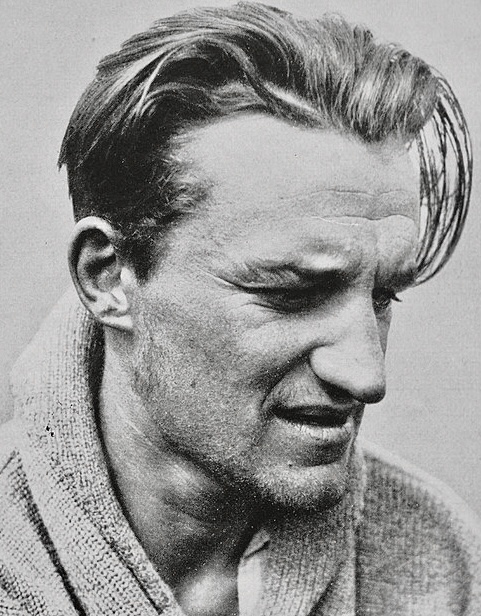

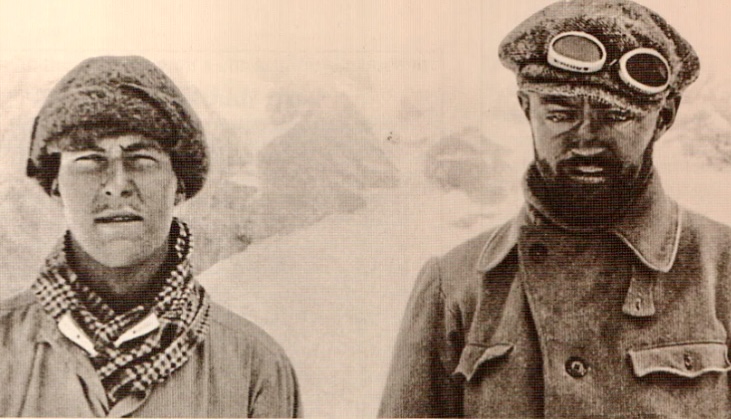

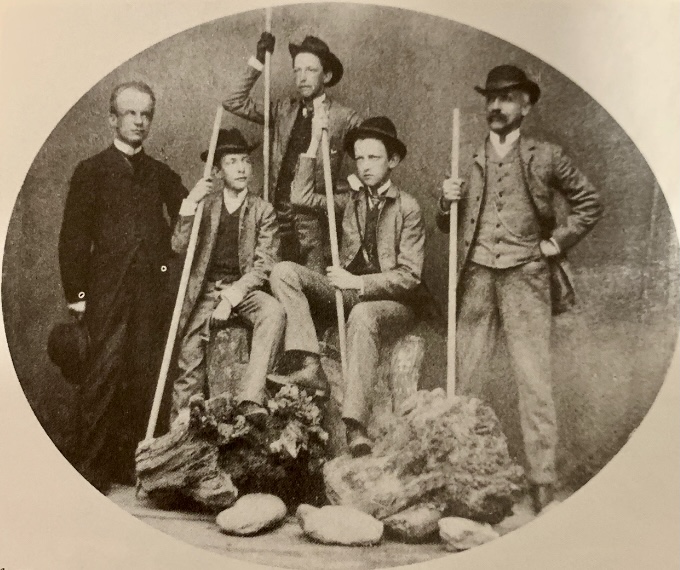

Today, July 25, would be the 104th birthday of Lionel Terray. The celebrated French alpinist climbed routes from the Alps to the Himalaya to the Andes, and also wrote one of the all-time great mountaineering books, Conquistadors of the Useless.

Early years

Lionel Terray was born on July 25, 1921. Growing up in Grenoble near the French Alps, Terray discovered mountaineering and skiing as a child. A conversation with his mother, who dismissed climbing as a stupid sport involving scaling rocks with your hands and feet, sparked his curiosity.

By age 12, Terray was climbing peaks like the Aiguille du Belvedere and the Aiguille d’Argentiere with his cousin. By 13, the talented youngster was leading climbs. But Terray’s love for the mountains caused problems; he got kicked out of one boarding school and ran away from another to pursue ski racing. With little family support, he got by on his own. Skiing was Terray’s first love, and as a teen, he won prizes in competitions, which gave him some money.

In 1941, during World War II, Terray joined Jeunesse et Montagne, a military program that kept him in the mountains. There, he met lifelong friends and climbing partners Gaston Rebuffat and Louis Lachenal.

In 1942, Terray carried out the first ascent of the west side of Aiguille Purtscheller. He also climbed the difficult Col du Caiman. From 1943 to 1944, Terray served in a high-mountain military unit. In 1944, he joined the French resistance, using his mountain skills against the Nazis.

Terray knocked off other notable first ascents, such as the east-northeast spur of the Pain de Sucre and the north face of Aiguille des Pelerins with Maurice Herzog in 1944.

A rising star

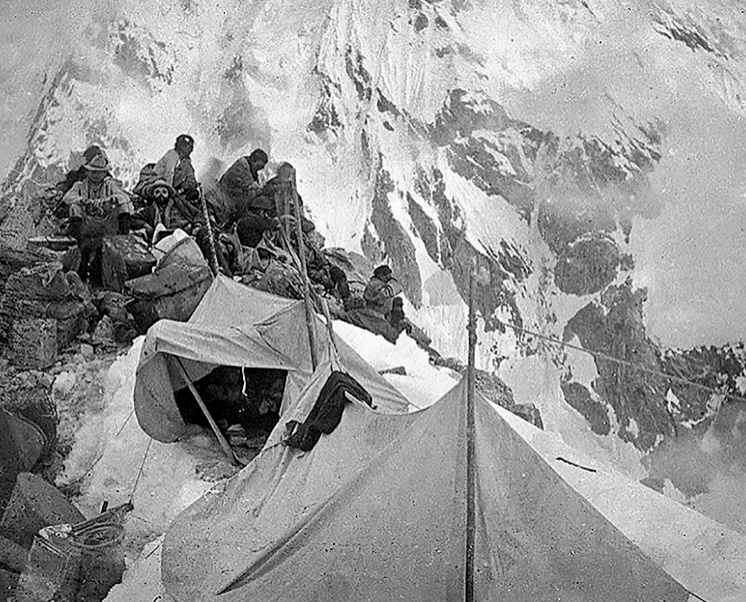

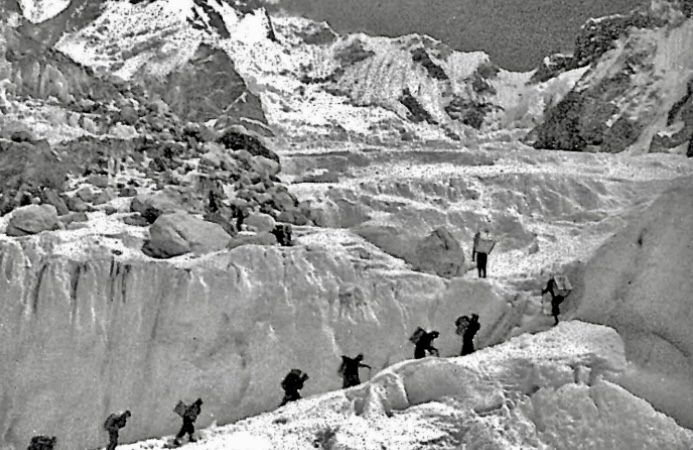

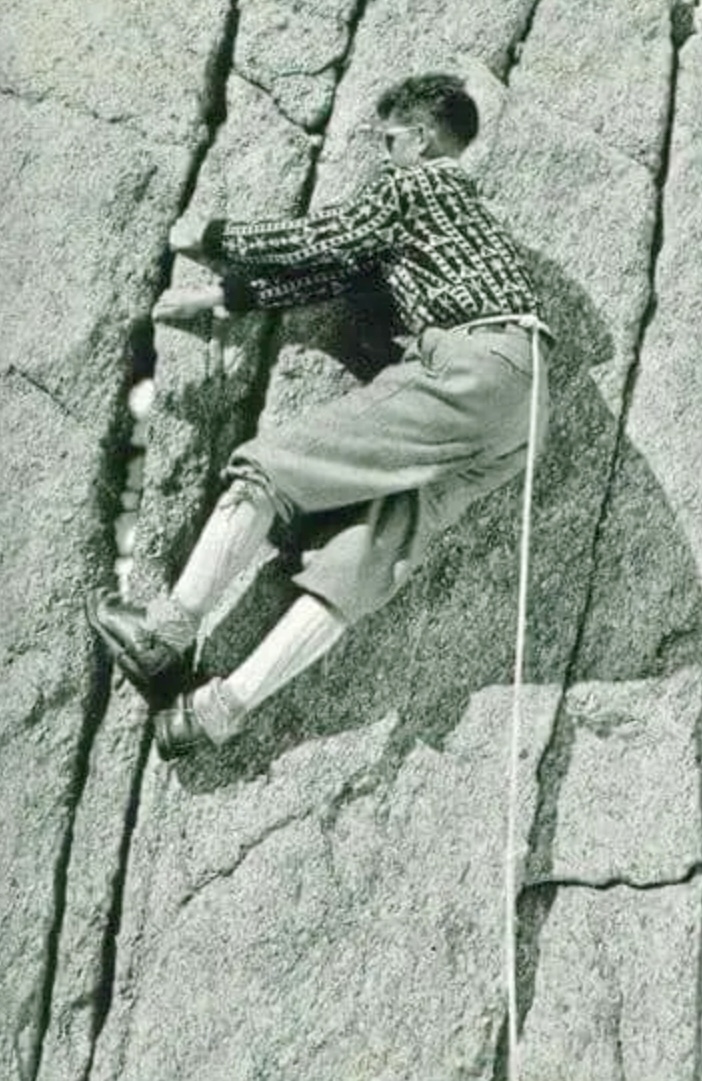

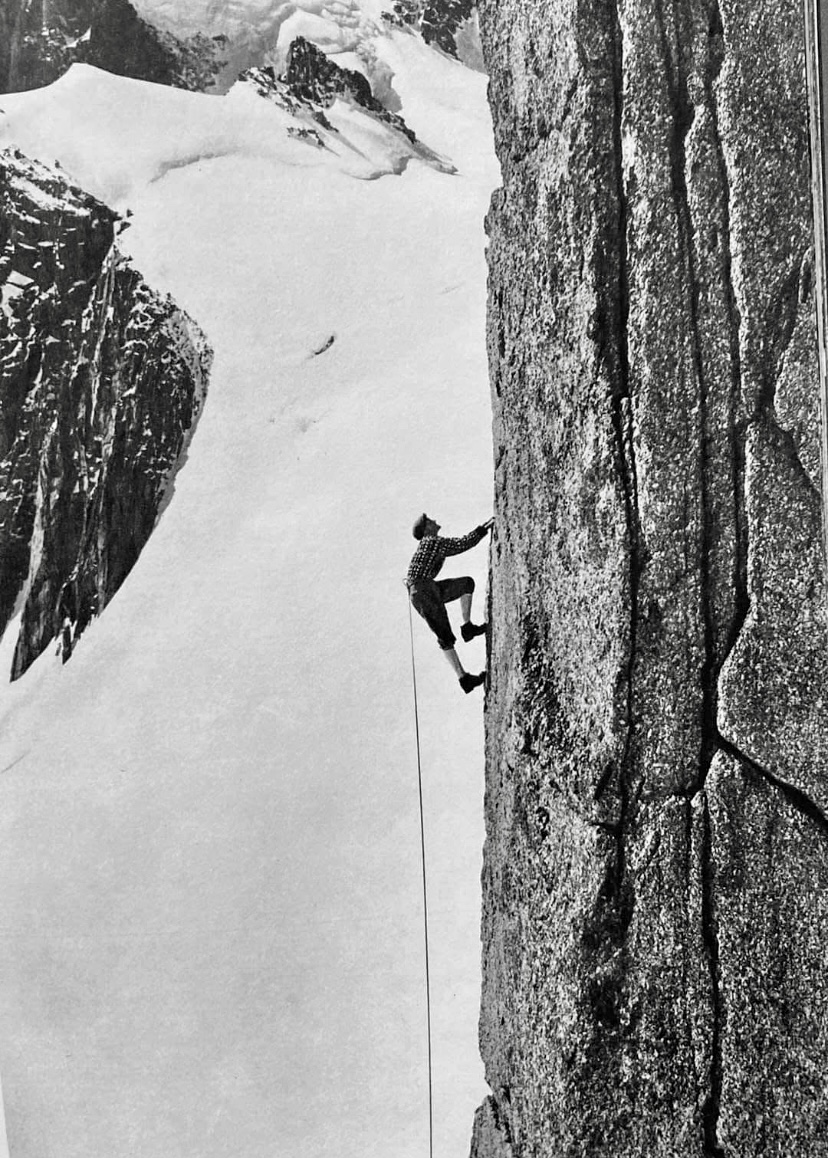

After the war, Terray became a mountaineering instructor and settled in Chamonix as a freelance guide. With Lachenal, he did some of the Alps’ most difficult routes, including the Droites’ north spur in only eight hours in 1946, the Walker Spur of the Grandes Jorasses in 1946, the northeast face of Piz Badile, and the north face of the Eiger in 1947 (the second-ever ascent). Terray's speed and skill earned him a reputation as a climbing prodigy.

A rescue attempt on Mont Blanc

In late December 1956, Lionel Terray took part in a rescue attempt on Mont Blanc’s Grand Plateau. At about 4,000m, young climbers Jean Vincendon and Francois Henry were stranded after a failed attempt on the Gouter Route, a popular 1,800m climb to Mont Blanc’s summit.

On December 22, a blizzard caught Vincendon and Henry near the Vallot Hut at 4,362m. Freezing and frostbitten, they couldn’t descend. Terray, now a Chamonix guide, defied the Compagnie des Guides’ decision to postpone a rescue because of the extreme risks of strong winds and freezing temperatures.

Terray’s team battled brutal weather for two days but couldn’t reach the climbers. A military helicopter, attempting a parallel rescue, crashed near the Vallot Hut, stranding its crew. Terray’s group retreated, exhausted, as conditions worsened.

French Army instructors finally reached Vincendon and Henry in early January, but found them near death from exposure and frostbite. Evacuation was impossible, and both climbers died.

Terray’s rescue effort led to his expulsion from the guides’ organization, sparking controversy in Chamonix.

Eiger rescue

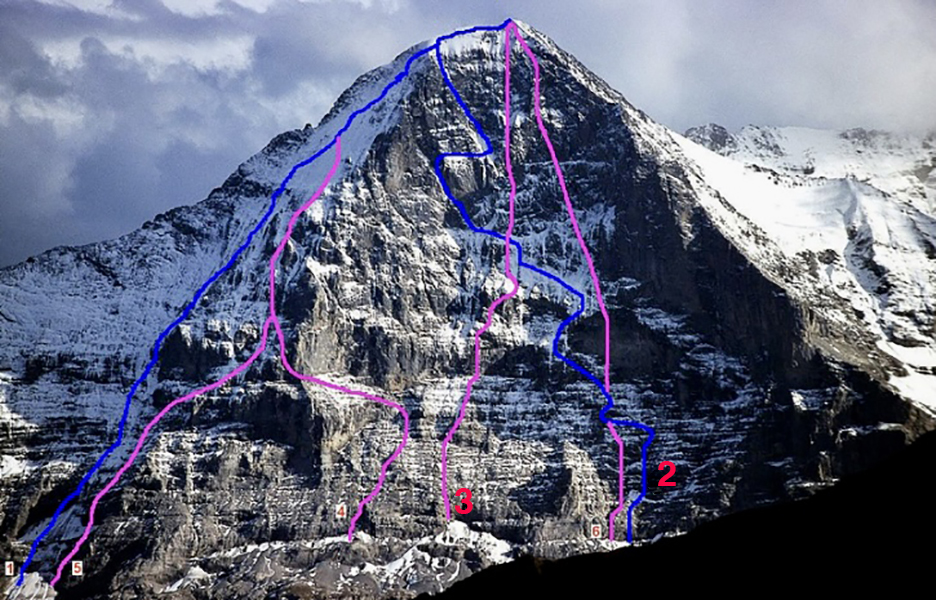

In the summer of 1957, Terray took part in a complicated rescue on the Eiger’s North Face in the Swiss Alps. Two Italian climbers, Claudio Corti and Stefano Longhi, were stranded after an avalanche hit their team during an attempt on the notorious Nordwand. The route, known for its steep ice, rockfall, and brutal weather, had already killed their partners, and Corti was injured.

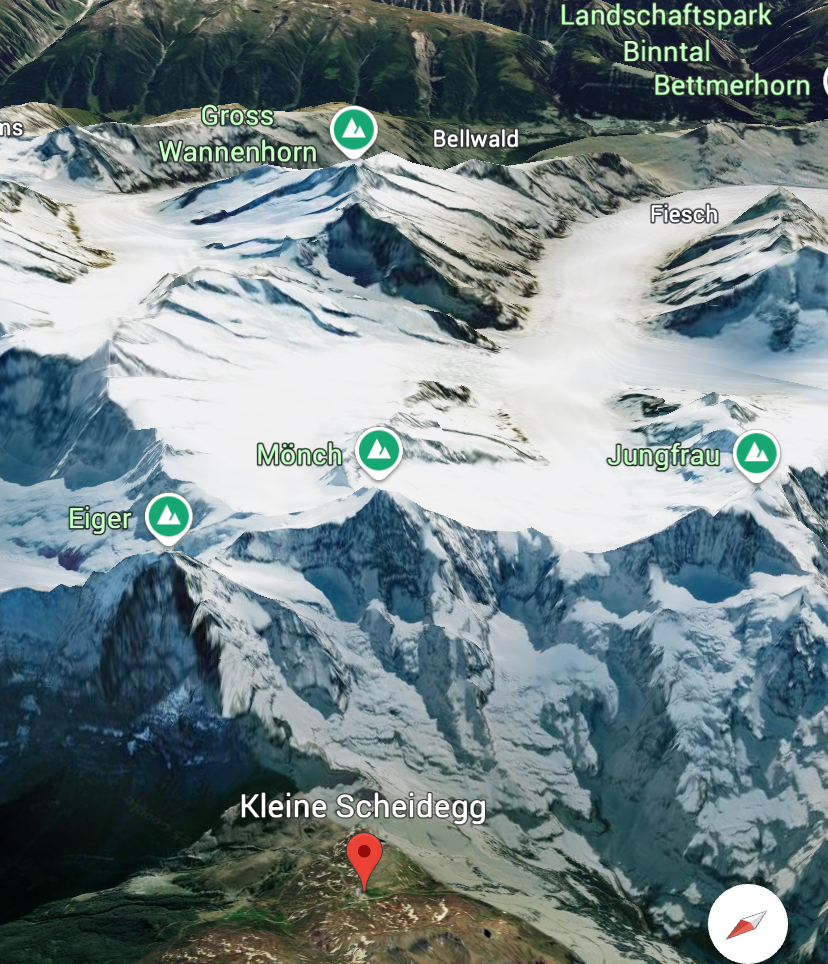

Terray, then 35, joined a multinational rescue team at Kleine Scheidegg. The climbers were stuck near the Difficult Crack, at around 3,300m. Terray, with German climbers Wolfgang Stefan and Hans Ratay, ascended via ropes and pitons. They battled harsh winds and -20°C temperatures. After two days, they reached Corti, who was hypothermic but alive, clinging to a ledge. Longhi, lower down, was too weak to move. Terray secured Corti with ropes, and the team lowered him 600m to safety. Longhi, barely conscious, died during the descent when his rope jammed.

The effort, involving 50 people, was one of mountaineering’s greatest rescues.

Other historic climbs

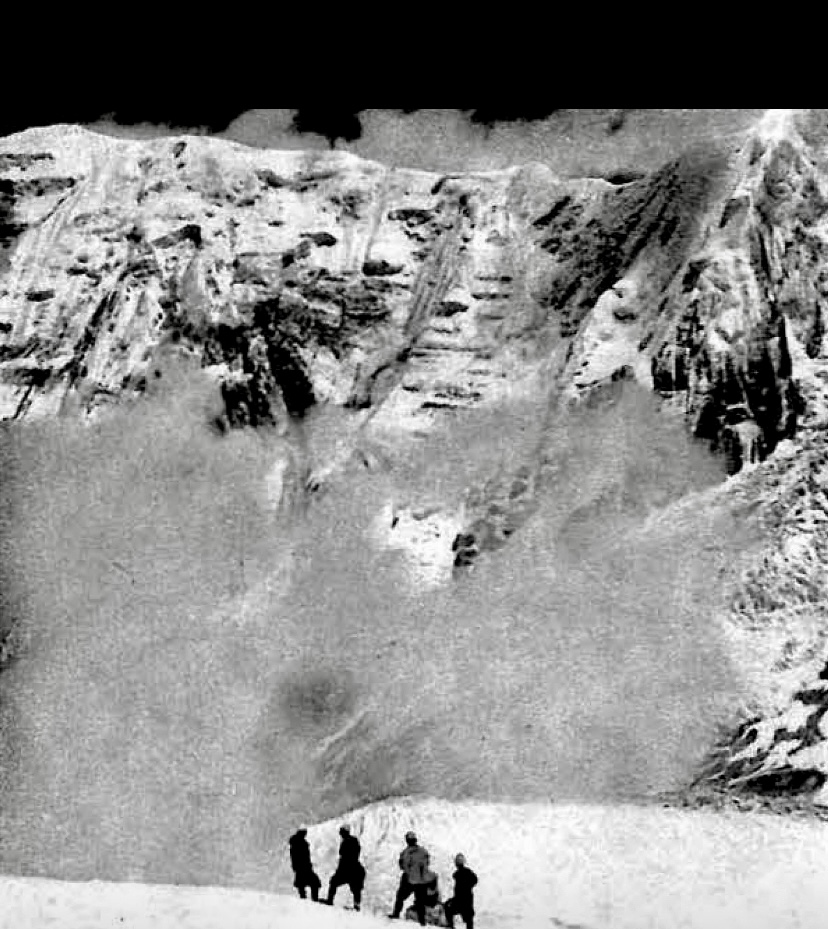

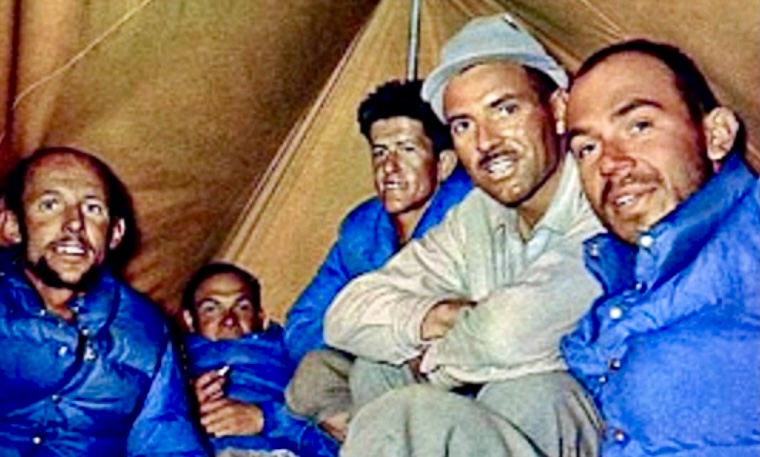

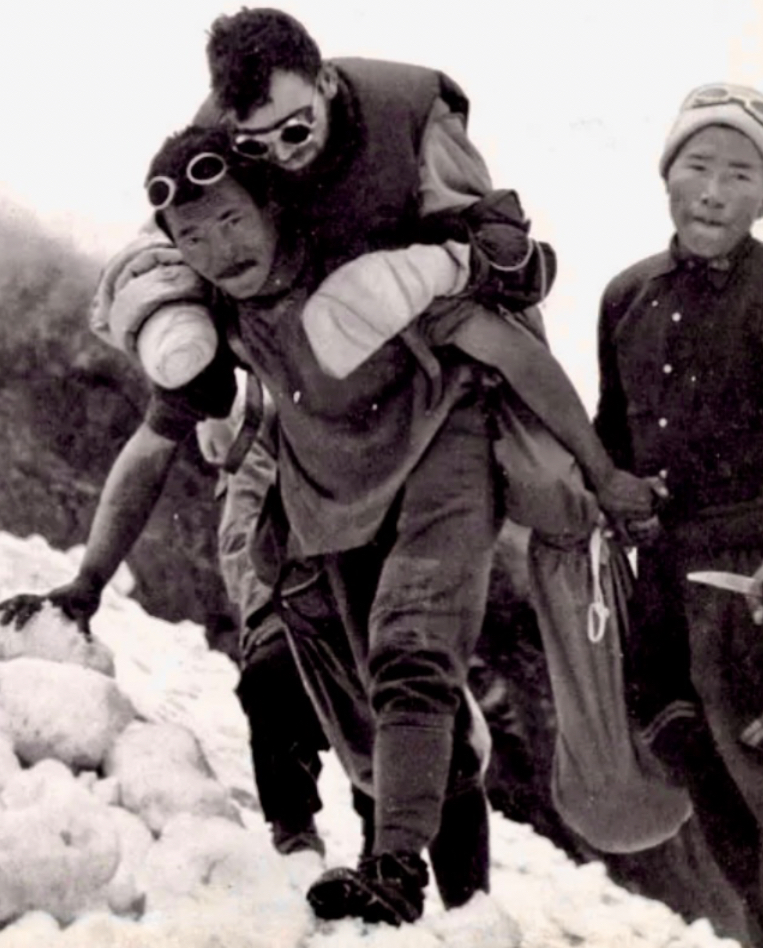

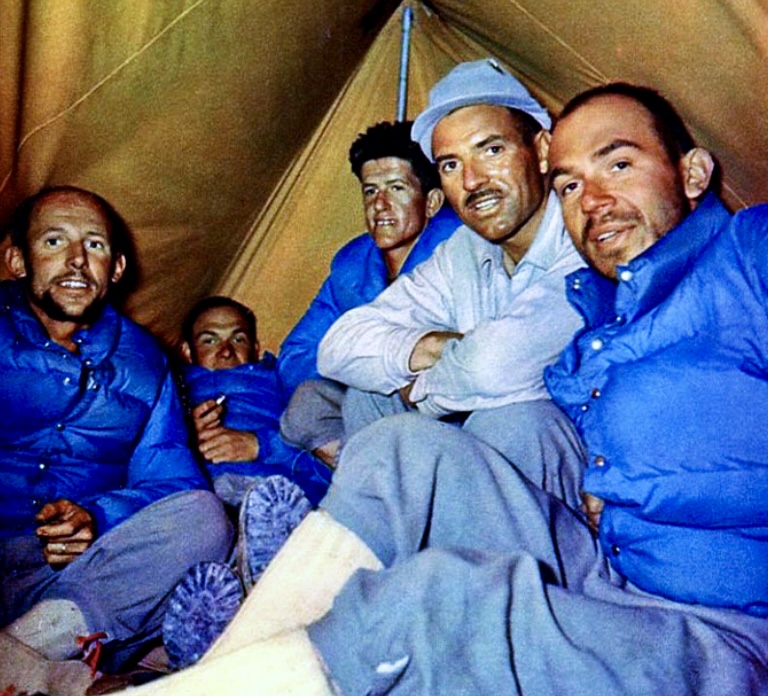

Terray’s ambition took him beyond the Alps. In 1950, he joined Maurice Herzog’s expedition to 8,091m Annapurna I in the Himalaya, the first confirmed ascent of an 8,000m peak. Terray and Rebuffat's efforts, alongside one of the Sherpas, were crucial to helping the frostbitten Herzog and Lachenal descend safely. The climb brought global fame for the French team.

