Earlier this month, a towering iceberg dangerously close to shore threatened Innaarsuit, a small fishing village in Northwest Greenland. The "skyscraper-sized" iceberg prompted authorities to evacuate some of Innaarsuit's residents to higher ground, according to SkyNews.

Located about 617km north of Nuuk, Greenland’s capital, and 46km north of Upernavik, Innaarsuit is a remote island community of just 169 people, accessible only by boat or helicopter. The village relies heavily on its harbor for fishing, but the iceberg’s proximity endangered homes, the Royal Greenland fish factory, and even the local grocery store. If it calved, or broke apart, the resulting tsunami could have easily swamped the houses on the rocky shore.

You can watch a recent video on it:

This wasn’t the first time Innaarsuit has faced such a crisis. In July 2018, a massive 11-million-ton iceberg, 200m wide and 100m tall, grounded near the village. Again, residents near the shore were evacuated, and the village’s power plant and fuel tanks were at risk. Fortunately, the iceberg drifted north after a few days, averting disaster.

Other incidents

Greenland has experienced several tsunami incidents in recent years. On June 17, 2017, a massive landslide in Karrat Fiord triggered a wave that struck Nuugaatsiaq (about 92km north-northwest of Innaarsuit), killing four people and injuring 11, washing several houses into the sea, and flinging boats 50m up the hillside. The landslide, likely caused by melting permafrost due to rising temperatures, highlighted the growing risks to coastal communities.

Another dramatic incident occurred in June 2018 near Ilulissat, known as Greenland’s Iceberg Capital, thanks to its UNESCO-listed Icefiord. A 6.4km-long iceberg calved and sent huge waves crashing toward the shore, again forcing residents to flee to higher ground.

A time-lapse video of the 2018 Innaarsuit iceberg:

Icebergs near Greenland’s shores often ground in shallow bays, where they can suddenly calve or flip. Warm weather accelerates melting, increasing calving risks, while ocean currents and winds can either push icebergs away or trap them closer to shore.

This month's iceberg in Innaarsuit raised similar concerns. However, in the end, it dislodged from the shallows and drifted away, sparing the shoreline structures.

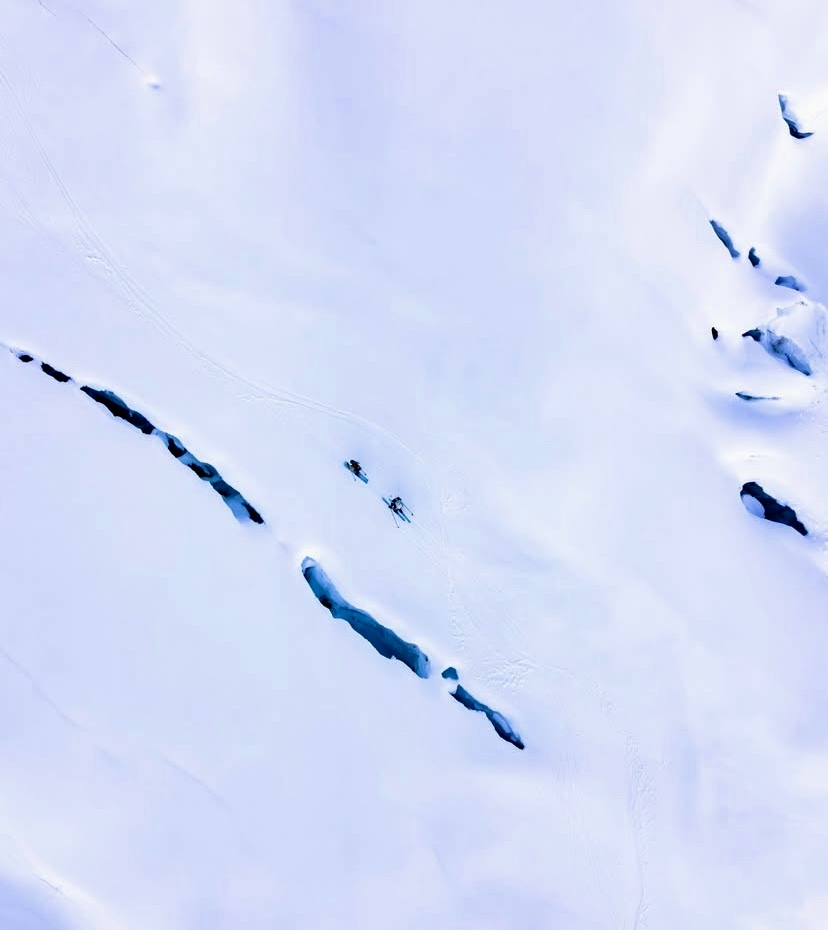

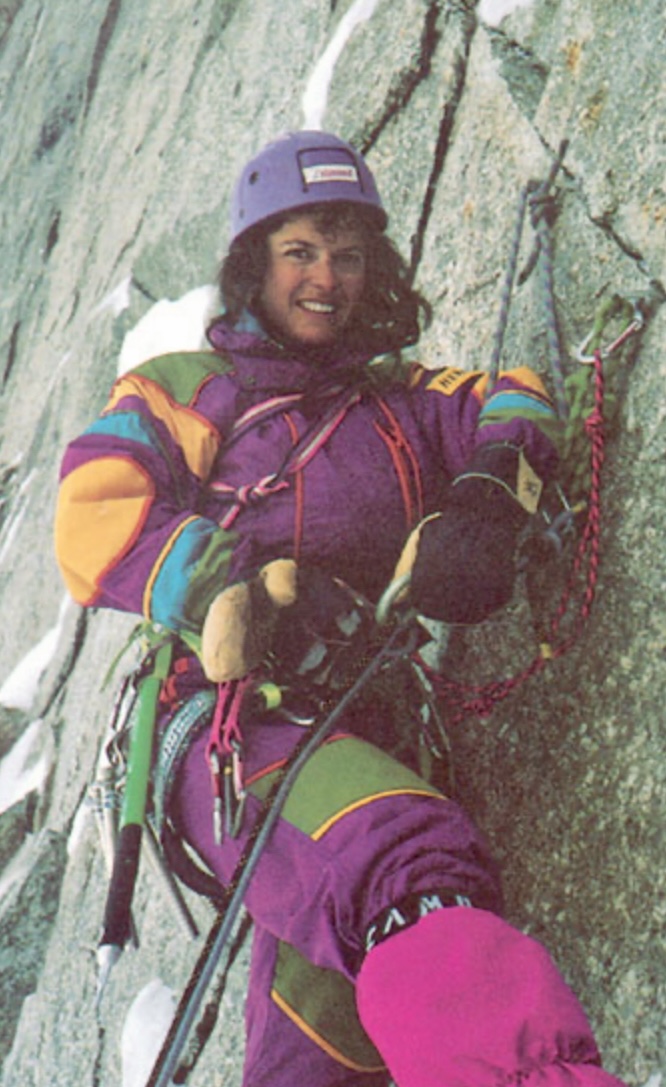

Shira M. Biner, Kelly Fields, and Heather B. Smallpage have done a new 550m big-wall route on Eglinton Tower’s buttress on Baffin Island, Canada. This marks the first route of its length and difficulty (5.11+ A0) by an all-female team on Baffin Island. The group included Natalie Afonina.

The daunting buttress rose approximately 893m above their Base Camp, with a challenging headwall that appeared nearly unclimbable from below. Over 12 long pitches and one cold bivouac, they summited of the first tower, only to discover a hidden 300m headwall leading to the true summit. Prioritizing safety and limited by food and energy, the team celebrated their milestone and made an 11-hour descent. The route included a tension traverse to avoid dangerous runout moves, but the climbers noted it could go free with one or two bolts.

Kelly Fields shared a personal reflection on her social media: “The summit was never my goal — surviving the ominous headwall was. I climbed with a respiratory infection and debilitating blisters, driven by a lifelong dream. Nothing and no one was going to stop me.”

She highlighted the team’s grit, climbing together for the first time and tackling an “insanely difficult and dangerous objective” in good style.

A long approach

The expedition included 250km of skiing on sea ice, paddling the Kogalu River, and trekking through Ayr Pass.

Eglinton Tower (933m) lies in remote Auyuittuq National Park's Weasel Valley, near other prominent Arctic peaks like Mount Thor and Mount Asgard. According to the American Alpine Journal, its first recorded ascent was in 1934, by British climbers John Hanham and Tom Longstaff. That ascent was part of early exploratory mountaineering in Baffin Island, focusing on peak bagging rather than technical big-wall routes. The climb marked the tower as one of the earliest summited peaks in the region. However, it’s not a frequently climbed peak, due to its remoteness.

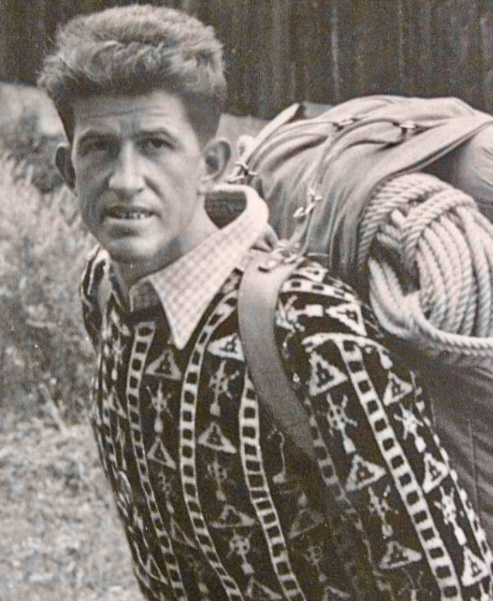

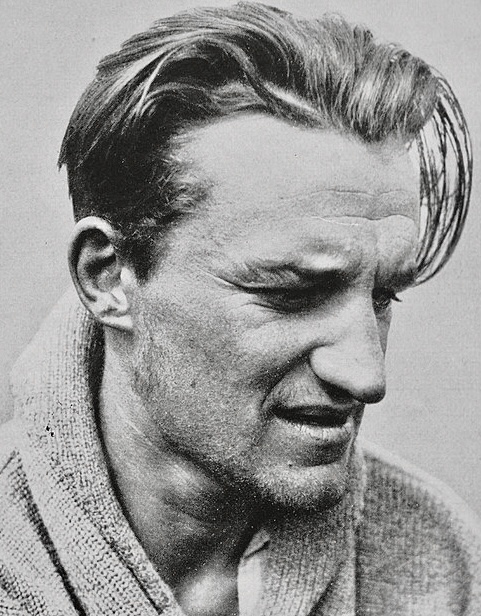

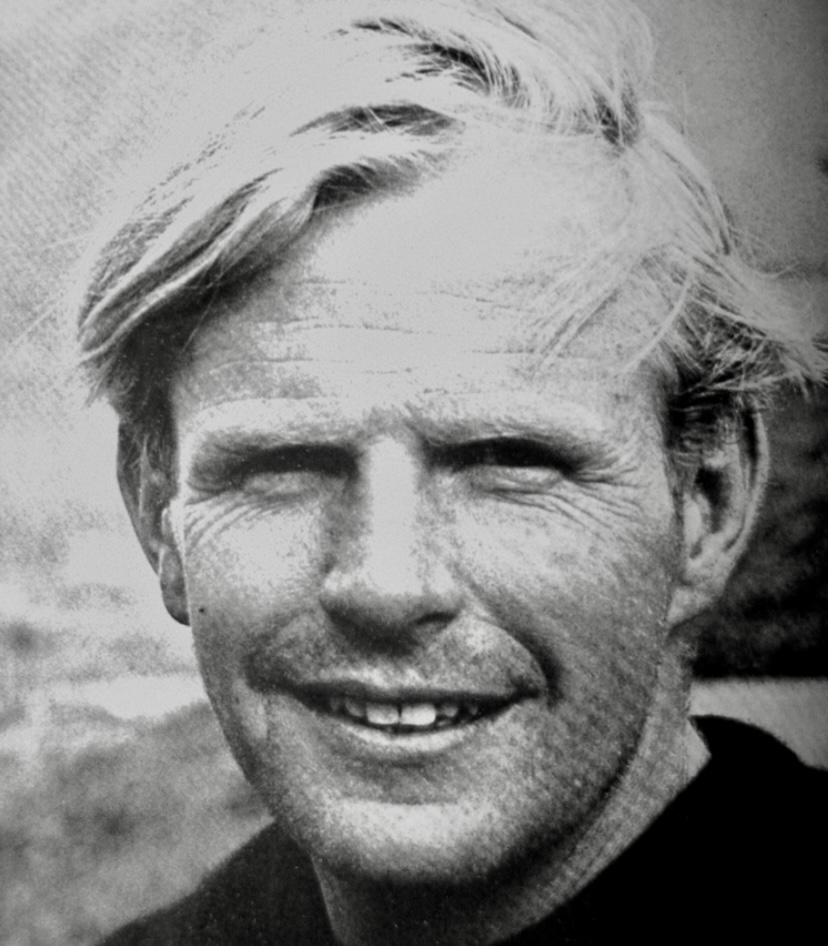

Today, July 25, would be the 104th birthday of Lionel Terray. The celebrated French alpinist climbed routes from the Alps to the Himalaya to the Andes, and also wrote one of the all-time great mountaineering books, Conquistadors of the Useless.

Early years

Lionel Terray was born on July 25, 1921. Growing up in Grenoble near the French Alps, Terray discovered mountaineering and skiing as a child. A conversation with his mother, who dismissed climbing as a stupid sport involving scaling rocks with your hands and feet, sparked his curiosity.

By age 12, Terray was climbing peaks like the Aiguille du Belvedere and the Aiguille d’Argentiere with his cousin. By 13, the talented youngster was leading climbs. But Terray’s love for the mountains caused problems; he got kicked out of one boarding school and ran away from another to pursue ski racing. With little family support, he got by on his own. Skiing was Terray’s first love, and as a teen, he won prizes in competitions, which gave him some money.

In 1941, during World War II, Terray joined Jeunesse et Montagne, a military program that kept him in the mountains. There, he met lifelong friends and climbing partners Gaston Rebuffat and Louis Lachenal.

In 1942, Terray carried out the first ascent of the west side of Aiguille Purtscheller. He also climbed the difficult Col du Caiman. From 1943 to 1944, Terray served in a high-mountain military unit. In 1944, he joined the French resistance, using his mountain skills against the Nazis.

Terray knocked off other notable first ascents, such as the east-northeast spur of the Pain de Sucre and the north face of Aiguille des Pelerins with Maurice Herzog in 1944.

A rising star

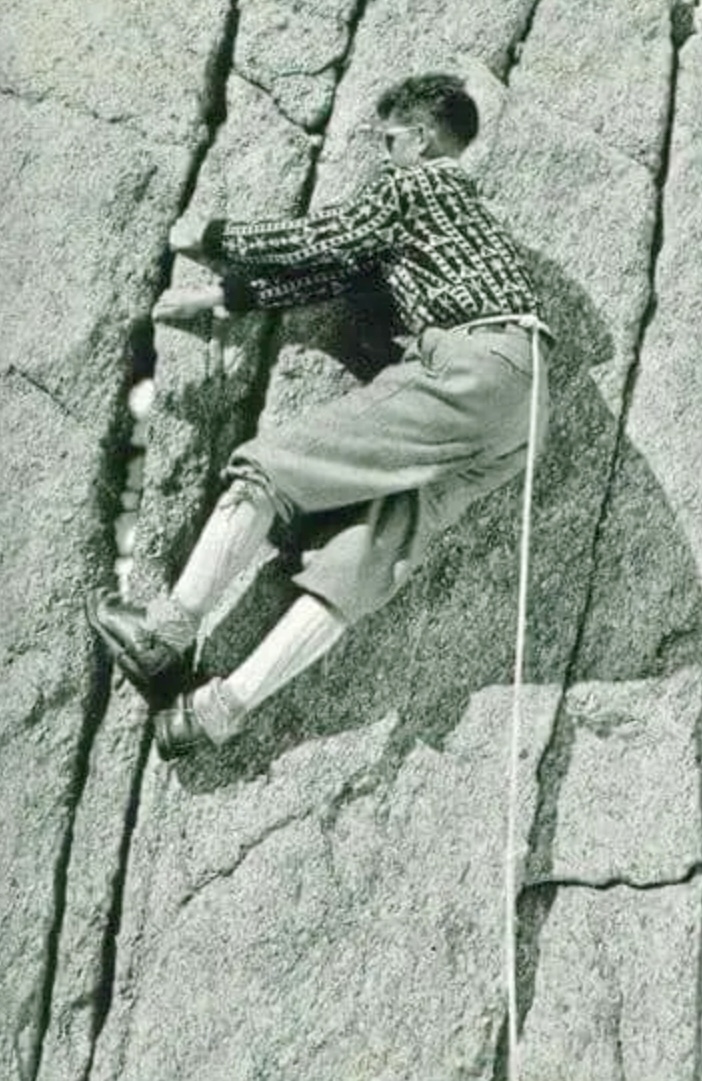

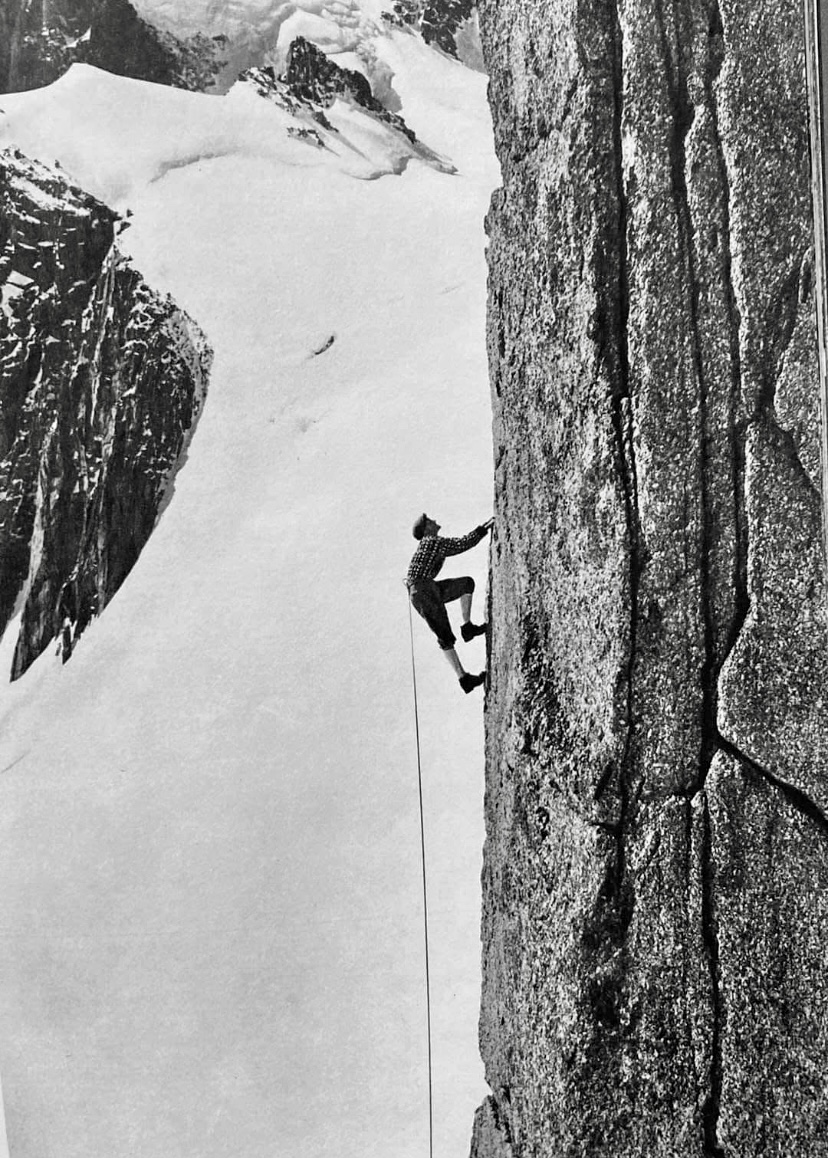

After the war, Terray became a mountaineering instructor and settled in Chamonix as a freelance guide. With Lachenal, he did some of the Alps’ most difficult routes, including the Droites’ north spur in only eight hours in 1946, the Walker Spur of the Grandes Jorasses in 1946, the northeast face of Piz Badile, and the north face of the Eiger in 1947 (the second-ever ascent). Terray's speed and skill earned him a reputation as a climbing prodigy.

A rescue attempt on Mont Blanc

In late December 1956, Lionel Terray took part in a rescue attempt on Mont Blanc’s Grand Plateau. At about 4,000m, young climbers Jean Vincendon and Francois Henry were stranded after a failed attempt on the Gouter Route, a popular 1,800m climb to Mont Blanc’s summit.

On December 22, a blizzard caught Vincendon and Henry near the Vallot Hut at 4,362m. Freezing and frostbitten, they couldn’t descend. Terray, now a Chamonix guide, defied the Compagnie des Guides’ decision to postpone a rescue because of the extreme risks of strong winds and freezing temperatures.

Terray’s team battled brutal weather for two days but couldn’t reach the climbers. A military helicopter, attempting a parallel rescue, crashed near the Vallot Hut, stranding its crew. Terray’s group retreated, exhausted, as conditions worsened.

French Army instructors finally reached Vincendon and Henry in early January, but found them near death from exposure and frostbite. Evacuation was impossible, and both climbers died.

Terray’s rescue effort led to his expulsion from the guides’ organization, sparking controversy in Chamonix.

Eiger rescue

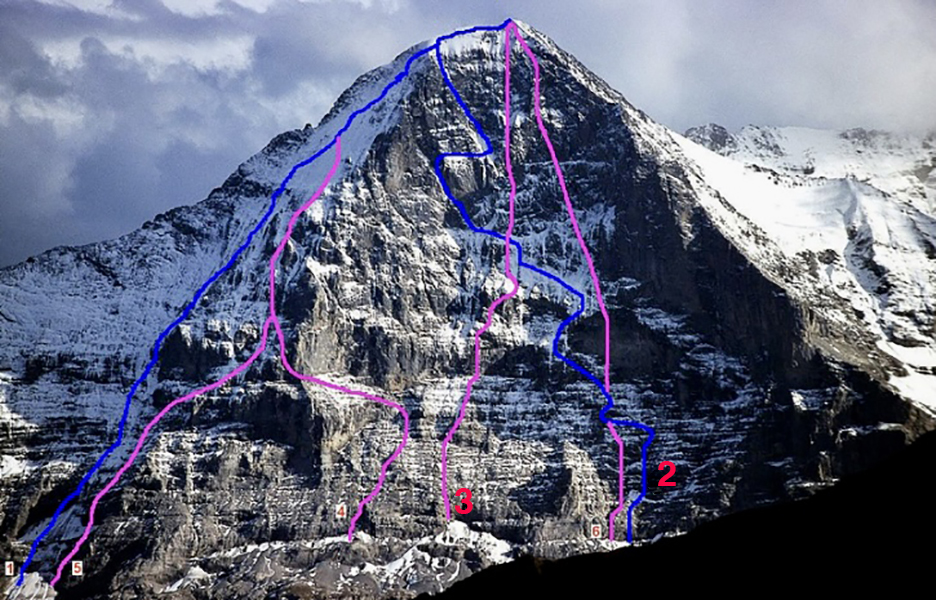

In the summer of 1957, Terray took part in a complicated rescue on the Eiger’s North Face in the Swiss Alps. Two Italian climbers, Claudio Corti and Stefano Longhi, were stranded after an avalanche hit their team during an attempt on the notorious Nordwand. The route, known for its steep ice, rockfall, and brutal weather, had already killed their partners, and Corti was injured.

