Did you know that “thrawn” is the ability to make the most of whatever you’ve got?

Did you know that Beira, the Queen of Winter, is the mother of all Scottish gods and goddesses?

You’ve had to pause for reflection twice within the first 10 seconds of the film if, like me, you didn’t.

Don’t expect that effect to go away. Lesley McKenna and Lauren MacCallum may not be the Queens of Winter — but they’re pro snowboarders and they've got a lot to say. Contemplative narration dovetails here with an ardent style of riding that's hard to find on piste.

Would you ride that? Yeah, me neither — but then again, I don’t have thrawn.

Stubborn energy

“Stubborn is definitely part of it,” MacCallum says. “A transformative energy, a powerful energy, aye — very needed in these times. The struggle — the thrawness.”

This Patagonia joint is all about the athletes’ deep-rooted backgrounds and contagious personalities. You don’t have to watch much of it to get a strong infusion of both qualities — but you should, because they’re both colorful and compelling.

As much as Thrawn is the story of two athletes, it’s also the story of their town. Aviemore, Scotland is situated in Cairngorms National Park, and it’s a focal point of the country’s ski scene. McKenna knows it well — it’s where her father worked as the first professional ski patroller in the United Kingdom.

Don’t miss wipeouts, sketch moments, and highlights from the Olympian’s long career in the bindings. And hang on for a statement about the future of snow sports in Scotland. MacCallum delivers a snarling, steadfast, aspirational message on the climate change reshaping the country’s famous highlands.

Noting statistics on snowfall decline, she says, “I’m sick and tired of complaining about it in the pub, basically. It brings a sense of unease. We’re gonna have to roll up our sleeves and do it for our goddamn selves.”

Whether or not you lace your boots and cinch your bindings with thrawn each day, you’ve probably felt its call. Watch this short docu to get a booster shot of the mojo that makes these Scottish snowhounds tick.

American ultrarunner Camille Herron has set another world record.

This time, Herron ran 560.33 miles (901.8km) to set a new women’s six-day world record at the 2024 lululemon FURTHER event in La Quinta, California.

The event ran March 6-12 to coincide with International Women’s Day on March 8. New Zealand’s Sandra Barwick set the previous record of 549.063 miles in Australia in 1990, a record that’s stood for 34 years.

Herron broke that record by more than 11 miles and also achieved at least 12 interim world records and milestones along the way. Her effort comes out to an average pace of at least 15:22 per mile over the entire six days. This includes hours of stopped time, which Herron used for sleeping, resting, eating, drinking, and more.

The race was held on a 2.55-mile loop made up of largely dirt. Herron ran 220 laps.

Here are the records, world bests, and other milestones that Herron hit en route. This was Herron’s approximate record progression through the six days:

- 48-hour USATF American road record – 247.7 miles (Her IAU world record and USATF American track record still stand at 270.5 miles from her 2023 effort at the time-based event.)

- 300 miles – 59:54:58 (hours:minutes:seconds)

- 500 kilometers – 62:50:45

- 3 days – 342 miles

- 600 kilometers – 81:23:38

- 400 miles – 88:34:26

- 4 days – 429.8 miles

- 700 kilometers – 98:33:59

- 800 kilometers – 117:44:55

- 500 miles – 118:19:17

- 5 days – 501.7 miles

- 900 kilometers – 142:40:58

- 6-day IAU world best performance benchmark – at least 560 miles

This story was first published on iRunFar.

Kilian Jornet’s reputation precedes him. You don’t need me to tell you about the career of the most accomplished ultrarunner ever.

But he’s racked up some mileage by now. In 2023, he took 84 days off due to injury.

Think your stats measure up to the GOAT? Here’s what Jornet did this year — according to his trusty training spreadsheet.

View this post on Instagram

Canadian philanthropist and real estate investor Kim Bruneau had already found fertility through diving. Now, she wanted a world record.

So she plunged into the deep end. Bruneau first discovered her abilities in freediving during a recent trip to Mexico. According to the Toronto Sun, she found during a training exercise that she could dive 27 meters on one breath.

Bruneau then partnered up with an underwater photographer and voila — a beautiful shoot at a record depth.

Bruneau dove 40 meters in Nassau, Bahamas with photographer Pia Oyarzun on Dec. 5. She planted herself on a sand knoll amid a school of sharks and handed over her mask and breathing apparatus to Oyarzun. Then, wearing a dramatic red dress, she posed for the camera. A diver just out of the picture regularly returned to let Bruneau take a breath or two.