In 1952, Terray and Guido Magnone made the first ascent of Cerro Fitz Roy in Patagonia. That year, Terray also climbed 6,369m Huantsan in Peru with Cees Egeler and Tom De Booy.

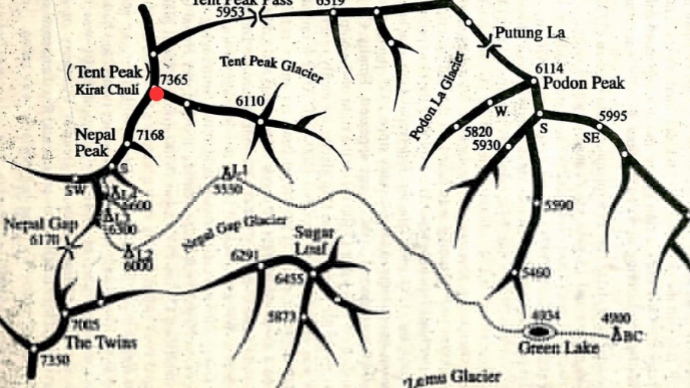

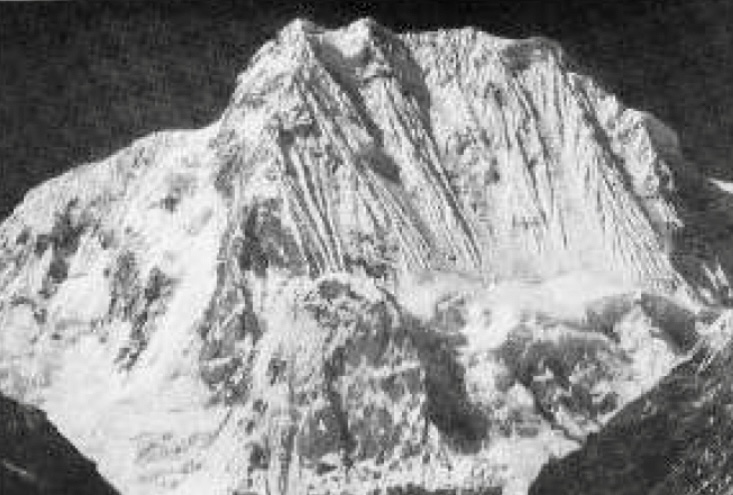

In 1954, Terray summited 7,804m Chomo Lonzo with Jean Couzy, paving the way for their legendary 1955 first ascent of 8,485m Makalu. In 1962, Terray led the first ascent of 7,710m Jannu in Nepal, and in the summer of 1964, he led the first ascent of 3,731m Mount Huntington in Alaska.

In Peru, Terray made first ascents of peaks like 6,108m Chacraraju, considered the hardest peak in the Andes at the time, along with 5,350m Willka Wiqi, 5,428m Soray, and 5,830m Tawllirahu.

Conquistadors of the Useless

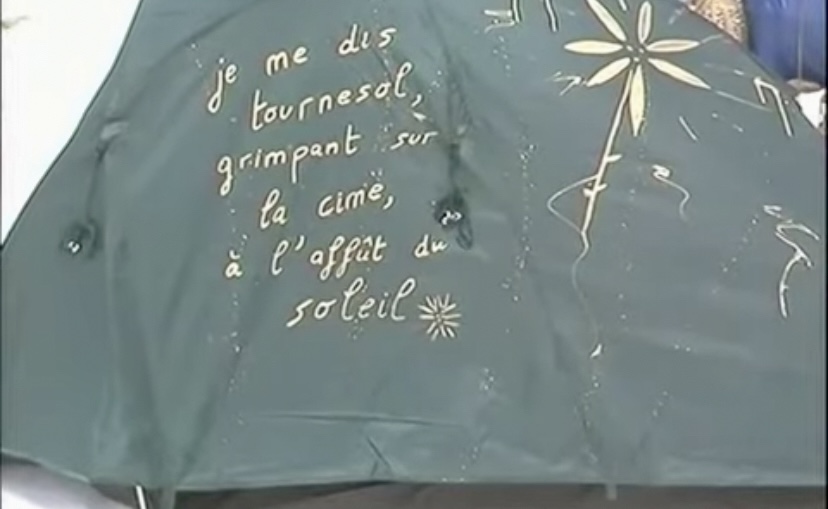

In 1961, Terray published Les Conquerants de l’inutile (Conquistadors of the Useless), a memoir that blends vivid accounts of his climbs with reflections on the purpose of mountaineering. The title captures his view that climbing, though seen as pointless by some, was a noble pursuit. The book, translated into several languages, remains a classic.

A tragic end

On September 19, 1965, Terray and his friend Marc Martinetti died in a climbing accident in the Vercors massif near Grenoble. Terray was just 44.

The pair was descending the Gerbier, a limestone cliff in the Vercors range, after completing a route. They were roped together when their rope -- likely weakened or damaged -- snapped. They fell more than 200m to the base of the cliff. Both climbers died on impact. Chamonix mourned deeply, and his funeral drew figures like Herzog, Rebuffat, and Leo LeBon.

"He was to many a great and dear friend, and all those who paid him tribute before he was laid to rest in the Chamonix Cemetery, among them hardened mountain climbers, wept like small children. To the French climbing world, especially the younger generation, his absence represents an irreplaceable loss, as he was the hero of their dreams, and could hold an audience breathless as no one ever has been able to," Lebon wrote in the American Alpine Journal.

Terray’s legacy lives on through his climbs, rescues, and writings. His son, Nicolas, is a mountain guide. Known for his red beanie and sunglasses, Terray appeared in films like Etoile du Midi, La Grande Descente, and Stars Above Mont Blanc.

You can watch Etoile du Midi below, with the option of automatic subtitles:

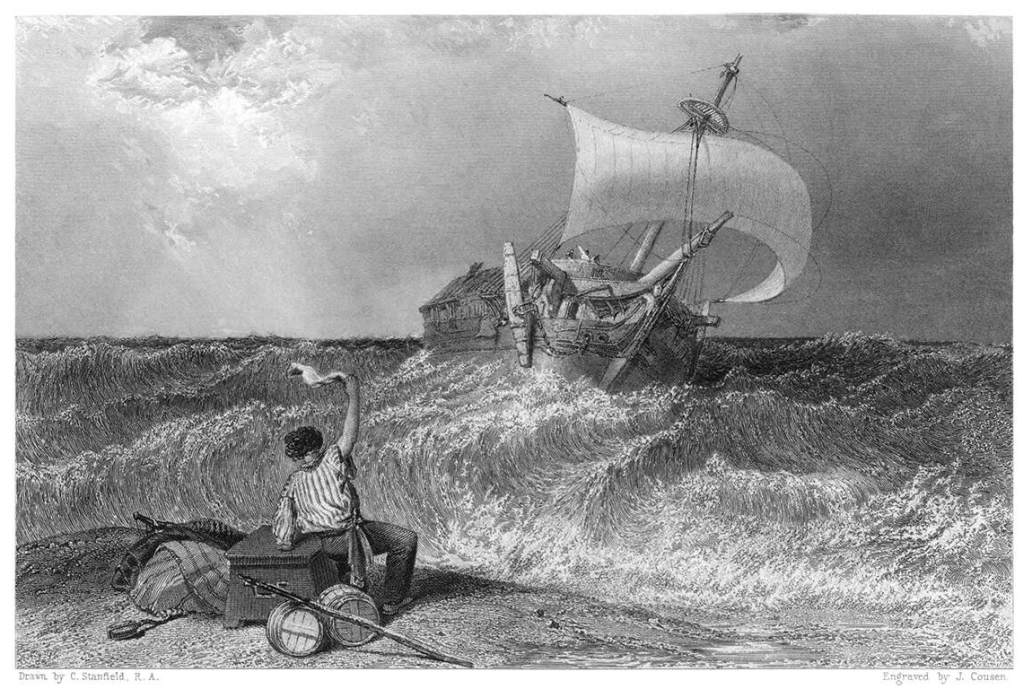

In May of 1622, the English East India Company ship Tryall became the first English ship to sight the coast of Australia. Shortly after, it became the first ship to sink off the coast of Australia.

The story of the Australia's oldest shipwreck covers 400 years, from a suspicious sinking to a pair of castaway journeys, a court case, a geographical mystery, and a modern scandal involving the misuse of explosives at an archaeological site.

The maiden launch of the Tryall

The Tryall (also spelled Triall, Tryal and Trial) set sail from Plymouth on Sept. 4, 1621. She was a British East Indiaman, a mercantile vessel built to travel between England and the Global Southeast, then called the East Indies.

Owned by the British East India Company, her generous hold was filled with textiles, silver, and supplies bound for Batavia -- present-day Jakarta, Indonesia. This was to be her maiden voyage, and an inspection by EIC officials at the docks found her in good condition.

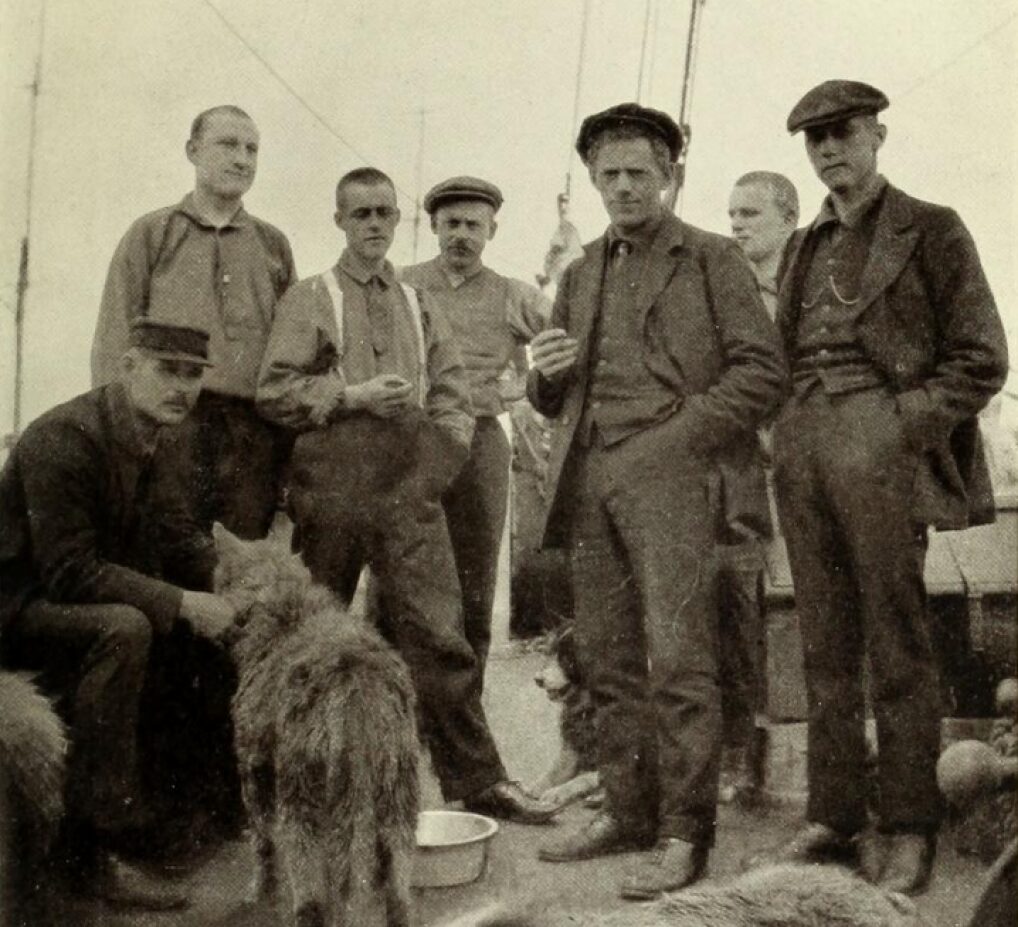

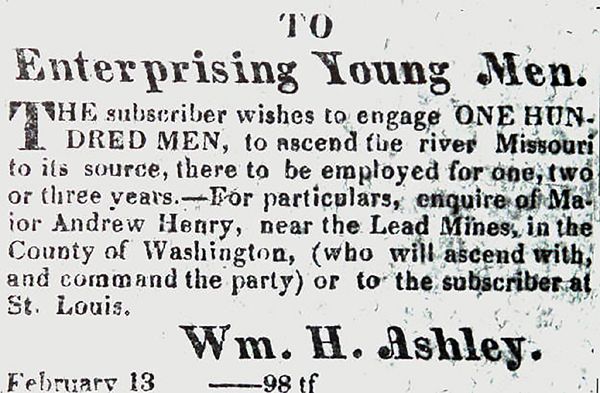

Her Captain was John Brookes. The other key man aboard was Thomas Bright, the EIC's representative, or "factor" for the voyage. One hundred and forty-three seamen rounded out the crew, and after a brief pay dispute, they sailed for the Cape of Good Hope.

This stage of the journey went fine. They arrived at the tip of Africa, took on fresh supplies, and set off for Batavia on March 19. By a new, dangerous route.

Another way to India

At the turn of the 17th century, the standard route from Cape Town to Batavia came from 15th-century Portuguese explorers, who used the seasonal monsoon winds to cross the Indian Ocean. It took about 12 months.

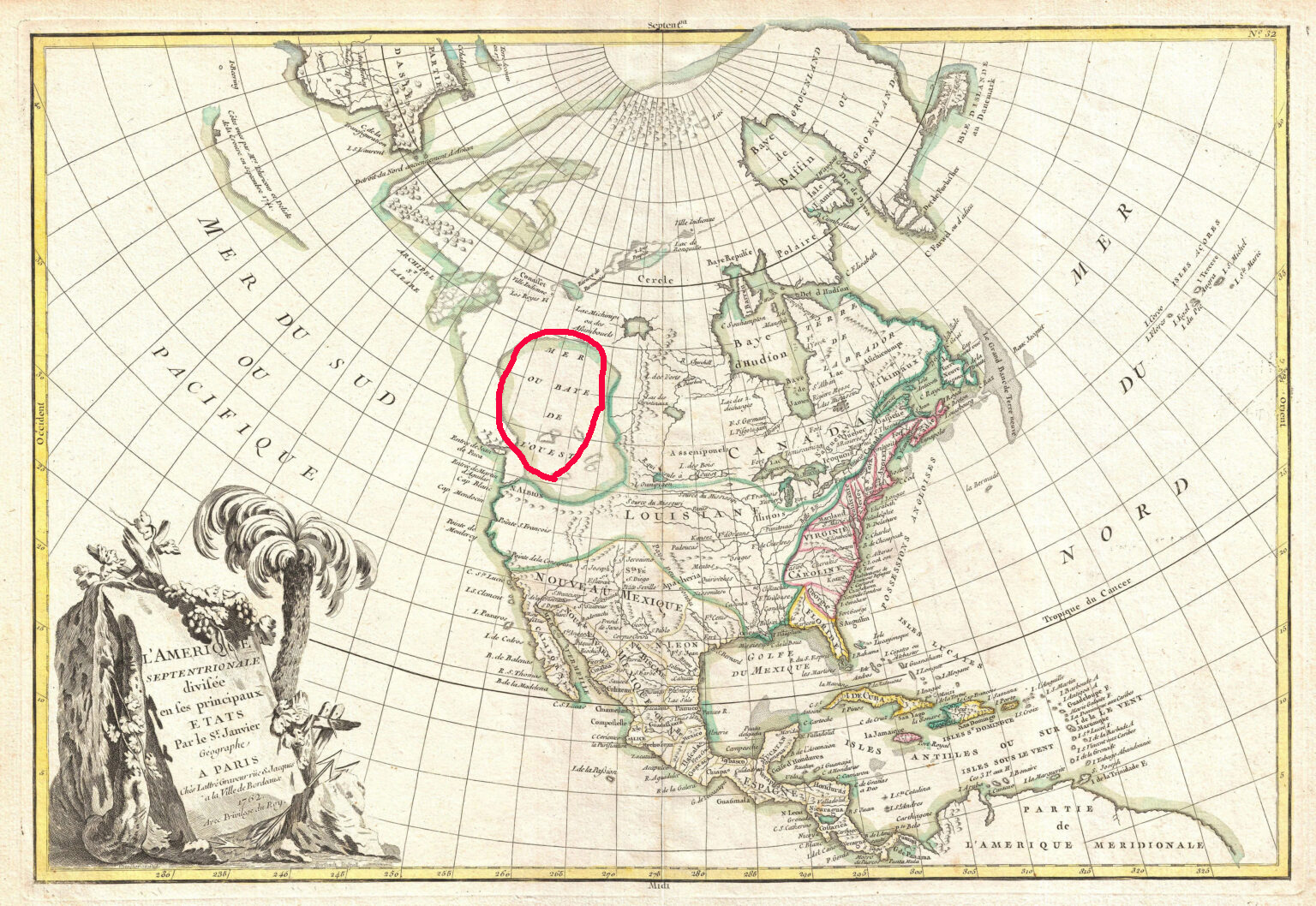

The Dutch decided that if they were going to steal the spice trade from Portugal, they had to do better than that. So Hendrik Brouwer took an alternative way in 1611. It became known as the Brouwer route.

The new route cut travel time in half by ducking down into the Roaring Forties and using their strong westerly winds to cross the Indian Ocean. The key was the timing of that northeast turn. Too early, and you'd end up in the middle of the Indian Ocean. Too late, and you'd crash into Australia.

They didn't know that yet, though. A few Dutch explorers had sighted some islands off the Australian mainland, but no one suspected a whole continent might be in the way.

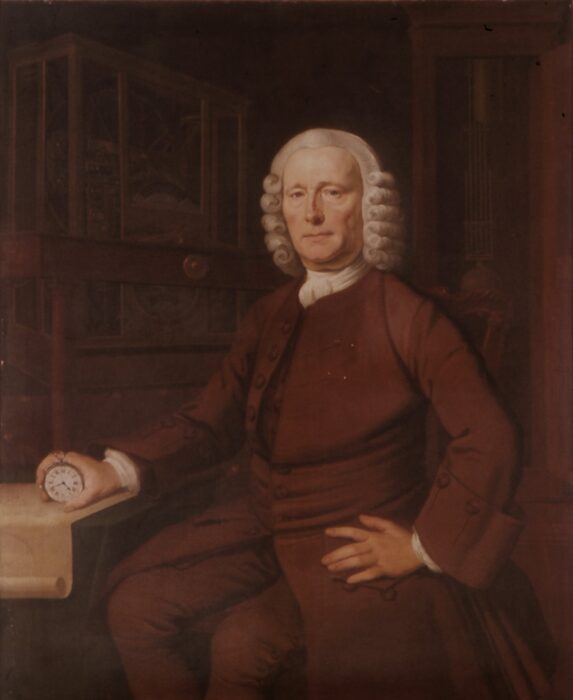

The problem with that all-important turn is that, at the time, there was no good way to determine longitude at sea. Ships would have to make the turn using dead reckoning, which is a fancy nautical term for "guessing." In 1620, the British EIC decided to copy the Dutch and sent Captain Humphrey Fitzherbert to test the route.

He had a great time and gave it a thumbs-up, so they gave Captain Brookes a copy of Fitzherbert's journal and told him to do the same thing.

The wreck of the Tryall

Brookes was nervous about the new route. In Cape Town, he met Captain Bickell, another EIC Captain. He asked Bickell if he could borrow one of his experienced mates to help navigate, and Bickell gave him permission. But Bickell's ship, the Charles, was on its way home, and none of her mates were willing to delay their return to help.

Brookes had to sail on, with only the 1620 journal and imperfect charts as a guide. The Tryall descended to 39 degrees latitude, and the Roaring Forties drove them east.

On May 1, they spotted land. They had just become the first Englishmen to see Australia. Brookes and Bright both describe a great island, because from their perspective, a pair of points made the coast look like an island. Brookes turned north for the run up to Java, but was kept in place by contrary winds. Finally, on May 24, he was able to head north.

The next day, late in the evening, in calm seas, the Tryall struck rocks. Brookes ran up on deck, giving orders to tack west, hoping to dislodge her. A strong, brisk wind began to blow as water flooded into the ship, the sharp rocks tearing her timbers apart. It was too late, Brookes realized, to save her. He "made all ye meanes I could to save my life and as manie of my compa[ny] as I could."

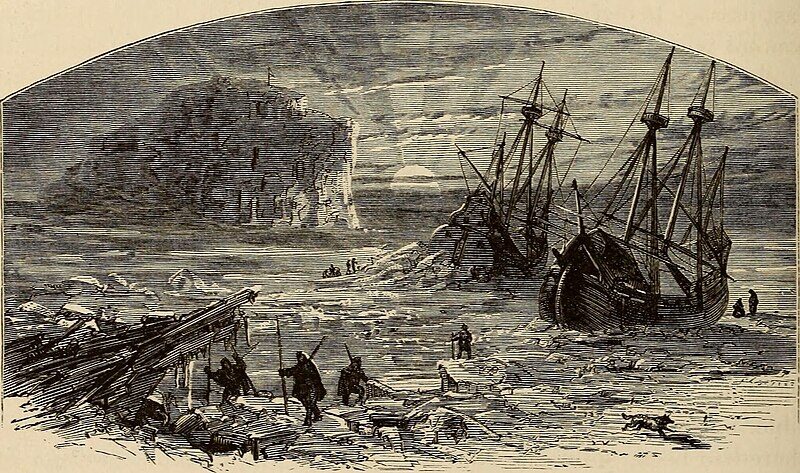

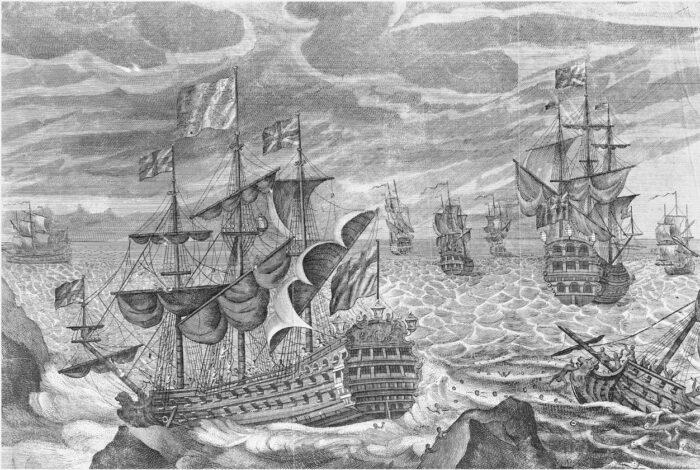

He launched the ship's two boats. Ten, including Brookes, climbed into the skiff, while 36, including Thomas Bright, piled into the pinnace. Less than six hours after striking rocks, the fore-part of the Tryall broke up. Ninety-seven died.

