While Egyptian kings and queens are the most famous examples of mummification, the practice wasn’t just for pharaohs. It expanded over time until everyone from the poor up were being preserved for eternity.

So, where are all the mummies? Well, unfortunately, 700 years of rich Europeans ate them. For their health, of course.

From a 12th-century translation error, a massive trade kicked off, depopulating the tombs of Egypt to populate European apothecaries -– and starting an underground market in fake mummy powder.

Bitumen and mūmiyah

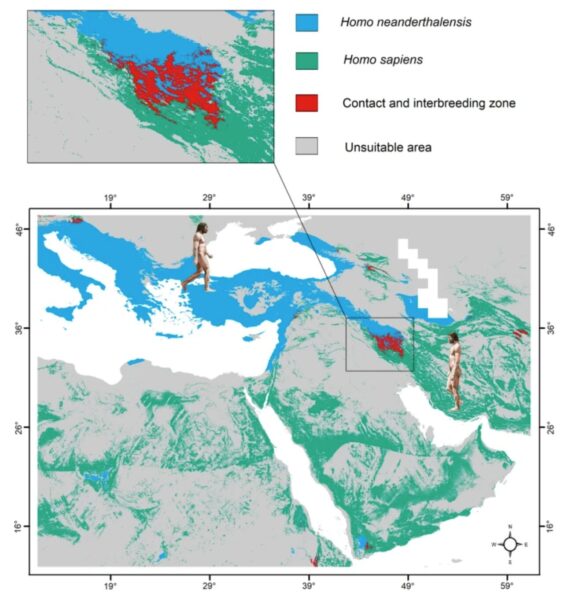

Why did Europeans think that eating mummies was a good idea? It's all to do with bitumen. Bitumen is a viscous petroleum product, which occurs naturally in a semi-solid form. Bitumen is particularly common around the Dead Sea, and is useful for waterproofing and as a glue. Archaeological evidence shows that both early humans and their Neanderthal cousins used bitumen tens of thousands of years ago. It even appears in the Bible as the mortar which was used in the tower of Babel.

By the classical era, bitumen was used in everything from shipbuilding to jewelry. People also started using it as medicine. Pliny the Elder, a Roman author and naturalist, lists 27 discrete medicinal applications for it. These include staunching blood flow, diagnosing epilepsy, treating leprosy, dysentery, and gout, and curing toothache.

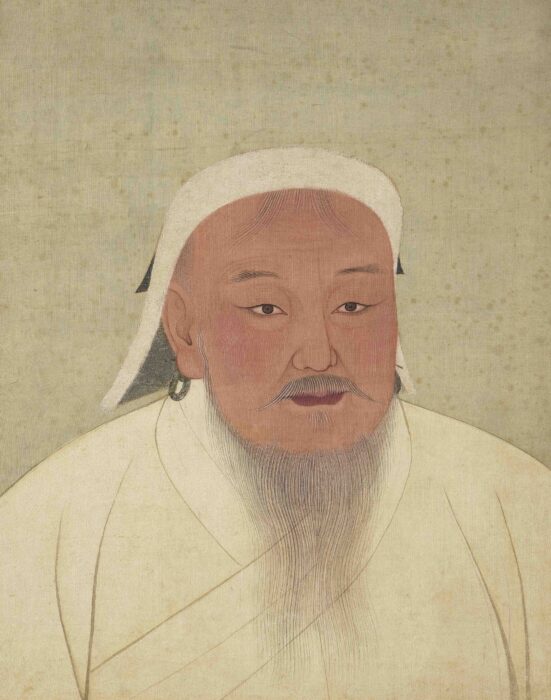

After the fall of the Roman Empire, Muslim scholars took pains to preserve classical learning. By the Middle Ages, Arabic authors were considered the foremost medicinal experts throughout Europe and the Middle East. The tradition of using bitumen as medicine continued through the works of scholars like Avicenna, who prescribed it for concussions, paralysis, and more. He didn't call it "bitumen," though. He called it mūmiyah, from the Persian word mum, meaning wax.

A medieval game of telephone

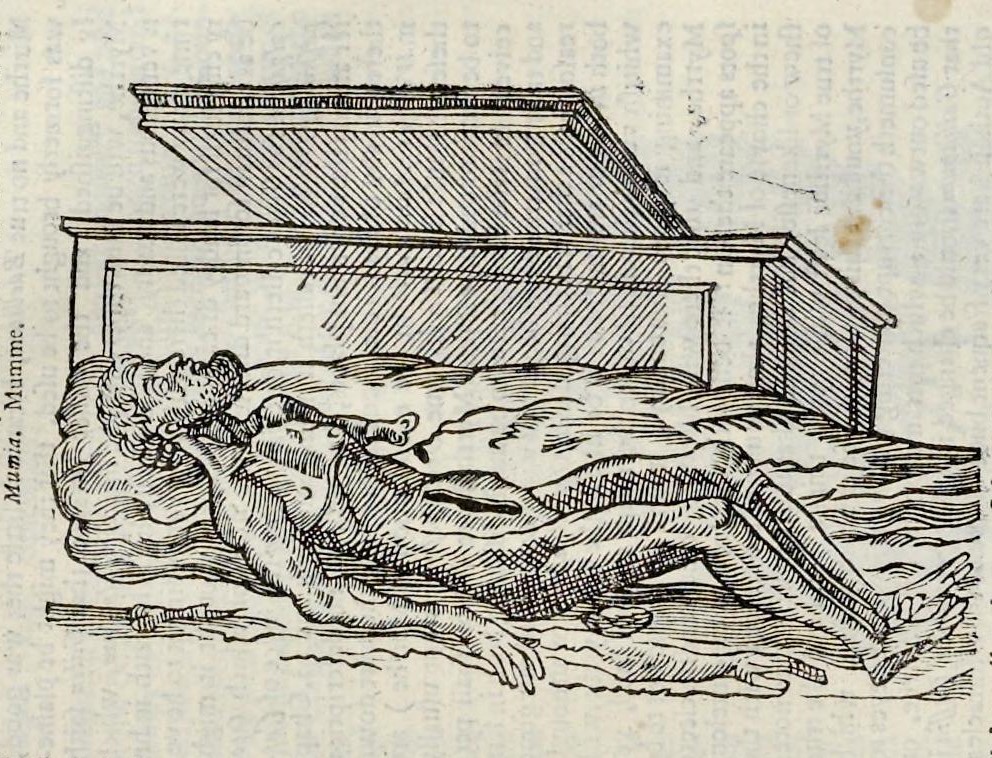

The Ancient Egyptians didn't use bitumen for their mummies. However, the dark resin they used resembled bitumen, leading many classical and medieval observers to believe that bitumen coated Egyptian mummies. So the same word came to refer both to naturally occurring bitumen and the dark waxy coating found on Egyptian mummies.

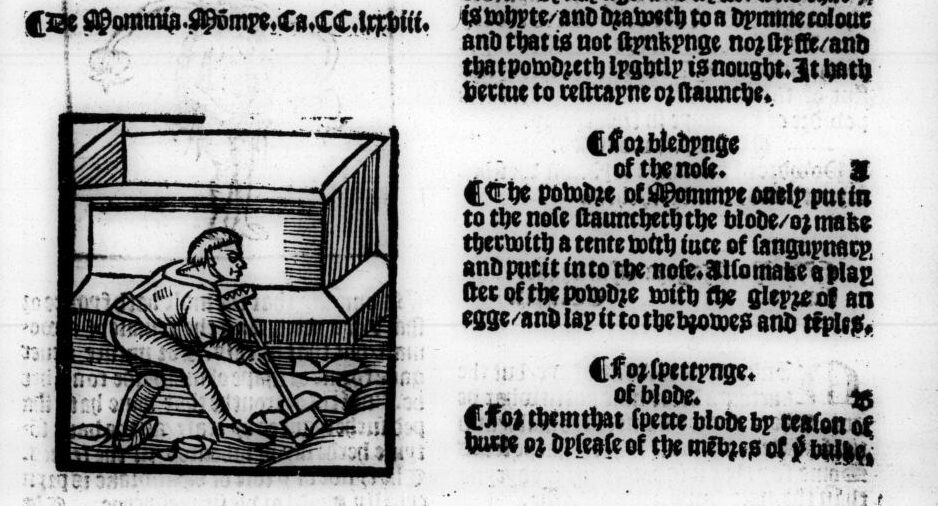

In the 12th century, an Italian translator of Arabic texts named Gerard of Cremona came across Rhazes of Baghdad's reference to mūmiyah. Gerard said the product was created when "the liquid of the dead, mixed with the aloes, is transformed and is similar to marine pitch.”

Another European, Simon Geneunsis, translated a work by Arab physician Serapion the Younger that referenced medicinal bitumen as "mumia." Geneunsis interprets the word along the same lines as Gerard of Cremona, calling it "the mumia of the sepulchers," which is formed when the aloes and spices used to prepare the dead mix with the liquids the corpse itself expels."

Meanwhile, crusaders were bringing back the bitumen medicine fad from the Islamic medical traditions of the Middle East. Unfortunately, the easily accessible supplies of bitumen in the area were limited. Shrewd Alexandrian merchants realized that there was all this mumia lying around, coating the bodies of the dead. They began raiding tombs, breaking the resinous bodies up, and exporting them to Europe.

The fact that the mumia came from corpses didn't bother people much, possibly due to the confusion between medical mumia and Egyptian mummies. Before long, mumia stopped being the substance on the mummy and became the mummy itself.

It's good for what ails you

Mumia became a wildly popular remedy in Europe, sold in every well-stocked apothecary. One influential pharmacopeia, Theatrum Botanicum, contains a long list of conditions mumia is useful for, including headaches, colds, coughs, seizures, heart problems, poisoning, scorpion stings, snake bites, bladder ulcers, paralysis, and retention of urine. Treatments involved combining mumia with other ingredients, usually a liquid like wine or goat milk.

Genoese physician Giovanni da Vigo considered mumia an essential medicine for ship's physicians and village doctors. He claimed it promoted wound healing and staunched bleeding. Sir Francis Bacon, the eminent English philosopher, and the physicist Robert Boyle, both considered it useful for wounds, falls, and bruises.

The French king, Francis I, was a habitual mummy consumer; contemporaries reported that he always carried a mixture of rhubarb and mumia on his person, just in case. Nicasius Le Febre, chemist to England's King Charles II, recommended mummy from Libya specifically.

By the way, if you were wondering how it tasted, the English College of Physicians has the answer. Mummy was listed in their official pharmacopeia from 1618 to 1747, where it is described as being "somewhat acrid and bitterish."

Supply chain issues

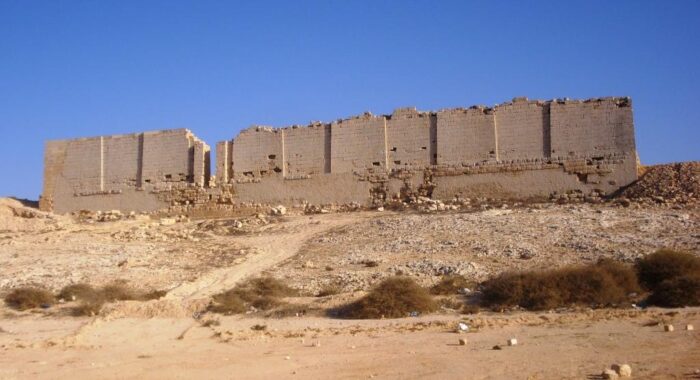

Egyptian authorities were not actually keen on all the grave robbing and corpse exporting that was happening. In 1428, authorities in Cairo captured and tortured several people connected to a mummy scheme. They confessed to robbing tombs, boiling the mummified bodies in a pot, and selling the oil which rose to the surface.

It was illegal to export Egyptian mummies out of Egypt. But enforcement could be lax, especially if you had money to grease the wheels. Englishman John Sanderson visited Egypt in 1586, where he explored a sepulcher and broke off chunks of blackened mummified flesh. He applied the correct bribes and compliments, and sailed off with 600 pounds worth of "divers heads, hands, arms, and feete."

For every literal boatload of real pillaged mummies, there was at least an equal measure of mummies created specifically for export. Many mummy sellers in Egypt found it was easier to source fresh corpses and dry them than it was to dig up old ones. These fresh corpses mostly came from executed criminals, plague victims, and enslaved people.

The Italian traveler Ludovico di Varthema wrote about the local production of mumia during a visit to the Arabian Peninsula. According to him, there were two kinds; the first was made from the dried-up remains of people who had died recently while crossing the desert. The other, nobler and more pure kind, was "the dryed and embalmed bodies of kynges and princes."

In truth, even authentic mumia wasn't made from rulers, but from their subjects. European nobles liked to imagine their healthful powder came from ancient priestesses and kings, but the remains of the poor were far more plentiful and accessible.

