In a new study, a team of biologists found that participants' breathing patterns were so unique that they could identify them with almost perfect accuracy.

But not only that; the study also showed that these "respiratory fingerprints" could predict physical and mental traits like Body Mass Index (BMI) and mental illness.

Counting breaths

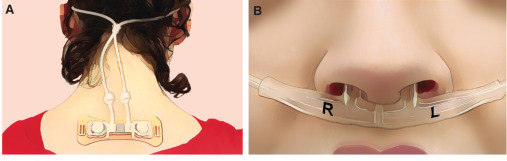

To measure breathing patterns, researchers strapped a special device onto 100 subjects for 24 hours, logging every inhale and exhale. AI analysis then turned the data into a distinct pattern, which then matched breathing to participants with 96.8% accuracy. The breathing data also indicated whether a subject was asleep or awake, and seemed to indicate Body Mass Index.

Researchers invited the subjects back three months later for another trial. They found that their breathing patterns hadn't changed much, indicating that the fingerprint was fairly stable.

Participants filled out surveys designed to measure depressed, anxious, and autistic traits. All three conditions have possible links to respiratory dysfunction.

Breathing exercises are widely used to reduce anxiety. But respiratory fingerprints could have a much broader application. "We envision application of respiratory fingerprints across various areas of medicine," the paper predicted.

The future of respiratory fingerprints

Even the most fundamental physiological processes, like breathing, aren't fully understood. We are still learning how changes to breathing and air conditions affect the body. The respiratory fingerprint may help fill in those gaps.

It's promising research, but the rocky history of fingerprints shows why good science is slow and cautious. The method of using fingerprints as identification was developed in 1892, and they became prime evidence for many convictions and executions. Now, in the era of DNA evidence, several people convicted based on their fingerprints have been exonerated.

A ground-breaking development in snakebite treatment has emerged from two small vials of blood. Specifically, the blood of Tim Friede, a Wisconsin man who has voluntarily injected himself with snake venom and let snakes bite him for the last two decades.

Most people would do anything to avoid a venomous snake bite. But Friede set up a lab in his basement to try and help in the field of antivenom research. He is not a scientist, nor was he affiliated with any research body. Snakes and their bites just piqued his curiosity.

Speaking to The New York Times, he explained that a garter snake bit him when he was five. This harmless interaction triggered his fascination with snakes. “If I only knew back then what was going to happen,” he laughed.

Early disaster

In 2000, he began exposing himself to venom. He started with scorpions but soon changed to snakes. A year later, he let two cobras bite him. It sent him into a coma, and he woke up four days later in a hospital. His wife was understandably incandescent with rage when she found out what he had done. But so was Friede, for different reasons: He could not believe he had not thought it through properly.

From that point, he started injecting himself with small doses of the venom to build up his immunity. Only then would he allow snakes to bite him. Over the years, he has injected himself with 650 doses of venom and endured more than 200 bites from some of the world's deadliest snakes.

Throughout this, he emailed multiple scientists to try to get them to study his blood. A few did sample it, but it never led anywhere. Then in 2017, he got a call from Jacob Glanville. An immunologist by trade, Glanville used to work on universal vaccines and wondered if he could apply the same logic to antivenoms. Rather than targeting the part of the venom that makes it unique, universal antivenom would act on the parts that are common to multiple venoms.

Can I have your blood, please?

When he read about Friede, he realized the potential. "If anybody in the world has developed these broadly neutralizing antibodies, it's going to be him," he thought, so he reached out. "The first call, I was like 'this might be awkward, but I'd love to get my hands on some of your blood',” Glanville told the BBC.

It was exactly what a delighted Friede had been waiting for.

“I’m really proud that I can do something in life for humanity, to make a difference for people that are 8,000 miles away, that I’m never going to meet, never going to talk to, never going to see,” he said.

Glanville and biochemist partner Peter Kwong collected two vials of Friede's blood. Their research focuses on elapids, the family of venomous snakes that includes mambas, cobras, taipans, and coral snakes.

They identified two antibodies capable of neutralizing a broad spectrum of snake venoms. They combined these with varespladib, a molecule that inhibits venom enzymes, then tested this combination on mice exposed to venom. Thirteen mice were fully immune, and the remaining six showed partial protection.

Don't try this at home

Conventional antivenoms come from the blood of horses or sheep that have been given a specific venom. Typically, they are expensive, have limited regional effectiveness, and may cause severe allergic reactions because the antibodies come from non-human mammals. In contrast, the new antivenom is lab-produced, potentially reducing costs and allergic risks, and offers broader protection.

While Friede's work is hugely significant, experts caution anyone against replicating his methods. The research team noted that all necessary antibodies have been identified, and no further self-exposure is needed.

This is just the first stage of research. Next, they hope to test their universal antivenom on dogs bitten by snakes at a veterinary clinic in Australia. They would then need to test on larger animals before moving on to humans.

My father always insisted on swimming in mountain tarns even in the depths of winter, which we all assumed meant there was something wrong with him. But health influencers have long touted the benefits of cold water plunges. The practice has been recommended for exercise recovery, increased energy levels, and even mental health disorders.

Curious about what cold plunges actually do to the human body, researchers at the University of Ottawa decided to take a closer look. The study reveals that after only a week of regular plunges, their subjects were seeing positive changes on a cellular level.

New evidence for an old practice

Humans seem to have an instinctual belief that getting really cold for a bit is good for us. Hippocrates recommended immersion in cold water for tetanus patients, and both the Roman physician Galen and Chinese surgeon Hua To favored an icy dip to treat fever.

In more modern times, the use of icy plunges expanded to all manner of ailments. English physician John Floyer published a treatise on temperature therapy in 1697. In it, he wrote that during summertime, "it is necessary to concente [sic] our Strength and Spirits by Cold bathing." By following his own regimen, he claimed to have made himself healthier and heartier.

During the 19th century, physicians used cold therapy to treat mental illness, numb limbs for amputation (this was before actual anesthesia), and lower fevers. The upper classes started cold bathing for all manner of aches and for that ephemeral and still sought-after "wellness."

Sea bathing became enormously popular as a general health and hygiene practice. One proponent was William Cullen, an 18th-century Scottish physician who prescribed cold showers (and cold enemas) for a range of ailments. The second thing did not catch on as much.

Throughout the 20th and 21st centuries, the popularity of cold water plunges has only increased. Sports medicine, especially, has embraced the practice for post-exercise and injury recovery. But just what exactly happens to a person when they undergo regular cold water treatment?

Cellular change

The Ottawa researchers, led by Glen Kenny and Kelli King, submerged their subjects in 14°C (57˚F) water for an hour a day, seven days in a row. By collecting blood samples before, during, and after this regimen, they could watch the effects of the plunges.

At first, it didn't look good. The stress on the body was significant, and it threw off the autophagic systems of the cells. Autophagy is the cell's cleanup and recycling system. When organelles are damaged or no longer needed, autophagic processes dispose of them. The material is then reused to make new cell parts. When this system isn't working well, damaged or unbalanced cells build up. This buildup of damaged cells is part of the aging process.

If cells are damaged, the body may trigger apoptosis, which destroys a cell entirely. Apoptosis is normal, and some cells simply need to go. However, it's much more efficient to repair them through autophagy rather than relying only on apoptosis. As the subjects' autophagy went down, apoptosis went up to compensate.

But after a few days, the patients' cells started to acclimate. Autophagy picked back up, though stress was still evident as well. By day four, the subjects were "over the hump," as it were. Their cells were undergoing autophagy more and apoptosis less.

Cold plunges for all?

The results are promising. By acclimating themselves to the cold, the subjects were better able to withstand the temperature extremes they were exposed to. More than that, Kelli King called cold water plunging a "tune-up for your body’s microscopic machinery." The positive impact on autophagy has implications for disease prevention and the slowing of aging.

But this was a small study. There were only 10 subjects, all healthy adult men. People of different ages and sexes handle cold differently. For people with preexisting conditions, this sort of treatment can be dangerous.

One influential cold-water health guru, a Dutch man named Wim Hof, has faced multiple accusations of negligence for his recommendations. A Sunday Times investigation in May of 2023 revealed 11 deaths connected with his teachings, which combine ice water plunges and breathing exercises.

The American Heart Association has come out against cold therapy. Sudden exposure to extreme cold can trigger heart attacks even in young, fit people. In fact, University of Portsmouth researcher Mike Tipton, an expert in the physical effects of cold water, found young and healthy people had up to a three percent chance of cardiac arrhythmia in an icy plunge.