Terray, then 35, joined a multinational rescue team at Kleine Scheidegg. The climbers were stuck near the Difficult Crack, at around 3,300m. Terray, with German climbers Wolfgang Stefan and Hans Ratay, ascended via ropes and pitons. They battled harsh winds and -20°C temperatures. After two days, they reached Corti, who was hypothermic but alive, clinging to a ledge. Longhi, lower down, was too weak to move. Terray secured Corti with ropes, and the team lowered him 600m to safety. Longhi, barely conscious, died during the descent when his rope jammed.

The effort, involving 50 people, was one of mountaineering’s greatest rescues.

Other historic climbs

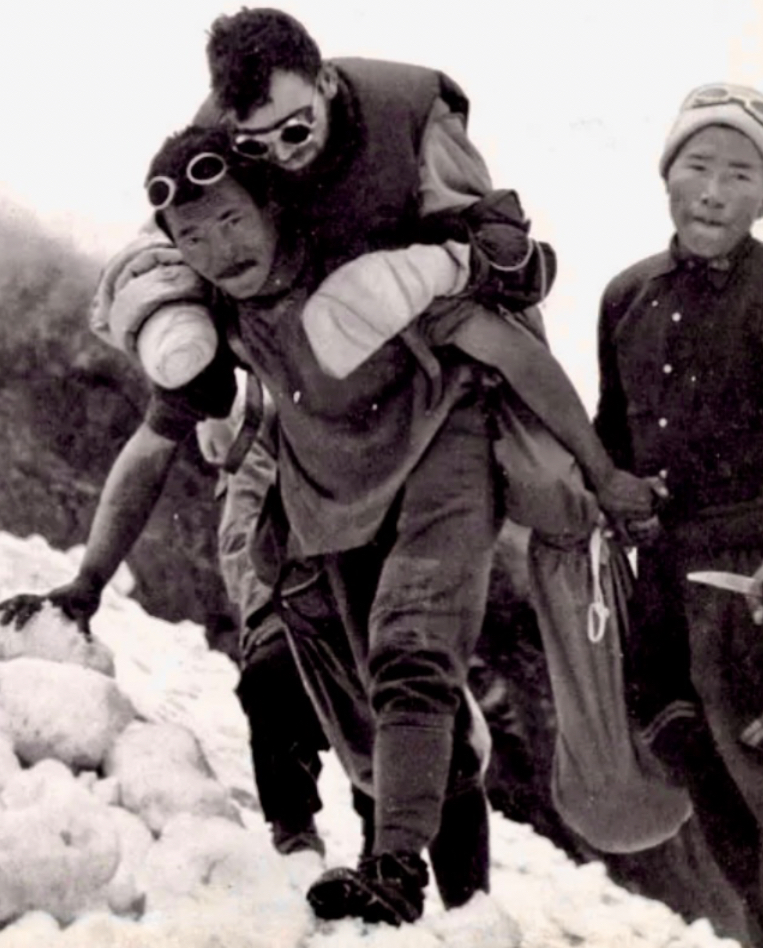

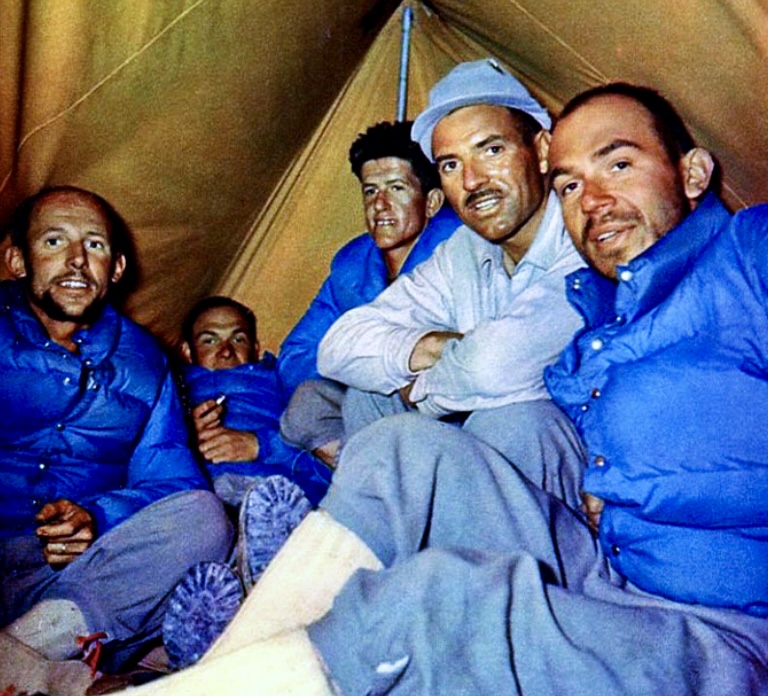

Terray’s ambition took him beyond the Alps. In 1950, he joined Maurice Herzog’s expedition to 8,091m Annapurna I in the Himalaya, the first confirmed ascent of an 8,000m peak. Terray and Rebuffat's efforts, alongside one of the Sherpas, were crucial to helping the frostbitten Herzog and Lachenal descend safely. The climb brought global fame for the French team.

In 1952, Terray and Guido Magnone made the first ascent of Cerro Fitz Roy in Patagonia. That year, Terray also climbed 6,369m Huantsan in Peru with Cees Egeler and Tom De Booy.

In 1954, Terray summited 7,804m Chomo Lonzo with Jean Couzy, paving the way for their legendary 1955 first ascent of 8,485m Makalu. In 1962, Terray led the first ascent of 7,710m Jannu in Nepal, and in the summer of 1964, he led the first ascent of 3,731m Mount Huntington in Alaska.

In Peru, Terray made first ascents of peaks like 6,108m Chacraraju, considered the hardest peak in the Andes at the time, along with 5,350m Willka Wiqi, 5,428m Soray, and 5,830m Tawllirahu.

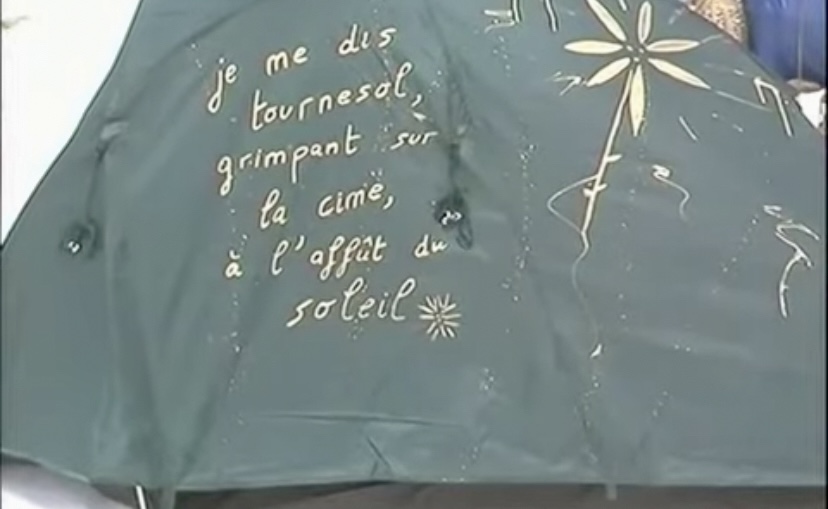

Conquistadors of the Useless

In 1961, Terray published Les Conquerants de l’inutile (Conquistadors of the Useless), a memoir that blends vivid accounts of his climbs with reflections on the purpose of mountaineering. The title captures his view that climbing, though seen as pointless by some, was a noble pursuit. The book, translated into several languages, remains a classic.

A tragic end

On September 19, 1965, Terray and his friend Marc Martinetti died in a climbing accident in the Vercors massif near Grenoble. Terray was just 44.

The pair was descending the Gerbier, a limestone cliff in the Vercors range, after completing a route. They were roped together when their rope -- likely weakened or damaged -- snapped. They fell more than 200m to the base of the cliff. Both climbers died on impact. Chamonix mourned deeply, and his funeral drew figures like Herzog, Rebuffat, and Leo LeBon.

"He was to many a great and dear friend, and all those who paid him tribute before he was laid to rest in the Chamonix Cemetery, among them hardened mountain climbers, wept like small children. To the French climbing world, especially the younger generation, his absence represents an irreplaceable loss, as he was the hero of their dreams, and could hold an audience breathless as no one ever has been able to," Lebon wrote in the American Alpine Journal.

Terray’s legacy lives on through his climbs, rescues, and writings. His son, Nicolas, is a mountain guide. Known for his red beanie and sunglasses, Terray appeared in films like Etoile du Midi, La Grande Descente, and Stars Above Mont Blanc.

You can watch Etoile du Midi below, with the option of automatic subtitles:

On July 19, two French climbers, a 25-year-old woman and a 56-year-old man, lost their lives on Mont Blanc in the Alps. The Peloton de Gendarmerie de Haute Montagne (PGHM) of Chamonix recovered their bodies from the base of 4,052m Aiguille de Bionnassay.

According to Aostasera, the climbers likely fell from the ridge of the Aiguille de Bionnassay, a technical route to Mont Blanc requiring significant experience. The search began Friday evening after family members, concerned by their failure to return, alerted authorities. The PGHM located the bodies on Saturday. Authorities have opened an investigation to determine the exact cause of the accident.

A deadly couple of years

This incident follows other recent fatalities in the Mont Blanc massif. On June 10, two climbers, a man and a woman in their 40s, were found dead below the Aiguille du Tricot on the Bionnassay Glacier, also likely from a fall.

On September 10 last year, two Italians and two South Koreans died of exhaustion after harsh weather stranded them near the summit of Mont Blanc. The next day, a 61-year-old Danish hiker fell 30m to his death near Saint-Gervais-les-Bains. On August 22, 2024, two Spanish climbers died in a rappelling accident on Mont Blanc du Tacul’s Gervasutti Couloir, and a 67-year-old climber fell into a crevasse on the Dome du Gouter.

Additionally, on July 13, 2025, a fatal accident occurred on the nearby 4,357m Dent Blanche in Switzerland’s Canton Valais, close to the Italian border. Two Austrian climbers, part of a group of five, fell on the mountain’s west face. A 46-year-old woman died, while her 46-year-old companion remains missing despite extensive search efforts complicated by adverse weather and rugged terrain, according to the Valais Cantonal Police.

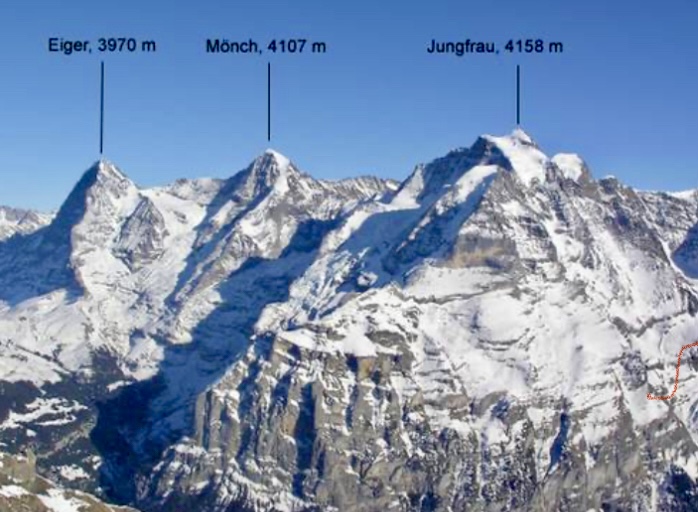

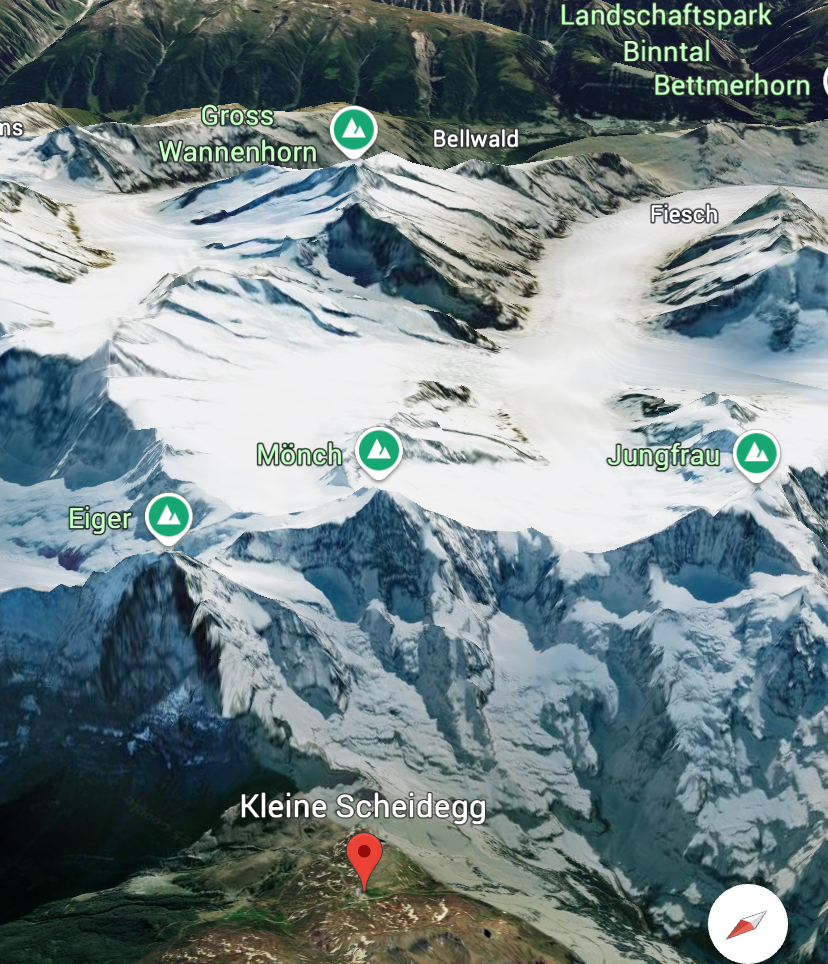

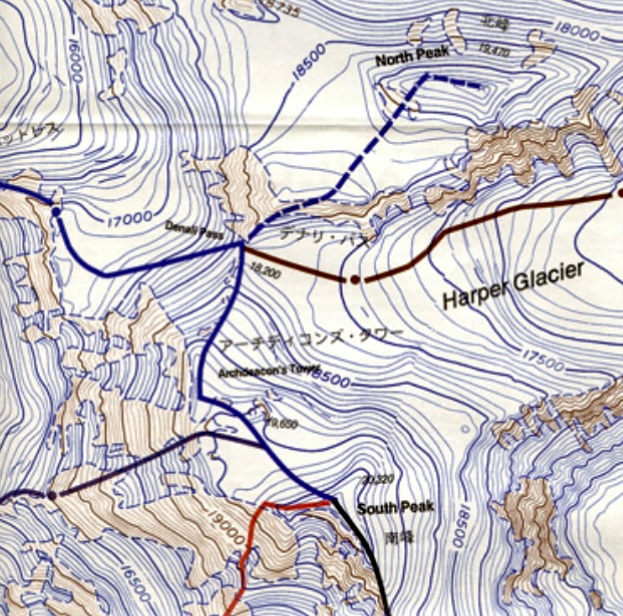

A mountaineering dispute continues to simmer after climber Stephan Siegrist questioned a new speed record set by Nicolas Hojac and Philipp Brugger. Brugger and Hojac had climbed the north faces of the Eiger, Mönch, and Jungfrau in Switzerland’s Bernese Oberland in April 2025.

The controversy then expanded, with some questioning Siegrist's 2004 record with Ueli Steck. The argument raises issues about transparency, ethics, and route choices. The dispute was explained earlier this month by Swiss climbing magazine Lacrux and German mountaineering magazine Bergsteigen.

The issue

In April 2025, Swiss climber Nicolas Hojac and Austrian Philipp Brugger set a speed record by climbing the north faces of Eiger, Mönch, and Jungfrau in 15 hours and 30 minutes. They surpassed the 2004 record set by Swiss climbers Ueli Steck and Stephan Siegrist by 9 hours and 30 minutes.

Hojac and Brugger praised Steck and Siegrist for their pioneering effort, but Siegrist argued their record wasn’t comparable. He alleged that Hojac and Brugger paused timing during breaks and chose a different route on the Jungfrau: the Lauper Route. According to Siegrist, the Lauper Route is not a "true" north face route, unlike the Ypsilon Couloir Route he took in 2004. He contacted their shared sponsor, who filmed the project, demanding an honest report and a correction to the press release.

Hojac and Brugger, stunned by the accusations, countered with transparency, providing GPS tracks, videos, and photos to prove they followed the classic routes Steck and Siegrist reported in 2004, including the Lauper Route on the Jungfrau. They had consulted Siegrist before their climb, relying on his documented route descriptions.

Controversy shifts

The controversy shifted dramatically when Hojac and Brugger discovered that Siegrist had retroactively changed details about his 2004 climb on his website this spring. Siegrist now claimed that he and Steck climbed Jungfrau’s Ypsilon Couloir (rated EX -- extremely difficult) instead of the Lauper Route. Previously, Siegrist had stated that they climbed the Lauper Route in his book, on his website, and in a pre-climb phone call with Hojac. The book, published years earlier, still lists the Lauper Route and cannot be altered, exposing Siegrist’s inconsistency.

Siegrist also recently admitted that he and Steck were aided by a 50m rope, lowered by two other climbers, to exit the Jungfrau. This detail remained hidden for 21 years.

This external assistance, deemed unethical in speed climbing, could disqualify their record because unaided ascents are standard for such feats. Hojac labeled this hidden information a "fraud."

Hojac argued Siegrist’s criticisms stemmed from jealousy. The sponsor urged a private resolution, but the public dispute revealed Siegrist’s alterations and reinforced Hojac and Brugger’s credibility.

The three North Face routes

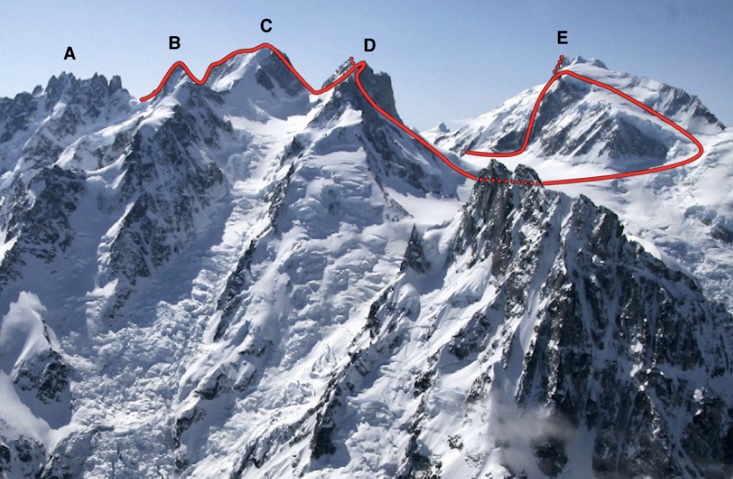

The Bernese North Face Trilogy involves climbing the north faces of three iconic peaks: 3,967m Eiger, 4,107m Mönch, and 4,158m Jungfrau. Each presents unique challenges.

The Heckmair Route on Eiger’s North Face is a 1,800m climb on mixed terrain. It was first ascended from July 21-24, 1938, by Anderl Heckmair, Ludwig Vörg, Heinrich Harrer, and Fritz Kasparek. It is graded ED2 (extremely difficult two) in the alpine grading system, UIAA V-, and features ice climbing sections up to 70°. This route has challenging sections like the Hinterstoisser Traverse, Ice Hose, and Death Bivouac. Both duos, Siegrist-Steck and Hojac-Brugger, used this route.

The Lauper Route on Mönch’s North Face involves steep snow and ice. Both teams followed this route, which was first ascended on July 23, 1921, by Hans Lauper and Max Liniger. This line, also known as the North Face Rib or Nordwandrippe, is a challenging mixed climb graded TD (very difficult) that follows a prominent rib dividing Mönch’s North Face.

The recent dispute centers on the Jungfrau. Hojac and Brugger climbed the Lauper Route, documented by Steck and Siegrist in 2004. The Lauper Route was first ascended in 1934 by Hans Lauper and Alfred Zurcher. Although less difficult than the Eiger’s Heckmair Route, it involves steep terrain and a challenging exit. It’s graded around D (difficult) or higher, depending on conditions.

This spring, Siegrist claimed that he and Steck had taken the Ypsilon Couloir and not the Lauper Route. The Ypsilon Couloir was first ascended in 2001 by Siegrist and Ralph Weber, and its exit is rated EX (extremely difficult).

The Eiger, Mönch, and Jungfrau remain alpine benchmarks, but this controversy underscores the need for clear speed-climbing rules to ensure fair records. The trilogy dispute mirrors broader mountaineering debates, such as unscrutinized 8,000m peak records involving time, Sherpa support, or supplemental oxygen.

You can watch a documentary about Hojac and Brugger's climb called The Fast Line here. Subtitles in different languages are available.

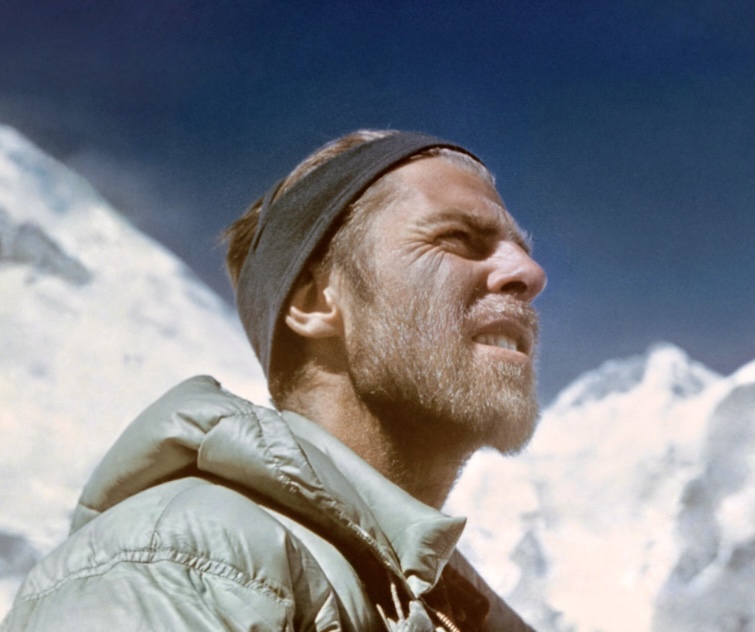

Kim Chang-ho was a South Korean mountaineer who summited the 14x8,000'ers without supplemental oxygen in record time. He pioneered numerous new routes and first ascents on 6,000m and 7,000m peaks. Today, we revisit his most notable climbs.