Paracelsus and domestic mummy manufacture

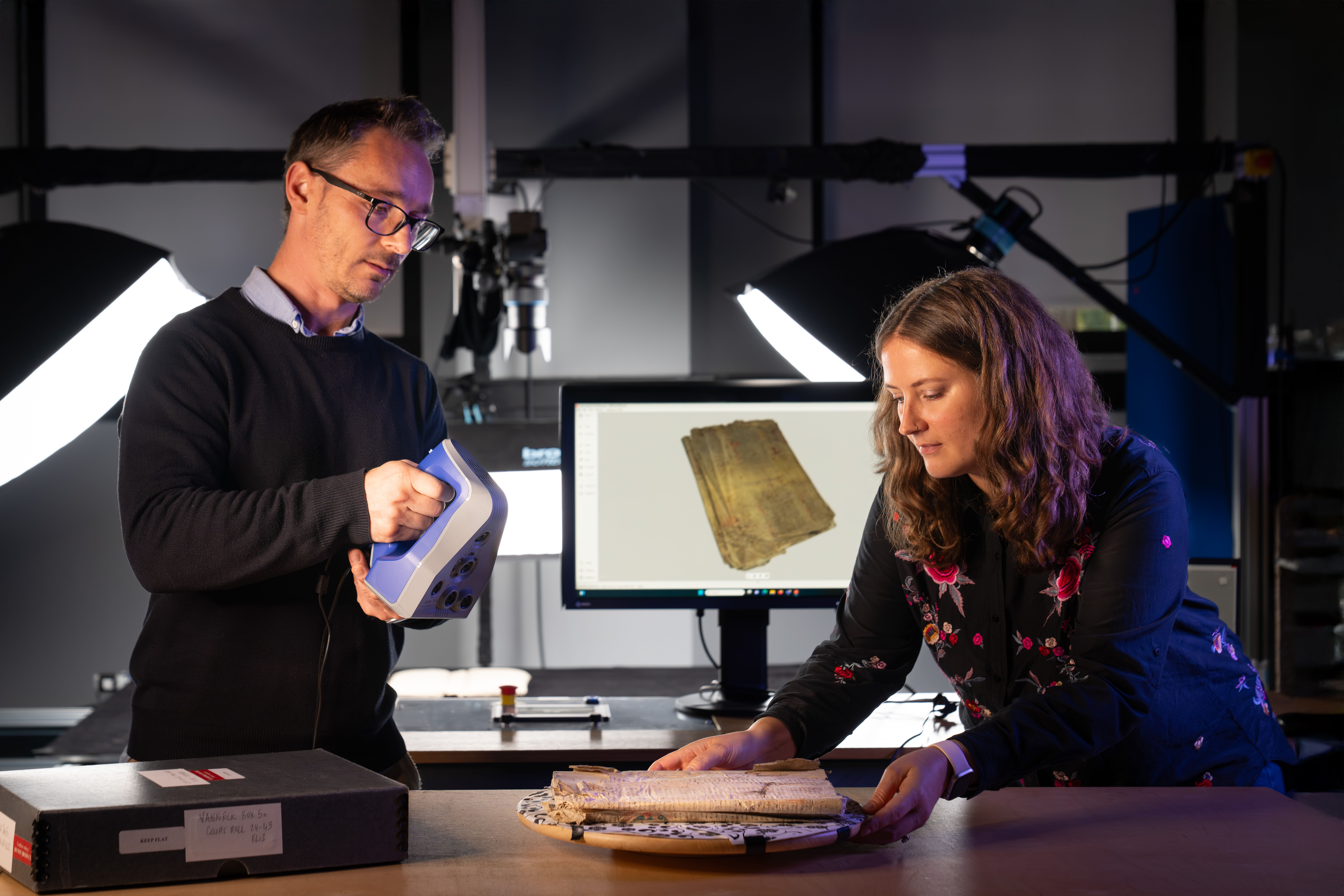

Though a fair amount of the mummy product on the market was inauthentic, the real stuff was still being sold into the modern era. One recent study analyzed the contents of an 18th-century pharmaceutical jar labelled "mumia." They found that the contents really were the remains of an Egyptian mummy from the Ptolemaic period.

But without our modern analysis tools, the question of mumia authenticity was an ongoing problem for physicians. As the supply became more questionable, some medical authorities began to wonder whether mumia being "authentically Egyptian" was even important.

Some definitions of mumia dropped the ancient Egyptian element entirely, ascribing benefits to any old preserved human flesh. The influential physician Paracelsus, who spawned a legion of followers, believed the medicinal benefit of mumia came from a transfer of life energy. To make his mumia, he left a fresh body out exposed. The best bodies were of young, healthy men who died suddenly. Other recipes in this line were even more specific, preferring a 24-year-old redheaded man who was recently executed.

There was a persistent belief that there was a vital animating force remaining in corpses, and one could benefit from this force by consuming corpse products. In the time of Paracelsus, for instance, executioners would collect and sell the blood of those they executed. People believed that drinking it promoted general health and cured epilepsy. Bandages soaked in human fat were applied to wounds, and powdered human skull was prescribed for headaches.

The broader genre of corpse medicine is beyond the scope of this article, but suffice it to say that mumia wasn't always the only human-derived medicine available.

Some reasonable concerns

Now I'm not a doctor, but I feel confident in saying that "you should eat powdered human corpses for nosebleeds" is not best practice. By the 16th century, many doctors were starting to think along the same lines.

Ambroise Pare, surgeon to four French kings, published a 1582 treatise decrying the use of mummy. He argued that most mummy sold was actually manufactured in France from the recently dead, and also didn't work. In his professional experience, it had not only failed to stop bleeding but had unsurprisingly caused the patient to have an upset stomach and bad breath.

Pare's German contemporary, Leonhart Fuchs, made similar arguments. He also laid out the series of medieval translation errors which had led to the idea of mumia. Fuchs decried the "stupid...credulity of certain doctors of our age," who still prescribed mummy.

Additionally, some commentators were beginning to recognize the historical and cultural wealth that was being ground up for tinctures. English natural philosopher Thomas Browne opined that "The Ægyptian Mummies, which Cambyses or time hath spared, avarice now consumeth. Mummy is become merchandise, Mizraim cures wounds, and Pharaoh is sold for balsams."

There was also cannibalism. Michel de Montaigne, a 16th-century French writer and early critic of colonialism, pointed out the hypocrisy of demonizing cannibalistic practices in the New World while taking medicinal human flesh at home. But most people didn't think of it as cannibalism, any more than people today would consider a blood transfusion cannibalism. Mumia wasn't food, it was medicine.

Still, as time went on, people were increasingly wondering if it was medicine they should be taking. Mumia mania peaked in the 18th century, but took much longer to fade entirely.

Consuming Egypt

For wealthy Europeans, part of the appeal of mumia was the mystical, exotic associations. For centuries, Europeans treated the bodies of deceased Egyptians with a combination of fetishistic fascination and blatant disrespect. They were curios and collectors' items, souvenirs of exciting trips turned household decor.

Mummy unwrapping parties were popular in 19th-century Europe, where middle and upper-class men and women would watch a mummy's bandages be unwound, revealing its body as the finale of the morbid show.

The remains were consumable as a variety of commercial products. A popular paint color from the mid-18th to 19th centuries was "mummy brown." This pigment was made from ground-up mummified bodies. Art historians believe this rich, warm brown pigment appears in a number of well-known paintings, including Eugene Delacroix's famous Liberty Leading the People. The last tube of mummy brown was produced, unbelievably, in 1964.

There are also accounts, of varying reliability, that both human and animal mummies were used as fertilizer, paper (from their bandages), and fuel for locomotives. These claims are likely exaggerated, but they speak to the manner in which mummified Egyptian remains were treated at the time. As Imperial plunder, they were, literally, things to be consumed.

The end of the mummy-eating era?

By the end of the Victorian period, mumia had fallen out of popular use. But it was still available for sale, and occasionally prescribed, into the beginning of the 20th century. The last known appearance of the drug for sale is in a 1908 Merck catalogue. The German pharmaceutical advertised, "Genuine Egyptian mummy as long as the supply lasts, 17 marks 50 per kilogram."

Rich old Europeans didn't actually eat up all the mummies. Archaeologists are still finding them, for one. It's impossible to say how significantly the manufacture of mumia impacted the number of surviving mummified remains. It's safe to say, though, that nearly a millennium of looting Egypt led to the loss of untold historical and cultural knowledge.

The 1908 example is troublingly recent, but we might still be tempted to dismiss mumia as something from another, less enlightened age. Exporting ground-up mummy to eat as a health supplement is something so patently absurd that a modern reader might make the mistake of smugly holding themselves above all those involved in the practice.

It's true that we don't eat mummies anymore. But physical and cultural wealth is still extracted from exploited nations for the consumption of the global north.

Most human bones available for sale in the West, as curios or medical teaching tools, come from India, though the export of human skeletons was officially banned in the 1980s. World-class museums still display cultural artifacts and remains of colonized people for the predominantly white public to gawk at. Mummy remains merchandise.

"Herds and flocks lie on verdant pastures

Wealth and splendor..."

More than a thousand years after it was last heard, a long-lost hymn to the ancient city of Babylon has been brought back to life, thanks to AI. This remarkable rediscovery gives us new insights into this ancient city.

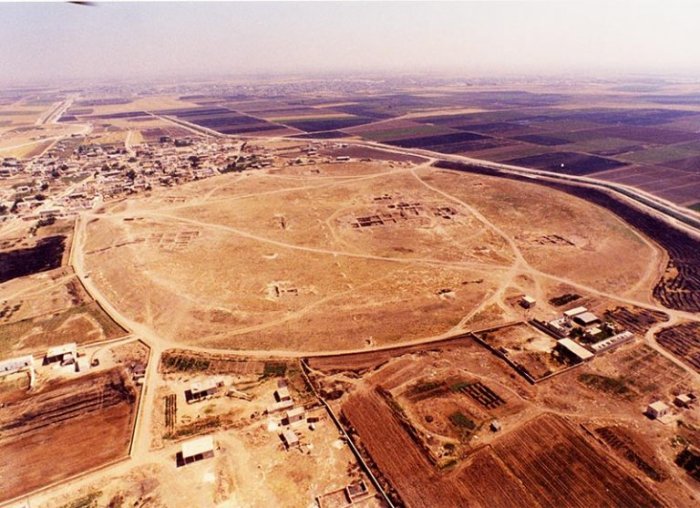

The hymn came from a collection of thousands of fragmented cuneiform tablets stored in the Sippar library in Iraq. The former city of Sippar lies about 70km from Babylon.

The breakthrough came when Professor Enrique Jimenez of Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich teamed up with researchers from the Electronic Babylonian Literature project. This aims to digitize text fragments from cuneiform tablets worldwide.

By the rivers of Babylon

In recent years, they have started using AI to analyze the ancient fragments and recognize patterns in the cuneiform writings. What emerged was a 1,000-year-old hymn devoted to the Mesopotamian city of Babylon. Babylon was founded around 2000 BCE and was once the largest city in the world.

“Using [AI], we managed to identify 30 other manuscripts that belong to the rediscovered hymn -– a process that would formerly have taken decades,” Jimenez said in a statement.

Legend tells us that Noah hid the city's library of cuneiform clay tablets in Sippar before the biblical flood. The newly rediscovered hymn praises the city and gives an insight into the daily lives of the people who lived there.

“The hymn was copied by children at school," said Jimenez. "It’s unusual that such a popular text in its day was unknown to us before now.”

Role of women

Another striking aspect of the 250-line hymn is the numerous references to the roles of women and priestesses and the tasks they performed in the city. No other cuneiform tablets have these references.

“This is the first time we have found such explicit details about the lives of Babylonian women, especially in priestly roles,” he said.

Mesopotamian writings typically focus on wars, royalty, and the gods of the ancient world. While the hymn does mention deities, it also highlights the beauty of the natural world and the farming lives of common people.

“It was written by a Babylonian who wanted to praise his city,” explained Jimenez. "The author describes the buildings in the city, but also how the waters of the Euphrates bring the spring and green the fields. This is all the more spectacular since surviving Mesopotamian literature is sparing in its descriptions of natural phenomena.

Researchers have shared a short translated excerpt of the hymn that describes the Euphrates River and its importance to the city on its river banks.

The Euphrates is her river — established by wise lord Nudimmud —

It quenches the lea [open land], saturates the canebrake,

Disgorges its waters into lagoon and sea,

Its fields burgeon with herbs and flowers,

Its meadows, in brilliant bloom, sprout barley,

From which, gathered, sheaves are stacked,

Herds and flocks lie on verdant pastures,

Wealth and splendor — what befit mankind —

About 30,000 years ago, humans arrived in Japan's southern Ryukyu Islands, 110km from Taiwan.

The archaeological record hasn't preserved any clues as to how these Paleolithic people made the crossing to this new land. But the obstacles to doing so seem, at first glance, insurmountable without modern technology and knowledge. So in 2013, a group of Japanese archaeologists set out to recreate the trip using only Paleolithic tools.

This week, they published the results of their experiments in the journal Science.

A challenging crossing

Archaeologists find evidence of humans in the Japanese archipelago as early as 35,000 BCE. Judging from the dates at different archaeological sites, the earliest inhabitants of Japan seem to have migrated both northward from Taiwan and southward from Korea.

But from the Taiwanese coast, the low-lying islands of Ryukyu sit below the horizon. One of the strongest currents in the world, called Kuroshio ("Black Tide"), runs northward from Taiwan. It carries any lackadaisical drifters west of the Ryukyu Islands at a velocity of one meter per second. And a distance of 110km from Taiwan to the nearest Ryukyu island, Yonaguni, was no joke for people without metalworking or sails.

Yet they made it.

When the Japanese archaeologists set out to recreate this trip, they didn't have an easy time. They tried reed-bundle rafts and bamboo rafts, both of which floundered in the strong current. The bamboo also began to crack and fill with seawater, further weighing it down.

The beginning of the voyage

In July of 2019, the team attempted one final trip. They launched Sugime, a hand-made dugout canoe, from the coast of Taiwan in typical calm summer weather.

Construction of the dugout started in 2017. The team used replicas of stone axes found in Japanese Paleolithic sites to fell a one-meter-thick Japanese cedar tree. They peeled off the bark and carved a seating area in the center of the trunk. While dugout canoes from the Paleolithic haven't survived in Japanese archaeological sites, dugouts from the later Jōmon period (starting around 14,000 BCE) boast burn marks on the inside. In turn, the team polished the inside of their craft with fire.

The plan was simple: to row from Wushibi, on the eastern coast of Taiwan, across the strait to the small Ryukyu island of Yonaguni. A motorized ship with safety supplies would escort the Paleolithic reenactors.

Sugime's crew consisted of five paddlers, four men and one woman. For the first hour and a half of their journey, they skidded over a calm sea, with only wispy clouds on the horizon. Then the water depth dropped, and they hit the edge of the Kuroshio. The wind slammed into the current, giving rise to choppy water and an ever-present swell as high as the side of their boat. One of the crew had to pause paddling to bail out the dugout over and over again.

They kept rowing into the night. The wind dropped slightly, but the dugout kept threatening to capsize in the strong swell. There was no rest that night, and it was a constant fight to keep the nose of the dugout pointing northeastward. As the water approached a flow of 1 m/s, the dugout pivoted northward along with the current.

Just as steering the boat was a challenge, so too was figuring out where to steer it. Clouds obscured the stars, and GPS wasn't an option in the Paleolithic. Only the direction of the swell indicated which way was north.

