Camera traps in the jungles of Peru have captured footage of ocelots and opossums traveling together. We have at least four confirmed cases of the two animals walking in tandem, seeming to be perfectly aware and comfortable with the other's presence. The pairs were never more than two meters apart, moving at a leisurely pace. Their body language is relaxed, the opossum never attempting its famous "play dead" manoeuvre.

Experts believe that these aren't isolated incidents, but a pattern of behavior. A group of ecologists and researchers released a new study speculating on what that behavior could mean.

Sniff test

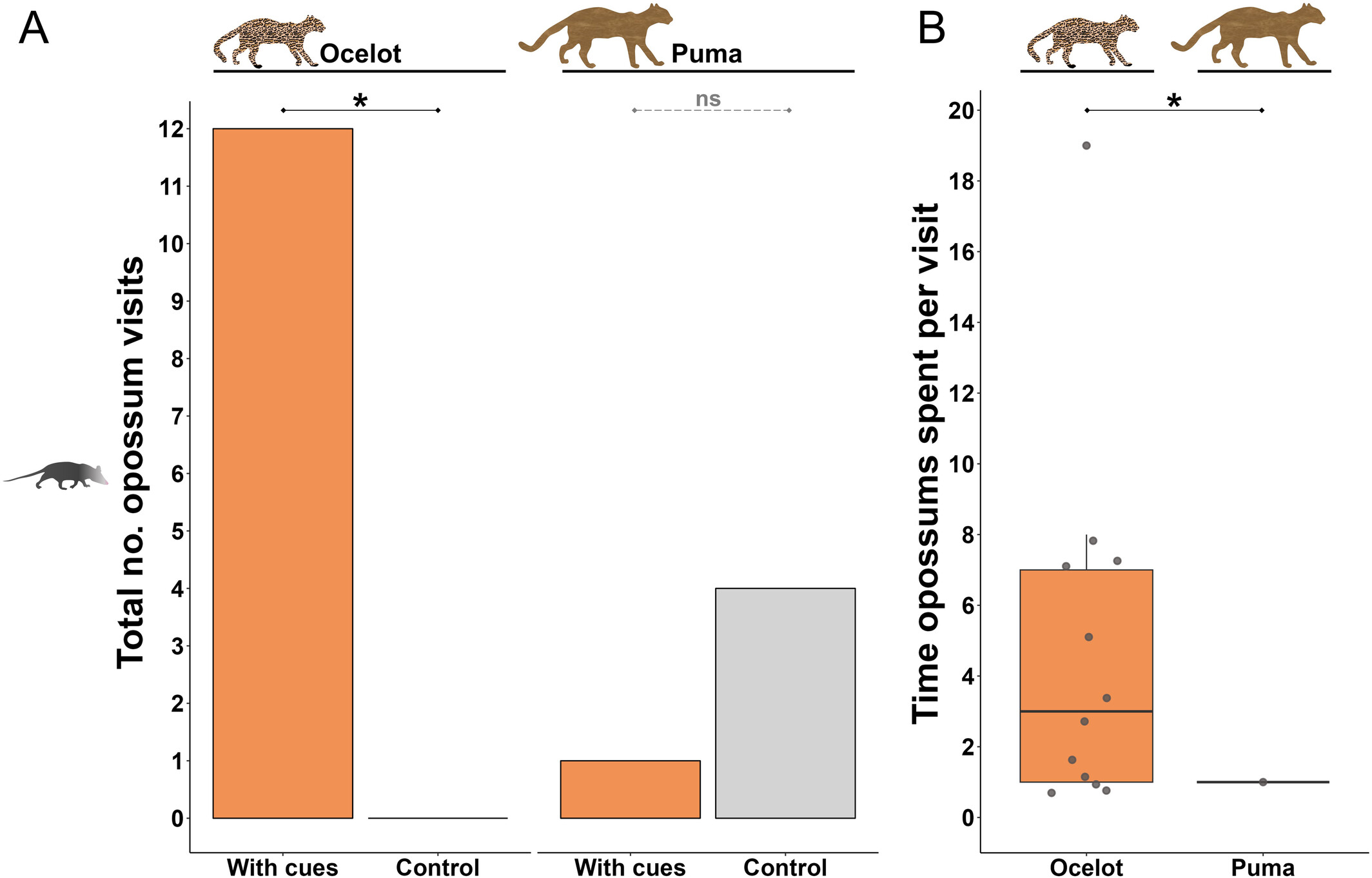

Before they developed formal theories, the researchers needed to collect more data. Ocelots might seek out opossums to hunt them, but would opossums actively seek out ocelots?

To find out, they set up camera traps with 'ocelot cues' -- items which gave off the scent of an ocelot, usually a strip of fabric -- and waited. Opossums showed up and even interacted with the ocelot cues, sniffing, biting, or rubbing themselves on the fabric. Opossums visited the ocelot-scented cameras far more often than control cameras.

To confirm that it was specifically ocelots that the little marsupials were interested in, they repeated the experiment. Using control and puma (cougar, catamount, mountain lion) scented traps, they observed that the opossums preferred the control, apparently disdaining the company of puma.

Both animals are solitary within their species, yet the ocelot and opossum don't just fall in together, but actively seek each other out. The question remains, why?

Much we don't know

Mutual partnerships between species are not rare and form when both sides have something to offer the other. Coyotes and badgers sometimes partner up to hunt burrowing prey. Their different adaptations and hunting strategies complement each other -- the coyote handles the chasing, and the badger handles the digging.

One theory is that the ocelot and opossum partnerships work much the same way. Opossums often feed on snakes and are even immune to viper venom, like the eponymous hero of Rudyard Kipling's short story Rikki-Tikki-Tavi. Perhaps the pairs team up to hunt serpents.

The researchers also speculate that moving as a pair may be a sort of camouflage. By moving with the notoriously odoriferous opossum, the ocelot could hide its scent, making it easier to stalk prey. Moving with the ocelot, the opossum would be safer from pumas and jaguars.

Ultimately, we don't know if one, both, or neither of these theories is correct. The study concludes with a call for more research, and a reflection on what this find reminds us: "how limited our understanding remains of the complex dynamics among tropical rainforest species."

Two killer whales have been caught "kissing" on camera in a fiord in northern Norway. A group of snorkelers-turned-citizen-scientists captured the moment last October, and now the internet is going wild for the smooching orcas.

This behavior, known as tongue-nibbling, has never been seen before in wild orcas. The snorkelers were on a whale-watching tour when they saw the two juvenile orcas approach each other and begin gently touching mouths and nibbling at each other’s tongues.

The video footage shows three separate interactions between the whales. Altogether, the whales spent nearly two minutes tongue-nibbling, a behavior that bears striking resemblance to French kissing. After their underwater make-out session, the two whales parted ways, swimming off in different directions.

Only seen a handful of times

Even in captive whales, this behavior is incredibly rare. It was first spotted in 1978 at Loro Parque Marine Park in Tenerife, Spain. Since then, only a handful of workers at marine parks have witnessed it.

"Orca caretakers at several facilities are aware of the behavior, but its prevalence is extremely low," study co-author Javier Almunia told LiveScience. "It may appear and then not be observed again for several years.”

The meaning of the behavior is open for interpretation. Some experts believe it’s a form of social bonding, similar to grooming in primates or the lip contact seen in beluga whales. Others suggest it could be play, part of how orcas express affection, or test social boundaries.

“Tongue-nibbling itself has not been recorded in other species, but comparable mouth-related social interactions have been observed in belugas," Almunia explained. "This could suggest that, given cetacean anatomy — particularly the adaptation of limbs to the marine environment — oral contact may serve as a more versatile means of social communication than in terrestrial mammals."

Others have speculated that it might be a way to clean each other’s mouths or beg for food. Regardless of the exact reason behind it, the kiss shows us that there is still a huge amount we don't know about cetacean behavior.

Natural behavior?

Those analyzing the footage believe that since this kissing occurs in wild orcas, it is a natural behavior also shown in orcas under human care.

Not all scientists agree. Some think that far more research is needed -- research that does not need captive whales.

“Even if the behavior itself is fascinating, and I think it is...it’s just one observation," marine mammal researcher Luke Rendall told LiveScience. "It is telling that in their summing up, these authors take great pains to explain how this observation justifies orca captivity and swim-with-cetaceans programs. It does not, in my view.”

In mid‑June, a rare case of mammalian altruism unfolded off the coast of Western Australia. A pod of dolphins escorted a young humpback whale from the confines of a shallow bay into deeper water.

Local conservationists from the Dolphin Discovery Centre spotted the humpback whale in Koombana Bay and were immediately concerned. Every year, the whales migrate roughly 5,000km from Antarctica to their breeding grounds near Australia’s Gold Coast. Humpbacks move along the coastline but do not usually venture into the shallow bay.

They quickly dispatched a boat crew to inspect the animal and sent drones to capture aerial footage.

“Sometimes it happens that an animal gets spooked by a predator, is [doing] poorly or injured, or might have a fishing gear entanglement," the Dolphin Discovery Centre commented. "These animals then often seek shelter in calmer and more shallow parts to rest up.”

The drone recorded the whale languishing near the bay’s edge. The footage showed no signs of entanglement or wounds. Just a whale that appeared a little bit lost. Then a curious pod of bottlenose dolphins appeared.

The dolphins started by circling the whale. Then came the pivotal moment. They began swimming northward, almost guiding the whale with purpose. The young humpback followed, moving into Geographe Bay’s deeper waters.

Dolphins are naturally sociable and curious, but this was more than a brief interaction. The footage seemed to show a coordinated effort, as if the dolphins recognized that the whale, possibly disoriented or exhausted from its migration, needed help. Inter‑species cooperation in the wild is incredibly rare. While marine animals sometimes travel together, they do not actively guide other species.

Dr. Vanessa Pirotta, a marine wildlife scientist, suggested that the dolphins might have even communicated with the whale.

“Whales use low-frequency sounds, while dolphins make high-frequency sounds, so I would assume these dolphins may have been buzzing around this whale," she said. "All in all, it looks like a very playful and innocent interaction between these two species.”

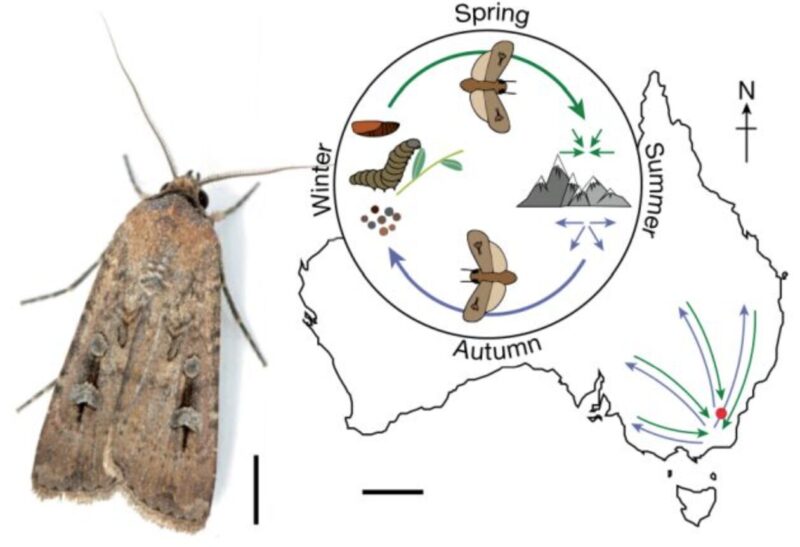

Each spring, millions of tiny brown Bogong moths fly 1,000km from southeastern Australia to the caves of the Australian Alps to escape the summer heat. Now we know how they find their way -- they navigate using the stars.