Early years

Most sources list Kim's birthday as September 15, 1969, but mountaineering historian Bob A. Schelfhout Aubertijn confirmed that Kim was born on July 13, with confusion arising from the Korean age system.

In 1988, Kim began studying International Trade at the University of Seoul. Inspired by Alexander the Great's exploits, Kim started climbing with the university’s Alpine Club.

His frequent expeditions delayed his academic progress, and he didn’t earn his Business Administration degree until 2013. Kim viewed his humanities studies as a way to enrich his climbing. He believed that understanding culture and history deepened his connection to the mountains.

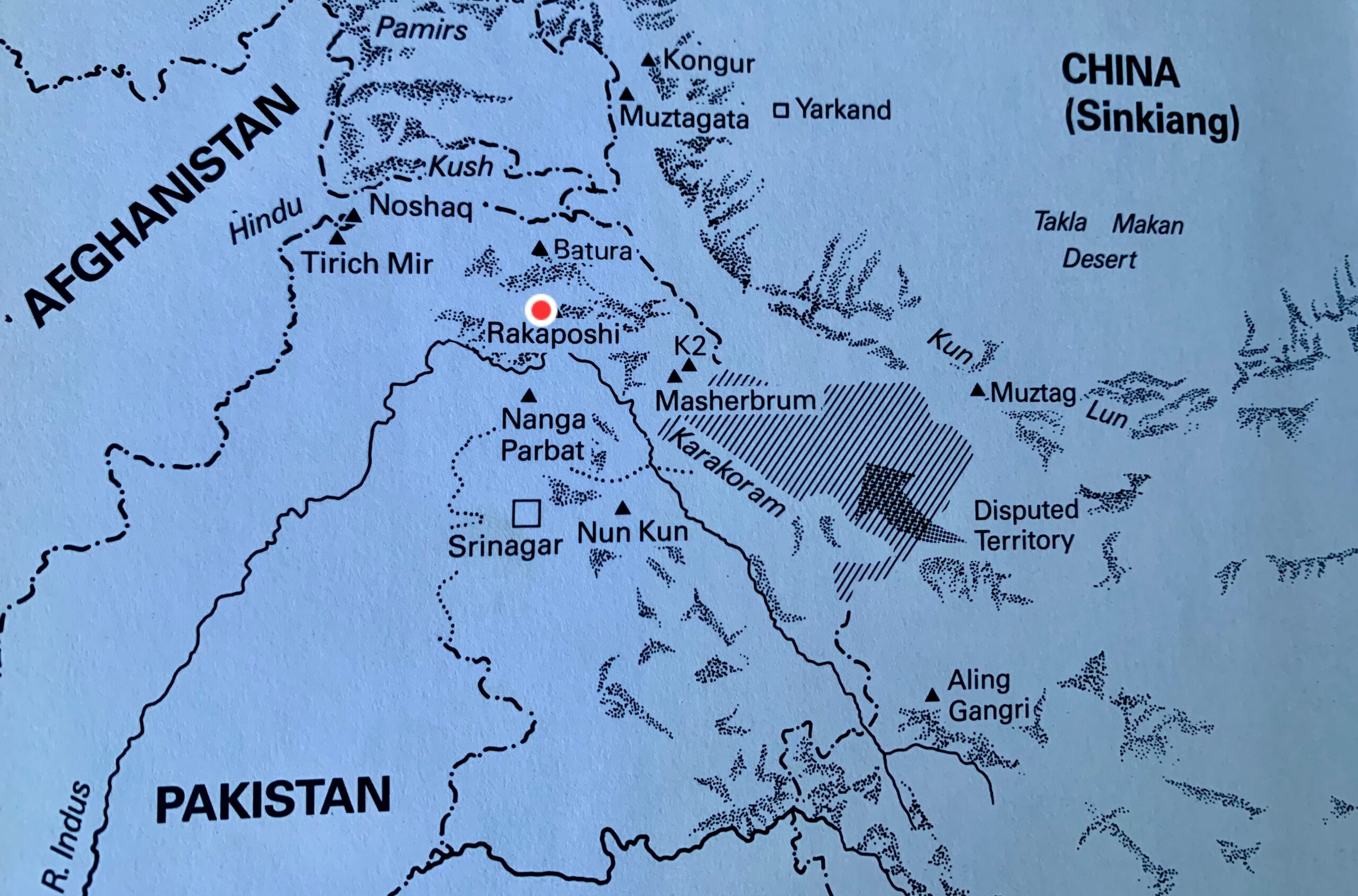

By the 1990s, he was already tackling rock-climbing routes up to 5.12. Early expeditions to the Karakoram, including attempts on 6,286m Great Trango in 1993, and 7,925m Gasherbrum IV in 1996, revealed his bold -- sometimes reckless -- ambition. On Gasherbrum IV, he reached 7,450m but faced a sheer rock face without protection, instructing his partner to release the rope if he fell.

Exploration of northern Pakistan

Between 2000 and 2004, Kim embarked on solo trips in northern Pakistan’s Karakoram, Hindu Kush, and Pamir ranges, prioritizing discovery over summits. As detailed in the 2023 American Alpine Journal, he surveyed glacial valleys, documented hundreds of unclimbed peaks, and built relationships with local farmers and herders. These solitary treks were driven by a desire to understand the geography, culture, and history of the regions.

Kim’s journals reveal a meticulous approach, with photographs and descriptions of potential routes forming a database that remains a valuable resource for climbers. His interactions with locals shaped his climbing decisions, ensuring cultural sensitivity in his choice of peaks. This period of exploration laid the groundwork for his later ascents, blending adventure with respect for the human and natural contexts of the mountains.

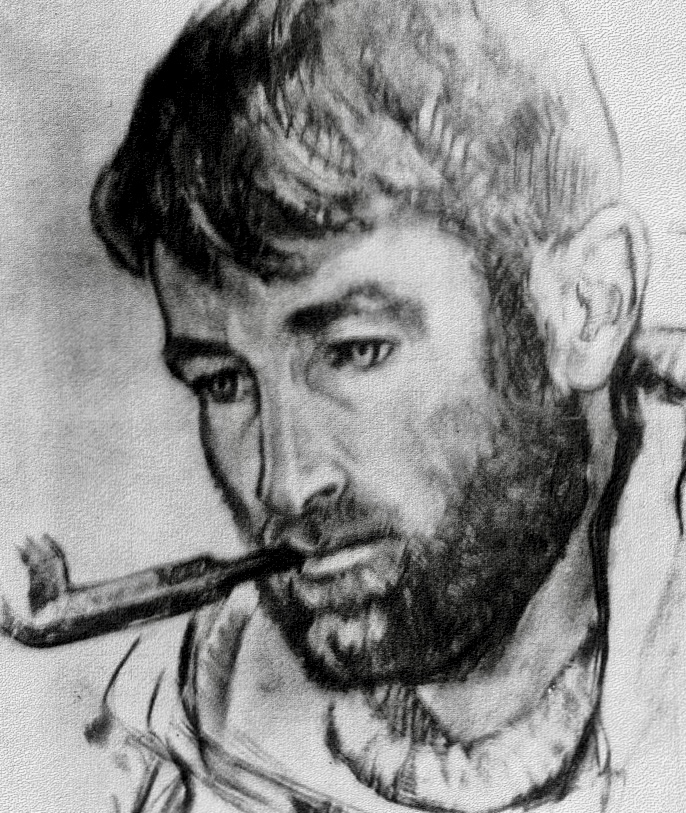

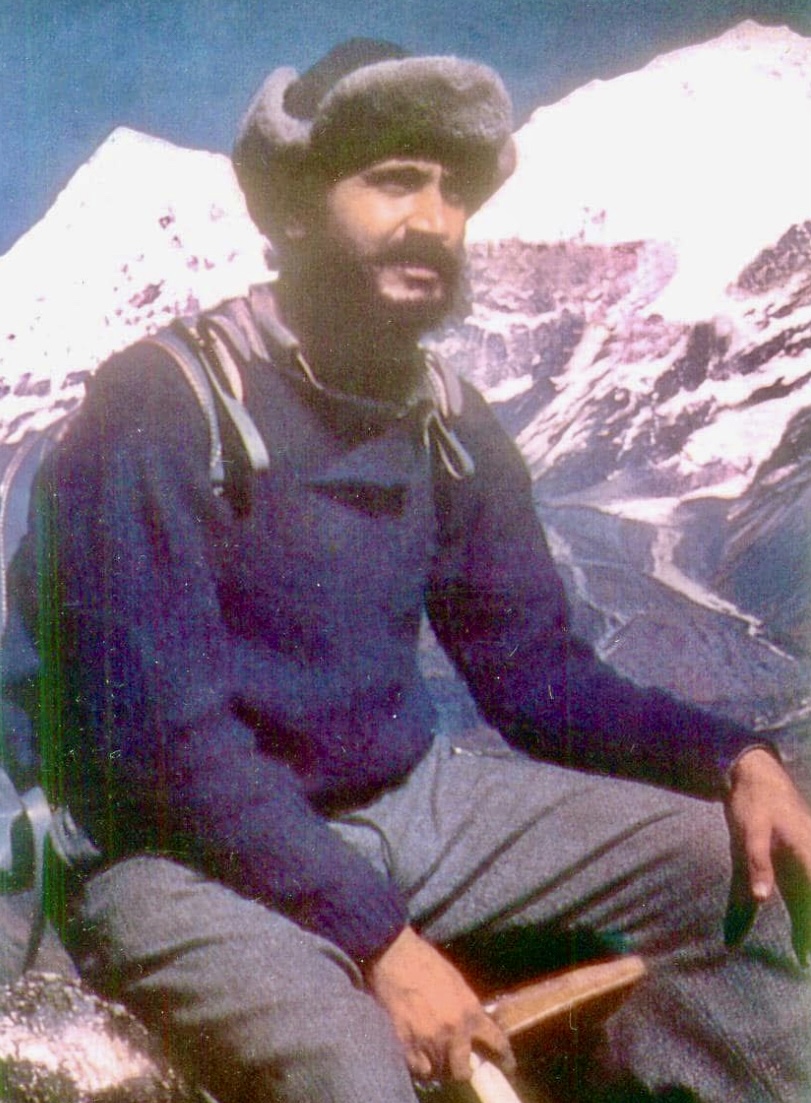

Photo: Kim Chang-ho

Four first ascents of 6,000m peaks

Kim’s explorations in Pakistan led to a series of remarkable solo first ascents in 2003, when he was 33. The American Alpine Journal documents four solo climbs of 6,000m peaks in the Hindu Raj and Karakoram ranges.

He carried out the first ascent of 6,105mm Haiz Kor in the Thui Range of the Hindu Raj, by a challenging route via the southeast face and south ridge through a complex icefall.

Kim also made first ascents of 6,225m Dehli Sang-i-Sar in the Little Pamir, 6,189m Atar Kor in the Hindu Raj, and 6,200m Bakma Brakk in the Masherbrums.

Dehli Sang-i Sar from the southwest, showing the general line of Kim Chang-ho's solo ascent along the upper east ridge in 2003. Photo: Kim Chang-ho

Mastering 7,000’ers

In 2008, he led the first ascent of 7,762m Batura II, though the expedition’s use of fixed ropes drew criticism, prompting him to refine his lightweight approach.

In 2012, Kim and An Chi-young made the first ascent of 7,092m Himjung in Nepal, climbing via its southwest face. The expedition earned them the Piolet d’Or Asia Award.

In 2016, Kim and two partners opened a new 3,800m alpine route on the south face of 7,455m Gangapurna in Nepal. Described by the 2017 Piolet d’Or committee as "bold and lightweight," it earned an Honorable Mention, marking a historic recognition for Korean climbers.

During the Gangapurna expedition, Kim and his partners also attempted the south face of unclimbed Gangapurna West, where they reached the summit ridge.

One year after Gangapurna, the tireless Kim led an expedition to Himachal Pradesh in India, aimed at fostering a younger generation of Korean climbers and developing their skills and experience. The team made the second ascent of 6,446m Dharamsura, and climbed 6,451m Papsura via a direct route on the south face.

Choi Seok-mun and Park Joung-yong, climbing partners of Kim Chang-ho, approach the summit of Gangapurna. Photo: Korean Way Project

Summiting 8,000'ers

Kim summited all 14 of the world’s 8,000m peaks without supplemental oxygen, in record time.

Starting in 2006 with the Busan Alpine Federation’s Dynamic Hope Expedition (led by Hong Bo-Sung), Kim and a small team relied on minimal support, avoiding Sherpas and oxygen. Kim studied geography and history to learn more about his routes.

Kim completed the 14x8,000'ers in 7 years, 10 months, and 6 days, setting a record for the fastest completion without oxygen at the time. He surpassed Jerzy Kukuczka's record by one month.

Kim didn't set out with the explicit goal of climbing the 8,000'ers so quickly. His pursuit was primarily driven by his passion for mountaineering and a desire to climb these peaks in a pure, lightweight style.

Kim ascended three 8,000m peaks twice: Nanga Parbat, Gasherbrum I, and Gasherbrum II.

Among his 8,000m climbs, his south-north traverse of Nanga Parbat in 2005 and his sea-to-summit ascent of Everest in 2013 deserve special mention.

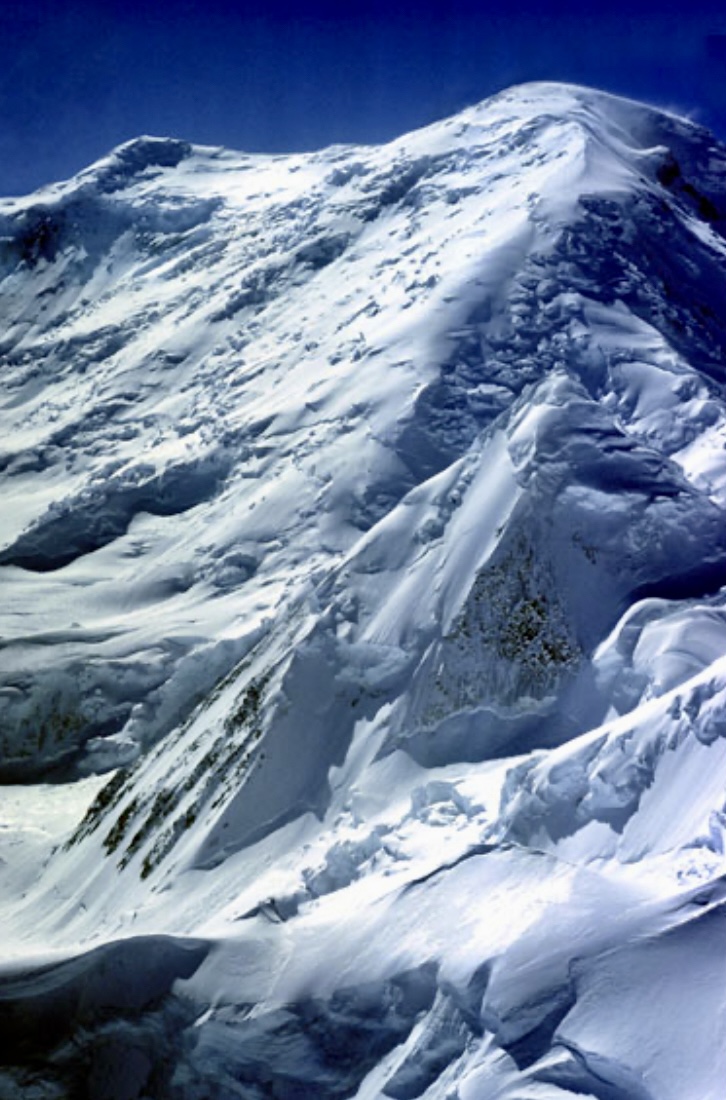

The south face of Gangapurna, showing (in red) the Canadian Route (1981), and (yellow) the Korean Way (2016). Photo: Korean Way Project

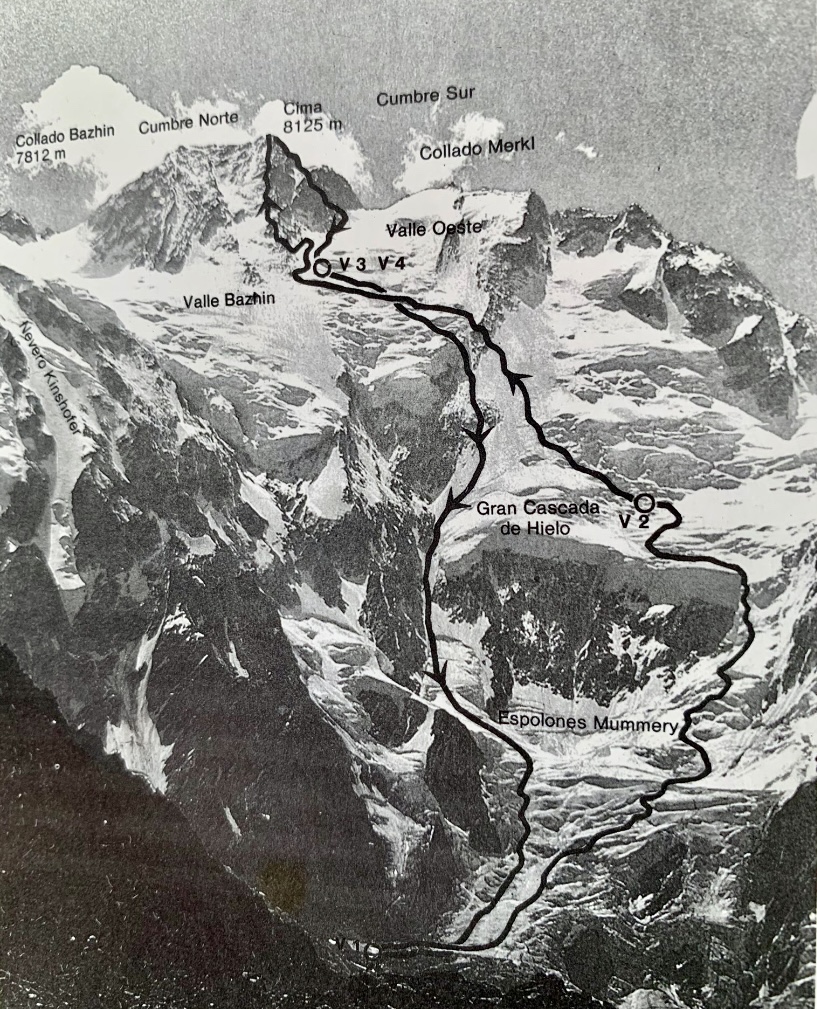

Nanga Parbat, 2005

In 2005, Kim climbed Nanga Parbat’s massive Rupal Face. The Korean Nanga Parbat Rupal Expedition lasted 109 days. They arrived at Base Camp on April 20 after a heavy snowstorm. Over the next 12 days, the team set up Camp 1 at 5,280m and Camp 2 at 6,090m, following a line close to the 1970 Messner Route.

The weather was brutal, with snow falling daily in May, destroying seven tents and burying Camp 2 under fresh snow. Despite these setbacks, by June 14, after 43 days of effort, the team established Camp 3 at 6,850m. Near the end of June, the team prepared for a summit attempt, and on June 26, Kim and three other climbers started their push. However, at 7,550m on the Merkl Icefield, a rock hit team member Kim Mi-gon in the leg, forcing the group to abort.

Undeterred, Kim and climbing partner Lee Hyun-jo made another attempt on July 13, starting from Camp 4 at 7,125m. They faced constant danger, dodging falling rocks and ice. After a 24-hour climb, they reached the summit of Nanga Parbat.

Kim Chang-ho. Photo: Abbas Ali

A difficult descent

Kim and Lee chose to go down the Diamir Face via the Kinshofer Route, unroped, to save time. In the middle of the descent, they triggered a wind slab avalanche. Lee was buried, and Kim was swept 50m downhill, scraping his face and losing his headlamp. Both managed to free themselves and continued down, exhausted and hallucinating, believing another climber was ahead of them. They reached another expedition’s tents at 7,100m but decided against stopping, fearing they might not wake up if they rested. After an incredible 68 hours from Camp 4, they arrived at the Diamir Base Camp, impressing others with their speed and resilience. Lee appeared remarkably fresh despite the ordeal.

This expedition was a turning point for Kim. The climb was a tactical, siege-style effort, relying on fixed ropes and a larger team, very different from the lightweight, alpine-style climbs he later became known for. During the descent, Lee’s emotional radio call to a teammate at Base Camp, expressing regret that they weren’t together, deeply affected Kim.

Kim reflected on his selfishness, realizing that reaching the summit meant little without returning safely with his team. This experience shaped his philosophy moving forward, which would emphasize teamwork, respect for the mountains, and survival over personal glory.

Views of Everest from neighboring Lhotse. Photo: Kadyr Saydilkan

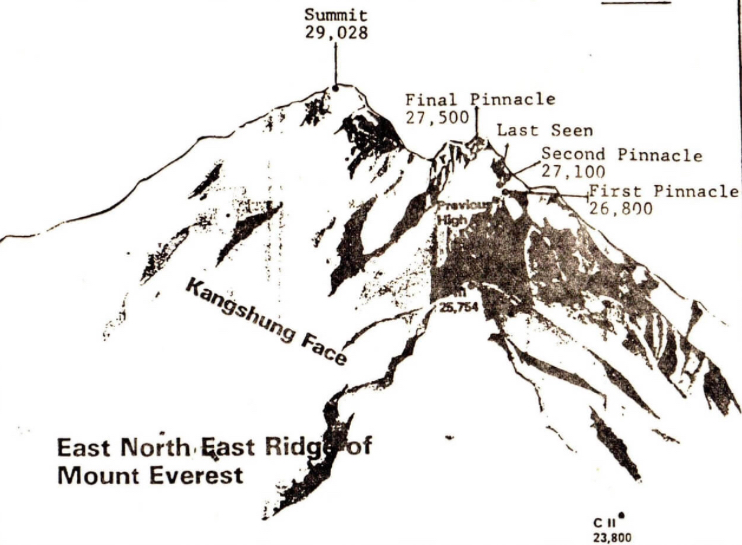

Everest, 2013: Starting from sea level

Kim’s 2013 Everest ascent was the final step in his quest to climb the 8,000m peaks without supplemental oxygen, making him the first Korean to do so. But his Everest climb was not just about reaching the top; it was a unique adventure.

Kim’s journey to Everest’s summit began far from the mountain itself. He wanted to make the climb special by starting at sea level and traveling to Base Camp without using motorized transport.

On March 20, 2013, he began his expedition from Sagar Island near Kolkata, India. From there, he kayaked 156km on the River Ganges, cycled 893km through northern India to Tumlingtar in Nepal, and then trekked 162km to Everest Base Camp. This sea-to-summit approach was rare and challenging, inspired by earlier climbers like Tim Macartney-Snape and Goran Kropp, but Kim added a twist by kayaking part of the way.

Once at Everest Base Camp, Kim prepared to climb the mountain via the standard Southeast Ridge route from the Nepal side without oxygen. He moved steadily up the mountain, navigating the Khumbu Icefall, the Western Cwm, and the steep slopes leading to the South Col. On May 20, Kim reached the summit.

