, and Pittock managed to carefully inch her back out of the port and limp home to England.

Sir Henry and the company decided it was too late to postpone the May 8 launch. Instead, while the SS Bessemer was being repaired, her creator had the saloon fixed in place, completely defeating the whole purpose of its existence.

Failure continues

Without a doubt, Sir Henry was an incredibly intelligent man with a gift for metallurgy in particular. But he was not a shipwright. The balance of weight in a ship is both important and delicate. The holds of contemporary sailing ships were carefully packed and re-packed to ensure the weight was perfectly distributed. Getting this wrong could negatively affect the sailing abilities of even a very seaworthy vessel.

The SS Bessemer, built around an unwieldy cabin and hydraulics, was already not the easiest sailor. With a great weight constantly shifting the center of gravity, she was practically unsteerable, with dangerously unpredictable movement.

Worst of all, she wasn't even seasickness-proof. Reporting on her maiden voyage, a Wisconsin newspaper wrote that while the design seemed to work in the bay, once she reached the open channel things went awry: "Pitched about by the raging sea, the cabin floundered wildly, and the passengers parted with their victuals as passengers have ever been wont to do."

On her first journey from Hull, where she was built, to Gravesend, she gobbled up coal at an amazing rate. One passenger reported that the saloon itself moved as designed, but either due to mechanical or human error, it didn't respond fast enough to actually negate the movement of the ship.

On the 8th of May, with the first passengers on board and just as ill as always, the SS Bessemer inched into the port of Calais. All breaths were held as Captain Pittock gave his orders-- and the ship failed to respond. The SS Bessemer crashed into the Calais pier for a second time, as Sir Henry put it, "knocking down the huge timbers like so many ninepins!"

The final demise of the SS Bessemer

Sir Henry had sunk a great deal of his personal fortune into developing, building, re-building, and rebuilding a second time. It was an unwillingness to throw good money after bad, not a lack of belief in the concept, that caused Sir Henry to finally pull the plug.

At least, that's what he himself said. That his saloon had proved an entire failure, "nothing could be more absolutely untrue," Sir Henry insisted. It's almost sweet how much he believed in the viability of the wretched little ship despite all evidence to the contrary. At any rate, he never admitted that the concept itself was flawed.

But the second Calais incident killed the SS Bessemer commercially. The bankrupt Bessemer Saloon Steamboat Company was sold off, and the SS Bessemer was sold for scrap. Sir Reed had the saloon itself removed from the ship and installed as a billiards room on his estate in Kent.

Henry Bessemer continued to invent, with varying degrees of success. In 1893, he attempted to build a sun-powered furnace that he promised would reach up to 33,000˚C. However, he gave up after a lens maker failed to produce the required lenses.

In 1889, Sir Reed's estate became Swanley Horticultural College, a women's agricultural school. The beautiful, ornate saloon of the SS Bessemer was used as a lecture hall.

On March 1, 1944, Swanley Horticultural College was bombed in a German air raid. The saloon was destroyed by a direct hit. Only a few pieces of paneling, rescued by local residents, survive.

Humanity has yet to invent a seasick-proof ship, but we do have over-the-counter dimenhydrinate now, which has always worked for me, anyway.