They have an innate ability to make this journey. After a few months in the caves, they return to their breeding grounds to mate and die -- so the next time they migrate, there are no individuals from a previous generation to show them the way. But somehow, the moths unerringly make it to a place they’ve never visited before.

Their journey can take weeks. The little moths fly each night and rest during the day, hiding up in whatever little crevices they can find en route.

“Their parents have been dead for three months, so nobody’s shown them where to go” said Eric Warrant, the author of the new study. "They just emerge from the soil in spring in some far-flung area of southeastern Australia, and they just simply know where to go. It’s totally amazing."

Magnetic field not as important

Warrant has studied the moths for years. He previously proved that they use the Earth's magnetic field to navigate, but he always thought there was more to the story. He believed that the moths had visual cues to guide them. As it turns out, the magnetic fields might play less of a role than previously thought.

To test his theory that the moths use the constellations, Warrant and his team set up a lab in his home near the Australian Alps. They designed a “moth arena” with a projection of the night sky on the ceiling. This perfectly mimicked the stars they would see if making the actual flight. To negate the impact of the magnetic field a Helmholtz coil was used, which creates a magnetic vacuum.

“We captured the moths using a light trap, brought them back to the lab, and then we glued a very thin rod on their back, made out of tungsten, which is nonmagnetic,” explained Warrant. "Once you’ve done that, you can hold that little rod between your fingers, and the moth will fly very vigorously on the end of that tether."

Positive proof

As the moths flew around the lab, an optical sensor detected their movement. In clear-sky tests, with accurate stellar projections above, the moths oriented themselves seasonally: flying south in spring and north in autumn. Astonishingly, when researchers rotated the star pattern, the moths adjusted their flight direction accordingly. If the stellar patterns were completely scrambled, the moths became disoriented, flying in every direction.

“That was, for us, like the final proof that they actually indeed use the stars for navigation,” said lead researcher David Dyer.

The experiment went even deeper. They then placed electrodes in the moths' brains to record neural activity. Researchers watched specific brain regions light up when the night sky shifted, especially as the insects faced south, the direction of migration.

Researchers now think that the Earth's magnetic field is more of a backup navigational system for the moths, used when heavy cloud cover blocks out the stars.

Other celestial navigators

We know there are several birds, seals, and frogs that navigate using stars. Birds such as Indigo buntings rely on the rotation of different constellations to figure out which way is south. In captive studies, harbor seals used specific stars or constellations to orient themselves. This may help them to search for food offshore.

The Bogong moth is the first invertebrate found to do this for such long migrations. Dung beetles (also an invertebrate) do use the stars to navigate, but only in a straight line over much smaller distances. They use the polarized light from the moon and the Milky Way to direct them as they push their dungballs.

Other moths use light sources like the moon to fly in a straight line by keeping the same angle to it -- but that is much less complicated than navigating an inborn direction by the stars.

Researchers hope that understanding their navigation will provide clues on how other insects figure out where they are going.

A young female bear spent last weekend roaming the leafy suburbs of Vilnius, the capital of Lithuania. She wandered out of the forest and then meandered around residential areas, crossed highways, and explored backyards, completely unaware of the commotion she was causing.

Her short city break quickly captured the nation. Onlookers trailed across the city, capturing footage of her on their smartphones and drones. Concerned for public safety, the Lithuanian government issued a permit to shoot the animal, causing uproar among the hunting community.

Members of the Lithuanian Association of Hunters and Fishermen categorically refused to carry out the order. Brown bears are scarce in Lithuania. The association thinks there are only five to ten individuals left in the country. They were once native to Lithuania but disappeared in the 19th century due to excessive hunting and habitat loss. Recently, small numbers have returned, migrating from neighboring Belarus and Latvia.

Lost, not aggressive

The association disagreed with the government's directive to shoot the bear, which is endangered and protected by Lithuanian law. This bear had shown no aggressive behavior. Ramute Juknyte, the association's administrator, told the Associated Press that the two-year-old bear was "a beautiful young female" and was frightened rather than hostile. “She just didn’t know how to escape the city, but she didn’t do anything bad.”

First spotted in the capital on Saturday, the bear finally came within four to five kilometers of the city center. At this point, the hunters suggested a different strategy to move her away from the city. They wanted to sedate, tag, and release her back into the wild.

In the end, none of this was needed. On her own, the young bear ambled back into the forest. By Wednesday, she had left the outskirts of Vilnius behind. A forest camera positioned 60km away recorded her quietly feeding on corn.

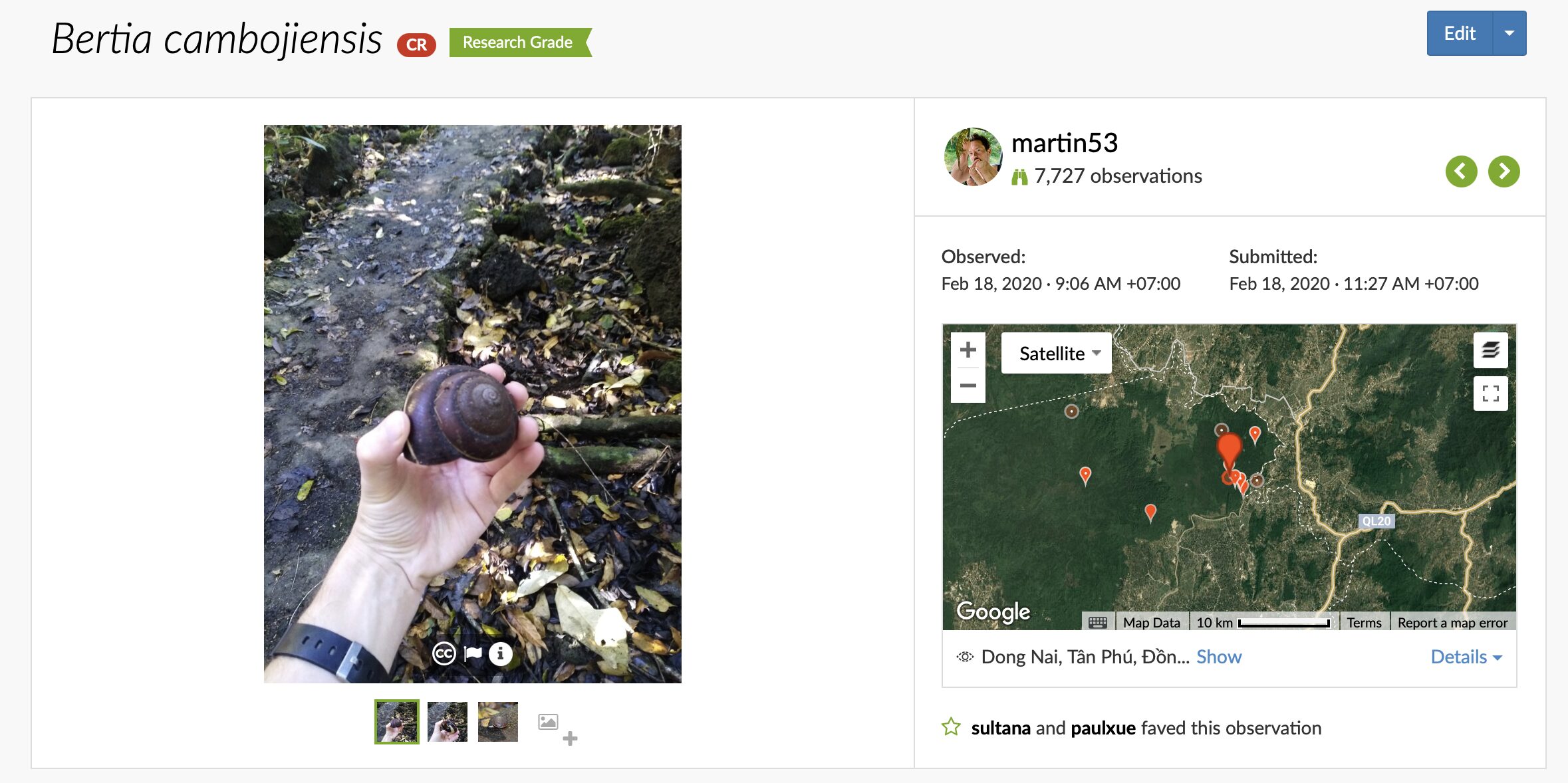

The tooth-billed pigeon, often dubbed the "little dodo," is one of the most elusive birds in the world. There are fewer than 100 left in the wild, and no one has photographed one since 2013.

Found only in Samoa, this critically endangered pigeon is uniquely adapted to island life. Its strong, curved beak allows it to eat tough native fruits. Between 4,000 and 7,000 roamed the island as late as the 1980s. Unfortunately, habitat destruction, hunting, and invasive species have pushed the bird to the edge of extinction. Locating one in the wild has been nearly impossible for years.

Now, the Colossal Foundation and several conservation partners have joined forces to find the bird using sound. The Colossal Foundation is part of Colossal Biosciences, the company best known for trying to revive extinct species like the woolly mammoth and the dire wolf.

The bioacoustic effort involves placing recorders in the forest to capture the sounds of wildlife. Later, researchers use AI to pick out the sounds that belong to the tooth-billed pigeon. By filtering thousands of hours of rainforest sounds, the AI algorithm can pick out promising audio clips that might reveal the bird's presence.

Bird sounds are like fingerprints

Sounds are critical identifiers for birds, and expert birdwatchers use sound more than sight to identify birds for their life lists. Birds call to attract mates, defend territory, and communicate with their young, and their calls are often as distinctive as fingerprints. That’s why bioacoustics has become an increasingly valuable tool in conservation, especially in hard-to-access areas.

A few researchers had previously attempted to use sound to find the endangered bird, but analyzing the data proved too difficult. Conservation officer Moeumu Uili, whose photo of a tooth-billed pigeon in 2013 is the last-known trace of it, admitted that "a significant gap remained in data analysis skills, limiting our ability to process results."

Colossal stepped in to address the issue. Using a five-minute audio clip of three tooth-billed pigeon calls recorded at Germany's Berlin Zoo in the 1980s, they created their AI algorithm. It analyzes recordings made in parts of the forest where the bird once lived. In a major breakthrough, it has identified 47 possible calls that offer hope that the Little Dodo may have survived.

While Colossal brings machine learning and acoustical analysis to the collaboration, the Samoa Conservation Society gives local knowledge and boots-on-the-ground support. Their team also installs and monitors the recording devices.

Verify the bird's existence is the first step to preserving its habitat and helping the population recover.

In the same way you can't prove a negative, "extinction" is always an informed guess. If we haven't seen hide nor hair (sometimes literally) of something for long enough, we have to assume it's not out there anymore.

But sometimes we assume wrong. Such was the case with the De Winton’s golden mole, which no one saw between 1936 and 2023, or the giant, elusive "ghost fish" of Cambodia's Mekong River. But finding these never-extinct-in-the-first place species is rare.

However, one more miracle reappearance has just occurred. Amid a global biodiversity crisis, the Asian small-clawed otter has emerged from hiding in Nepal to give otter enthusiasts hope.