Sadly, Kim’s climbing partner, Seo Sung-ho, died during the descent. This loss cast a shadow over the triumph, but Kim’s accomplishment remained a mountaineering landmark.

Kim Chang-ho and his team near the Sara Umga La at 5,020m, west of Dharamsura and Pasura peaks, in 2017. Photo: Korean Way Project

Mountaineering philosophy

Kim’s mountaineering philosophy viewed climbing as a means of learning and coexistence, not conquest. He avoided treating peaks as mere challenges, instead choosing routes with historical or cultural significance. After losing his partner Seo Sung-ho on Everest in 2013, Kim founded the Korean Himalayan Fund to support young climbers in creative ascents. His database, preserved by his wife Kim Youn-kyoung, includes detailed notes on geography and local names.

Kim’s death

Kim’s life ended on October 11, 2018, when an avalanche, possibly triggered by a serac collapse, destroyed his team’s Base Camp beneath 7,193m Gurja Himal, located south of Dhaulagiri VI, in Nepal. The Korean Way Project expedition, aiming for a new route on the south face, included five South Korean climbers and four Nepali guides, all of whom perished.

Kim’s journal, ending on October 10, suggests the tragedy struck overnight. By the time of his death, he was recognized as South Korea’s most accomplished climber. Kim was 49 years old.

His legacy endures through his database, the Korean Himalayan Fund, climbers like Oh Young-hoon who carry forward his vision, Kim’s daughter (Danah, born in 2016), his wife, and through the international mountaineering community, who preserve his memory.

Kim Chang-ho. Photo: En.namu.wiki

On July 11, 1985, Pierre Gevaux made the first paragliding descent from the summit of an 8,000m peak, soaring down from 8,034m Gasherbrum II. This groundbreaking feat opened a new chapter in mountaineering history.

Gevaux was part of a French expedition to Pakistan led by Claude Jaccoux. It included clients, three guides, and two high-altitude porters. They shared Base Camp with another French team led by well-known mountaineer and extreme adventurer Jean-Marc Boivin.

The expedition began in early July, with climbers establishing camps along the standard route. On July 11, Gevaux and the other team members topped out. The summit day featured clear weather, offering a rare window for his paragliding descent.

Paragliding technology was in its infancy, and Gevaux’s paraglider was likely a basic or parachute-like canopy. It required significant skill to control, especially in the thin air and unpredictable winds at such an extreme altitude.

According to Xavier Murillo, Gevaux's first two attempts to fly from the summit failed. Each time he had to climb back up, catch his breath, gather his thoughts, and tell himself that he would be able to do it. The third time was the charm.

The descent covered a vertical drop of several thousand meters to Camp 1 at 6,000m. He reached it in 5 minutes and 45 seconds. It had taken him five months of preparation, two months on the expedition, and four days of climbing.

Gevaux’s feat impressed other mountaineers who were on Gasherbrum II that day, including Jean-Marc Boivin.

Boivin paraglides down Everest

Boivin was an adventurer known for his first ascents, ski descents, and pioneering hang gliding and paragliding. He was reportedly inspired by Gevaux’s paragliding descent from Gasherbrum II. On that expedition, Boivin broke a hang glider altitude record when he successfully launched from the summit. Previously, in 1979, Boivin had set a hang glider altitude record when he flew from nearly 8,000m after climbing K2.

Three years after Gevaux’s flight, on Sept. 26, 1988, Boivin achieved the first paragliding descent from just below the summit of Everest. The thin air at 8,848m made launching difficult, and gusty winds required precise timing to ensure a safe takeoff. Boivin’s success cemented his reputation as a pioneer of extreme sports, though he tragically died two years later while BASE jumping off Angel Falls in Venezuela.

You can read more about Everest’s paragliding and hang gliding history here.

Paragliding descents from other 8,000’ers

Gevaux’s 1985 flight and Boivin’s 1988 flight pointed the way for others.

In 1994, Australian Ken Hutt paraglided down from 7,200m on Cho Oyu.

In July 2019, Austrian climber Max Berger paraglided from the shoulder of 8,051m Broad Peak, landing in Base Camp 17 minutes later. Though not from the summit, this descent was a significant high-altitude feat.

On July 19, 2022, French climber Benjamin Vedrines paraglided from Broad Peak’s summit ridge after a speed ascent without supplemental oxygen, landing at Base Camp in about an hour.

On July 28, 2024, French climbers Benjamin Vedrines, Jean-Yves Fredriksen, Zeb Roche, and Liv Sansoz paraglided from the summit of K2 despite a Pakistani paragliding ban. All four had summited without bottled oxygen.

Vedrines -- after claiming a climbing speed record of 10 hours, 59 minutes, and 59 seconds -- launched first, landing at Base Camp in 30 minutes. Fredriksen landed at 6,600m after struggling for 90 minutes to take off, and Roche and Sansoz achieved the first tandem paragliding descent from an 8,000m summit.

Most recently, on June 24 of this year, David Goettler paraglided from 7,700m after summiting Nanga Parbat via the Schell Route on the Rupal Face without bottled oxygen.

In the video below, you can watch Gevaux's pioneering paragliding descent from Gasherbrum II in 1985:

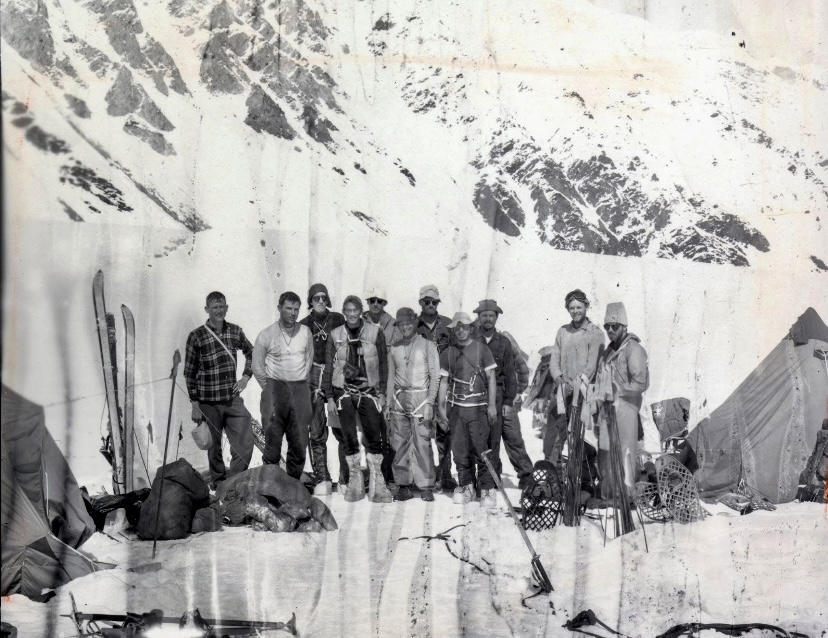

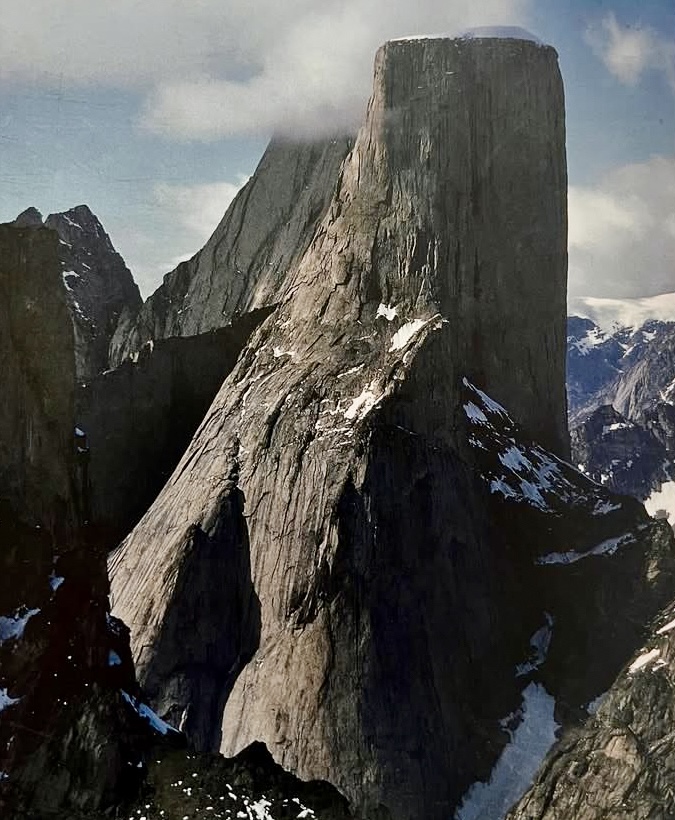

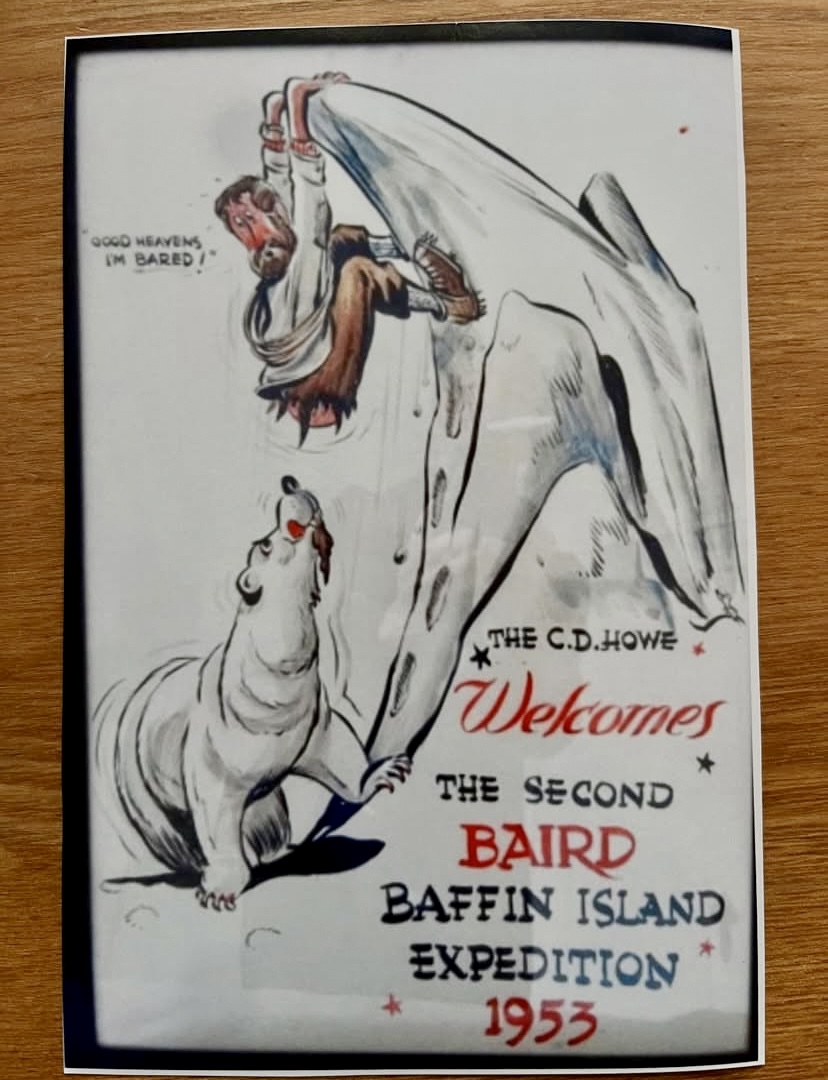

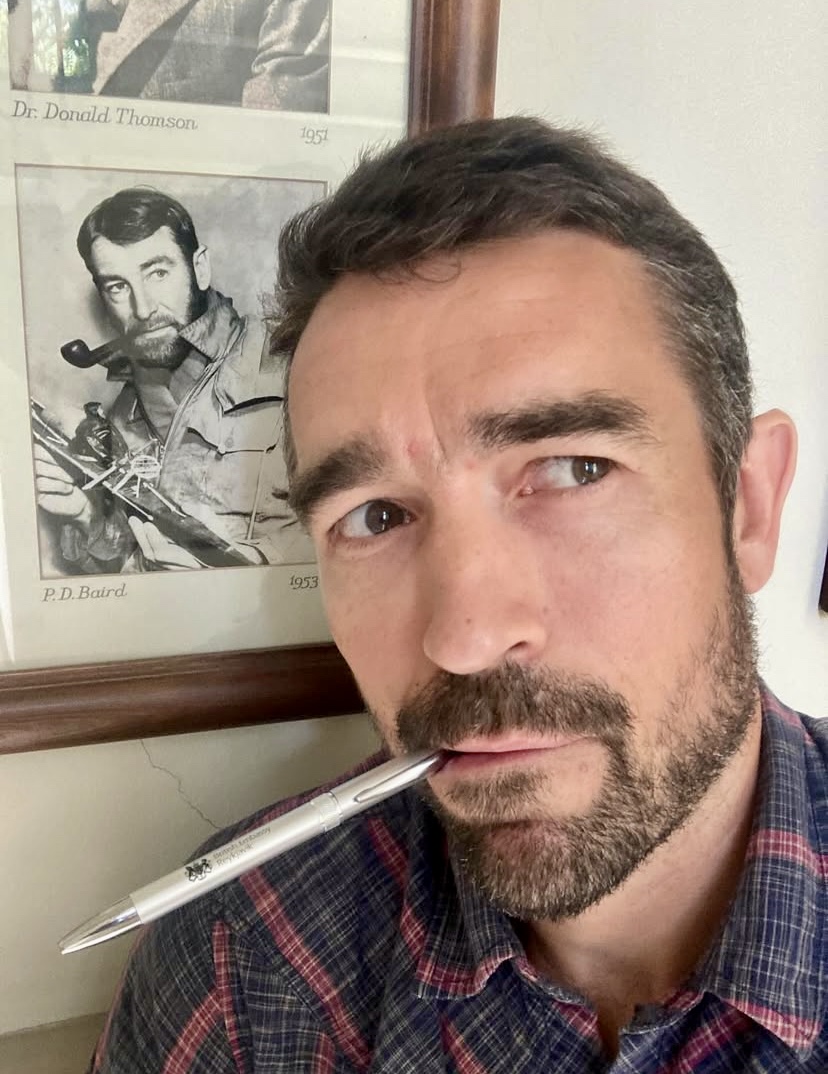

British adventurers Niall McCann and Finn McCann are on their way to climb Mount Asgard, the 2,015m twin-peaked granite tower in Auyuittuq National Park on Baffin Island. It's a family affair: They want to climb the peak that their grandfather, Patrick Douglas Baird, named but never summited.

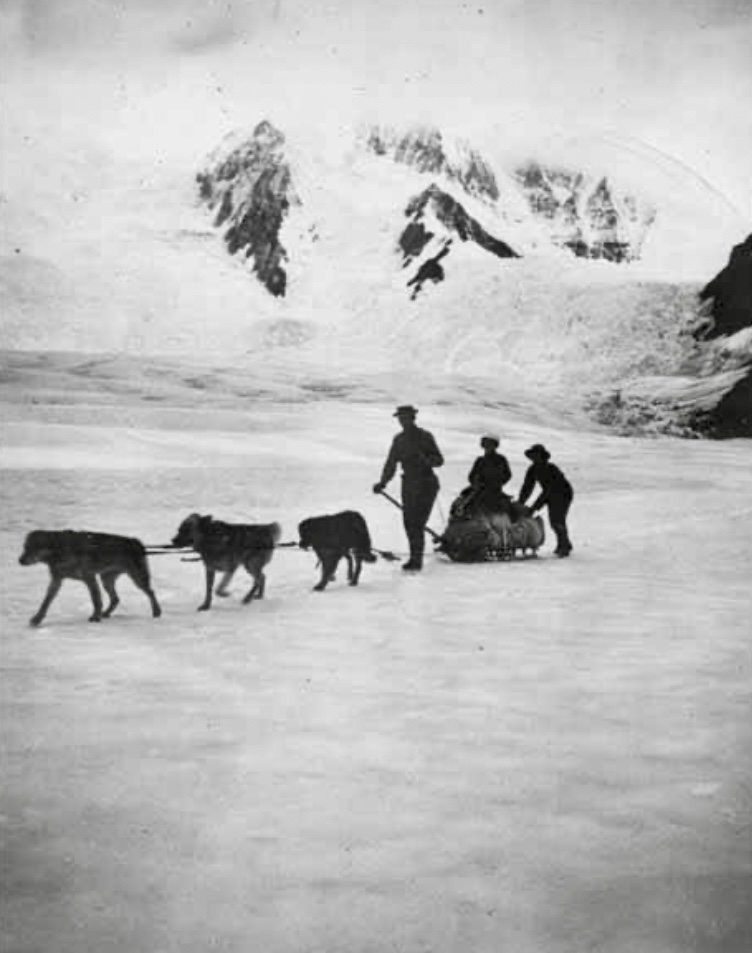

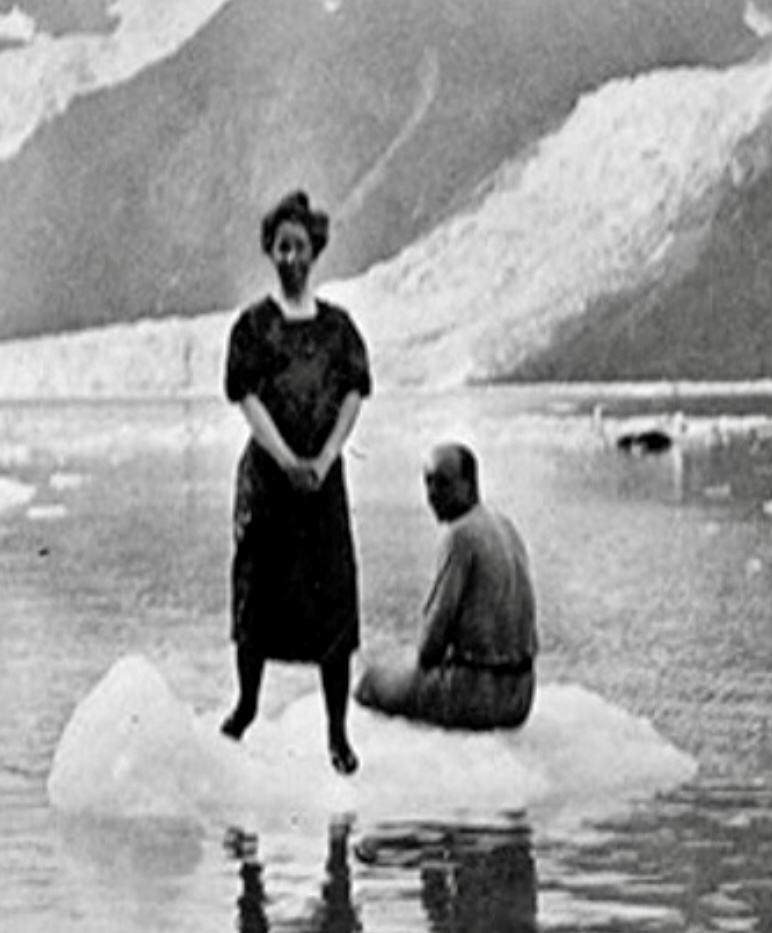

The McCanns will arrive shortly in Pangnirtung, the gateway to that Canadian Arctic national park. Here, they will share 1953 photos with local residents to connect with those who may recall Patrick Douglas Baird. They will then haul 40kg loads to the base of the mountain and climb the tower over about three weeks.

In an Instagram post, Niall McCann recounted Patrick Douglas Baird’s 1953 expedition: “In the summer of 1953, my grandfather Pat Baird led a four-month expedition...for the Arctic Institute of North America. During this expedition, he first laid eyes on an extraordinary-looking mountain, which he named Asgard (subsequently changed to Mount Asgard), home of the gods.”

The jagged, fiord-indented east coast of Baffin Island features some of the highest cliffs in the world. The highest peak is Mount Odin (2,147m), followed by Mount Asgard (2,015m), Mount Qiajivik (1,963m), Angilaaq (1,951m), Kisimngiuqtuq (1,905m), Ukpik (1,809m), Bastille Peak (1,733m), Mount Thule (1,711m), Angna (1,710m), and Mount Thor (1,675m). There is also a whole other area further north with slightly lower but equally world-class cliffs in Sam Ford Fiord, where the walls rise directly from the ocean. In short, eastern Baffin offers amazing climbing.

The two towers

Mount Asgard lies inland on southeastern Baffin Island. Its granite north and south towers, separated by a saddle, soar 1,600m above the valley, making it a premier big-wall destination. Of the two towers, the north one is slightly taller than the south.

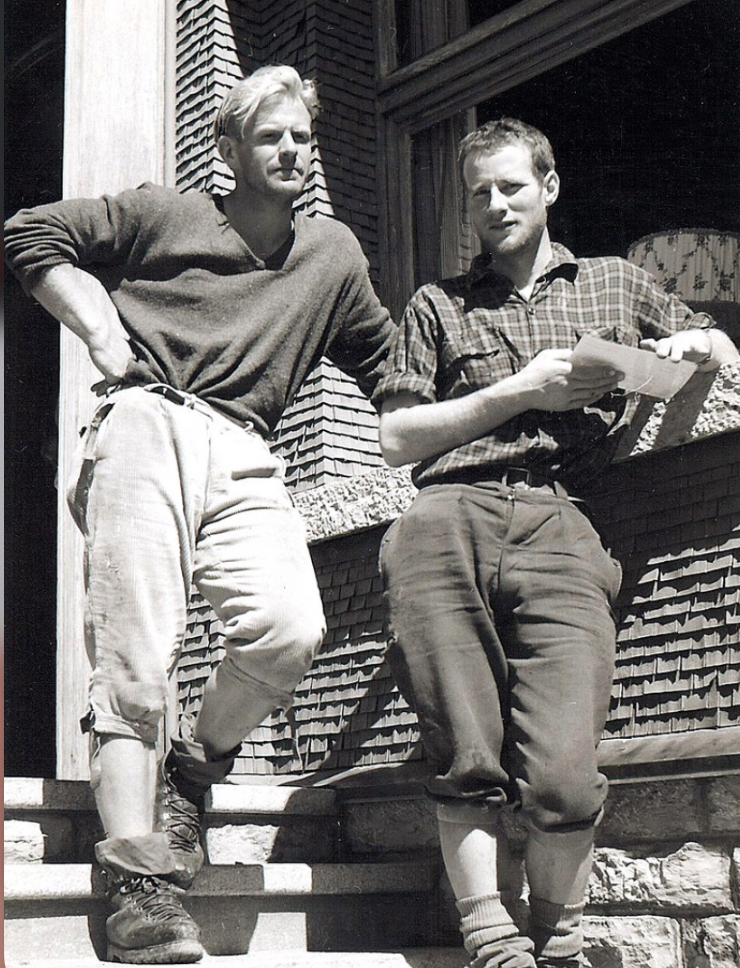

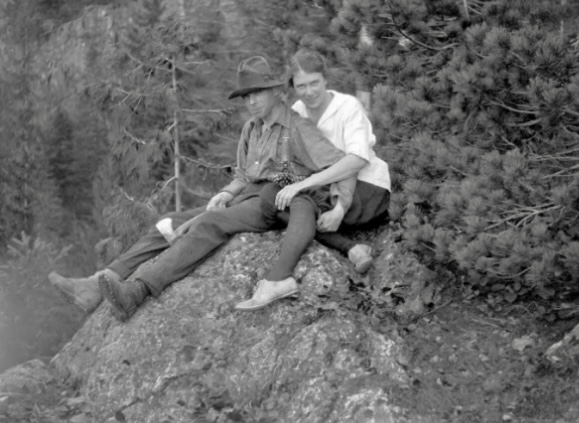

In 1934, Patrick Douglas Baird explored Greenland and northeastern Baffin Island. In 1938, he returned to Baffin, only to lose his companion when a storm blew him out to sea, to a watery grave.