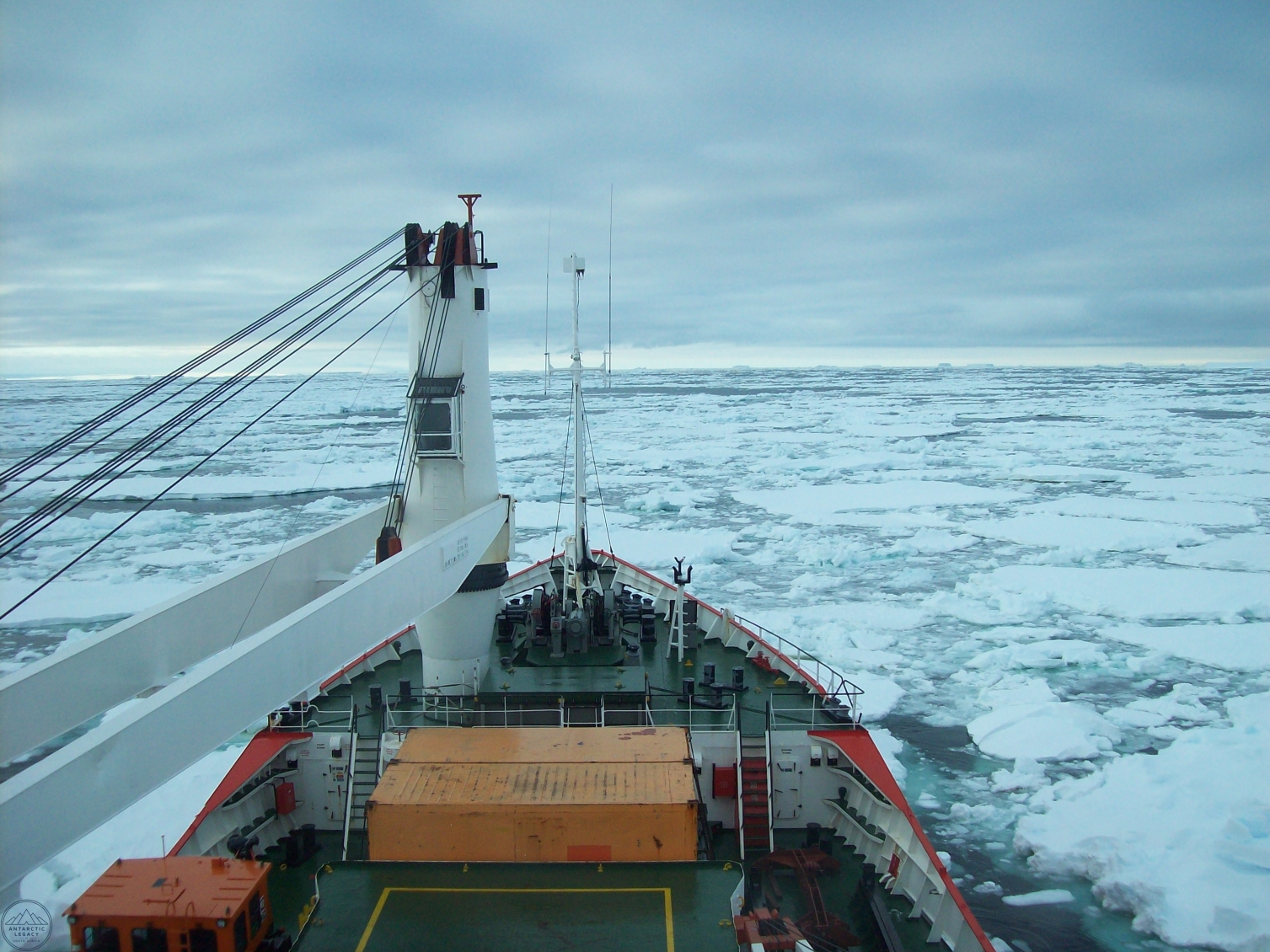

This week's documentary takes us to the frozen Arctic, where a modern expedition follows the route of early 20th-century explorer Hubert Wilkins. In 1931, Wilkins set out for the North Pole in a repurposed military submarine. The subtitle of Frozen North -- "The Disastrous Attempt To Reach The North Pole In A WW1 Submarine" -- hints at how well they fared.

A promising adventurer

Wilkins was raised in Australia. The son of a sheep farmer, he was a self-taught pilot, photographer, and explorer with an abiding interest in the weather. Wilkins first made a name for himself when he flew from Alaska to Spitsbergen, completing the first trans-Arctic airplane flight. He immediately launched himself into the next adventure: reaching the North Pole by submarine.

He chose an old WW1 submarine, which he rented from the U.S. Navy for $1 a year. Interested in his plans, newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst promised Wilkins $250,000 -- worth over $5 million today -- if he could actually reach the North Pole.

