While most people love a good animal story, scientists believe there's more going on than just the proliferation of smartphones with built-in cameras.

The ice caps which cover our planet's poles are key to understanding global weather patterns and changing climate. But we still don't have a complete understanding of how they work, and what goes on beneath the frozen surface.

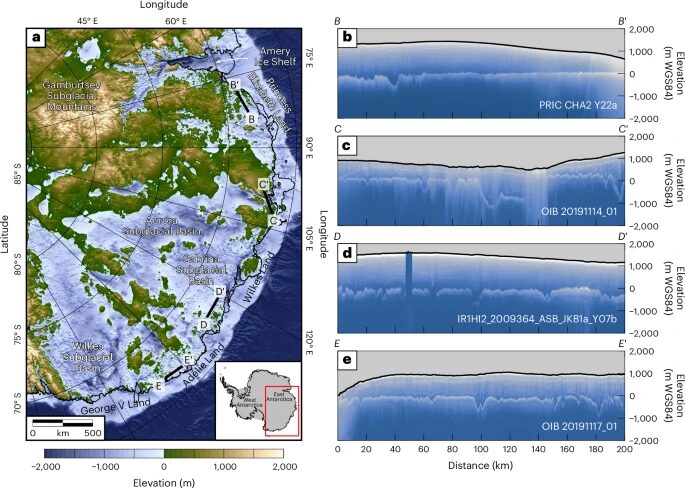

A group led by researchers at the UK's University of Durham used radar to glimpse beneath the coast of East Antarctica. In a new study, they announced their findings: Ancient riverbeds beneath Antarctica control the behavior of the ice sheet above them.

Reconstructing ancient landscapes

It is crucial to understand how much, and how quickly, the East Antarctic Ice Sheet is going to melt as temperatures continue to rise. It's the largest of Antarctica's three ice sheets, and it contains enough water to raise the sea level by over 50 meters.

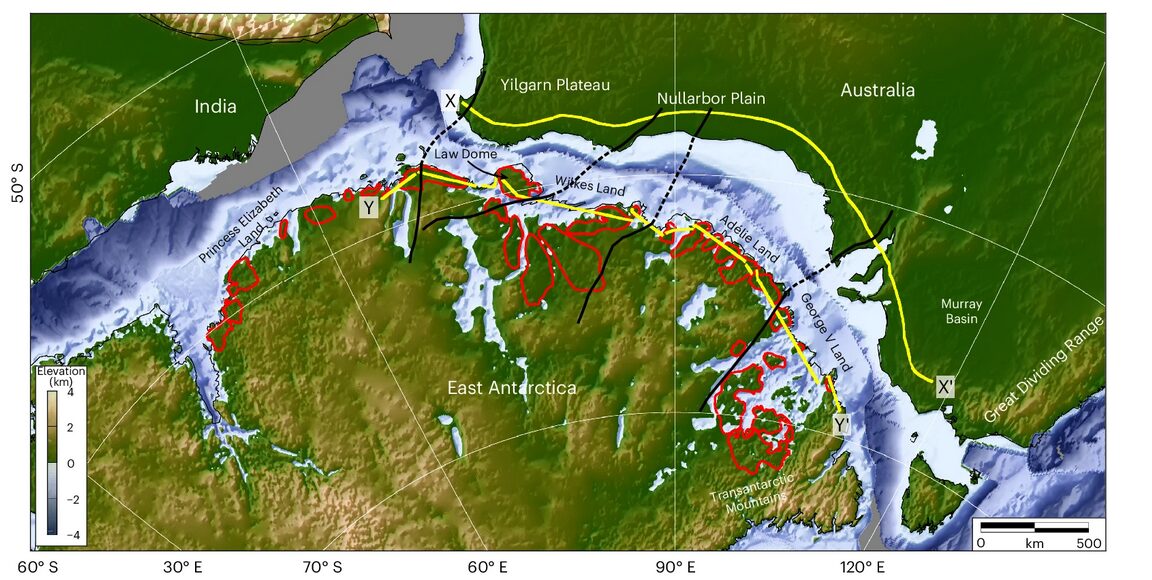

The behavior of an ice sheet depends on more than just surface conditions. The landmass hidden beneath the ice impacts how quickly it melts and where it collapses. To get an idea of what that hidden landscape looks like, researchers analyzed a series of radar scans covering 3,500km of East Antarctica.

The scans found what was once a coastal plain formed by fluvial erosion. Between 80 million years ago, when Antarctica divorced Australia, and 34 million years ago when it became covered in ice, rivers flowed across East Antarctica and into the sea. Those rivers carved out a smooth, flat floodplain all along the coast. Breaking up the plain are deep narrow troughs in the rock. These plains covered about 40% of the area they scanned.

This find confirms previous, fragmentary evidence for a very flat, even plain beneath the icy expanse.

Hopeful findings

This is good news for those of us who enjoy not being underwater. Computer programs modeling future climate behavior now have more data to work on. Before, as the study's lead author, Dr. Guy Paxton, said in a Durham press release, "The landscape hidden beneath the East Antarctic Ice Sheet is one of the most mysterious not just on Earth, but on any terrestrial planet in the solar system."

Understanding the terrain beneath the ice makes it much easier to understand how and where the ice will move. “This in turn will help make it easier to predict how the East Antarctic Ice Sheet could affect sea levels.”

More than that, however, the ancient fluvial plains may be slowing down the melt. The study suggests that the flat plains may be acting as barriers to ice flow. Fast-moving glaciers pass through the deep channels, but the bulk of the ice, atop the plains, is moving much more slowly.

Ultimately (as they always do), researchers stressed the need for more investigation. Further studies would involve drilling all the way through the ice and taking samples of the rock below. So look forward to that.

Last month, a large rockfall swept down the south face of the Aiguille du Midi in the Mont Blanc massif of the French Alps. It has now been estimated that approximately 523 cubic meters broke away, the equivalent of 15 shipping containers of rock.

The scar from the missing rock is clearly visible, and a pile of fresh debris now sits at the base. In the days before and since the fall, climbers have reported cracking sounds and traces of runoff on the south face, suggesting that the recent slide won't be the last.

On July 3, one user on the UK Climbing forum wrote, “Several teams have reported signs of an impending collapse: unusual noises (creaking, cracking, etc.), vibrations coming from the wall, and the sound of water flowing without any visible water in the Kohlmann/Clair de Lune area (extreme right hand side) of the south face of the Aiguille du Midi. A 12-meter block fell down a few weeks ago. Probably best to avoid in this hot weather!”

The 1st june rockfall at Aiguille du Midi south face was 523 m3!

Cracking noises and runoff traces above the scar (small red circle) indicate thawing permafrost and that the upper slab could fall as well!

Be careful when passing through this area!

Data/analysis: Xavier Cailhol

— Melaine Le Roy (@subfossilguy.bsky.social) 9 July 2025 at 13:24

Classic climbing area under threat

The Aiguille du Midi (3,842m) is a popular climbing area. Its south face features classic granite routes such as the Rebuffat–Baquet and the Contamine. These climbs are close to the top of the Aiguille cable car and popular early in the summer.

But in recent years, the face has become much less predictable. Warmer summers have melted the permafrost that once glued the mountain together, leading to a steady but unpredictable increase in rockfall.

Since the early 2010s, climbers and guides have reported more severe rockfalls across the Alps. To name just a few: In 2018, a huge chunk of rock from the south face of the Trident du Tacul near the Grand Capucin came crashing down. In 2023, large rockfalls took place on the Aiguille du Midi and Mount Pelvoux. Then in 2024, part of the west face of the Dru, below the Bonatti Pillar, fell.

Rock avalanche deposit from 1st June below Aiguille du Midi south face!

Xavier Cailhol (05 July) and Philippe Batoux (1st June)

Look how much snow disappeared in June!pic.twitter.com/z6yfp2G4rE

— Melaine Le Roy (@subfossilguy) July 5, 2025

Some of these events have destroyed climbing routes entirely or forced the establishment of new lines. The Aiguille du Midi itself has seen smaller rockfalls almost every year, but the June 2025 collapse is one of the largest.

As the Alps continue to warm, events like this are becoming part of the landscape. For climbers and visitors, it’s a reminder of how fragile the high alpine environment is.

The National Science Foundation (NSF) is an independent agency funds scientific and technological development across the United States and its territories. It also funds research and maintains facilities in Antarctica.

Well, it did do that, anyway. The Trump administration's cuts have slowed operations in Antarctica to a crawl. Scientists warn that climate research conducted there is vitally urgent. Despite this, the NSF is preparing for an operational retreat from Antarctica.

End of U.S. Antarctic dominance

For decades, the United States has been one of the most prominent forces on the southernmost continent. With three large Antarctic bases, a network of research vessels, and the South Pole Highway, which runs across the Ross Ice Shelf, the United States maintains a significant amount of Antarctic infrastructure.

However, that infrastructure has been in decline, especially in the wake of COVID-19. Last summer, the 30-year charter on the Antarctic Research Support Vessel Laurence M. Gould expired. Citing budgetary constraints, the NSF did not renew the charter, leaving only one functioning vessel.

The aging Antarctic stations also experienced cuts. Trump recently canceled the construction budget for the McMurdo Sound base. McMurdo Station has been in operation since 1956. From its position on Ross Island, it acts as a logistical and transport hub for the rest of Antarctica. However, its facilities are desperately in need of repairs and upgrades. Last year, one of the dorms was demolished, and now it will not be able to be rebuilt.

Not just the facilities but the research itself is imperiled. Last year, the NSF announced that it wouldn't fund new projects for the 2024-25 and 2025-26 field seasons. Only projects that secured earlier funding are proceeding, for now.

Meanwhile, other International powers remain interested in Antarctic research. Both China and Russia have announced new bases in the region, and China, France, and Chile will deploy new icebreakers there.

Antarctica can't wait

As the effects of anthropogenic climate change become more dramatic, Antarctica is the canary in the coal mine.

In an interview with New Zealand's Newsroom, Gary Wilson, president of the Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research, expressed his concerns.

The challenge, he said, is that "Antarctica can’t wait." Global temperature change and sea level rise are urgent problems, and Antarctica is central to stopping this. “Time is just not on our side."

This isn't just overzealous budget cuts; it's part of an intentional policy opposing climate research. It remains to be seen what, if any, research American scientists will be able to conduct in Antarctica in the coming years.

Earlier this week, a massive rockfall hit the West Face of the Dru, near Mont Blanc. The slide would have been considered normal in summer or fall but not in mid-January. Luckily, no climbers were on the wall at the time.