Although he never summited the peak, Patrick Baird was an important figure in the climbing history of Asgard. It began in 1953 during the Arctic Institute expedition, which he led. Four Swiss scientists -- Jurg Marmet, Hans Rothlisberger, Fritz Hans Schwarzenbach, and Hans Weber -- father of polar traveler Richard Weber -- made the first ascent. They reached the Asgard saddle from the east, then summited the north peak. Baird put up several first ascents during that four-month expedition, but he himself didn’t join the Asgard climb.

In 1963, Baird led another successful expedition to Mount Asgard. His 14-year-old daughter, Niall and Finn McCann’s mother, was a team member. Baird again did some notable first ascents in the area but did not climb Asgard.

A climbing party, led again by Baird, made the first ascent of the 2,000m South Tower in 1971. Doug Scott, Guy Lee, Rob Wood, and Phil Koch summited via the 1,000m south ridge. They then made an epic descent in a blizzard. In 1972, Scott returned to Baffin Island with Dennis Hennek, Paul Nunn, and Paul Braithwaite, this time without Baird, and established the Scott-Hennek Route on the East Pillar of Asgard.

More on Pat Baird

Patrick Douglas Baird was born in the UK in 1912 and became a key figure in latter-day Arctic exploration. He studied geography and geology at Cambridge University. Then in the 1930s, he joined the British Arctic Air Route Expedition to Greenland (1930–1931) and led the Cambridge East Greenland Expedition in 1934. He also directed a 1936–1937 expedition to Baffin Island, where he did mapping and studied glaciers.

During World War II, Baird served as an instructor at the Canadian Army’s winter warfare school, training soldiers for cold-weather combat. In 1947, he became Director of the Arctic Institute of North America, guiding research and serving on the institute’s Board of Governors.

Baird wrote many scholarly articles on Arctic geography and glaciology. He also authored The Polar World in 1964 and co-wrote Field Guide to Snow and Ice with W.H. Ward. Baird died in Ottawa in 1984, and his ashes were scattered on Baffin Island. You can read more about Pat Baird here.

The McCann brothers

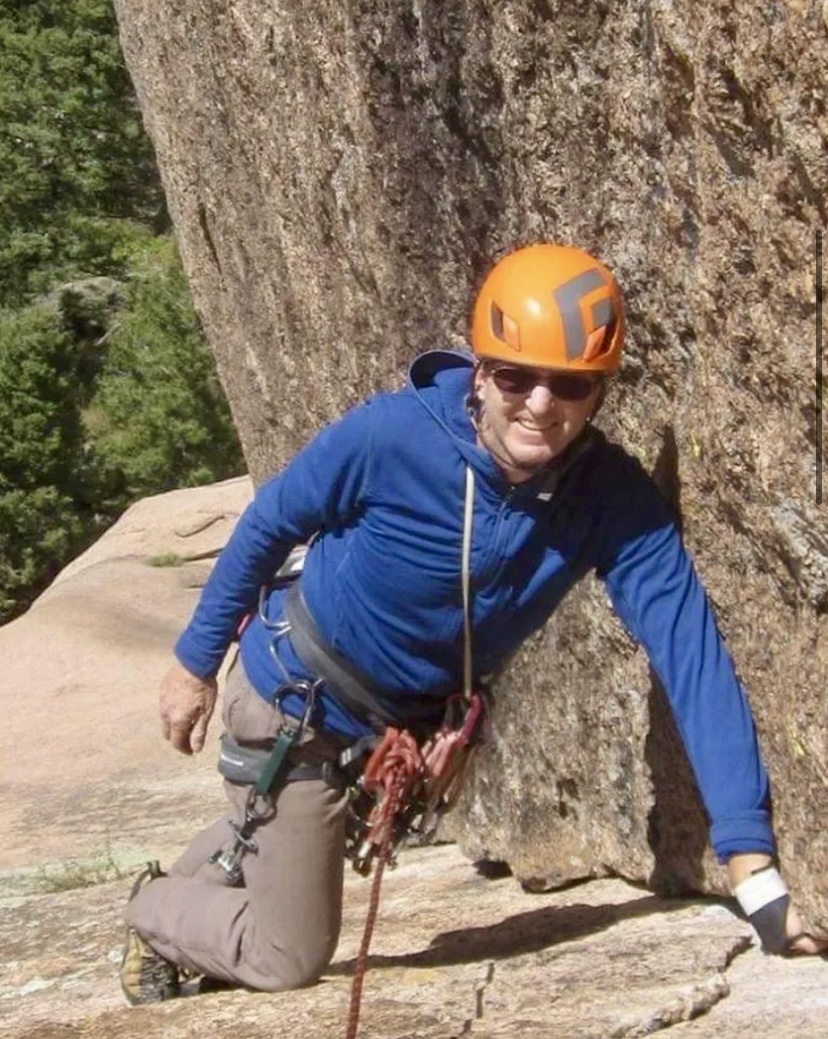

Niall McCann, a biologist, National Geographic Explorer, and Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society, has extensive experience in big-wall climbing in the U.S. and Europe. He has also done ski-mountaineering in Greenland.

Finn McCann brings over 20 years of climbing experience across more than 30 overseas expeditions, including Himalayan ascents, technical Alpine mixed routes, and multi-day big walls. He also participated in the 2014 Greenland expedition with his brother.

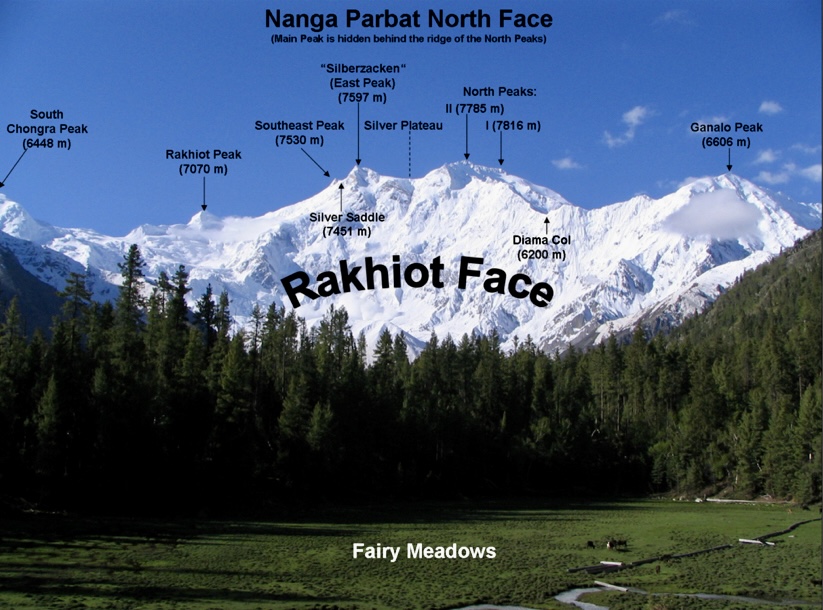

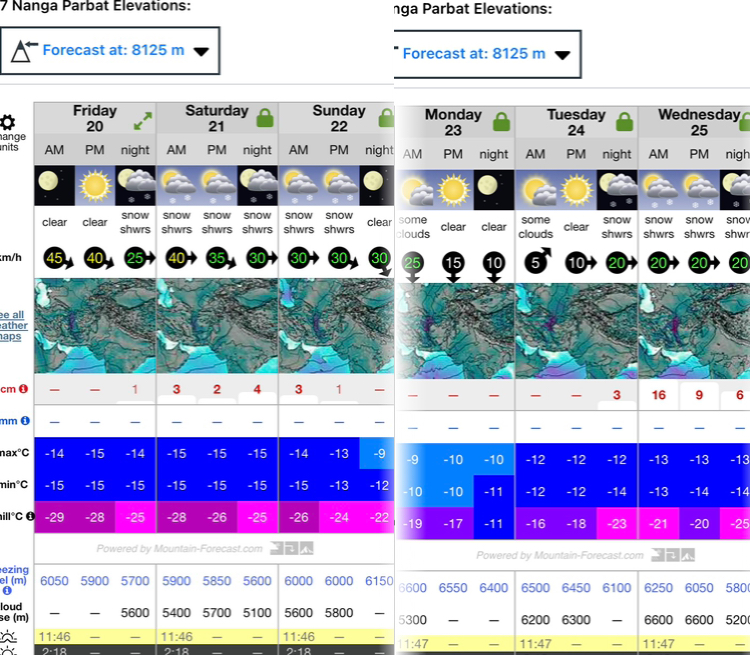

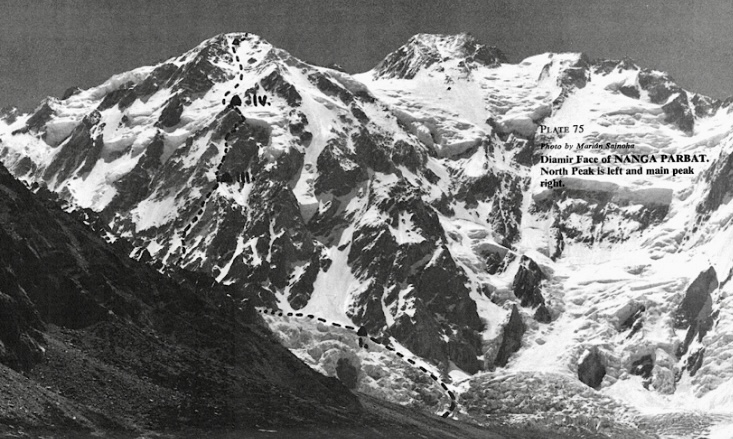

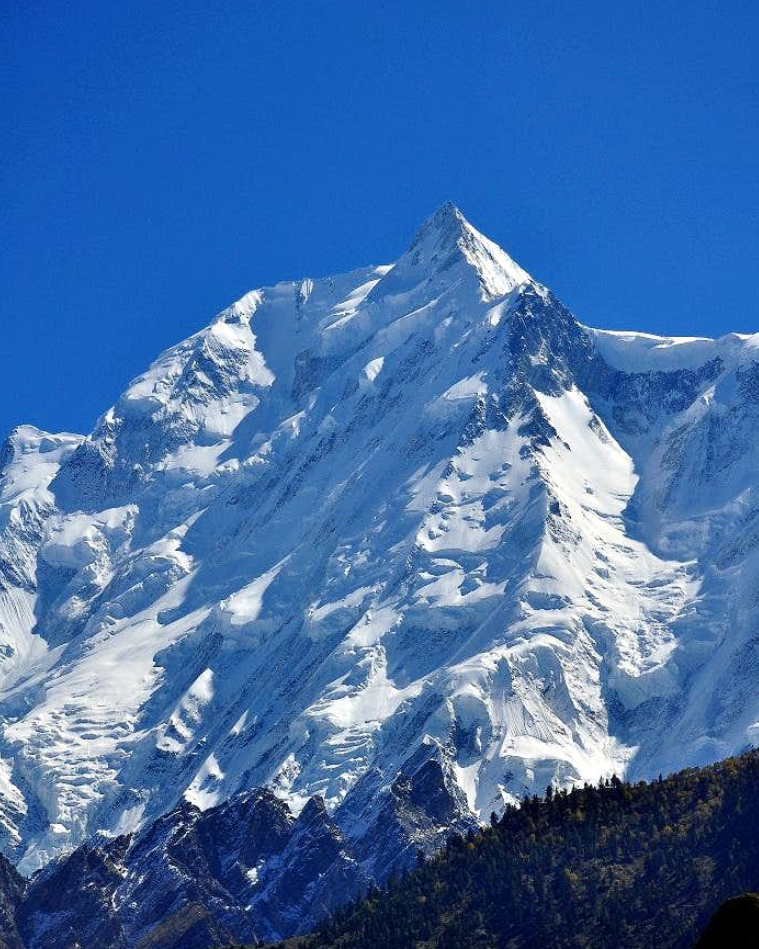

At 8,125m, Nanga Parbat in Pakistan’s Gilgit-Baltistan is the world's ninth-highest mountain, and it is dangerous. It earned its "Killer Mountain" nickname because of the high fatality rate during its early climbing history.

It has three main faces: the south-facing Rupal Face, the northeast-facing Rakhiot Face, and the northwest-facing Diamir Face. The Rakhiot Face is less frequently climbed than either the Diamir or Rupal Faces.

Only three teams have successfully ascended the Rakhiot Face, but more than 30 climbers have died.

The first fatalities

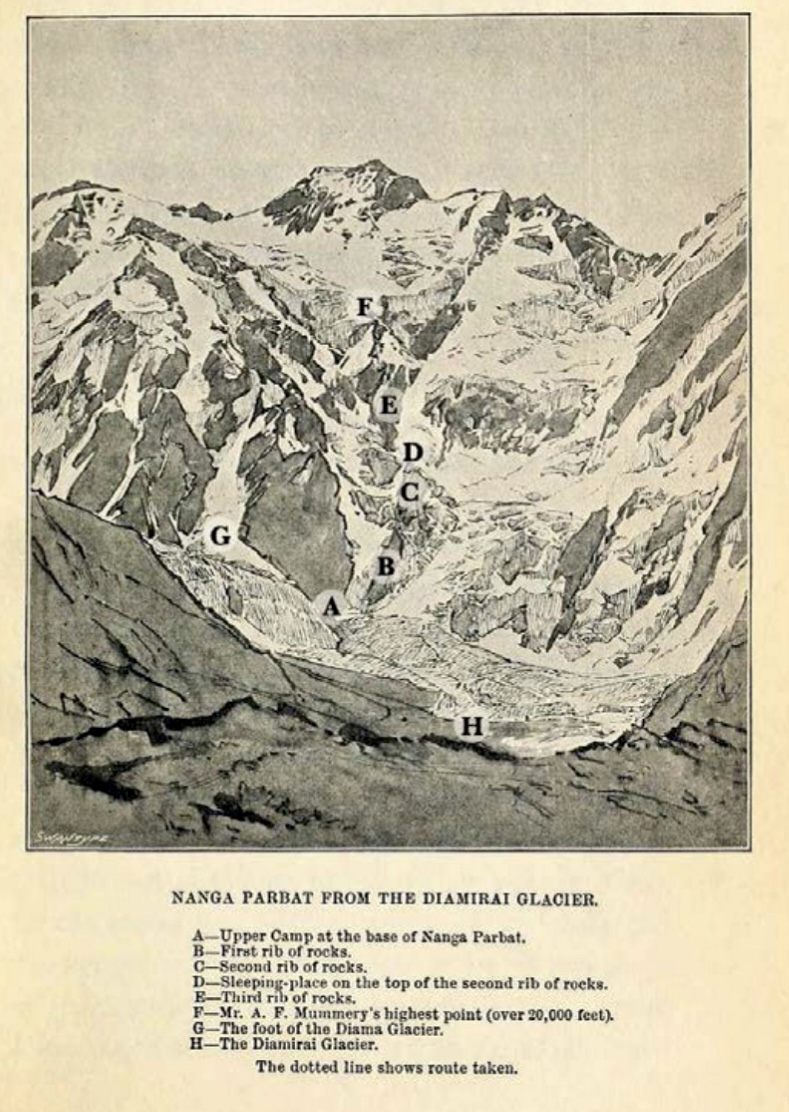

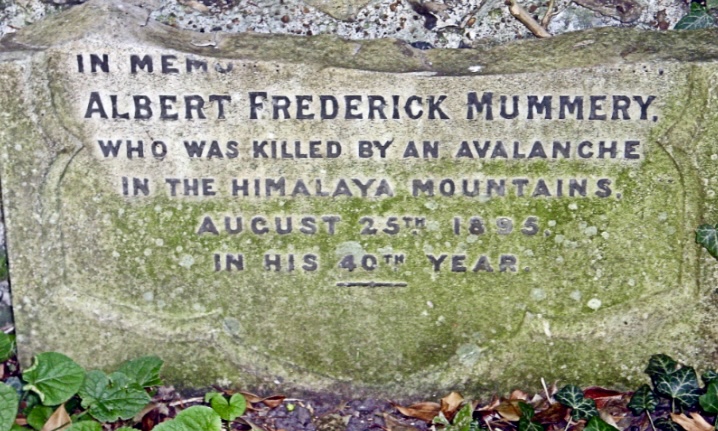

In 1895, Albert Mummery, Ragobir Thapa, and Goman Singh died while scouting the Rakhiot Face. They’re presumed to have died in an avalanche or fall, as their bodies were never found.

German expeditions

The Rakhiot Face became a focal point in the 1930s, particularly for German climbers, as Nanga Parbat was one of the few 8,000’ers accessible to non-British expeditions because of restrictions on Everest and the remoteness of K2.

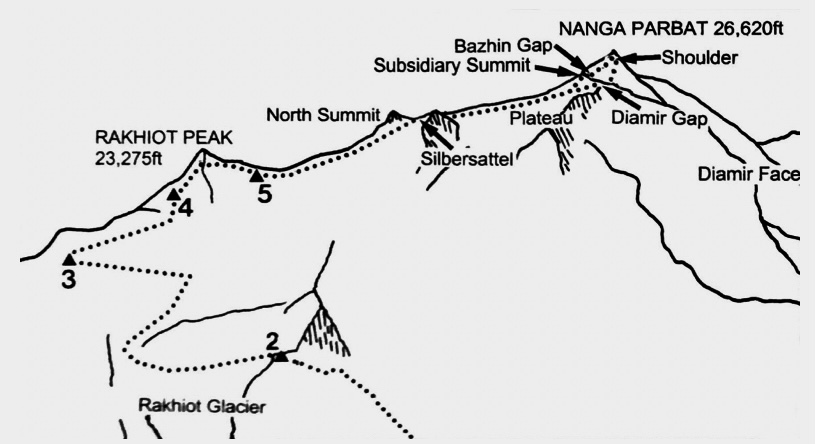

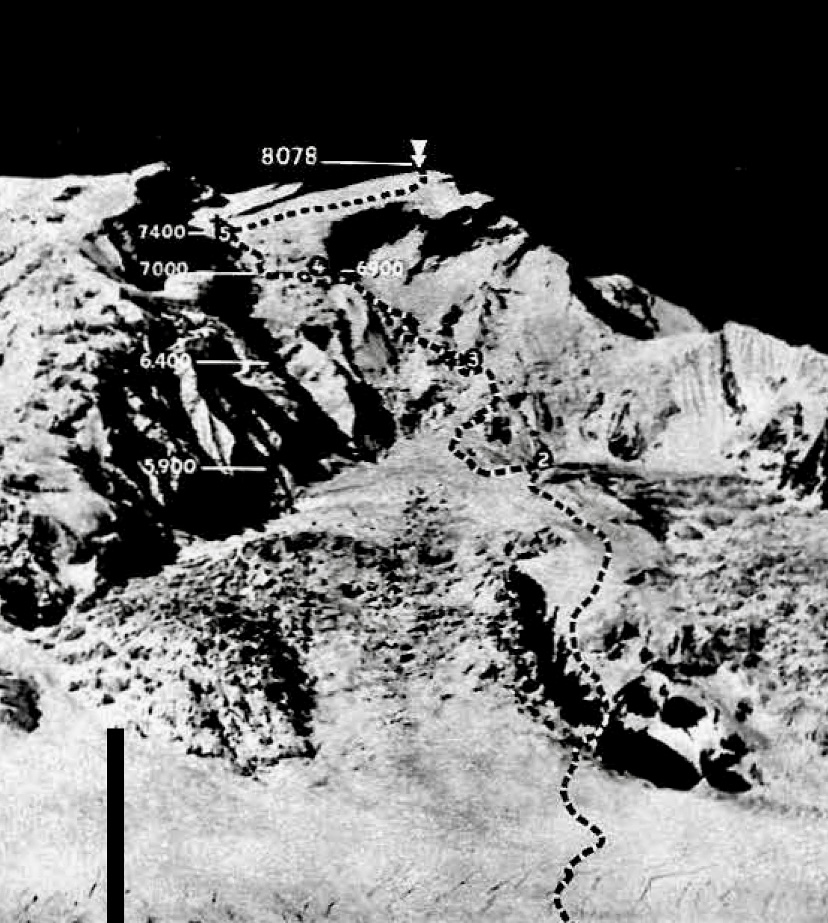

The face, characterized by the Rakhiot Glacier, Rakhiot Peak (7,070m), the Silver Saddle (7,400m), and a long ridge to the summit, presented a viable but hazardous route due to its length and exposure to avalanches and storms. The expeditions of this era targeted what would later be known as the Buhl Route, which contributed both to the mountain’s allure and its deadly reputation.

1932: Willy Merkl’s German-American expedition

The first significant attempt on the Rakhiot Face was in 1932, led by German climber Willy Merkl. The expedition, sometimes called German-American because of the inclusion of American climbers Rand Herron and Fritz Wiessner (Wiessner was German-born but became a U.S. citizen), aimed to establish a route via the Rakhiot Glacier and Rakhiot Peak.

Merkl’s party took a route to the left of the Northeast Ridge, which involved steep ice and rock. But they lacked Himalayan experience, and poor planning hampered their progress. They did not have enough porters, and bad weather added to their problems.

Peter Aschenbrenner and Herbert Kunigk reached 7,070m Rakhiot Peak but could not progress further. However, the expedition confirmed the feasibility of a route via Rakhiot Peak and the main ridge.

1934: Merkl’s second attempt

Merkl returned in 1934 with a better-prepared expedition, funded by the Nazi government. They targeted the same Rakhiot Face route as in 1932, with a minor variation.

Early in the expedition, climber Alfred Drexel died, likely from high-altitude pulmonary edema. Things only deteriorated from there.

Fierce storms caused chaos on the mountain. On July 6, Peter Aschenbrenner and Erwin Schneider reached 7,895m, one of the highest points ever attained at the time, but worsening weather forced them back.