As midnight approached, the wind dropped and stars appeared. The paddlers took turns resting. But in the early hours of the morning, clouds once again obstructed the stars. At 3:40 am, while the captain was taking his rest, one crew member thought she saw dawn on the horizon. The crew pointed the dugout accordingly.

Then the captain woke up. The dugout was traveling due north, dragging them off course from their destination. He realized that far from being dawn, the light on the horizon was from the northern cities of Japan and was reflecting off the clouds. Sugime turned eastward once more.

Exhaustion and triumph

The next day dawned bright. Still unable to see their destination, Yonaguni Island, the crew kept paddling east-southeast to combat the current of the Kuroshio. Unbeknownst to them, however, they had left the Kuroshio behind them. They were now heading due east, away from Yonaguni.

They had already exhausted all the water they had packed for the voyage. Tired and thirsty, they called in a resupply. At noon, finding themselves in calmer waters and realizing they had left the Kuroshio, the whole crew slept for half an hour.

As they paddled into the afternoon, Yonaguni still failed to appear. They steered the dugout this way and that, hoping it would peek above the horizon. It didn't. Moreover, the crew was exhausted. Some of them jumped into the ocean to rest in the cool water. But nothing prevented the onset of excruciating muscle cramps and, as evening drew close, hallucinations.

Then, just before the sun set, a bird flew overhead. Before this, the sea had been lifeless and isolated. Now, land was near, even if they couldn't see it.

The sun was so intense that the food they had brought with them began to rot. They obtained replacements from the escort ship and ate a dinner of rice balls and noodles. As night slid in, the crew rested while the boat drifted loose on the water.

The captain kept watch. He thought he saw the glint of a lighthouse on the horizon that he hoped was from Yonaguni. As it turned out, it was an optical illusion, but the swell carried the dugout gently northeastward. In the early hours of the morning, the actual light from Yonaguni's lighthouse appeared on the horizon.

When the crew awoke in the dark hours before dawn, they began the final stretch of their journey toward it.

It was not until just after dawn on the third day that the crew finally saw Yonaguni Island. They were 20km from shore and had been rowing for over 40 hours.

Five hours later, they reached land. Since their crew included Taiwanese paddlers, they had to follow immigration protocol and land Sugime at a predetermined beach. Paleolithic explorers, presumably, did not have this restriction.

Piecing together a Paleolithic voyage

The crew had made it. Dugout canoes, unlike reed and bamboo rafts, can cross the Kuroshio. But at various points during the trip, the crew's mistakes had worked in their favor. When they rested, the swell naturally carried them in the right direction. And the first hint they saw of Yonaguni was from a lighthouse, which does not feature in Stone Age archaeological sites. Was their success a fluke?

To test this, the team used the data from their paddling to simulate hundreds of dugout voyages starting from different points in Taiwan. They used both modern and Paleolithic oceanographic models to approximate the flow of the Kuroshio, varying the strength of the current between ebbs and peaks. As long as the virtual boats paddled in the right direction, they made the crossing, even when the Kuroshio was at its strongest.

But the voyage could not be completed by accident. The Kuroshio does not carry mariners from Taiwan comfortably to the shores of Yonaguni. Paleolithic humans had to identify the direction and strength of the Kuroshio and plan their voyage accordingly.

They also had to know Yonaguni was there. From the coast of Taiwan, it is not visible. Only when one climbs the mountains in the north does the little speck of island appear over the horizon. The summit of the highest of these mountains sits at nearly 4,000m.

This research in experimental archaeology shows that inhabitants of Taiwan 30,000 years ago did not drift aimlessly towards the Ryukyu Islands. They climbed mountains, they built sturdy boats, and they knew how to chart a course against one of the strongest currents in the world.

Deep in the northern Ontario bush, there is a stone covered in strange markings. No one knew it existed until a tree fell over and exposed it. Carved into the slab of rock are a series of ancient runes that archaeologists have been trying to decipher for years.

The stone was found in 2018, and pictures of it were quickly sent to Ryan Primrose, the director of the Ontario Centre of Archaeological Education.

“It's certainly among the least expected finds that I think I've encountered during my career. It's absolutely fascinating," he told the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation.

Primrose was worried people would assume that the markings on the stone slab were created by Vikings, so he has been quietly working on the mystery for seven years.

"We didn't want to release information publicly until we had done as much as we could at the time to understand exactly what it was," he said.

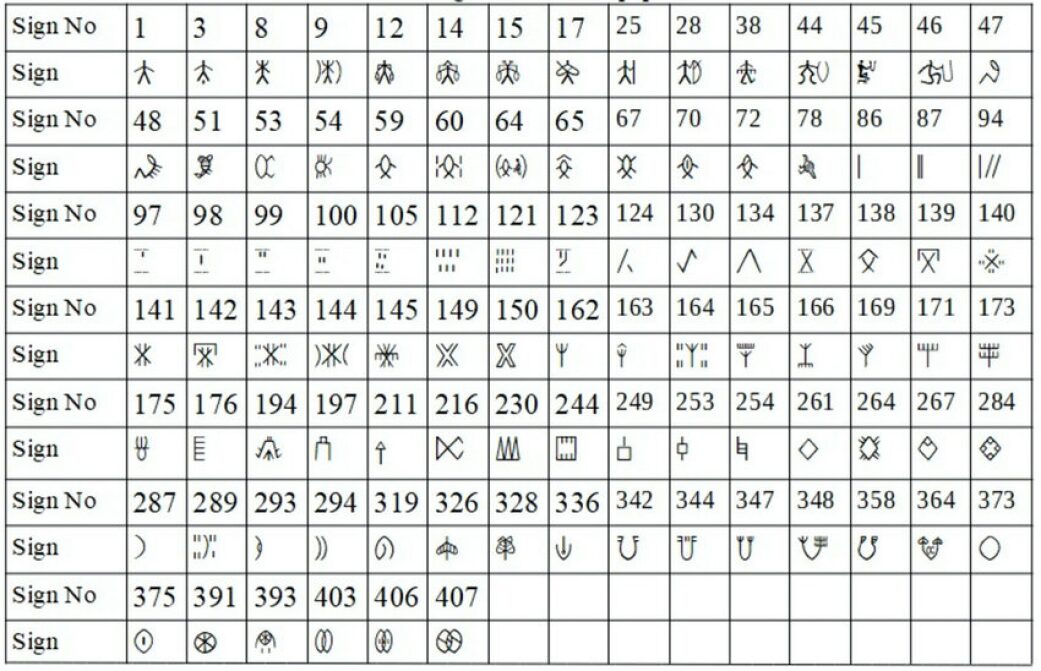

The stone slab, about the size of a small tabletop, is half-buried in the rocky ground. From a distance, it looks as though it is covered in scratches. It is actually a series of 255 runes alongside an illustration of a boat and 16 further runic symbols that have been purposefully carved into the rock.

Primrose decided to bring in runology expert Henrik Williams. He flew over from Sweden and sat under a tarpaulin for three hours with a flashlight, looking at the runes. He realized the symbols were Futhark alphabet runes, which were originally used in Scandinavia.

A confusing timeline

Etched into the bedrock is an early Swedish rune version of The Lord’s Prayer. The prayer can be traced back to 1611. This initially caused confusion. There were no Swedes in the region at that time, so who could possibly have carved this into the rock? But the prayer was republished in the 19th century, and at that time, the Hudson’s Bay Company did employ some Swedes. They had a trading post in Michipicoten, which is relatively close to the runes.

There is no way to know exactly how the carvings came to be, but Primrose and William reasonably think that someone working for the Hudson’s Bay Company is responsible. Etching all 255 runes into the rock is a task that would have taken days or weeks. Once created, they believe it might have been a central point for religious prayer or for Swedes to come together.

This timeline means that the stone is much newer than many would assume. Researchers estimate that it was carved around 1800. The team admitted they were a little disappointed to discover that the runes were not older.

The deepest shipwreck ever found in French waters has been discovered in the Mediterranean off southern France. The 16th-century merchant ship lies an astounding 2,567m down.

The French Navy stumbled across the wreck in March 2025, south of Saint-Tropez, during a routine seabed mapping mission. When the drone's sonar picked up an unusually large structure, the curious operators sent down a remotely operated vehicle to investigate. What it captured was incredible -- the remains of a wooden ship that has laid untouched for centuries.

The wreck, now called Camarat 4, is a Renaissance merchant vessel, roughly 30 meters long by 7 meters wide. Experts believe it sailed from Italy, loaded with ceramics, cookware, and metal bars. Images show around 200 glazed ceramic jugs, 100 yellow plates, two cauldrons, and six cannons among the wreckage.

Many of the jugs bear the monogram “IHS” etched into them, the first letters of the Greek name for Jesus, or are adorned with geometric and plant-based patterns. The detailing on the jugs suggests they came from the Liguria region in Italy.

Frozen in time

Marine archaeologist Marine Sadania, who is part of the team leading the study, described the wreck as “frozen in time.” Its depth has kept it almost perfectly intact, preventing looting of any of the items. As a result, it offers an incredibly rare window into Renaissance maritime trade and shipbuilding.

This shipwreck now holds the record as France’s deepest ever discovered, surpassing the previous title holder, the submarine La Minerve, found in 2019 at 2,300m down.

Researchers plan to digitally map and study the wreck. Using high-resolution photography, they are building a complete 3D model of the site that will capture every detail, from the woodwork to the ceramic decorations. Robotic arms will recover a few select objects to gain a fuller picture of life aboard the ship; the rest will remain in place.

It seems that people 1,700 years ago enjoyed the same battles of endurance that you might find today in a country pub. Archaeologists have uncovered a marble sarcophagus from the Roman era in Caesarea, Israel. Haut-relief sculptures on the sarcophagus show a wine-drinking contest between Dionysus, the Greek god of wine, and the legendary Roman hero, Hercules.

A joint team from the Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA) and the Caesarea Development Corporation found the sarcophagus buried beneath a sand dune outside the city’s ancient walls. Excavation leaders Nohar Shahar and Shani Amit described the discovery as something out of a movie.

“We began brushing away the light sand of the dune when the tip of a marble object suddenly emerged,” they recalled. “The whole team gathered around, and as we cleared more sand, we could hardly believe what we were seeing.”

A defeated Hercules

A main panel shows a defeated Hercules clutching a cup and apparently unable to stay upright. Meanwhile, a victorious Dionysus celebrates with an entourage of mythological creatures and revelers.

Researchers believe the scene represents more than a mythological boys' contest, that it symbolizes the soul’s passage from the physical world to the afterlife.

“The figures are not only celebrating, they are accompanying the dead on their last journey, when drinking and dancing are transformed into a symbol of liberation and transition to life in the next world,” said Shahar.

Shahar also noted that this is the first time archaeologists have found the Dionysus-Hercules wine contest depicted on a burial coffin in the region. Similar scenes appeared in the 2nd and 3rd centuries, but they were typically found in mosaics, not sculpture.

Although discovered in Israel, the artists likely used marble quarried from northwestern Turkey, since there were no local marble quarries in ancient Israel. Archaeologists think that the piece was created in Turkey, with some final details added after it arrived in Israel. The elaborate design and imported materials make it very clear that a wealthy family that “enjoyed a certain lifestyle" commissioned it "as a fitting reflection of their identity.”

Researchers have finally confirmed that a long-sunken hulk off the coast of Colombia is none other than the San José. The legendary Spanish galleon, which vanished beneath the waves of the Caribbean 300 years ago, has been dubbed the “world’s richest shipwreck.” Now the big question is, who does the treasure belong to?

The San José was first launched in 1698 and was the flagship of the Spanish treasure fleet. In 1708, it was carrying gold and jewels from Peru to Spain that would help fund the War of Spanish Succession. As the ship approached Cartagena, Colombia, British naval forces attacked. During the melee, the gunpowder stores on the San José ignited, sinking the ship. Nearly 600 crew members perished as the ship went down with its vast cargo of gold, silver, emeralds, pearls, and other treasures.

For centuries, the wreck remained lost beneath the sea. Two groups claim they discovered the famous shipwreck. U.S. salvage company Glocca Morra (now Sea Search Armada) insists that it first found the location of the ship in 1981. Then, in 2015, the Colombian navy, working with marine archaeologists, located the actual remains of the galleon using underwater drones.

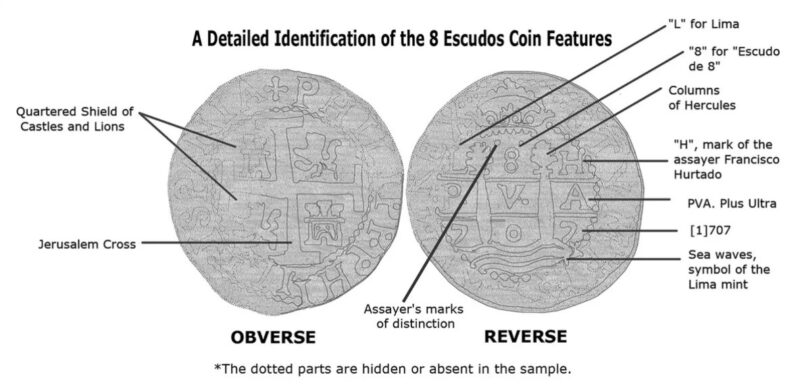

At a depth of around 600m, it is too deep for divers to access. This made it hard for researchers to confirm that it is definitely the San José. The Colombian navy has been using remotely operated vehicles to survey the wreck. The key to proving that it is the San José has been the gold coins scattered on the ocean floor.

Process of elimination

The lead author of a new study, Daniela Vargas Ariza, explained how these coins allow dating of the wreck and its demise through a process of elimination. These particular coins, known as "cobs," show mint marks from Lima, dated 1707. They also have castles, lions, Jerusalem crosses, and other Spanish imperial symbols imprinted on them.

“The finding of cobs...points to a vessel navigating the Tierra Firme route in the early 18th century," said the paper. "The San José galleon is the only ship that matches these characteristics.”

This Holy Grail of shipwrecks is now at the center of a legal battle. Colombia claims it is the sole owner of the wreck under its national heritage laws. They argue that as the ship lies within its territorial waters, it belongs to them. But others want to stake their claim over the ship and its $16 billion of treasure.