Major rockfalls on the West and South Faces of Dru have been a constant cause of concern since the turn of the millennium. One in 2005 destroyed most of the Bonatti Pillar, one of the most admired routes on the peak.

The situation has only worsened since then. Two years ago, a major rockfall affected the access couloir to the normal route on the South Face. Another big one occurred last summer.

Unusual in winter

Such events are most common in the hottest months of the year, as the permafrost gluing the rock together melts, making the surface unstable. But the slide recorded by several climbers in the area, including well-known photographer Seb Montaz, occurred in midwinter when days are short and temperatures typically remain low.

Glaciologists and climate experts are constantly studying how conditions are evolving around Chamonix. A local alpinist gave us his take on the situation.

Professional guide and Piolet d'Or winner Hellias Millerioux admits the rock collapse was unexpected because it happened during a cold winter day. Otherwise, he says, he wasn't surprised.

"The mountains are changing fast," he said. "Rockfalls and collapses are how the mountains respond to changing conditions, and we will see more and more [of them]."

Millerioux: We'll see more

"As guides and alpinists, we have to adapt," he said. "We need to study conditions carefully and decide wisely what, how, and when to climb."

Millerioux explained that the routes on the Mont Blanc massif, including the normal lines, are in a delicate state. Careful monitoring is essential.

"For example," he said, "I climbed the Walker Spur last summer during a period of good but cold weather. The following week, temperatures rose, and the 0º level went up to 5,000m. In such conditions, venturing onto the Walker would have been extremely exposed to rockfall."

Millerioux admits he's no expert, but his experience tells him that most rockfalls happen on hot days, in fall after a hot summer, and after periods of heavy rain.

"Especially in the granite, the permafrost filling the cracks melts with the high temperatures and the rain, leaving the faces prone to collapse," he noted. "And yet, you must be prepared for the unexpected. The West Face [of the Dru] was supposed to be okay these days, and yet there was rockfall."

Millerioux is not optimistic about the future, especially in places like Chamonix, where the difference in altitude between the town at 1,000m and the highest points (Mont Blanc is 4,809m) is similar to that between Base Camp and the summit on Nanga Parbat.

"I have seen huge rock avalanches while on expeditions in the Himalaya, and sometimes I am concerned because a town is right below the mountains. After the 2015 Langtang earthquake, a major rockslide completely buried the village below. I don't want to think of something like that happening here."

More unstable after each slide

Yet, climbing teams keep scouting the legendary Dru, one of the most iconic peaks in the Mont Blanc massive. As far as Millerioux knows, the North Face of the Dru, one of the six classical North Faces of the Alps, is in good condition. As for the West Face, it is hard to tell from the images which parts and routes may have been affected. The risk is that the latest rockfall may have increased the instability of a face already weakened by previous slides.

The last significant climb in the region happened right at the end of last year. Between December 25, 2024, and Jan 1, 2025, a military team from Chamonix opened Petit Pont, a 1,000m route (ED, M5, 6a, A3) that goes right up the sections of the face where big rockfalls have left the face a lighter shade of grey.

Ice loss in the Arctic has long been a sign of climate change, but an Arctic entirely free of ice has still seemed a long way off.

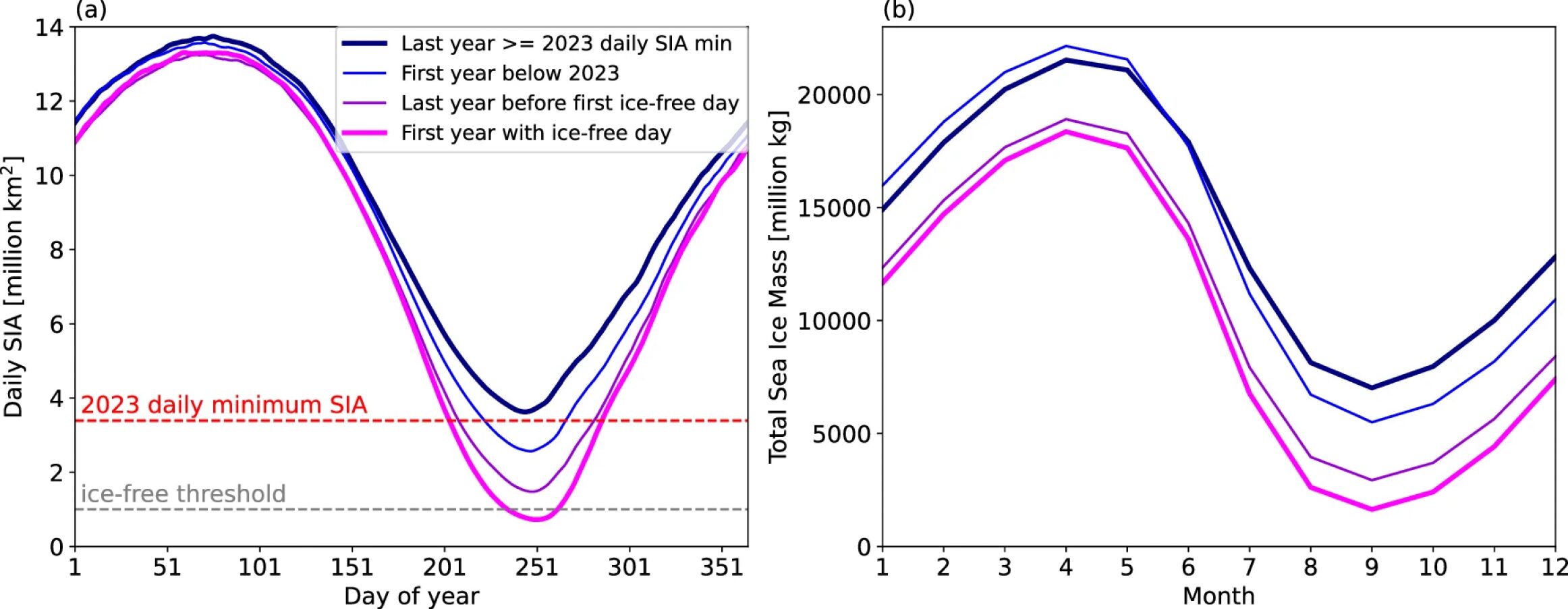

Not so, according to a recent study, which found that the Arctic could see its first ice-free day before the end of the decade.

The term “ice-free” is approximate since small patches of ice will cling to Greenland and the northern edges of Canada long after the rest of the Arctic has melted. Researchers measure the amount of frozen Arctic in “sea ice extent,” meaning areas with at least 15 percent of sea ice concentration. The Arctic is considered ice-free when there are less than one million square kilometers of sea ice.

It is hard to predict when exactly this will happen. Models consistently underestimate ice loss, and global weather patterns affect conditions at the Poles. But this most recent study found it could be as early as 2027.

A powerful symbol

Combining 11 different climate models, researchers Celine Heuze and Alexandra Jahn examined over 300 scenarios for the future of ice in the Arctic. Nearly one-tenth of them showed the first ice-free day occurring within the next 10 years, with the earliest prediction only a few years away. Even conservative models estimate the Arctic will be free of ice within 30 years.

“"The first ice-free day in the Arctic won't change things dramatically," Jahn said, but it would be a powerful symbol of our ability to affect the planet.

Ice loss in general, however, will have very dramatic effects. Due to the albedo effect, by which dark water in the Arctic absorbs the sun's rays, the warming sea will accelerate climate change. It will also cause more extreme weather events.

The first ice-free day, the models show, won’t just come from a warm summer but a warm winter and fall as well. If ice levels reach a low point during winter, climate scientists will know an ice-free day will likely follow the next summer. It won’t be a single day, either. Models suggest the first ice-free period will last between 11 and 53 days.

Is it preventable?

There were also scenarios where things went better for the ice. Changes in emissions can slow down melting, preventing an ice-free day within the 21st century. However, conditions in the Arctic vary wildly from year to year, and especially cold or warm years are difficult to predict, as a number of explorers discovered to their dismay.

According to researchers, the good news is that “if we could keep warming below the Paris Agreement target of 1.5 °C of global warming, ice-free days could potentially still be avoided.”

The Sphinx snow patch on Braeriach in the Scottish Highlands has melted for the fourth year in a row. This is the only 11th time the famous snow patch has melted since the 1700s.

Braeriach is the third-highest mountain in the Cairngorms. The Sphinx sits within a coire -- a glacial hollow from the last Ice Age. Because of this and its presence for hundreds of years, many consider it a remnant of the last Ice Age.

Over the previous 20 years, Iain Cameron -- Scotland’s foremost snow patch expert -- has been monitoring the patch. He says it is a “barometer for climate change.”

This is the first time the patch has melted for the fourth year in a row in over 200 years. The Scottish Mountaineering Club recorded the first full melt in 1933. Over the next seven decades, it disappeared only occasionally. Since 2003, it has vanished eight times.

A sad day today. The Sphinx will melt in the early hours of tomorrow morning, meaning that’s the fourth consecutive year it has done so.

This patch was once considered permanent. It has now melted completely since the 1700s in the following years:

1933

1959

1996

2003

2006

2017… pic.twitter.com/yV5T9yulA4— Iain Cameron (@theiaincameron) October 3, 2024

Cameron blames the scarcity of western-facing storms from the Atlantic. "There’s not as much snow falling in winter," he explains. "Precipitation is mostly rain.”

He visited the ice patch last Thursday. It measured a mere 0.5 meters wide and was gone by the following morning. In snowier decades, the patch was up to 50 meters in diameter.

"I feel both saddened and alarmed," he says. "I'm so used to seeing them year after year that it's hard to see them vanish so often. It’s like visiting an elderly relative."

In his 2021 book, The Vanishing Ice, Cameron explores elusive snow patches around the UK. He believes they might soon be a thing of the past.