Feted in Brooklyn and well-wished by the wealthiest men of the age, the newly christened Nautilus headed North. Wilkins' goals were scientific. He believed, correctly, that polar conditions impacted weather worldwide.

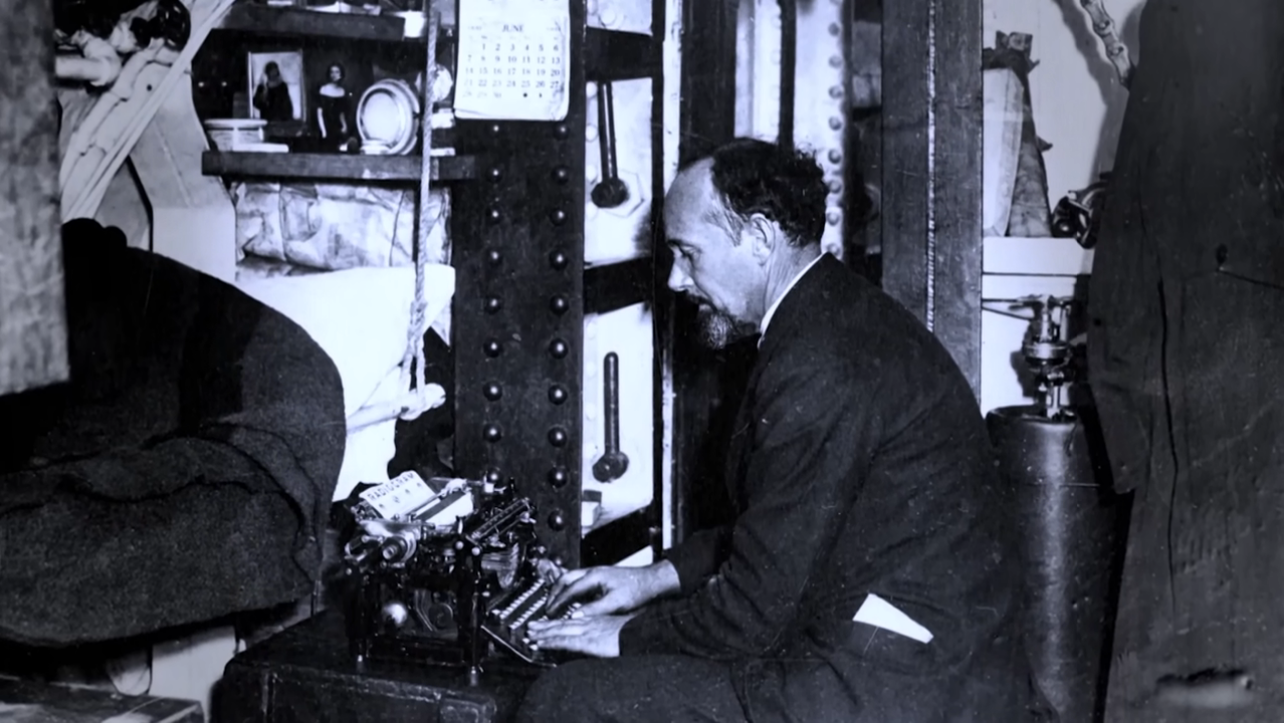

In addition to his meteorological instruments, the ship was fitted with an ice-borer which didn't work, a hydraulic flap to keep it below the ice, and an airlock from the converted torpedo bay. It had no heating or insulation.

The disastrous attempt

Her sea trials went badly, but the season was getting late. It was forge ahead or wait another year, and no polar explorer has ever chosen option two. They left New York with only two months of summer left, with 10,000km to go.

Almost immediately, a storm nearly wrecked them, and the Nautilus sent out an SOS signal. They were rescued and towed the rest of the way to England. Once there, they lost a month to repairs, only halfway to the North Pole. They kept going anyway, making it to Bergen, Norway. Norwegian experts doubted they would survive, and Randolph Hearst sent Wilkins a telegram telling him to call it off. Wilkins ignored this.