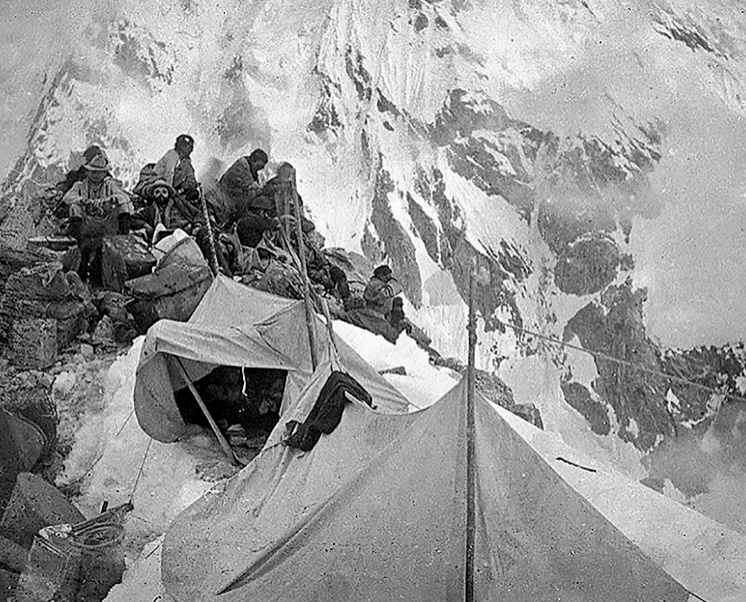

On July 7, a ferocious storm trapped 14 team members at 7,480m near Camp 4, below Rakhiot Peak. This led to the deaths of Merkl, Willo Welzenbach, Uli Wieland, and six porters: Pintso Norbu, Nima Norbu, Dorje Sherpa, Tashi Sherpa, Dakshi Sherpa, and Gaylay Sherpa. The 1938 Nanga Parbat expedition found their bodies.

At the time, it was the deadliest mountaineering disaster in history. This tragedy, alongside later disasters, cemented Nanga Parbat’s Killer Mountain reputation.

1937: Karl Wien’s avalanche disaster

In 1937, another German expedition targeted the same route.

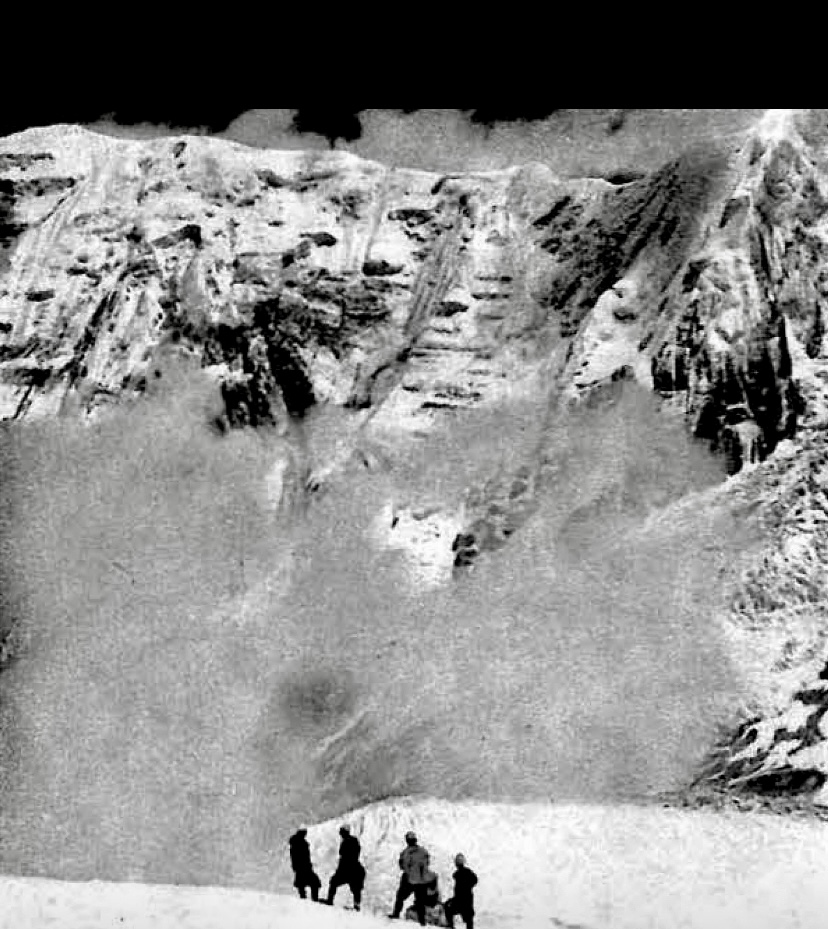

Led by Karl Wien, the team made slow progress because of heavy snowfall. On the night of June 14, a huge avalanche from the hanging glacier on Rakhiot Peak hit them in Camp 4. The avalanche rushed 1,200m across the flat terrace where their camp was set up, burying the tents under meters of ice and packed snow. The campsite was considered safe previously, but a sudden change in weather likely triggered the avalanche.

The avalanche killed seven German climbers (Wien, Hans Hartmann, Adolf Goettner, Martin Pfeffer, Gunther Hepp, Peter Mullritter, and Otto Fankhauser) and nine support staff members (Pasang P., Nim Tsering, Mambahadur, Kami, Gyaljen Monjo, Jigmay, Chong Karma, Ang Tsering II, and Da Thondup).

A search team led by Paul Bauer later found the tents buried under ice and snow, with one climber’s diary noting the camp’s unsafe position. Five bodies were found buried nearby. Described as having "no parallel in climbing annals" for its prolonged suffering, this disaster added to the Rakhiot Face’s deadly reputation.

1938: Paul Bauer’s cautious attempt

Paul Bauer led a German expedition in 1938, mindful of the 1934 and 1937 tragedies.

The team reached the Silver Saddle, halfway between Rakhiot Peak and the summit, but bad weather forced a retreat. Heinrich Harrer, a member of the expedition, noted the face’s challenging conditions. No fatalities occurred, but the expedition made no significant progress beyond previous attempts.

1939: Harrer’s reconnaissance

In 1939, Harrer joined a German expedition led by Peter Aufschnaiter, primarily to scout the Diamir Face. However, they also examined the Rakhiot Face, concluding that it was a viable but dangerous route. World War II and their internment in British India halted further attempts.

The 1930s saw five German expeditions to the Rakhiot Face, with at least 25 deaths and no successful ascents, underscoring its lethality.

1950: the British winter reconnaissance

The first documented winter attempt on Nanga Parbat occurred in December 1950, when a three-member British team of William Crace, John Thornley, and Robert Marsh scouted the Rakhiot Face.

Marsh descended with frostbiten toes, leaving Crace and Thornley in a tent at 5,500m. Both disappeared, likely swept away by an avalanche or caught in a storm.

"Thornley and Crace were both extremely determined," Marsh wrote for the Himalayan Club. "Thornley, for instance, marched 265km to Nanga Parbat over the Babusarr Pass, wearing a pair of gym shoes, in six days, and was in no way fatigued at the end. They were a fine pair of friends, and it took an expedition of this sort, where we lived close, in difficult conditions, to bring out fully the great qualities of endurance, patience, and kindness which were so characteristic of them. I am sure they wish for no better tribute than that. When they were last seen, they were still going up and still going strong."

1953: Nanga Parbat’s first ascent

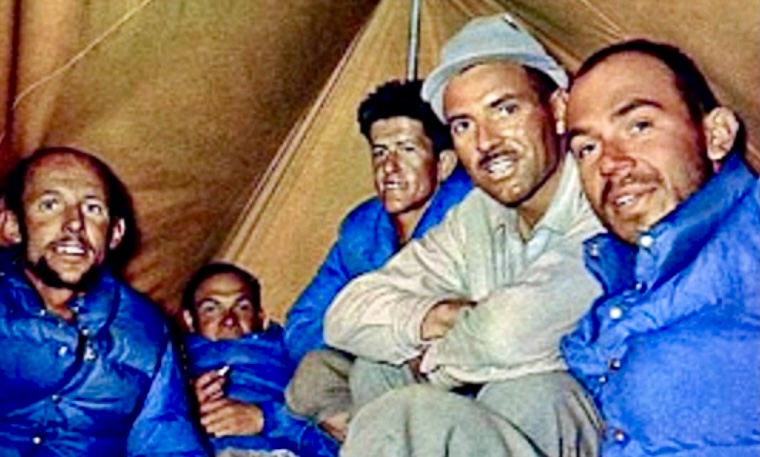

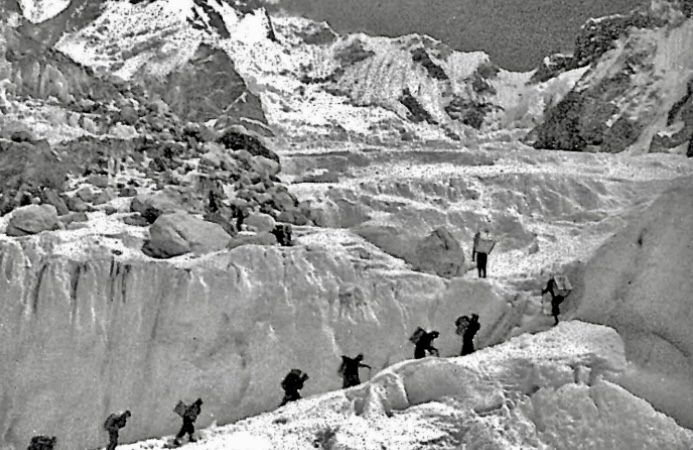

The first successful ascent of Nanga Parbat was in 1953 via the Rakhiot Face. The German-Austrian expedition was led by Karl Maria Herrligkoffer (who did not climb), whose half-brother Willy Merkl had died in 1934.

The team included Austrians Hermann Buhl, Peter Aschenbrenner, Walter Frauenberger, and Kuno Rainer, plus Germans Otto Kempter, Hermann Kollensperger, Albert Bitterling, Fritz Aumann, and Hans Ertl. It also included several (unnamed in the literature) local porters who carried supplies to Base Camp and up to Camp 4.

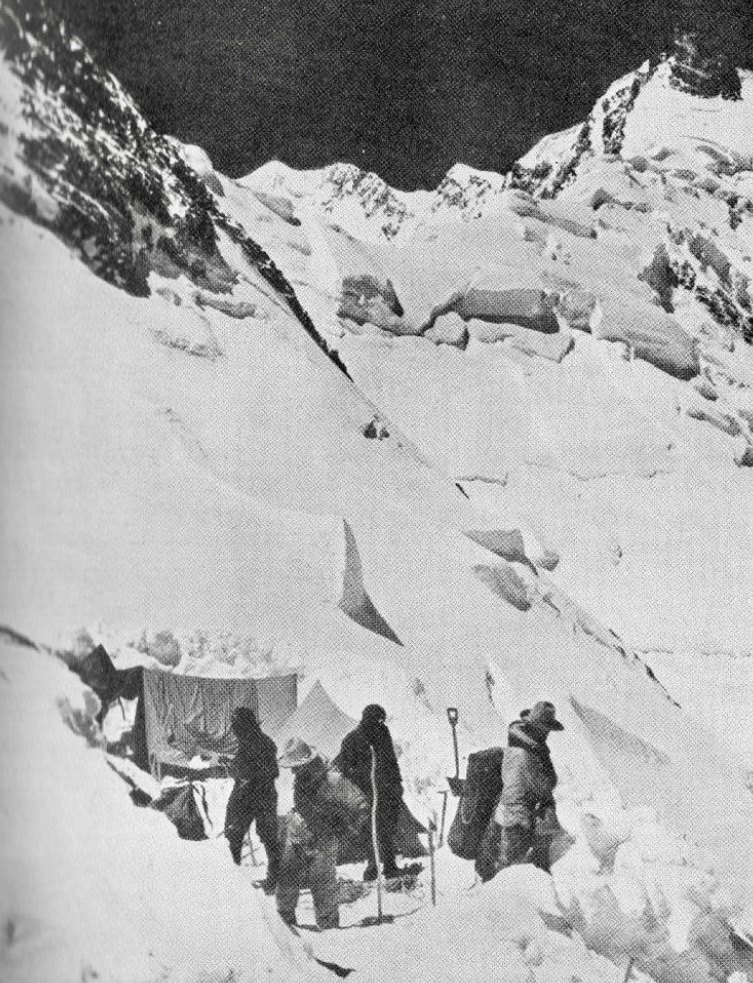

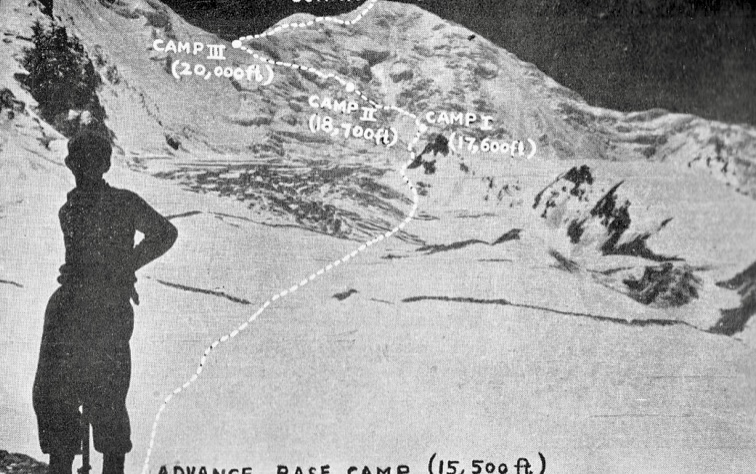

The expedition followed what became the Buhl Route: starting at the Rakhiot Glacier with Base Camp at 3,967m, ascending to Rakhiot Peak, traversing the Silver Saddle, and climbing the North Ridge to the summit.

On May 24, the expedition reached Base Camp. On June 10, Buhl, Kollensperger, and porters set up Camp 2 at 6,200m on the Rakhiot Glacier. Two weeks later, the climbers and porters established Camp 4 at 6,700m, below Rakhiot Peak.

On July 1, Buhl, Kempter, Frauenberger, and Ertl set up Camp 5 at about 6,950m with porter support. The porters then returned to the lower camps.

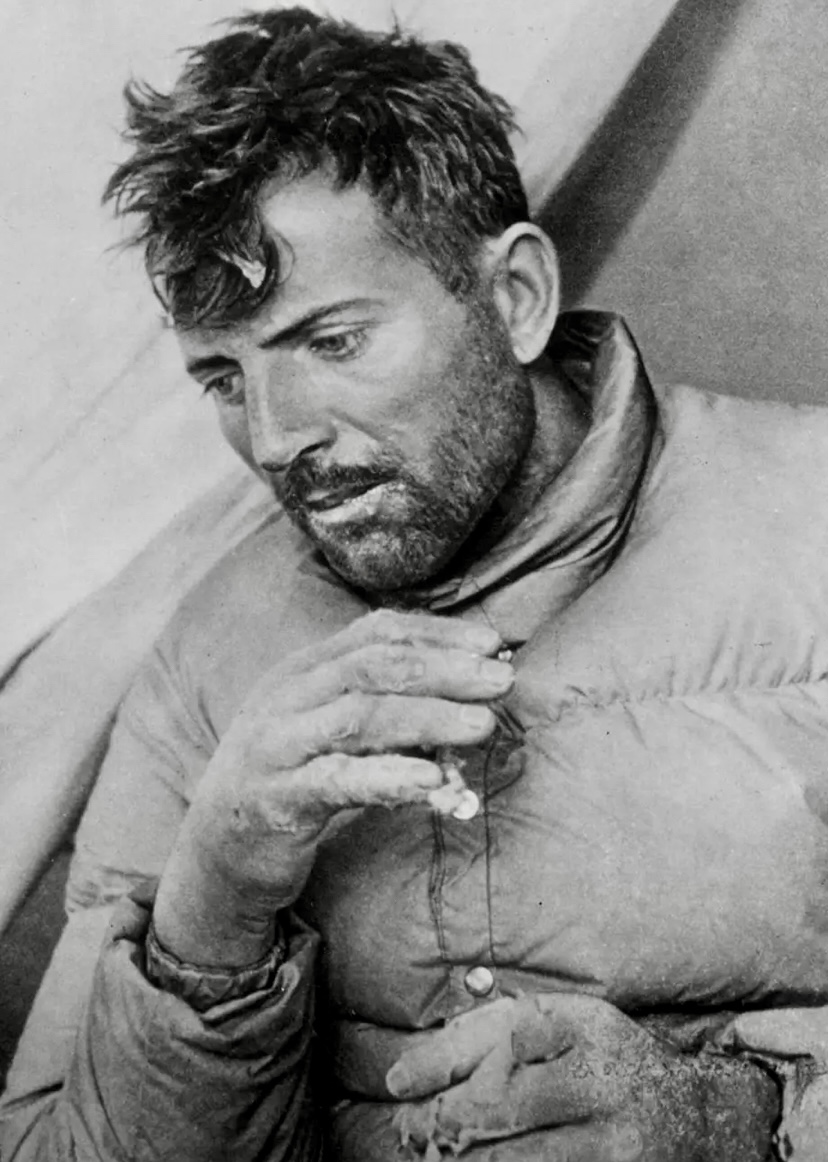

Hermann Buhl’s solo summit push

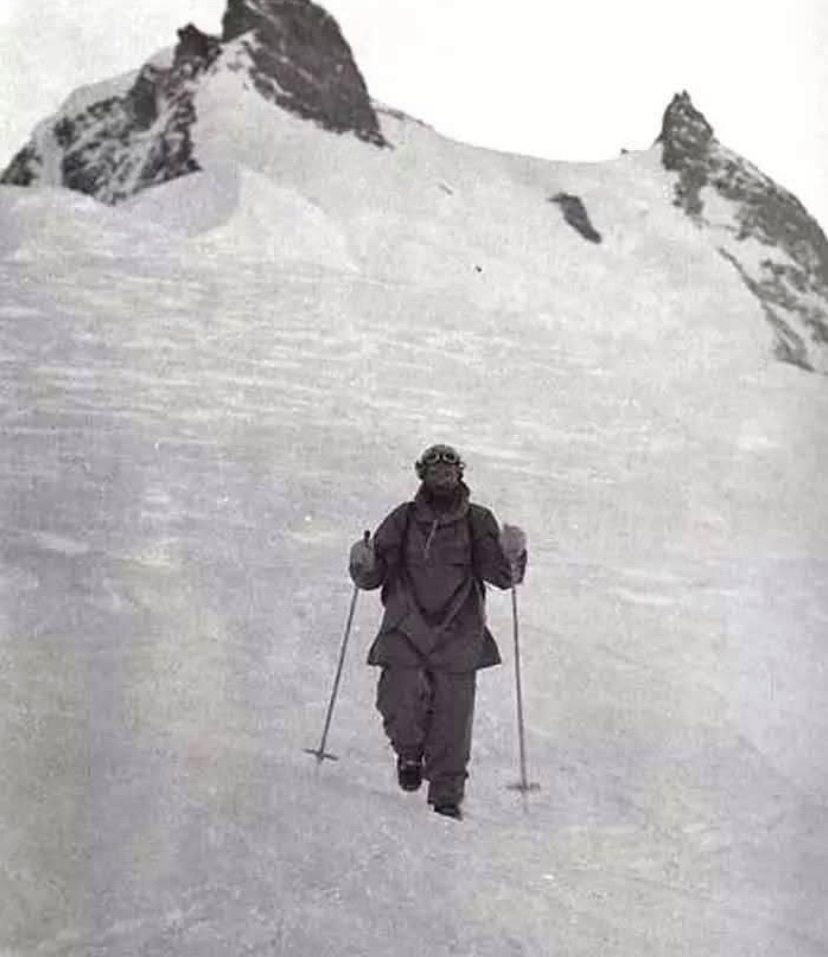

On July 2, Buhl and Kempter stayed at Camp 5 before Kempter turned back. After delays and disagreements, Aschenbrenner, the climbing leader of the expedition, ordered a retreat because of the approaching monsoon. Buhl, determined to summit, continued alone.

On July 3 at 2 am, Buhl started his summit push, carrying food, a flag, some pervitin and padutin pills, but no rope and no supplemental oxygen. His solo push was in alpine style.

Pervitin was a drug containing methamphetamine, a powerful stimulant. It was widely used by the German military during World War II to enhance alertness and relieve combat fatigue. Padutin improves blood circulation and prevents frostbite by dilating blood vessels. Yet despite the pills, Buhl did suffer frostbite.

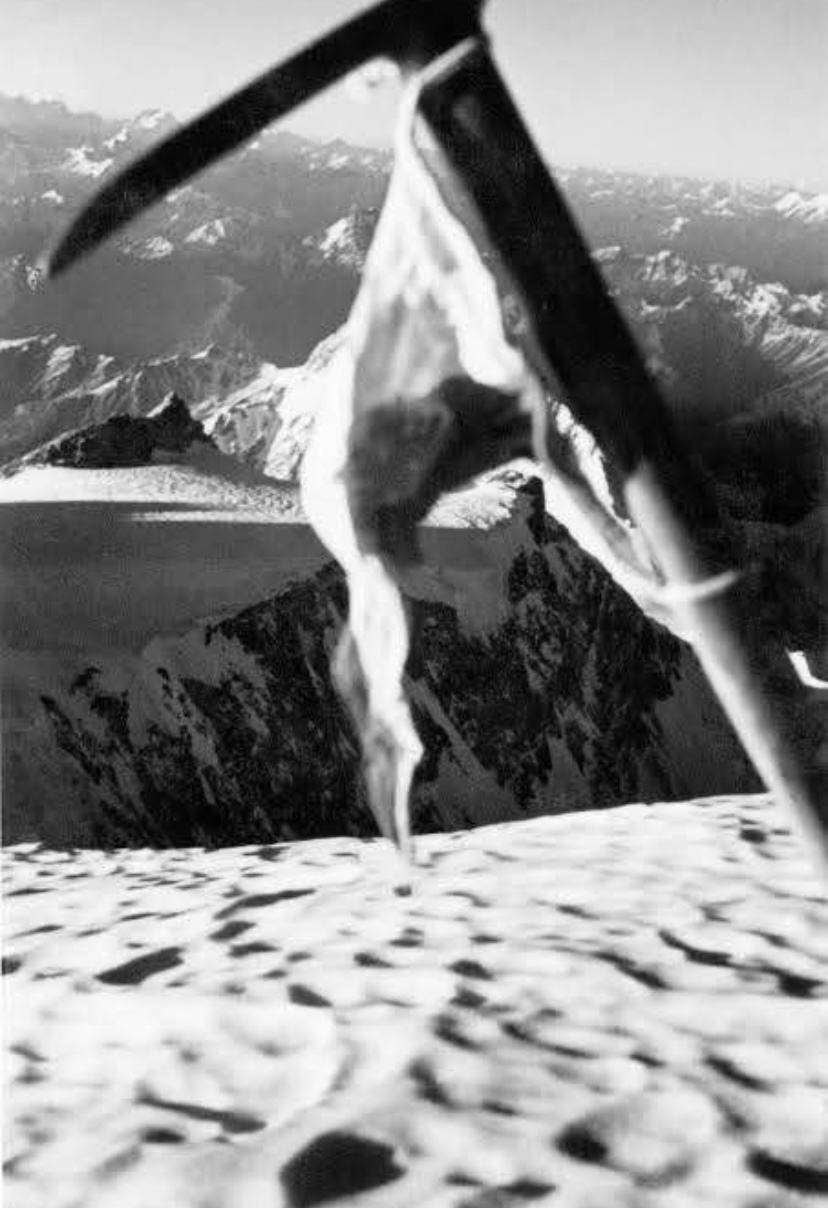

By morning, Buhl reached the Silver Saddle at 7,450m. On July 3, by 2 pm, he hit the Bazhin Gap at 7,830m, dropped his backpack, and climbed the Shoulder (8,070m). After a tough rock section, he reached Nanga Parbat’s summit at 7 pm the same day, after a grueling 17-hour climb. He left his ice axe on the summit.