The University of Ottawa subjects were carefully monitored and vetted. The amateur fitness enthusiasts trying cold plunges at home are not. So take this study as it is: fascinating preliminary research. Not a how-to guide for a frigid DIY fountain of youth.

In December, 40-year-old Max Armstrong went on a camping and hunting trip with friends. The trip had turned into a nightmare. A minor burn on Armstrong's thumb escalated to a double leg amputation.

Armstrong is an experienced outdoorsman. In 2016, he completed a 151-day trek from Mexico to Canada and treated dozens of minor cuts, scratches, and burns along the way. On his latest outing, he accidentally touched a hot skillet while cooking and burned his thumb slightly. Armstrong thought nothing of it, applied a bandage, and continued his activities.

Two days later, he noticed swelling in his left leg. At first, he assumed that it was just an ankle injury that he hadn't noticed and would improve in time. But the swelling intensified, his toenails turned purple, and the pain became unbearable. Realizing the severity of his condition, Armstrong went straight to the emergency room.

Induced coma

By the time he arrived, his eyes were rolling back in his head, and he was showing signs of confusion. He had sepsis. To try and control the worsening situation, doctors put him into an induced coma for six days.

Doctors diagnosed Armstrong with a severe infection caused by Group A Streptococcus bacteria, commonly known as strep A. This particular type was, unfortunately, the potentially deadly Invasive Group A Strep. It had entered his body through the burn on his thumb. This infection rapidly progressed to sepsis. While he was in a coma, the infection caused significant tissue damage, turning his feet black from necrosis.

After waking him up, the doctors told Armstrong and his family that there was a strong chance he would not make it due to the severity of the sepsis. They started mentioning amputations as a possibility to stop the infection from spreading up his legs. Initially, Armstrong was determined to keep his legs.

He told People magazine, “My mom was taking photos. And they [his feet] looked so black, and the veins were cooked. They just looked like they'd never be able to be used again.”

The necrosis was speeding up his legs, and he knew if it advanced any further, even a below-the-knee amputation would no longer be enough. At this point, he agreed to the amputation.

Hopes to hike again

On December 23, both legs were amputated. "Initially, when I woke up, I thought my legs were still there, and then I came to realize that they weren't."

By this time next year, he hopes to be hiking in the mountains again. For now, his dream is to walk around his home and take his dog for a walk.

Such outcomes are rare, but they underscore that severe freak infections from minor injuries are possible, so we need to seek medical attention promptly when small ailments behave strangely.

Professional road cycling has made huge leaps in curbing cheating since Lance Armstrong’s seven-year dominance of the Tour de France. But rabid cycling fans and insider pundits still harbor fears that cheating is still producing winning performances at the highest levels. The complete trust of the top riders and teams has been hard to come by. Any hint of foul play generates extreme scrutiny.

From barbituates, steroids, pain killers, EPO, blood transfusions, and motor doping, big-money cycling has exercised extreme measures to obtain the most marginal of competitive advantages. So when chatter surfaces about a new, high-tech, novel way to squeeze out a gain, it isn’t much of a surprise.

Last year, word spread that road cycling’s winningest riders and teams could inhale poisonous gas in the name of performance. This shocked even the most scrupulous fans.

But yesterday, the Union Cycliste Internationale (UCI) officially banned the potentially deadly practice of repeated carbon monoxide inhalation from all competitive cycling under its jurisdiction.

The official press release summarizes the ban as follows: “The new regulation forbids the possession, outside a medical facility, of commercially available CO re-breathing systems connected to oxygen and CO cylinders. This ban applies to all license-holders, teams, and/or bodies subject to the UCI Regulations and to anyone else who might possess such equipment on behalf of riders or teams.”

The new ruling goes into effect on February 10.

Carbon monoxide cheating: why cyclists do it

Carbon monoxide (CO) gas can be an invisible, silent killer. This is why we have CO detectors in RVs and homes. CO has a stronger affinity to the oxygen-carrying component in red blood cells (hemoglobin, or Hb) than oxygen itself.

When inhaled, CO displaces oxygen and eventually causes “suffocation” from the inside. We need detectors because the gas has no taste, color, or odor.

Ironically, CO’s strong affinity for Hb can potentially also enhance aerobic performance. Anything that reduces the blood’s oxygen level over time will stimulate a compensatory response to reestablish this capacity. This is why athletes go to altitude.

The lower partial pressure of oxygen at higher elevations results in fewer oxygen molecules bound to red blood cells. This also means the blood transfers less oxygen to working muscles.

As the athlete continues to live and work at altitude, the body produces more blood volume, hemoglobin, and other factors to compensate. Theoretically, this boosted oxygen-carrying ability provides a greater advantage at lower altitudes.

Repeatedly inhaling CO has the same oxygen-lowering effect as high altitude but with a different mechanism. Instead of less air pressure driving less oxygen into the blood and tissues, CO competes with the oxygen for binding sites on the Hb of red blood cells. Less oxygen bound to Hb ultimately means less oxygen for working muscles.

Studies strongly suggest that it triggers the same compensatory adaptations. But, unlike altitude training, CO inhalation can be extremely harmful.

How are cyclists doing it?

The practice of CO “doping” actually stems from a diagnostic test that teams used to determine training efficacy. Specifically, CO “rebreathing” helped determine blood volume and Hb mass, which helped teams quantify physiological gains made during altitude training camps.

It worked like this: Athletes determine a baseline measurement for CO blood levels using blood and breathing tests. Then, the athlete inhales a small amount of CO diluted with oxygen for two minutes through an enclosed circuit. The CO binds to Hb in the red blood cells to form carboxyhemoglobin.

After these two minutes, teams measured the amount of carboxyhemoglobin in the breath and blood and compared it to the baseline levels to calculate Hb mass. This Hb mass is an indicator of the effectiveness of altitude training or any other method used to increase the oxygen-carrying capacity of blood.

CO rebreathing machines specific to this type of testing automate this procedure. However, athletes can achieve the same results through a manual process using a closed-circuit carbon monoxide rebreather system.

Cheating by inhaling carbon monoxide

What happens next?

This article first appeared on GearJunkie.

New research has shown that the low oxygen levels that accompany high-altitude sports impact the quality of sperm and decrease male fertility.

The study addresses the serious decline in male fertility over the last five decades. Since the 1970s, sperm counts have dropped by 50%, and there is no sign of that slowing down.

Several studies have shown how a lack of oxygen reaching the testicles threatens reproductive health. Medically, men are considered infertile if, after 12 months of regular unprotected sex, no pregnancy occurs. Those with low fertility have less chance of conceiving. Both infertility and low fertility have increased dramatically in recent years.

Medical conditions such as sleep apnea, testicular torsion, and varicocele seem to be the leading causes. Varicocele (enlarged veins in the scrotum) accounts for 45% of infertility in men. Meanwhile, between 13% and 30% of men suffer from sleep apnea.

High-altitude hiking and climbing have a much shorter effect on sperm. However, there is still a risk.

Low oxygen levels may not cause permanent infertility, but they do lead to a low sperm count, decreased sperm quality, and disruptions in hormone production. Tessa Lord, who led the study, commented, “The effects on fertility are short-term but can still take a few months to resolve after returning to sea level.”

The long-term effects of oxygen deprivation are still unknown. But according to recent evidence, Lord suggests that"testis hypoxia in fathers could result in embryos with developmental issues, and those children could grow up to experience fertility issues themselves."

On average, snakes bite 1.8 million people worldwide each year, and 138,000 of those are fatal. Researchers have now found a new treatment for at least cobra bites -- a common blood thinner called heparinoids.

If a venomous snake bites you, getting antivenom as quickly as possible is crucial. Unfortunately, not all venoms — including venom from several cobra species — have effective antivenom. Cobras may not be the deadliest snakes in the world, but their venom can still cause serious tissue damage.

Most antivenoms are specific to either one or a few species of snake. They are expensive, have a limited shelf life, need refrigeration, and must be administered in a hospital. However, most snakebites occur in remote areas, where medical treatment is not easily accessible. Also, though antivenoms save lives, they do not limit the tissue damage around the site of the bite. The necrosis is often so severe that it leads to amputations.

Decoying away the venom

Scientists from the UK, Australia, Canada, and Costa Rica set out to find more treatment options for snakebites. Typically, research focuses only on a few of the quickest-acting and deadliest venoms.

“It’s a neglected area….It seems like if it’s not immediately fatal, it’s not the main focus,” Shirin Ahmadi, a specialist in skin cell death who did not participate in the study, told Science.org.