Spain contends that the San José is a Spanish ship and so it is Spanish state property. Sea Search Armada says it was the first to identify the general location of the wreck in the 1980s and so should receive some of the compensation. Indigenous communities from countries like Peru and Bolivia are also asserting claims to the treasure since most of it was pillaged from them when they were under Spanish colonial rule.

After hearings in Colombia and the U.S., the decision about who owns the most valuable shipwreck in the world will lie with the Permanent Court of Arbitration at the Hague.

Earlier this year, two amateur metal detectorists unearthed a pair of striking 1,400-year-old artifacts in Wiltshire, England. The gold-and-garnet raven's head and a gold ring with triangular garnet detailing date back to the Anglo-Saxon era.

Paul Gould and Chris Phillips made the discovery on January 8, during a metal detecting rally organized by the 9th Region Metal Detecting Group. Gould found the flattened gold and garnet ring. Shortly after, Phillips uncovered the intricately decorated raven's head. Experts believe the raven's head, which weighs 57 grams, was likely part of a larger object, possibly a drinking horn.

“This is the find of a lifetime…It's unbelievable — I'm a bit emotional," Phillips said in a YouTube video.

In early Europe, ravens were often associated with death. In German and Norse mythology, they were linked with Odin, the Norse god of war. Whether this artifact represented these themes is unclear. The use of garnet and gold was not uncommon during this era. It accurately reflects the level of craftsmanship and techniques from other notable finds, such as those of the Anglo-Saxon burial ship site at Sutton Hoo.

Following the correct procedure, Gould and Phillips properly reported the objects to the local finds liaison officer. Both items are now being cleaned and studied by experts at the British Museum.

Speaking to Live Science, Phillips said, "The finds will go through the treasure process now, which will take a while.” Anything with precious metals that is over 300 years old qualifies as a piece of treasure under the UK Treasure Act. The discovery of two objects so close together suggests the area may yield further treasures from the past.

Two Czech hikers have unearthed nearly 600 gold coins in the Krkonose Foothills, near the Polish border. The pair stumbled across an old metal can sticking out of the ground and opened it to find a cache of coins that date back to 1808.

Beside the can, the hikers found a small iron box filled with cigarette cases, bracelets, combs, a key, and a powder compact. The pair took them to the Museum of East Bohemia. Its chief archaeologist, Miroslav Novak, told the Daily Mail, “I was called to say that a person who had found something was coming to see me. When he opened it, my jaw dropped.”

The 598 coins are all solid gold. Experts estimate that they and the rest of the items are worth an incredible $340,000. Novak added, “The historical value of the treasure, however, is incalculable.”

Mysterious backstory

The coins date from 1808 to 1915, with some extending into the 1920s and 1930s. They also originate from several countries, including France, Austria-Hungary, Belgium, Italy, Russia, and Turkey. All of the coins are stamped with dates, but some also contain a countermarking. This tells us that the coins were reissued in 1921, most likely in the region of modern-day Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Why the hoard was originally buried is a mystery. One theory is that Czech or Jewish individuals concealed the valuables to protect them from the invading Nazis. Another is that fleeing Nazis might have hidden the hoard at the end of the war. The presence of coins from so many countries adds to the intrigue, suggesting a complex backstory.

“It was clearly not about the nominal value of the coins. It’s not about what the coins could buy — that’s not what mattered. It was deliberately hidden because it was precious metal,” explained Vojtech Bradle from the Museum of East Bohemia. After finishing their analysis and conserving the artifacts, the museum will display the collection to the public.

Under Czech law, individuals who discover treasure are entitled to 10% of its value. Given the estimated worth of approximately $340,000, the hikers will receive a substantial reward.

Animals that evolved in warm, tropical climes rarely decide to move to cold, snowy ones. Take any creature from the African grassland and drop it in Austria during an Ice Age, and the poor creature would surely not fare well.

Except Homo sapiens. We did just that, expanding into some of the coldest regions on Earth. New research into a 24,000-year-old site shows how technological innovations helped early humans keep warm during the Last Glacial Maximum.

The early humans of Kammern-Grubgraben

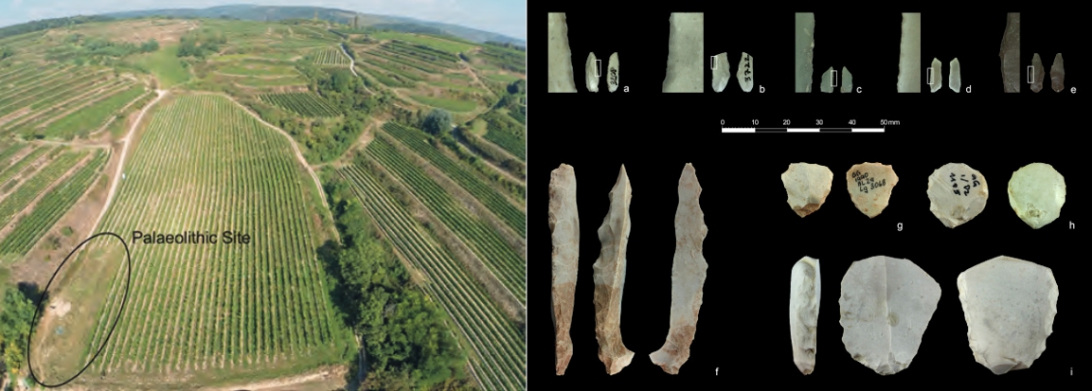

While we tend to associate early humans with caves, Austria's Kammern-Grubgraben site is open air, with a highland on one side and a sloping river valley on another. Between 20 to 24 thousand years ago, humans frequently lived there.

Nearby sites had an even older human history -- 33,000 years. They were hunter-gatherers, who moved with the seasons, returning to the same camps year after year. Sophisticated tool users, they produced a wide range of stone tools, as well as jewelry.

The Kammern-Grubgraben site also contains a wealth of organic remains. Those remains belong almost entirely to one species: Rangifer tarandus, the caribou, or reindeer.

The people of Kammern-Grubgraben hunted caribou almost exclusively during the winter. Researchers knew the hunts had taken place in winter because the skulls still had their antlers, and reindeer shed their antlers after winter. Tooth wear also indicated winter or late autumn deaths.

Why were they only hunting caribou during the winter and autumn? Researchers believe that it was for their hides.

Sewing for survival

As the Thule people in the Arctic discovered much later, caribou hide makes clothing warm enough for almost any conditions. Their thick pelts of hollow, air-trapping hairs conserve heat like nothing else. Once the people of Kammern-Grubgraben acquired these hides, they used sophisticated sewing tools and techniques to create cold-resistant clothing. Sewing traditional fur clothing requires incredible patience and skill, but it can also be incredibly effective. Recreations of Stone-Age clothing handled even in harsh Northern winters.

In the same chronological layer as the caribou bones, archaeologists found eyed bone needles. Eyed needle technology allowed them to sew tight, fitted seams, making clothing much warmer and sturdier than simple draped pelts.

Around 24,000 years ago, the Last Glacial Maximum caused temperatures to plummet. In nearby sites that dated from before this Ice Age, archaeologists found a much broader range of animal remains, and no eyed needles. Here, the most commonly hunted animal was the mammoth, suggesting that hunters prioritized calories over clothing.

When their environment changed, the Stone Age people adopted new lifestyles and techniques to suit their new, chillier environment. This superior winter clothing allowed them to survive an increasingly harsh and unstable climate.

We imagine the ancient world as one made of stone. Marble temples, megalithic structures, and rock-hewn tombs dominate the modern image of the pre-modern period. That image is, of course, an inaccurate one. Stone is all that remains of sites whose flesh was largely made of wood and other fast-decaying plant materials.

This problem of materials is especially relevant to ancient seafaring. Up until the mid-19th century, ships were practically all wood. Worse, the bottom of the oceans tends to be a uniquely bad place to preserve things. Even vessels that sank fairly recently, such as the Titanic and HMS Erebus, are already decaying.

Because of the simple realities of rot, there are very few physical remains of classical-era ships. There is one place, however, where they can be found: the Black Sea.

The Hospitable/Inhospitable Sea

The Black Sea's unique ecological environment allows it to preserve ancient shipwrecks. Its 436,400 square kilometers fill the space between Asia and Europe, but its secret lies beneath that surface.

Ancient Greeks first called the Black Sea Pontus Axeinus -- the Inhospitable Sea. However, as the centuries went on and they established colonies along the coast, they called it Pontus Euxinus, which had the exact opposite meaning from the original name. They couldn't have known this, but these two contrasting names reflected the hidden duality of the Black Sea.

The top layer of the sea is oxygen-rich and therefore able to support complex marine life. Below 100-200m, however, all oxygen is gone. The Black Sea is the world's largest meromictic body of water -- a marine environment with two stratified layers that never mix.

The two layers exist because water only enters the sea near the surface, from rivers like the Danube and Kuban, and out through the shallow Bosphorus Strait. No water mixing happens below 150m.

Honestly, I was simplifying too much when I said there were only two layers. There are actually secret intermediate layers that keep the upper and bottom from mixing, but for our purposes (shipwrecks) there are two: oxygen-rich upper, anoxic bottom.

That bottom layer is actually most of the sea. Only 13% of the Black Sea is oxygenated. The anoxic layer is a pretty bad place to be alive, but a good place to be a shipwreck.

A hot spot for shipwrecks

The same currents and tides that wreck ships on the surface can also damage them once they've already sunk. Wrecks near rocky coasts are particularly vulnerable and are soon smashed to bits and dispersed.

In addition to those ocean forces, the shipwreck has many natural predators. Organisms like shipworms, gribble (a type of marine isopod), and other wood borers quickly attack exposed beams. Materials buried under sediment will be eaten by bacteria, which feed off sugars like the cellulose and hemicellulose in wood.

So the quiet, deep waters of the Black Sea anoxic zone present an ideal, shipworm-free environment. In 1976, Willard Bascom, an engineer and marine archaeologist, wrote about the possibility of Black Sea anoxic waters preserving a wealth of ancient wrecks.

The Black Sea is also well-situated for wrecking ships in the first place. People have lived along its coasts for tens of thousands of years. Over the centuries, its location between Europe and Asia, connected to the Mediterranean and several major rivers, made the Black Sea a locus of ancient travel and trade.

Its waters were a theater for maritime history, hosting Hittites, Thracians, ancient Greeks, Persians, Scythians, Romans, Byzantines, Huns, ancient Slavic groups, Goths, Vikings, medieval Italian traders, Ottomans, and more.

Technological limitations, however, long prevented investigation of its depths.

Testing the waters

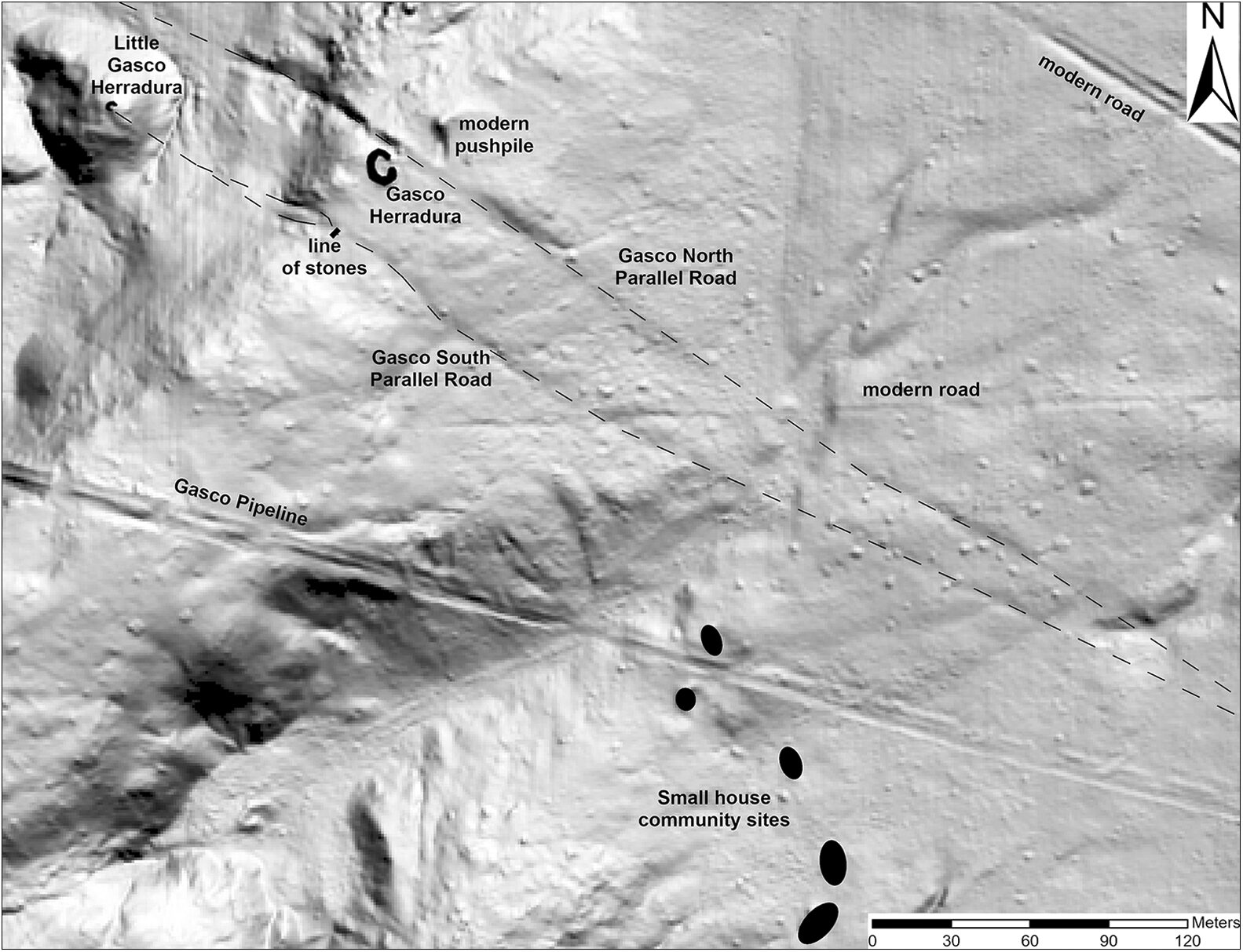

In 2000, Robert Ballard led an expedition to the northeastern Turkic coast of the Black Sea. Ballard pioneered new deep-sea exploration techniques that led him to discover the wreck of the Titanic. Searching off the coast between the Bosphorus and Sinop, the team was also looking for Bronze Age coastal settlements.