Brookes' story

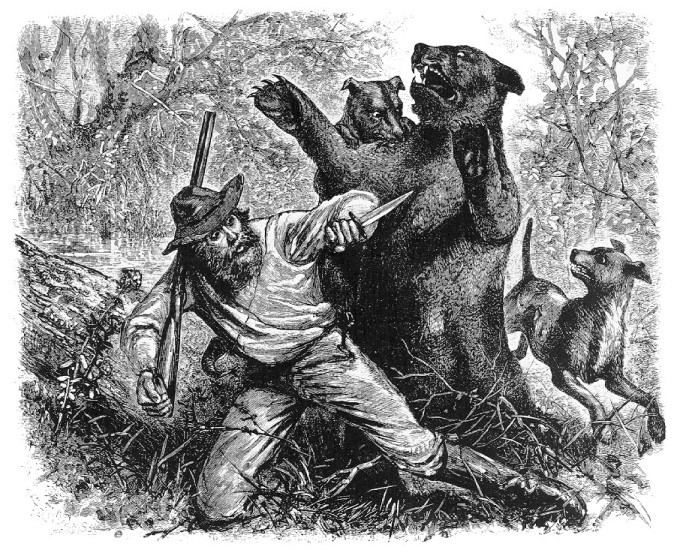

Brookes' skiff launched first. With him were nine sailors and a cabin boy, who would definitely be eaten first if it came to cannibalism. They had several cases of spirits and kegs of water, but only four pounds of bread. They landed briefly on a low island, now known to be Barrow Island, then set off again.

On July 5, they arrived in Batavia, and Brookes sent his report to his EIC superiors. Fitzherbert must have overlooked the land they sighted on May 1, he explained. "He went 10 leagues to ye Southwardes of this iland," Brookes asserted, before making the northeast by east turn. Brookes said that after sighting this land, he also made a northeast by east turn.

That Fitzherbert had missed the rocks was pure chance; his ships had sailed right past destruction without realizing it. The wreck of the Tryall could have happened to anyone. The EIC agreed. So they gave him another ship, the Little Rose, to explore the area around Sumatra. When he got back, they put him in charge of the Moone.

The wreck of the Moone

Brookes was taking the Moone back to England with a few other EIC vessels. But the Moone was wrecked off the coast of Dover, and with her went £55,000 worth of cargo, about $14,000,000 today. John Brookes and the ship's master, Churchman, began accusing each other of misconduct, and the EIC threw them into prison.

In court, Brookes made multiple lengthy speeches protesting his innocence. He also stressed, once again, that the Tryall wreck was not his fault. Regarding the Moone, Brookes blamed the ship's poor condition, calling it worm-infested and half rotten.

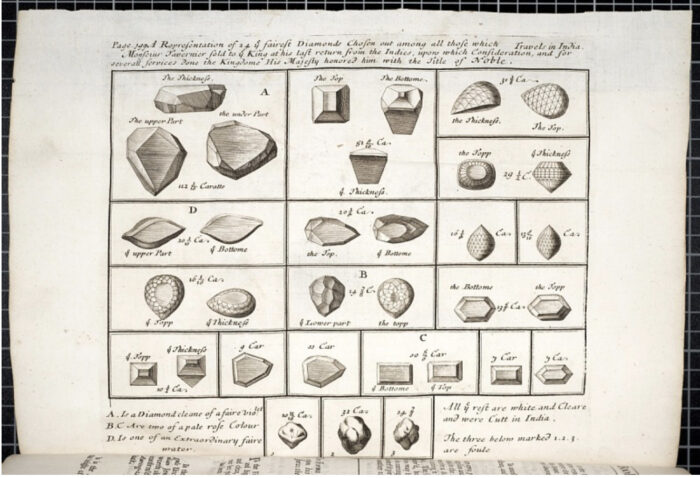

Witnesses, however, testified that he had discussed deliberately sinking the ship back in Cape Town. He was accused of deliberately sinking the ship in an elaborate heist of the valuable cargo. In fact, when the wreck site was examined, most of the cargo was missing. Multiple eyewitnesses also claimed Brookes had used the confusion of the sinking to break open and pilfer a chest of jewels.

The court case dragged on for years before finally being settled out of court. While he was never convicted, Brookes had lost all of his money and reputation. But with all the back and forth about stolen diamonds and the Moone, his claims about the Tryall went unchallenged. There was one man, however, willing to challenge John Brookes: Thomas Bright.

Bright's story

In a series of letters, Thomas Bright gave his side of the story. The fact that they'd hit the rocks at all, he claimed, was due to Brookes not keeping a proper lookout. Once the ship was struck, he described Brookes rushing to provision his own boat. He even personally betrayed Bright ("like a Judasse") by promising to take him, then launching the skiff while Bright wasn't looking. The skiff then made straight for Java without waiting to see what became of everyone else.

The pinnace, or longboat, launched an hour and a half after the skiff, with 36 men aboard. They had a couple of pounds of bread, some bottles of wine, and a single barrel of water. The sea was too rough to do anything but keep in sight of the crumpling ship, weathering the waves, until morning. In daylight, they made for a nearby island.

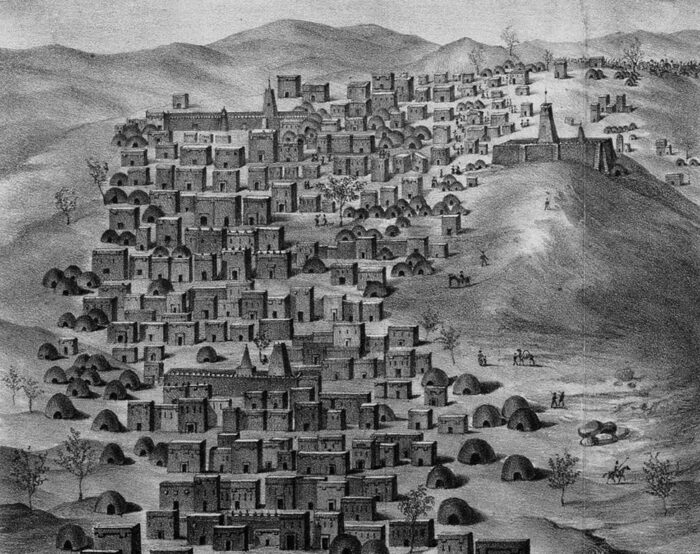

They spent a week on a low, uninhabited island, now known as North West Island. There, they repaired the pinnace and tried to stock up on provisions for the journey ahead. Bright kept himself busy drawing maps and charts of the surrounding area, becoming the first Englishman to map parts of Australia.

The pinnace successfully reached Java in late July. Bright was furious at Brookes and the lies he had been spreading. He wrote detailed letters and drew maps and charts laying out Brookes' deception -- but they went unheeded, and then were lost.

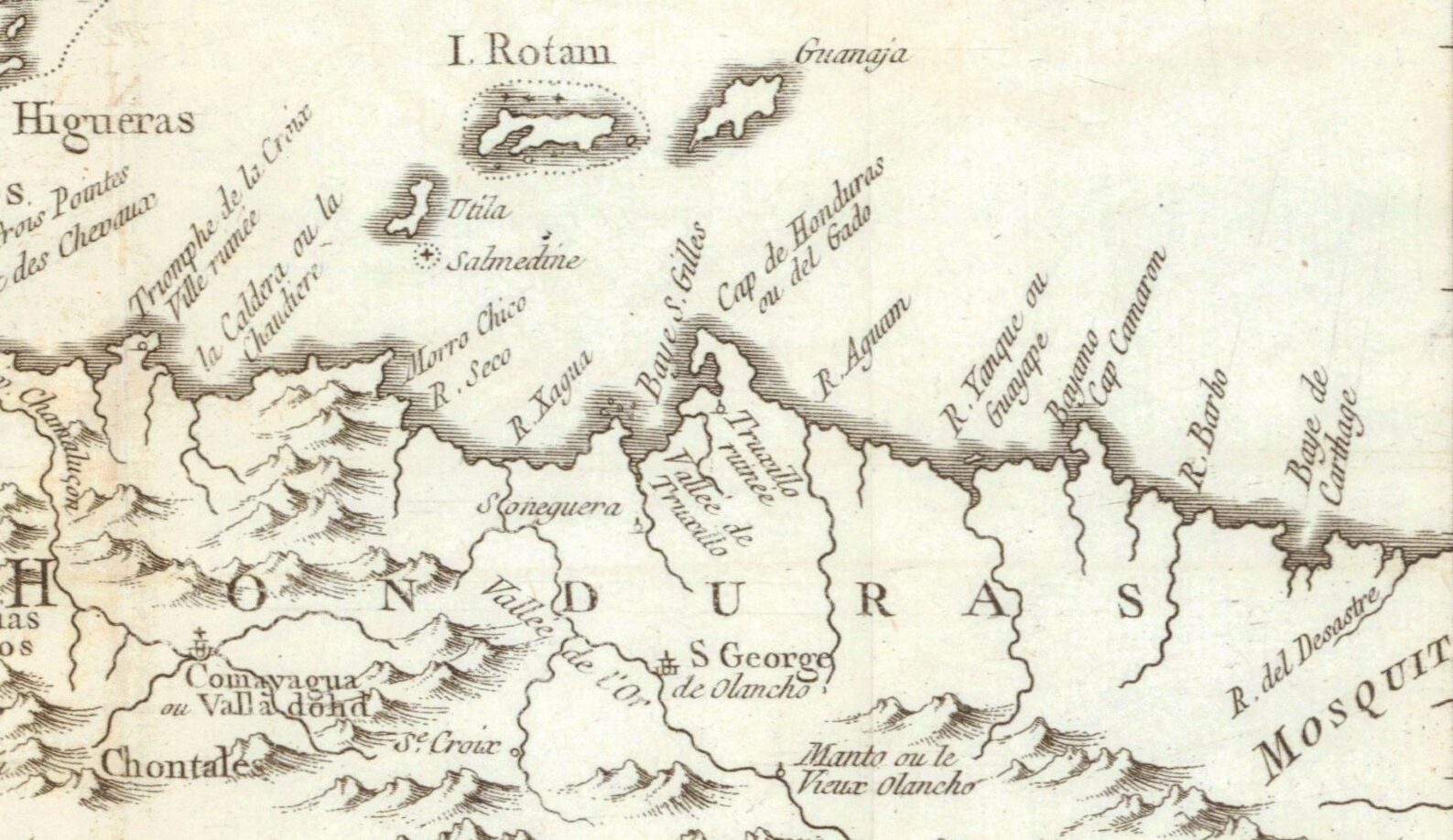

The search for the Trial Rocks

Both the British and Dutch East India Companies (referred to as EIC and VOC, respectively) were concerned that their trade route had secret, deadly rocks somewhere along it. Brookes advised the company to avoid going too far south, theoretically avoiding the Trial Rocks but also reducing speed.

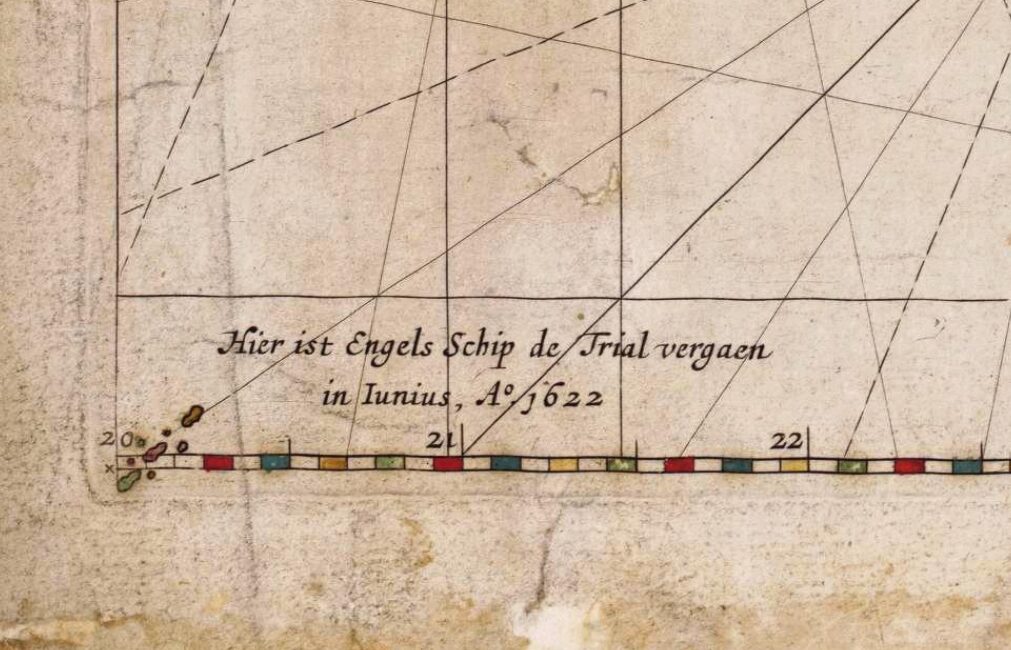

In 1636, the VOC sent a pair of ships under Gerrit Tomaszoon Pool. His instructions included "trying in passing to touch at the Trials," to gather information about their exact location. But he didn't find them.

As the years went on, sailors and mapmakers alike were confused as to where the rocks were and whether they existed. By 1705, the Commodore of the Dutch Ships reportedly didn't believe they were real, at least not in the position Brookes had indicated.

By the late 18th century, even the story's origins were hazy. A 1780 directory of the East Indies claimed that the Trial Rocks were "discovered by a Dutch ship in 1719."

In 1803, English Captain Matthew Flinders took many soundings in the area on his way back from Timor. He spent weeks searching for the rocks despite the fact that illness was rampant aboard ship.

Finally, he concluded that "the Trial Rocks do not lie in the space comprehended between the latitudes 20° 15' and 21° South, and the longitudes 103° 25' and 106° 30' East." Thus concluded, they set sail, hoping to get better food for the sick, as "the diarrhoea on board was gaining ground."

His hard-won findings convinced the British Admiralty, which declared the Trial Rocks nonexistent.

The (re)finding of the Trial Rocks

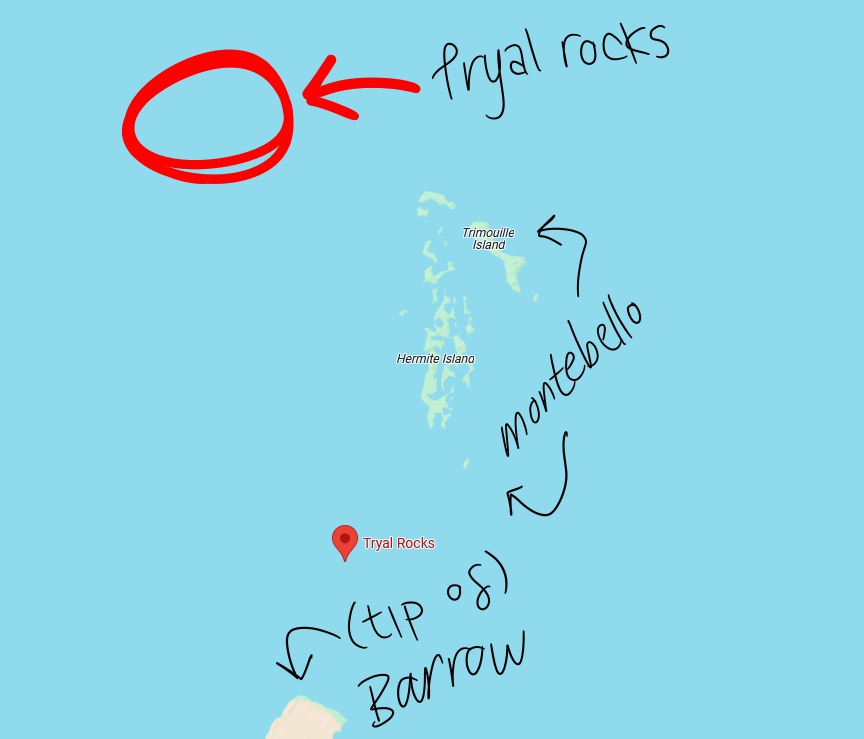

Today, we know that the Trial Rocks lie just off the Montebello Island group, off the coast of Western Australia. The definitive identification of the Trial Rocks came in fits and starts, being repeatedly made and then forgotten.

In 1818, the Greyhound had a run-in with the rocks, managing to avoid being sunk through luck and good spotting. As she was captained by one Thomas Richie, the rocks became known as Richie's Reef. Two years later, another brig passed through the area and had a look-see.

Aboard was Lt. Phillip Parker King, who recorded his belief that the Trial Rocks were, in fact, located around the area of Barrow Island and the Montebello Islands. The next Admiralty chart placed Richie's Reef to the northwest of Montebello, and a second, separate set of Trial Rocks between Montebello and Barrow. They were only wrong by 42 kilometers, which was at least an improvement.

Enter Australian historian Ida Lee. She uncovered the letters by Bright and Brookes and consulted Rupert Gould. Before he became really into the Loch Ness monster, Gould was a member of the Hydrographer's Department at the Admiralty, a respected expert on cartography and naval history.

He replied confidently: Richie's Reef was the Trial Rocks, and Captain Brookes had intentionally deceived everyone about where the rocks lay.

Captain Brookes' great deception

Have you ever really messed up at work? I mean really, really messed up? Imagine if you messed up so bad that nearly a hundred people had died and a huge ship full of valuable trade goods had been lost. Would you lie about it? Be honest.

The truth was that the rocks hadn't been anywhere along the Brouwer route. Brookes had gone too far east, overshooting his turn so badly that they'd sailed right into the coast of Australia. Realizing he went too far, Brookes then headed directly north, instead of northeast, running into the Trial Rocks.

When it came time to write his account, he claimed to have turned earlier and been headed northeast. He told the same lie about the skiff journey, claiming to have traveled northeast instead of east. If he had actually traveled northeast from the Trial Rocks, he would've missed Java entirely.

Brookes had lied about where the rocks were to disguise his mistake, claiming they were hundreds of kilometers west of their actual position. This was not an innocent deception. As the men who died on the Tryall could tell you, knowing where hidden rocks lay was a matter of life and death.

Bright had tried to get the real story out in his letter. But that had been lost to the depths of the archives until Ida Lee. In 1934, Lee published her article, and henceforth, the rocks were placed in the correct location. Except, apparently, on Google Maps, which inexplicably gives the pre-1934 location.

The Tryall gets blown up

No one actually went looking for the wreck until the late 1960s. Two men from a group called the Underwater Explorers Club, John MacPherson and Eric Christiansen, got Gould's report from the Admiralty Hydrographic Office. A few years later, Christiansen led a small party of divers to the wreck site. For our purposes, the most important member of this group was Alan Robinson.

They dove at the Trial Rocks in May 1969. On the southwestern side of the rocks, they found an old anchor, then another, and then cannons — it was a wreck site. They reported the find to the Western Australia Museum and collected a finder's fee equivalent to about $18,500.

The WA Museum organized an expedition, but poor weather prevented them from doing much diving. In 1971, they came back with more funding, but when they dove down to the site, they found it had been vandalized -- with explosives. The reef itself was damaged, along with some of the cannons and anchors, and the various smaller artifacts one would expect around the site were nowhere to be found.

The suspected culprit was Alan Robinson. A notorious figure in Australian maritime archaeology, Robinson was a treasure-hunter who frequently came into conflict with the laws around salvage and cultural artifacts. He was acquitted of the charges regarding the Tryall site, but we'll probably never know the truth.

Robinson died in jail while awaiting trial for attempting to murder his ex-wife, so was unable to confess about using blasting gelatin on Australia's first shipwreck.

An active archaeological site

Several more expeditions visited the damaged wreck site. Like many of the most famous Australian shipwrecks, any write-up of work on the Tryall site must mention the contributions of Dr. Jeremy Green. Green wrote the book on maritime archaeology, and by the discovery of the Tryall, had already led the investigations of the Batavia and Vergulde Draeck.

It was Green who led the 1971 dives and who gave the first tentative identification of the wreck as that of the Tryall. Because of all the missing artifacts, it's difficult to say beyond a shadow of a doubt that the ship found on Trial Rocks is really the Tryall. In addition to the location, Green used the cannons and anchors to confirm that they were looking at the remains of an English merchant ship from the early 17th century.

Subsequent dives have provided further evidence that this is, in fact, the Tryall, such as the makeup of the ballast stones. The most recent expedition took place in 2021, where they confirmed that there were no other wrecks in the area. Since we know that the Tryall wrecked there, and there is only one wreck, it must be the Tryall. After centuries of doubt, we finally have certainty.

The Western Australia Museum recently completed the restoration of one of Tryall's cannons, which is now on display in the museum.

Like the inverse of the mythical butterfly flapping its wings in China, an ice core extracted from Greenland can reveal the rise and fall of societies in European antiquity. A new study took ice cores from the Greenlandic ice sheet and used them to measure the output of lead pollution in Europe. The varying levels of lead pollution corresponded with technological and societal changes.

A global record

Ice sheets are laid down over time in layers of compacted snow. A bit like tree rings, the conditions during their formation are preserved in the layer.

By taking an ice core, scientists are effectively looking at a timeline of climate conditions over thousands of years. Air temperature, greenhouse gases, pollen levels, and chemical concentrations are printed in the layers.

This latest research is a collaborative effort between several universities and climate research organizations. The ice cores in question come from the North Greenland Ice Core Project, or NorthGRIP. NorthGRIP drilled from surface to bedrock in northern Greenland. While NorthGRIP finished drilling in 2004, the wealth of data it offers is still largely unexplored. Led by Joseph R. McConnell of the Desert Research Institute, researchers recently turned to lead levels.

When we imagine ancient coins, many of us imagine gold, but silver was far more common in most premodern coinage systems. Premodern silver smelting produced a lot of lead pollution, and archaeologists can measure ancient economic productivity through lead levels -- more lead, more coins, more activity.

What your lead poisoning says about you

Wind blows European lead emissions to Greenland, where they freeze in ice. Previous studies worked from limited samples; by using the NorthGRIP ice cores, researchers were finally able to construct a complete record of classical emissions.