The team decided to start with cobras and picked one whose venom causes tissue damage. Using venom from African spitting cobras and CRISPR gene-editing technology, they identified the genes affected by cobra venom and which trigger necrosis. Those genes involved in producing heparan sulfate -- common sugars in cell membranes -- seem to be central to the tissue damage. Toxins from the venom bind to these sugars, damaging the cells and tissues.

When the research team saw this, they had a brain wave. If they could find a molecule similar to heparan sulfate, it might act as a decoy. This is where heparinoids and heparin come into play. When cells are flooded with blood thinners, the toxins bind to them instead of to the sugars in cell membranes. This stops the toxins from harming cells and necrosis from developing. Lab tests confirmed this worked in both human cells and in mice.

This is a huge leap forward in treating snakebites. As these drugs are already approved and readily available, moving to clinical trials will be a speedy process. In the long term, scientists hope to create an epi-pen device that rural people at high risk of cobra bites can carry.

“Our discovery could drastically reduce the terrible injuries from necrosis caused by cobra bites," co-author Greg Neely told The Independent. "It might also slow the venom, which could improve survival rates.”

In recent decades, the vulture population in India has collapsed. Since the mid-1990s, populations of several species of the big carrion-eating birds have decreased by up to 99.9%. A study reveals that this has severely impacted human health in the region.

When vultures feed on the remains of dead animals, they remove these rotting carcasses from the ecosystem, including any diseases those animals were carrying.

The vulture populations started rapidly declining because of diclofenac, a drug widely given to livestock for pain and inflammation. It happened to be toxic to vultures and killed them when they fed on the carcasses of livestock that had ingested the chemical.

Why vultures are so important

India has over 500 million head of cattle. Until recently, vultures have been one of the main ways to get rid of the dead ones. With the vultures in decline, the carcasses started to build up, spreading pathogens.

The build-up of carcasses outside tanneries, in particular, got so bad that the government ordered them to use chemicals to get rid of the remains. These chemicals found their way into nearby waterways. Elsewhere, farmers threw carcasses into nearby rivers, likewise contaminating water supplies.

The available carcasses also meant that the number of stray dogs began skyrocketing. These dogs often carried rabies, and more humans were bitten and infected.

The study compared the death rates of humans in all districts where vultures were once prevalent. Researchers used data from before and after the use of diclofenac in 1994. The human death rate increased by an average of 4% after the vultures started dying out. This added up to over 500,000 human deaths between 2000 and 2005.

Though some species of vultures are now near extinction in India, conservation efforts are minimal compared to other species around the world. The birds are constantly associated with death, are not cute and cuddly, and so are not good candidates for fundraising initiatives.

Some primates have learned to use rudimentary medicine. In May, researchers observed orangutans chewing up medicinal leaves and then applying the juice to wounds on their skin. Now, a team in Uganda has observed chimpanzees using 13 different therapeutic plants to self-medicate.

Following sick chimps

The team of researchers observed two groups of chimpanzees in Uganda, looking for sick or injured individuals.

Of 170 chimps within the groups, 51 suffered from diarrhea, parasites, or wounds. The team began following the sick apes for 10 hours per day. The sick primates often appeared to be searching for a specific plant to eat. These plants were not part of their usual diet, such as tree bark or the skin of a certain fruit.

The researchers then took samples from the plants to test their healing properties. The vast majority of them were antibacterial.

"We were looking for these behavioral clues that the plants might be medicinal," Elodie Freymann, lead author of the study, told the BBC.

In total, they collected 17 samples from 13 plant species. Ninety percent of them stopped bacterial growth, and a third also acted as an anti-inflammatory.

Speedy recovery

Incredibly, the chimpanzees could select the plant that would help their specific injury or illness. All the ill chimps made speedy recoveries.

The team admitted they couldn't prove the plants they ate caused the recoveries, but the study makes a compelling argument about these chimpanzee's ability to speed up their healing process. Many of the plants the sick chimps chose to eat hold very little nutritional value, and no healthy chimpanzees were eating them.

Some interesting examples include a male chimp with a hurt hand that he could not use. While other chimps were eating, this chimp searched for a specific fern that the rest of the group did not consume. A few days later, the chimp's hand was fine again.

Another chimp suffered from diarrhea and tapeworms. With two companions, it left its group and searched for an Alstonia boonei tree. The chimp chewed on dead bark from the tree and swiftly recovered.

Inter-species learning

A huge takeaway from this study is how much we can learn from the medicinal knowledge of other species.

"Chimpanzees are incredibly smart, and it makes perfect sense they would have figured out which plants can help them when ill or injured," Freymann told the Washington Post.

Plants are important in creating new drugs, but finding medicinal plants is incredibly difficult. The research team's study proves how crucial it is that we "prioritize the preservation of our wild forest pharmacies, as well as our primate cousins who inhabit them."

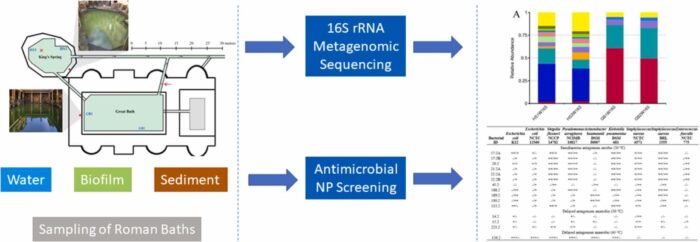

New research conducted at the site of the Roman baths in Bath, England, seems to back up the long-held belief that the waters there could do more than relieve achy joints and promote relaxation. They might legitimately hold healing properties.

In the journal The Microbe, researchers from the University of Plymouth’s School of Biomedical Sciences revealed that at least 15 of the microorganisms swimming in Bath's world-famous waters produce antimicrobial compounds that could help combat some of humanity's most vicious microscopic enemies: E.coli, Staphylococcus aureus and Shigella flexneri, to name three of the most prominent.

"This is a really important and very exciting piece of research," Dr. Lee Hutt, Lecturer in Biomedical Sciences at the University of Plymouth and lead author on the paper, told ScienceDaily. "The waters of the Roman Baths have long been regarded for their medicinal properties...Now, thanks to advances in modern science, we might be on the verge of discovering the Romans and others since were right."

Science meets tradition

Everyone -- including animals from capybaras to snow monkeys -- enjoys a hot spring, but no one loved to get their soak on better than the ancient Romans. The Romans started dipping in Bath sometime between 60 and 70 AD, though native Britons almost certainly used the springs long before the invaders arrived.

Regular soaking continued until the Roman Empire withdrew from Britain in the fifth century AD. The Romans who stayed around (not to mention Romanized Britons) kept up the practice for a while, though the facilities were in ruins by the sixth century, according to a chronicle penned during the reign of Alfred the Great, another couple of centuries down the road.

Soaking enthusiasts in the early and late Middle Ages rebuilt the site, and the waters of Bath have been a tourist attraction ever since, renowned for their healing abilities. Until now, those legends have been purely anecdotal.

Enter the scientific method. Scientists collected biofilm, water, and sediment from two locations in the baths. They then analyzed the samples using gene sequencing technology and tried-and-true culturing methods. The scientists isolated 300 types of bacteria from the samples, 15 of which packed enough antimicrobial punch to warrant further study.

More work to do

The team stressed that more work is necessary before the organisms at Bath can be used to combat the estimated 1.25 million deaths that occur annually due to antibiotic-resistant bacteria. However, the initial study was promising enough that the University of Plymouth will expand the research beginning this fall.

So the next time someone tells you a hot spring may have healing properties, don't immediately roll your eyes. Do the smart thing and make like a macaque.