On the way down, he bivouacked overnight on a narrow ledge at 7,900m. He returned to high camp on July 4 and reached Camp 5 at 7 pm after 41 hours, exhausted and frostbitten.

Buhl's solo push was a monumental achievement and is detailed in his book Nanga Parbat Pilgrimage.

Only four years later, Buhl disappeared on 7,665m Chogolisa.

Later ascents

The second ascent of the Buhl Route came on July 11, 1971, when Slovaks Ivan Fiala and Michael Orolin made the second ascent of Nanga Parbat's Rakhiot Face. Other members of the same expedition achieved first ascents of the southeast peak (7,600m) and the foresummit (7,850m).

The climbers had also attempted the Buhl Route in 1969. That time, adverse weather and logistical challenges halted them before the summit. They reached 6,950m.

This 1971 expedition remains the only successful repetition of the Buhl Route.

The Japanese Route

In the summer of 1995, Japanese climbers Hiroshi Sakai, Yukio Yabe, and Takeshi Akiyama established a new route on the Rakhiot Face, ascending below the East Peak and traversing to the North Ridge near the North Peak.

"After a 1992 reconnaissance to the north and a subsequent study of aerial photos, I was convinced we could climb a new route via the ridge derived from the East Peak of Silver Crag," Sakai wrote in the American Alpine Journal.

The Japanese party consisted of 10 members, though only three members had adequate experience at high altitude. Of these three, two were soon injured and unable to climb.

The expedition began on June 5 with a three-day march from Tatoo to a temporary Base Camp at 3,900m, using 100 porters to carry three tons of supplies. The main Base Camp was at 4,500m on the Great Moraine, higher than typical due to the long summit route. Acclimatization took five days, and they had established Camp 1 at 5,300m on the Rakhiot Glacier by June 11. From here, they deviated from the 1953 route.

The route from Camp 1 to Camp 2 involved a steep wall of snow and granite reaching 5,700m. The climbers faced a grade IV+ rock crack and a hazardous snow gully prone to rockfall named the Confessional Pitch because of its danger. On June 26, a falling stone injured one climber's arm, and he had to withdraw.

"As we climbed higher, we felt more and more rockfall flying down toward us, as our route led toward the upper part of this snow gully," Sakai recalled.

Inching higher, another injury

After overcoming an overhang and a jagged snow ridge, they set Camp 2 at 5,900m on June 25. Above Camp 2, at 6,300m, a 300m ice tower posed a major obstacle. The team navigated a vertical slit in the ice, climbing four pitches at 70°. Beyond this, the route eased into knee-deep snow along a ridge, leading to Camp 3 at 6,700m, established on July 4.

On July 7, Tamura was injured by a falling stone at the Confessional Pitch, requiring a three-day rescue. With only six climbers left, the team abandoned plans to traverse Nanga Parbat and rested until July 12.

The route to Camp 4 traversed the Silver Saddle’s flanks, tackling Yabe’s Crack, a 50m grade V climb. By July 18, after navigating 800m of snow and rock, Camp 4 was set at 7,350m near the Silver Plateau.

The summit push

On July 22, Sakai, Yabe, and Akiyama left high camp toward the summit. However, soon after, they returned to Camp 4 because Akiyama felt pain in his chest, and Yabe’s fingers and toes had gone numb with cold. During that night, they took oxygen to regain their strength.

On July 23, Sakai, Yabe, and Akiyama summited at 5:13 pm via a new route, after a grueling climb through the Silver Plateau and a steep summit wall. They faced exhaustion and worsening weather but reached the top.

The descent was tough, with a bivouac at 7,700m in a snowstorm. The team returned to Camp 4 after 39 hours and reached Base Camp on July 28 amid bad weather. Despite injuries and setbacks, the expedition succeeded, marking a new route on Nanga Parbat’s North Face.

This marked the third successful ascent of the Rakhiot Face and introduced a more direct but equally challenging alternative to the Buhl Route. No further ascents of this route have been recorded.

2008: a new route attempt

In the summer of 2008, Italian climbers Simon Kehrer, Walter Nones, and Karl Unterkircher attempted a new route via the Rakhiot Ice Wall.

The team arrived at Base Camp in late May, spending weeks acclimatizing and observing the Rakhiot Face, noting its avalanche-prone seracs and crevasses. On July 14, they began their summit push at 10 pm, hoping to minimize avalanche risk by climbing at night when it was coldest.

They cached a tent at 4,500m and began climbing again after midnight on July 15, navigating 60° ice and a near-vertical M4/5 mixed wall to 5,700m. After tackling deep snow and a serac, they reached 6,300m by 4 pm, where Unterkircher fell into a crevasse and died. Kehrer and Nones attempted a rescue but found his body buried under snow. Unable to recover it in dangerous conditions, they retrieved his gear and continued up.

Opting against a risky descent, they climbed toward the Silver Plateau via a longer, easier route through avalanche-prone slopes and steep mixed terrain. A storm on July 17 slowed progress with waist-deep snow, forcing bivouacs at 6,650m, 6,800m, 7,000m, and 7,300m.

They reached 7,500m on July 21. On July 22–23, they skied down the Buhl route in poor visibility, surviving two avalanches. Eventually, a Pakistani Army helicopter airlifted them from 5,400m to Base Camp on July 24. Recovering Unterkircher’s body was deemed impossible.

The route, named Via Karl Unterkircher (3,000m, IV-V M4+ 70°-80°), was dedicated to their fallen friend.

Since its last ascent in 1995, the Rakhiot Face remains unclimbed to the summit. Of the 80 people who have died on Nanga Parbat, more than a third perished on the Rakhiot Face.

You can find the climbing history of the Diamir Face here, and the Rupal Face here.

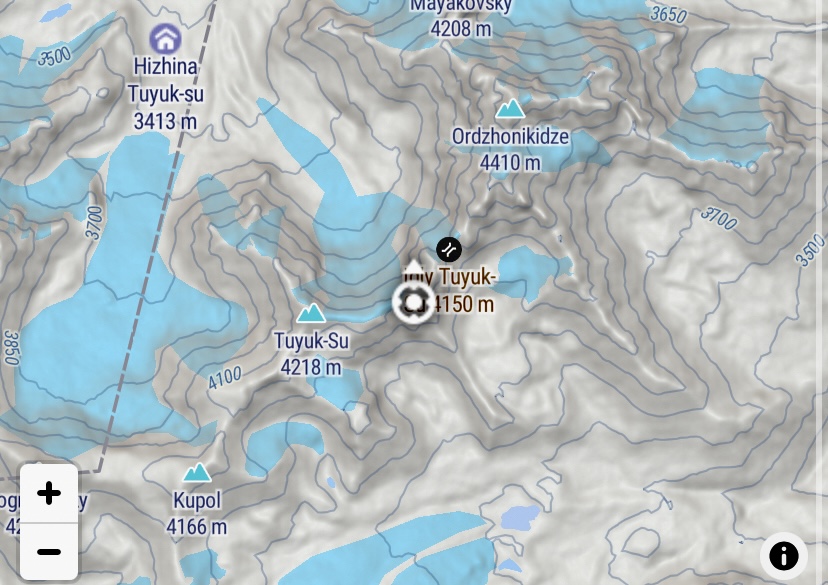

Caro North, Soledad de las Nieves, and Tatin Sanchez likely made the first ski descent of 5,000m Pogranichnik Peak, which is on the border of Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan.

Pogranichnik Peak lies in the Tien Shan mountains of Central Asia, one of the world's great ranges. Pogranichnik means "border guard" in Russian and reflects its location on the Kazakhstan-Kyrgyzstan border. Strong winds, icy slopes, and challenging conditions for both climbing and skiing characterize this remote area.

The team also climbed Uzlovaya Peak, which is about 4,800m high and part of the same Borkoldoy Too subrange.

After summiting Uzlovaya Peak, the team followed a sharp ridge to the top of Pogranichnik.

Due to strong winds, most of the climb had no snow, so they used crampons on the bare ice. But De las Nieves had spotted a potential ski route down Pogranichnik’s north face. Sure enough, they found powder snow between large crevasses and skied down the whole way.

There’s limited information about Pogranichnik Peak’s first climb. In the early 2000s, mountaineers explored the Borkoldoy Too area and summited some unclimbed peaks around 5,000m. Pogranichnik may have been climbed then, but no specific record confirms this.

Caro North is a North Face athlete from Switzerland. Her frequent partner is Soledad de las Nieves of Chile, and Tatin Sanchez is from Argentina.

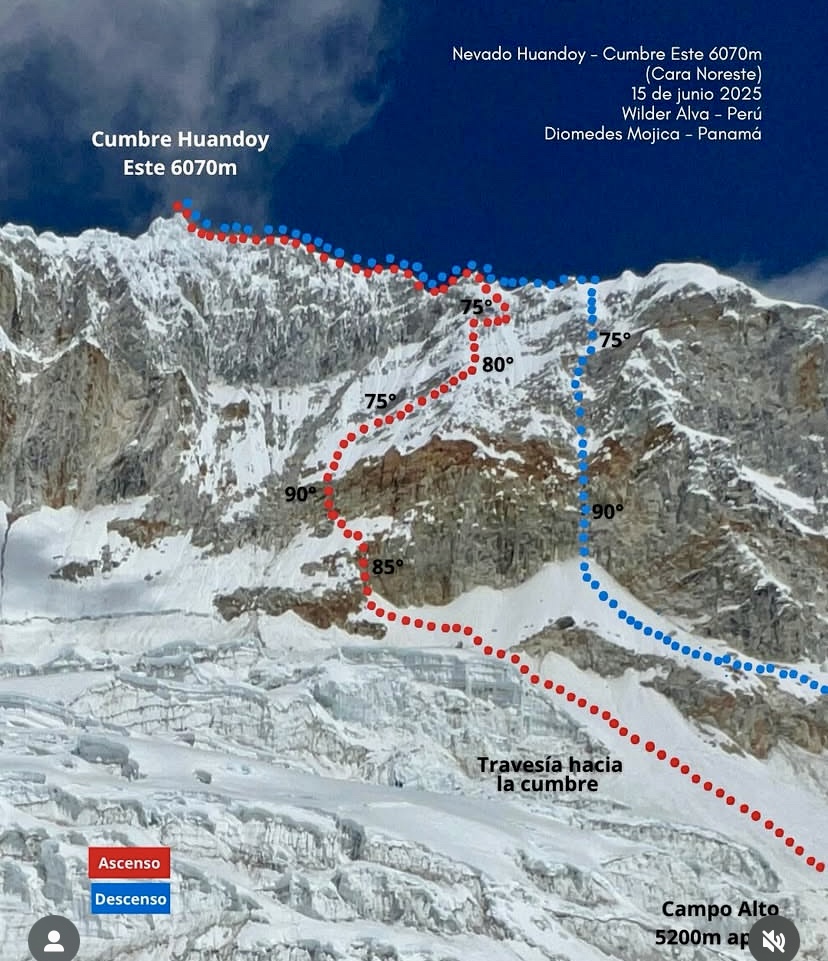

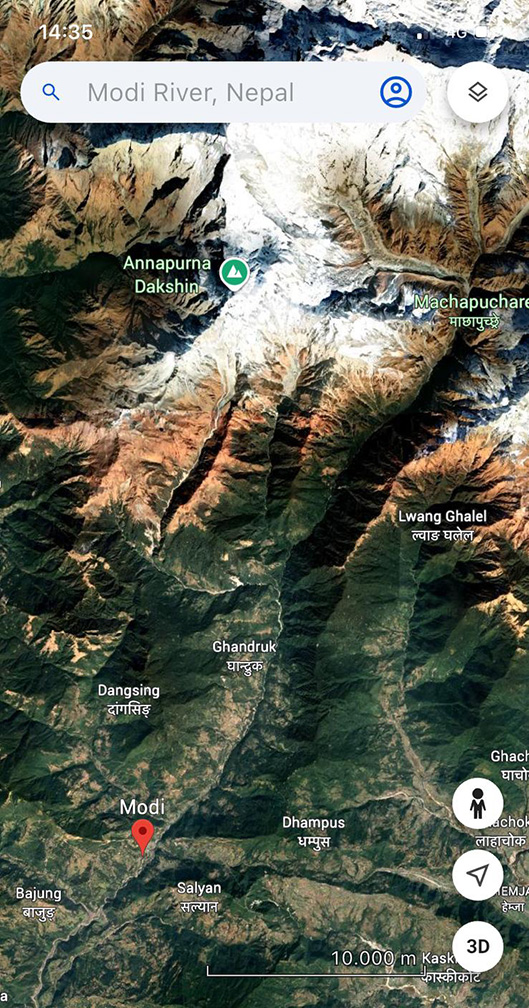

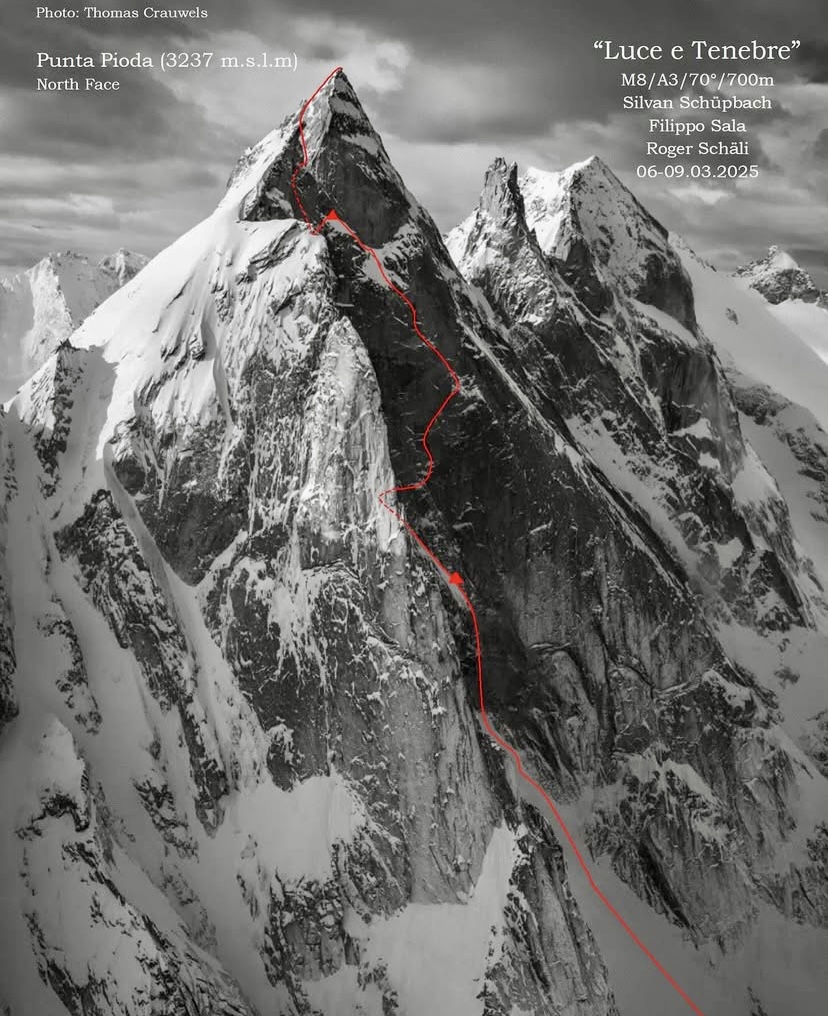

On June 15, two climbers established a difficult new route on the rarely climbed 6,070m Huandoy East in Peru.

Diomedes Mojica of Panama and Wilder Alva Chinchay of Peru climbed via the northeast face and graded their new route 480m, MD+, 75º-90º ice, M4-M5 mixed climbing, UIAA 5+.

The duo climbed in alpine style over 18 hours (11 hours up, and seven hours down).

Huandoy East is highly technical, steep, and dangerous, and even experienced climbers almost never attempt it. This is the first ascent of Huandoy East by a Panamanian and marks Chinchay as the first person to summit all four Huandoy peaks (North, South, East, and West).

World's highest tropical range

Huandoy lies in Peru's Cordillera Blanca, the world's highest tropical mountain range. Its highest peak, Huandoy North, reaches 6,395m and is the second-highest in the range after 6,757m Huascaran. The Huandoy massif lies near the Llanganuco Valley and its lakes, with views of other big peaks like Huascaran and Chopicalqui.

Huandoy is a tough climb due to its steep ice, glaciers, and complex ridges. It's popular with experienced mountaineers who use their ice-climbing and high-altitude skills.

Huandoy, also called Tullparaju in Quechua, may come from local words meaning snowy fireplace.

Erwin Schneider and Erwin Hein from the German Alpine Club first ascended Huandoy North via its south side on Sept. 12, 1932.

Diomedes Mojica, 31, is a student at Centro de Estudios de Alta Montana and an aspiring UIAGM mountain guide. On June 3, one week before Huandoy East, he summited Huascaran via a new route. His recent climb of Huandoy East establishes a new milestone for Panamanian mountaineering.

Wilder Alva Chinchay is also training as a UIAGM mountain guide. He is experienced on the Cordillera Blanca's high-altitude technical routes.

The ninth-largest mountain in the world, Pakistan's 8,125m Nanga Parbat has three main faces: the south-facing Rupal Face, the northeast-facing Rakhiot Face, and the northwest-facing Diamir Face.

On June 24, David Goettler, Tiphaine Duperier, and Boris Langenstein summited via the Schell Route after an 18-hour, alpine-style push from Camp 3 at 6,800m. From the summit, Duperier and Langenstein made the mountain's first complete ski descent, including the entire Rupal Face, according to Montagnes Magazine. Goettler paraglided from 7,700m to Base Camp.

This article will explore the climbing history of the Rupal Face.

The tallest mountain face

Many consider Nanga Parbat’s 4,600m Rupal Face the world's tallest mountain face because it forms a continuous, steep wall from the Rupal Valley at 3,500m to the summit at 8,125m. Its steep icefields, rocky buttresses, avalanche-prone slopes, and brutal weather make it a formidable challenge.

By contrast, 7,782m Namcha Barwa’s south face (5,282m to 5,782m high) and 7,294m Gyala Peri’s south face (4,794m to 5,294m high) both have greater total relief but include gentler, less consistent slopes, reducing their status as unbroken climbing faces.

The Rupal Face has had just 12 successful ascents across four routes.

The Messner Route: The first ascent

In 1970, Reinhold Messner and his brother Gunther climbed Nanga Parbat via the Rupal Face. They climbed up the South-Southeast Spur (often referred to as the Messner Route). The expedition was led by Karl Maria Herrligkoffer, and the Messner brothers reached the summit on June 27.

Because of worsening weather, exhaustion, and Gunther’s altitude sickness, the Messner brothers were unable to descend the Rupal Face. Instead, they made the first traverse of Nanga Parbat by descending the Diamir Face, following a route along the Mummery Rib’s lower slopes and improvising a westward path toward the Mazeno Ridge’s lower slopes, crossing gullies and snowfields near the Diamir Glacier.

Tragically, Gunther Messner died during this descent, likely in an avalanche on the Diamir Face.

Messner's route repeated

In 2005, a South Korean team started from Base Camp on April 20 in heavy snow. They set up Camp 1 at 5,280m and Camp 2 at 6,090m along the 1970 Messner Route.

They were still on the mountain in early June when bad weather hit them hard and destroyed their tents. Despite this, they made Camp 3 at 6,850m before an injury stopped their first summit attempt.

On July 13, Kim Chang-ho and Lee Hyun-jo left Camp 4 at 7,125m. After 24 hours, dodging falling rock and ice, they summited late on July 14. The climbers went down the Diamir Face, survived an avalanche, and reached Base Camp after 68 hours. On the summit, they found a container left by Reinhold Messner and returned it to him as proof of their climb.

An alpine-style attempt on the Messner Route

A notable attempt of the 1970 Messner Route came in 1988. Canadians Kevin Doyle, Ward Robinson, and Barry Blanchard, plus American Marc Twight, prepared by climbing nearby peaks.

Doyle, Robinson, and Blanchard tackled a new route on 6,500m Shigeri’s north face, spending two unplanned nights at altitude. Twight soloed a new route on Laila’s south face and east ridge (6,000m). The three of them reached 7,000m on the easier Schell Route.

On July 9, the team started on the Rupal Face by the Messner Route. They left with light gear: five days’ food, eight days’ fuel, two ropes, and some climbing equipment.

The first 1,000m were easy, but after camping below Wieland Rocks, the terrain got steep and hard, needing two ice tools. At 6,400m, they avoided a rockfall-prone gully, climbing tough mixed ground. In two and a half days, they gained 3,170m, resting for half a day on July 12.

They climbed a steep ice barrier and struggled through deep snow. At 7,300m, they faced hard, brittle ice in the Merkl Gully. By July 13, they reached 7,700m, close to the summit.

A close call

Here, their luck ran out. A sudden storm hit, with lightning, 160kmph winds, and avalanches. Robinson, sick and hypothermic, could barely move. An avalanche nearly swept them off the mountain while rappeling, but their one ice screw held. After five hours, they reached the Merkl Icefield and found shelter for Robinson.

Twight and Blanchard descended to 7,000m, losing a tent and both ropes. At 6,700m, they found a discarded pack from the 1984 Japanese team with ropes and gear. Their find helped them escape the mountain over the next day and a half.

"The atmosphere quivered, and I could hear the tension of the storm's electrical charge -- white noise crackling in my ears," Blanchard wrote in his book The Calling. "The midday sky was as dark as dusk...The avalanche had ended 27 minutes after it had begun. Ward's face looked old. Deep lines dragged down the corners of his mouth; I had never seen those lines in his face before. His eyes had the improperly focused look of shock, with too much black in his pupils."

On July 25, they tried again, climbing to 7,300m in just over two days. Sick again, Robinson retreated from 7,000m. Soon after, clouds and a brewing storm stopped the rest of the team, and they descended in 13 hours.

Importance of the 1988 attempt

This expedition was significant for several reasons. First, it highlighted the extreme challenge of the Messner Route, reinforcing its reputation as one of mountaineering’s toughest objectives. No team had summited via this route since 1970, and the 1988 attempt underscored why: the combination of technical ice climbing, unpredictable weather, and constant rockfall and avalanche risks demands exceptional skill and luck.

The team’s alpine-style approach — carrying minimal gear to move quickly — tested the limits of the strategy, showing both its potential and its vulnerabilities when equipment was lost. Their survival, especially after the storm and Robinson’s altitude sickness, demonstrated remarkable resilience and decision-making under pressure. Finding the Japanese pack was a stroke of luck that likely saved their lives.

Though they didn’t reach the summit, their 7,700m high point and detailed account provided valuable insights into this formidable route.

The Schell Route

The Schell Route has eight successful ascents.