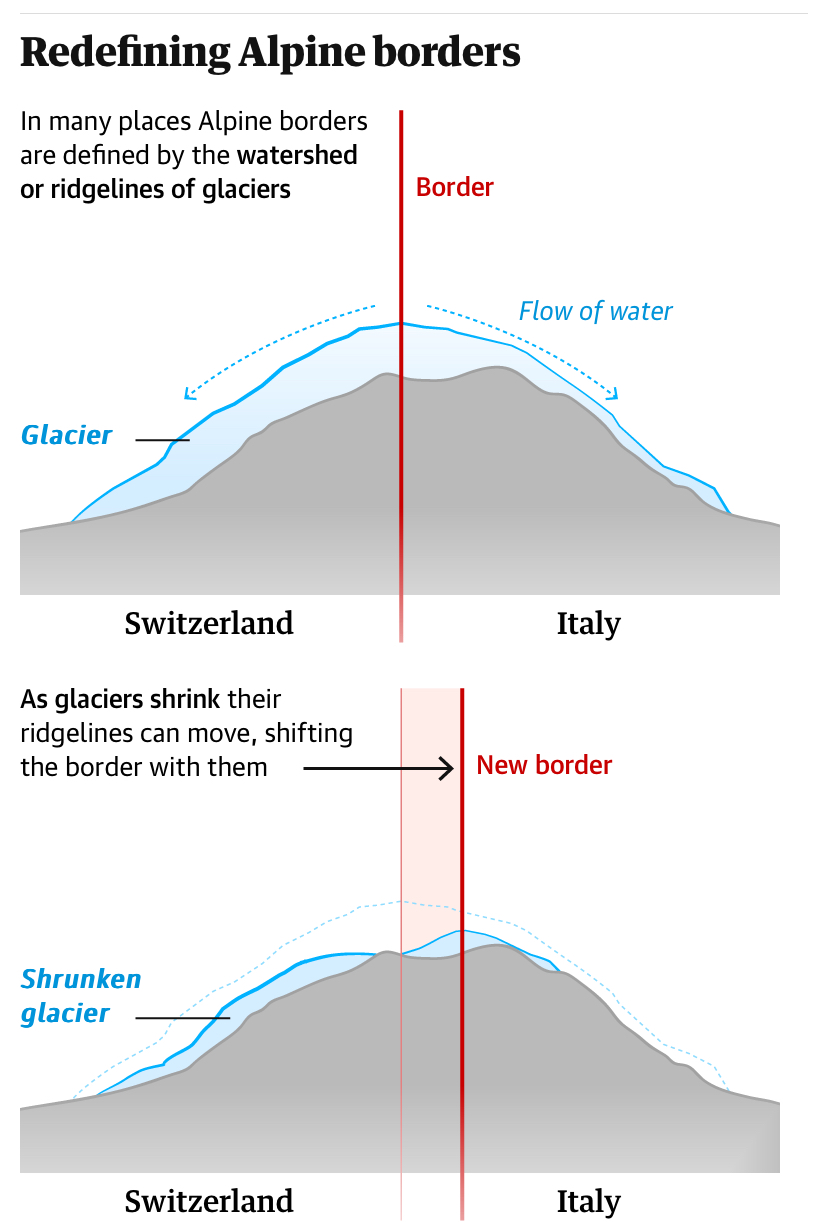

Parts of the 744km-long Swiss-Italian border have always followed the lines that nature has drawn. Now, climate change has redrawn those lines, forcing both governments to redefine those shared sections that depend on the boundaries of glaciers. As these boundaries change, the border must also.

"Significant sections of the border are defined by the watershed or the ridgelines of glaciers, firn, or perpetual snow," the Swiss government said recently. "These formations are changing due to the melting of glaciers."

Both countries are currently considering the proposed revisions. An agreement is expected soon.

Affected areas

Part of the affected area lies below the Matterhorn, close to popular ski resorts. There, the border rejigging will affect the Plateau Rosa Glacier, the Carrel Refuge, Gobba di Rollin, Testa Grigia, and the Zermatt ski resort, where thousands of hikers and skiers cross freely between the two countries every year.

According to Euronews, border adjustments are frequent and generally settled by comparing surveyor data from both countries without getting politicians involved.

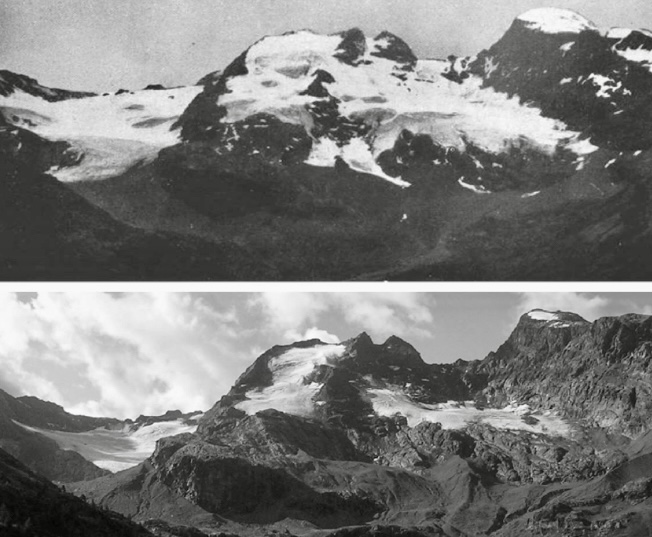

It's no secret that summers are getting hotter, and there is less snow. Swiss glaciers are shrinking so fast that it is unlikely they can be saved. Between 2021 and 2023, eastern and southern Switzerland lost 10% of its glaciers, losing as much ice as it did between 1960 and 1990.

Italy's glaciers are equally afflicted. Dosdè in the Italian Alps has retreated by seven meters since last year.

Grim discoveries

The disappearance of glaciers has also caused the bodies of several long-dead mountaineers to surface. Even a plane that crashed in 1968 and was buried has now emerged from the Aletsch Glacier, according to the BBC.

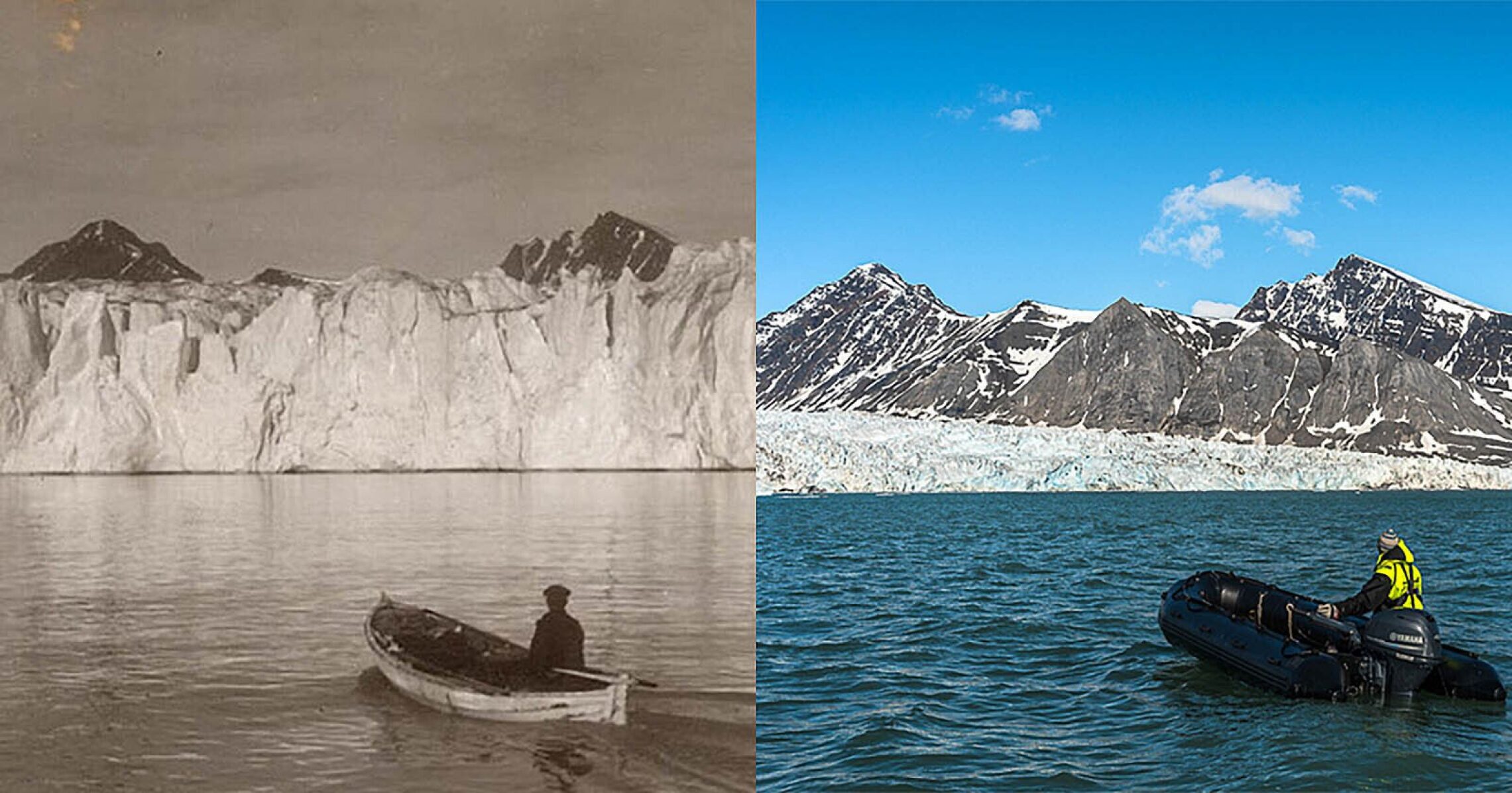

Some veteran hikers, including Duncan Porter below, have shared their photos of glaciers on social media then and now.

Apart from melting glaciers, several climbing routes have suffered massive rockfalls. Some routes have entirely disappeared.

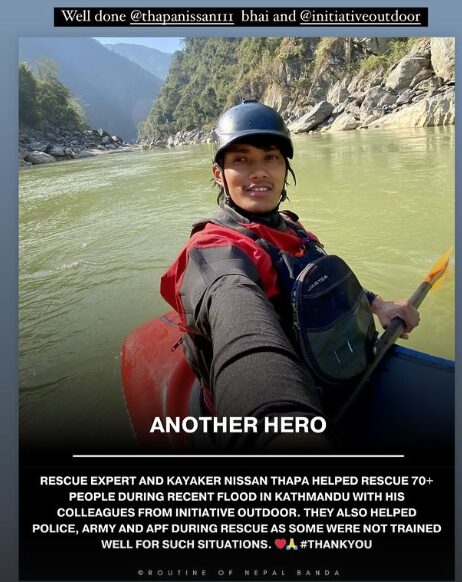

Heavy rains hit Nepal between Thursday and Saturday, causing havoc in several areas of the country, particularly around Kathmandu, where the Bagmati River has breached its banks.

The Home Ministry stated that 192 people are confirmed dead. An additional 30 are missing and 4,500 have needed rescue. Landslides and flooded rivers have blocked several major highways.

Airport remains open

Tourists planning to visit Nepal in the next few days may need patience. Airports remain open but with some restrictions, so international flights may be delayed or rescheduled.