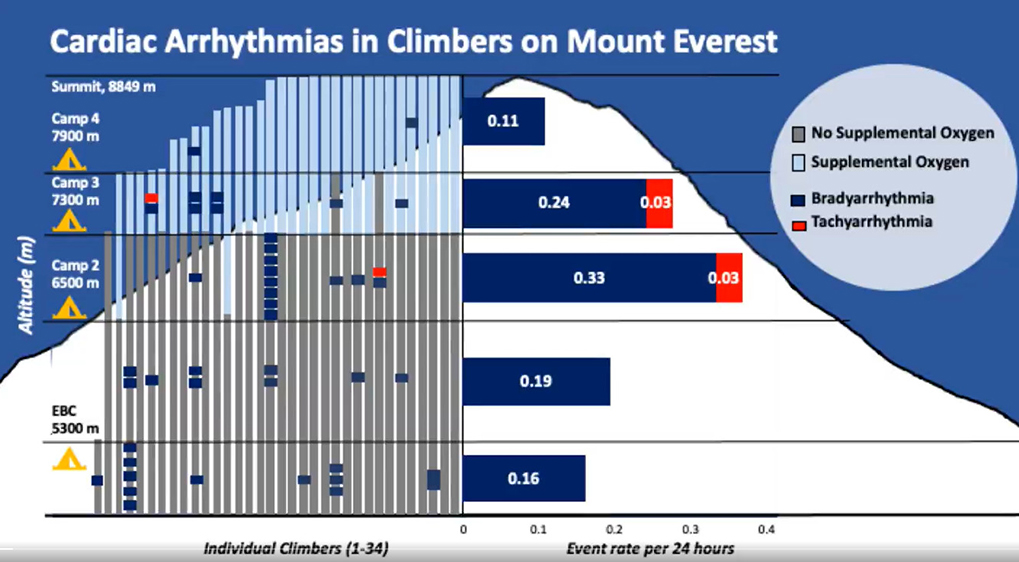

As the Everest summits begin, climbers must be aware of an extra concern besides the thin air and the effort: their heart condition. Climber and cardiologist Thomas Pilgrim headed a recent study that showed one-third of Everest climbers suffer cardiac arrhythmia (irregular heartbeat) during their ascent.

13 of 41 climbers had arrhythmias

The SUMMIT study took place during the spring of 2023 and involved 41 volunteers, all supposedly healthy. Fourteen of them eventually summited, while the others retreated at some point on the South Col route. There were 45 arrhythmias over 13 individuals. None of these arrhythmias showed obvious symptoms.

Researchers took various cardiac measurements of the 41 climbers and did an exercise stress test before the expedition. They recorded continuous heart rhythm measurements before and during the expedition.

While the proportion of climbers with arrhythmia remained stable as the altitude increased, the number of events per 24 hours increased with altitude between Base Camp and Camp 3 (at 7,000m). The event rate then decreased. Roughly 80% of the arrhythmias occurred in climbers with no supplementary oxygen.

"Many of the volunteers were sherpa climbers, which gave the study an extra benefit," Pilgrim told ExplorersWeb in a Zoom interview from Switzerland. "After all, they are the people who spend the most time on the mountains and are the most exposed to altitude."

No clear diagnosis

Pilgrim noted that when people die on Everest from something other than an accident, there is often no clear diagnosis. It can be unclear if such deaths, usually attributed to Acute Mountain Sickness (AMS), were preventable. So one of the key aims of the study was to learn whether arrhythmias were partly to blame.

All participants had previous experience at altitude.

"This is probably a selection bias, but people who don't tolerate the altitude would hardly make it to the summit of Everest and probably have the most arrhythmias," Pilgrim said. "So what we had in the end was a selection of healthy people [who were] already acclimatized."

Pilgrim climbed Everest himself and participated in the study. He eventually retreated near the South Col, without summiting. He suffered no arrhythmias during his climb.

Asked whether the sherpa guides, who are exposed to altitude most of the year, could end up with arrhythmias from the chronic stress, Pilgrim said the study is too small for such a conclusion. However, the current study suggests no such relationship. Some participants had summited 10 8,000m peaks and didn't fare any worse than others.

"Perhaps there is a genetic predisposition to arrhythmias," Pilgrim said.

Bearing in mind the limitations of such a small sample, the project did contradict a previous study that suggested sherpas are immune to arrhythmias. "They can have the same cardiac issues as anyone else," Pilgrim explained.

How to tell arrhythmia from fatigue

Another question is whether the arrhythmias were from the altitude or simply the result of strenuous effort, such as an Ironman triathlete might experience at sea level.

"There are differences," Pilgrim said. "At high altitudes, you have characteristic breathing patterns. For instance, periodic breathing (apnea) during sleep creates conflict between the sympathetic and parasympathetic nerve systems and increases the risk of developing bradycardia. Also, in these hypoxic environments, you tend to hyperventilate and that causes electrolyte disturbances, which can lead to tachycardia."

Another interesting finding is that the arrhythmias stop the moment the climber descends. It's not permanent damage. Equally, the use of supplemental oxygen radically diminishes the risk of arrhythmias.

Prevention tips

"Have a thorough cardiac checkup before going to the mountains and consider using supplemental oxygen," Pilgrim recommends.

It is worth noting that some arrhythmias are more dangerous than others. "The most concerning is the tachyarrhythmias [the heart beats too fast]. Those were the least registered during the study," Pilgrim said.

He suggests that further studies could explore whether some medications might change the electrical conduction of the heart that controls its beating. "We need to research if and how an unfortunate combination of medication and altitude could lead to a cardiac episode."

But how can you tell tachycardia from fatigue?

"It is very hard...unless someone is monitoring you," Pilgrim said. "There are so many dangers up there that most climbers consider cardiac arrhythmias the least of their problems. In the future, technology should permit people to monitor climbers from Base Camp."

The SUMMIT project is just a first step. Further studies should follow.

Further studies

"It will be interesting to identify individuals who may develop potentially dangerous arrhythmias. And then to find how to minimize the chance of developing them."

Hopefully, future studies will tackle important safety questions for high-altitude mountaineering. In particular, since modern logistics allow for much larger and faster expeditions, it would be interesting to know if the rushed pace of expeditions increases arrhythmias. Pilgrim agrees that this needs further research. "But I think there might be a correlation," he ventured.

You can read the SUMMIT study here.

Dr. Thomas Pilgrim is a cardiologist and associate professor at Bern University Hospital. While his specialty is valvular heart disease, his collaboration with Nepalese colleagues led to research on high altitude-induced heart disease. "I have a particular interest because I am a climber myself, a Cho Oyu summiter, and I attempted Everest last year," he says.

For the first time, an animal has been observed treating a wound with medicinal plants.

Biologists in Indonesia noticed Rakus, a male Sumatran orangutan living in Gunung Leuser National Park, behaving oddly in June 2022. Rakus was making “long calls,” an orangutan vocalization generally understood to signal conflict between males. He also had a large lesion below his right eye.

In this month's Scientific Reports, a multi-disciplinary team links the wound to the potential fracas — and then describes a never-before-seen event.

Monkey medicine

Shortly after he sustained the injury, Rakus started “selectively” ripping leaves off a certain medicinal tree, chewing them, and applying the juice to the raw area.

The ape had selected Akar Kuning (Fibraurea tinctoria), which locals use to treat diabetes and malaria.

“As a last step, he fully covered the wound with the chewed leaves,” the study noted.

It took several minutes. Five days later, the wound was closed. Within a month, it had fully healed.

Various factors indicated that Rakus’ behavior was intentional. It took a long time to apply the salve, and the ape rested almost twice as long as usual in the days after he applied it.

However, he might have accidentally discovered the treatment, said lead study author Isabella Laurmer of the Max Planck Institute in Germany.

Orangutans also eat Akar Kuning. It’s possible Rakus touched the wound while feeding and noticed its pain-relieving effects — then, understandably, kept going.

'Socialized' healthcare?

He also might have picked up on the technique from his neighbors, Laurmer said. Even though it’s the first time anyone has witnessed an animal treating a wound medicinally, the behavior could exist elsewhere. African and Asian great apes are known to actively treat wounds, although in different ways. One method involving insects, in particular, grabbed researchers' attention and suggested cultural behavior.

“[This] provides new insights into the existence of self-medication in our closest relatives and in the evolutionary origins of wound medication more broadly,” the paper suggested. “It is possible that there exists a common underlying mechanism for the recognition and application of substances with medical or functional properties to wounds, and that our last common ancestor already showed similar forms of ointment behavior.”

Every season since 2003, there is a team at Everest Base Camp whose members are not hoping to reach the summit. They are the volunteer doctors at the Everest ER clinic. While not often mentioned in climbers' Instagram posts, they carry out remarkable work for everyone, but most of all for local workers.

"We treat anyone who needs our medical services," Dr. Sanjeeb Bhandari, co-medical director of the Everest ER clinic and assistant medical director of the Himalayan Rescue Association, told ExplorersWeb. "The team provides medical services to Nepali people for free and charge client climbers for consultation and medicine."

Bhandari added: "Every year we see 450 to 650 patients. Most of them have upper respiratory tract infections along with AMS (acute mountain sickness), HAPE (high altitude pulmonary edema), HACE (high altitude cerebral edema), frostbite, and a few traumas with broken bones."

The HRA began in 1978, with a small aid post in Pheriche. The Everest ER clinic at Base Camp) launched in 2003. By 2011, Nepalese physicians were also volunteering for the clinic.