It was freezing in the hold, where Wilkins and the researchers conducted observations. They actually did important research, including showing that the Earth is flattened at the poles, instead of a perfect circle. Hopefully, this achievement consoled them through the miserably cold, wet, and cramped conditions.

After doing some science and freezing in the Arctic Ocean, the crew was ready to go home. But that wouldn't satisfy the press, so Wilkins ordered a dive. They were going under the ice.

Under the ice and missing the Pole

Upon inspection, however, Wilkins found the steering mechanism damaged. Historians in cutaway interviews suggest that this was deliberate sabotage by an engineer anxious to go home. Wilkins was unmoved and ordered a dive on the next calm day.

They made it under the ice, becoming the first people to do so. But the radio was damaged, leaving them unable to call for help. At home, newspapers reported them dead.

When they re-emerged, they jury-rigged a radio announcing they were alive. Hearst signaled back that he was glad they were alive and was also cutting off funding. Devastated, Wilkins stayed in the ice for three weeks, taking groundbreaking scientific measurements. It was clear they were not going to reach the Pole.

The Nautilus left the frozen north and limped back to Norway. By the time it arrived, another engine failure had left it unusable. On order of the U.S. Navy, it was scuttled off the coast of Norway.

Diving to the Nautilus

Nearly a century after his failure to reach the Pole, Wilkins' attempt is appreciated as an exploratory and scientific success. But the mystery of the broken steering mechanism lingers.

In a modern two-man submersible, researchers descend to the sunken Nautilus. The modern craft contrasts sharply with the dangerous, dirty, and miserable conditions of the older one, showing how far (with some exceptions) the technology has come.

They found the Nautilus, well preserved in the cold water, but now home to a diverse array of marine life. Researchers focused on the steering gear, looking for signs of deliberate damage. But it's buried in the sediment, preventing them from inspecting it.

Sabotage or not, it was suicidal to dive without those diving rudders, explains oceanographer Raphael Plante. Coming back alive at all was a remarkable achievement.

But Wilkins always dreamed of returning, and proving that submarines were a viable way to explore the North Pole. In March of 1958, a year after Wilkins' death, U.S. Navy submarine USS Skate reached the North Pole. They scattered Wilkins' ashes there.

Later that year, his vessel's namesake, the USS Nautilus, became the first submarine to transit under the North Pole.

In 2023, the world consumed more than 7.3 billion kilograms of tea. Bar water, tea is the most popular beverage on earth. We've even figured out how to drink it in space, where both boiling water and drinking from a cup is a serious endeavor.