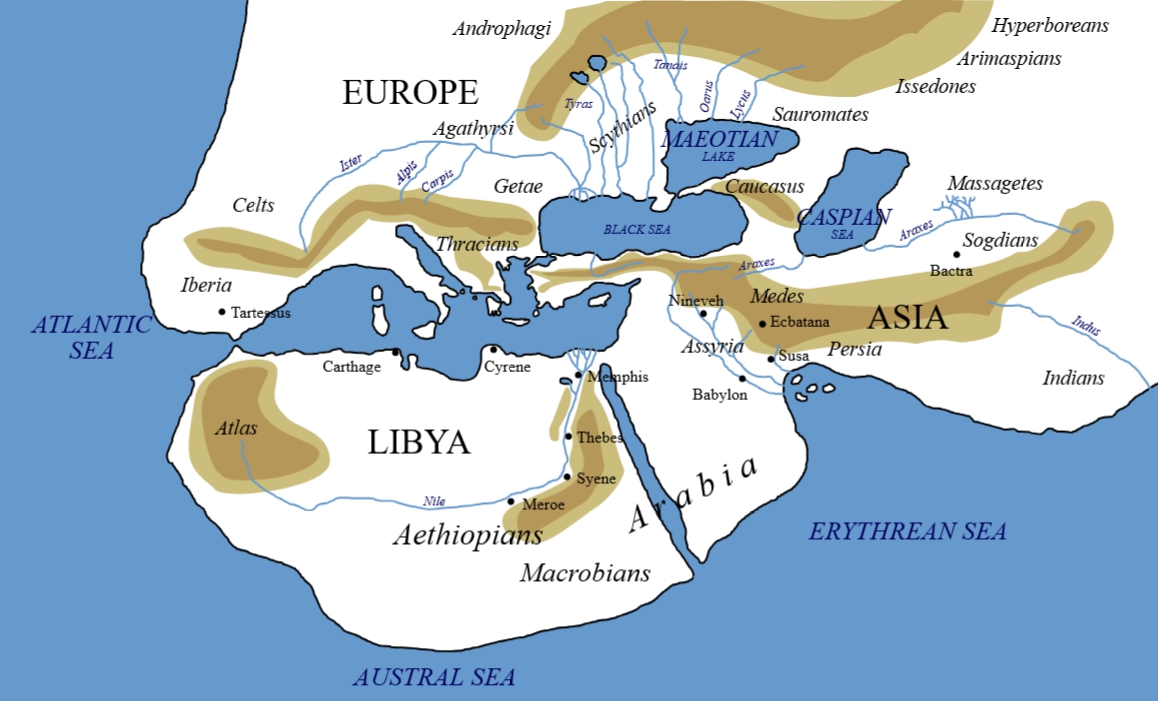

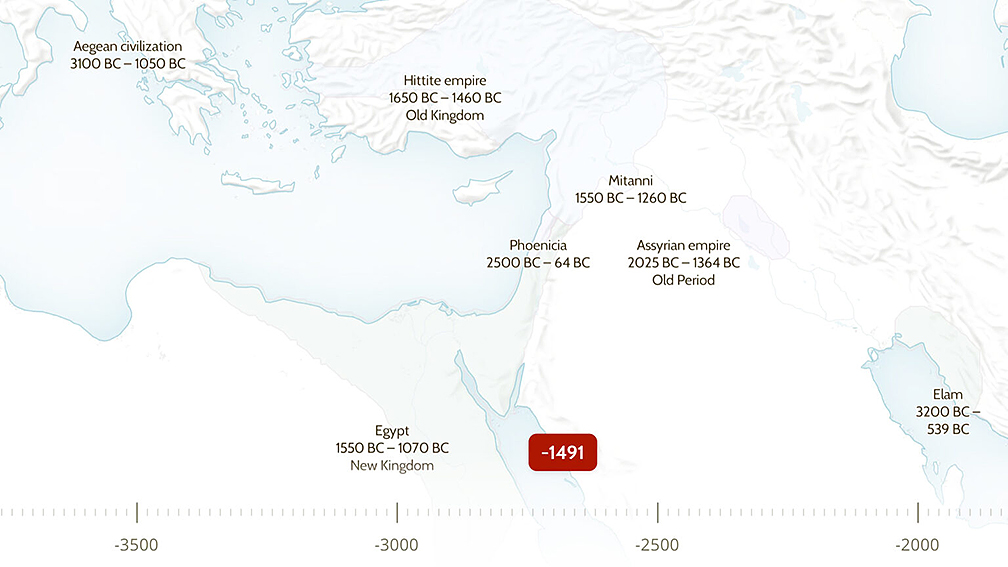

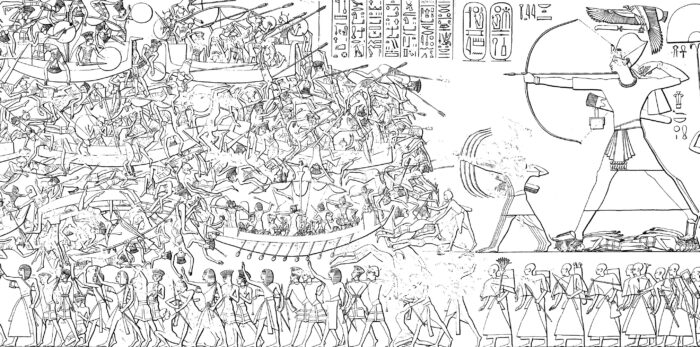

The first jump in lead levels came around 1000 BCE, when the Phoenicians began expanding into the Mediterranean. Emissions continued through the founding of the Roman kingdom and then the Republic. Levels spiked again when both the Romans and Carthaginians colonized Spain and began mining silver intensively there.

Both Punic Wars saw short-term declines, as the campaigning in Spain pulled workers away from the mines and to the battlefields. They bounced back quickly as Rome took Spain and began minting Roman silver coins in Carthaginian mines.

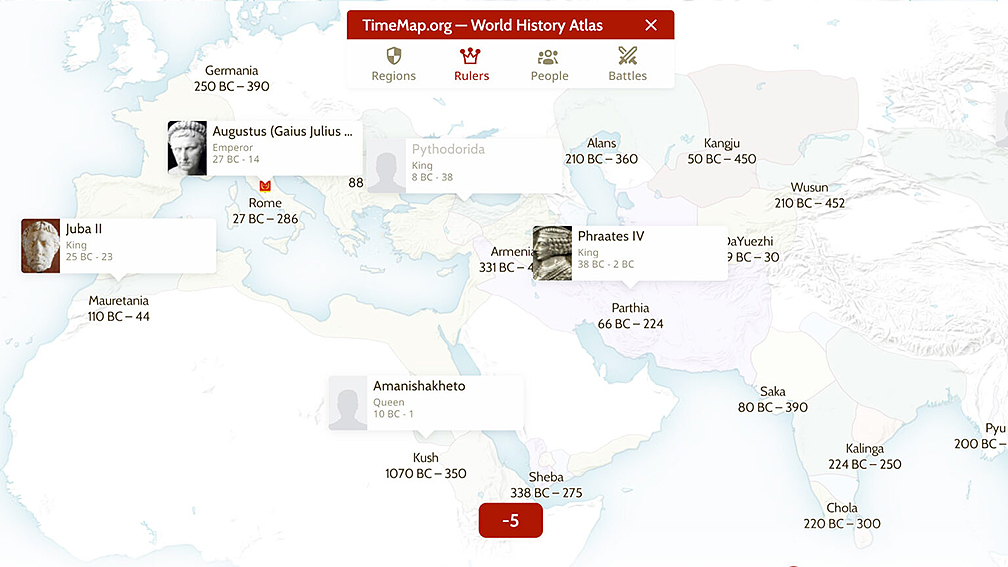

Researchers can chart the whole of Roman history in this way. Wars and political crises lead to dips, and with new conquered territory, mining ramped back up. The peak was the Pax Romana, following the ascendance of Augustus née Octavian.

Putting Edward Gibbon out of a job, the ice cores also document the decline and fall of the empire. "The great Antonine Plague struck the Roman Empire in 165 AD and lasted at least 15 years. The high lead emissions of the Pax Romana ended exactly at that time and didn’t recover until the early Middle Ages, more than 500 years later," explained coauthor Andrew Wilson, of Oxford.

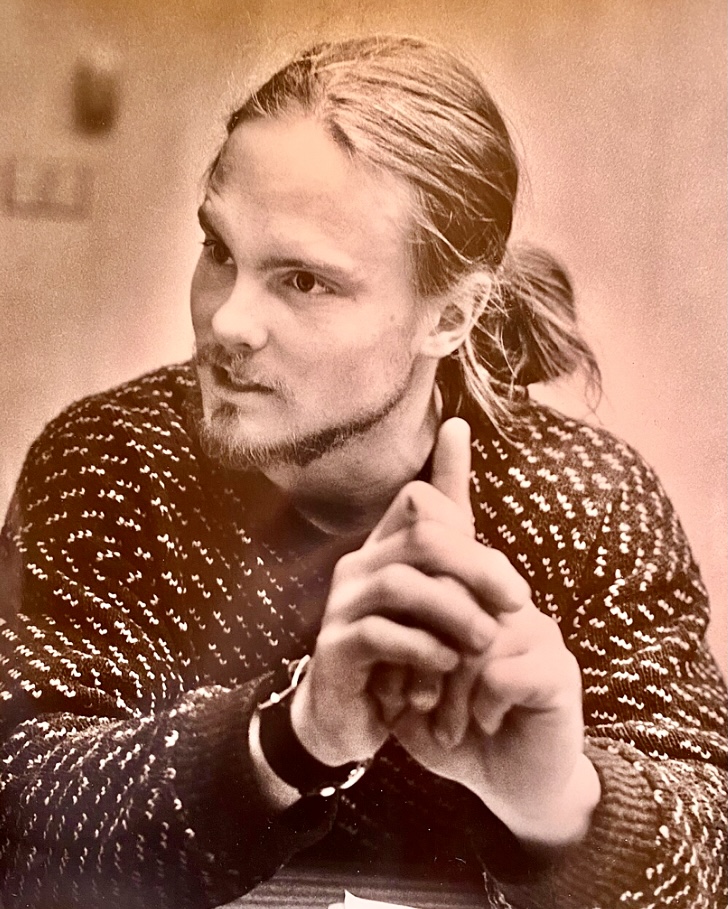

Kim Chang-ho was a South Korean mountaineer who summited the 14x8,000'ers without supplemental oxygen in record time. He pioneered numerous new routes and first ascents on 6,000m and 7,000m peaks. Today, we revisit his most notable climbs.

Early years

Most sources list Kim's birthday as September 15, 1969, but mountaineering historian Bob A. Schelfhout Aubertijn confirmed that Kim was born on July 13, with confusion arising from the Korean age system.

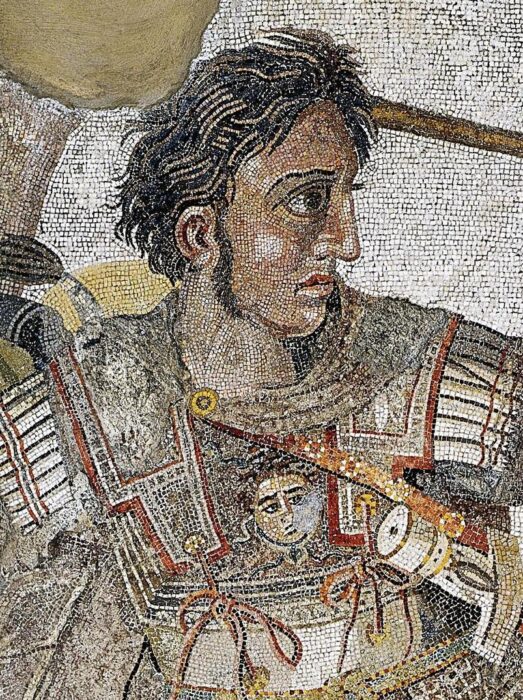

In 1988, Kim began studying International Trade at the University of Seoul. Inspired by Alexander the Great's exploits, Kim started climbing with the university’s Alpine Club.

His frequent expeditions delayed his academic progress, and he didn’t earn his Business Administration degree until 2013. Kim viewed his humanities studies as a way to enrich his climbing. He believed that understanding culture and history deepened his connection to the mountains.

By the 1990s, he was already tackling rock-climbing routes up to 5.12. Early expeditions to the Karakoram, including attempts on 6,286m Great Trango in 1993, and 7,925m Gasherbrum IV in 1996, revealed his bold -- sometimes reckless -- ambition. On Gasherbrum IV, he reached 7,450m but faced a sheer rock face without protection, instructing his partner to release the rope if he fell.

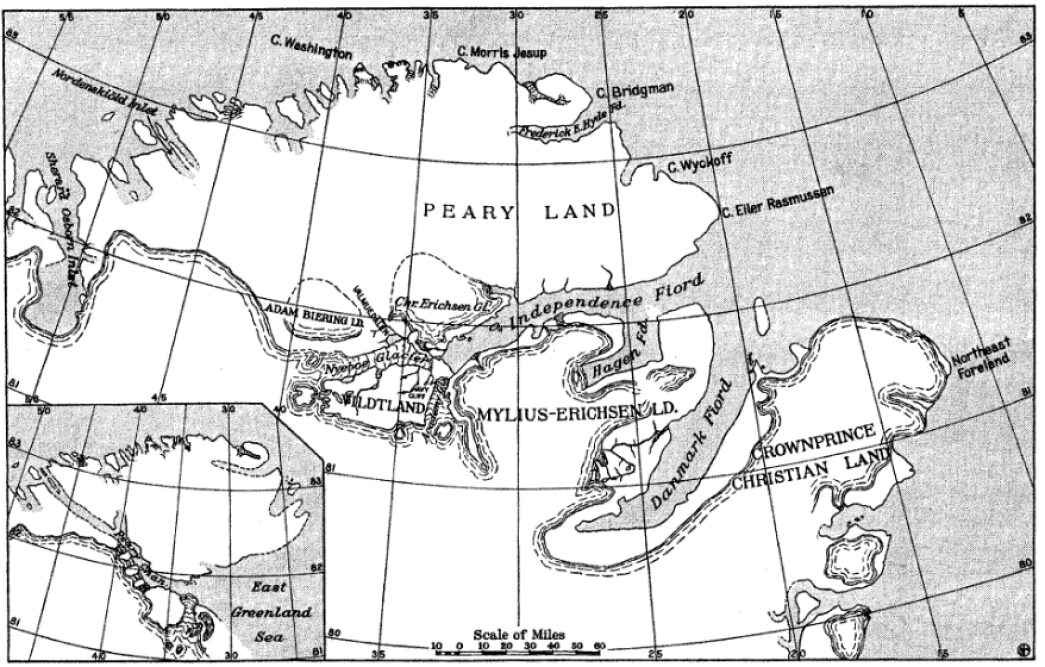

Exploration of northern Pakistan

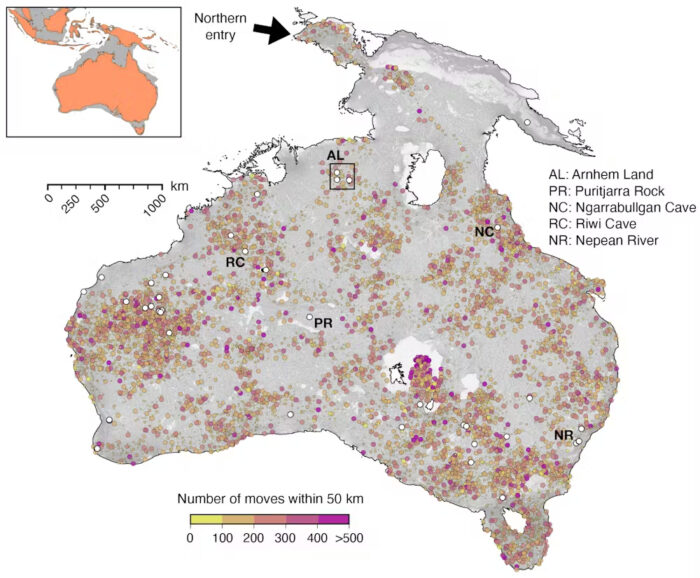

Between 2000 and 2004, Kim embarked on solo trips in northern Pakistan’s Karakoram, Hindu Kush, and Pamir ranges, prioritizing discovery over summits. As detailed in the 2023 American Alpine Journal, he surveyed glacial valleys, documented hundreds of unclimbed peaks, and built relationships with local farmers and herders. These solitary treks were driven by a desire to understand the geography, culture, and history of the regions.

Kim’s journals reveal a meticulous approach, with photographs and descriptions of potential routes forming a database that remains a valuable resource for climbers. His interactions with locals shaped his climbing decisions, ensuring cultural sensitivity in his choice of peaks. This period of exploration laid the groundwork for his later ascents, blending adventure with respect for the human and natural contexts of the mountains.

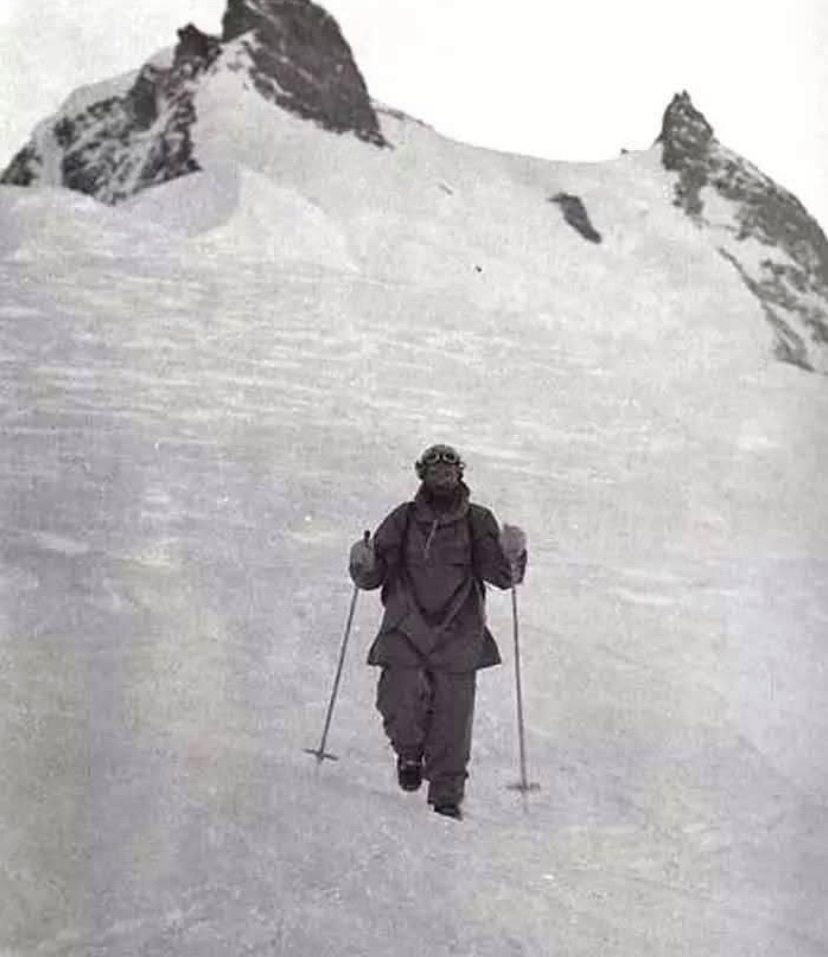

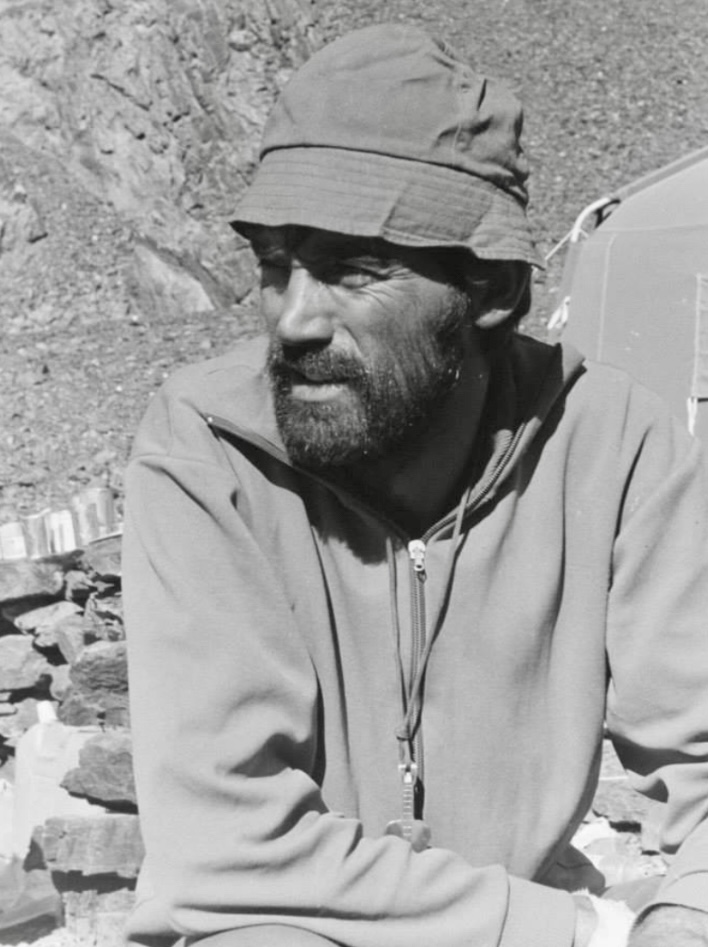

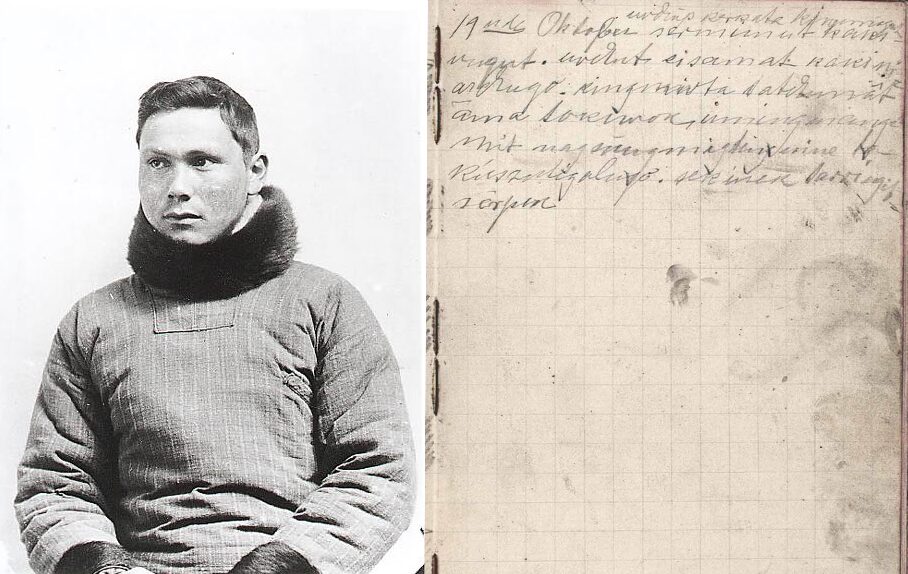

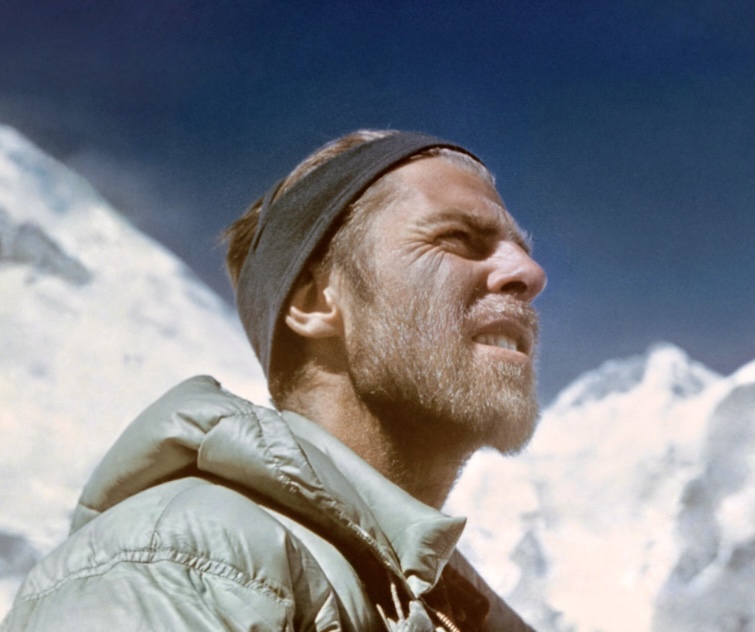

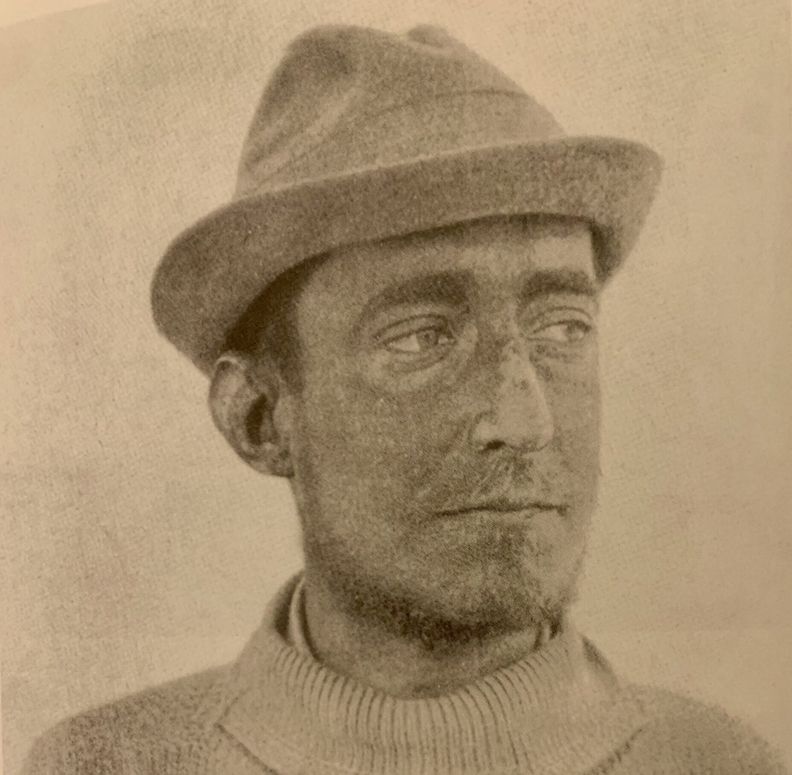

Photo: Kim Chang-ho

Four first ascents of 6,000m peaks

Kim’s explorations in Pakistan led to a series of remarkable solo first ascents in 2003, when he was 33. The American Alpine Journal documents four solo climbs of 6,000m peaks in the Hindu Raj and Karakoram ranges.

He carried out the first ascent of 6,105mm Haiz Kor in the Thui Range of the Hindu Raj, by a challenging route via the southeast face and south ridge through a complex icefall.

Kim also made first ascents of 6,225m Dehli Sang-i-Sar in the Little Pamir, 6,189m Atar Kor in the Hindu Raj, and 6,200m Bakma Brakk in the Masherbrums.