"The Everest ER started with a small tent with basic medical supplies. [Now we have] a bigger tent with ECG and ultrasound capabilities," Bhandari said. "We leveled up with the evolution and the availability of helicopter rescue. Initially, patients needing rescue used to be carried down on someone's back, on a stretcher, or on a horse to the Pheriche aid post. Now helicopters carry out most of the rescues, taking patients to Lukla, if not to Kathmandu."

This year, the clinic counts on the leadership of Dr. Gregory Stiller of the U.S. and Nepalese MBBS Shreyasi Karki and Nishant Joshi. The team also includes long-line rescue specialist Lakpa Norbu Sherpa. The staff is currently in Pheriche, where they have already attended to some patients, mostly suffering from AMS.

Why volunteer?

ExplorersWeb spoke with Dr. Joshi, currently in Pheriche but on his way to Everest ER later this week. Joshi worked at the Pheriche aid post and Gosaikunda Lake last year. This year will be his first experience at the Base Camp clinic.

"Working at altitude exposes you to various pathologies you would never see normally," he said about his voluntary work. "It also exposes you to the daily hardships people deal with here. It is an eye-opening experience."

Last season, there were more than 50 patients with HAPE, the highest since the clinic opened 50 years ago. Almost 45 of them were Nepalese guides and porters, Joshi pointed out.

He noted that charging six insured trekkers (who usually have the money refunded by their insurance companies) is enough to pay for the treatment of all 45 guides and porters.

"It is a rewarding experience to be able to help just for the sake of helping," Joshi said.

He remembers a sherpa lady who asked for his name to dedicate prayers to him at the monastery.

"Nowhere in the world would I have such a healthy doctor-patient relationship as this. That experience made me want to come back."

Joshi explained that the doctors devote most of their work to local people. Locals are already over-exerted by hard work and are therefore the most vulnerable.

"I did a lot of night shifts looking after patients who would be carried to us at midnight from higher altitudes. When I provide medication and consultations, I would find myself sitting and staring at the stars and mountains reflecting moonlight, grateful that I could help someone who would have died had someone not volunteered in a place like this."

Growing beyond Everest

In addition to the field hospital at EBC, the Himalayan Rescue Association (HRA) runs aid posts on two of the most popular trekking routes in Nepal. There is one post in Pheriche, on the way to Everest Base Camp, and another in Manang town, in the Annapurna region.

"In August, we also run a temporary health camp at 4,200m Gosainkunda Lake (Langtang) when it receives 20,000 pilgrims over four days. Most of them are Nepalese nationals with little to no knowledge about high-altitude illnesses."

As a non-profit, the HRA depends on donations. These come largely from individuals, with a little from Nepal's government. Should their budget increase in the future, they would expand their work to other Base Camps, especially the very popular Manaslu during fall season.

Field workers attend to medical emergencies but they are aware that prevention is much better than curing sickness. That is why they also run educational training in their Kathmandu office for teams preparing for an expedition.

"From a medical prevention perspective, educating the climbers is key," the HRA staff explain. "Frequency of illness has decreased because of preventative efforts by us to educate the climbers and the Everest Base Camp community."

The health front line

The staff at the aid post and the Everest ER clinic are mainly busy with emergencies. However, as the first line of medical assistance, they are aware of the array of health problems faced by men and women who work at high altitude, not only during the season but throughout their lives.

"There are many chronic medical issues we deal with every day at the clinic: gastritis, heart issues, hypertension, diabetes, etc. For many issues we direct them to centers that specialize in the appropriate care," Joshi said.

The clinic also covers mental health issues. "We receive panic attacks, conversion disorder, and patients with depression. We counsel, appropriately assess the severity of the symptoms, and treat or refer them accordingly," Joshi said.

In a few weeks, we will check in with Dr. Joshi for an update on the medical situation at Everest Base Camp.

BY STUART AINSWORTH AND CAMILLE ABADA

If you're bitten by a venomous snake, the medicine you need is antivenom. Unfortunately, antivenoms are species specific, meaning you need to have the right antivenom for the snake that bit you. Most of the time, people have no idea what species of snake has bitten them. And for some snakes, antivenoms are simply not available.

New research my colleagues and I conducted provides a significant step forward in enabling the development of an antivenom that will neutralize the effects of venom from any venomous snake: a so-called "universal antivenom."

In our paper, published in Science Translational Medicine, we describe the discovery and development of a laboratory-made antibody that can neutralize a neurotoxin (a toxin that acts on the nervous system) found in the venom of many types of snake around the world.

Most victims are children and farmers

Venomous snakes kill as many as 138,000 people each year, with many more survivors suffering from life-changing injuries and mental trauma. Children and farmers make up the bulk of the victims.

The active ingredients in antivenoms are anti-toxin antibodies. They are made by injecting horses with small quantities of snake venom and harvesting the antibodies. This method of making antivenom has remained the same for over a century –- and it has substantial drawbacks.

In addition to antivenoms being species specific, they are also not very potent, so you need lots of antivenom to neutralize the venom from a bite.

Also, because antivenoms are made in horses, you are highly likely to experience severe side-effects when administered, as your body's immune system will detect and react to the foreign horse antibodies circulating in your bloodstream.

Antibodies that are made in the laboratory using genetically modified cells are routinely used in humans to treat cancers and immune disorders. A long-held hope is that the technology used to produce these antibodies can be used to make antivenom and eventually replace traditional antivenoms, thereby solving many of the issues current antivenoms face.

The antibodies in lab-made antivenoms could be "humanized," a process that tricks your immune system into thinking foreign antibodies are your own antibodies. This might reduce the rate of severe side-effects that are commonly encountered with horse-derived antivenoms.

Paralysis and death avoided

One of the most important families of toxins in snake venoms are neurotoxins.

These toxins prevent nerve signals from traveling from your brain to your muscles, paralyzing them. This includes paralyzing the muscles that inflate and deflate your lungs, so prey and human victims quickly stop breathing and die.

These neurotoxins are in the venoms of some of the world's most deadly snakes, including the African black mamba, the Asian monocled cobra and king cobra, and the deadly kraits of the Indian subcontinent.

In our research, we describe the discovery and development of a lab-made humanized antibody that can neutralize key venom neurotoxins from diverse snakes from diverse regions.

100% success with mice

The lab-made antibody is called 95Mat5 and was discovered after examining 50 billion unique antibodies to find ones capable of not only recognizing the neurotoxin in the venoms of many species but also able to neutralize its deadly effects.

When injected into mice that had received lethal doses of venom, 95Mat5 was able to prevent paralysis and death in all the venoms tested.

These results are particularly exciting as they show that generating lab-made antibodies that can broadly neutralize the effects of venoms from many species is feasible, making the development of a universal antivenom a realistic prospect.

However, 95Mat5 is a single antibody that only works against neurotoxins. As we said earlier, to make a universal antivenom you will require a handful of antibodies. This is because snake venoms don't just consist of neurotoxins.

Next: Haemotoxins

Some snake venoms have haemotoxins, which make you bleed, and some have cytotoxins, which destroy skin and bone. To create a universal antivenom, capable of treating any bite from any snake, we still need to identify additional antibodies that can broadly and potently neutralize the other toxin types, in the same manner as 95Mat5.

We hope that once identified, these antibodies can be mixed with 95Mat5 to make an antivenom that is capable of neutralizing the venom of any snake, no matter what toxin types it possesses.

The requirement for antibodies for other venom toxins and also the need to ensure any new lab-made antivenom for effectiveness and safety in human trials means it will still take many years for a universal antivenom to become available to snakebite victims.

Other hurdles need to be overcome. These new antivenoms will probably need to be stored in a fridge to prevent loss of effectiveness, so it will need to be shown that they can be distributed in often warm regions of the world that don't have reliable electricity for refrigeration.

Lab-made antibodies are some of the most expensive drugs on the planet. While we are hopeful, it remains to be seen if lab-made antivenoms will be affordable for most snakebite victims, who are usually some of the poorest people in the world.

This article first appeared in The Conversation.

Today, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) announced a new injection treatment for severe frostbite. Approved for adults, Aurlumyn (iloprost) can reduce the risk of amputation following frostbite, officials say.

“This approval provides patients with the first-ever treatment option for severe frostbite,” said Norman Stockbridge, M.D., Ph.D., director of the Division of Cardiology and Nephrology in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. “Having this new option provides physicians with a tool that will help prevent the life-changing amputation of one’s frostbitten fingers or toes.”