The otter of the hour

The Asian small-clawed otter (Aonyx cinereus) is the smallest otter species on the planet, weighing only 2.7 to 3.5 kilograms. Its short claws, which give it its name, make it particularly dexterous, helping it pry open the molluscs and crabs it feeds on. These otters are very social and friendly, mating for life and often traveling in large family groups.

They're adaptable too, and live in a variety of different environments, including mangrove forests, swamps, swift rivers, stagnant pools, and rice paddy fields. In fact, rice farmers consider them helpful to have around, since they eat crabs, which farmers consider pests.

Small-clawed otters still live across Southeast Asia and into India. The last time they were officially seen in Nepal was 1839, so it's no surprise that they were considered extinct there.

Over the past few years, visitors to Makalu Barun National Park in the eastern Himalaya have reported scattered, unverified sightings of the little otter. But it remained elusive until forestry officials stumbled upon it.

The once and future Asian small-clawed otter

A bulletin by the IUCN/SSC Otter Specialist Group announced the confirmed presence of the Asian small-clawed otter in Nepal. The discovery of a surviving Nepalese otter population came when a local from Dadeldhura village found an injured baby otter by the Rangun and Puntara Rivers. Not knowing the significance of the little creature, the local passed it on to local forestry officials.

The Forestry Officer, Rajeev Chaudhary, thought it might be a small-clawed otter. While he was nursing it back it health, he took photos and videos of the pup. Chaudhary then sent them to Nepalese otter experts at the IUCN Otter Specialist Group. They confirmed his suspicions and set about a habitat study in the area. Meanwhile, the pup in question recovered its strength and was released back into the wild.

Asian small-clawed otters are listed as Vulnerable to Extinction. This discovery doesn't change that. The fact that these tenacious little otters are clinging on to their ancestral territory in Nepal is only more reason they need immediate support.

For one thing, they aren't on Nepal's Aquatic Animal Protection Act list. The river ecosystems they inhabit are threatened by mining, over-fishing, agricultural run-off, and deforestation. Getting official protection, now that they officially exist, is crucial.

"A timely conservation effort for this exceptionally rare species, a keystone aquatic mesocarnivore, is now urgently needed in Nepal," the IUCN bulletin concludes.

We are the worst primates when it comes to wound healing, according to a new study. Our wounds heal nearly three times slower than those of chimpanzees, our closest living relatives, and other primates and mammals.

Evolutionary biologist Akiko Matsumoto-Oda was watching wild baboons in Kenya when she noticed their wound-healing abilities. The monkeys could be very violent and aggressive with each other, and often sustained injuries.

“I was struck by how rapidly they recovered — even from seemingly severe wounds,” she told The New York Times.

Her intrigue triggered new research at how skin wounds heal in a controlled environment for various primates and mammals. The study included humans, chimpanzees, olive baboons, Skye’s monkeys, vervet monkeys, mice, and rats. The 24 humans were all volunteers and patients from Japan's University of the Ryukyus Hospital. All were having skin tumors removed.

The monkeys, rats, and mice came from various research facilities. Some had been injured in fights. A very few were anaesthetized and surgically wounded. “As a field researcher, I personally believe that invasive studies should be minimized,” Matsumoto-Oda explained.

Human skin regrew 2.5 times more slowly

Humans regrew their skin at around 0.25mm per day, while the other primates and mammals exceeded this. Skin regrowth proceeded at approximately 0.62mm per day. The team discovered that there was no significant difference in the healing rate of the other primates or between the other primates and the rats and mice.

Why humans heal so much more slowly seems to lie in our evolutionary past.

“We found that chimpanzees exhibited the same wound-healing rate as other non-human primates, which implies that the slowed wound-healing in humans likely evolved after the divergence from our common ancestor with chimpanzees,” says Matsumoto-Oda.

The exact reason for this is unknown, but one possibility is our loss of body hair. Unlike most mammals, we developed a dense network of sweat glands to cool down more efficiently. This adaptation helped early humans survive in hot climates and allowed them to run and hunt over long distances without overheating. However, this trade-off came with a hidden cost.

Animals covered in hair are also covered in hair follicles, and these contain stem cells. Usually used in hair formation, these stem cells appear to give other mammals an edge when they have a cut or scratch.

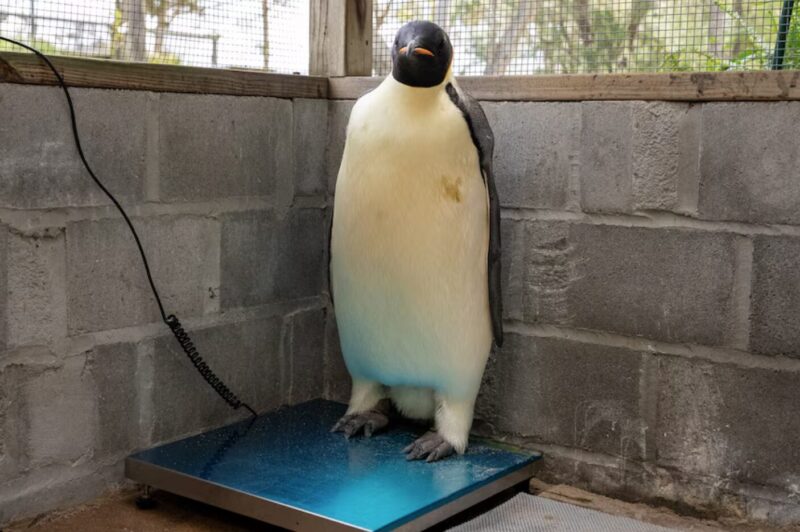

A three-penguin race on Galindez Island, site of the Ukrainian Antarctic Expedition, concluded on Tuesday. The victory went to a newcomer to the racing scene, Unidentified Penguin #2. Unfortunately, no penguin equivalent of FastestKnownTime.com exists, but we encourage the penguin-loving community to create one.

Not professional racers

Penguin racing often flies under the radar. Averse to social media, many champion FPT-setters also have day jobs as penguins, doing penguin things like diving for fish. Fortunately, the Ukrainian Antarctic Expedition (UAE) filmed the first half of the Galindez Island race.

"This video is for those who still doubt that penguins are surprisingly fast creatures," wrote the UAE on Facebook.

In the video, the eventual winner races neck and neck with two other penguins. The three-penguin lead pack jostles for space. A large part of penguin racing appears to be strategy: when to waddle like a weird little windup toy versus coast on one's belly like a sled? Penguins can accelerate to 6kph on their bellies, but navigating difficult ground requires a combination of the two modes of transport.

Penguins are even faster in water, reaching speeds of 36kph.

The purpose of the race remains unclear

While setting the FPT on Galindez Island is a worthy goal, the exact nature of this race has not been confirmed.

"This trio must have had extremely important things to do," the UAE suggested. "Was it krill again at a discount, or did they bring a truckload of pebbles from a neighboring island?"

Penguins are very social birds, nesting in large groups and often mating for life. A penguin in veterinary care at the Perth Zoo made headlines in 2021 for its investment in watching episodes of Pingu on an iPad. And in Japan's Tobu Zoo, a penguin captured the internet's heart by apparently falling in love with a cardboard cutout of an anime character.

Still, documented evidence of racing on land is a rare treat.

Each spring, the Farne Islands off England's Northumberland coast transform into a seabird heaven, with puffins center stage. This year, to mark the 100th anniversary of the National Trust's stewardship of the islands, two webcams have been set up so that anyone can watch the charismatic little birds.

The archipelago hosts approximately 200,000 seabirds each year, including 50,000 breeding pairs of puffins. Each spring, they return from their winter haunts to nest in the same burrows they've used for years.

The first camera sits beside the puffin burrows. Initially, you will likely see male puffins trying to defend their territory. As we head into July, young pufflings will start to appear. The second camera will show the cliffside, where over 20 species of seabird that breed on the islands, including guillemots, shags, kittiwakes, razorbills, and peregrine falcons, cohabit with the puffins.

Each year, conservationists monitor the puffin population by gently extracting them from their burrows and weighing and measuring them. From 2020 to 2024, this work paused because of the pandemic and various avian flu outbreaks.

A stable population

The 2024 count revealed a relatively stable puffin population, which offers hope amid the dwindling numbers of other seabird species. Some, such as European shags and arctic terns, have suffered significant losses because of disease and severe weather.

Beyond the Farne Islands, the Alderney Wildlife Trust in the Channel Islands has also set up live streams from its puffin colony on Burhou Island. Similarly to the Farne Islands, they have two cameras. Their Puffin Main Cam and Burrow Cam should capture the daily activities of the birds, from burrow maintenance to feeding routines.

Despite the positive signs, puffins continue to confront numerous threats. Climate change, marine pollution, and overfishing all create hardships. Researchers have begun tagging puffins for an in-depth study of their lifespans and migration patterns to better understand the threats the colorful little birds are facing.

Scientists have discovered two unknown species of crocodile on islands off Mexico's Yucatan Peninsula. They were always assumed to be American crocodiles (Crocodylus acutus), but new genetic testing proves they are distinct.

Researchers from McGill University and collaborating Mexican institutions found that the isolated crocodiles differed in several ways from their mainland relatives.

"The results were totally unexpected," said lead author Jose Avila-Cervantes in a statement. "We assumed Crocodylus acutus was a single species ranging from Baja California to Venezuela and across the Caribbean."

The two yet-to-be-named new species live on Cozumel Island and the Banco Chinchorro atoll. Their isolation caused them to adapt to their unique environments, beginning about 11,000 years ago.

Besides DNA disparities, physical exams revealed noticeable differences in skull shape and scale patterns. The Cozumel crocodiles have long and narrow "longirostrine” snouts that may be an adaptation for catching specific prey. Meanwhile, the Banco Chinchorro crocodiles have broader skulls that help them crush hard-shelled prey.

Each population contains fewer than 1,000 breeding individuals, and their restricted habitats make them susceptible to climate change and human activities, such as coastal development.

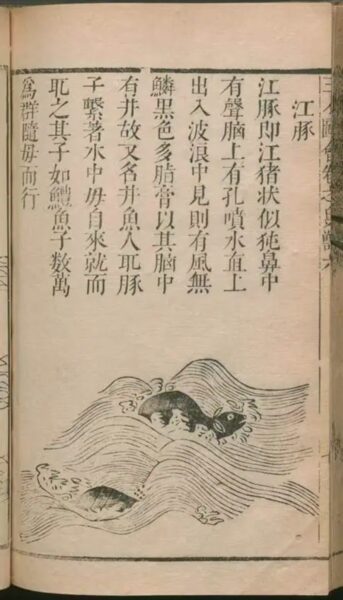

For centuries, the Yangtze porpoise was a common sight on the river it is named after. Now, the freshwater mammal is critically endangered, rarely sighted, and only found in a tiny proportion of the huge waterway that winds from the Tibetan Plateau to the East China Sea. To track the species' decline, researchers have turned to an unusual source— ancient Chinese poetry.

Researchers analyzed 724 ancient Chinese poems that referenced the Yangtze porpoise. Some date back to the Tang dynasty (618–907 CE). Penned by scholars, emperors, and poets who often traveled along the Yangtze, the poems provide vivid accounts of the porpoise's presence and behavior.

“Our work fills the gap between the super long-term information we get from fossils and DNA and the recent population surveys," said Zhigang Mei, co-author of the new study. "It really shows how powerful it can be to combine art and biodiversity conservation.”