Climbers and trekkers may also face difficulties, such as washed-out roads and delayed helicopter flights. Many helicopters are currently busy rescuing stranded locals. In the Kathmandu Valley alone, roads were blocked or damaged in 57 places, the Rising Nepal Daily reported today. Would-be trekkers should ask their outfitters for updated information about the state of the trails.

Sun returns...

The good news is the rains stopped on Sunday. Yousef Al-Nassar of Kuwait sent these two videos of Namche Bazaar on Saturday after 48 hours of nonstop rain and in yesterday's sunshine.

Like many other climbers in the area, Al-Nassar left town today for the mountains. He intends to reach base camp at Kyajo Ri (6,186m) on the Tibetan border tomorrow.

"I hope I don't find a disastrous situation when I get there," he said.

Al-Nassar told ExplorersWeb that he will climb on his own and attempt a new route up the south face of the mountain.

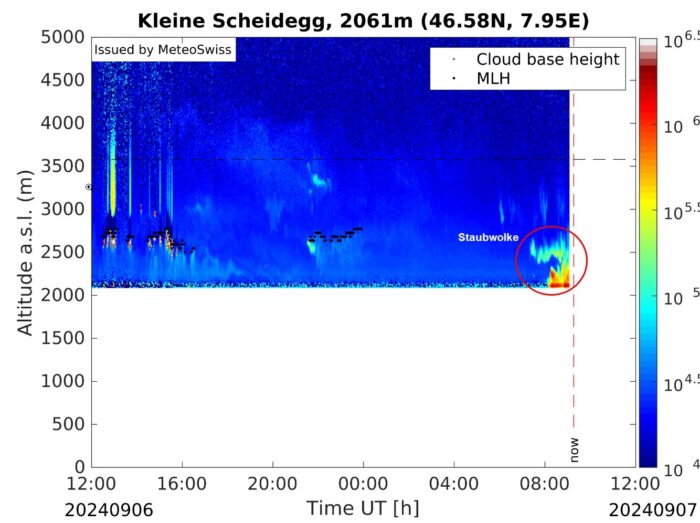

A large boulder that came loose on the upper side of the face triggered the slide. A temperature inversion caused the dust cloud to spread throughout the valley, where it lingered for hours. A celiometer (cloud-measuring device) and webcams at Kleine Scheidegg registered the disturbance, according to @meteoschweiz.

Such events happen in the Berner Oberland from time to time due to thawing permafrost. Until recent years, ice and snow within and between the rocks largely glued together the unstable slopes. As this "glue" melts in the higher temperatures, the rocks become even more unstable.

Bigger than usual

"Such rockfalls are not uncommon," Kathrin Naegeli, media spokeswoman for Jungfrau Railways, told Berneroberlaender.ch. "The last time this happened was at the beginning of August."

Naegeli confirmed that the slide did not affect the Jungfrau Railway, which runs through the tunnel carved inside the Eiger and Monch mountains, or the Eiger Trail along the foot of the mountain. No reports indicate whether the rockfall changed any climbing routes.

While rockfalls are common here, the size of this one was remarkable.

"Rock avalanches are increasing, and events of this size are [unusual]," glaciologist Melaine Le Roi told ExplorersWeb. "Observations around the Alps show permafrost degradation is the main trigger for high-elevation rock avalanches."

The expert noted that the North face of Eiger and the detachment zone are above the lowest limit of permafrost. Read more about permafrost thawing and its effects on alpine faces here.

The Eiger North Face had another major rockfall event just one year ago.

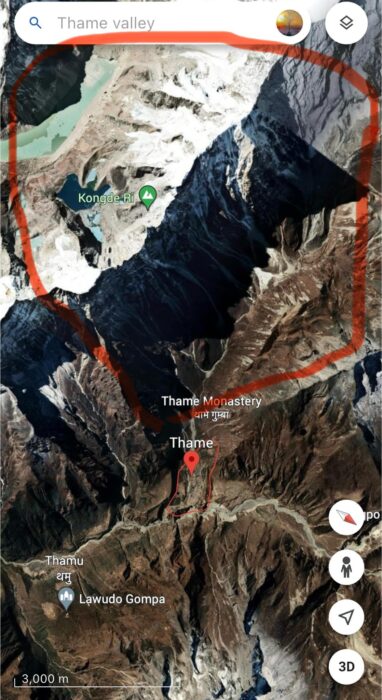

Thame, a village near Everest and the birthplace of legendary Sherpa climbers such as Apa Sherpa and Kami Rita Sherpa, was flooded earlier today. Locals suspect a glacial lake burst its banks and fear further floods.

Thame was flooded at 1:25 pm, Nepal time, after a sudden surge of the Bhotekoshi River. The Bhotekoshi is a tributary of the Dudhkoshi River, the main watercourse of the Khumbu Valley which is directly fed by the Khumbu glacier.

Village destroyed

About 45 families live permanently in Thame. According to preliminary reports, the flood has severely damaged 50% of the village and the remaining houses are uninhabitable. Authorities report one missing person.

The exact origin of the flash flood is unconfirmed, but locals suspect a GLOF, a glacial lake outburst flood.

"There are a couple of glaciers about a two-hour walk above the valley, but because of harsh conditions, it is currently impossible to investigate the source of the outburst," Laxman Adhikari, Ward Chair of Khumbu Pasang Lhamu Rural Municipality Four told the Himalayan Times.

Neighbors fear further floods

Local authorities have warned those living in villages near the banks of the Dudhkoshi River to stay alert. Meanwhile, members of the community are asking for helicopters to scout the lakes up the valley to try and anticipate any further floods.

Among them is Pasang Tsering Sherpa, a local entrepreneur, who considers it essential to find out where outbursts might occur: "If [the flood] comes from the right side of Kongde Ri, it will be very dangerous."

Increasing temperatures are creating huge glacial lakes. These threaten to overflow or, worse, burst because of avalanches from nearby peaks or sudden downpours during monsoon season.

The rains are hitting Nepal hard this summer. Several areas, including some parts of the Kathmandu Valley, were also flooded some weeks ago.

Again this year, huge rockfalls are changing the shape of some of the Alps' most iconic peaks. The latest major slides hit the Dru and the Aiguille du Midi above Chamonix, close to the cable car.

Eddy Veillet, a guard at the Plan de l'Aiguille mountain hut, filmed rocks tumbling down the north face of the Aiguille du Midi. Thanks to the cable car that runs from the center of Chamonix to the summit, it's the most visited peak in the region.

Earlier this week, another major rockfall took place on the west face of the Dru, below the Bonatti Pillar.

This is the second big rockfall this summer on the Dru. The first took place on July 16. Check the video below:

The summer began with plenty of snow on the peaks, but conditions radically changed when a torrent of rain fell at the end of June. It flooded many mountain towns in France, Switzerland, and Italy. High temperatures and dry weather, beginning in the second half of July, followed.

Rockfall is not new, but climate change has increased the frequency and size of these events as the permafrost that glues the rocky faces together melts. Last summer's high temperatures prompted several incidents throughout the Alps.

Check updated posts about the conditions around the Chamonix-area mountains here.

In an occasion both momentous and deeply disturbing, scientists downgraded a glacier in the Venezuelan Andes to just an "ice field." This change in status of the Humboldt Glacier — also called La Corona — makes Venezuela the planet's first contemporary nation to lose all its glaciers.

“Other countries lost their glaciers several decades ago after the end of the Little Ice Age, but Venezuela is arguably the first one to lose them in modern times,” Maximiliano Herrera, a climatologist and weather historian, told The Guardian. He added that Indonesia, Mexico, and Slovenia are likely next up for the dubious honor.

While the ice field formally known as the Humboldt Glacier is still two hectares in area, being a glacier isn't about size — or at least not size alone.

"Glaciologists often use a criteria of 0.1 sq km [10 hectares] as a common definition, but any ice mass above that size still has to deform under its own weight [to count as a glacier]," glaciologists James Kirkham and Miriam Jackson explained to the BBC.

And that's definitely no longer happening to La Corona.

Last man standing

The Humboldt Glacier was somewhat of the last man standing in Venezuela. Located above 5,000m in the Sierra Nevada de Mérida range, La Corona kept company with five other glaciers. By 2011, all five of its companions had already vanished.

That prompted officials and scientists to keep a close eye on the Humboldt. The Venezuelan government even recently installed a thermal blanket over what was left of it in an attempt to halt or reverse the melting process. There was some optimism that the Humboldt might make it to 2030 or beyond.

El Niño

But a nasty El Niño combined with some political turmoil in Venezuela dashed those hopes. By the time the turmoil settled and scientists could resume monitoring the Humboldt, its inherent glacier-ness had vanished.

“In the Andean area of Venezuela, there have been some months with monthly anomalies of 3-4˚C above the 1991-2020 average,” Herrera noted.

Mark Maslin, an earth scientist at University College London, says that the melting of small glaciers such as the Humboldt won't contribute to sea-level rise. But such occurrences represent an ongoing trend. And there are wider implications as well.

"The loss of [the Humboldt Glacier] marks the loss of much more than the ice itself, it also marks the loss of the many ecosystem services that glaciers provide, from unique microbial habitats to environments of significant cultural value," said Caroline Clason, a glaciologist at Durham University.

"That Venezuela has now lost all its glaciers really symbolizes the changes we can expect to see across our global cryosphere under continued climate change."

This morning, a huge avalanche on Manaslu reached Lake Birendra, just southeast of the mountain. It caused the lake to overflow, swelling the water of the Budhigandaki River, which runs toward Samagaon village.

No victims have been reported. However, local authorities have issued urgent warnings to populations down the valley because of the risk of flash floods. Trekkers planning to hike to the lake or along the Budhigandaki River (sometimes called Buri Gandaki) must be especially cautious.

"Initial assessments suggest no immediate threat of further damage, despite the increased water levels damaging a wooden bridge spanning the river," police told The Himalayan Times.

Warning for trekkers

Details remain sketchy, but the lake's location suggests that the slide didn't fall down the mountain's normal route but down its south or southeast flanks. The only expedition planned on Manaslu this spring, a two-person team, received its climbing permit just two days ago. We have no information on them or their objective, but it's unlikely they had time to reach the mountain yet.

However, the Manaslu area in the Gorkha region is a popular spot for trekkers. They will need updated information on the water level of the lake and the Budhigandaki River.

There are those who contend time isn’t real, while most of us spend our lives locked in its regimental advance.

Both those groups received unlikely validation from a recent survey item that could affect timekeeping worldwide.