Today, we approved an injection to treat severe frostbite in adults to reduce the risk of finger or toe amputation. https://t.co/LBJKSCBbl7

This approval provides patients with the first-ever treatment option for severe frostbite. pic.twitter.com/hPszLI6O9U

— U.S. FDA (@US_FDA) February 14, 2024

Severe frostbite is the deepest stage of tissue damage from prolonged exposure to extreme cold. It's characterized by loss of touch and temperature sensation. The tissue turns black before blistering badly.

While tissue regeneration from severe frostbite was previously possible with “optimal” medical treatment, according to the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH), injury reversibility was limited.

But the FDA’s case studies on iloprost, which opens blood vessels to prevent clots, were promising. The agency placed 47 adults with severe frostbite into three groups. “Group 1” received iloprost intravenously for six hours daily, for up to eight days. The two other groups received other treatments unapproved for frostbite, given with iloprost (Group 2) or without iloprost (Group 3).

No amputations needed

Bone scans followed, to predict the need for amputation. Zero out of 16 patients in Group 1 needed amputation. Group 2, the patients with iloprost along with the unapproved medications, fared better than Group 3.

Follow-up appointments proved consistent with the initial bone scan results, the FDA said.

The most common side effects of Aurlumyn include headache, flushing, heart palpitations, fast heart rate, nausea, vomiting, dizziness, and hypotension (low blood pressure), according to the FDA.

Actelion Pharmaceuticals US, Inc. earned the approval. The Johnson & Johnson subsidiary specializes in treating pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH), according to its website, and markets several drugs approved for that use.

Alchemy -- the pseudo-science of turning base metals into gold, finding a cure-all elixir, or a potion for eternal youth -- obsessed many pre-chemists of the Middle Ages. But not only men pursued these mysteries. Female alchemists became some of history’s earliest scientists. While chasing alchemy's occult will o' the wisp, they found cures to common ailments and designed apparatus that is still used in laboratories today.

Why did women gravitate toward alchemy?

Alchemy attempted to transmute ordinary metals like nickel and copper into valuable ones like gold and silver. However, its overarching goal was to attain perfection. Something called the philosopher's stone was the magical key to this pursuits.

Women explored alchemy via medicine, cosmetics, "kitchen chemistry," and religion, according to Sajed Chowdhury of Leiden University. They developed medicine and ways to better care for their families. They invented distillers to create ointments, fragrances, and other concoctions. It was alchemy in a domestic setting.

Alchemy carried an air of secrecy and mystery. "Secrets were a form of currency," according to one author, by which one could acquire power and influence.

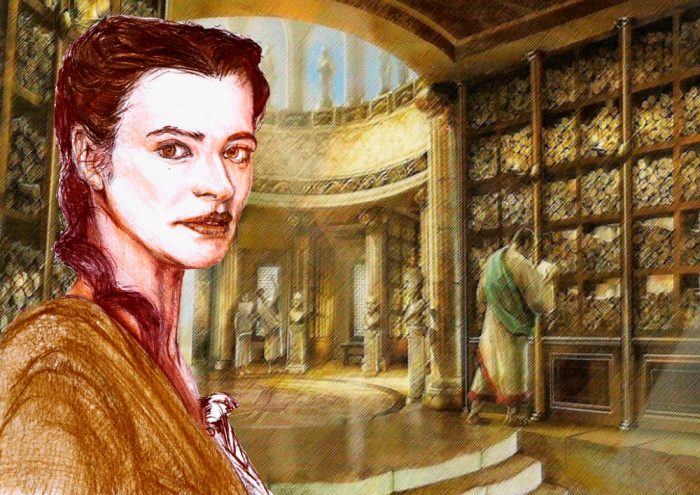

Nor was it just a medieval art. In the ancient world, perhaps the most notable female alchemists were Cleopatra the Alchemist, Mary the Jewess, and Hypatia.

Cleopatra the Alchemist

This Cleopatra was born in the 3rd century AD, 300 years after her more famous namesake died. Not much is know about her except that she lusted after gold, pursuing alchemy in the hope of amassing wealth.

Her single surviving text, the Chrysopoeia of Cleopatra, continues to baffle historians. It contains a series of cryptic symbols with very little context, including a snake devouring its own tail.

Historians believe that Cleopatra the Alchemist could have been a pseudonym or even a group of alchemists. In ancient Egypt, only the nobility practiced alchemy, suggesting that Cleopatra came from the upper echelons of society.

Whatever her identity, Cleopatra the Alchemist may have left behind a valuable apparatus called the alembic. This instrument consists of two vessels connected via a tube to distill liquids. It is still in use today, with modern modifications. However, some sources attribute the invention to Mary the Jewess or another alchemist.

Mary the Jewess

Mary the Jewess also lived around the third century AD. Her male contemporaries referred to her as Moses' Daughter or Mary the Prophetess, although there is no record that she was even Jewish. Her background is a total mystery, except that she is credited as the first Western alchemist. She appears in the writings of other alchemical figures, like Zosimos of Panopolis, who describes her as a wise sage.

Mary specialized in creating laboratory equipment, new techniques, and new substances. She managed to produce silver sulfide and possibly discovered hydrochloric acid. She is credited with inventing the tribikos, another distilling apparatus. Additionally, she created the kerotakis, which collected vapors, and the water bath, sometimes called Maria's Bath or bain-Marie -- essentially a double boiler.

Hypatia

Around 350 AD, Hypatia lived, studied, and taught in Alexandria. The daughter of a mathematician and scholar, she took up teaching to people of all faiths.

A brilliant mathematician and inventor, she invented instruments for astronomy as well as alchemical apparatus like the hydrometer, which measured the density of liquids.

Isabella Cortese

Isabella Cortese published The Secrets of Lady Isabella Cortese in the mid-1500s. In it, she describes herself as a learned and well-traveled woman who has mastered alchemy.

Her book was popular with both sexes. Even Queen Elizabeth I took her advice on beauty and anti-aging techniques. She provided recipes for creating the philosopher’s stone, for dying one’s hair, detoxing, and even curing erectile dysfunction.

One example is a recipe for "face color" which calls for white-feathered pigeons, bread soaked in goat's milk, silver, and gold.

Caterina Sforza

Caterina Sforza, the Countess of Forlí, had an affinity for cosmetics and medicine. She was highly educated in Latin and the classics. She had her own special herb garden for her experiments from which she produced fine fragrances and skin-lightening creams. Her manuscript Experimenti contained over 450 recipes for hair bleaching, treatment of wounds, and cures for fevers.

Unlike some women of the time, she did not hide her alchemical pursuits. Rather, her power and influence through a strategic marriage and political shrewdness added to the reputation of her alchemy skills.

Christina, Girl King of Sweden

Alchemy even enthralled royalty. Christina, the "Girl King" of Sweden, took an interest after meeting alchemist Johannes Franck. She examined the work of the Rosicrucians, an esoteric intellectual movement that combined metaphysics, mysticism, Christianity, and Hermeticism.

She hoped that Stockholm would one day become a center for learning, a sort of "Athens of the North."

The headliners of this year’s Ig Nobel science awards read like the itinerary of a Japanese game show.

Eating with electric chopsticks. Reanimated dead spiders. An “analyzing” toilet.

These experimental developments and more earned 2023’s “Ig Nobel” Prizes, awarded in a webcast Sept. 14 ceremony. In a reflection of the event’s punny name, the journal Nature has called the Ig Nobel Awards “arguably the highlight of the scientific calendar.”

It was the "33rd First Annual" rendition of the event that showcases “achievements that first make people LAUGH, then make them THINK.”

We've highlighted our favorite Ig Nobel expositions below.

‘Augmented gustation using electricity,’ Meiji University, Kanagawa, Japan

How much of the act of participating in a study group relies on the willingness to perform self harm in the pursuit of knowledge?

If eating with electrified utensils sounds like an episode in this sordid and deeply entrenched phenomenon, I’ve got news for you: It’s not.

Instead, two researchers from Japan’s Meiji University just wanted to find out an alternative channel to stimulate human “gustation” — or taste.

“Electric taste is the sensation elicited upon stimulating the tongue with electric current. We used this phenomenon to convey information that humans cannot perceive with their tongue,” the researchers assert in their paper.

The study first “proposes systems” to create electrically charged straws and chopsticks (which seems like the easy part if you’ve ever put a nine-volt battery on your tongue), then “discusses augmented gustation using various sensors.”

Bon appetit — or as we say in Japanese, Itadakimasu.

Turning dead spiders into robots, Rice University, Texas, U.S.

Scientists have consistently scrutinized natural structures with one key question: Can we engineer it better?

Acknowledging that “designs perfected through evolution” have inspired robots that mimic animals like cheetahs and jellyfish, this paper from researchers at Texas’ Rice University takes the next logical step.