Harming the porpoise was bad luck

The Yangtze finless porpoise holds an important place in Chinese folklore. Mei remembers the elders in his community speaking of them as spirits, believing they could predict weather changes and good fishing. Harming the creature was considered bad luck. This is perhaps why they featured so heavily in ancient poetry.

To ensure accuracy in the poem's content, the researchers cross-referenced the information in the poem with what they knew about that author's life. They identified where each poet lived and traveled to ensure that it matched the information within their poems. This approach allowed them to extract reliable ecological data from the verses.

Using the poems with historical records, they mapped the porpoise's distribution across different dynasties. Poems from the Qing dynasty referenced the porpoises 477 times, whereas they appeared slightly less in earlier periods.

Despite this, there was a clear pattern. Over time, a sharp decline in porpoise sightings has occurred. Tributaries and lakes associated with the river had a 91% decrease; the main river channel had one-third fewer. Overall, the findings reveal a staggering 65% reduction in the porpoise's habitat over the last 1,400 years.

Causes of decline

Poets like Emperor Qianlong of the Qing dynasty often described the porpoise's playful antics, especially its tendency to leap from the water in stormy weather.

“Compared to fish, Yangtze finless porpoises are pretty big, and they’re active on the surface of the water, especially before thunderstorms when they’re really chasing after fish and jumping around,” explained Mei. "This amazing sight was hard for poets to ignore."

Since the 1950s, new dams have made huge sections of the river inaccessible to the porpoises. Pollution and fishing have also affected the porpoise populations.

With fewer than 1,800 freshwater porpoises left in the river, conservationists are worried they will follow the same path to extinction as their cousins, the Yangtze River dolphin.

“Protecting nature isn’t just the responsibility of modern science; it’s also deeply connected to our culture and history,” said Mei in a statement. "Poetry can really spark an emotional connection, making people realize the harmony and respect we should have between people and nature.

A bird once declared extinct in the wild has just laid eggs in Hawaii.

The sihek, also known as the Guam kingfisher, has a striking burnt orange breast, electric blue wings, and a sharp beak. Native to the island of Guam, the tiny birds thrived until the accidental introduction of the brown tree snake in the mid-20th century. Sihek populations plummeted. By 1988, the bird was declared extinct in the wild.

The sihek became a feathered example of what can happen when an invasive species runs wild. The bird didn’t vanish entirely because of a last-minute rescue operation. Conservationists captured 29 of the remaining siheks and began a careful breeding program.

Several institutions have been raising siheks for the last few decades, trying to increase their numbers. Last year, some donated eggs to a special facility at the Sedgwick County Zoo in Kansas. Here, the hatchlings were cared for until they were old enough to journey to the atoll.

Researchers released nine of the hand-reared siheks in September 2024. They were rewilded in The Nature Conservancy’s (TNC) Palmyra Atoll Preserve, which lies around 1,600km south of Honolulu. They chose this area because the birds have no predators there, and the area is fully protected.

One lonely male

The four females and five males formed four breeding pairs. (One lonely male didn't have a mate.) Less than a year later, all the pairs established territories, built nests, and laid eggs in the wild for the first time since the 1980s.

“This is a huge win," said John Berry of the Cincinnati Zoo. "It means the birds are not just surviving—they’re beginning to thrive.”

Though everyone is excited about the new eggs, they also admit it is very unlikely that they will survive. The mating pairs are less than a year old and have never had to care for eggs and incubate them before. It often takes a few attempts at laying and looking after eggs for them to actually hatch.

Conservationists are now planning to release more young siheks onto the atoll later this year.

Forget the latest Netflix and Amazon Prime offerings -- right now, one of the hottest shows on the planet is a 24/7 live-stream of moose slowly migrating through the Swedish wilderness.

Dubbed The Great Moose Migration, this unlikely sensation is exactly what it sounds like. Hours of footage show moose slowly plodding through forests and wading across rivers. Viewers can’t get enough.

Broadcast by SVT (Sweden’s public broadcaster), the event was first live-streamed in 2019. It was created as part of a wider "Slow TV" movement showing real-time footage of mundane activities; think knitting and train rides. Unlike other shows, there is no backing music, commentary, or editing. It is exactly what is caught on camera. What started as a quirky local experiment quickly became a hit. A million viewers tuned in during the first year. Last year, that had increased to nine million.

Deeply soothing

It seems there is something deeply soothing about watching the slow, lolloping animals wander through a pine forest along this ancestral route to their summer grazing spots. With 26 remote cameras and seven night cameras, the show cuts between the various spots to show what is happening. For large swathes of time, there may be no moose in the shot at all.

Despite this, some viewers watch for almost 24 hours a day. Others admit to setting up separate screens so that they can have it on in the background as they work. Mega-fan Ulla Malmgren said she had purposefully stocked up on snacks, pre-prepared meals, and coffee so that she could watch the 20-day migration.

Due to unseasonably warm weather, this year's migration started a week earlier than usual, but fans were ready. Some 77,000 are part of a Facebook group that provides updates on the migration. It is expected to last until May 4. With panoramic shots, long silences, and the occasional splash as a moose crosses a river, the live-stream is oddly hypnotic.

Long lulls

SVT puts out notifications on their app when a moose appears on camera, so viewers don’t miss the excitement. Sometimes, hours pass with nothing but swaying trees and chirping birds. Then, suddenly, a moose appears — and the chat explodes with excitement.

The live stream focuses on a key stretch of the annual route in northern Sweden, where the animals are funneled toward a few river crossings. There are around 300,000 moose in Sweden, but they are notoriously shy creatures.

“We actually don’t see them very often,” explained SVT project manager Johan Erhag. "I think that’s one reason why it has been so popular. You bring nature to everyone’s living room."

So if you’re looking for a way to de-stress, or just need a weirdly captivating distraction, consider tuning in. No plot, no dialogue, just moose.

BY RACHELLE SCHRUTE

In a groundbreaking leap reminiscent of Jurassic Park, scientists have successfully revived the dire wolf, an apex predator that vanished nearly 13,000 years ago.

The revival project, spearheaded by startup company Colossal Bioscience, used advanced DNA editing techniques. By sequencing ancient DNA samples recovered from fossils preserved in tar pits, researchers reconstructed a complete genome of the dire wolf, closely related yet distinctly separate from modern grey wolves.

Two male pups, Remus and Romulus, were born in October 2024, followed by a female named Khaleesi in January 2025. Fans of HBO’s Game of Thrones will likely recognize both the creature and the inspiration behind their names.

But are these really dire wolves or just genetically modified grey wolves? That “grey” area is up for interpretation.

While Stanford led the genetic effort, biotech startup Colossal Biosciences played a pivotal role in bringing the project to life. Known for its mission to resurrect the woolly mammoth, Colossal provided logistical support, funding, and proprietary gene-editing tools that accelerated the dire wolf program.

Colossal’s involvement also sparked public curiosity, thanks in part to its high-profile partnerships and unapologetically bold marketing. I mean, just take a look at the company’s website. It’s hard to decide whether it’s legit or a carefully crafted sci-fi movie promo.

CRISPR to the Rescue

Using CRISPR (Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats) technology, the team introduced precise genetic edits into embryos of modern wolf relatives, effectively recreating dire wolf traits. After several attempts, the first litter of dire wolves was successfully born last fall in a controlled facility in Montana.

These animals are designed to thrive in rugged, challenging environments. The project’s next step involves assessing their viability in protected wilderness areas.

Dire wolves, once dominant across North America, were notably larger and sturdier than today’s wolves, capable of taking down massive prey such as bison and giant sloths. Their reintroduction could radically reshape modern ecosystems, presenting both exciting opportunities and ecological challenges.

The project has sparked vigorous debate within the conservation community. Supporters view it as a monumental achievement in species restoration, while skeptics caution about potential risks to existing wildlife.

Are they actually dire wolves?

This article first appeared on GearJunkie.

When you think of dangerous animal encounters and surfing, you immediately think of sharks. But something completely unexpected attacked RJ LaMendola when he was surfing off Oxnard, California. Around 140 meters from shore, a sea lion chased him down and bit him.

Showing highly erratic behavior, the animal charged at him with alarming speed, mouth agape, and eyes locked onto him. Despite his efforts to evade the deranged sea lion, it bit him on the left buttock, dragging him off his surfboard and into the water. LaMendola managed to fend off the attack and paddle back to shore, where he sought medical attention.

Posting about the incident on Facebook, LaMedola said, “It started as an ordinary session…The ocean was calm, the rhythm of the swells familiar — until, out of nowhere, a sea lion erupted from the water, hurtling toward me at full speed…My heart lurched as I instinctively yanked my board to the side, paddling frantically to evade it as it barrelled forward, intent on crashing into me.”

Continued the attack

Even after the sea lion bit him and wrenched him from his board, it continued to pursue him as he tried to get back to shore.

“Its expression was feral, almost demonic, devoid of the curiosity or playfulness I’d always associated with sea lions,” he recalled.

Back on land, LaMendola drove himself to the hospital where the bite was treated. It should heal fully, but LaMendola is still shaken and concerned about getting back into the water. He contacted local wildlife authorities to report the incident. The attack comes amidst a growing number of incidents involving sea lions and dolphins in Santa Barbara and Ventura County. It highlights a growing environmental crisis along the California coast.