Climate change is altering time by slowing down Earth’s rotation, researchers found. The key factor is the rate of polar ice melt. And if the warming effect continues at its current pace, the universal timing standard — UTC — will require a tweak by the end of the decade.

“Future Earth orientation shows that UTC as now defined will require a negative discontinuity by 2029,” the study, published in the journal Nature, said. “Global warming is already affecting global timekeeping.”

Nature research paper: A global timekeeping problem postponed by global warming https://t.co/5DU1v0VDy9

— nature (@Nature) March 28, 2024

In short, climate change is slowing down time. And even though the study found things should only slow down by one second every few years, it could wreak “unprecedented” havoc — in the world of computer programming. (Sound familiar?)

Wrinkle in time

Duncan Agnew, a University of California, San Diego researcher and the study’s lead author, described the problem with an assortment of angular velocities. As the earth's 5,400˚ C solid metal core rotates, it affects how the other layers behave. The core has cooled at a constant rate since 1972, the researchers pointed out. As the material cools, it still squishes and squelches around — just more slowly, sort of like refrigerated molasses or grape jelly.

As the magma loses angular velocity, the rest of the layers speed up. This would theoretically speed up time — unless something else slowed it down.

Enter Earth’s polar regions, where spiking temperatures are decimating ice reserves. Observations from NASA show Antarctica has lost 2,500 gigatons of ice mass since 2002 (a gigaton is a billion metric tons).

It’s induced a gigantic weight redistribution, as water drains toward the equator.

"When the ice melts, the water spreads out over the whole ocean; this increases the moment of inertia, which slows the Earth down," Agnew told Radio France.

Officials charged with keeping world time already saw this dissonance coming; they just thought we would reach it three years earlier than Agnew now proposes. And it actually postpones any required response to a possible computer problem that echoes a famous panic from decades ago.

Time warp

Timekeeping took a major step forward in 1967, when the cesium-133 atomic clock became the standard for measuring the second in the International System of Units. Before then, time was astronomical — measured only by Earth’s rotation and relative position in the solar system.

But since atomic clocks use quartz oscillators tuned to electron movement inside the nuclei of atoms, they’re far more accurate. In fact, we’ve added 27 “leap” seconds to UTC since the advent of the system.

Now, though, we’re in uncharted territory — the land of the “negative leap second,” where we face removing time from the world clock for the first time ever. Consensus says we’ll need the negative leap second in 2029; Agnew’s research says 2026.

Either way, it could spell trouble for computer software, which generally only accounts for adding leap seconds, not subtracting them.

"This has never happened before, and poses a major challenge to making sure that all parts of the global timing infrastructure show the same time,” Agnew said, per the BBC.

So give your Y2K shelter keys a jingle and start buying all the toilet paper you can. Or just set your watch back a tick. Or not. Time's not real anyway — is it?

Did you know that “thrawn” is the ability to make the most of whatever you’ve got?

Did you know that Beira, the Queen of Winter, is the mother of all Scottish gods and goddesses?

You’ve had to pause for reflection twice within the first 10 seconds of the film if, like me, you didn’t.

Don’t expect that effect to go away. Lesley McKenna and Lauren MacCallum may not be the Queens of Winter — but they’re pro snowboarders and they've got a lot to say. Contemplative narration dovetails here with an ardent style of riding that's hard to find on piste.

Would you ride that? Yeah, me neither — but then again, I don’t have thrawn.

Stubborn energy

“Stubborn is definitely part of it,” MacCallum says. “A transformative energy, a powerful energy, aye — very needed in these times. The struggle — the thrawness.”

This Patagonia joint is all about the athletes’ deep-rooted backgrounds and contagious personalities. You don’t have to watch much of it to get a strong infusion of both qualities — but you should, because they’re both colorful and compelling.

As much as Thrawn is the story of two athletes, it’s also the story of their town. Aviemore, Scotland is situated in Cairngorms National Park, and it’s a focal point of the country’s ski scene. McKenna knows it well — it’s where her father worked as the first professional ski patroller in the United Kingdom.

Don’t miss wipeouts, sketch moments, and highlights from the Olympian’s long career in the bindings. And hang on for a statement about the future of snow sports in Scotland. MacCallum delivers a snarling, steadfast, aspirational message on the climate change reshaping the country’s famous highlands.

Noting statistics on snowfall decline, she says, “I’m sick and tired of complaining about it in the pub, basically. It brings a sense of unease. We’re gonna have to roll up our sleeves and do it for our goddamn selves.”

Whether or not you lace your boots and cinch your bindings with thrawn each day, you’ve probably felt its call. Watch this short docu to get a booster shot of the mojo that makes these Scottish snowhounds tick.

Thawing permafrost on the granite spires of Patagonia is triggering the same dangerous rockfall that has plagued other mountain ranges. Most recently, some of the pitches on the East Face of Fitz Roy have changed. The objective risk of climbing has also increased.

From difficult to Russian Roulette

A fallen 20-meter slab has affected the first pitch of the Royal Flush route on Fitz Roy (also known as Cerro Chalten), Patagonia Vertical reported. The five bolts and the former belay station are now out of reach. The only way up now is a chimney (6c A0) with several unstable rocks inside it.

"One of them has a guillotine-like edge," Patagonia Vertical warned. "It is not possible to climb it as a chimney because of the blocks...but it could be free-climbed." The site also said that a climbing team will have to clean that section to make it safe again.

It also posted a video of a big rock slide to demonstrate how the rising temperatures have made conditions on Patagonian faces much more unstable.

Royal Flush now even harder

Royal Flush is a high-difficulty, 1,200m route up the center of the East Face of Fitz Roy. It was opened in 1995 by Kurt Albert, Bernd Arnold, Jorg Gershel and Lutz Richter. They free-climbed all except a mixed section and the crux.

Tommy Caldwell managed the first complete free climb in 2005, but he couldn't touch the summit due to dangerous ice conditions near the top. Check this video of Nico Favresse climbing the route:

Studies on the impact of rising temperatures and in particular, climate change in Patagonia have abounded since the 2000s. All note how dramatically the area's glaciers have shrunk and how thawing of the ice "glue" holding the peaks together has made them much more fragile.

Check this video for American climber Tyler Karow's on-site explanation. He shot the sequence last year at the Boeing Ledge on the Central Tower of Paine.

Herders in Mongolia are undergoing an unusually harsh winter — or at least, one that used to be unusually harsh.

“Dzud” winters feature a punishing combination of extreme cold, heavy snow, and high winds. While Mongolian winters are cold in general, these frigid seasons are exceptional. They’re also uniquely threatening to the country’s herders and livestock.

If sheep and goats can’t reach grass beneath heaps of snow and sheets of ice, even the woolliest animals are less likely to survive the extreme temperatures.

To make matters worse, summer droughts often precede dzuds. These conditions happened last year and are worsening due to climate change, the Yale School of the Environment reported.

The upshot is grim. About 190,000 herder households and 64 million livestock animals are “struggling with inadequate feed, skyrocketing prices and heightened vulnerabilities” this winter, according to United Nations officials in Mongolia.

Reports indicated the most snowfall in 49 years and 668,000 livestock dead.

This February, 90% of the country faced the threat.

Snow the height of a ger

That’s after January snowfall amounted to nearly double the long-term national average — an average which has climbed 40% since 1961. Despite government efforts to clear roads, 13,500 households were snowed in and cut off from basic services, as of early 2024.

“I’ve never seen snow that is equal to the height of a ger in my life,” Tserenbadam G., a nomad in her 70s, told Yale’s e360.

“Extreme cold and windy weather weaken animals and lead to starvation; pregnant livestock miscarry or die. Young animals are at greater risk of death,” the UN reported. “The aftermath destroys the livelihood of many herding households.”

According to Yale, a dzud used to occur about once every 10 years. But these days, they have featured in six of the last 10 Mongolian winters.

The winter of 2023-4 especially bad

This year’s is especially severe. In a “white” dzud, very deep snow cuts off animals from grasses. In an “iron” dzud, a rapid, hard freeze follows a brief thaw, which locks pastures in ice. Both sets of conditions exist this winter.

Combined, the UN and Mongolian Democratic Party have proposed over $6 million in aid funding. Relief measures include road clearing and free feed for livestock. However, herders are concerned the resources will fall short of the need.

UN seeks $6.3 million to combat #dzud in #Mongolia. Approximately 90 per cent of the country is facing a high or extreme dzud risk, imperiling millions of livestock and livelihoods. https://t.co/0BiHKhIqiK

FAO/Z. Zolzaya pic.twitter.com/ZcAsdJL9BB

— ReliefWeb (@reliefweb) February 20, 2024

Split between hundreds of thousands of people and millions of animals, the funding would only cover a sack or two of feed per household, herders explained. One sack sustains a sheep for about a week.

And while herders braced for this year’s dzud by slaughtering their weakest animals early, the strategy may further weaken Mongolian rangelands in the long run. Grazing pressure has increased with growing nomad populations, and land fertility is suffering overall.

Mongolia’s Ministry of the Environment and Tourism linked 49 percent of desertification in the country to overgrazing. The rest, officials estimated, is linked to climate change.

Official high-alert conditions will persist until May 15, the World Health Organization advised. Early weather forecasts for March called for more snow accumulation.

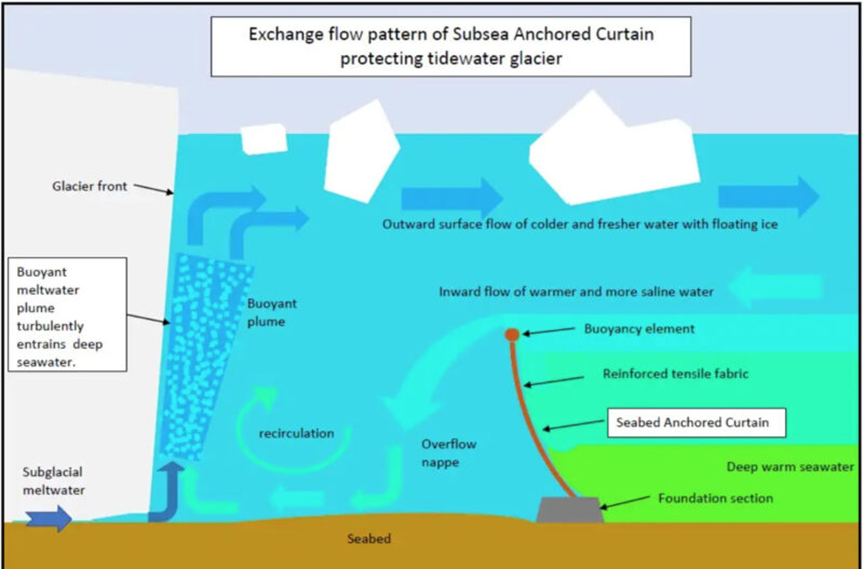

For some years now, scientists have warned climate change has doomed Antarctica's Thwaites Glacier, the world's largest. Also known as the Doomsday Glacier, it is melting at an unprecedented rate. Now one scientist has what sounds like a crazy, desperate plan to save it. He wants to draw a giant curtain around it.