“Incorporating living materials directly into engineered systems” is the slant. Dead spiders are the specimens.

Because spiders’ legs operate hydraulically, rather than muscularly, they can essentially be re-animated with fluids after death. The result is a mechanical "claw" or gripper that can lift 130% of its own mass.

“Furthermore, the gripper can serve as a handheld device and camouflages in outdoor environments,” the paper notes.

Zombies? Cyborgs? The next trend in handheld devices? No matter what, it’s got eight hydraulic legs. But you will need an ongoing supply of spiders, because each one "breaks down after 1,000 open and close cycles," the narrator helpfully explains.

‘A mountable toilet system for personalized health monitoring via the analysis of excreta,’ Stanford University, Calif., U.S.

A self-contained "smart" toilet “operates autonomously” and uses pressure and motion sensors to scrutinize biological wastes.

“[We use] easily deployable hardware and software for the long-term analysis of a user’s excreta,” the researchers' paper states.

To analyze stool, it leverages “deep learning, with performance that is comparable to the performance of trained medical personnel.”

The stated benefit is, of course, is to consistently monitor a user’s health through their excrement and seamlessly deliver that information to medical professionals.

The toilet stores and analyzes the data it harvests in an encrypted cloud server.

Whether or not the cloud is greenish brown is unclear.

To further explore the world of the 2023 Ig Nobel Awards, check out the host website, Improbable Research.

Mushrooms are fascinating. They might taste like chicken, expand your mental horizons, or melt your insides, and there's very little middle ground. Firmly in the latter camp is the death cap — a widespread but unassuming little fungus responsible for 90% of mushroom-related deaths worldwide.

That's why it's such a relief that a team of scientists may have finally found an antidote.

To grasp how the antidote works, it's necessary to understand a little about the death cap. The mushroom originated in Europe, where it developed a symbiotic relationship with several types of hardwoods. As humans transported those trees to North and South America, Australia, and Asia for horticultural purposes, the death cap hitched a ride.

Looks good enough to eat, but isn't

In bad news for mycophiles worldwide, the death cap resembles several types of edible mushrooms — especially some varieties popular in Asian cuisine, according to The Guardian. Even worse, its primary toxin remains quite capable of shutting down your liver and kidneys even after you cook it. People who have eaten death caps and survived claim they are delicious.

"The most fatal component of the death cap is α-amanitin," a team of scientists at Sun Yat-sen University wrote in a study published in Nature Communications. "Despite its lethal effect, the exact mechanisms of how α-amanitin poisons humans remain unclear."

A modern approach

CRISPR gene-editing technology to the rescue, by way of good old trial and error.

The Sun Yat-sen team used CRISPR to create a group of human cells, each with a different mutation, Nature reported. Then the scientists exposed those cells to α-amanitin to see what happened. The result? Cells lacking an enzyme called STT3B could withstand the death cap's ferocious toxin. No one knows why.

"We are totally surprised by our findings," Guohui Wan, an author of the paper, told Nature.

The study didn't stop there. Next, the scientists set out to identify a compound that could block the action of the STT3B enzyme in cells.

The winner was a dye created by Kodak in the 1950s called indocyanine green. The dye already has widespread use in medical imaging applications, but its use as a possible mushroom antidote was entirely unexpected. And the initial data is promising. In the study, 50 percent of mice treated with indocyanine green within four hours of α-amanitin exposure survived. By contrast, 90 percent of untreated mice died from the toxin.

Some complications

Regarding human testing, the timing described in the above paragraph is the sticking point.

After the initial wave of gastrointestinal pain, nausea, and vomiting, many people poisoned by death caps begin to feel better (the "latent phase"). But the α-amanitin toxin is still in the system, insidiously destroying the liver and kidneys. By the time poisoned people show up at hospitals, it's often too late to save these vital organs.

Nevertheless, it's exciting that a mushroom responsible for so much suffering might soon be mastered. And the method by which scientists discovered the possible solution offers applications for other types of toxin/antidote research.

If you're tired of scientists stoking fear about deadly viruses, this story might not be for you.

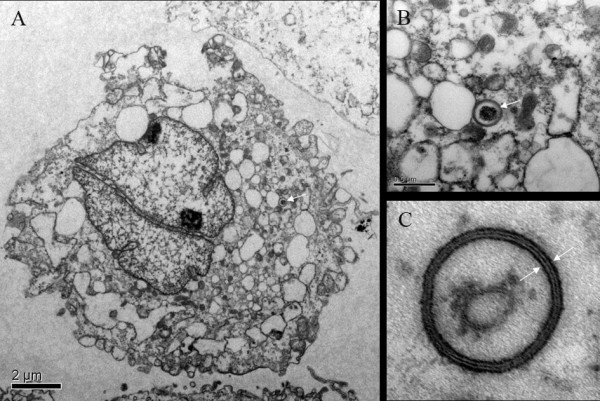

With a new study published on bioRxiv in November, a group of European researchers have sounded the alarm about "zombie viruses" emerging from melting permafrost in Siberia.

The scientists wrote that they have found and revived 13 such viruses from seven samples taken from Russia's remote tundra.

They call them zombie viruses because these ancient organisms can lay dormant for thousands of years while remaining infectious. One of the team's uncovered viruses, for example, had been frozen underwater for 50,000 years.

As climate change increasingly melts more of the world's permafrost, these scientists see potential problems ahead. (Note that this paper has not yet been peer-reviewed.)

"Due to climate warming, irreversibly thawing permafrost is releasing organic matter frozen for up to a million years," the paper said.

As a result, the viruses unleashed by climate change represent a potential "public health threat", according to researchers.

Climate change and ancient viruses

In the paper, these scientists ponder the risks of ancient viruses on modern populations as more permafrost melts.

So why on Earth would they revive them, you ask? Good question, and one these researchers felt prepared to answer.

Apparently, these scientists believe that "paleoviruses", or viruses uncovered by probing the bodies of frozen animals, like woolly mammoths, is much more dangerous.

Compared to that, the dangers of their own research is "totally negligible", the researchers wrote.

"Without the need of embarking on such a risky project, we believe our results with Acanthamoeba-infecting viruses can be extrapolated to many other DNA viruses capable of infecting humans or animals," they noted.

One-quarter of the Northern Hemisphere includes permanently frozen ground, or permafrost. Climate change will continue to melt that ground, likely resulting in much older viruses in the future.

"How long these viruses could remain infectious once exposed to outdoor conditions (UV light, oxygen, heat), and how likely they will be to encounter and infect a suitable host in the interval, is yet impossible to estimate," they said.

The word 'contagious' is not exclusive to colds, flu, and viruses. How about madness, laughter, and dancing? Incidents of mass hysteria or mass psychogenic illnesses are not as uncommon as you would think. In fact, they date back as far as the Middle Ages. The disturbing details of hundreds or thousands of people simultaneously engaging in erratic, hysterical, and sometimes violent behavior still baffles scientists.

Mass psychogenic illness (MPI) refers to a group of people experiencing various physiological symptoms without a contagion or environmental agent present. Recorded MPIs include symptoms like convulsions, hallucinations, dizziness, headaches, seizures, and muscle rigidity. In the cases below, some symptoms can be even more bizarre...

The dancing plague of 1518

In the early 16th century, the town of Strasbourg in northeastern France experienced immense hardships. They endured multiple crises, one after another: devastating floods, crop failures due to frigid temperatures, and violent peasant revolts. The summer of 1518 saw sweltering heatwaves which further weakened the community's agricultural prospects. The situation looked bleak.

One day, a woman named Lady Troffea started to dance in the street. Soon, several women joined her. The town chronicles record up to 400 townsfolk participating in this odd behavior. What might seem joyous turned macabre, with dancers collapsing from exhaustion and dancing to the point of gravely injuring themselves. The dancing lasted for days on end. The town council instructed doctors and priests to intervene, which led to a ban on music and instruction that victims wear red shoes dowsed in holy water and oil.

The epidemic stopped after the victims visited the shrine of St Vitus, the patron saint of dancers. One of the names for this dancing mania is the St Vitus Dance.

At the time, people believed the dancing was caused by demonic possession or a punishment from God. More modern scholarship hypothesized two theories, convulsive ergotism, and tarantism.

Convulsive ergotism occurs when the ergot fungi, which grow mainly on rye, produce a hallucinogenic chemical. Consequently, a person experiences erratic muscle movements, deterioration of the mind, and seizures. However, this theory seems unlikely based on the many variables and hundreds of people involved.