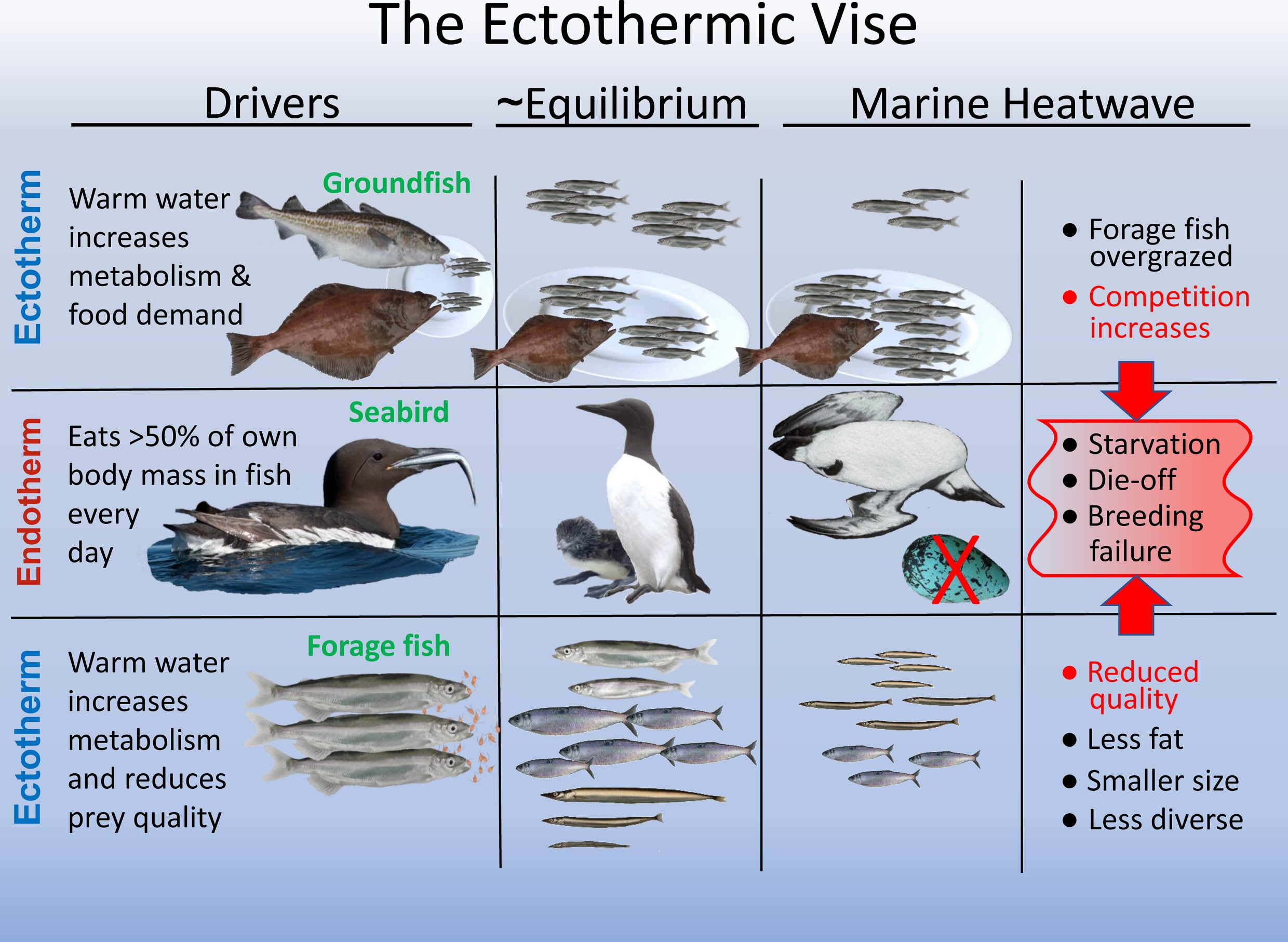

Sea lions and other marine mammals are displaying unprecedented aggression due to domoic acid poisoning. Harmful algal blooms flourishing along the coastline release a neurotoxin called Pseudo-nitzschia. The toxin accumulates in fish like anchovies and sardines, which are primary food sources for sea lions and dolphins. When these marine mammals chow down on the contaminated fish, they take in the toxin, which affects their brains and leads to seizures, disorientation, and aggressive behavior.

A deadly plague

The current algal bloom has had devastating effects on marine life in Southern California. The Marine Mammal Care Center in San Pedro is caring for over 140 sick sea lions, with a further 45 at the Pacific Marine Mammal Center and another 15 at SeaWorld San Diego. Wildlife authorities in the area are being inundated with calls about dolphins and sea lions washing up on shore. Though they can treat poisoned sea lions, the same cannot be said for dolphins. Vets have to euthanize the beached cetaceans, as they rarely survive domoic acid poisoning.

These toxic blooms are worsening due to warming oceans and agricultural pollution. In 2023, thousands of marine mammals died, and this year's algal blooms could be even more devastating.

The birds of the Galapagos Islands gave Darwin some of his best evidence for evolution. Now some of those birds have evolved an extreme dislike of all the noise of this increasingly busy tourist destination.

A new study suggests that traffic noise affects the behavior of the Galapagos yellow warbler. The little yellow birds are altering their songs, and the males have become more aggressive. Think of it as the avian version of road rage.

Birdsong is a crucial tool for male warblers to defend territories from rivals. External noises, such as traffic, hamper the effect of their songs. Rather than fend off competitors with their vocal stylings, the little birds resort to physical aggression instead.

Researchers from Anglia Ruskin University and the Konrad Lorenz Research Center carried out experiments at 38 sites across the islands of Floreana and Santa Cruz. Researchers played recorded bird songs in all those locations, mimicking an intruder. Some songs had accompanying traffic noise, and others did not. The responses varied significantly based on how close the birds lived to the road noise.

Change of tune

Warblers near roads were aggressive when the combined sounds of rival bird songs and traffic played. They approached the source of the sound, increased their physical displays, and prepared to fight. By comparison, birds in quieter, more remote areas showed far less aggression. Researchers believe this is due to their unfamiliarity with traffic noise.

The warblers also changed their singing because the traffic noise masked their normal birdsong. To counteract this, the clever birds adjusted the frequency of their singing so that their calls were still audible over ambient traffic.

“We have to think about noise pollution even in places like the Galapagos,” co-author Çaglar Akçay told The Guardian. "The results of the study are clear: Human-induced noise pollution is affecting wildlife behavior, even in remote and protected regions like the Galapagos."

Shark researchers at Australia's University of Auckland were surprised recently to see an orange octopus perched atop a mako shark. They sent up their drone and captured a delightful if mystifying video.

'Sharktopus'

The research vessel was near the northern coast of New Zealand, studying shark feeding, when they spotted a large short-fin mako shark just underwater.

The patch of orange on top of its head confused them. Marine scientist Rochelle Constantine initially thought they were seeing a shark entangled in fishing gear. They sent up a drone to look closer, and that's when they realized the orange blob was a living animal.

The Maori octopus is one of the biggest octopuses in the southern hemisphere and can weigh 12 kilograms fully grown. Known for being rather ill-tempered and aggressive, they usually live on the seabed. Mako sharks, meanwhile, prefer shallower waters. The two species shouldn't even have met, yet alone interacted in this peculiar way.

The "sharktopus," as the amused researchers dubbed it, is a previously unrecorded phenomenon. Octopuses are famously intelligent, enough to work cooperatively with other species, and may act as strict leaders of mixed fish-octopus hunting parties. But researchers aren't sure whether the octopus intended to ride on a shark's head.

World's fastest shark

Like many octopus species, the formidable Maori octopus has a paralyzing neurotoxin that it uses to hunt. It can grow up to a meter long and may go after larger animals than itself, grasping with its strong, thick arms.

Not mako shark large, though. Also known as the blue pointer or bonito shark, the shortfin mako can be up to four meters long and 570 kilograms. They are also the world's fastest shark, hitting speeds of up to 50kph. The Maori octopus would have to make full use of its strong arms to hold on for dear life.

The Gulf where they recorded the sharktopus is considered an important shark conservation area. It is the home and breeding ground of many shark species, including the endangered shortfin mako. For Constantine, the encounter is a reminder of the mystery and wonder of the ocean.

Millions of years ago, a group of adventurous iguanas did something no one expected. They crossed the Pacific Ocean from the Americas to the islands of Fiji on giant rafts of vegetation.

The iguanas in Fiji and Tonga have always been an evolutionary puzzle. Iguanas are native to the Americas and the Caribbean, but somehow millions of years ago, a small group of them made it all the way to Fiji. There was never land bridge between the two distant places. So how on Earth did they get there?

Evolutionary biologist Simon Scarpetta of the University of San Francisco and his colleagues think they have solved the mystery. They believe the reptiles caught a lift across the ocean on a platform of trees, plants, or debris. These rafts occasionally break off from coastlines and drift out to sea as floating islands. Animals on them may wind up in new and unexpected destinations. In the case of the Fijian iguanas, researchers believe they made a record-breaking trip by drifting over 8,000km across the Pacific Ocean.

“You could imagine some kind of cyclone knocking over trees where there were a bunch of iguanas and maybe their eggs, and then they caught the ocean currents and rafted over," Scarpetta told The New York Times.

Masters of survival

It is quite rare for vertebrates to survive such trips. But iguanas can go weeks without food or fresh water, making them well-suited for long voyages of deprivation. They have been seen rafting before, but their journeys have never been this long. In 1995, a group of about 15 iguanas were spotted hitching a ride 320km between Caribbean islands aboard hurricane debris. The team thinks their slow metabolism and rainwater allowed them to survive the incredibly long journey to Fiji.

There have long been two hypotheses about these out-of-place reptiles. First, that they rafted over from the Americas; and second, that a now-extinct ancestor drifted over from Asia or Australia.

Scarpetta and his team studied the evolutionary history of over 200 species of iguanas and lizards. The four species in Fiji are most closely related to the desert iguanas of Mexico and the American Southwest. That is clearly where they came from, although the timing of their great voyage remains uncertain.

"This suggests that as soon as land appeared where Fiji now resides, these iguanas may have colonized it," Scarpetta said. "Regardless of the actual timing of dispersal, the event itself was spectacular."

Hummingbirds are famously the smallest birds in the world, but they are also surprisingly aggressive with each other. Because they are so territorial, you would never think of them as living amicably in colonies. Yet one unusual species in Ecuador is nesting in colonies in the High Andes.

When ornithologist Gustavo Cañas-Valle stumbled upon this fraternization among the Chimborazo Hillstar hummingbirds, he couldn’t believe his eyes.

“It was mind-boggling," he said in a statement. "Finding them nesting in the same location was amazing. Then I realized that males and non-reproductive females were also roosting in the same space as reproductive females." That, he said, was even stranger.

Hummingbirds are especially territorial during feeding and nesting. Females typically nest alone, while males ferociously defend their territories, sometimes to the point of fatal confrontations. The discovery of these hummingbirds that are so chummy with each other suggests that they have adapted because of environmental pressures.

Not like penguins

“Hummingbirds are not a species like penguins where you see hundreds of them together,” co-author Juan Bouzat explained. "These are hummingbirds that live in the High Andes, above 10,000 feet, in a very, very harsh environment above the tree line."

Cañas-Valle identified 23 adult birds and four chicks nesting and roosting within a single cave. This particular cave sits over 3,600m above sea level. Nearby vegetation is almost nonexistent, shelter is sparse, and temperatures at that altitude can be frigid despite its location on the equator.

Cañas-Valle and Bouzat wanted to determine whether this sociability was solely due to the harsh conditions and a lack of nesting sites or if it also occurred elsewhere.

The research duo scoured the area, identifying several places where solitary nesting would be possible. While some were in use, a large proportion were not. Instead, 80% of the active nests they found were within colonies. The study suggests that the birds prefer to live together rather than were forced to.

Bird colonies usually exist because the individuals benefit from living together.

“Somehow, they get a benefit...from the social group,” said Bouzat.

Exchanging information?

What that benefit is remains up for debate. Cañas-Valle regularly saw hummingbirds leaving and returning to the cave together. He speculates that the members of the colony may be exchanging information about the location of food and mates.

The situation is so unusual for hummingbirds that some experts question whether the birds are actually showing colonial behavior. Cañas-Valle and Bouzat understand the skepticism. Cañas-Valle joked that it took years just to convince his colleague.

“It took me probably two years for Juan to say, ‘Well, Gustavo, you convinced me. We can call this gathering of nests a colony from now on,’” he said. “I was thinking,’ Finally.’ That was a priceless moment.”

Disease tops nobody's list of Antarctic dangers. "The great advantage of this place is that one never gets ill," said Robert Falcon Scott. His contemporary, Douglas Mawson, even suggested that the icy continent would be an ideal place for tuberculosis sufferers to recover due to the lack of germs.

A lot can change in a hundred years.

Deadly new strain

It's been over five years since a new, deadly strain of Avian flu, called HPAI H5N1 clade 2.3.4.4b, began decimating global bird populations. There have been significant outbreaks in the UK, Europe, South Africa, and the Americas. The disease targets not only birds but also pinnipeds like seals, walruses, and sea lions. Last year, it finally landed on the Antarctic Peninsula.

But scientists could do nothing, not even monitor the situation. During the long, black winter, they were unable to study the progress of the disease. As soon as conditions allowed, a research team about the Australis crossed the Drake Passage into Antarctic waters. They were led by Spanish virologist Antonio Alcamí, who had identified the first case a year earlier.