The Thwaites has lost over a trillion tonnes of ice since 2020 and accounts for four percent of global sea level rise. If it melted completely, the sea level would rise by almost three meters around the world.

At the moment it forms a barrier between many other glaciers and warming sea water. If it disappeared, these other, semi-protected glaciers would promptly melt as well.

A 100km long, 100m high curtain

Glaciologist and geo-engineer John Moore wants to erect a 100km long, 100m high curtain around the Thwaites. Contrary to what you might think, it's not to shield the ice from sunlight. The bottom of the curtain would anchor to the seafloor, and the top would float in front of it, creating a makeshift wall in the water. This would keep the deep currents of warm water from reaching the glacier, stopping the melting or at least slowing it down.

In 2018, Moore came up with a similar idea, but instead of a curtain, he proposed a giant wall. Now he thinks the curtain is more feasible. It would be easier to install and remove if it caused unexpected problems.

"Any intervention should be something that you can revert if you have second thoughts," Moore told Business Insider.

Moore and a team from the University of Cambridge are creating one-meter prototypes of the curtain and testing it on a small scale in the lab. They will next test it in a river environment.

In its infancy

They are unsure if the project will work and have stressed that their research is only in its infancy. Testing the curtain on an ever-larger scale will show them if it could reverse or slow down the melting of this giant glacier.

The Seabed Curtain Project hopes to launch a ten-meter version in a Norwegian fiord in 2025. The project will cost somewhere between $50 to $100 billion to set up, plus another $1 billion a year for maintenance.

Some of Moore's colleagues have been highly critical of the project. Speaking to Sky News, geoscientist Martin Siegert said the plan was nonsense and that such “ideas are dangerous, illusionary, and distracting.”

Physical geographer Bethan Davies echoed this. She said that building such a curtain in a polar environment would be almost impossible. Others have said even if it works, it will merely slow the inevitable.

Moore admits that this is not a permanent solution, but it is better than just giving up. "We need to do something,” he said.

As the days get hotter across Europe, the Alpine ibex's behavior and daily routines are changing.

A research team from Sardinia has been using GPS trackers to monitor the daily movements of the goats between May and October since 2006. They tracked 47 goats across two national parks and amassed 13 years of data.

Typically, ibex make their way down the mountains during the day to feed at lower altitudes. But this is happening less and less.

Heat more pressing issue than predators

Instead, the goats are often foraging at night, even in areas with high concentrations of nocturnal predators. There is minimal cover in the areas where ibex feed and wolves patrol these areas at night. The ibex seem to have decided that avoiding the heat is more crucial than avoiding predators.

"We expected higher levels of nocturnal activity in Switzerland where wolves [one of the ibex’s main predators] were absent, but we found the opposite. We found that activity is higher in the areas with wolves," co-author Francesca Brivio told The Guardian.

Nocturnal activity brings other risks too. Navigating steep mountain faces is significantly harder in the dark, and the goats are not particularly well-adapted to a nocturnal lifestyle.

"Their movement in the rocky slopes where they live is probably more difficult [at night], which could make the foraging and foraging strategies less efficient," Brivio explained.

Our changing climate is forcing many species to adapt. However, researchers are worried that the ibex are making themselves both more susceptible to predation and less able to feed properly in the dark.

Ibexes are particularly vulnerable because of their low genetic diversity. During the 1800s, numbers dropped dramatically because of hunting. At one point, only 100 wild individuals remained. Hunting bans helped numbers rebound, and there are now tens of thousands of Alpine ibex in Europe.

Until now, no one was sure why the Earth slipped into an extreme ice-age 717 million years ago and stayed that way for 56 million years.

Now researchers in Australia may have solved the mystery.

Using computer modeling, they analyzed how the continents moved over time. They believe that the sudden drop in temperature was due to a decrease in carbon dioxide emissions. Carbon dioxide traps the sun's heat. If the carbon dioxide in our atmosphere plummeted, it could cause the "Snowball Earth" of 700 million years ago.

But what caused carbon dioxide levels to dive so dramatically? And why did it last for 56 million years? Says Lead researcher Adriana Dutkiewicz, “These days, humans are having a large impact on CO2 in the atmosphere. But back in time, there were no humans, and so everything was basically modulated by geological processes.”

They suspected that the changing carbon dioxide levels might be from volcanic activity. Or rather, a lack of it.

The team looked at the movement of the tectonic plates after the breakup of Ronda, the ancient super-continent. The model showed that as the smaller continents shifted away from each other, the length of the mid-ocean ridge changed in length. A second computer model then analyzed the amount of carbon dioxide emitted from the underwater volcanoes along the mid-ocean ridge.

The modeling showed that an all-time low of volcanic carbon dioxide emissions coincided perfectly with the start of this so-called Sturtian ice age. The amount of atmospheric carbon dioxide was approximately half of what it is today. For the next 56 million years, the carbon dioxide remained relatively low.

Said co-author Dietmar Müller, “We think the Sturtian ice age kicked in due to a double whammy: a plate tectonic reorganization [minimized] volcanic degassing, while simultaneously a continental volcanic province in Canada started...consuming atmospheric carbon dioxide.”

Though the models seem to explain that mysteriously long ice age, it is hard to prove. No one knows what the ancient seafloor looked like. “One thing about geology, there are no definite answers," says Dutkiewicz. "But...we can suggest that this was a very likely process.”

What could take down a prehistoric ape the size of a pickup truck? Don’t look at a rugby player, pro wrestler, or even any natural predator.

Just check the weather.

Gigantopithecus blacki was the largest primate that ever lived. “Giganto” stood three meters tall and weighed about three to four times as much as a human at 200-300 kilograms. The ape lived in southeast Asia about two million years ago — until it sharply declined and disappeared.

Giganto’s downfall began about 300,000 years ago, but until now no one could suggest a compelling reason for it. Now, new research points to climate change. It forced dietary adjustments that the huge creatures couldn’t adjust to.

A team led by Kira Westaway of Macquarie University published the recent work in the prestigious journal Nature. Right away, the team’s findings chipped away at a common misconception about Giganto’s extinction.

“It was assumed that the deterioration in forests was the cause of its demise as it couldn’t live in open grasslands,” Westaway told the Guardian. "But our study shows that this [shift to savannah] occurred at about 200,000 [years ago] when G. blacki was already extinct."

Favorite fruits disappeared

Instead, Westaway’s group found that a gentler shift in Giganto’s habitat from deep forests to medium-density savannah triggered the die-off. Climate change seemed to account for the novel landscape.

“We’re getting a very strong wet season and a very strong dry season,” said Westaway.

The upshot: Fruits on which Giganto had grazed freely throughout the year suddenly became scarce during dry periods.

The team investigated the evolving diet of Giganto by examining wear patterns on its teeth and its internal chemical composition. Fallback foods were the focus. What did Giganto eat as its staple foods disappeared?

For comparison, the team looked at teeth from a Chinese orangutan, a similar animal that went extinct later. While the orangutan shifted to leaves and flowers from the forest canopy, the giant ape opted for a paltry backup diet: bark and twigs on the forest floor.

Mobility limited the animal’s foraging range, the team found. Soon, Giganto populations faced challenges, and between 295,000 and 215,000 years ago, they had disappeared.

Thinking of taking the kids to see the Ice Grotto at Chamonix's Mer de Glace this Christmas? Or planning to ski down the Vallée Blanche? Make sure you bring crampons, harness, and ice axe, and that you know how to use them.

La Chamoniarde, Chamonix's organization for mountain safety, regularly updates on alpine conditions near Chamonix. It warns about restricted access to and from the glacier while a new cable car is built.

Tourist hotspot

The Mer de Glace Glacier is one of the most popular tourist attractions in the Chamonix Valley, thanks to its easy access and the presence of a spectacular ice cave. Visitors usually reach it via a combination of the Montenvers trail, a cable car, and some stairways and ladders to the glacier.

In winter, the glacier marks the end of the ski descent of the Vallée Blanche, the 23km-long downhill that starts from the top of the Aiguille du Midi cable car. It is a 2,800m descent from the top of the lift to Chamonix.

Shrinking glacier

Unfortunately, the Mer de Glace has suffered from the devastating effects of climate change. The ice is disappearing at an alarming rate.

For a decade, the old gondola linking the Montenvers train station and the glacier, built in the 1980s, put visitors directly on the ice. Eventually, Chamonix had to add some metal steps to the rocky glacier side, then more every year. In 2021, over 550 steps lay between the end of the gondola and the ice surface.

Old stairway closed

Finally, in November, the gondola lift closed forever. A new cable car leading to a different spot, 600m further up the glacier, will replace it. The ice is supposed to last longer there.

The old stairway is now closed and off-limits. Until the new lift opens next month, the only access to the glacier is by via ferrata (the yellow route on the main image and the green line on the map below). This requires safety lines, helmets, crampons, and ice axes.

What about skiing?

Mainly, it depends on snow conditions. It's ideal to have enough snow to ski down to Chamonix and skip the lift and the train altogether. However, that is not typically the case. Most of the time, skiers end up at the glacier and climb up the stairs to the now non-existent lift.

Since that is no longer an option, the alternative is to head for the Buvette des Mottets and the trails through the woods to town.

However, the lift that conveys skiers from the Vallée Blanche to the Aiguille Du Midi only opens on Dec. 23.

"Even with the lift open, conditions during the first weeks of winter are tough," UIAGM guide Michel Gonzalez told ExplorersWeb. "We only guide a few people, no more than two per guide, and we make sure they are experienced enough.

Have a look at the whole ski run and the arrival at the Mer de Glace and the ice cave.

A Japanese scientist studying thinning sea ice has died when he fell through the ice in Northwest Greenland.

Locals had warned Tetsuhide Yamazaki that ocean currents were fast near Siorapaluk, the world's northernmost village. They said that he should not go this early in the season. Although Yamazaki was experienced, he went. This is the Dark Season in Siorapaluk, and the sun is below the horizon until February, so visibility is poor.