The Black Sea Deluge hypothesis proposes that until about the 7th millennium BCE, the Black Sea was a smaller freshwater lake, and people lived on its banks. When the Bosphorus opened, the Mediterranean flowed in, transforming the lake into an inland sea. Finding evidence for this theory was a major goal of Ballard's expedition.

Using a combination of sonar and remotely operated vehicle (ROV) technology, the 2000 expedition surveyed the sea floor. Argus, a small imaging vehicle equipped with lights to illuminate the ocean floor, was dropped over the side and dragged behind a boat. The other vehicle was remotely operated and attached to Argus. Called the Little Hercules, researchers deployed it to recover objects or samples.

Under 100m of water, researchers traced what they believed to be an ancient shoreline, finding freshwater snail shells and a possible Neolithic settlement, which they named Site 82. Ballard and his team theorized that the regular limestone blocks were the remains of a manmade settlement.

Twenty-five years later, we still aren't completely sure how the water level in the Black Sea has changed over time. But it probably isn't as simple or dramatic as the Flood Theory posits. For half a million years, the Black Sea has been repeatedly isolated and connected as water levels fluctuated. But these are gradual processes -- there just isn't a lot of physical evidence for a catastrophic, sudden deluge.

But what about the shipwrecks?

Whether Site 82 is a neolithic settlement or just some squarish limestone, it was only one of several key finds. Up to about 85m of depth, years of bottom-net fishing have effectively destroyed the archaeological record. So they began at that depth, scanning a 50km stretch of coast between 85 and 150m.

In a fairly short time, they began getting hits. First, Shipwreck A: two clusters of ceramic vessels and a few half-buried planks, dated to the Late Roman era. Shipwreck B: more ceramic jars and submerged hull planks. The outline of this vessel is larger, and it appears to have a bilge pipe to pump water out of the ship. Based on this, researchers dated it to the Byzantine era. Shipwreck C was similar to Shipwreck A.

Shipwreck D

The promising findings offered new information on the location of an ancient trade route. But very little remained of the ships themselves; the water wasn't deep enough to preserve them. Off this coastal shelf, the sea bottom slopes abruptly downward to depths of 1,000m and more.

They turned to the trickier, deeper waters, with little initial success. With the expedition about to end, Ballard and his team made one final sweep -- and found something.

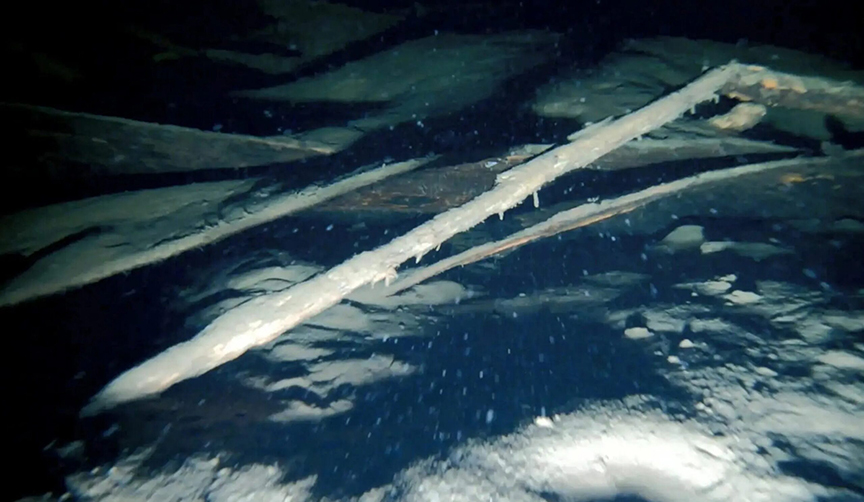

Shipwreck D sits upright in 320m of water. It's remarkably well preserved, with a deck structure, rudder, and mast rising 11m from the hull. There is even cordage wrapped around the top of the mast. Little Hercules collected a sample of the wood from the rudder area. The samples dated to 410-520 AD.

For such an old ship, it was shockingly well preserved, giving archaeologists insight into the construction of Byzantine ships. However, Shipwreck D, now called Sinop D, is most important as a sign of what else could be out there.

What else was out there?

Ballard and his team returned several times during the 2000s on further expeditions. They continued deploying Argus and Little Hercules to investigate sonar hits.

The technology continually improved, but was still a work in progress. Out of 500 hits, only 44 could be identified, and some of them turned out to be trash. The non-trash spanned a thousand years of history: An early medieval jar wreck, a 19th-century warship, three airplanes and even a WW2 Soviet destroyer, the Dzerzhynsky, named after the founder of the KGB.

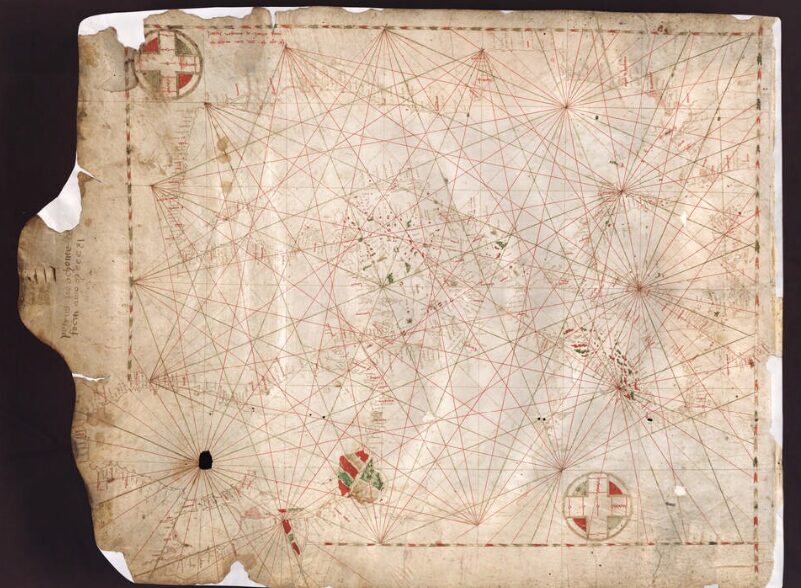

Almost 10 years later, The Black Sea Maritime Archaeology Project used its ROVs in the Black Sea. A team from the University of Southampton set out on Stril Explorer, a state-of-the-art offshore survey vessel. They were there for the same ancient coastline debate Ballard investigated in 2000. It was almost by accident that acoustic and sonar data, combined with over 250,000 photographs, allowed them to find, map, and model 65 shipwreck sites.

Like the Ottoman ship above, most of them were trade vessels that sank in bad weather. They were far out to sea, along known routes. All were remarkably well preserved. One 13th or 14th-century Venetian vessel was the most complete of its type ever discovered. But the most impressive find was still yet to come.

The world's oldest intact shipwreck

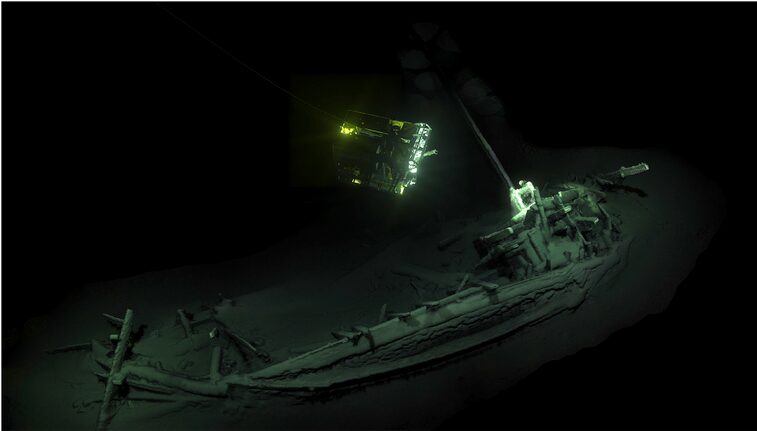

More than two kilometers under the surface of the Black Sea, off the coast of Bulgaria, lies a ship that is more than 2,400 years old. It was an Ancient Greek trading vessel, loaded up with goods meant for Greek colonies on the coast of the Black Sea.

The anoxic water has done its job; the 23m-long ship has an intact hull, with its precious cargo still hidden inside. The mast stands ready for winds that blew before the birth of Alexander the Great. There are intact benches for rowers who died before the invention of the number zero.

Because the cargo, which would usually be used to date the vessel, was inaccessible, the ROV took a small sample to carbon date. The result confirmed what the ship's design had suggested: It came from the 4th century BCE.

University of Southampton Archaeology Professor Jon Adams, who led the Black Sea MAP project, was stunned. An intact shipwreck of this age was unheard of. In fact, they could only recognize the ship's design from depictions on ancient pottery.

"This will change our understanding of shipbuilding and seafaring in the ancient world," Adams said in a press release.

This find is the world's oldest known intact shipwreck. Ships have sailed the Black Sea for over 2,400 years, though. Only a small fraction of its depths have been explored, and even older shipwrecks are still waiting to be found.

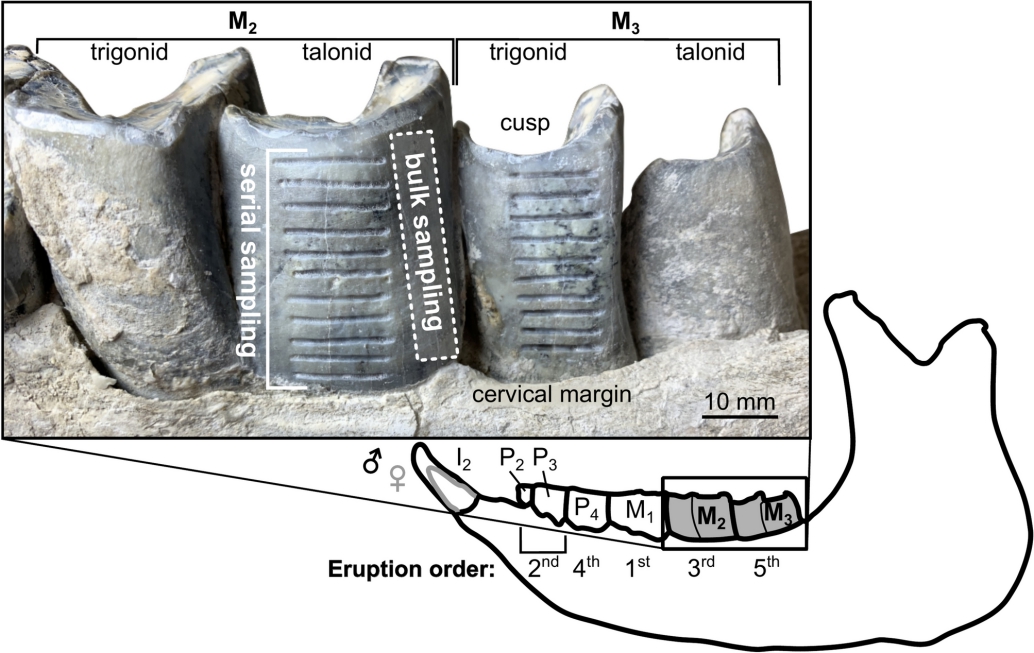

For over fifty years, a prehistoric rhinoceros mass grave has baffled paleontologists. Over one hundred rhino skeletons were found in the same spot, having all died together 12 million years ago. Now, a new study has revealed that this mass of animals, which died together, also lived together in one huge herd. How do we know? Their teeth.

Rhinos buried in ash

Located about 160 km from Sioux City, Iowa, the Ashfall Fossil Beds were created by the Yellowstone volcanic eruption 11.9 million years ago. When the volcano blew, a dense blanket of ash covered the entire region. Smaller animals died almost instantly, suffocating on the abrasive ash.

For larger, hardier creatures like the Teleoceras major, the barrel-bellied rhino, it was slower. Volcanic ash, on a microscopic level, is actually quite sharp, like tiny shards of glass. As it filled their lungs, animals slowly sickened and died. They came to the watering hole, seeking some relief in the cool water. There they died, and the wind swept more ash on top of them. What had killed them also preserved them perfectly.

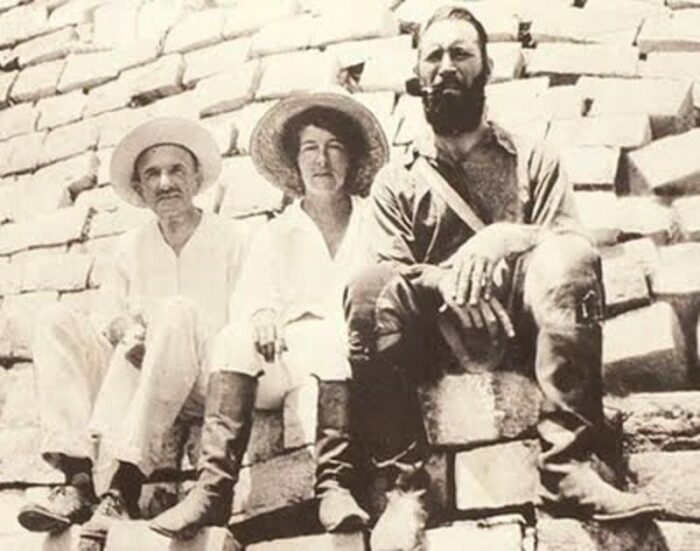

In 1971, Michael and Jane Voorhies were walking down gullies in Northwestern Nebraska. Michael was a University of Nebraska State Museum paleontologist who hoped that erosion by nearby Verdigre Creek had revealed fossils.

It had. Emerging from the side of a gully was a flash of white bone, suspended in ash. Michael had found the skull of a baby rhinoceros. Excitingly, the skull was still connected to the neck, and the neck to the body.