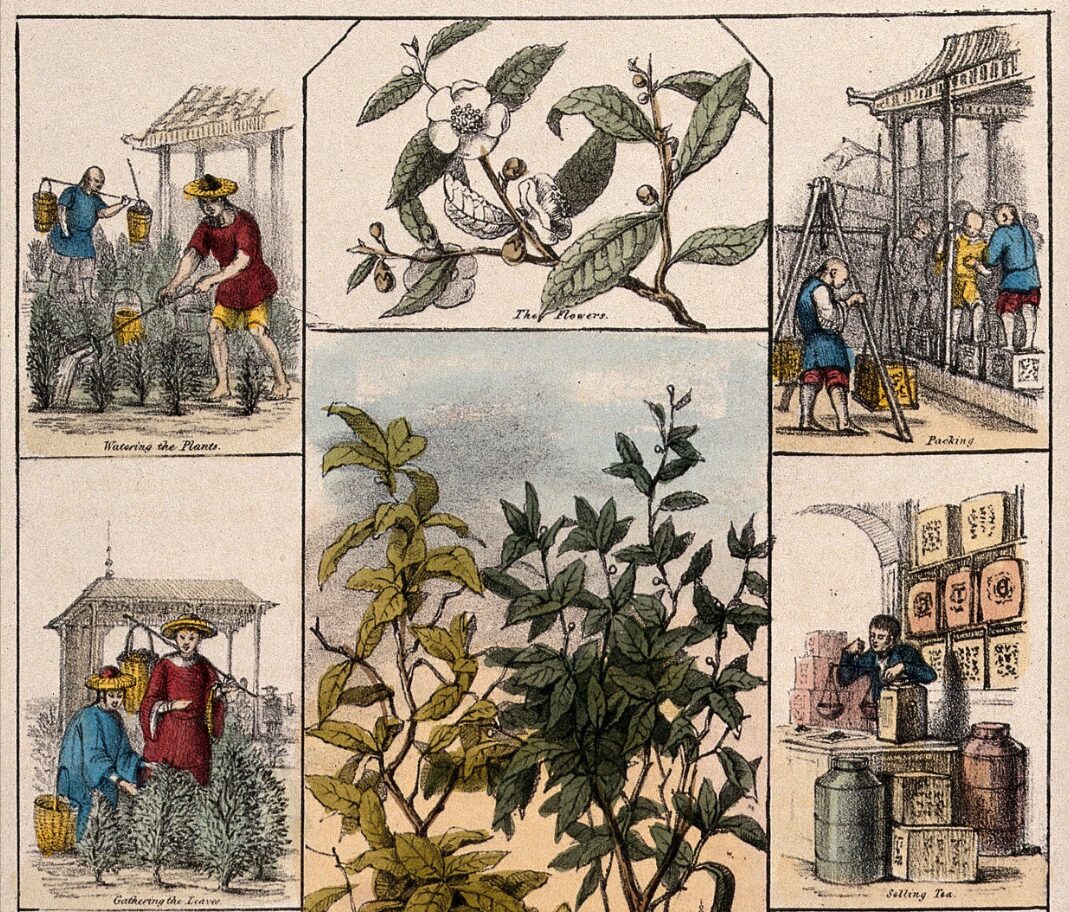

Today, many regions are known for the production and consumption of tea. But for the first few thousand years of its existence, it was synonymous with China.

Tea only reached Europe in the 17th century. When the famous English diarist Samuel Pepys first tried it in 1660, he called it "a cup of tee (a China drink) of which I never had drank before." He did not record whether he liked it or not. Many British people did take to the drink, though, and by 1800, the Brits were importing 24 million pounds from China every year.

British merchants chafed under the trade deficit; their people wanted tea, silk, porcelain, cotton, and indigo. The Chinese didn't seem to want anything but silver. To protect their monopoly, the Chinese government made it illegal to sell live tea plants or their seeds, and closely protected the secrets of tea manufacturing. There was only one way around this: The British were going to have to steal tea from China.

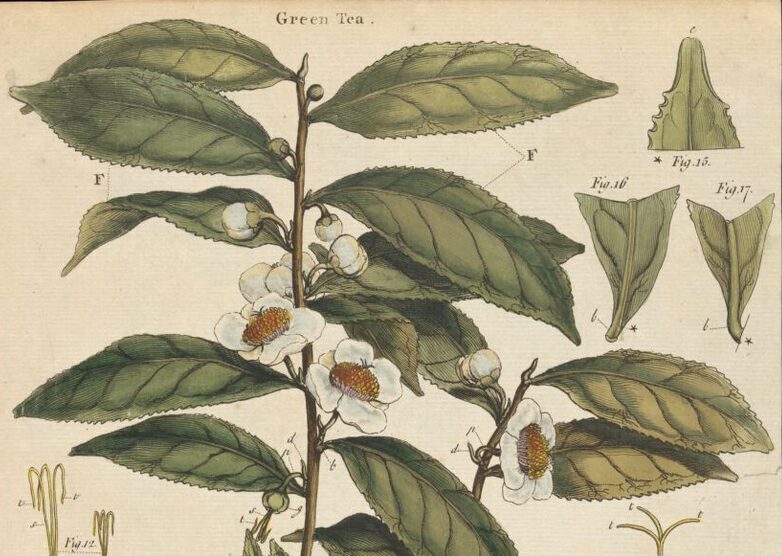

![]()

The most powerful company in history

The British East India Company was one of the most powerful and ruthlessly evil corporations ever to exist, and they had set their sights on taking tea from China.