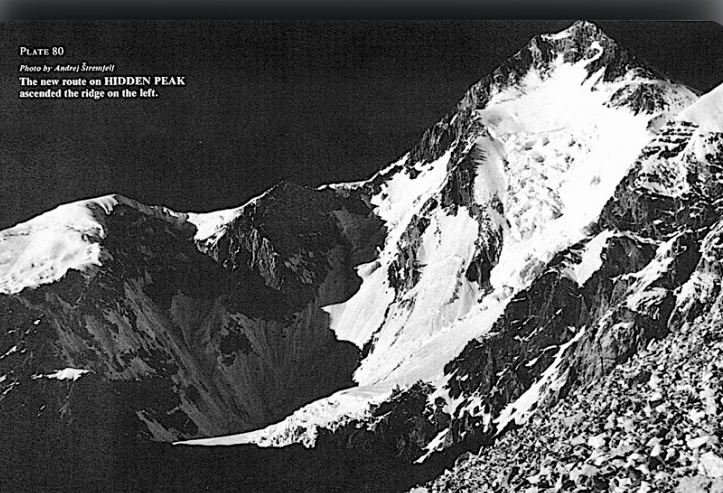

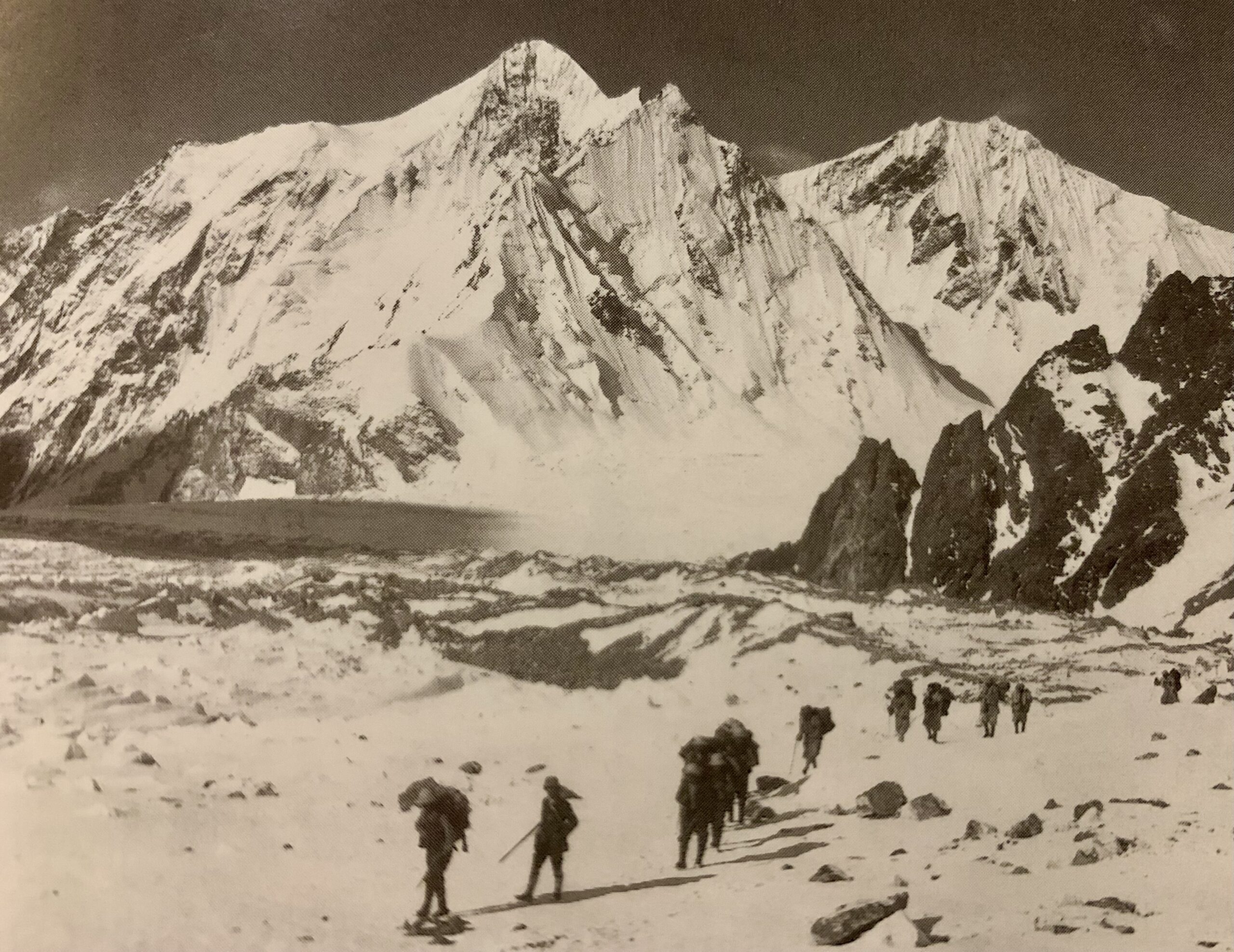

Dehli Sang-i Sar from the southwest, showing the general line of Kim Chang-ho's solo ascent along the upper east ridge in 2003. Photo: Kim Chang-ho

Mastering 7,000’ers

In 2008, he led the first ascent of 7,762m Batura II, though the expedition’s use of fixed ropes drew criticism, prompting him to refine his lightweight approach.

In 2012, Kim and An Chi-young made the first ascent of 7,092m Himjung in Nepal, climbing via its southwest face. The expedition earned them the Piolet d’Or Asia Award.

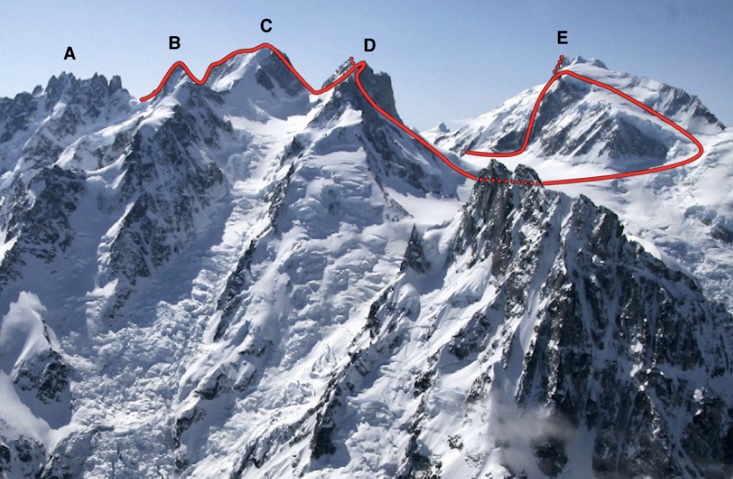

In 2016, Kim and two partners opened a new 3,800m alpine route on the south face of 7,455m Gangapurna in Nepal. Described by the 2017 Piolet d’Or committee as "bold and lightweight," it earned an Honorable Mention, marking a historic recognition for Korean climbers.

During the Gangapurna expedition, Kim and his partners also attempted the south face of unclimbed Gangapurna West, where they reached the summit ridge.

One year after Gangapurna, the tireless Kim led an expedition to Himachal Pradesh in India, aimed at fostering a younger generation of Korean climbers and developing their skills and experience. The team made the second ascent of 6,446m Dharamsura, and climbed 6,451m Papsura via a direct route on the south face.

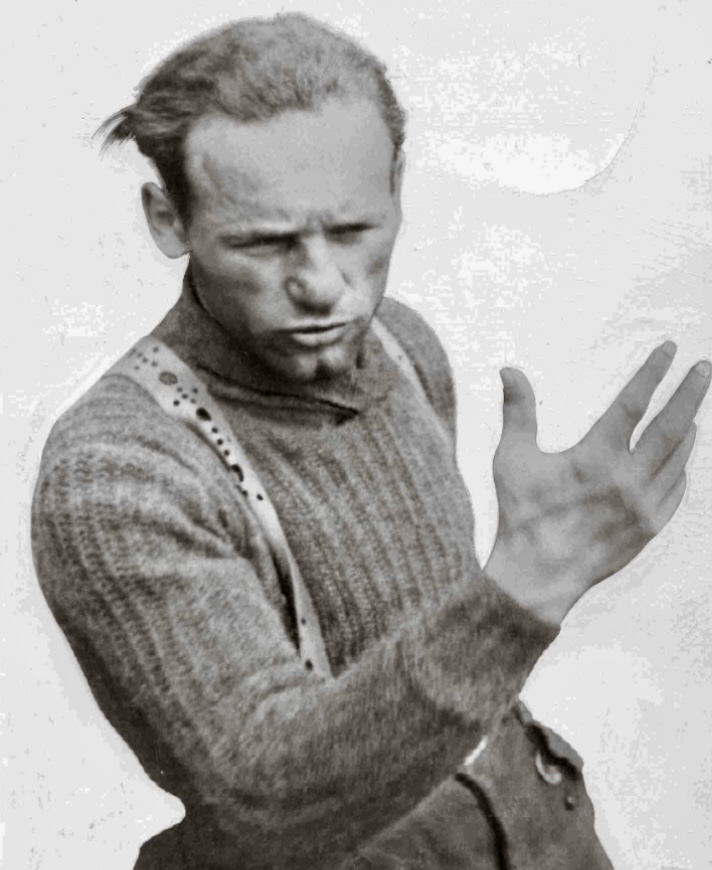

Choi Seok-mun and Park Joung-yong, climbing partners of Kim Chang-ho, approach the summit of Gangapurna. Photo: Korean Way Project

Summiting 8,000'ers

Kim summited all 14 of the world’s 8,000m peaks without supplemental oxygen, in record time.

Starting in 2006 with the Busan Alpine Federation’s Dynamic Hope Expedition (led by Hong Bo-Sung), Kim and a small team relied on minimal support, avoiding Sherpas and oxygen. Kim studied geography and history to learn more about his routes.

Kim completed the 14x8,000'ers in 7 years, 10 months, and 6 days, setting a record for the fastest completion without oxygen at the time. He surpassed Jerzy Kukuczka's record by one month.

Kim didn't set out with the explicit goal of climbing the 8,000'ers so quickly. His pursuit was primarily driven by his passion for mountaineering and a desire to climb these peaks in a pure, lightweight style.

Kim ascended three 8,000m peaks twice: Nanga Parbat, Gasherbrum I, and Gasherbrum II.

Among his 8,000m climbs, his south-north traverse of Nanga Parbat in 2005 and his sea-to-summit ascent of Everest in 2013 deserve special mention.

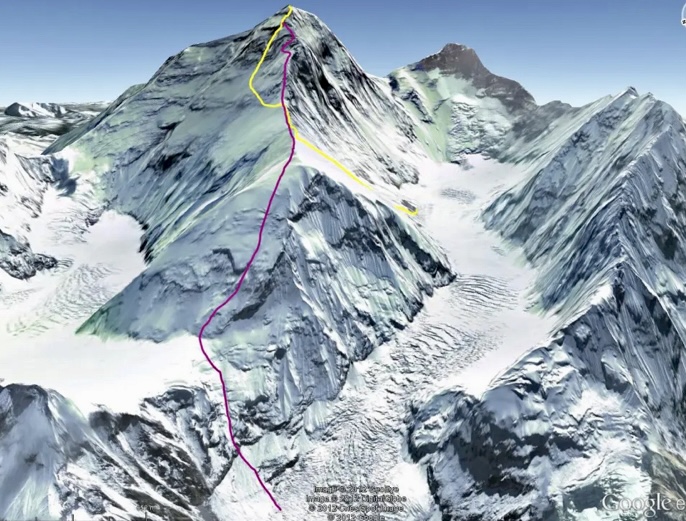

The south face of Gangapurna, showing (in red) the Canadian Route (1981), and (yellow) the Korean Way (2016). Photo: Korean Way Project

Nanga Parbat, 2005

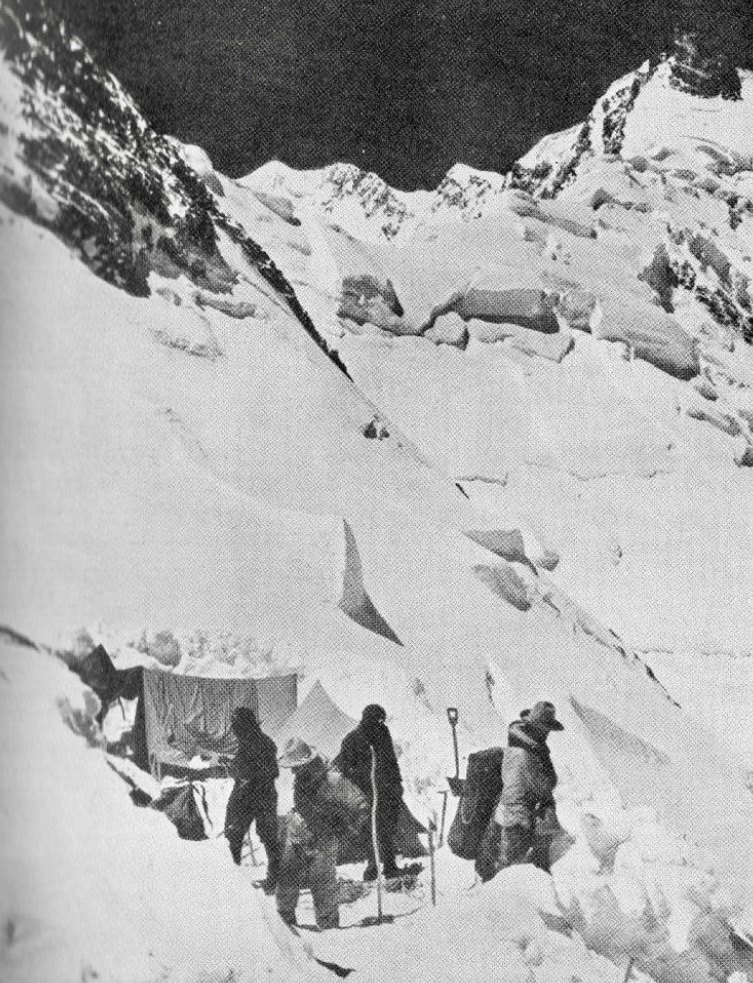

In 2005, Kim climbed Nanga Parbat’s massive Rupal Face. The Korean Nanga Parbat Rupal Expedition lasted 109 days. They arrived at Base Camp on April 20 after a heavy snowstorm. Over the next 12 days, the team set up Camp 1 at 5,280m and Camp 2 at 6,090m, following a line close to the 1970 Messner Route.

The weather was brutal, with snow falling daily in May, destroying seven tents and burying Camp 2 under fresh snow. Despite these setbacks, by June 14, after 43 days of effort, the team established Camp 3 at 6,850m. Near the end of June, the team prepared for a summit attempt, and on June 26, Kim and three other climbers started their push. However, at 7,550m on the Merkl Icefield, a rock hit team member Kim Mi-gon in the leg, forcing the group to abort.

Undeterred, Kim and climbing partner Lee Hyun-jo made another attempt on July 13, starting from Camp 4 at 7,125m. They faced constant danger, dodging falling rocks and ice. After a 24-hour climb, they reached the summit of Nanga Parbat.

Kim Chang-ho. Photo: Abbas Ali

A difficult descent

Kim and Lee chose to go down the Diamir Face via the Kinshofer Route, unroped, to save time. In the middle of the descent, they triggered a wind slab avalanche. Lee was buried, and Kim was swept 50m downhill, scraping his face and losing his headlamp. Both managed to free themselves and continued down, exhausted and hallucinating, believing another climber was ahead of them. They reached another expedition’s tents at 7,100m but decided against stopping, fearing they might not wake up if they rested. After an incredible 68 hours from Camp 4, they arrived at the Diamir Base Camp, impressing others with their speed and resilience. Lee appeared remarkably fresh despite the ordeal.

This expedition was a turning point for Kim. The climb was a tactical, siege-style effort, relying on fixed ropes and a larger team, very different from the lightweight, alpine-style climbs he later became known for. During the descent, Lee’s emotional radio call to a teammate at Base Camp, expressing regret that they weren’t together, deeply affected Kim.

Kim reflected on his selfishness, realizing that reaching the summit meant little without returning safely with his team. This experience shaped his philosophy moving forward, which would emphasize teamwork, respect for the mountains, and survival over personal glory.

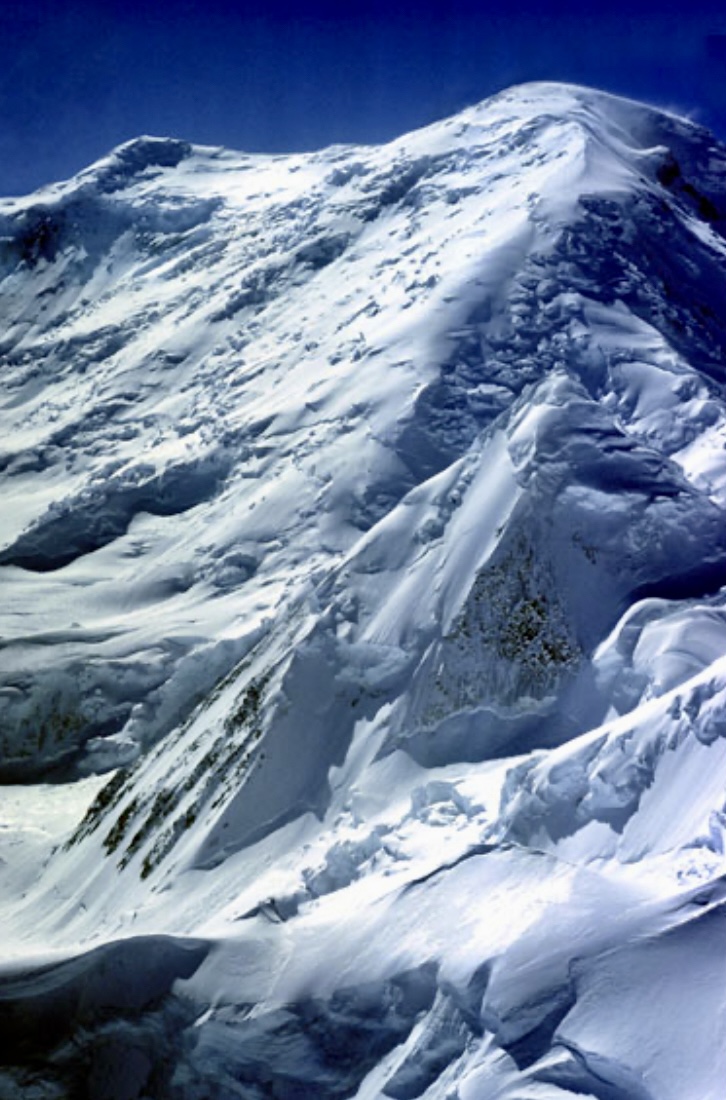

Views of Everest from neighboring Lhotse. Photo: Kadyr Saydilkan

Everest, 2013: Starting from sea level

Kim’s 2013 Everest ascent was the final step in his quest to climb the 8,000m peaks without supplemental oxygen, making him the first Korean to do so. But his Everest climb was not just about reaching the top; it was a unique adventure.

Kim’s journey to Everest’s summit began far from the mountain itself. He wanted to make the climb special by starting at sea level and traveling to Base Camp without using motorized transport.

On March 20, 2013, he began his expedition from Sagar Island near Kolkata, India. From there, he kayaked 156km on the River Ganges, cycled 893km through northern India to Tumlingtar in Nepal, and then trekked 162km to Everest Base Camp. This sea-to-summit approach was rare and challenging, inspired by earlier climbers like Tim Macartney-Snape and Goran Kropp, but Kim added a twist by kayaking part of the way.

Once at Everest Base Camp, Kim prepared to climb the mountain via the standard Southeast Ridge route from the Nepal side without oxygen. He moved steadily up the mountain, navigating the Khumbu Icefall, the Western Cwm, and the steep slopes leading to the South Col. On May 20, Kim reached the summit.

Sadly, Kim’s climbing partner, Seo Sung-ho, died during the descent. This loss cast a shadow over the triumph, but Kim’s accomplishment remained a mountaineering landmark.

Kim Chang-ho and his team near the Sara Umga La at 5,020m, west of Dharamsura and Pasura peaks, in 2017. Photo: Korean Way Project

Mountaineering philosophy

Kim’s mountaineering philosophy viewed climbing as a means of learning and coexistence, not conquest. He avoided treating peaks as mere challenges, instead choosing routes with historical or cultural significance. After losing his partner Seo Sung-ho on Everest in 2013, Kim founded the Korean Himalayan Fund to support young climbers in creative ascents. His database, preserved by his wife Kim Youn-kyoung, includes detailed notes on geography and local names.

Kim’s death

Kim’s life ended on October 11, 2018, when an avalanche, possibly triggered by a serac collapse, destroyed his team’s Base Camp beneath 7,193m Gurja Himal, located south of Dhaulagiri VI, in Nepal. The Korean Way Project expedition, aiming for a new route on the south face, included five South Korean climbers and four Nepali guides, all of whom perished.

Kim’s journal, ending on October 10, suggests the tragedy struck overnight. By the time of his death, he was recognized as South Korea’s most accomplished climber. Kim was 49 years old.

His legacy endures through his database, the Korean Himalayan Fund, climbers like Oh Young-hoon who carry forward his vision, Kim’s daughter (Danah, born in 2016), his wife, and through the international mountaineering community, who preserve his memory.

Kim Chang-ho. Photo: En.namu.wiki

On July 11, 1985, Pierre Gevaux made the first paragliding descent from the summit of an 8,000m peak, soaring down from 8,034m Gasherbrum II. This groundbreaking feat opened a new chapter in mountaineering history.

Gevaux was part of a French expedition to Pakistan led by Claude Jaccoux. It included clients, three guides, and two high-altitude porters. They shared Base Camp with another French team led by well-known mountaineer and extreme adventurer Jean-Marc Boivin.

The expedition began in early July, with climbers establishing camps along the standard route. On July 11, Gevaux and the other team members topped out. The summit day featured clear weather, offering a rare window for his paragliding descent.

Paragliding technology was in its infancy, and Gevaux’s paraglider was likely a basic or parachute-like canopy. It required significant skill to control, especially in the thin air and unpredictable winds at such an extreme altitude.

According to Xavier Murillo, Gevaux's first two attempts to fly from the summit failed. Each time he had to climb back up, catch his breath, gather his thoughts, and tell himself that he would be able to do it. The third time was the charm.

The descent covered a vertical drop of several thousand meters to Camp 1 at 6,000m. He reached it in 5 minutes and 45 seconds. It had taken him five months of preparation, two months on the expedition, and four days of climbing.

Gevaux’s feat impressed other mountaineers who were on Gasherbrum II that day, including Jean-Marc Boivin.

Boivin paraglides down Everest

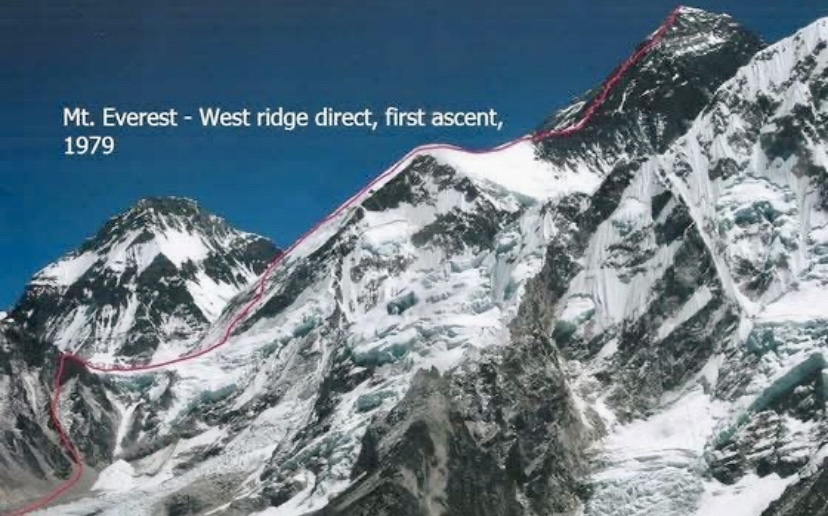

Boivin was an adventurer known for his first ascents, ski descents, and pioneering hang gliding and paragliding. He was reportedly inspired by Gevaux’s paragliding descent from Gasherbrum II. On that expedition, Boivin broke a hang glider altitude record when he successfully launched from the summit. Previously, in 1979, Boivin had set a hang glider altitude record when he flew from nearly 8,000m after climbing K2.

Three years after Gevaux’s flight, on Sept. 26, 1988, Boivin achieved the first paragliding descent from just below the summit of Everest. The thin air at 8,848m made launching difficult, and gusty winds required precise timing to ensure a safe takeoff. Boivin’s success cemented his reputation as a pioneer of extreme sports, though he tragically died two years later while BASE jumping off Angel Falls in Venezuela.

You can read more about Everest’s paragliding and hang gliding history here.

Paragliding descents from other 8,000’ers

Gevaux’s 1985 flight and Boivin’s 1988 flight pointed the way for others.

In 1994, Australian Ken Hutt paraglided down from 7,200m on Cho Oyu.

In July 2019, Austrian climber Max Berger paraglided from the shoulder of 8,051m Broad Peak, landing in Base Camp 17 minutes later. Though not from the summit, this descent was a significant high-altitude feat.

On July 19, 2022, French climber Benjamin Vedrines paraglided from Broad Peak’s summit ridge after a speed ascent without supplemental oxygen, landing at Base Camp in about an hour.