Six years later, Dr. Voorhies came back with a crew from the University. The site is now part of a national park and is still an active dig site. The animals are suspended in layers showing their order of death: Small birds at the bottom, which succumbed first, then horses and camels, and rhinos last. There are over 20 species in total, and hundreds of skeletons, most of them rhinos.

Enamel revelations

However, paleontologists weren't sure at first why the rhinos had all come together in such huge numbers. Were these separate individuals and small herds, all fleeing to the same hole? Or could they really be part of a single massive herd? Researchers at the University of Cincinnati set out to answer the question.

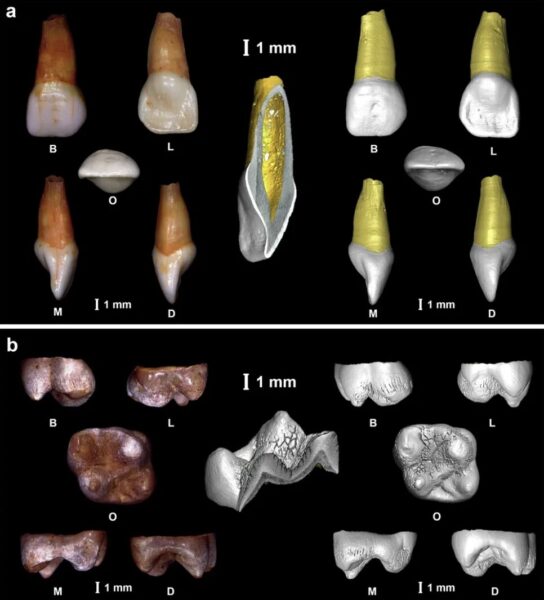

They took samples from the tooth enamel of more than a dozen individuals. Then they analyzed the isotope ratios present in the enamel. Atoms of the same element can have different numbers of neutrons, resulting in different "species" of a given element. Isotope analysis measures the relative amounts of these different species of element. Because different isotopes occur in different environments, and therefore different foods, isotope analysis tells scientists what (and therefore where) an animal was eating.

Using this analysis method, they were able to examine where and why the individuals were moving. Had they traveled a long distance to avoid destruction? Did they migrate seasonally, or leave for new territory upon reaching adulthood?

As it turns out, the answers to those questions are no, no, and no. All the individuals they sampled had been eating the same local food for their whole lives. Comparing their isotopic signatures to another local animal, a sabre-toothed deer, revealed a more aquatic diet. If T. Major was semi-aquatic, like modern rhinos, this would have restricted its movement, explaining the lack of migration.

The hundred-strong rhino group at Ashfall hadn't come together by chance, all fleeing the same disaster. They were one large herd, who had lived together and died together.

A stroll through prehistoric Nebraska

Before the eruption, Mesozoic Nebraska was a vast savannah, crisscrossed with streams and watering holes. Grazing animals fed on the open grasslands. The long-necked Aepycamelus, a giant extinct camel, grazed on the treetops, while small three-toed horses like Pseudhipparion gratum and Neohipparion affine munched on the grass beneath them.

The smaller grazing animals and the young of their larger cousins had a number of canine enemies to watch out for. The deadliest of them was Epicyon, the massive "bone-crushing dog" that weighed up to 170 kilograms.

Moving placidly along riparian corridors were great masses of barrel-shaped T. Major. Growing up to four meters long, they were low to the ground, built more like the modern hippopotamus. In massive herds of dozens of these fleshy, tusked tanks, they enjoyed their muddy wallows, unconcerned by the bone-crushing dogs.

The volcanic eruption was not the end of T. Major. The rhino species persisted for another seven million years, until climate change froze its wet, temperate grasslands.

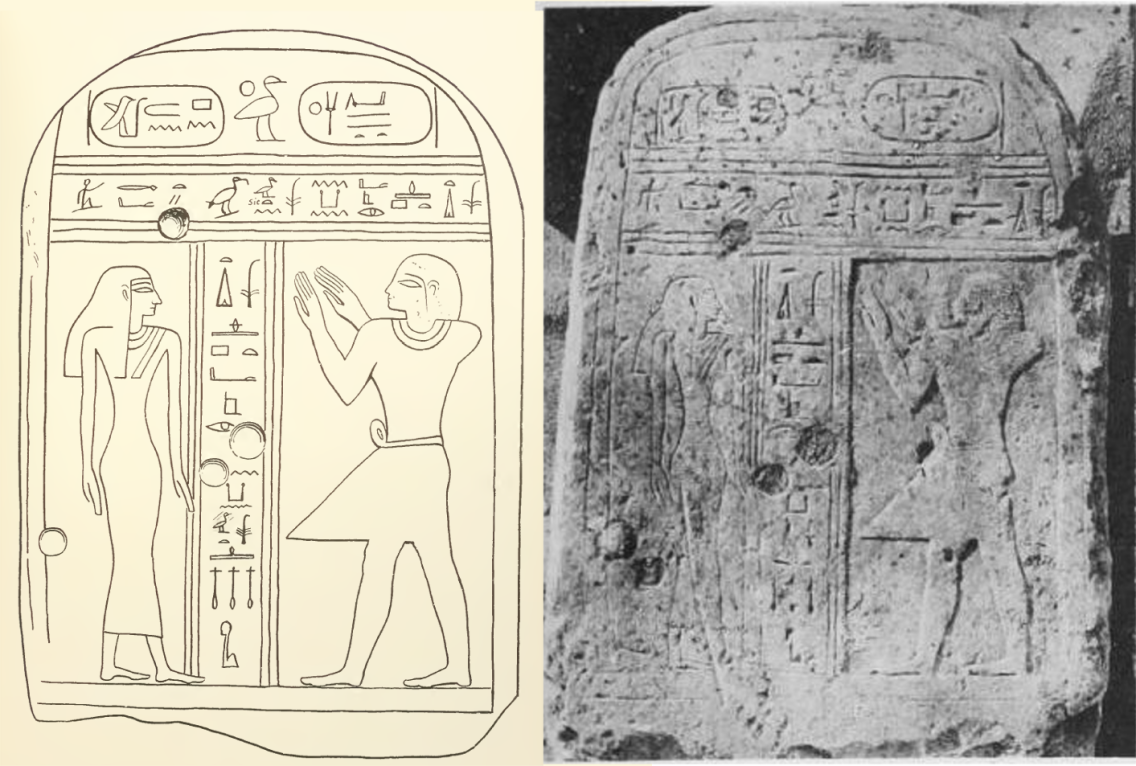

Archaeologists from the University of Pennsylvania were investigating Abydos, one of Egypt's most ancient cities, when they found a 3,600-year-old royal tomb.

From its location near the Mount Anubis necropolis and the surviving inscriptions, Egyptologists know the tomb belonged to a little-known royal family, the Abydos pharaohs. The discovery sheds light on a lost dynasty whose very existence scholars have debated.

Who were the Abydos pharaohs?

It's difficult to imagine how long the Ancient Egyptian civilization persisted. In England, there have been seven different ruling dynasties since the Middle Ages. Egypt had roughly 33 dynasties.

This makes it a little easier to understand how an entire ruling family could slip through the cracks of history. The existence of the Abydos dynasty was first proposed in the 1990s and only confirmed by the discovery of a tomb in 2014. This second tomb provides more evidence.

Egyptologists believe the Abydos pharaohs ruled from 1700 to 1550 BCE. This Second Intermediate Period marked the chaotic transition between the Middle and New Kingdoms, a time of famine, warring dynasties, and rapid regime change.

The last Middle Kingdom dynasty was when the Hyksos people swept into Egypt. They conquered the Nile Delta area known as Lower Egypt, becoming the 15th Dynasty.

Upper Egypt, meanwhile, was split in two. The 16th dynasty ruled Thebes and its surrounding area. The area around Abydos was ruled by, you guessed it, the Abydos Dynasty. The area was fairly small, and the Abydos reign short. They left few monuments behind.

Turin King List

The Turin King List, compiled by the famous 19th Dynasty King Ramesses II, only chronicles four Abydos rulers. The list detailed every pharaoh before Ramesses II.

However, the list was discovered in fragments, with some sections lost, so a degree of guesswork is involved. Pharaoh Senebkay, whose tomb was discovered in 2014, is not one of the four Abydos rulers on the Turin King List.

The new grave belonged to someone who was likely an ancestor of Senebkay, as they were buried in a similar style. Beyond that, Egyptologists can only guess.

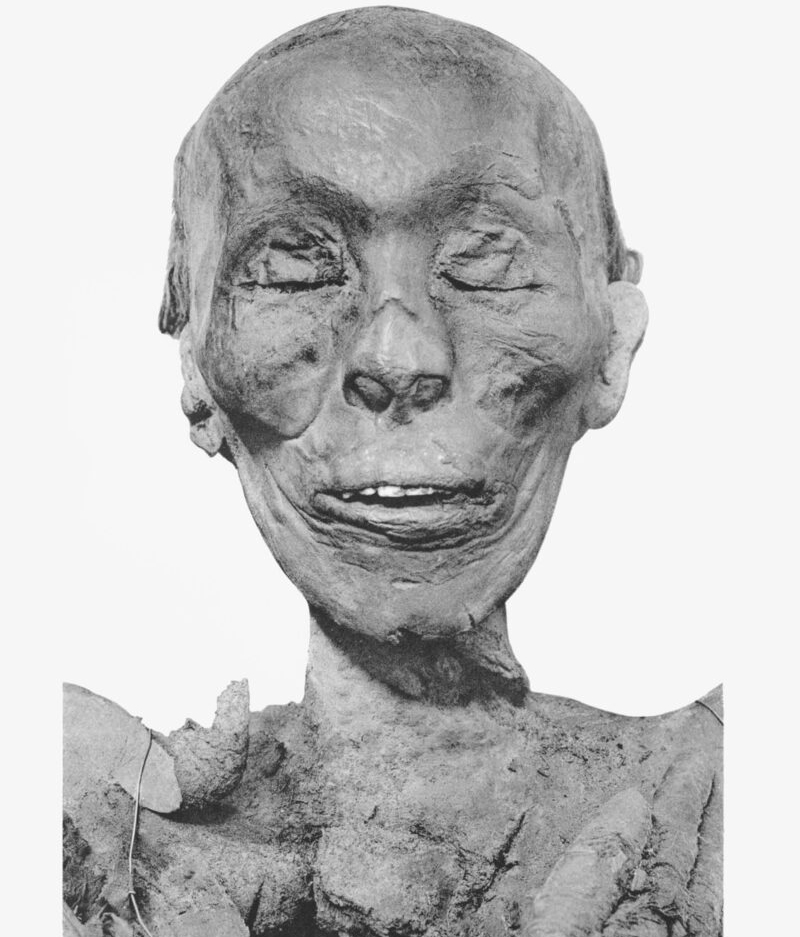

Looters stole the grave goods and the mummy and damaged the inscriptions. On either side of the tomb entrance, yellow bands once showed the pharaoh's name and images of the goddesses Isis and Nephthys. You can still make out the sister deities, but the name has vanished.

The Pennsylvania team, led by Josef Wegner, believes the tomb could belong to either Senaiib or Paentjeni. Both have monuments in the area, and researchers have not found either of their tombs.

More to find

The Abydos tomb is the second royal grave Egyptologists have unearthed this year. The first belonged to Thutmose II, husband of the famous female pharaoh Hatshepsut.

Wegner and his team will continue excavations near Mount Anubis. More Abydos dynasty and Middle Period kings may be in the necropolis, Wegner believes.

For the Ancient Egyptians, Abydos was the burial place of the god Osiris, ruler of the afterlife. This made it a sacred city and the burial site for many of the earliest pharaohs. The kings buried here are much older than Thutmose II or the famous Tutankhamun, and their lives are much more mysterious. The Mount Anubis excavations may unearth their long-buried history.

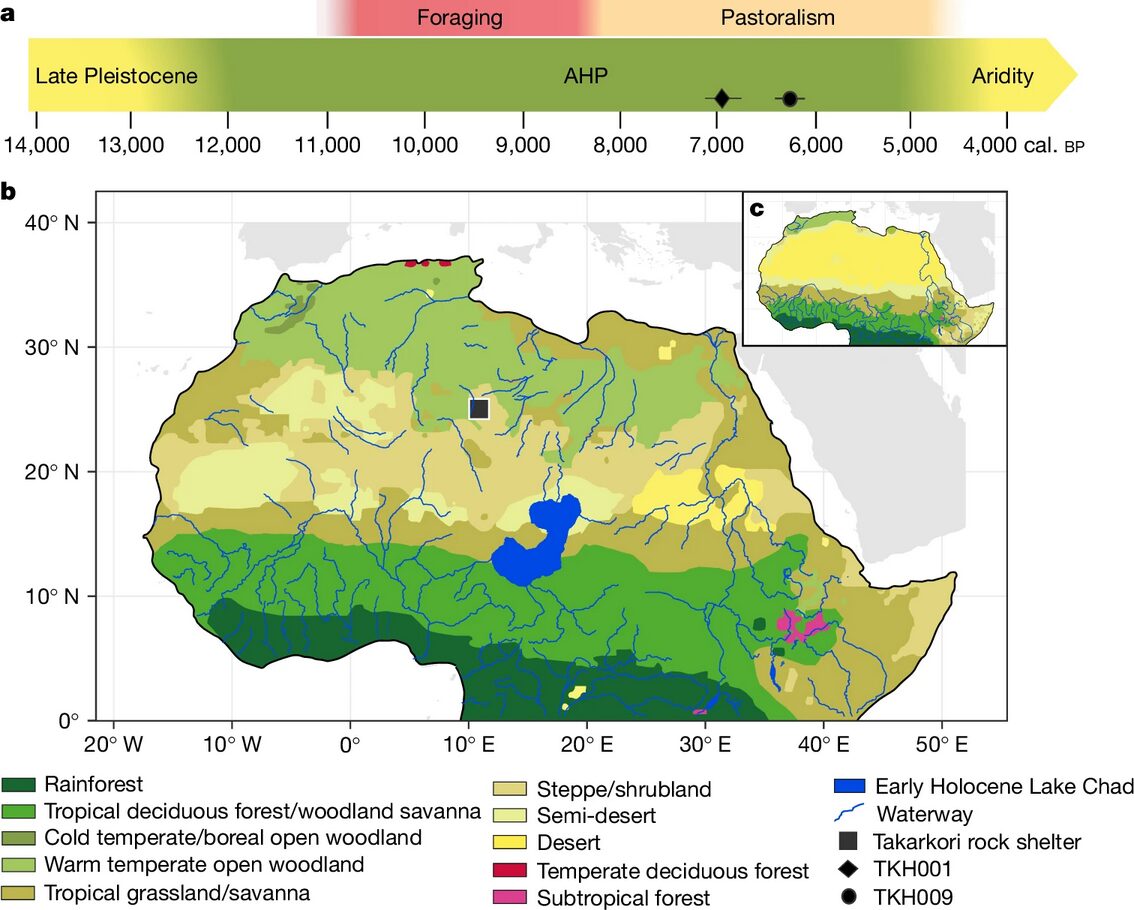

Lush greenery is as unexpected in the Sahara as it is in Antarctica. Yet both were once home to more temperate ecosystems. Unlike the jungles of Antarctica, which froze away many millions of years ago, the Green Sahara was recent enough to host early humans.