Formed in 1600, Elizabeth I granted the British East India Company (EIC) a monopoly over all trade east of the Cape of Good Hope. The intention was to create a strong, organized merchant army to break Dutch control of the spice trade.

In 1683, Charles II gave the EIC the unilateral ability to "declare peace and war" with the "heathen nations" of Africa, Asia, and America. The EIC had the right to govern colonies, build plantations and military forts, raise armies, and execute martial law within their territories. The private armies of the EIC conquered much of Southeast Asia, ruling India, Pakistan, Burma, and Bangladesh. They turned these countries into wealth-extraction machines, reducing the inhabitants to desperate poverty.

The company controlled the trade of some of the world's most valuable products: tea, coffee, spices, cotton, silk, porcelain, saltpeter, wool, and slaves. But their monopoly was growing unpopular at home, as it drove up prices and prevented competition. In 1813, the British government opened up trade to India, and in 1833, to China.

But the EIC still had monopolies to trade in a few products, including tea.

A bold proposition

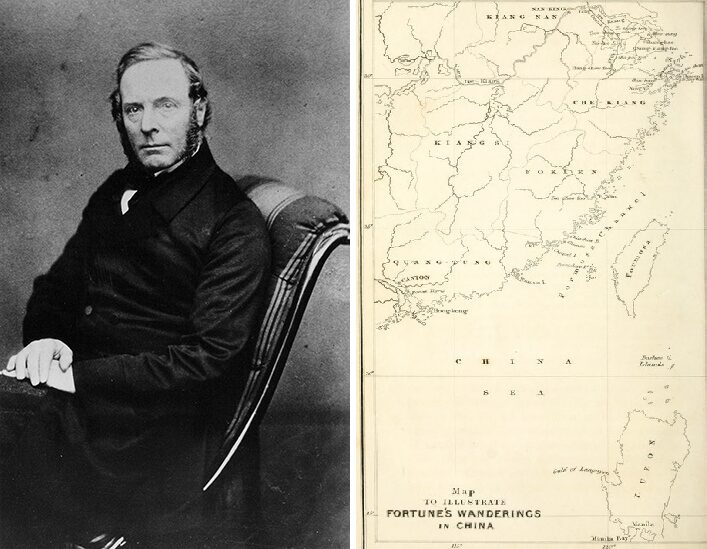

In 1848, Robert Fortune, curator of the Chelsea Physic Garden, was approached by the renowned botanist Dr John Forbes Royle. Royle was an EIC surgeon and the superintendent of the EIC's botanical garden in Saharanpur, India.