On July 28, 2024, French climbers Benjamin Vedrines, Jean-Yves Fredriksen, Zeb Roche, and Liv Sansoz paraglided from the summit of K2 despite a Pakistani paragliding ban. All four had summited without bottled oxygen.

Vedrines -- after claiming a climbing speed record of 10 hours, 59 minutes, and 59 seconds -- launched first, landing at Base Camp in 30 minutes. Fredriksen landed at 6,600m after struggling for 90 minutes to take off, and Roche and Sansoz achieved the first tandem paragliding descent from an 8,000m summit.

Most recently, on June 24 of this year, David Goettler paraglided from 7,700m after summiting Nanga Parbat via the Schell Route on the Rupal Face without bottled oxygen.

In the video below, you can watch Gevaux's pioneering paragliding descent from Gasherbrum II in 1985:

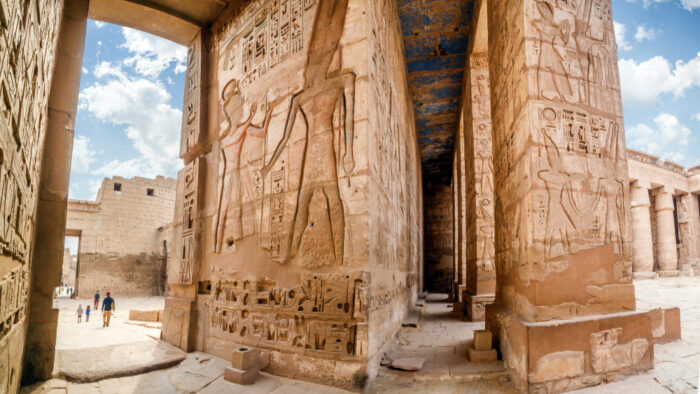

While Egyptian kings and queens are the most famous examples of mummification, the practice wasn’t just for pharaohs. It expanded over time until everyone from the poor up were being preserved for eternity.

So, where are all the mummies? Well, unfortunately, 700 years of rich Europeans ate them. For their health, of course.

From a 12th-century translation error, a massive trade kicked off, depopulating the tombs of Egypt to populate European apothecaries -– and starting an underground market in fake mummy powder.

Bitumen and mūmiyah

Why did Europeans think that eating mummies was a good idea? It's all to do with bitumen. Bitumen is a viscous petroleum product, which occurs naturally in a semi-solid form. Bitumen is particularly common around the Dead Sea, and is useful for waterproofing and as a glue. Archaeological evidence shows that both early humans and their Neanderthal cousins used bitumen tens of thousands of years ago. It even appears in the Bible as the mortar which was used in the tower of Babel.

By the classical era, bitumen was used in everything from shipbuilding to jewelry. People also started using it as medicine. Pliny the Elder, a Roman author and naturalist, lists 27 discrete medicinal applications for it. These include staunching blood flow, diagnosing epilepsy, treating leprosy, dysentery, and gout, and curing toothache.

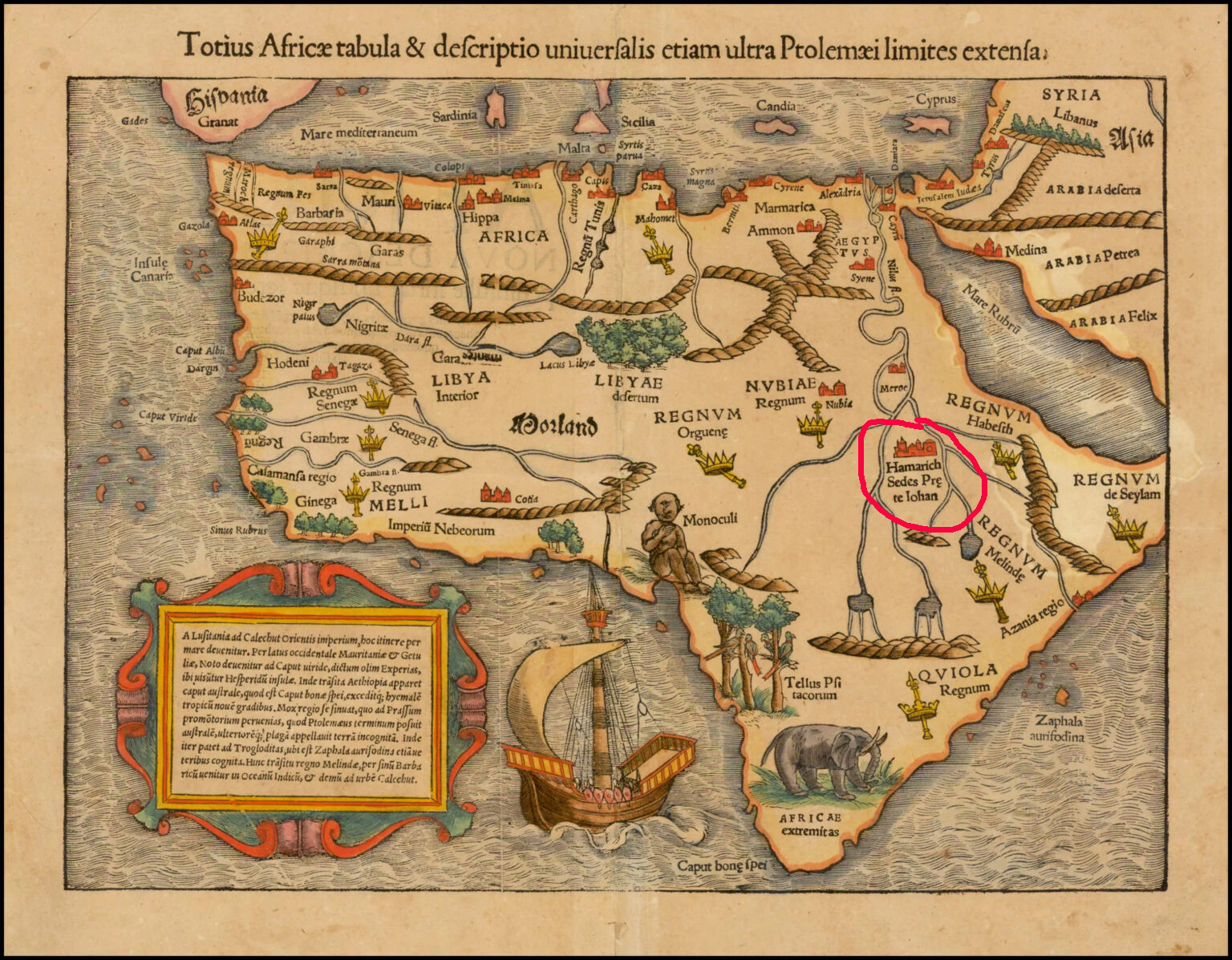

After the fall of the Roman Empire, Muslim scholars took pains to preserve classical learning. By the Middle Ages, Arabic authors were considered the foremost medicinal experts throughout Europe and the Middle East. The tradition of using bitumen as medicine continued through the works of scholars like Avicenna, who prescribed it for concussions, paralysis, and more. He didn't call it "bitumen," though. He called it mūmiyah, from the Persian word mum, meaning wax.

A medieval game of telephone

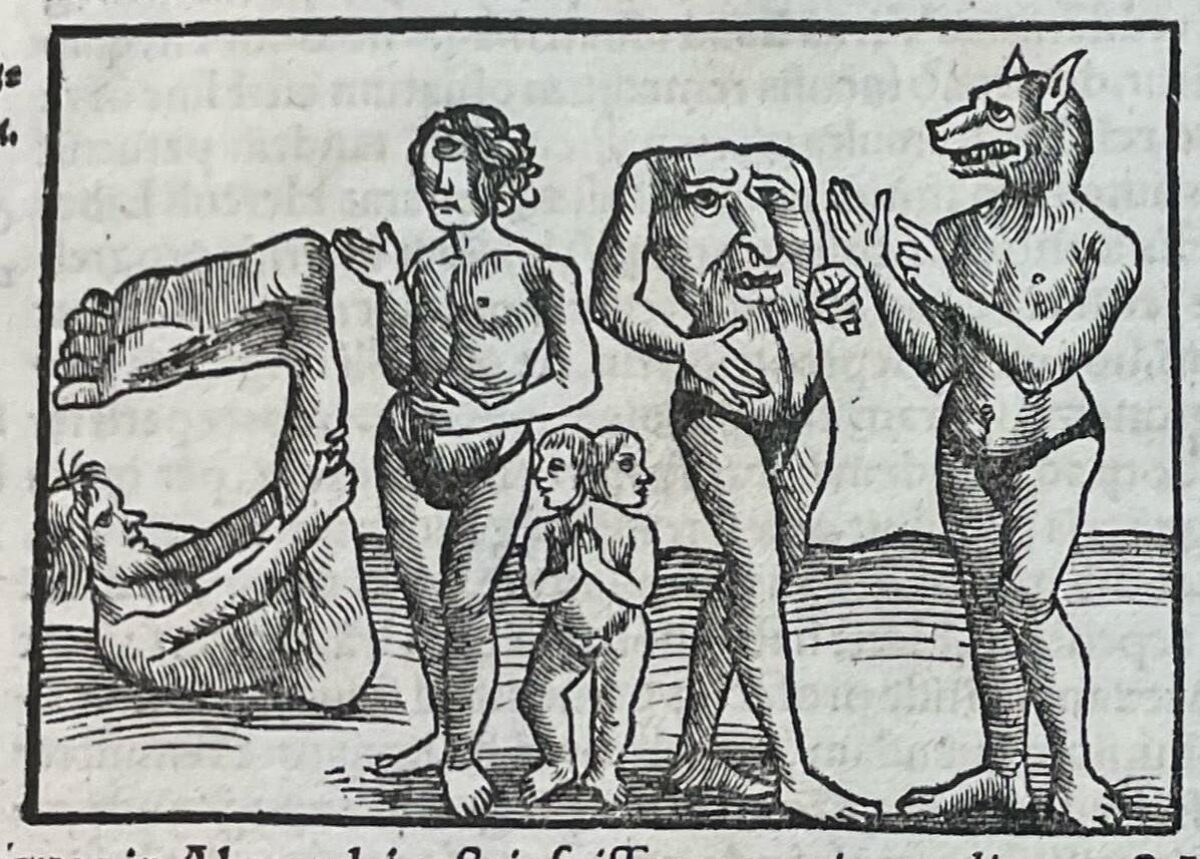

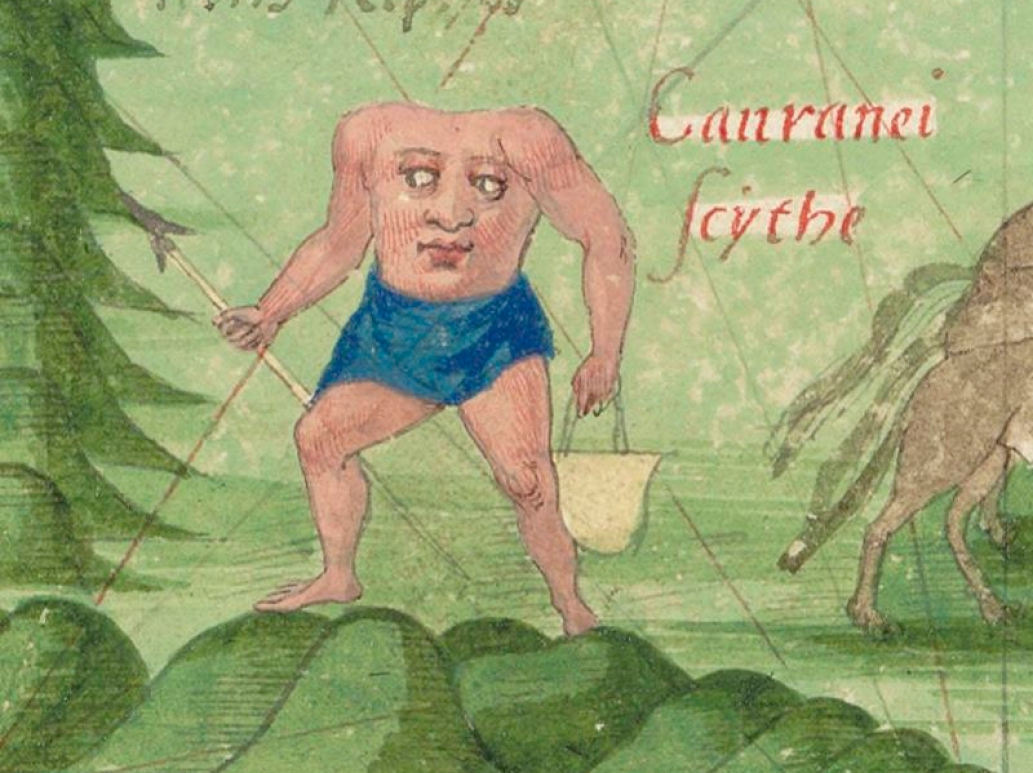

The Ancient Egyptians didn't use bitumen for their mummies. However, the dark resin they used resembled bitumen, leading many classical and medieval observers to believe that bitumen coated Egyptian mummies. So the same word came to refer both to naturally occurring bitumen and the dark waxy coating found on Egyptian mummies.

In the 12th century, an Italian translator of Arabic texts named Gerard of Cremona came across Rhazes of Baghdad's reference to mūmiyah. Gerard said the product was created when "the liquid of the dead, mixed with the aloes, is transformed and is similar to marine pitch.”

Another European, Simon Geneunsis, translated a work by Arab physician Serapion the Younger that referenced medicinal bitumen as "mumia." Geneunsis interprets the word along the same lines as Gerard of Cremona, calling it "the mumia of the sepulchers," which is formed when the aloes and spices used to prepare the dead mix with the liquids the corpse itself expels."

Meanwhile, crusaders were bringing back the bitumen medicine fad from the Islamic medical traditions of the Middle East. Unfortunately, the easily accessible supplies of bitumen in the area were limited. Shrewd Alexandrian merchants realized that there was all this mumia lying around, coating the bodies of the dead. They began raiding tombs, breaking the resinous bodies up, and exporting them to Europe.

The fact that the mumia came from corpses didn't bother people much, possibly due to the confusion between medical mumia and Egyptian mummies. Before long, mumia stopped being the substance on the mummy and became the mummy itself.

It's good for what ails you

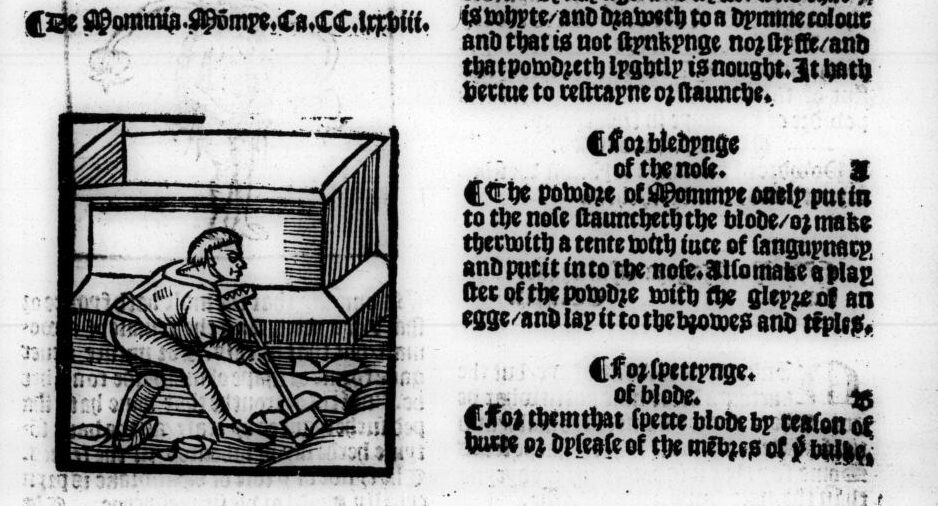

Mumia became a wildly popular remedy in Europe, sold in every well-stocked apothecary. One influential pharmacopeia, Theatrum Botanicum, contains a long list of conditions mumia is useful for, including headaches, colds, coughs, seizures, heart problems, poisoning, scorpion stings, snake bites, bladder ulcers, paralysis, and retention of urine. Treatments involved combining mumia with other ingredients, usually a liquid like wine or goat milk.

Genoese physician Giovanni da Vigo considered mumia an essential medicine for ship's physicians and village doctors. He claimed it promoted wound healing and staunched bleeding. Sir Francis Bacon, the eminent English philosopher, and the physicist Robert Boyle, both considered it useful for wounds, falls, and bruises.

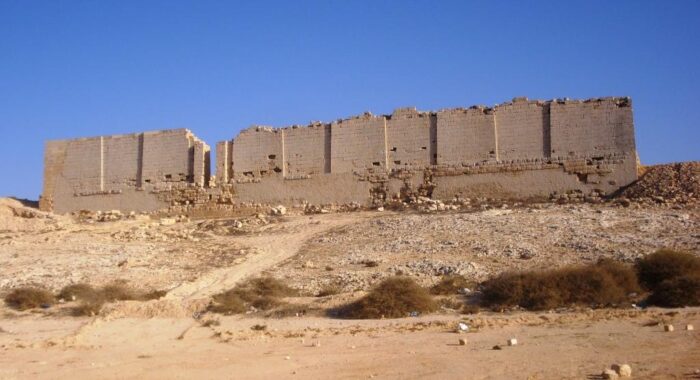

The French king, Francis I, was a habitual mummy consumer; contemporaries reported that he always carried a mixture of rhubarb and mumia on his person, just in case. Nicasius Le Febre, chemist to England's King Charles II, recommended mummy from Libya specifically.

By the way, if you were wondering how it tasted, the English College of Physicians has the answer. Mummy was listed in their official pharmacopeia from 1618 to 1747, where it is described as being "somewhat acrid and bitterish."

Supply chain issues

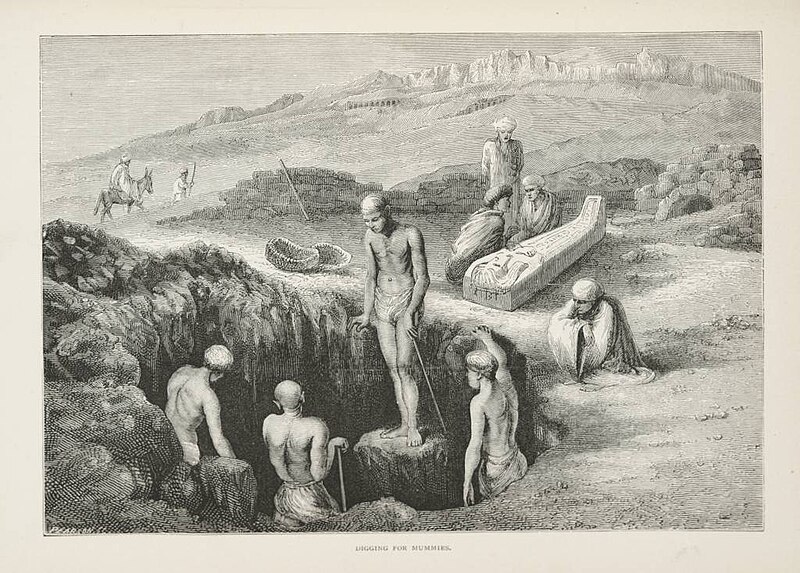

Egyptian authorities were not actually keen on all the grave robbing and corpse exporting that was happening. In 1428, authorities in Cairo captured and tortured several people connected to a mummy scheme. They confessed to robbing tombs, boiling the mummified bodies in a pot, and selling the oil which rose to the surface.

It was illegal to export Egyptian mummies out of Egypt. But enforcement could be lax, especially if you had money to grease the wheels. Englishman John Sanderson visited Egypt in 1586, where he explored a sepulcher and broke off chunks of blackened mummified flesh. He applied the correct bribes and compliments, and sailed off with 600 pounds worth of "divers heads, hands, arms, and feete."

For every literal boatload of real pillaged mummies, there was at least an equal measure of mummies created specifically for export. Many mummy sellers in Egypt found it was easier to source fresh corpses and dry them than it was to dig up old ones. These fresh corpses mostly came from executed criminals, plague victims, and enslaved people.

The Italian traveler Ludovico di Varthema wrote about the local production of mumia during a visit to the Arabian Peninsula. According to him, there were two kinds; the first was made from the dried-up remains of people who had died recently while crossing the desert. The other, nobler and more pure kind, was "the dryed and embalmed bodies of kynges and princes."

In truth, even authentic mumia wasn't made from rulers, but from their subjects. European nobles liked to imagine their healthful powder came from ancient priestesses and kings, but the remains of the poor were far more plentiful and accessible.

Paracelsus and domestic mummy manufacture

Though a fair amount of the mummy product on the market was inauthentic, the real stuff was still being sold into the modern era. One recent study analyzed the contents of an 18th-century pharmaceutical jar labelled "mumia." They found that the contents really were the remains of an Egyptian mummy from the Ptolemaic period.

But without our modern analysis tools, the question of mumia authenticity was an ongoing problem for physicians. As the supply became more questionable, some medical authorities began to wonder whether mumia being "authentically Egyptian" was even important.

Some definitions of mumia dropped the ancient Egyptian element entirely, ascribing benefits to any old preserved human flesh. The influential physician Paracelsus, who spawned a legion of followers, believed the medicinal benefit of mumia came from a transfer of life energy. To make his mumia, he left a fresh body out exposed. The best bodies were of young, healthy men who died suddenly. Other recipes in this line were even more specific, preferring a 24-year-old redheaded man who was recently executed.

There was a persistent belief that there was a vital animating force remaining in corpses, and one could benefit from this force by consuming corpse products. In the time of Paracelsus, for instance, executioners would collect and sell the blood of those they executed. People believed that drinking it promoted general health and cured epilepsy. Bandages soaked in human fat were applied to wounds, and powdered human skull was prescribed for headaches.

The broader genre of corpse medicine is beyond the scope of this article, but suffice it to say that mumia wasn't always the only human-derived medicine available.

Some reasonable concerns

Now I'm not a doctor, but I feel confident in saying that "you should eat powdered human corpses for nosebleeds" is not best practice. By the 16th century, many doctors were starting to think along the same lines.

Ambroise Pare, surgeon to four French kings, published a 1582 treatise decrying the use of mummy. He argued that most mummy sold was actually manufactured in France from the recently dead, and also didn't work. In his professional experience, it had not only failed to stop bleeding but had unsurprisingly caused the patient to have an upset stomach and bad breath.

Pare's German contemporary, Leonhart Fuchs, made similar arguments. He also laid out the series of medieval translation errors which had led to the idea of mumia. Fuchs decried the "stupid...credulity of certain doctors of our age," who still prescribed mummy.

Additionally, some commentators were beginning to recognize the historical and cultural wealth that was being ground up for tinctures. English natural philosopher Thomas Browne opined that "The Ægyptian Mummies, which Cambyses or time hath spared, avarice now consumeth. Mummy is become merchandise, Mizraim cures wounds, and Pharaoh is sold for balsams."

There was also cannibalism. Michel de Montaigne, a 16th-century French writer and early critic of colonialism, pointed out the hypocrisy of demonizing cannibalistic practices in the New World while taking medicinal human flesh at home. But most people didn't think of it as cannibalism, any more than people today would consider a blood transfusion cannibalism. Mumia wasn't food, it was medicine.

Still, as time went on, people were increasingly wondering if it was medicine they should be taking. Mumia mania peaked in the 18th century, but took much longer to fade entirely.

Consuming Egypt

For wealthy Europeans, part of the appeal of mumia was the mystical, exotic associations. For centuries, Europeans treated the bodies of deceased Egyptians with a combination of fetishistic fascination and blatant disrespect. They were curios and collectors' items, souvenirs of exciting trips turned household decor.

Mummy unwrapping parties were popular in 19th-century Europe, where middle and upper-class men and women would watch a mummy's bandages be unwound, revealing its body as the finale of the morbid show.

The remains were consumable as a variety of commercial products. A popular paint color from the mid-18th to 19th centuries was "mummy brown." This pigment was made from ground-up mummified bodies. Art historians believe this rich, warm brown pigment appears in a number of well-known paintings, including Eugene Delacroix's famous Liberty Leading the People. The last tube of mummy brown was produced, unbelievably, in 1964.

There are also accounts, of varying reliability, that both human and animal mummies were used as fertilizer, paper (from their bandages), and fuel for locomotives. These claims are likely exaggerated, but they speak to the manner in which mummified Egyptian remains were treated at the time. As Imperial plunder, they were, literally, things to be consumed.

The end of the mummy-eating era?

By the end of the Victorian period, mumia had fallen out of popular use. But it was still available for sale, and occasionally prescribed, into the beginning of the 20th century. The last known appearance of the drug for sale is in a 1908 Merck catalogue. The German pharmaceutical advertised, "Genuine Egyptian mummy as long as the supply lasts, 17 marks 50 per kilogram."