Every 21,000 years, the Sahara experiences a wet, rainy period, turning it into a woodland. The last North African Humid Period occurred between 14,500 and 5,000 years ago. During that time, an enigmatic group of pastoral people called the region home.

But who exactly were they? Where did they come from? What happened to them when their home became a desert again? All this has long been a matter of debate.

A new study in Nature reveals the results of DNA testing, suggesting a clearer origin for the Green Sahara people.

Deciphering an ancient genome

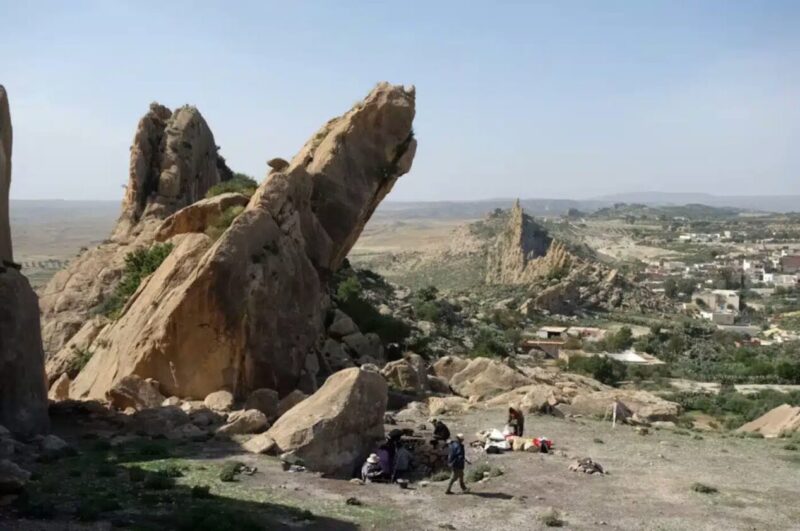

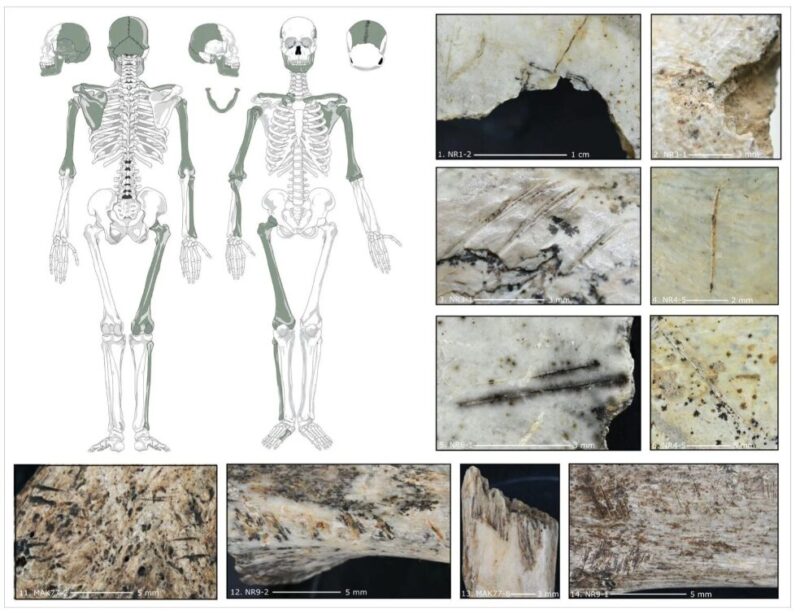

The Takarkori rock shelter is tucked against the Tadrart Acacus Mountains of southwest Libya. Humans lived here from 10,200 to 4,200 years ago. Archaeologists have unearthed a number of artifacts, the most important finds are the 15 sets of human remains in the back of the cave.

A team from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Germany decided the most likely remains for testing were a pair of adult female mummies carbon-dated from 6,800 to 6,300 years ago. Carefully, researchers extracted genetic material from their naturally mummified remains.

Conditions in the Sahara degrade DNA, making research into population change extremely difficult. The DNA was too damaged to construct a complete genome, but researchers were able to compare specific sections of code to almost 800 individuals from modern Africa, the Near East, and Southern Europe.

The unique people of the Green Sahara

Genetic analysis revealed that the Takarkori people were part of a unique, somewhat isolated group. Their overall ancestry was North African, and significant migration in or out of their population had not occurred.

This runs counter to previous theories, which suggested northward migration from sub-Saharan Africa. Around the height of the last humid period, the Green Sahara people moved from hunter-gathering to a more sedentary herder's life. Previously, researchers believed that sub-Saharan people moving through the area had introduced domestication.

The Takarkori people. also had far less Neanderthal DNA than other North African populations. They were fairly isolated genetically, but with a moderate population of around 1,000 people, they weren't in a population bottleneck.

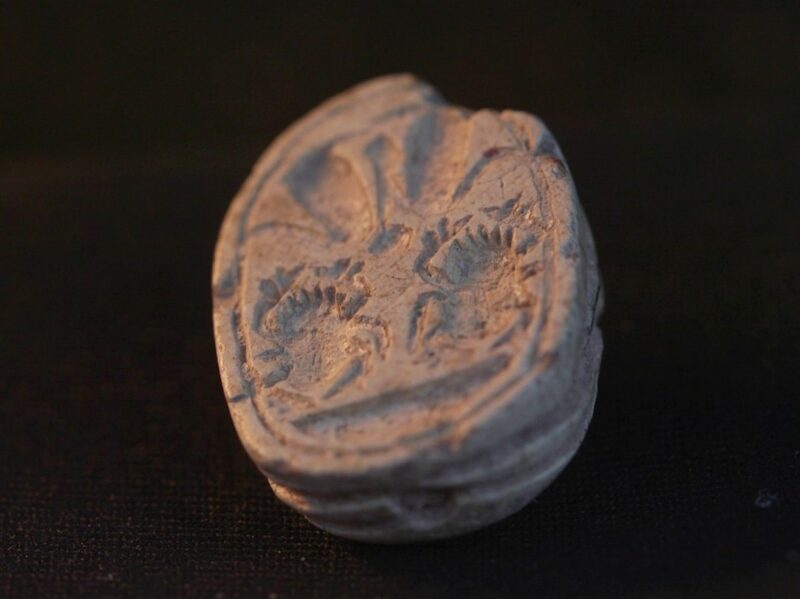

When kids are outside they pick up anything that catches their eye -- an oddly shaped rock, leaves, sticks, bugs. There are endless possibilities. But when three-year-old Ziv Nitzan was out walking with her family near Tel Azekah in central Israel, she picked up something far more unusual: a 3,800-year-old Egyptian artifact.

The small object she found is an ancient scarab amulet dating back to the Middle Bronze Age.

“Out of the 7,000 stones around her, she picked up one stone,” Omer Nitzan, Ziv's older sister, said in a statement. "Then she brushed off the sand and saw that something was different about it. I called my parents to come see the beautiful stone and we realized we’d discovered an archaeological find!"

Ancient scarab

Tel Azekah is a known archaeological site, and excavations have taken place there for around 15 years. Shaped like a beetle on one side and with engravings on the other, Nitzans' parents knew they might be looking at something old and valuable. They contacted the Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA).

The IAA confirmed the authenticity and significance of the Canaanite scarab. The Canaanites were an ancient Semitic people who lived across parts of modern-day Israel, Palestine, Lebanon, Syria, and Jordan.

“Scarabs were used in this period as seals and as amulets," explained Daphna Ben-Tor from the IAA. "They were found in graves, in public buildings, and in private homes. Sometimes they bear symbols and messages that reflect religious beliefs or status.”

Tel Azekah was an important city in the Judean Lowlands during the Middle and Late Bronze Ages. Archaeologists have discovered many Egyptian and Canaanite objects in the area.

“The scarab found by Ziv joins a long list of Egyptian and Canaanite finds discovered here, which attest to the close ties and cultural influences between Canaan and Egypt during that period,” commented Oded Lipschits, director of the Tel Aviv University excavations at the site.

How did it wind up on a hiking trail?

Lipschits also explained how the ancient artifact ended up on a hiking trail. In 1898, when excavations first took place at that site, British archaeologists found an acropolis, a citadel, and an array of artifacts. After their dig, the man who owned the land asked them to fill the area they had excavated so he could farm there.

“So the modern layers are now inside, and the old layers that used to be very deep in the ground are now on the surface, Lipschits told The New York Times. "This is why people can find all kinds of ancient items like these scarabs on the surface.”

Experts will now study the amulet further. Nitzan and her family received a certificate of appreciation from the Israel Antiquities Authority for their “good citizenship.”

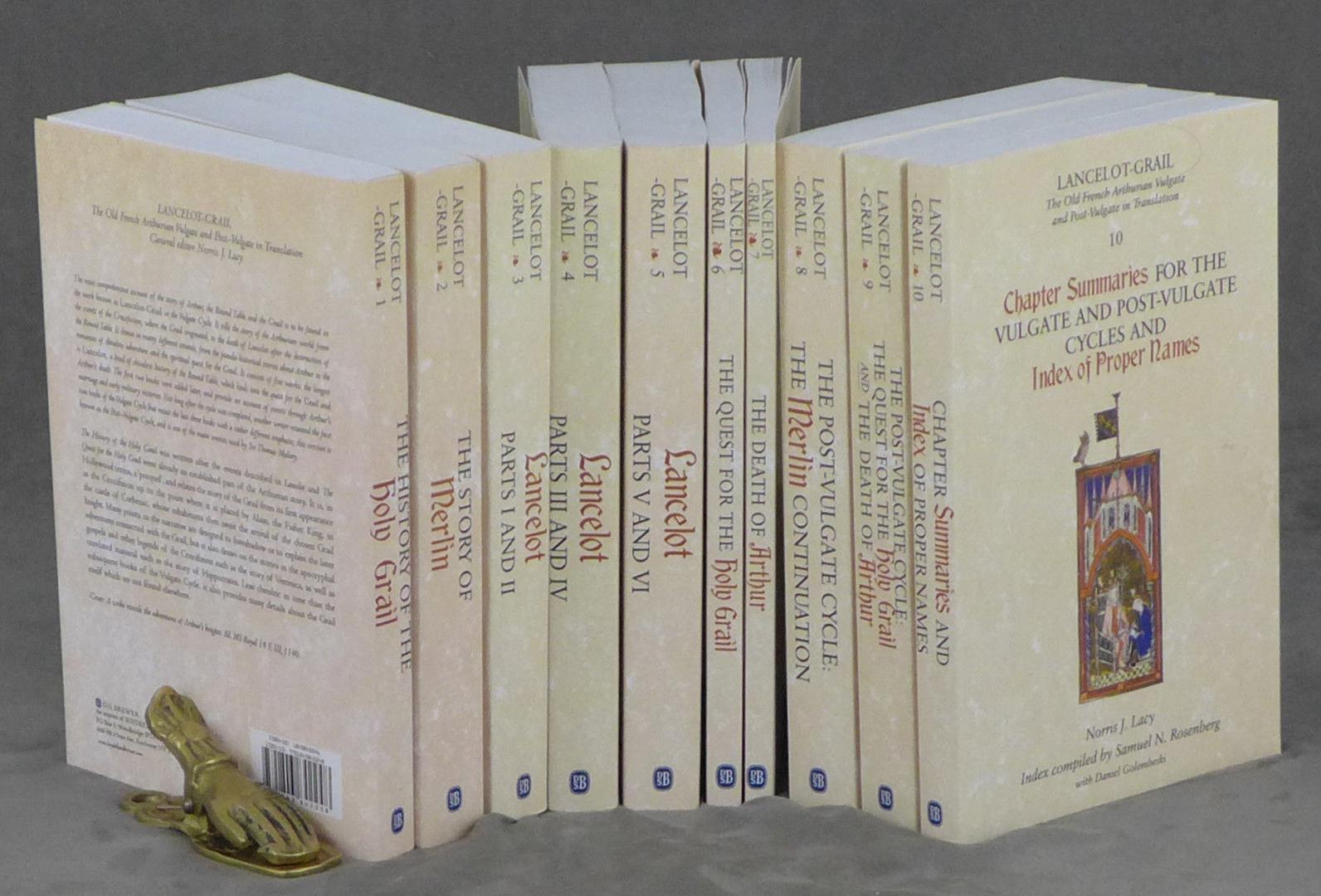

In the dying years of the Roman Empire, a vassal king in the distant territory of Wales rallied his forces to shake off Roman rule. When the Saxons, too, turned their eye on his kingdom, that Welsh king joined with his northern confreres to beat them back. Eventually, he founded a model kingdom 800 years ahead of its time, complete with knights, metal armor, and even an early form of parliament.

His name was King Arthur, and unfortunately he did not exist, at least in a recognizable way. But the late medieval writers who crafted his legend would have had cause to rejoice this week. Digital archivists at the Cambridge University Library have just recovered a new fragment of their work, hidden in plain sight for centuries. It had been used as the binding for an Elizabeth property register.

How a 13th-century story became the cover of a 16th-century book

Stories of King Arthur were all the rage in the 1200s. After the self-described historian Geoffrey of Monmouth popularized Arthur's legend in the 11th century, the setting of the Round Table spread across the Channel. What had once lived in the realm of pseudo-historical tracts and Welsh oral tradition reached the courts of France.