Tarantism refers to poisoning by a tarantula or scorpion which supposedly causes victims to try dancing to halt the coagulation of their blood.

A third, though less popular theory, is that it was a purely psychological issue. In this case, the mania would be stress-induced.

Salem witch trials

The Salem Witch Trials of 1692 and 1693 are the best examples of mass hysteria. In this small town in Massachusetts, locals accused over 200 people of witchcraft, they tried 30 of them, and then they executed 19 people. This brutal (literal) witch hunt, started with three pre-teen girls: Elizabeth Parris, Abigail Williams, and Ann Putnam. The three girls were said to be exhibiting disturbing behavior, including suffering from hallucinations, convulsions, making odd noises, feeling prickling sensations, and crawling on all fours.

Other girls in the town began to show similar symptoms. Word began to spread through the militant Puritan community that the girls had been practicing witchcraft and were possessed by the Devil. This led to immense panic and poorly organized trials where personal suspicions, bogus tests, and the power of suggestion overwhelmed any objective evidence.

Like the Dancing Plague of 1518, the most popular theory is convulsive ergotism. Rye was a common staple in Puritan households. It is possible that the ergot fungi developed when a harsh winter was followed by a warmer spring. Researchers found that the victims of ergotism were very impressionable and suggestible.

Another factor to consider is Salem's socio-economic difficulties. The environment in the town was already fearful before the cases arose.

Tanganyika laughter epidemic 1962

This 1962 incident in a small British-run girls' school in Tanzania demonstrates that laughter is not always the best medicine.

When a young girl began to laugh uncontrollably in class, her teacher removed her. But soon after, several other students followed suit. Not long after, much of the school had erupted into laughter and the principal canceled classes.

So, what was so funny? Unfortunately, there was nothing funny at all. The laughter was accompanied by crying, fainting, abdominal pain, violent tendencies, and even rashes.

The hysteria lasted for hours a day and continued for several months. The epidemic spread to other villages until over a thousand people were affected. The only convincing explanation to date is a stress-induced psychosis brought on by the parent's high expectations of their children.

West Bank fainting epidemic 1983

Between March and April 1983, a girls' school in Arrabah, Palestine was the epicenter of psychological and geopolitical strife. A large group of girls complained of dizziness, headaches, and stomach pains. Some of them fainted with no apparent environmental cause. Several female members of the Israeli Defence Force also fell victim to these random symptoms. Panic ensued.

Israeli and Palestinian media outlets scrambled to blame each side for bioterrorism and sabotage. Before authorities could come to a definitive conclusion, the symptoms spread to other villages like Hebron, Jenin, and Tulkarem, where over 900 people went to the hospital.

Investigators found small traces of hydrogen sulfide, methane, and hydrocarbons in the girls' bathrooms of the school. While it is possible for these gases to be a primary cause of the students' illness, what made people fall victim to the symptoms many kilometres away?

Authorities from Israel and the United States believed the incident to be a combination of stress caused by the current political situation, small doses of toxic gases, and a large number of psychosomatic experiences.

Arctic hysteria

Arctic hysteria or 'piblokto' is a folk illness or culture-specific ailment exclusive to Arctic communities. Women in these communities suffer from this mass psychosis, particularly during polar nights. The symptoms comprise hysterical out-of-character behavior and amnesia. Many women take their clothes off, shriek loudly and run around naked in the bitter cold. After this, they mostly forget having done it at all. Explorer Robert Peary and his family documented this phenomenon on an expedition to Greenland.

While some believe the women act out due to their society's suppressive nature, researchers believe the piblokto can be a response to the desolate conditions of the Arctic Circle and toxic levels of Vitamin A brought on by the Inuit diet. Too much vitamin A can simulate dementia and bring on delirium. These factors most likely work in conjunction with the harsh environment.

Mass psychogenic illnesses are strongly linked to stressful situations and scholars somewhat agree that erratic behaviors can be the brain's complex way of dealing with or alleviating stress. Women seem more susceptible to mass psychogenic illnesses, as yet, scientists don't know why.

Did we say quarantine? Well, today we suggest that you check twice for sudden changes of mind from Nepal's authorities. Barely 24 hours after announcing that all foreigners from 67 countries had to quarantine in a hotel for seven days after arriving in Kathmandu, the measure has been "postponed until further notice".

The original restriction affected travelers from most European countries, the U.S., and parts of Asia, where the Omicron variant of COVID is spreading fast. After the seven-day lockdown, foreigners would have to obtain a negative PCR test before moving freely within the country.

The Department of Tourism told The Himalayan Times that the Health Ministry recommended the measure. It was then shelved at the suggestion of Nepal's COVID-19 Crisis Management Centre, which thought that such a strict position would adversely affect international tourism.

The postponement doesn't mean that the quarantine won't reappear at any moment. Travelers heading to Nepal should check for updates before boarding the plane. It's also wise to keep the trip as flexible as possible and avoid tight schedules or immediate transfers out of Kathmandu. Just in case.

A passion for the natural world drives many of our adventures. And when we’re not actually outside, we love delving into the discoveries about the places where we live and travel. Here are some of the best natural history links we’ve found this week.

Dog DNA reveals ancient trade network connecting Arctic to outside world: Ancient arctic communities traded with the outside world 7,000 years ago. DNA analysis shows that Siberian dogs interbred with dogs from Europe and the Near East. Dogs have been central to life in the Arctic for thousands of years. Inuit and their predecessors used them to hunt, travel, and for clothing and food. The DNA analysis reveals that the trade networks of ancient populations may have extended down to the Mediterranean and Caspian Seas.

AstraZeneca Covid vaccine arrives in Antarctica: Nine months after it became available, the AstraZeneca COVID vaccine has made it to Antarctica. A series of increasingly small airplanes flew the vaccine 16,000km to immunize 23 staff members at the British Rothera station. For the entire journey, refrigeration kept the doses from 2˚C to 8˚C. Antarctica has stayed COVID-free, other than a few cases at the Chilean base.

Unmasking the gorilla's social distance habits

Gorillas also social distance: Mountain gorillas in Rwanda social distance from neighboring primate groups. Respiratory infections can be fatal for gorillas. Researchers have studied outbreaks among the primates for 16 years to decipher how these diseases spread. Though the disease runs quickly between individuals in a group, it rarely impacts other populations of gorillas. They found that when gorillas from different groups came into contact, they kept a distance of one to two metres.

Mass extinction 30 million years ago in Africa and Arabia: Scientists can now pinpoint when different mammalian species first appeared in Africa. The analysis of hundreds of fossils has created a family tree. Many fossil species disappeared around the Eocene-Oligocene boundary and then reappeared later in the Oligocene. Scientists think that a huge extinction event occurred around 30 million years ago, followed by a recovery period.

Finally, a malaria vaccine

World’s first malaria vaccine given go-ahead: Malaria is the largest cause of childhood death in sub-Saharan Africa. Every year, it kills over 260,000 kids under the age of five. The world health organization now recommends a vaccine for malaria in Africa. “This is a historic moment....a breakthrough for science, child health, and malaria control,” said WHO Director-General Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus. “Using this vaccine...could save tens of thousands of young lives each year.”

Giant ground sloths may have been meat-eating scavengers: Modern sloths are vegetarians, but their ice-age ancestors were opportunistic scavengers. Darwin’s ground sloths could grow to three metres long and weigh up to 2,000kg. Nitrogen isotopes in fossil hair samples showed that the ancient animals were omnivores, not herbivores as previously thought.

Why do pilot whales chase killer whales? Killer whales are the top predator in most places where they occur, but when pilot whales approach them, the orcas fall silent. This has surprised scientists. Killer whales in southern Iceland actively avoid pilot whales, and the pilot whales have been observed chasing the predator at high speeds. We aren't sure yet why this happens. The two species do not eat the same prey, and killer whales aren’t known to eat smaller pilot whales.

Thirty Chinese climbers, including a woman who set a speed record up Everest last month, have still not managed to get home from Kathmandu. Because of Nepal's COVID crisis, with daily infection rates still soaring at 24 percent, Beijing has not sent any planes to repatriate its citizens.

Although regular passenger planes are not flying, Nepal has allowed two charters per week from China. So far, none have come.

Getting home is harder than climbing Everest, says Tsang Yin-Hung of Hong Kong. Tsang, 44 summited the mountain in 25 hours 50 minutes from Base Camp, a new women's mark.

"The summit climb for me was possible," she said. "But going back home [is] hopeless...There are no flights to any place in China or Hong Kong."

Tashi Lakpa Sherpa of Seven Summit Treks estimates that 30 Chinese climbers remain in Kathmandu.