Rich old Europeans didn't actually eat up all the mummies. Archaeologists are still finding them, for one. It's impossible to say how significantly the manufacture of mumia impacted the number of surviving mummified remains. It's safe to say, though, that nearly a millennium of looting Egypt led to the loss of untold historical and cultural knowledge.

The 1908 example is troublingly recent, but we might still be tempted to dismiss mumia as something from another, less enlightened age. Exporting ground-up mummy to eat as a health supplement is something so patently absurd that a modern reader might make the mistake of smugly holding themselves above all those involved in the practice.

It's true that we don't eat mummies anymore. But physical and cultural wealth is still extracted from exploited nations for the consumption of the global north.

Most human bones available for sale in the West, as curios or medical teaching tools, come from India, though the export of human skeletons was officially banned in the 1980s. World-class museums still display cultural artifacts and remains of colonized people for the predominantly white public to gawk at. Mummy remains merchandise.

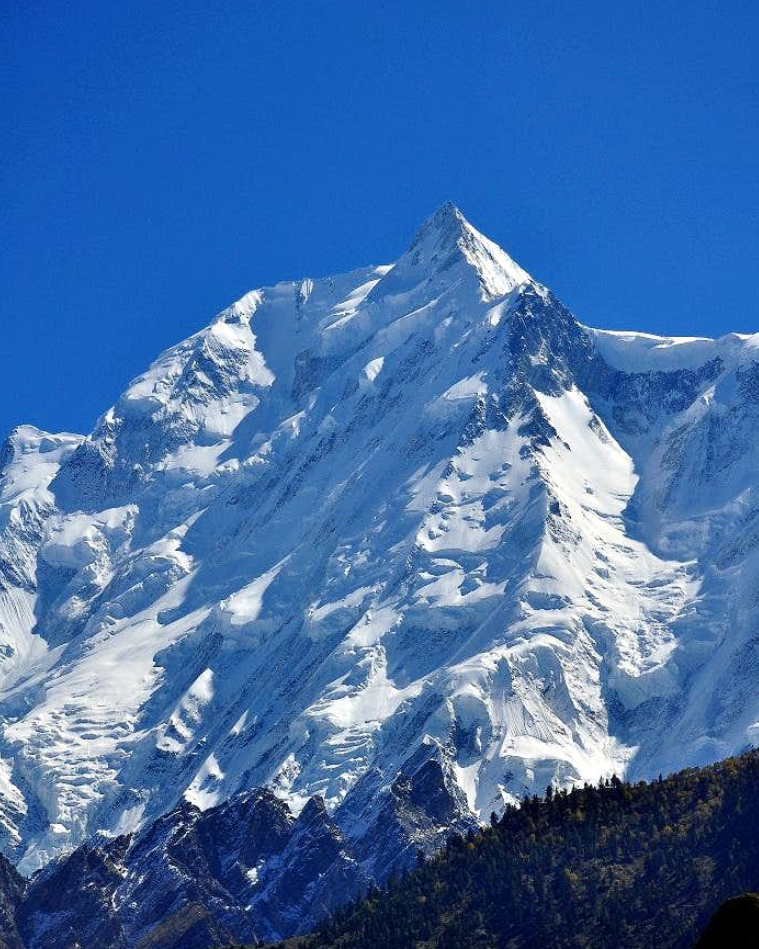

At 8,125m, Nanga Parbat in Pakistan’s Gilgit-Baltistan is the world's ninth-highest mountain, and it is dangerous. It earned its "Killer Mountain" nickname because of the high fatality rate during its early climbing history.

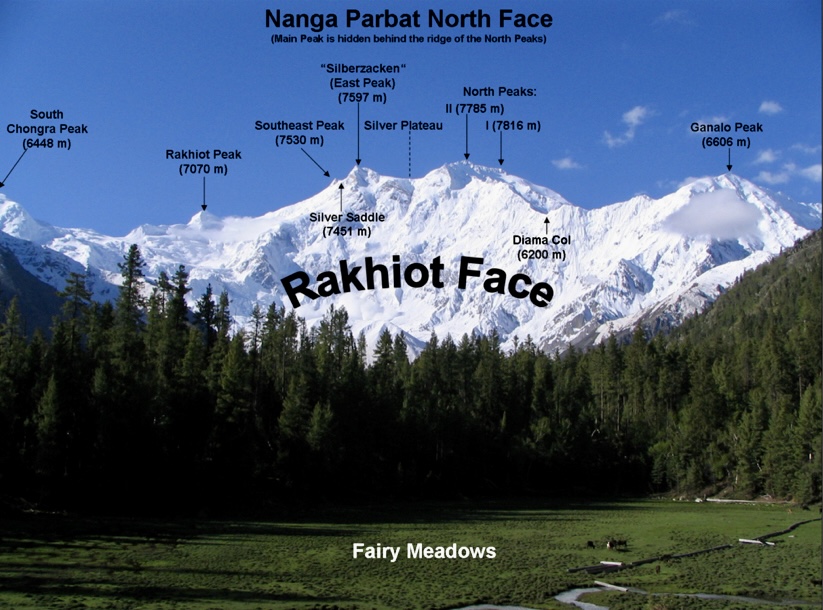

It has three main faces: the south-facing Rupal Face, the northeast-facing Rakhiot Face, and the northwest-facing Diamir Face. The Rakhiot Face is less frequently climbed than either the Diamir or Rupal Faces.

Only three teams have successfully ascended the Rakhiot Face, but more than 30 climbers have died.

The first fatalities

In 1895, Albert Mummery, Ragobir Thapa, and Goman Singh died while scouting the Rakhiot Face. They’re presumed to have died in an avalanche or fall, as their bodies were never found.

German expeditions

The Rakhiot Face became a focal point in the 1930s, particularly for German climbers, as Nanga Parbat was one of the few 8,000’ers accessible to non-British expeditions because of restrictions on Everest and the remoteness of K2.

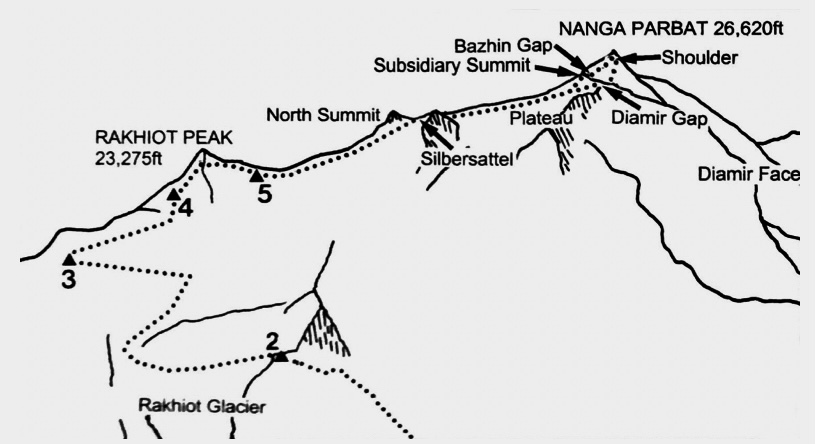

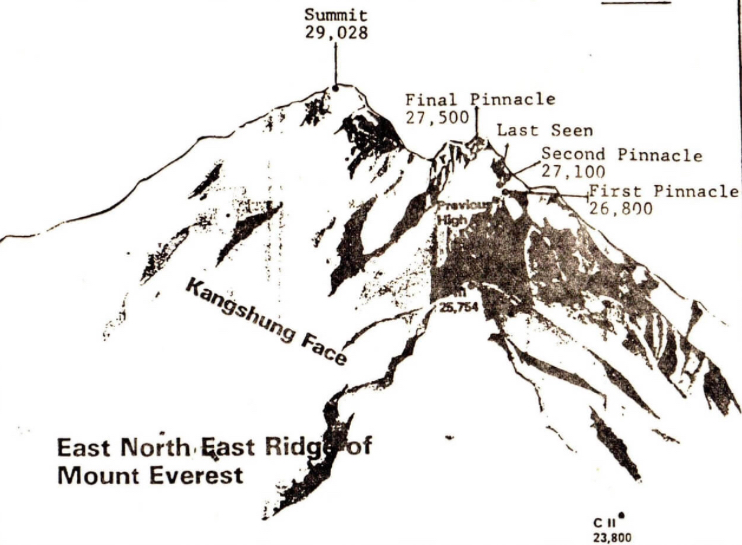

The face, characterized by the Rakhiot Glacier, Rakhiot Peak (7,070m), the Silver Saddle (7,400m), and a long ridge to the summit, presented a viable but hazardous route due to its length and exposure to avalanches and storms. The expeditions of this era targeted what would later be known as the Buhl Route, which contributed both to the mountain’s allure and its deadly reputation.

1932: Willy Merkl’s German-American expedition

The first significant attempt on the Rakhiot Face was in 1932, led by German climber Willy Merkl. The expedition, sometimes called German-American because of the inclusion of American climbers Rand Herron and Fritz Wiessner (Wiessner was German-born but became a U.S. citizen), aimed to establish a route via the Rakhiot Glacier and Rakhiot Peak.

Merkl’s party took a route to the left of the Northeast Ridge, which involved steep ice and rock. But they lacked Himalayan experience, and poor planning hampered their progress. They did not have enough porters, and bad weather added to their problems.

Peter Aschenbrenner and Herbert Kunigk reached 7,070m Rakhiot Peak but could not progress further. However, the expedition confirmed the feasibility of a route via Rakhiot Peak and the main ridge.

1934: Merkl’s second attempt

Merkl returned in 1934 with a better-prepared expedition, funded by the Nazi government. They targeted the same Rakhiot Face route as in 1932, with a minor variation.

Early in the expedition, climber Alfred Drexel died, likely from high-altitude pulmonary edema. Things only deteriorated from there.

Fierce storms caused chaos on the mountain. On July 6, Peter Aschenbrenner and Erwin Schneider reached 7,895m, one of the highest points ever attained at the time, but worsening weather forced them back.

On July 7, a ferocious storm trapped 14 team members at 7,480m near Camp 4, below Rakhiot Peak. This led to the deaths of Merkl, Willo Welzenbach, Uli Wieland, and six porters: Pintso Norbu, Nima Norbu, Dorje Sherpa, Tashi Sherpa, Dakshi Sherpa, and Gaylay Sherpa. The 1938 Nanga Parbat expedition found their bodies.

At the time, it was the deadliest mountaineering disaster in history. This tragedy, alongside later disasters, cemented Nanga Parbat’s Killer Mountain reputation.

1937: Karl Wien’s avalanche disaster

In 1937, another German expedition targeted the same route.

Led by Karl Wien, the team made slow progress because of heavy snowfall. On the night of June 14, a huge avalanche from the hanging glacier on Rakhiot Peak hit them in Camp 4. The avalanche rushed 1,200m across the flat terrace where their camp was set up, burying the tents under meters of ice and packed snow. The campsite was considered safe previously, but a sudden change in weather likely triggered the avalanche.

The avalanche killed seven German climbers (Wien, Hans Hartmann, Adolf Goettner, Martin Pfeffer, Gunther Hepp, Peter Mullritter, and Otto Fankhauser) and nine support staff members (Pasang P., Nim Tsering, Mambahadur, Kami, Gyaljen Monjo, Jigmay, Chong Karma, Ang Tsering II, and Da Thondup).

A search team led by Paul Bauer later found the tents buried under ice and snow, with one climber’s diary noting the camp’s unsafe position. Five bodies were found buried nearby. Described as having "no parallel in climbing annals" for its prolonged suffering, this disaster added to the Rakhiot Face’s deadly reputation.

1938: Paul Bauer’s cautious attempt

Paul Bauer led a German expedition in 1938, mindful of the 1934 and 1937 tragedies.

The team reached the Silver Saddle, halfway between Rakhiot Peak and the summit, but bad weather forced a retreat. Heinrich Harrer, a member of the expedition, noted the face’s challenging conditions. No fatalities occurred, but the expedition made no significant progress beyond previous attempts.

1939: Harrer’s reconnaissance

In 1939, Harrer joined a German expedition led by Peter Aufschnaiter, primarily to scout the Diamir Face. However, they also examined the Rakhiot Face, concluding that it was a viable but dangerous route. World War II and their internment in British India halted further attempts.

The 1930s saw five German expeditions to the Rakhiot Face, with at least 25 deaths and no successful ascents, underscoring its lethality.

1950: the British winter reconnaissance

The first documented winter attempt on Nanga Parbat occurred in December 1950, when a three-member British team of William Crace, John Thornley, and Robert Marsh scouted the Rakhiot Face.

Marsh descended with frostbiten toes, leaving Crace and Thornley in a tent at 5,500m. Both disappeared, likely swept away by an avalanche or caught in a storm.

"Thornley and Crace were both extremely determined," Marsh wrote for the Himalayan Club. "Thornley, for instance, marched 265km to Nanga Parbat over the Babusarr Pass, wearing a pair of gym shoes, in six days, and was in no way fatigued at the end. They were a fine pair of friends, and it took an expedition of this sort, where we lived close, in difficult conditions, to bring out fully the great qualities of endurance, patience, and kindness which were so characteristic of them. I am sure they wish for no better tribute than that. When they were last seen, they were still going up and still going strong."

1953: Nanga Parbat’s first ascent

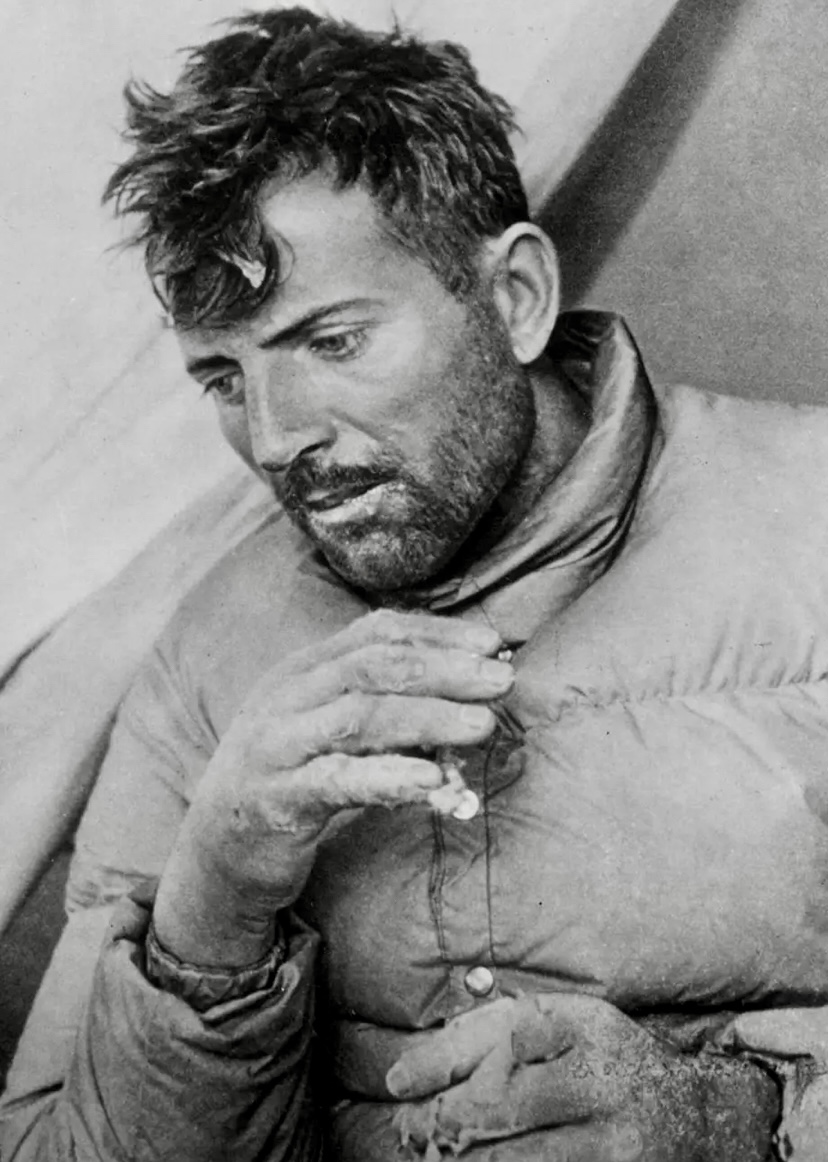

The first successful ascent of Nanga Parbat was in 1953 via the Rakhiot Face. The German-Austrian expedition was led by Karl Maria Herrligkoffer (who did not climb), whose half-brother Willy Merkl had died in 1934.

The team included Austrians Hermann Buhl, Peter Aschenbrenner, Walter Frauenberger, and Kuno Rainer, plus Germans Otto Kempter, Hermann Kollensperger, Albert Bitterling, Fritz Aumann, and Hans Ertl. It also included several (unnamed in the literature) local porters who carried supplies to Base Camp and up to Camp 4.

The expedition followed what became the Buhl Route: starting at the Rakhiot Glacier with Base Camp at 3,967m, ascending to Rakhiot Peak, traversing the Silver Saddle, and climbing the North Ridge to the summit.

On May 24, the expedition reached Base Camp. On June 10, Buhl, Kollensperger, and porters set up Camp 2 at 6,200m on the Rakhiot Glacier. Two weeks later, the climbers and porters established Camp 4 at 6,700m, below Rakhiot Peak.

On July 1, Buhl, Kempter, Frauenberger, and Ertl set up Camp 5 at about 6,950m with porter support. The porters then returned to the lower camps.

Hermann Buhl’s solo summit push

On July 2, Buhl and Kempter stayed at Camp 5 before Kempter turned back. After delays and disagreements, Aschenbrenner, the climbing leader of the expedition, ordered a retreat because of the approaching monsoon. Buhl, determined to summit, continued alone.

On July 3 at 2 am, Buhl started his summit push, carrying food, a flag, some pervitin and padutin pills, but no rope and no supplemental oxygen. His solo push was in alpine style.

Pervitin was a drug containing methamphetamine, a powerful stimulant. It was widely used by the German military during World War II to enhance alertness and relieve combat fatigue. Padutin improves blood circulation and prevents frostbite by dilating blood vessels. Yet despite the pills, Buhl did suffer frostbite.

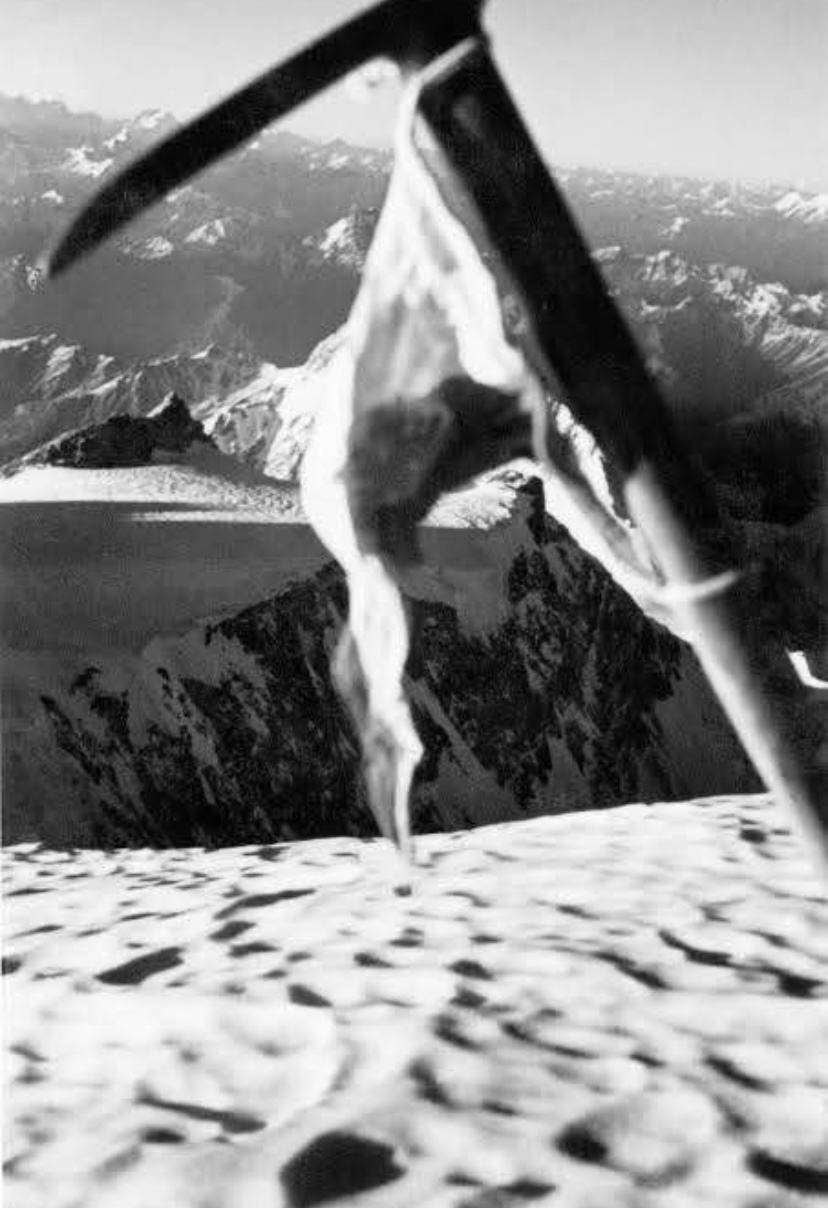

By morning, Buhl reached the Silver Saddle at 7,450m. On July 3, by 2 pm, he hit the Bazhin Gap at 7,830m, dropped his backpack, and climbed the Shoulder (8,070m). After a tough rock section, he reached Nanga Parbat’s summit at 7 pm the same day, after a grueling 17-hour climb. He left his ice axe on the summit.

On the way down, he bivouacked overnight on a narrow ledge at 7,900m. He returned to high camp on July 4 and reached Camp 5 at 7 pm after 41 hours, exhausted and frostbitten.

Buhl's solo push was a monumental achievement and is detailed in his book Nanga Parbat Pilgrimage.

Only four years later, Buhl disappeared on 7,665m Chogolisa.

Later ascents

The second ascent of the Buhl Route came on July 11, 1971, when Slovaks Ivan Fiala and Michael Orolin made the second ascent of Nanga Parbat's Rakhiot Face. Other members of the same expedition achieved first ascents of the southeast peak (7,600m) and the foresummit (7,850m).

The climbers had also attempted the Buhl Route in 1969. That time, adverse weather and logistical challenges halted them before the summit. They reached 6,950m.

This 1971 expedition remains the only successful repetition of the Buhl Route.

The Japanese Route

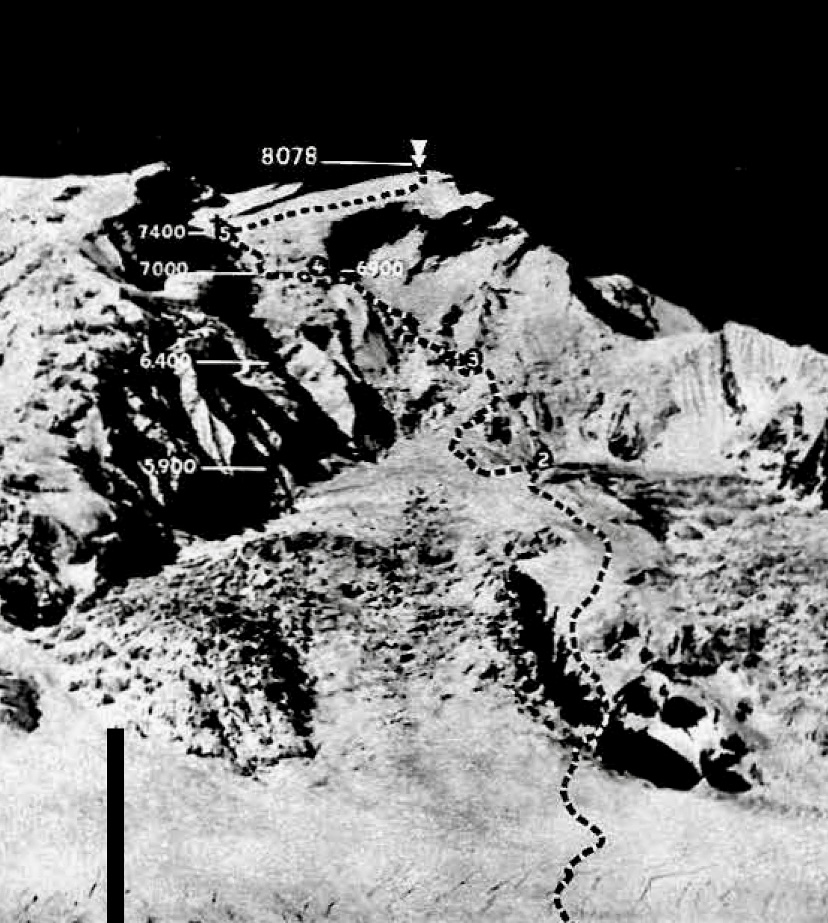

In the summer of 1995, Japanese climbers Hiroshi Sakai, Yukio Yabe, and Takeshi Akiyama established a new route on the Rakhiot Face, ascending below the East Peak and traversing to the North Ridge near the North Peak.