The defining stories of early French Arthuriana were poems. Marie de France, one of the most famous female French authors in history, wrote short, often satirical verse set in Arthur's court. At the same time, the daughter of Eleonore of Aquitaine, Marie de Champagne, commissioned the first stories of Sir Lancelot and Queen Guinevere's forbidden love and of the Grail Quest.

These stories captured the imagination of the French and English nobility, culturally bound from the Norman conquest of England in 1066. In about 1200, an anonymous coalition of authors adapted them into what may be the first European fantasy blockbuster: the five-book series known as the Vulgate Cycle.

The Vulgate Cycle

Novels were a new concept in Europe. But the magical quests, epic sagas of family strife, and heart-rending character arcs of the Vulgate Cycle were so successful that they endure even today. If you've heard of the Lady of the Lake, of Lancelot and Guinevere's affair triggering the downfall of Camelot, of the Holy Grail being the cup that caught Christ's blood on the cross, then that's the Vulgate Cycle at work.

By the 16th century, though, stories of the Round Table were passé, especially in England. In the same way that a 21st-century scrapbooker might dismember an old novel, Elizabeth bookbinders yanked out a handful of pages from a copy of a Vulgate book. The copy they used dated to about 1300. They needed to bind a register of property deeds, and parchment was precious. So they folded up the Vulgate pages and sewed them into a new cover. There, the pages sat for half a millennium.

Recovering the story

In 2019, archivists at Cambridge University were sorting through the records of an estate in Suffolk when they realized that the cover of the property register contained fragments of a much older text. But it would be impossible to unfold the fragments without damaging the cover it comprised, an important historical artifact itself. More advanced methods would be needed to read the cover text, and in 2023, Cambridge began a new program to do so.

Just this week, the Cambridge Digital Library released the first results from this project. Archivists used multispectral imaging (MSI) to scan the whole text without unfolding the cover. MSI breaks images down into color categories, allowing conservationists to deblur old writing or even recover the traces of erased text.

CT scans probed through the folded layers of parchment. Finally, new techniques in digital image manipulation allowed the team to "unfold" the text and read it.

The wizard Merlin greeted them.

Merlin's magical shenanigans

Nowadays, images of Merlin are dominated by two pop culture phenomena. Either he's a spry old wizard in a blue hat who ages backward (as portrayed in TH White's The Once and Future King and its Disney adaptation, The Sword in the Stone), or he's Arthur's 20-something best friend, as in the BBC TV show Merlin.

The medieval Merlin was a lot stranger. He was born speaking like an adult, the child of a human woman and a demon. He could disguise himself however he wished and was prone to prophesying the downfall of those around him. (Personally, if my wizard advisor handed me a sword inscribed with the words, "With this sword, Sir Lancelot shall kill the man he loves most, and that man shall be Sir Gawain," I wouldn't let anyone named Lancelot or Gawain anywhere near my peaceful Round Table.)

On one occasion, Merlin arrived at Camelot disguised as a blind harpist: "While they were rejoicing in the feast, and Kay the seneschal brought the first dish to King Arthur and Queen Guinevere, there arrived the most handsome man ever seen in Christian lands. He was wearing a silk tunic girded by a silk harness woven with gold and precious stones, which glittered with such brightness that it illuminated the whole room."

This is the excerpt that made up one of the two pages sewn into the cover. So far, the Cambridge Digital Library has only released the above passage, which agrees with other copies of the Vulgate Cycle. They are currently working to produce an annotated version of the whole text. Medieval scribes often edited or even rewrote the stories they copied, so it's possible this text could differ substantially from other manuscripts.

A medieval action hero

Although nowadays Arthur and Merlin are probably the most famous characters from the Arthurian canon, medieval readers had a favorite knight, and it wasn't Lancelot. It was Arthur's hot-headed, charismatic nephew Gawain.

Arthur has a relatively idyllic childhood in the Vulgate Cycle. A kindly knight raises him alongside his own son. But the children of his elder sister Morgause are less lucky. From a very young age, they fight alongside their father in wars against the Saxons. In addition to the Merlin episode, the property register cover text also includes a scene from this plot arc, in which Morgause's eldest son Gawain rides his beloved horse Gringolet into battle.

This is one of the final snapshots of Gawain as a teenager in the Vulgate Cycle. Soon after, one of Arthur's knights kills his father in battle. The young Gawain vows revenge, and although he later joins the Round Table, his vendetta against his father's killer spirals into a vicious blood feud that contributes to the fall of Camelot.

Of course, that's the version in other manuscripts. In the property register folio, none of that ever happens. Merlin dazzles Arthur's court, and Gawain rides victorious into battle. The rest is left to the reader.

When exactly did human language emerge? A new study suggests that humans have been chatting away for at least 135,000 years.

Researchers from MIT took a new approach to unravel that old mystery. Rather than look at fossils and artifacts, they studied the movement of ancient populations via 15 genetic studies conducted over the past 18 years. Three featured Y chromosome analysis (tracing paternal lineage), three examined mitochondrial DNA (tracing maternal lineage), and nine were whole-genome studies. All indicated that early Homo sapiens began diverging around 135,000 years ago.

The researchers believe it is likely that all languages stem from a single original one. This would mean that ancient humans had the capacity for language before we spread across the planet.

"All languages are related," explained lead author Shigeru Miyagawa. "The first major split among humans occurred around 135,000 years ago, so we can infer that language must have existed by then — or even earlier."

All languages linked

Previous 2017 research suggested a similar idea but was based on fewer studies. “Quantity-wise, we now have more studies, and quality-wise, we have a narrower time window,” Miyagawa said. A linguistic expert, he believes that all languages are linked. In the past, he has studied the similarities between English, Japanese, and some Bantu languages.

Some believe that language can be traced back millions of years based on the vocal abilities of other primates. But while primates can make sounds and communicate with each other, it is nothing like human language. For Miyagawa, the question is not when primates could make certain sounds but when ancient humans developed the cognitive ability to develop a language.

“Human language is different because there are two things –- words and syntax -- working together to create this very complex system," he explained. "No other animal has a parallel structure in their communication system. And that gives us the ability to generate very sophisticated thoughts and to communicate them to others.”

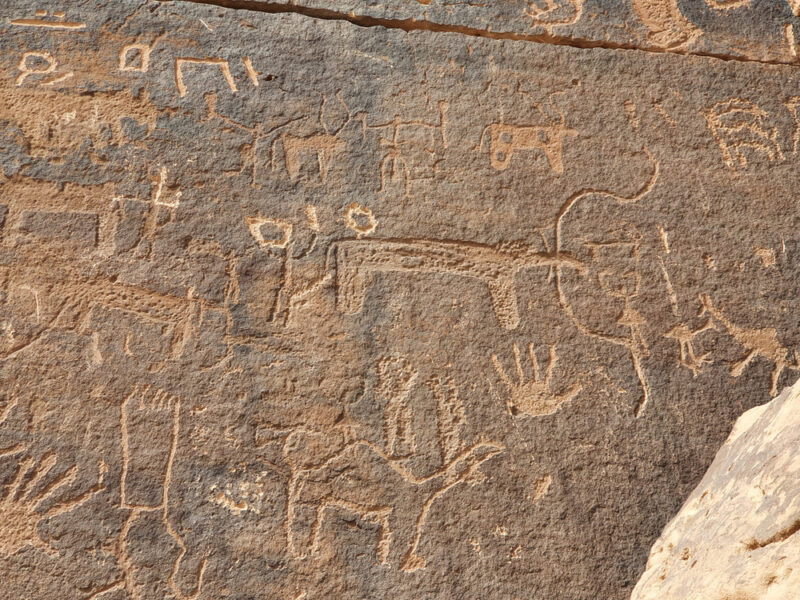

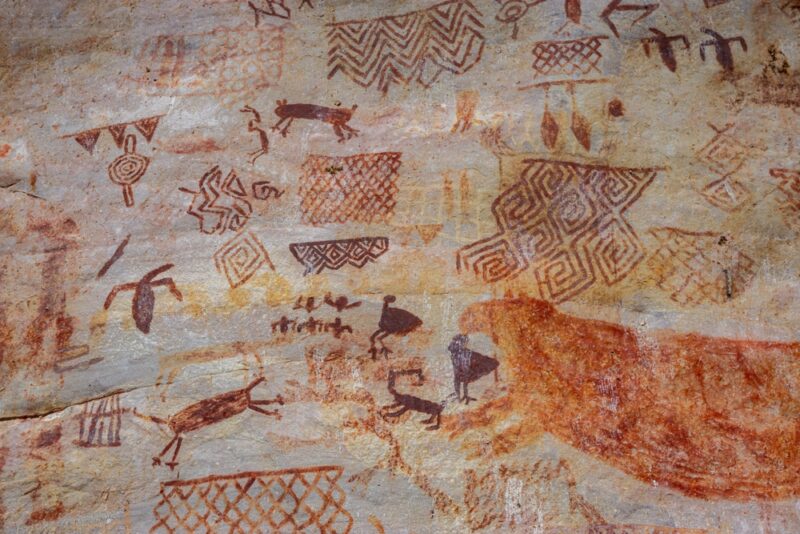

A second question is when we started using language socially and in our daily lives. Archaeological evidence suggests that widespread symbolic behavior emerged around 100,000 years ago. Artifacts such as engravings on stone walls show abstract thinking and the ability to convey a message or piece of information.

“Language was the trigger for modern human behavior,” Miyagawa says. “Somehow, it stimulated human thinking...If we are right, people were learning from each other [thanks to language] and encouraging innovations of the types we saw 100,000 years ago.”

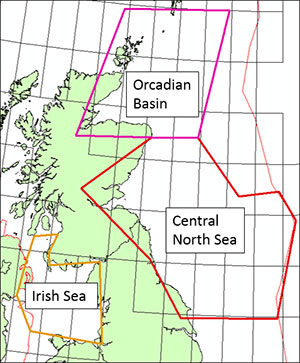

DNA analysis has revealed that Stone Age people from North Africa descended partly from European hunter-gatherers. This shows that early people not only came out of Africa but, much later, some returned to it by boat across the Mediterranean.

Researchers analyzed the genomes of nine individuals from archaeological sites in present-day Tunisia and Algeria, all dating from 6,000 to over 10,000 years old. The remains showed genetic markers that linked them to Europeans.

One individual from Djebba, Tunisia, had approximately 6% of his DNA traced back to European forebears. The intermingling took place around 8,500 years ago. A woman from the same site showed similar European genetics.

It is difficult to determine exactly where European ancestry comes from. It could have come from Sicily or a small island called Pantelleria between Sicily and Africa.

Island hopping

It seems unlikely that prehistoric humans crossed the Mediterranean in a single journey. Instead, the new study suggests that they island-hopped across the Sicilian Strait. Proving this theory will, however, be difficult. Many of the islands that could have acted as natural stopping points are now completely submerged, alongside any archaeological evidence they might have held.

No boats from this period have ever been found in North Africa, but dugout canoes of that age have turned up in Bracciano Lake, Italy. This proves that ancient Mediterranean populations were capable of creating seafaring vessels that could have made the journey.

Archaeologists have unearthed five ceramic puppets from a pyramid in San Isidro, El Salvador. The figurines date back 2,400 years, and significantly, all have dramatic facial expressions.

The figures depict four women and one man, and their expressions change depending on the viewer's perspective. At eye level, they appear angry; from above, they seem to be grinning; and from below, they look scared. Researchers believe this enhanced the puppets' roles in rituals and storytelling.

Each of the small statues has small holes drilled into it so that string can pass through, suggesting that they were operated like marionettes. Part of the smallest figure fits neatly inside the hollow torso of another and was possibly used to represent birth.

All five ceramic figurines lay near the top of the pyramid, less than half a meter below its apex. Three are about 30cm tall, while the other two measure 18cm and 10cm. The larger figures are unclothed and feature movable heads with open mouths, allowing dynamic expressions during performances.

“They are clay actors...When you hold them in your hand, sometimes they even look creepy because of their vivid expressions,” Jan Szymanski, co-author of the study, told Science magazine.

Researchers first discovered the puppets in 2022. At first, they thought the figurines were part of a burial offering, but the lack of human remains nearby suggested that instead, they served for public rituals or displays. Archaeologists have found similar figurines in Guatemala.

It seems that El Salvador was not as isolated as researchers have suspected until now. Similar items cropping up in various countries suggest a cultural interexchange or shared tradition among ancient Mesoamerican communities.

At White Sands National Park in New Mexico, archaeologists identified 20,000-year-old human footprints and parallel drag marks that they believe were left by a travois.

A travois is a simple wooden frame made from two intersecting poles bound together in an A or X shape. Heavy loads rest on the frame, which a person then drags behind them. This new finding is the earliest proof of human transportation technology in the Americas.

Indigenous people in the Great Plains regularly used travois to haul their goods and tents around. While dogs or horses pulled more modern travois, the ancient tracks at White Sands indicate a time when humans themselves dragged them from place to place. Modern indigenous people from the region agree with these conclusions.

A shopping cart minus the wheels

The presence of both adult and children's footprints beside the drag marks paints a vivid picture of prehistoric family life. Adults transported the belongings while kids walked nearby. Matthew Bennett, the lead author of the study, likened it to the modern use of shopping carts.

"Many people are familiar with pushing a shopping trolley around a supermarket...with children hanging on," he said. "This appears to be the ancient equivalent, but without wheels.”

We know that our earliest ancestors must have used some form of transportation to carry their possessions, but any wooden vehicles have long rotted away.

"These drag marks give us the first indication of how they moved heavy, bulky loads around before wheeled vehicles existed," says Bennett.

The team began excavating the site four years ago. In 2023, they dated footprints to somewhere between 21,000 and 23,000 years ago. If they are correct -- there remains some debate around the topic -- then humans arrived in North America a few thousand years earlier than we've believed.

The drag marks, some of which extended over 50 meters, were preserved in dried mud and buried under sediment. Some were single lines, others two parallel lines very close together. The team thinks this shows the two types of travois used by the ancient humans. The single lines show the tracks made by an A-shaped frame. The parallel lines show tracks made by an X-shaped frame.