The ship, equipped with a state-of-the-art lab, visited dozens of sites along the peninsula's coast and in the Weddell Sea. What they found wasn't encouraging.

Widespread infection

In total, they collected and tested 846 samples, and 188 tested positive for H5N1. The infected animals were from nine bird and four seal species. The animals they tested had a high viral load, making them highly infectious to other animals around them. Carcasses, especially, are a vector, and because of this the skua, a carrion-bird, has been especially hard hit.

The disease has spread geographically, too. The virus was present in 24 out of 27 sites they visited, ranging down the arm of the peninsula and across various Antarctic and subantarctic islands, including South Georgia. The older infections were on the north side of the peninsula, where visitors observed lower populations, especially of the skuas. On the south side, the outbreak is more recent, and visitors can see dead and dying seabirds.

No infections have been confirmed on the Antarctic continent beyond the peninsula, but that doesn't mean H5N1 isn't there. Researchers have already observed unusual mortality among bird populations further east along the Princess Astrid Coast.

Along with the skua, crab-eater seals have been particularly affected by recent outbreaks. On Joinville island, where crab-eaters are common, the local population was devastated.

What about penguins?

One animal that hasn't been dying off is penguins. Both Adelie and Gentoo penguins have tested positive for the virus, but many infected individuals appear healthy. The virus is so thick in the air at their colonies that the researchers detected it using an air pump.

There were some suspicious penguin die-offs last year, which researchers think may have given the surviving birds immunity.

This is good news for penguins but presents a substantial risk to human visitors. Avian flu can infect humans who come in contact with infected birds. Of all Antarctic birds, the cute and friendly penguin is most likely to approach, or be approached, by humans.

The Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research (SCAR) established the Antarctic Wildlife Health Network database to monitor the spread. According to SCAR President Yeadong Kim, they are "deeply concerned with the evolving situation" in Antarctica.

With the fall of Antarctica, Australia is now the only uninfected continent.

Perched 44 meters up in a Jeffrey pine tree in California, two bald eagles have become the stars of a live-streamed saga. Earlier this week, the pair -- nicknamed Jackie and Shadow -- became new parents to two tiny eaglets while thousands of people tuned in to watch.

The non-profit Friends of Big Bear Valley (FBBV) installed high-definition cameras near the eagles' nest to give an unfiltered view into their world. Positioned discreetly to avoid any disturbance, these cameras operate around the clock.

Jackie and Shadow's journey has been anything but smooth. In previous years, viewers have watched ravens scavenge their eggs and harsh weather conditions thwart their breeding efforts. In both 2023 and 2024, Jackie laid eggs but they didn't hatch. Despite these setbacks, the pair rebuilds their nest for each breeding season, and every year, more viewers tune in.

Jackie has laid three eggs for the second year in a row, shocking experts.

“I’m very excited and a little bit surprised,” Sandy Steers, executive director of Friends of Big Bear Valley, told the Los Angeles Times. "Last year, it happened for the first time, and it’s so rare to have her lay three eggs again."

Since early March, viewers have waited impatiently to see if any of the eggs will hatch. In general, only 50% of bald eagle eggs hatch. This is often due to the high altitude, low oxygen, and cold temperatures. This year, Jackie and Shadow beat the odds.

Cracks appear

Cracks started to appear in one of the eggs on March 2. Although it's been three years since her last chick, Jackie immediately knew what was happening.

“Jackie was obviously feeling the movement underneath her as she kept looking down and standing up to roll the eggs much more than usual," said the FBBV in a statement. "Shadow happily got a turn on the eggs to give Jackie a morning break.”

The first eaglet emerged on March 3, and the second poked its head out through the eggshell on March 4. The live stream captured these moments in real time, allowing thousands of viewers to share the joy.

In an unbelievable turn of events, cracks started showing on the third egg on March 6. Hatching is not the quick process most imagine it to be. It can take a few days for a hatchling to fully make it out of the shell. Everyone is now waiting with bated breath to see if the third eaglet will hatch.

Next time you’re thinking about pond swimming, look for signs of beavers. A new study shows that these industrious rodents improve water quality, making wild swimming safer.

Among nature’s best engineers, beavers build dams that slow the flow of water and create small pools. These dams act as natural filters. They trap pollutants and keep harmful agricultural runoff out of our waterways. Stillwater pools allow sediment and pollutants to settle rather than flow downstream, significantly reducing harmful chemicals in the water.

"These ponds act as natural traps for pollutants and silt, especially when muddy or contaminated water flows in from upstream," co-author Nigel Willby told The Times. "[This] benefits downstream ecosystems."

The University of Stirling study found that water passing through areas inhabited by beavers had fewer pollutants compared to those without. Their dams cut pollution by up to 95%. This is particularly good news for wild swimmers, who risk infections and illnesses when dipping into contaminated water.

A cheap and simple solution

Agricultural pollution is an ongoing issue across the UK. Pesticides, fertilizers, and sewage often pour into rivers, destroying many once-popular wild swimming spots. Beavers might be the most cost-effective solution to this issue. Their dams require no maintenance and work around the clock. The reintroduction of beavers in certain areas has already shown very promising results.

Fishing enthusiasts also benefit from their presence since cleaner water means healthier fish populations. Often, excessive nutrients from agricultural runoff cause algal blooms on the surface of the water. This blocks the sunlight from aquatic plants, depleting the oxygen in the water and eventually suffocating underwater life.

Many conservationists are arguing for reintroducing beavers to more rivers and lakes. Some landowners worry that the dams may cause local flooding, but the overall benefits outweigh the drawbacks.

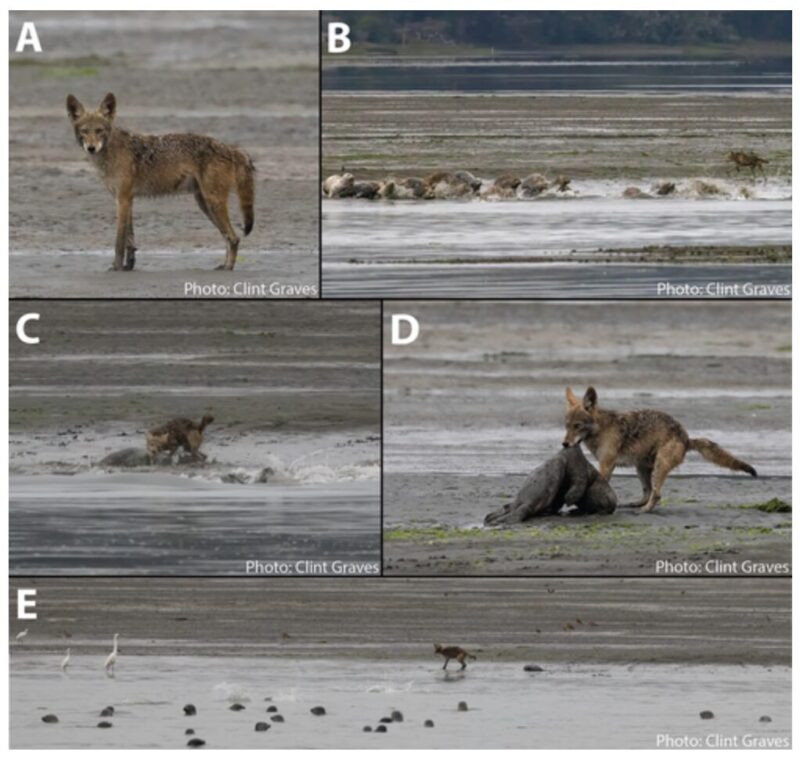

Coyotes will scavenge from bins, hunt small vertebrates, and chow down on pretty much anything. But now we can add something new to their list of favorite meals. For the first time, scientists have captured footage of coyotes hunting harbor seals.

We know that land carnivores hunt marine mammals. It happens on coastlines around the world. On Canada's Ellesmere Island, arctic wolves occasionally prowl cracks in the sea ice, looking for sunbathing seals. But little is known about how common such interactions are.

In the last few years, Sarah Grimes, co-author of the new study, had noticed seal-pup carcasses on MacKerricher State Beach in California. Weirdly, they had all been dragged to almost the exact same spot and then eaten. What predator was devouring the pups was a mystery. Black bears, bobcats, mountain lions, and coyotes all stalk the region. Based on nearby tracks and droppings, Grimes had suspected coyotes but never had any proof.

Caught on camera

Then in 2023-24, the motion-trigger cameras recorded coyotes dragging the seals away from the beach on three separate occasions.

Since the new study, other researchers have come forward with photos of coyotes hunting seal pups elsewhere in California, as well as in Washington State and Massachusetts.

These are not simply opportunistic attacks. Most of the time, the coyotes start by eating the brain, tearing off the baby seals' heads to get to it. Between 2016 and 2023 scientists discovered the remains of over 50 pups that had been dragged away from the rookery on MacKerricher State Beach to nearby dunes and eaten this way.

Historically, seals in the area raised their pups on the islands. As the numbers of wolves and grizzlies fell in California in modern times, some seals moved to the mainland. In recent years, more seals are choosing rocky, hard-to-reach areas rather than more accessible beaches. It seems that the presence of land predators influences where seals raise their young.

The team is now interested in seeing if this coyote behavior also occurs at other seal rookeries.

Frankie Gerraty, lead author of the study, has long studied coyotes and worries this will only put people off coyotes even more.

“Coyotes have a PR problem,” he says. “A lot of people do not like coyotes, but everybody loves baby seals.”

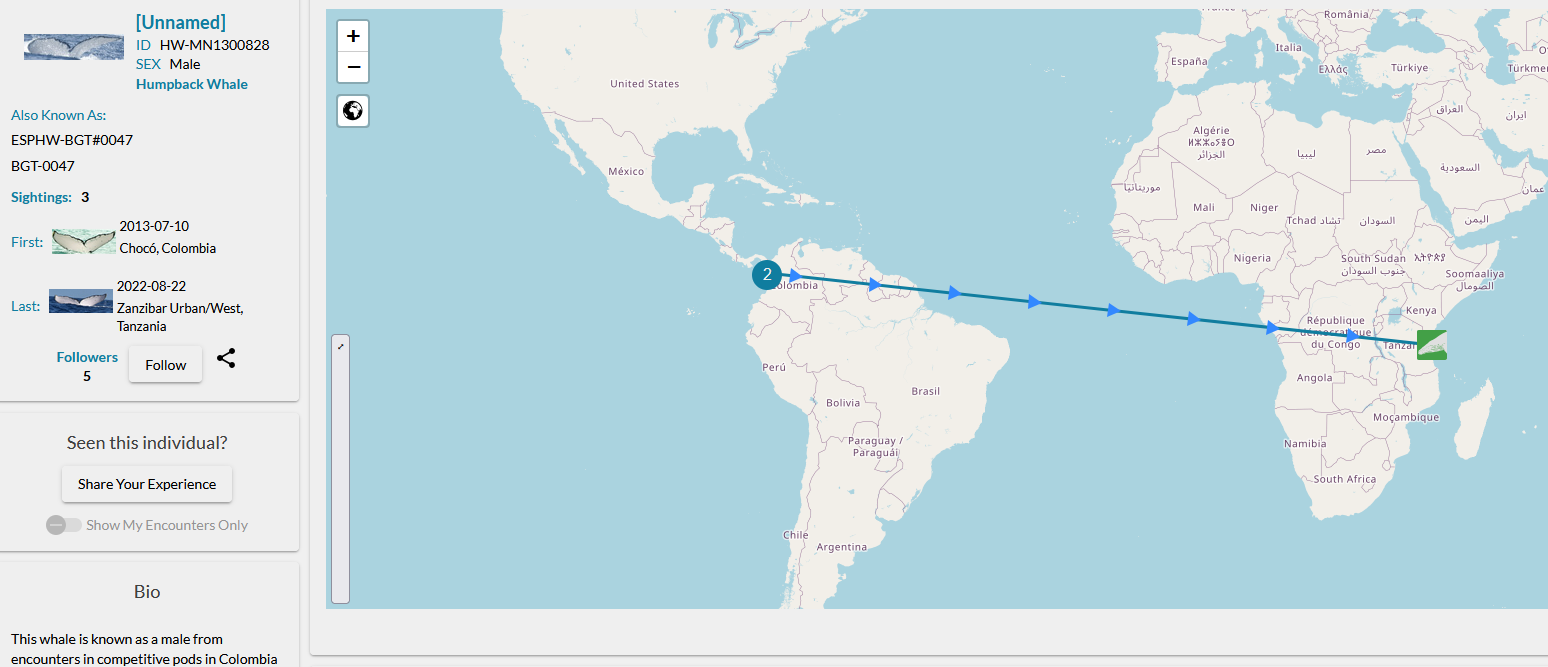

A young Venezuelan packrafter briefly became a modern-day Jonah and Pinocchio when he found himself inside the mouth of a humpback whale. The whale released Adrian Simancas unharmed, and his father, Dall Simancas, caught the entire bizarre incident on video.