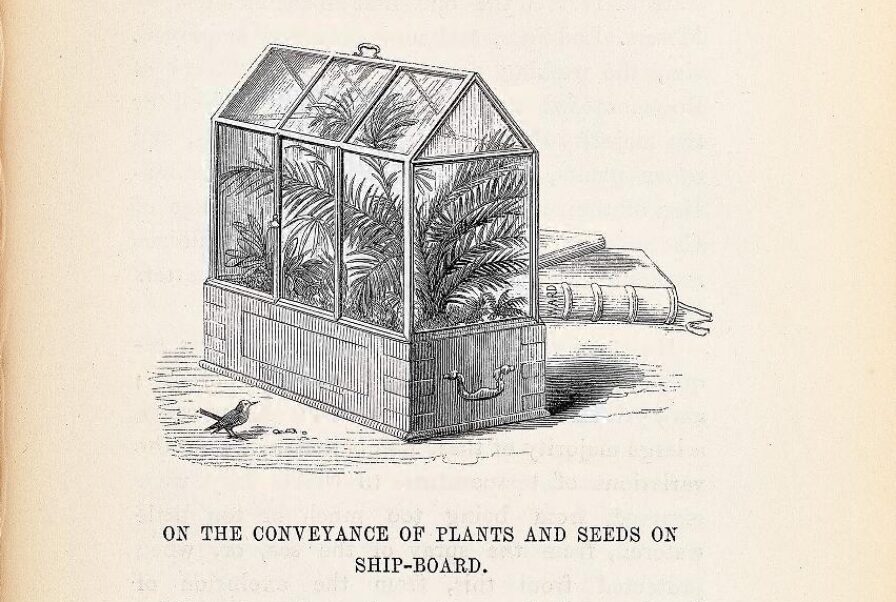

Royle had come to offer him a job, on behalf of his employer. Go to China in disguise, make your way deep into territory never seen by Westerners, and smuggle out living tea plants. Fortune would also need to observe how tea was processed -- a closely guarded secret -- and make it out of the country with his specimens alive. The pay was £500, five times his current annual salary.

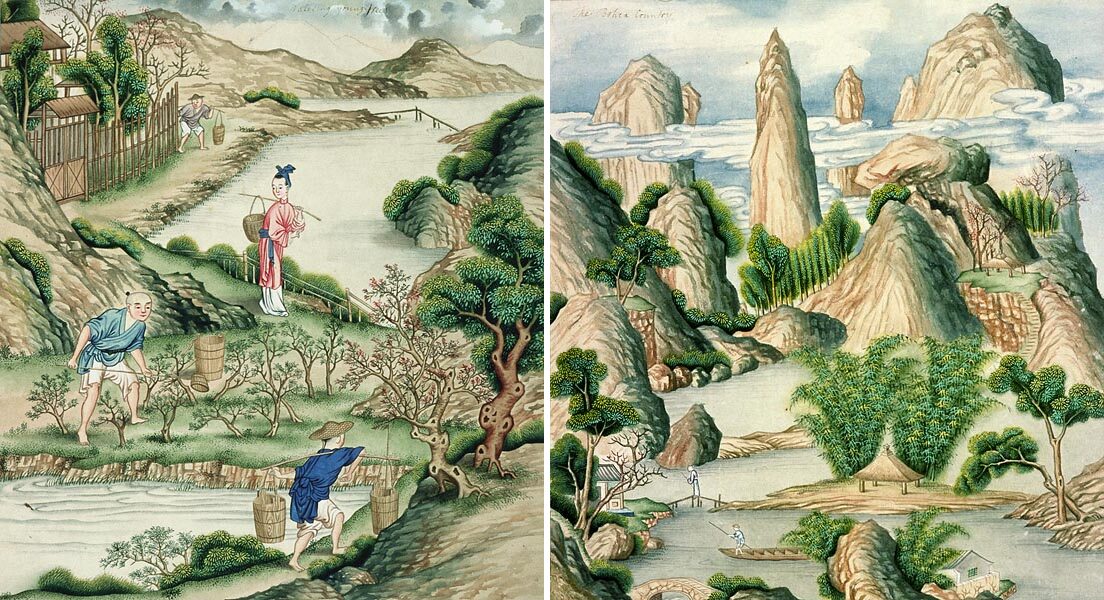

Fortune had already traveled and collected in China, and even observed some parts of the tea growing and collecting process. Before he had gone, many Europeans believed that green tea came from one plant, Thea viridis, and black tea from another, Thea Bohea. Fortune discovered the truth: the difference between green and black tea is in the preparation, not the plant.

Born in Duns, Scotland, in 1812, Fortune came from humble beginnings. He excelled as a gardener on a nearby estate, and in 1839 he moved to Edinburgh to work under William McNab, a celebrated botanist. It was McNab who recommended him to the Royal Horticultural Society in London. The society was sponsoring an expedition to China, allowing Fortune to travel there in 1843.

On that first trip to China, he was attacked by bandits and pirates, battered by typhoons, and nearly killed by fever. He risked death by entering areas banned to foreigners. He also sent back dozens of plants unknown in the West, and brought the art of bonsai to Europe.

In 1848, he agreed to return.

Arrival and disguise

On June 20, 1848, Fortune left Southampton on a passenger steamship. On August 14, it anchored in the Bay of Hong Kong. From there, he traveled up the Shanghai River to the city of the same name, then the northernmost open Chinese port.