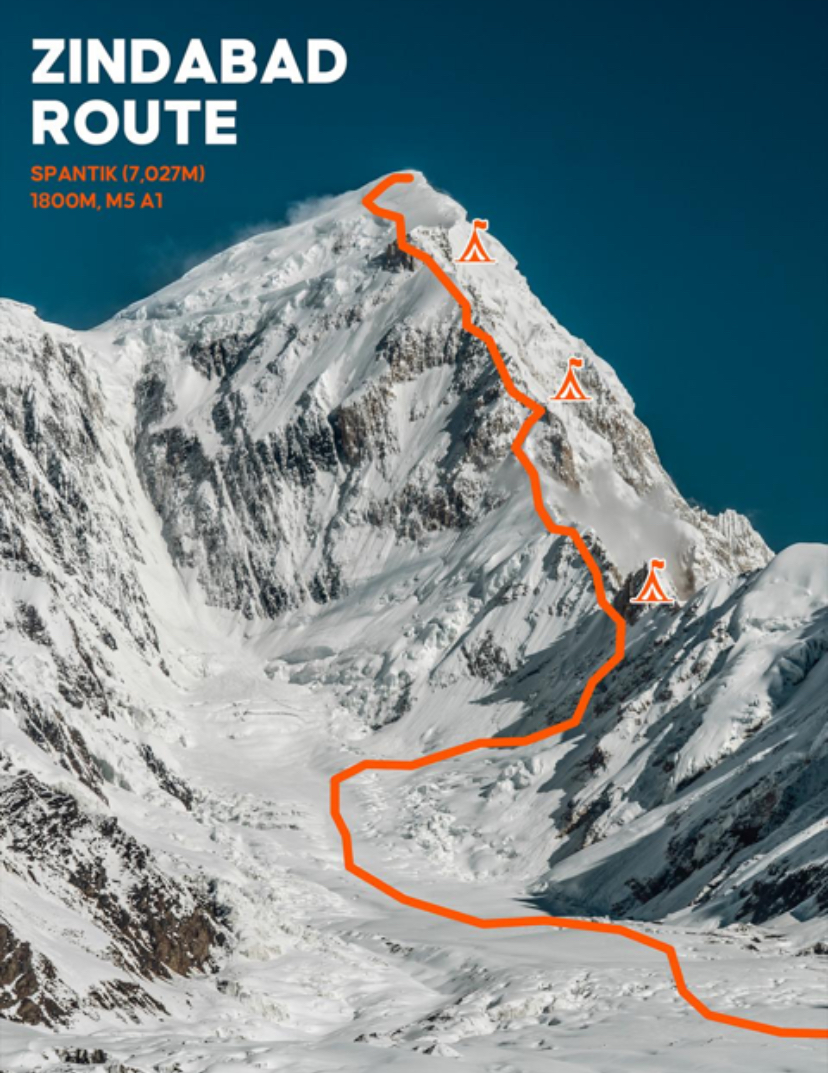

We previously detailed the first ascent of the Schell Route, climbed in 1976 by Austrians Hanns Schell, Robert Schauer, Siegfried Gimpel, and Hilmar Sturm. David Goettler, Tiphaine Duperier, and Boris Langenstein repeated this long, difficult route a few days ago.

With only eight successful climbs, the importance of this latest ascent is obvious. The other ascents are: 1981 by Ronald Naar; 1984 by Oscar Cadiach and Jordi Magrina; 1990 by Marija Frantar and Joze Rozman; 1990 by Reinmar Joswig and Peter Mezger; 1990 by Osamu Nakajima; 2013 by Zsolt Torok, Teofil Vlad Dima, Aurel Salasan, and Marius Gane.

The 2025 ascent via the Schell Route comes 12 years since its last ascent in 2013, and Duperier becomes just the second woman to achieve this remarkable feat. Goettler had attempted this route four times previously.

The Southeast Pillar: The Polish-Mexican Route

In 1982, Swiss climber Ueli Buhler nearly conquered the Southeast Pillar. He reached the 8,042m south summit but was unable to continue to the main peak.

In 1985, a Polish-Mexican expedition opened a new route on the Rupal Face by the Southeast Pillar.

This 1985 expedition, led by Pawel Mularz, tackled the dangerous pillar in brutal weather. During the climb, Andrzej Samolewicz survived a 600m fall with only minor injuries, but an avalanche killed Piotr Kalmus while he descended from Camp 2 to Camp 1. On July 13, Jerzy Kukuczka, Zygmunt Andrzej Heinrich, Carlos Carsolio, and Slavomir Lobodzinski reached the summit from Camp 5, marking Kukuczka’s ninth 8,000m peak.

A winter solo attempt ends in tragedy

In the winter of 2012-13, Joel Wischnewski, a little-known mountaineer from France, attempted a highly ambitious solo climb of the Southeast Pillar on Nanga Parbat’s Rupal Face.

He left France at the end of December 2012, reached base camp on January 9, 2013, and made his last journal entry on February 6 from Camp 2, indicating he was moving up the Southeast Pillar.

When he didn't return, his agent in Pakistan launched a search. Three experienced Pakistani mountaineers climbed up the lower part of his proposed route, but found no trace of the Frenchman.

Wischnewski's body was found on Oct. 10, 2013, at approximately 6,100m on the Rupal Face near the foot of an icefall. Local villagers spotted his boots after the summer snowmelt in early September and notified the French embassy.

A team led by Brigadier Akram Khan recovered the body, and it was buried at the Herrligkoffer climbers’ cemetery near Base Camp. Wischnewski likely died in an avalanche.

The Central Pillar: The Anderson-House Route

Vince Anderson and Steve House climbed the Rupal Face by a 4,100m new route (M5, 5.9, WI4) in the autumn of 2005.

The duo's route up the Central Pillar was alpine-style and faced tough challenges, like loose rock on a hard 5.9 section. On day three, they reached a hanging glacier, then followed an icy ramp to their last camp at 7,400m. There, they joined the Messner Route at 7,900m and summited on September 6. Anderson and House descended by the Messner Route.

The 2005 Central Pillar route, distinct from the 1970 Messner Route and the 1985 Southeast Pillar, was a significant achievement and earned them the 2006 Piolet d’Or. Their climb followed a 2004 attempt by House and Bruce Miller, which reached 7,500m but was halted by altitude sickness.

A central route attempt

In 2005, Slovenian Tomaz Humar attempted a challenging new central route up the Rupal Face. He had previously tried a similar route in 2003 but retreated because of poor weather and health issues.

On this second attempt, Humar reached about 6,300m before bad weather trapped him, forcing him to dig into the snowy slope and wait for clearer skies and fewer avalanches. However, after days of waiting, he required a risky helicopter rescue by Pakistani pilots.

Climbing journalists and peers criticized him, but Slovenians watched the drama unfold on TV and celebrated Humar's safe return as a national hero. Four years later, Humar died on Langtang Lirung.

Another new route attempt

In 2018, Czech climbers Marek Holecek and Tomas Petrecek attempted a new alpine-style route on the Rupal Face.

Initially, they planned to establish a new line to the right of the 2005 Anderson-House route on the Central Pillar. However, bad weather and heavy snowfall forced them to adjust their plans. When a weather window opened, they shifted to a line closer to the 1970 Messner Route, following it until the Merkl Rinne, a steep gully used by the Messner brothers. From there, they deviated, climbing a new variation through rocky buttresses to the left of the gully, seeking a natural line of weaknesses.

After six days on the face, they reached approximately 7,800m on September 2. There, they were forced to retreat in increasingly strong winds (up to 100kmph). They were about 300m below the summit when they turned back.

They descended the Rupal Face, which Holecek described as extremely challenging, comparing it to a "cabriolet [horse-drawn carriage] trip without a windscreen in an ice storm."

Winter attempts

Since 1988, nine winter attempts have targeted the Rupal Face, but all were defeated by the extreme conditions.

Maciej Berbeka of Poland led three attempts. In 1988-89, his team reached 6,500–6,800m on the Messner Route before switching faces in harsh weather. In 1990-91, a Polish-English team reached 6,600m on the Schell Route, and in 1991-92, they reached 7,000m. Both times, severe weather stopped them.

Krzysztof Wielicki’s 2006-07 Polish expedition reached 6,800m on the Schell Route but retreated in fierce winds. As we previously noted, Joel Wischnewski vanished during his winter solo attempt in 2013. Tomasz Mackiewicz’s winter attempts on the Schell Route included a 2012-13 solo climb to 7,400m, and a joint effort with David Goettler to 7,200m in 2013-14.

In the winter of 2014-15, Russians Nikolay Totmjanin, Sergei Kondrashkin, Valery Shamalo, and Victor Koval reached 7,150m on the Schell Route before deteriorating weather, including high winds, snow blizzards, and zero visibility, forced them back.

Cleo Weidlich (a Brazilian-born American climber) and her Sherpa team abandoned their 2015-16 Schell Route attempt in treacherous conditions.

In 2021-22, Herve Barmasse and David Goettler stopped at 5,670m on the Schell Route because of avalanche risk and bad weather.

The Schell Route remains unclimbed in winter

While Nanga Parbat was finally climbed in winter -- on Feb. 26, 2016, via the Kinshofer Route on the Diamir Face by Simone Moro (Italy), Alex Txikon (Spain), and Ali Sadpara (Pakistan) -- the ever-formidable Rupal Face remains unclimbed during the harshest season.

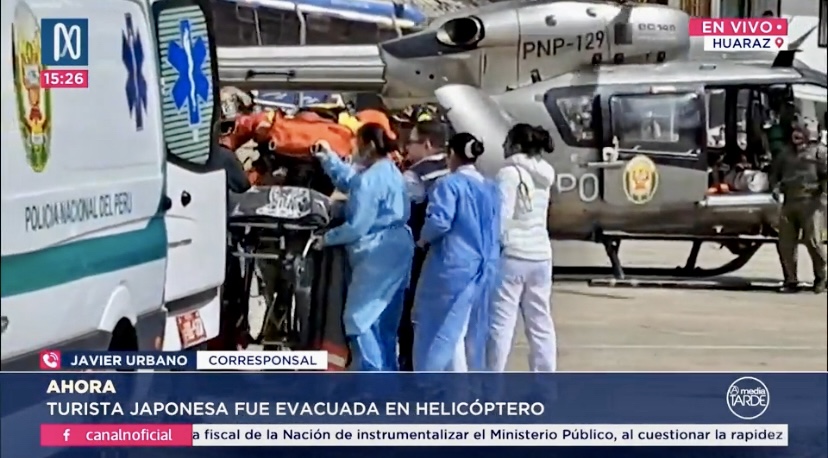

Experienced climbers Saki Terada and Chiaki Inada from Japan faced severe challenges while climbing 6,757m Nevado Huascaran earlier this week. Their climb of Peru's highest peak ended in tragedy.

The duo became stuck at 6,600m during their descent. Inada died, and rescue teams struggled to help Terada down.

Yesterday, rescuers finally evacuated Terada from the mountain, transporting her to Víctor Ramos Guardia Hospital in Huaraz. She is in a critical but stable condition, suffering from severe dehydration and frostbite on her hands and feet from prolonged exposure to extreme cold, according to Infobae.

Today, medics will transfer her to a hospital in Lima, Peru's capital city, where she can continue treatment.

Inada's body recovery underway

Efforts are underway to recover Inada's body. Inada, a 40-year-old doctor for Wilderness Medical Associates Japan (WMA), succumbed to hypothermia and cerebral edema.

According to some Peruvian sources, rescue services found the climbers at approximately 6,500m on the south face of Huascaran’s south peak, just below the summit. They were on the technical Escudo route, a 600m ice and snow wall known for its steep terrain and harsh weather.

Terada and Inada had arrived in Peru two weeks ago and had at least one acclimatization hike before starting the ascent on Huascaran. Presumably, the two women summited on June 23, and the problems started on June 24 when they encountered foggy weather and low visibility.

Timeline of events

Today, WMA Japan has published a report on what happened. Below we have translated it into English with minor edits to improve clarity. Note all times referred to are Peru Standard Time.

June 24

At around 1:30 am:

- Chiaki Inada became incapacitated due to suspected hypothermia. A distress signal was sent via Garmin’s SOS satellite device to a private rescue agency in Peru. The agency contacted WMA Japan to verify the situation.

At around 4:00 am:

- A response headquarters was established, and negotiations began with various parties.

- Requests for rescue to the local private rescue agency and to local police authorities.

- Request for support through the Japanese Embassy in Peru.

At around 7:30 am:

- Online meeting with Japanese and Peruvian stakeholders.

- Survival of Inada and Terada confirmed.

- Text communication with Japan was possible until around 10:00 am. The climbers were stranded and incapacitated at the site.

- Rescue arrangements confirmed.

- The climbers' problems occurred around 6,600m, just below the summit. No helicopters in Peru can fly at this altitude, so the rescue team had to fly to the Huascaran refuge hut, then proceed on foot to the site. The plan was to bring both climbers to the refuge hut by land, followed by a helicopter rescue.

- Cooperation from local police was secured through the Japanese Embassy in Peru.

At around 4:00 pm:

- A joint rescue operation by local police and private teams began. Nine team members, split into three groups, arrived at the Huascaran refuge hut.

- The team began climbing toward the stranded climbers on foot.

- Additional teams were dispatched through efforts by the Japanese Embassy and local stakeholders.

- The rescue team consisted of over 10 members, primarily local mountain guides, operating in several groups.

June 25

At around 7:30 am:

- Staff at a lodge at the mountain’s base reported phone contact with Inada and Terada

- Though their responses were not entirely clear, their voices were confirmed.

At around 12:00 pm:

The rescue team approached the SOS location but encountered difficulties due to large crevasses. They continued searching for a viable route.

At around 3:00 pm:

- The rescue team reached the two stranded climbers. Terada was conscious. Inada was unconscious and in critical condition.

- The team provided first aid and considered transport options through the night.

At around 6:00 pm:

- Deteriorating weather conditions made rescue operations extremely difficult, rendering simultaneous transport of both climbers impossible.

- Local rescue teams and authorities determined Inada’s death at the site.

- Further rescue activities became unsafe, so Inada’s body was temporarily left at the site with its location recorded via GPS.

- The rescue team focused on evacuating Terada.

June 26

At around 9:00 am:

- Terada was walking at approximately 5,100m (the pickup point is at about 4,500m).

- A helicopter and local medical personnel were on standby for transport.

- The plan was to transport Terada to a hospital at the base via helicopter upon reaching the pickup point.

At around 1:45 pm:

- Terada safely reached the helicopter pickup point at the refuge hut.

- Partway down, she became unable to walk independently and was carried by the rescue team, but remained fully conscious.

- Final landing arrangements and flight permissions were being coordinated, with the helicopter set to deploy once conditions were met.

At around 2:30 pm:

- Thanks to the rescue team’s swift coordination, Terada was safely admitted to a hospital.

- Preparations for the recovery of Inada’s body have begun.

At around 10:00 pm:

- A team of local mountain police and guides left to retrieve Inada’s body.

On June 23, two female Japanese mountaineers, Saki Terada, 36, and Chiaki Inada, 40, became stranded on 6,757m Nevado Huascaran, Peru’s highest peak. One of them is now confirmed dead.

The two veteran climbers arrived in Peru in early June and spent two weeks acclimatizing. They then started climbing Huascaran and likely summited earlier this week.

The weather has been challenging on Huascaran, with poor visibility above 6,000m. Terada and Inada became lost in the fog in the huge area just below the summit. They could not find their high camp and had to bivouac at around 6,500m, according to Latina Noticias.

There, health problems set in. One of the climbers went snowblind because of cerebral edema, and in nighttime temperatures as low as -30°C, hypothermia also affected them. Inada was in particularly poor condition.

Distress call

Terada and Inada sent a distress call via their InReach device on June 24, after spending two nights outside. Deep snow and poor visibility continued to complicate the situation. The climbers had cell service on the mountain and also asked for local rescue.

Peru’s National Police mobilized specialized rescue teams. A helicopter made three rescue sorties, but continuing poor weather didn't allow it to reach the two climbers. So from an altitude of 4,800m, rescuers started to move up on foot toward them, according to the TV station, Latina Noticias.

On June 25, both climbers were located, thanks to their InReach device. Unfortunately, by then, Inada had succumbed to hypothermia and was confirmed dead at the scene. Rescuers are currently bringing Terada down the mountain.

Terada and Inada are experienced mountaineers, and Inada also served as an expedition doctor.

Terada was a member of the Himalayan Camp, a Japanese mountaineering group known for organizing high-altitude expeditions. In 2023, she participated in the Sharpu VI expedition in Nepal.

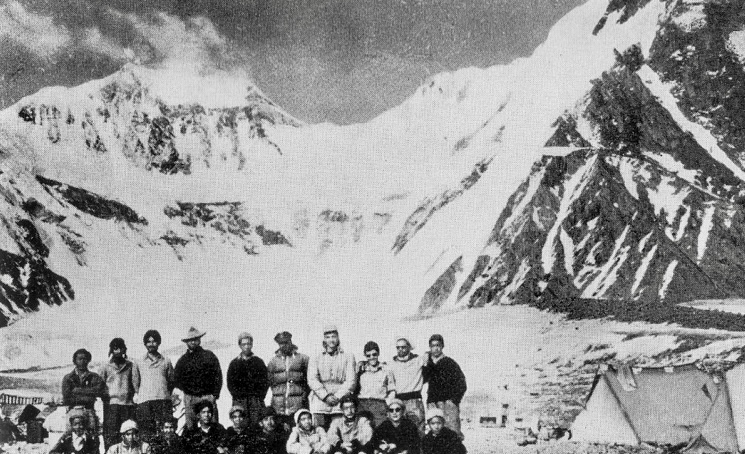

Captain Manmohan Singh Kohli, a pioneering Indian mountaineer, passed away on June 23 at the age of 93.

Celebrated for leading India’s first successful Everest expedition in 1965, Captain M.S. Kohli's career also included an Antarctic expedition and many other Himalayan ventures. His work as a mountaineer, author, editor, Himalayan Club president, and Indian Mountaineering Foundation president shaped Indian mountaineering.

Born December 11, 1930, in Haripur (now Pakistan), Kohli joined the Indian Navy in 1950, rising to the rank of Commander. He trained in the UK and developed leadership skills. By 1956, he began Himalayan mountaineering.

Kohli took part in over 20 adventures in the Greater Ranges. In 1956, he climbed 7,672m Saser Kangri in the Karakoram. In 1959, with K.P. Sharma, he topped out on 6,861m Nanda Kot in the Kumaon Himalaya. It was just the second ascent of the mountain.

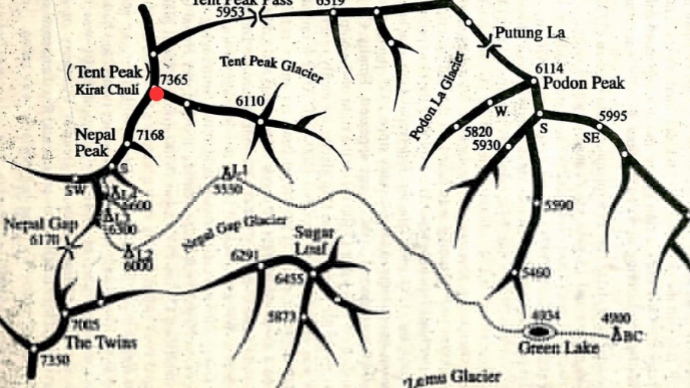

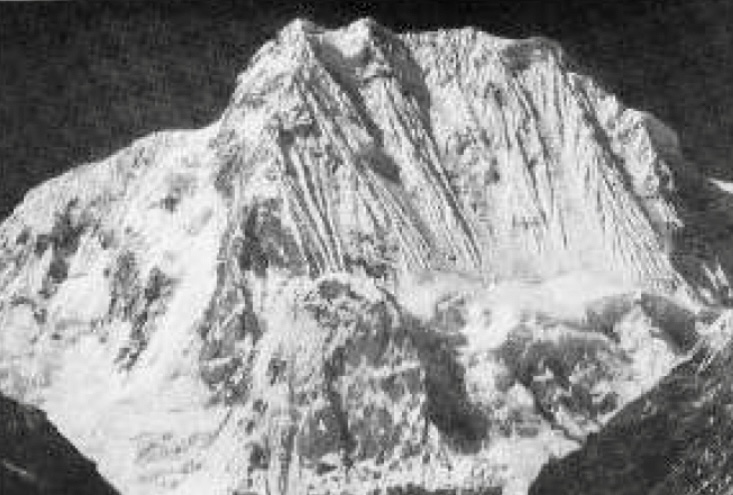

Between 1961 and 1964, Kohli led three successful expeditions -- the first ascent of Annapurna III, a climb of 7,816m Nanda Devi, and an expedition to 7,198m Nepal Peak.

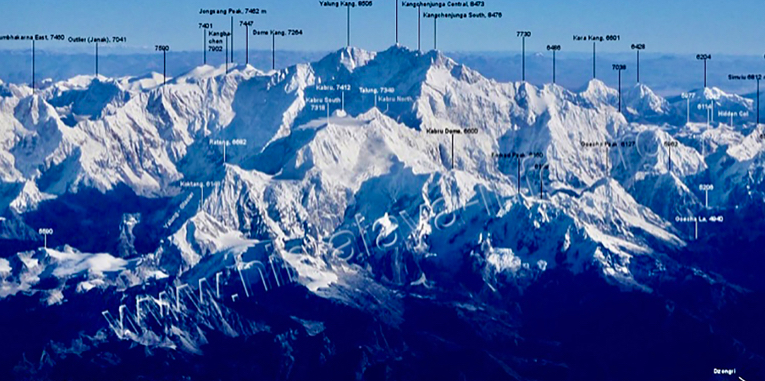

In the 1960s, Kohli led and summited Kabru Dome and Rathong, strengthening India’s eastern Himalayan presence. In 1965, Kohli led a covert Indian-American mission to place a nuclear-powered device to monitor Chinese tests but did not summit due to harsh conditions.

Everest expedition leader

In 1965, Kohli led the first successful Indian expedition to Everest. Nine climbers on his team summited between May 20–29. It set a record for the most summiters on one expedition, which remained unbroken for 17 years.

His leadership on that expedition was extraordinary. Indira Gandhi, who later became the Prime Minister of India, said of Kohli at the time: "Commander Kohli’s expedition...was a masterpiece of planning, organization, teamwork, individual effort, and leadership.”

Later, Kohli climbed several European peaks with Tenzing Norgay. In 1982–1983, he led India’s first civilian Antarctic expedition, supporting scientific exploration.

He was also a committed alpinist beyond expeditions. As president and vice president of the Himalayan Club (1980–1983), Kohli edited the Himalayan Journal. As president of the Indian Mountaineering Foundation (1989–1993), he promoted adventure and youth engagement. In 1989, he co-founded the Himalayan Environment Trust with Sir Edmund Hillary. It was supported by Maurice Herzog, Reinhold Messner, Junko Tabei, and Chris Bonington.

Kohli was much loved and respected in international mountaineering circles. He promoted mountaineering and trekking through many presentations around the world.

Kohli authored Nine Atop Everest, Spies in the Himalayas (with Kenneth Conboy), The Great Himalayan Climb, and A Life Full of Adventures, among several other publications.

Kohli received the Padma Bhushan (1965), Arjuna Award (1965), Ati Vishisht Seva Medal (AVSM), and Tenzing Norgay Lifetime Achievement Award. He lectured at the Alpine Club (UK) and the American Alpine Club.