Adrian Simancas, 23, and his father Dall, 49, were packrafting through the Strait of Magellan between Tierra del Fuego and mainland South America. Dall, who’d been filming the waves, had his camera trained on his son when two massive jaws emerged from the water and closed around the little yellow inflatable and its lone passenger.

For a moment, the choppy waters are empty, with man, beast, and boat submerged beneath the waves. Then, Adrian reemerges, followed by the packraft, which he quickly swims for. A massive grey, finned back crests briefly beside him and then is gone.

Amazed at his lucky escape, Adrian later described his experience. The inside of the whale’s mouth, he said, was slimy against his face, and all he saw was dark blue and white. He thought he was going to die -- and then he was on the surface again, pulled up by his life vest.

Not technically swallowed

Despite thousands of years of mythology, it is not actually possible for a person to find themselves in the stomach of a whale.

"Ultimately, the whale spit out the kayak because it was physically impossible to swallow," said Brazilian conservationist Roched Jacobson Seba.

Despite their massive size, whales have very narrow throats, about the width of a human fist. They can stretch to be a bit larger, up to about 38cm, but a boat and its passenger are quite beyond their capabilities.

Only one whale can theoretically swallow a human. The sperm whale has sharp teeth and feeds on large squids and fish. This means it has a large enough esophagus to gulp down a human. Encounters with them are much rarer, though, and sperm whales have not swallowed any humans except in fiction. The leviathan in Moby Dick that nipped off Captain Ahab's leg was a sperm whale.

Being engulfed in the massive mouth of a humpback, however, is not off the table, as Simancas learned. He isn’t the first person to spend time in the slimy maw of a whale. In 2021, a humpback 'swallowed' lobster diver Michael Packard off Cape Cod. Like Simancas, he was soon spat back out. Californian kayakers in 2020 and a tour operator off South Africa’s Port Elizabeth in 2019 reported similar incidents. This even once happened to a confused harbor seal.

Probably unintentional

Researchers have weighed in on these engulfing incidents. They insist that the whales did not intend to have people in their mouths any more than the people intended to be there.

As baleen whales, humpbacks take in huge gulps of seawater. Then they use the bristles in their mouths to filter for plankton, shrimp, and small fish. This is what they are after, and the rest, like paddlers, they soundly reject. When you are as big as a whale and maybe not paying attention, you can accidentally gulp down Adrian Simancas and his packraft along with your seawater and shrimps.

Accidents like these are why whale researchers warn people not to use silent craft, like kayaks and paddleboards, in waters where whales are active. Whale-watching boats keep their engines on at all times to alert the whales to their presence.

Adrian Simancas and his father don’t hold a grudge against the whale. At first, terrified, Adrian thought an orca was eating him. However, after he got free, he realized that the whale was probably “just curious.” Father and son said they plan to get back in the water soon, despite the engulfing.

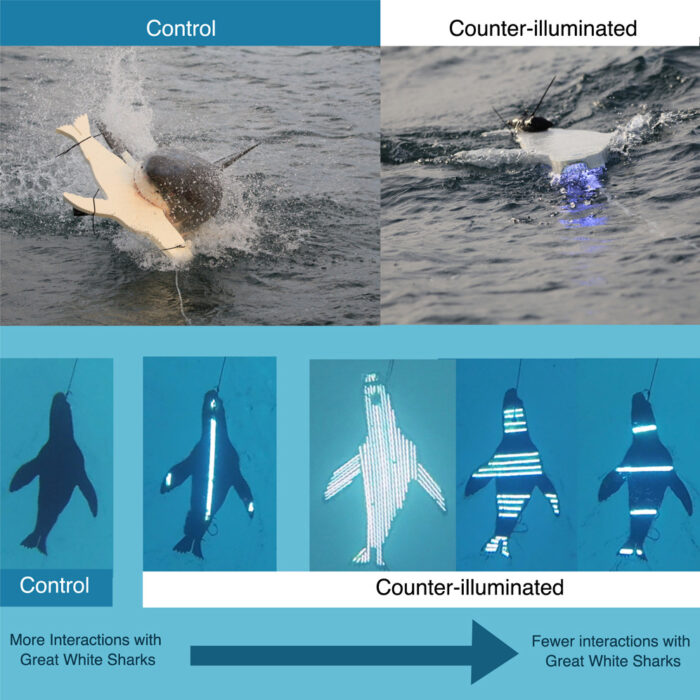

There is good news for anyone afraid of sharks. Last year, there were only 47 unprovoked shark attacks, a 28-year low. The annual average over the last decade has been 70 a year.

The Florida Museum of Natural History pulls together the International Shark Attack File (ISAF) annually. This is perhaps not surprising since Florida has the highest number of unprovoked bites worldwide. Of the 47 attacks, 14 occurred in the Sunshine State. Eight of those were from a single county, Volusia, in the northeast part of the state.

Florida has more shark attacks per year than the second, third, fourth, fifth, and sixth countries on the list combined. This is likely due to the number of juvenile sharks in the area. It is also a known breeding ground for blacktip sharks.

“Some years see an increase in bites, followed by periods of decline in what appears to be a random cycle," ISAF’s Joe Miguez told CNN. "Because of this natural variability, we cannot attribute this year’s decline to any single cause.”

For an attack to make the list, the victims must not have initiated any contact with the animals. This includes situations where they are actually trying to help the sharks, such as disentangling them from fishing nets.

Only four fatalities

Swimmers and waders were the victims of half of all shark attacks in 2024. Surfers came next at 34%, and then snorkelers and free divers at 8%.

Of the 47 bites, only four were fatal. Actor Tamayo Perry died surfing in Hawaii, and three tourist fatalities occurred in Egypt, the Maldives, and international waters near the Western Sahara.

What is always clear from this yearly data is that the risk of being bitten by a shark is almost zero. The odds sit at about one in 28 million. You are more likely to be killed by lightning.

“The fact that numbers are even lower than last year reinforces the idea that humans aren’t natural prey or even likely targets for sharks,” said Neil Hammerschlag of the Shark Research Foundation.

The ISAF's top tips for staying safe include avoiding going into the ocean at night, dawn, or dusk. Sharks are harder to see and more likely to be feeding. You should also remove jewelry, which can resemble fish scales when light reflects off them.

While filming the BBC Winterwatch television series in Northern Ireland, the crew discovered a dead body.

It was a spider’s dead body, which is not nearly as alarming as other types of corpses, but it nevertheless presented a rather creepy mystery.

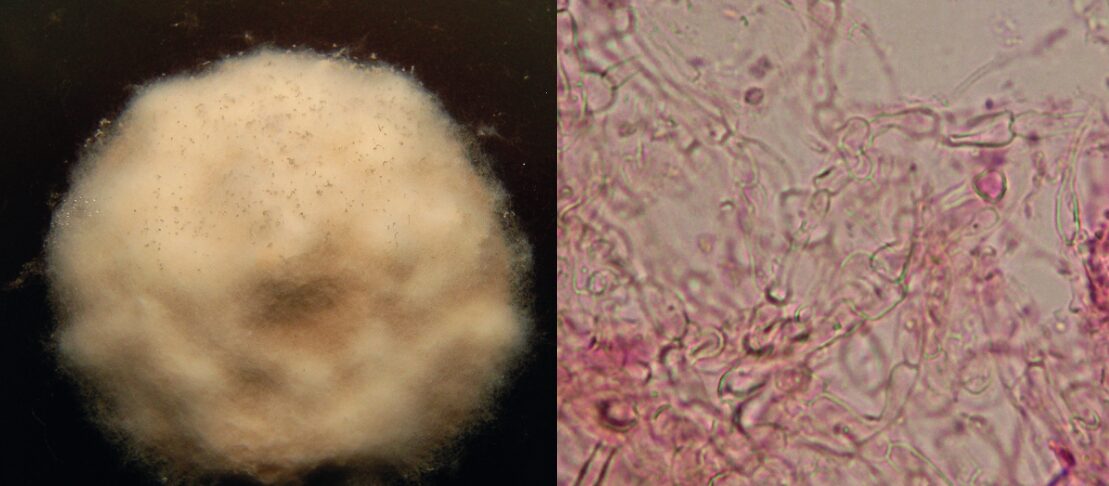

The spider was an orb-weaving cave spider, Metellina merianae, found deceased on the ceiling of an abandoned Victorian gunpowder store. A strange location for the reclusive, cave-dwelling spider, but even stranger was the condition of the body.

A crystal-like whitish growth entirely covered the victim's body, with only the legs sticking out from the pale and jagged fungal mass. Intrigued, the crew photographed the fungus and the spider it had consumed.

They sent the photos and the specimen to Dr. Harry Evans, an expert in fungi. He received the body, which had been carefully air dried in a sterile plastic tube, and set to examining it. A new article reveals the results of his investigation: They had found a new fungi species, one that infected and took over the bodies of spiders.

An accidental Victorian import?

Genetic analysis backed up Dr. Evans’ initial observations. His colleague at the Centre for Agriculture and Biosciences International, microbiologist Dr. Alan Buddie, sequenced the DNA of the new fungus. He confirmed that it was a unique species of the genus Gibellula and sketched out an evolutionary tree.

The phylogenetic tree placed it in the same family as two species of fungus from Asia. leading to speculation about its origin. Paul Stewart, Manager of Castle Espie, where the gunpowder store is located, proposed that it had come from Asia. During the 19th century, the British Isles engaged in a brisk trade with Asian markets. Could this fungus have entered Ireland over a century ago on gunpowder packaging and flourished in the dark, damp storeroom?

They needed more samples. An Irish caving specialist named Tim Fogg entered two different cave systems in Northern Ireland armed with delicate forceps and sterile collection tubes. He carefully noted the spiders’ locations and then sent them on to researchers. The fungus was present, which confirmed that it had not been imported in the 19th century but had been in Ireland for far longer than that.