When he didn't return, a search party found a hole where he had fallen through some shuga, or porridge ice, according to ExplorersWeb writer Galya Morrell, who is in touch with the villagers. There was no trace of him.

Despite its remoteness, little Siorapaluk, population about 60, has been a popular destination for Japanese scientists of all stripes for years. That is thanks to the amazing Ikuo Oshima. In 1972, Oshima moved to Siorapaluk from Tokyo after seeing photos of it in a book. He fell in love with the place, married a local woman, and lived the traditional hunting life of that remote Inuit region.

Now a young-looking 76, he is considered the most knowledgeable hunter in the village. His friendliness and willingness to help has drawn other Japanese to Siorapaluk, for briefer periods, to study.

Is society ending due to climate change? The internet says "definitely yes," and "definitely no," and every shade of "maybe."

One group of researchers wanted to peel back a few layers. Climate change does destroy some cultures — but why? And, more pressingly, why do others survive these traumatic fluctuations?

Austria’s Complexity Science Hub performed the peer-reviewed study, sourcing an ambitious database of significant moments in human history. The group pulled data on 150 calamities throughout time periods and regions from Seshat, which aims to catalog “human cultural evolution since the Neolithic.”

The key insight is bad news for many of us around the world: Cohesion is the main ingredient in social survivability, the researchers found.

Rome's declining plague survival

“Inequality is one of history’s greatest villains,” Daniel Hoyer, a co-author of the study and a historian who studies complex systems, told PopSci. “It really leads to and is at the heart of a lot of other issues.”

The team draws the argument that we need a strong capacity for teamwork to meet the huge challenges climate change can cause.

For instance, high volcanic activity in the early centuries AD helped cool temperatures, which led to the epidemic waves that crippled the Roman Empire. The Republic survived the first one, 165 AD’s Antonine Plague of smallpox, through community resilience — even though it lasted for a generation and was far deadlier than COVID-19, according to the Smithsonian.

Emperor Marcus Aurelius reinforced cities and towns that the pestilence cleared out, inviting migrants to work the fields and even promoting the sons of freed slaves to replace felled aristocrats.

But the third century’s Plague of Cyprian tore into a Roman Empire in flux. Civil wars and outsider invasions roiled it, and a seismic shift to Christianity under Emperor Constantine loomed. Rome survived again, but the Plague of Justinian in the sixth century proved too much.

View this post on Instagram

This likely genetic precursor to the Black Death laid the empire low with death rates soaring to 25-40% in Constantinople, according to The Collector. The Western Roman Empire had collapsed two centuries earlier, and invaders had pillaged Rome itself twice. Emperor Justinian had involved his army in reclaiming lands, but when the population rotted from the inside out, attackers closed in.

Too many Maya, not enough water

General consensus agrees that other factors did contribute to these pandemics, like increasing global trade. So what about other societies that suffered from more direct climatic shifts like droughts, famines, and floods?

The Maya had heavily populated the interior uplands of the Yucatan peninsula by around 750 AD. But seven successive droughts then occurred, and they had virtually disappeared from the area by 1000 AD (when the civilization itself effectively collapsed).

The Maya kept growing and populating, though, throughout the first five major dry spells. Why did they succumb to the last two?

Looks like they were overpopulated, evidence suggests. According to the Harvard Gazette, dense cities of 60,000-100,000 people sucked up water sourced unsustainably from wetlands and forests. The Mayans’ agriculture techniques made the problem worse, and the cyclical droughts finally overcame their ability to survive.

Poor design, the report suggests, made their choked cities unlivable under ecological pressure.

“You need to have social cohesion, you need to have that level of cooperation, to do things that scale — to make reforms, to make adaptations,” Hoyer, the Complexity Science Hub co-author, told PopSci. “Whether that’s divesting from fossil fuels or changing the way that food systems work.”

The climate will kill us, and the mechanism will be greenhouse gas emissions, a new paper promises — albeit, 250 million years from now.

A study published Monday in the journal Nature Geoscience models an oncoming supercontinent that will prove unsurvivable. Pangea Ultima will cause “conditions rendering the Earth naturally inhospitable to mammals,” the University of Bristol team found.

Pangea Ultima’s formation would produce massive carbon dioxide, doubling the amount in today’s atmosphere. But that’s only one piece of the puzzle. The aging sun will also scorch the planet with 2.5% more wattage than today. And the vast inland areas would experience temperatures too extreme to tolerate.

What would this world look like? Basically, the continents would squish together, as seen on a conventional map. If you were anywhere around latitudes of about 30 degrees, you’d be having a very bad time. Average summer highs would reach a temperature represented by a color that does not exist on the scientists’ maps — which tops out at a burned meat-colored 60˚C.

When the age of mammals ends

Right now, the researchers call 66% of the planet “habitable.” By the year 250,002,023, that number narrows to 8%.

The event would bring a resilient lifeform to its knees. Mammals have inhabited “nearly every terrestrial biome” on earth during about 310 million years of existence, the paper points out. That’s about twice as long as dinosaurs, and we outlived their mass extinction and others. Heavy climatic fluctuations, like multiple ice ages, have also taken place during our tenure.

Interestingly, the researchers found this could be the only thing that mortally threatens mammals during the next several billion years. They even point out that no other factors will even injure the dominance of earth’s most prolific vertebrates.

Human-caused climate change does exist, they acknowledge. But “it is unknown whether or when [mammals] will ever reach a climatic tipping point whereby their ascendancy is threatened.”

At least not until a “runaway” greenhouse effect inevitably takes over in billions of years. In it, “all life will eventually perish.”

Before this physiological Armageddon, it does look like life on the blue planet will experience a pretty wide window of existence. What that might look like is anybody’s guess.

Lead author Alexander Farnsworth teased the possibility of our replacement, but didn’t hazard a guess at what might do it.

We are the dominant species but Earth and its climate decide how long that lasts,” Farnsworth told The Guardian. “What comes after is anyone’s guess. The dominant species could be something completely new.”

Alpinist Robert Jasper reported today that a large rockfall cascaded down the North Face of Eiger. According to Jasper, the historic Ghilini-Piola Direttissima route, and possibly also the new Renaissance route, have been affected.

On the Ghilini-Piola Direttissima, first climbed in 1983 by Rene Ghilini and Michel Piola (6b, A4, 1,400m), a huge rock pillar collapsed at pitch 22. It smashed the entire wall section below, according to Jasper. He did not report any injuries.

As we reported last week, Peter von Kaenel and Silvan Schupbach opened the 30-pitch, 1,220m Renaissance route just last month. They placed no bolts and only left behind eight pitons. This route follows the steep Rote Fluh, near the Ghilini-Piola Direttissima and the Czech Pillar.

Rockfall on the Matterhorn too

Yesterday, Sept. 10, 2023, there was also a big rockfall in plain view on the Matterhorn's South Face, according to Italy's Newsbiella. Local sources confirmed that no one was on that part of the face at noon when it occurred.

The normal route was unaffected. A further rockfall occurred on the Swiss side of Matterhorn, around the Zmutt ridge. Because of the high temperatures and the instability, all guides decided against climbing the mountain with clients, even via the normal route.

As Newsbiella points it out, these rock slides are not surprising, since the temperature has not dipped below freezing even on the summits for many days.

Here is the video on the rockfall on the Matterhorn, recorded by Luciano Canova.

The longest-lasting snow patch in the UK has completely melted for just the 10th time in 300 years. It has been around longer than three centuries, which is when records of the Sphinx patch began.

The Sphinx is located in a sheltered part of the third-highest mountain in Britain, Braeriach Munro in the Cairngorms, Scotland. The patch of snow has now disappeared five times within the last six years.

A famous perennial patch

Until 100 years ago, everyone thought the snow patch was a permanent feature on the mountain. It exists in a coire, a glacial hollow that formed during the last ice age. Even in the warm summer months, it used to stay cool enough to maintain snow.

The first confirmed record of it fully melting was in 1933, then again in 1959. Before this, it is thought to have melted in the 1700s for the first time. It was known as a perennial patch because it lasted for more than two years at a time.

Since 1996, its disappearance has become much more common. Over the last three years, it has fully melted each summer, meaning that it is now classed as a seasonal snow patch.

It is with a heavy heart I report that as of today the Sphinx has gone *again*. What 100 years ago was considered to be a permanent feature of our hills has vanished for the 10th time. Five of these have been since 2017.

A sad day.

Joe Glennie pic.twitter.com/IdM97aog8J

— Iain Cameron (@theiaincameron) September 6, 2023

Iain Cameron, a snow expert who monitors the patch, confirmed its 10th disappearance. He said that it is "beyond reasonable doubt" that global warming is the cause of its more frequent melting.

After it disappeared in 2021, he told The Guardian, “What we are seeing from research are smaller and fewer patches of snow. Less snow is falling now in winter than in the 1980s and even the 1990s.”

For those in the UK, it might not be surprising that the snow patch has melted this week. In the last seven days, we have had the hottest day on record this year and set the record for the hottest September ever.

Cameron believes that it will now become a rarity for the Sphinx patch to survive through the year. In 2020, a report by the Cairngorms National Park stated that snow cover has been decreasing on the mountain since 1983. By 2080, there will likely be no snow on the mountain at all.

It's not news that climate change is severely affecting the European Alps, but studies quantifying the economic impact of increasing average temperatures are still scarce. When they are published, the conclusions are scary.

"Without snowmaking, 53% and 98% of the 2,234 ski resorts studied in 28 European countries are projected to be at very high risk for snow supply under global warming of 2 °C and 4 °C, respectively," a new article published in Nature states.

Shorter seasons

So, if average temperatures rise another 4°C, skiing in Europe is essentially over. Of course, there is an "if" in the previous sentence, but every ski-lover in Europe knows that ski seasons are progressively growing shorter. Rain in the middle of winter seems more common, spoiling conditions on the runs. Last year, the beginning of the season was troublesome, not only in southern Europe but also in the most visited ski spots in the Swiss, French, Austrian, and Italian Alps.

As the study explains, the changes are not regular: warming is hitting lower or more southern resorts particularly hard. In such places, snow canyons have become an essential part of the infrastructure, as numerous as ski lifts and snow-cats.

Meanwhile, the resorts' maintenance technicians use their skills and resources. They shovel thick layers of wet snow upside down to get drier layers to the surface before the skiers start gliding down. They snow-farm too, piling up and trying to preserve the remaining snow at the end of the ski season, so they can use it the following winter.

Shooting snow is not enough

Snow guns have become increasingly popular in ski resorts across Europe, even in places where machines were not needed just a few years ago. In some lower or southerly spots, business is entirely dependent on artificially produced snow. The question is how long this method will be sustainable, or even profitable.