It had changed since his last visit. In the harbor, Fortune saw "a forest of masts" from English and American ships, and on shore, a Western port town had replaced the Chinese houses and farms. A steady stream of former Shanghai residents poured from the new settlement into the country, bearing coffins. They were retreating with the remains of their ancestors, to rebury them near their new homes.

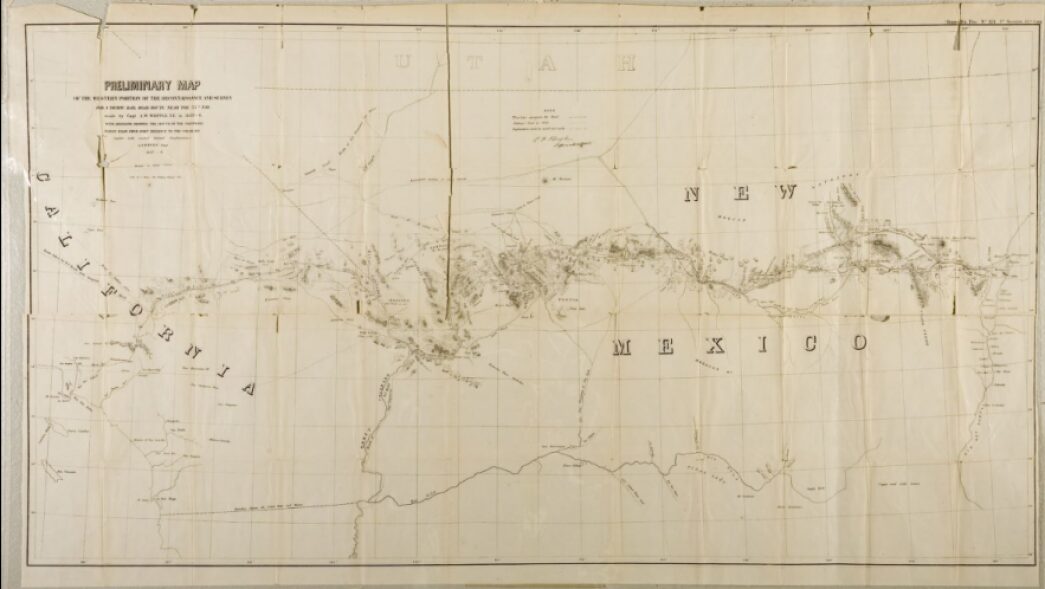

Fortune didn't stay long in Shanghai. His destination was the "great green-tea country of Hwuy-chow." He was referring to famous tea plantations in the Anhui region, deep in the Yellow Mountains. This was where the most celebrated tea was grown, but it was well over 300km from Shanghai, and forbidden to Europeans.

Fortune didn't trust a Chinese agent to get the samples for him. For one, it would take botanical knowledge to keep the samples alive, and two, he believed that "no dependence can be placed upon the veracity of the Chinese." Unlike the Chinese, Fortune was honest and forthright, which was why he decided to disguise himself to infiltrate their plantations and steal from them.

Fortune's hired translator and guide, Wang, rented a boat and found him Chinese clothes. Meanwhile, another servant, a day laborer unnamed by Fortune, shaved his employer's head into a queue hairstyle. Thus attired, they set off in a riverboat headed inland.

Discovering devastation

The boat took them upriver to the city of Hangzhou-Fu. On the way, Fortune passed through several large but "dilapidated" cities. Fortune, like many Western men, considered China a great civilization in ruin, whose ancient glory had fallen to stagnation. But there was another reason for the ruined, half-empty towns.

Stealing the secrets of tea was not the first attempt Britain and the EIC made to adjust the trade imbalance. First, they introduced the Chinese to a desirable product of their own: opium.

Opium wasn't unknown in China, but was used only medicinally. Britain planned to flood the country with the highly addictive drug, forcing Chinese merchants to trade their valuable goods for opium, instead of silver. The EIC could produce opium cheaply in India, and began smuggling it by the ton into China.