Gibellula attenboroughii

At first, the new fungus was humorously known as Gibellula Bangbangus, in honor of the gunpowder storeroom. But ultimately, it received a new name, Gibellula attenboroughii, after legendary BBC presenter Sir David Attenborough. Without his work, the nature program that found the fungus would likely never have existed.

This is not the first species named after David Attenborough. Previous examples include a Peruvian frog, a long-beaked echidna, an Indonesian weevil, and a tiny marsupial from Australia’s early Miocene.

The fungus is certainly novel in other ways, however. It doesn’t just grow on its hosts, the cave-dwelling Irish orb-weaver, and its close relatives. It also controls them. Once infected, the spiders were swallowed up by a mass of fungus, growing out in thin tendrils and spikes. The fungus then changed the behavior of the hosts in order to propagate itself.

Usually a reclusive creature hiding in dark corners and waiting for prey, the cave spiders were forced to move, minds and bodies overcome by the invader. They were driven out into the open and allowed to die. The fungus then began releasing spores into the open air.

More zombifying fungi out there

The spiders were found dead on open ceilings and cave walls and even, perhaps, on a patch of moss beside a Welsh lake. A dead Metellina merianae spider turned up on the shore of Lake Vyrnwy in Wales in 2016, covered in fungus and exposed to the open air. Researchers now believe this, too, was Gibellula attenboroughii.

The spider fungus of the British Isles, the new study argues, has been long neglected. This new discovery shows that more work is needed to understand the variety and extent of the fungal infections in British and Irish spider populations. Spiders are key to the ecosystem, and so their health is vitally important. Especially since more undiscovered Gibellula species likely exist.

Perhaps the most intriguing question to pursue, however, is how the fungus works. The fungal infection forces the spiders out into the open, but it isn’t clear how it does so. The infamous cordyceps fungus, which infects and controls Amazonian ants, works by taking control of the body, leaving the mind terrifyingly unaltered. Is this what is happening to scores of shy Irish orb-weavers? Is the fungus triggering hormonal changes that alter behavior?

We are left with unknowns. How are the spiders being controlled? Perhaps more importantly, just how widespread are these understudied arachnid fungi? For now, we can only be grateful not to be orb-weaving cave spiders.

Two thousand kilometers from the southern tip of South America sits the island of South Georgia, a Yosemite-sized piece of polar tundra boasting thriving communities of king penguins, elephant seals, and fur seals. Alongside this charismatic fauna, native birds like the South Georgia pintail duck and Antarctica's only songbird, the South Georgia pipit, coexist. And here, in 2021, Belgian nature photographer Yves Adams caught a striking yellow-gold penguin on camera.

Where normal penguins had black feathers, this one had neon yellow. The effect was probably caused by leucism, a genetic mutation that results in depigmentation. Because the penguin was never studied closely, though, it could also have been albino.

Mission yellow penguin

Yves Adams returned to South Georgia this year as an expedition guide, hoping to find his golden penguin once more. It was nowhere to be found.

But his expedition leader tipped him off to something even more extraordinary, Adams told IFLScience. Adams kept his eyes open, and his patience was eventually rewarded. In a flock of its peers stood a jet-black king penguin.

Besides the video above, Adams snapped a set of glamor shots of the penguin: standing solo, frolicking in the snow, and inspecting the ground with neck-elongating intensity.

Adam's black penguin is striking, but beyond that, it's also amazingly rare. In 2019, a National Geographic photographer snapped a shot of another black king penguin, this one with splashes of white on his wing. Partial melanism, when animals are mostly but not entirely black, is more common than complete melanism. Even for the 2019 penguin, an ornithologist made the journalist who contacted him swear an oath that the black penguin was real.

But Adams' new penguin isn't mostly black -- it's entirely black.

#blackoutpenguin

Up close, Adams said, the penguin's belly feathers have a greenish tint. He seemed healthy and fit in with the rest of the flock.

On Instagram, he wrote, "This one is for the penguin addicts!" In case the penguin addicts needed some help from the algorithm, he tagged the photos #gothicpenguin, #formalpenguin, and #blackoutpenguin.

The prize for his best hashtag, though, stays with his original golden penguin: #yellowpenguinlove. Well, just look at it -- it's yellow, and hard not to love.

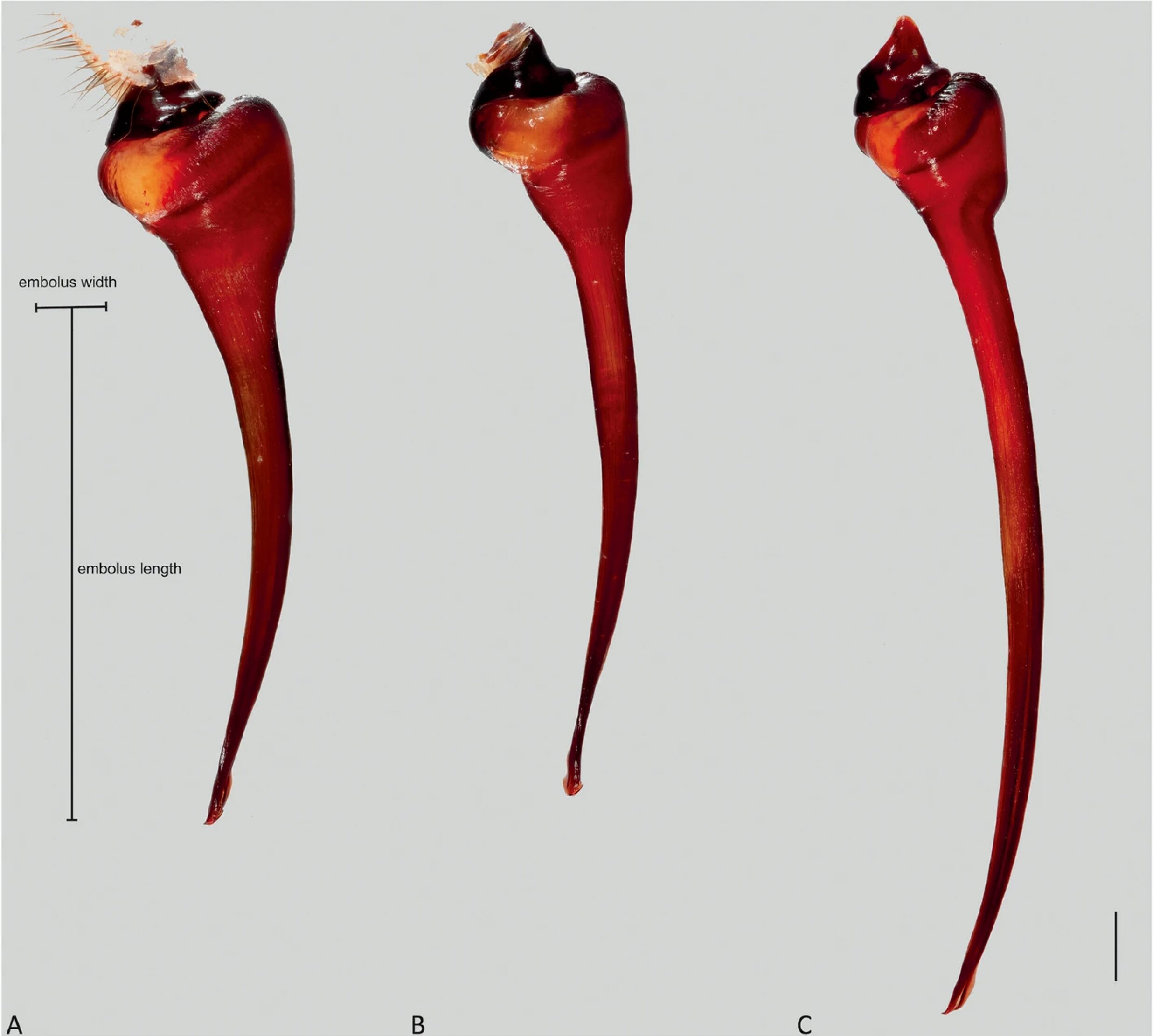

Australia has a reputation for venomous wildlife, particularly spiders. A good part of that reputation comes from the deadly Sydney funnel-web spider, Atrax robustus.

This particular spider has evaded easy categorization. Different specimens across its range vary widely in size and, crucially, the amount and deadliness of venom. But researchers have taken a closer look at this spider and discovered something unexpected: it isn’t a single species at all.

Venomous menace

First described by English clergyman and noted arachnologist Octavius Pickard-Cambridge in 1877, the Sydney funnel-web spider is responsible for over a dozen recorded deaths. It is considered the most venomous spider in the world. The venom is more potent in males, which are also more aggressive and tend to wander in the open after a rainfall. They also tend to hang on or bite multiple times once confronted.

The initial bite is painful, and symptoms set in quickly, within an hour of the bite. The Sydney funnel-web deploys a neurotoxic called Delta atracotoxin. This D-atracotoxin causes breathing difficulty, wild fluctuations in blood pressure, muscle twitches, vomiting, and nausea. Other symptoms include uncontrollable weeping, sweating and salivation.

Luckily, there is an antivenom. Since it was developed in 1981, there have been no recorded deaths from the Sydney funnel-web. Producing this antidote requires a large number of captive spiders, which researchers at the Australian Reptile Park carefully “milk” for their venom.

This program received a donation of one such spider in early 2024. When measured, this individual measured 7.9 centimeters or 3.1 inches from leg tip to leg tip. Named “Hercules,” he was the largest Sydney funnel-web spider ever recorded.

Actually, it turns out he isn’t. He’s an entirely new species.

A puzzling species

Massive specimens like Hercules and Colossus, the previous largest specimen, collected in 2018, raised questions for researchers. Why did the Sydney funnel-web vary so widely in size and lethality? Nearly 150 years after the species was first defined, it was time to look into this.

Researchers from the Australian Museum, Flinders University, and the Leibniz Institute in Germany collected several specimens, including the original holotype used to define the species in 1877. Then they carefully measured every part of the spiders, from fang length to internal genitalia.

They also performed genetic analysis on 57 of the specimens, testing for the degree of difference between different groups. They found three distinct clades, which matched the geographical distributions and physical differences they observed.

So the one species was actually three. They estimate that the spiders diverged from each other in the late Miocene, between 13 and 2 million years ago.

The 'Big Boys'

The “true” Sydney funnel-web, and the most common of the three, will remain Atrax robustus. A second mountain-dwelling variety is now officially Atrax montanus. The final, larger, more venomous species is officially the Atraz christenseni. Researchers are calling them “Big Boys.”

Big Boys have a small range: only the area surrounding and to the north of Newcastle. The Big Boys also tend to build more cryptic funnel webs, making their burrows harder to spot than those of their smaller and more common cousins. This and their limited distribution may be why they were not previously identified as a unique species.

This discovery isn’t just great news for fans of large, extremely venomous spiders. It may be important for developing antivenom. The new species differentiation will help make better antivenom and allow doctors to predict how serious a given bite will be.

Their exact haunts have not been made public, as their unusual size and limited distribution, so close to an urban area, may make them vulnerable to overexcited collectors. While the Big Boys may seem fearsome, researchers are already worried for them.

“Conservation measures may be warranted,” the study warns, in order to preserve the iconic Sydney funnel-web family.

In 2018, an orca mother made global news for her striking display of grief. Her young calf had died soon after birth, but she had refused to let go of her offspring. Instead, she pushed the body of her calf through the water, balancing it on her head for 17 days and 1,600 kilometers before she finally left its body behind.