The average snow gun is capable of producing snow at nearly 0ºC and some new models are capable of spraying solid snow even at 4ºC. However, their use requires lots of power and water.

"While it represents a modest fraction of the overall carbon footprint of ski tourism, snowmaking is an inherent part of the ski tourism industry and epitomizes some of the key challenges at the nexus between climate change adaptation, mitigation, and sustainable development in the mountains, with their high social-ecological vulnerability," the article explains.

A long heat wave in southern and central Europe is having a serious impact on the Alps, affecting some of the most popular spots.

In the Ecrins massif (French Alps), a huge rock slide has buried the trail to the refuge housing climbers for Mount Pelvoux, one of the area's most visited peaks. Further slides and climate change-related issues have forced the closure of three more huts in the last three weeks, glaciologist Melaine Le Roy reported on X (formally Twitter).

Chatelleret Hut closed because of flash floods and Selle Hut had to stop operating because the water source to the hut dried up. Now a rockslide down Celse Nievre Valley has cut access to Pelvoux and Sele huts. You can see the rockslide in the video below.

Be careful on Mont Blanc

In the Chamonix area, conditions have rapidly worsened, La Chamoniard reports. The zero isotherm is currently around 5,000m, meaning snowy ground doesn't ice up during the night, even on the 4,000'ers. This means softer snow, weak snow bridges over hidden crevasses, and unstable terrain on the ridges.

The High Mountain Rescue Group confirmed the dangerous conditions in their latest report, issued on Monday.

Among the worst affected areas is Mont Blanc's normal route. Several crevasse falls have been reported at the Dome du Gouter and a major slide yesterday at 5:30 am down the Col du Gouter (also known as the Bowling Alley) on Mont Blanc's normal route resulted in a rescue.

If the situation doesn't change, soon Mont Blanc will be extremely demanding or not possible, officers warn. "Make inquiries, adapt your choice of activities and outings, and don't hesitate to postpone certain climbs," La Chamoniard suggests.

Yesterday, a new rockslide occurred on the north face of the Aiguille de Midi, between the Frendo Spur and the Mallory route, shocking trekkers at Plan de l'Aiguille. The debris cloud could be seen through the Chamonix valley, Le Dauphine Libere reported.

Trekking also hazardous

Landslides do not only affect alpinists climbing big mountain faces. They also affect trekkers and hikers passing below the peaks. The video below by guide Jaime Escolano shows a rockslide at the Croda Rossa in Italy's Dolomites.

Just seven days ago, I crossed the base of Croda Rossa with friends, passing through the area that would be hit by the rockfall.

Heavy rainfall in India's Himachal Pradesh has caused huge landslides. At least 30 people have died, and the casualty count is increasing.

The strong monsoon has brought huge floods and landslides, destroying several buildings. In Shimla, a Shiva temple came down in the flood waters, killing nine, including three children.

According to local news, it's feared that nearly 50 people might be buried under the debris. Rescue efforts are currently underway.

This is just one of a series of weather-related disasters to strike the Indian Himalaya in recent years.

Cloud burst in Himachal Pradesh | India | heavy rainfall | landslide | #HimachalPradesh #Himachal #HimachalFloods #Uttarakhand #HeavyRain #HeavyRainfall #landslides #floods pic.twitter.com/LDVSDSVDh1

— Mukul Negi (@Mukulnegi009) August 14, 2023

Trying to attract sponsors by wrapping expeditions with awareness-raising campaigns for good causes is a common expedition tactic. Sometimes, it gets out of control.

Such was the case of the team who came up with the idea of justifying a trip to Greenland by bringing a chunk of an iceberg in a fridge all the way back to southern Spain, just to let it melt in the middle of a street.

After a trip to southern Greenland, the organizers shipped a 15,000-kilogram piece of iceberg to Spain in a refrigerated container at -20ºC. The cargo is currently on its way to the Malaga Coast, in southern Spain. And why the fuss?

"So citizens can observe how the iceberg melts down, and thus raise awareness about global warming," one organizer told Cope Radio.

For all the tourists sitting on terraces suffering the effects of withering Spanish heat over gin and tonics, a summer hot enough to melt icebergs will hardly come as a surprise. Calculating the carbon print and energetic cost of the stunt could be actually more surprising. At least, so think Malaga's environmental associations.

Greenwashing

"This is a greenwashing operation organized by Manuel Calvo and supported by Malaga's local government," Malaga's section of Ecologistas en Accion (Spain's biggest association of ecological groups) said.

They criticized the waste of energy and resources, as well as the iceberg-melting plan. "It is like trying to raise awareness against animal mistreatment by organizing a bullfight," they said.

The environmentalists also noted that the organizers have simply justified "a joyride in Greenland" and taken advantage of some young cancer survivors.

The organizer, Manuel Calvo, promoted the trip as a mission in which he would take five former cancer patients between 15 and 17 years old for the experience of a lifetime. Calvo also took his own son and daughter as coaches.

Tourism disguised as a 'mission'

They toured part of Greenland's southern fiords for two weeks by motor boat. They did a little kayaking and hiked up to a nunatak (a peak that pokes up above the ice sheet). A number of adventure-travel agencies, based in Spain and elsewhere, offer similar tours.

This article was originally published on GearJunkie.

Yvon Chouinard may have given away his company to fight climate change, but he's hardly taking a vacation.

The Patagonia founder figures large in the company's latest documentary about improving our collective stewardship of the environment. "Home, Grown" follows architect and climber Dylan Johnson and a small crew as they build two houses in California. The catch? They're using straw bales that would otherwise have gone to waste.

When building materials contribute an estimated 5-15% of global greenhouse gas emissions, according to a Patagonia press release, finding sustainable ways to build will be a necessary part of addressing climate change.

"Which begs the question: What if we used materials that not only take less carbon to produce, but also can capture and store carbon?" the company said in a statement.

Folksy wisdom meets modern problem-solving in this short doc about yet another way we could do better by Mother Earth.

Yesterday at 105˚F in my central Texas city, I watched a haggard man remove an irrigation valve cover in a parking lot median, open the valve inside, and stand directly in the resulting blast.

He’s not the only one getting creative to beat this summer’s exceptional heat. But where he looked underground for relief, someone else is looking the other direction — by a very long way.

One University of Hawaiʻi astronomer thinks we can cool Earth by tying a giant umbrella to an asteroid, then stationing it between the earth and the sun. A peer-reviewed paper detailing the idea, called “Solar radiation management with a tethered sun shield,” appeared yesterday in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

There’s no indication that work on this counterweighted solar shield is underway, but if an effort did succeed, it could “mitigate climate change within decades,” according to the University's UH News.

It’s pretty conceptual. Take it from study author Istvan Szapudi.

Weight is the main obstacle

“In Hawaiʻi, many use an umbrella to block the sunlight as they walk about during the day. I was thinking, could we do the same for Earth and thereby mitigate the impending catastrophe of climate change?” Szapudi told the University.

For a structure, the paper suggests that multiple shields “could open up in a petal configuration” once in orbit. Connected to counterweights, “a slow opening allows the gradual filling of the counterweight with lunar dust or asteroid material.”

Feasible or not, it seems like a cool idea. As the paper points out, plenty of scientists have proposed cooling the planet with shade structures in space before. Realizing it’s cooler in the shade doesn’t take a — ready for this one? — rocket scientist.

But weight is a fatal flaw. To deflect away 1.7% of the sun’s energy, we’d need a shield that weighed about 32,000 tonnes, Szapudi's team calculated. Today’s strongest rocket systems can only deposit about 45 tonnes into low orbit.

Not only that, the structures would need to stay at a steady weight and the proposed “tethers” would need to remain attached to keep them all in orbit.

“If multiple tethers hold the shield, breaking one or two would not create an accident,” the paper postulates. But it “has enough weight to wreak havoc if it accidentally crashes on Earth.”

It also notes that sourcing cables strong enough to do the job is a major obstacle.

With a glimmer of intuition, though, the proposal does at least indicate a solution to the problem at hand. If you need thing A in place B but it takes too much work to bring thing A with you on your way there — then use what you find when you arrive.

Until then, I know just what parking lot median to visit for a cool-down right here on Earth.

Swiss police have identified the remains of a mountaineer found two weeks ago in the Swiss Alps.

On July 12, some mountaineers found a body on the Theodul Glacier in the Pennine Alps, near the Italian border. Yesterday, the police announced that DNA has revealed that the body belongs to a 38-year-old German mountaineer who went missing in September, 1986.

From their records, police now know the name of the man, but those details are not public.

At least 300 people (including hikers, skiers, and mountaineers) have gone missing in the Alps in the last century. It seems that every year now, human remains emerge from the quickly melting ice.

On June 11, a huge chunk of the summit of Fluchthorn (also known as Piz Fenga) collapsed. The 3,399m mountain lies in the Silvretta Alps on the border between Austria and Switzerland. Thousands of tons of rock fell because of thawing permafrost.

Miraculously, local authorities report no injuries. Onlookers recorded the collapse.

This is not the first collapse in the area. Last month, authorities evacuated residents of the Swiss village of Brienz because of rockfall danger.

After a scorching summer, Europe is now having one of the warmest winters ever registered.

Hopes for alpine ski resorts faded with the arrival of the New Year and what has so far been a scorching January. Temperatures in Switzerland were 20˚C on Monday, and record highs were also recorded in the Czech Republic, Germany, and Poland.

In France, the night of December 30-31 was the warmest since records began. Temperatures soared to nearly 25˚C in the southwest on New Year's Day, reports Yahoo News.

Artificial snow or nothing

Warm winters are not new to Western European mountains, especially early in the season. But this year is the worst ever. Most resorts in the Alps and the Pyrenees are relying on artificial snow. For some of them, it's been too warm even for that. Some have closed temporarily or for the rest of the season.

The problem is that artificial snow cannons need temperatures lower than about 4˚C in order to work. Meanwhile, central Europe has been baking in a heat wave since New Year's. On January 1, temperatures reached 19ºC in Budapest, 25º in southern France and the northern coast of Spain, 19ºC in the usually freezing Warsaw, almost 20˚ in the Czech Republic, and 20ºC in Liechtenstein, according to ABC.

The popular ski jump competition celebrated every January 1 in Garmisch Pasterkirchen, Germany took place in all-artificial snow and plastic pads. Check the video below:

Second stage, second win for Halvor Egner Granerud! pic.twitter.com/xjc3HTFyve

— FIS Ski Jumping (@FISskijumping) January 1, 2023