"After a 1992 reconnaissance to the north and a subsequent study of aerial photos, I was convinced we could climb a new route via the ridge derived from the East Peak of Silver Crag," Sakai wrote in the American Alpine Journal.

The Japanese party consisted of 10 members, though only three members had adequate experience at high altitude. Of these three, two were soon injured and unable to climb.

The expedition began on June 5 with a three-day march from Tatoo to a temporary Base Camp at 3,900m, using 100 porters to carry three tons of supplies. The main Base Camp was at 4,500m on the Great Moraine, higher than typical due to the long summit route. Acclimatization took five days, and they had established Camp 1 at 5,300m on the Rakhiot Glacier by June 11. From here, they deviated from the 1953 route.

The route from Camp 1 to Camp 2 involved a steep wall of snow and granite reaching 5,700m. The climbers faced a grade IV+ rock crack and a hazardous snow gully prone to rockfall named the Confessional Pitch because of its danger. On June 26, a falling stone injured one climber's arm, and he had to withdraw.

"As we climbed higher, we felt more and more rockfall flying down toward us, as our route led toward the upper part of this snow gully," Sakai recalled.

Inching higher, another injury

After overcoming an overhang and a jagged snow ridge, they set Camp 2 at 5,900m on June 25. Above Camp 2, at 6,300m, a 300m ice tower posed a major obstacle. The team navigated a vertical slit in the ice, climbing four pitches at 70°. Beyond this, the route eased into knee-deep snow along a ridge, leading to Camp 3 at 6,700m, established on July 4.

On July 7, Tamura was injured by a falling stone at the Confessional Pitch, requiring a three-day rescue. With only six climbers left, the team abandoned plans to traverse Nanga Parbat and rested until July 12.

The route to Camp 4 traversed the Silver Saddle’s flanks, tackling Yabe’s Crack, a 50m grade V climb. By July 18, after navigating 800m of snow and rock, Camp 4 was set at 7,350m near the Silver Plateau.

The summit push

On July 22, Sakai, Yabe, and Akiyama left high camp toward the summit. However, soon after, they returned to Camp 4 because Akiyama felt pain in his chest, and Yabe’s fingers and toes had gone numb with cold. During that night, they took oxygen to regain their strength.

On July 23, Sakai, Yabe, and Akiyama summited at 5:13 pm via a new route, after a grueling climb through the Silver Plateau and a steep summit wall. They faced exhaustion and worsening weather but reached the top.

The descent was tough, with a bivouac at 7,700m in a snowstorm. The team returned to Camp 4 after 39 hours and reached Base Camp on July 28 amid bad weather. Despite injuries and setbacks, the expedition succeeded, marking a new route on Nanga Parbat’s North Face.

This marked the third successful ascent of the Rakhiot Face and introduced a more direct but equally challenging alternative to the Buhl Route. No further ascents of this route have been recorded.

2008: a new route attempt

In the summer of 2008, Italian climbers Simon Kehrer, Walter Nones, and Karl Unterkircher attempted a new route via the Rakhiot Ice Wall.

The team arrived at Base Camp in late May, spending weeks acclimatizing and observing the Rakhiot Face, noting its avalanche-prone seracs and crevasses. On July 14, they began their summit push at 10 pm, hoping to minimize avalanche risk by climbing at night when it was coldest.

They cached a tent at 4,500m and began climbing again after midnight on July 15, navigating 60° ice and a near-vertical M4/5 mixed wall to 5,700m. After tackling deep snow and a serac, they reached 6,300m by 4 pm, where Unterkircher fell into a crevasse and died. Kehrer and Nones attempted a rescue but found his body buried under snow. Unable to recover it in dangerous conditions, they retrieved his gear and continued up.

Opting against a risky descent, they climbed toward the Silver Plateau via a longer, easier route through avalanche-prone slopes and steep mixed terrain. A storm on July 17 slowed progress with waist-deep snow, forcing bivouacs at 6,650m, 6,800m, 7,000m, and 7,300m.

They reached 7,500m on July 21. On July 22–23, they skied down the Buhl route in poor visibility, surviving two avalanches. Eventually, a Pakistani Army helicopter airlifted them from 5,400m to Base Camp on July 24. Recovering Unterkircher’s body was deemed impossible.

The route, named Via Karl Unterkircher (3,000m, IV-V M4+ 70°-80°), was dedicated to their fallen friend.

Since its last ascent in 1995, the Rakhiot Face remains unclimbed to the summit. Of the 80 people who have died on Nanga Parbat, more than a third perished on the Rakhiot Face.

You can find the climbing history of the Diamir Face here, and the Rupal Face here.

Perhaps the most famous ship in exploration history, the Fram was designed specifically for the challenges of polar navigation. With her rounded hull, she withstood the crushing ice that shattered the likes of Shackleton's Endurance, rising up over the ice instead of being pinned by it. Her design, however, which made her so perfectly adapted to her line of work, also made her roll horribly in the open sea, inducing seasickness.

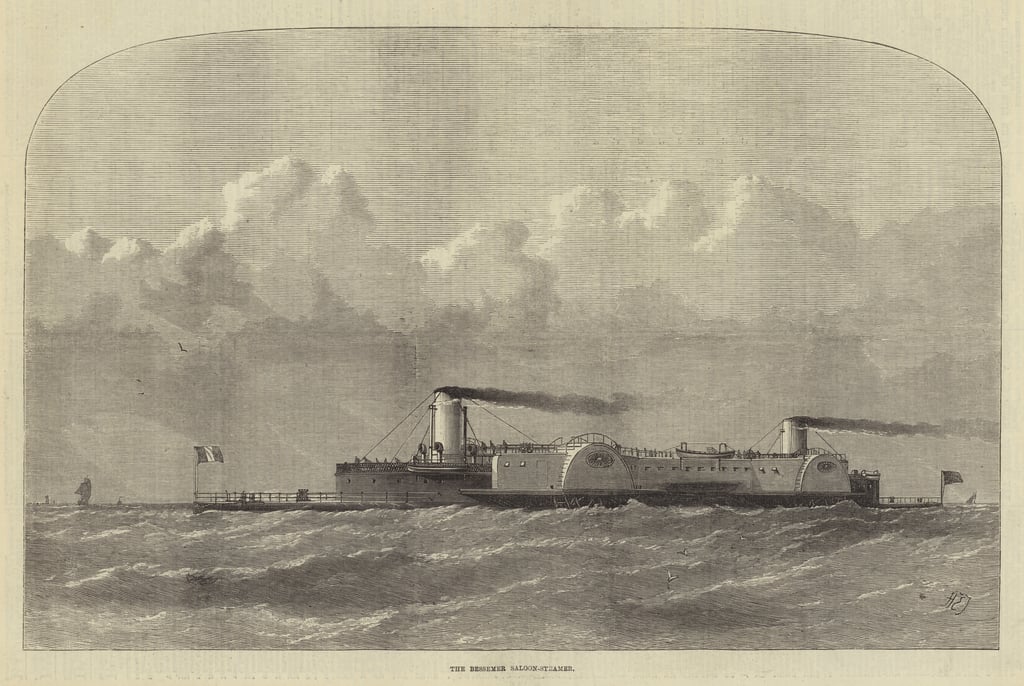

The SS Bessemer was basically the exact opposite of the Fram. While she was engineered against seasickness, she also seemed to be engineered against seaworthiness. Or perhaps some jealous oceanic deity, seeing humanity attempt to conquer the limitations he'd placed upon their encroachment in his domain, cursed the poor ship.

Cursed or no, the SS Bessemer certainly had an eventful career.

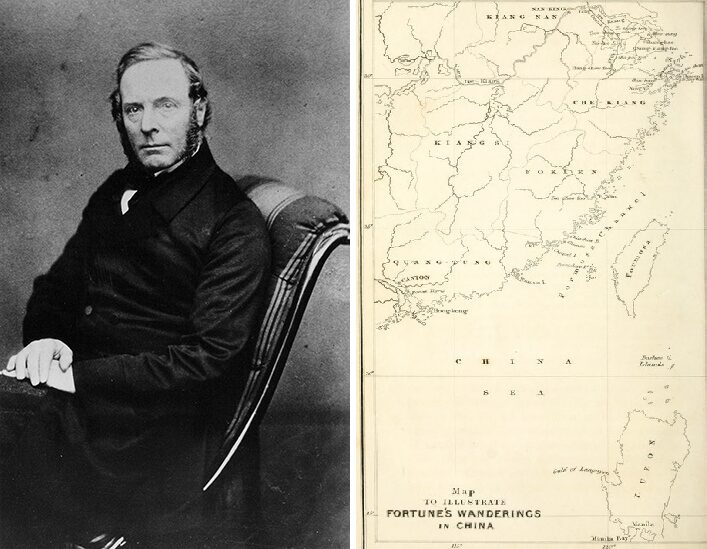

The eponymous Bessemer

Henry Bessemer was born in 1813 on his Huguenot inventor father's small Hertfordshire estate. After fleeing the French Revolution, his father settled in England and made his money from his inventions. Henry took after his father, fascinated by machinery and driven to improve upon the mechanisms he observed. He moved to London at 17 to seek his fortune and immediately began experimenting.

His first big success was a steam-powered machine to manufacture bronze powder. Originally, his only ambition with the experiment was to make gold paint for his sister, a watercolor artist. But the process and manufacturing machines he developed made enough to support him while he continued inventing.

If you've heard the name Bessemer, you've heard it in connection with his most important invention: the Bessemer process. In terms of Industrial Revolution inventions, it ranks among the steam engine, the telegraph, and the spinning jenny.

What Bessemer invented was the first way to produce steel quickly and cheaply. Bessemer steel built the railroads, bridges and skyscrapers of the next century, and made Bessemer a wealthy man. But he wasn't done inventing.

The steel magnate and mal de mer

In 1868, Sir Henry (we will call him that moving forward, to avoid confusion between the inventor and his ship) took a channel steamer from Calais to Dover. While the English Channel crossing through the Strait of Dover, as this route is called, is and was very common, it wasn't easy. While it took less than a day on the steamship ferries, the shallow channel with its powerful, strange currents was notorious for causing seasickness.

"Few persons have suffered more severely than I have from sea sickness," Sir Henry wrote in his autobiography. The 1868 crossing, followed by a 12-hour train journey, left him temporarily bedridden and, it seems, somewhat traumatized. Determined to rid the world of this scourge, he set his inventive mind to work.

The principle was deceptively simple: A suspended cabin within the ship, which, mounted on gimbals, would remain stable while the outside of the ship was tossed about by the waves. He built a tiny model, "small enough to be placed on a table," and rocked it back and forth using clockwork. It was probably rather adorable.

In December 1869, Sir Henry patented his design and set about building it.

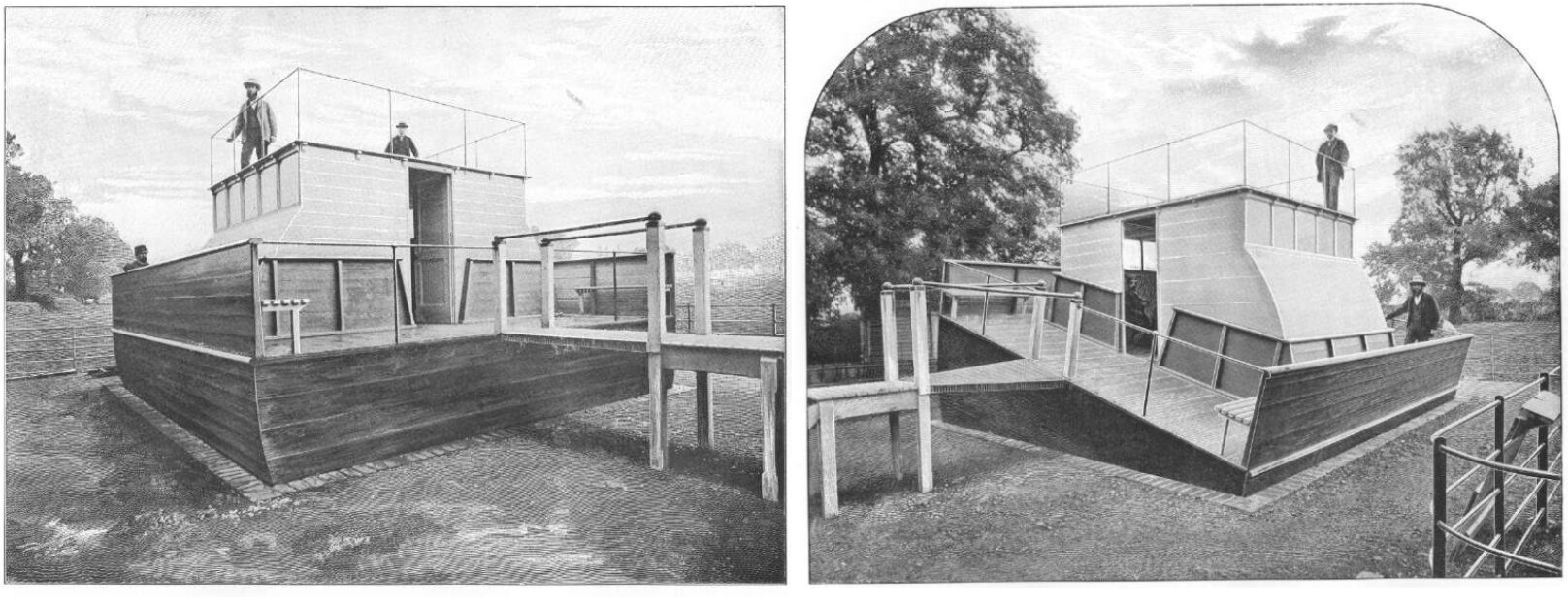

The backyard ship

Rushing into the project, Sir Henry paid a shipbuilder to construct a small steamer for the modern equivalent of over $430,000. No sooner had he done so than he realized he needed to alter his initial design, and the half-built ship wouldn't accommodate the changes. He sold it off for a third of what he'd paid and instead built another model.

Sir Henry was unwilling to actually go out to sea for testing, so he built the middle of a small ship in his backyard. His new design included a steersman. He would manually adjust the level of the cabin by turning a handle to match a spirit level. The motion of the handle would then control the hydraulics.

Sir Henry invited scores of wealthy and prominent friends and fellow inventors to experience the model. They all pronounced it a success, and papers on both sides of the Atlantic reported excitedly that soon seasickness would be a thing of the past.

Building the SS Bessemer

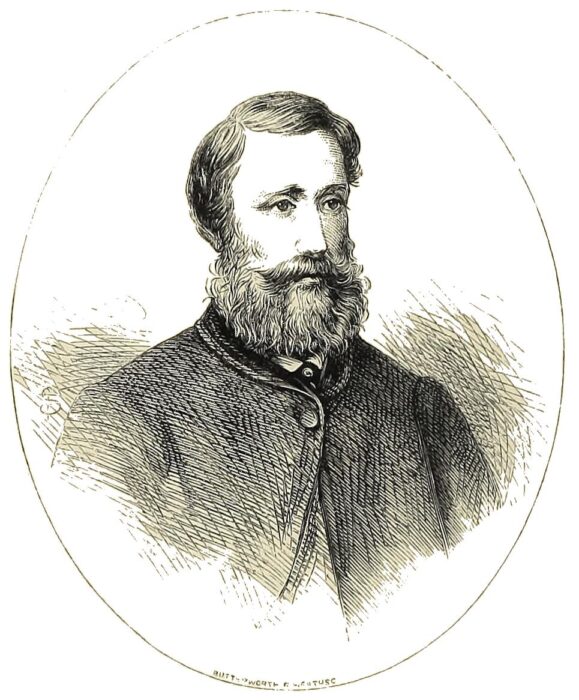

This steersman design satisfied Sir Henry, who formed a joint-stock company and raised $340,000, roughly $34 million today. Joining him in the company was Sir Edward James Reed, who'd been the Chief Constructor for the Royal Navy, and would go on to become a railroad magnate and a member of Parliament.

Designing the ship part of the SS Bessemer was probably somewhat of a low point for him. He'd just bitterly resigned from his Naval command. Parliament had undermined and insulted him by funding the HMS Captain, designed by his detested rival Captain Cowper Phipps Coles, without consulting him. He had something to prove when he decided to join the ambitious new venture.

Sir Henry and Sir Reed sent their plans to Earle's Shipbuilding Company in Hull. Sir Henry continued to bleed money into the project just to keep it afloat.

When the ship was nearly complete and was moored outside Earle's Shipbuilding Company in Hull, a late October gale struck the coast. Too long to be anchored in the regular way, she'd been chained horizontally by both stern and head. As a result, her long side met the full force of the wind, and she was torn from her moorings and driven onto the muddy bank.

She escaped the embarrassing incident without major injury, and they were able to coax her back into the water and finish construction. Finally, after even more personal financial outlay, the ship was insured, and a commander, a Captain Pittock, was found. The maiden voyage of the SS Bessemer was scheduled for May 8, 1875.

A trying trial run

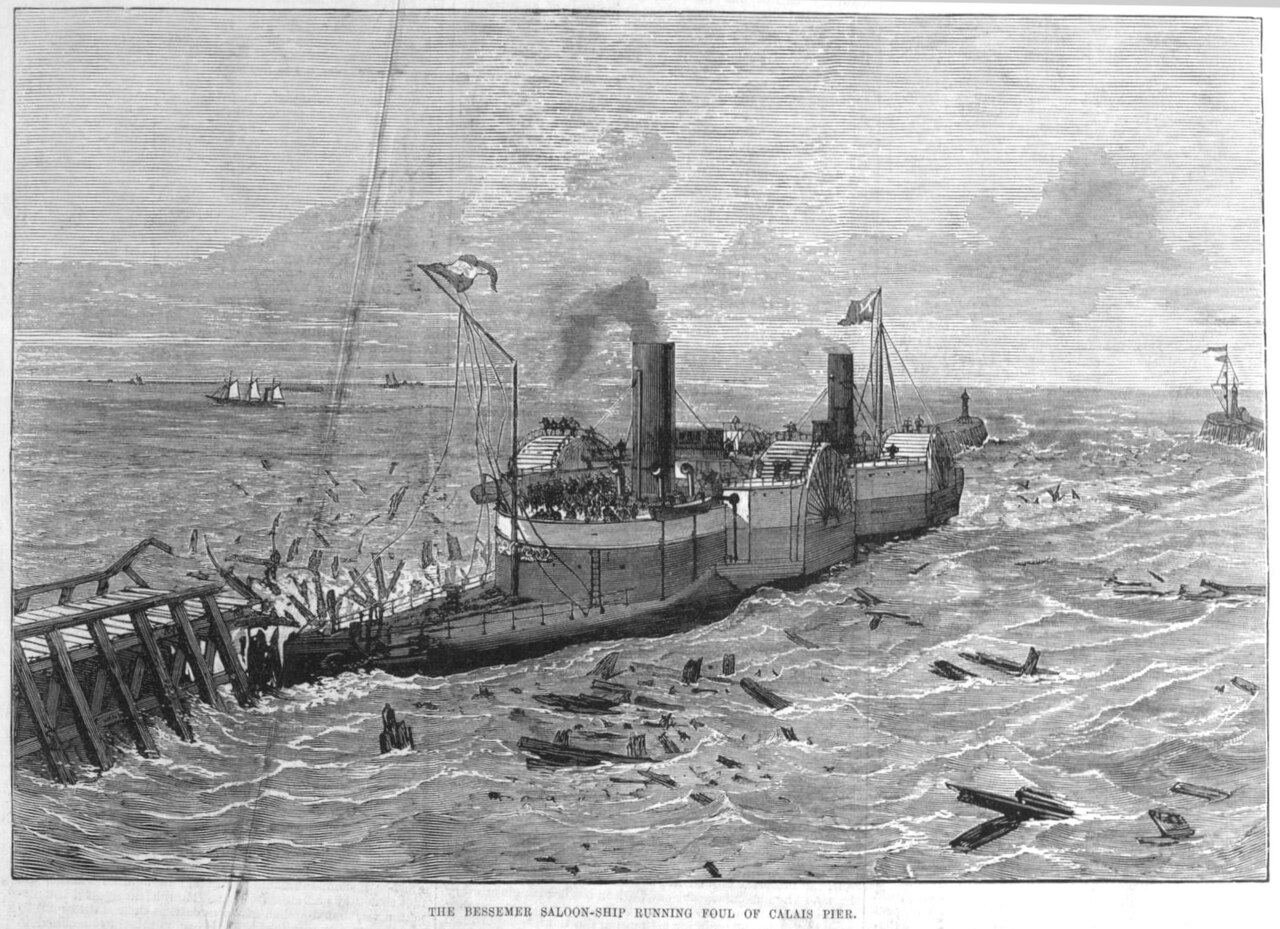

The company wisely decided to perform a trial run before the public debut in May. A few weeks in advance of the date, Captain Pittock took the SS Bessemer out of Dover, planning to dock at Calais and then return.

Unlike many maritime mishaps, weather could not be blamed for what followed. As Sir Henry himself described, the SS Bessemer approached Calais "on a beautiful calm day, in broad daylight, at a carefully chosen time of the tide, and with all the skill of the best Channel navigator."

Whereupon she crashed into the pier. Her paddle wheels slammed into the pier, causing $3,800 in damages and destroying the paddle wheels. Captain Pittock had to go before the consul in Calais, where he swore that the ship simply "did not answer her helm."

She was fitted with replacement paddle wheels, and Pittock managed to carefully inch her back out of the port and limp home to England.

Sir Henry and the company decided it was too late to postpone the May 8 launch. Instead, while the SS Bessemer was being repaired, her creator had the saloon fixed in place, completely defeating the whole purpose of its existence.

Failure continues

Without a doubt, Sir Henry was an incredibly intelligent man with a gift for metallurgy in particular. But he was not a shipwright. The balance of weight in a ship is both important and delicate. The holds of contemporary sailing ships were carefully packed and re-packed to ensure the weight was perfectly distributed. Getting this wrong could negatively affect the sailing abilities of even a very seaworthy vessel.

The SS Bessemer, built around an unwieldy cabin and hydraulics, was already not the easiest sailor. With a great weight constantly shifting the center of gravity, she was practically unsteerable, with dangerously unpredictable movement.

Worst of all, she wasn't even seasickness-proof. Reporting on her maiden voyage, a Wisconsin newspaper wrote that while the design seemed to work in the bay, once she reached the open channel things went awry: "Pitched about by the raging sea, the cabin floundered wildly, and the passengers parted with their victuals as passengers have ever been wont to do."

On her first journey from Hull, where she was built, to Gravesend, she gobbled up coal at an amazing rate. One passenger reported that the saloon itself moved as designed, but either due to mechanical or human error, it didn't respond fast enough to actually negate the movement of the ship.

On the 8th of May, with the first passengers on board and just as ill as always, the SS Bessemer inched into the port of Calais. All breaths were held as Captain Pittock gave his orders-- and the ship failed to respond. The SS Bessemer crashed into the Calais pier for a second time, as Sir Henry put it, "knocking down the huge timbers like so many ninepins!"

The final demise of the SS Bessemer

Sir Henry had sunk a great deal of his personal fortune into developing, building, re-building, and rebuilding a second time. It was an unwillingness to throw good money after bad, not a lack of belief in the concept, that caused Sir Henry to finally pull the plug.

At least, that's what he himself said. That his saloon had proved an entire failure, "nothing could be more absolutely untrue," Sir Henry insisted. It's almost sweet how much he believed in the viability of the wretched little ship despite all evidence to the contrary. At any rate, he never admitted that the concept itself was flawed.

But the second Calais incident killed the SS Bessemer commercially. The bankrupt Bessemer Saloon Steamboat Company was sold off, and the SS Bessemer was sold for scrap. Sir Reed had the saloon itself removed from the ship and installed as a billiards room on his estate in Kent.

Henry Bessemer continued to invent, with varying degrees of success. In 1893, he attempted to build a sun-powered furnace that he promised would reach up to 33,000˚C. However, he gave up after a lens maker failed to produce the required lenses.

In 1889, Sir Reed's estate became Swanley Horticultural College, a women's agricultural school. The beautiful, ornate saloon of the SS Bessemer was used as a lecture hall.

On March 1, 1944, Swanley Horticultural College was bombed in a German air raid. The saloon was destroyed by a direct hit. Only a few pieces of paneling, rescued by local residents, survive.

Humanity has yet to invent a seasick-proof ship, but we do have over-the-counter dimenhydrinate now, which has always worked for me, anyway.

The ninth-largest mountain in the world, Pakistan's 8,125m Nanga Parbat has three main faces: the south-facing Rupal Face, the northeast-facing Rakhiot Face, and the northwest-facing Diamir Face.

On June 24, David Goettler, Tiphaine Duperier, and Boris Langenstein summited via the Schell Route after an 18-hour, alpine-style push from Camp 3 at 6,800m. From the summit, Duperier and Langenstein made the mountain's first complete ski descent, including the entire Rupal Face, according to Montagnes Magazine. Goettler paraglided from 7,700m to Base Camp.

This article will explore the climbing history of the Rupal Face.

The tallest mountain face