“The memories it created, it’s awesome,” she said. “I’ve done modeling for a couple of years but these are epic. This is the kind of portfolio I want to have.”

Bruneau and Oyarzun combed the deeps to another set or two, including a sunken ship, before surfacing.

Hidden weights kept her down

The multi-talented model wore concealed gear totaling around 6 kilos to stay down while posing. And she observed strict breathing routines involving nitrox and emergency regulators to avoid decompression illness, the Toronto Sun reported.

Amazingly, it was diving that also first made Bruneau a biological mother. She had years-long fertility struggles. IVF treatments and other techniques were unhelpful, and the condition only subsided when she first started diving.

Bruneau’s first daughter is adopted, and her second daughter Ella Rose is in her first year of life.

“I stopped all the things I thought would help (get me pregnant) and I just did things that made me happy,” Bruneau said.

She broke the previous record by around 10 meters.

Here is Bruneau's Instagram post describing the spectacular shoot.

Daniel Winn sits at his modest kitchen table, waiting on word from his agent while playing chess against himself.

“It’s a very exciting time,” he says. “[My agent] might actually, at this very moment, be calling brands…seeing who’s kinda interested and who’s not so interested.”

A collegiate distance runner whose career was once described as “moderately exceptional” by a local publication, he is now chasing the dream of going pro. Or as narrator Jeff Merrill puts it, “pursuing the five-figure contract of his dreams.”

Winn reflects. “I don’t have a very good understanding of my value,” he says.

Welcome to LIMITS — the story of a young track and field athlete resigned to the trenchant career limbo only fringe sports can promise.

Prepare for sardonic overload. Minutes into the film, I actually felt compelled to Google Winn to make sure he was real; the interviews are perfect.

If the producers could have seen me do it, they would have cackled with vindication. There are films about athletes where grit and determination are a brave protagonist’s only weapons against an uncaring world. This is not one of them.

Winn finishes a workout he complains and fawns his way through. Turns out it’s his lucky day: buy two, get one free on post-workout beverages at the corner store. And they’re hiring, “so if this running thing doesn’t work out for me,” Winn winks into the camera, “I know where to go.”

LIMITS is adept at using the macro narrative of the struggling young athlete as its main implement. But it really twists the knife with the subtleties.

The morning after a frustrating race, he gets his toaster down from a shabby shelf above his oven to make frozen waffles. He’s telling us how his friends keep insisting that his career woes are due to “bad timing.”

The camera frame just so happens to capture a magnetic knife holder with a single cheap steak knife on it. He laments that there are only two waffles left.

“I don’t know, it’s just tough,” he purses his lips.

As Winn spirals away from what he calls his “life goal,” many professionals among his cohort (interviewing as themselves) flourish. But most of them appear to have no clue why or how they’re doing it. Their obliviousness renders Winn’s situation even more pathetic.

“I definitely had no idea, career-wise, what I was going to do after school,” Sinclaire Johnson says, “so I’m kinda glad the pro running thing worked out because it’s buying me some time to figure out what I’m going to do with the rest of my life.”

LIMITS holds delights far too profound to make spelling out the conceit worthwhile. Don’t miss when Winn compares himself to the brilliant but tragic writer Sylvia Plath.

And if you’re offended by attacks on delusions of grandeur, don’t press play.

In 2022, Eleanor "Elsey" Davis gained notoriety on the international trail racing scene, racking up wins and becoming a North Face athlete.

And now, just six days into the new year, she's already made a new running record.

On Jan. 6, Davis broke the women's winter Bob Graham record, completing the classic trail in 20 hours and 21 minutes. That beats the previous women's record by nearly an hour and a half, which was established in Dec. 2018 by Sabrina Verjee. She completed the trail in 21 hours and 49 minutes.

For the uninitiated, the Bob Graham Round has a well-deserved reputation as a grueling, difficult trail. This Lake District fell running challenge (also known as hill running) traverses 42 fells over 106km, with 8,230m of elevation gain.

The challenge is named after Bob Graham, the runner who first completed the route in under 24 hours back in 1932.

Just a few weeks ago, two other runners each broke the solo, unsupported winter Bob Graham Round record — within 24 hours of each other.

She’s away! Elsey setting off at 22.00 on her Winter BG in good spirits. Bit wet & windy atm but should clear away later. Go well Els. pic.twitter.com/jCjVSlZxdV

— Duncan Richards (@duncsjr) January 5, 2023

Davis earns place in the spotlight

Elsey Davis could fill a trophy shelf with the trail races she won last year.

In July, she finished first among women at the Eiger Ultra Trail in Switzerland. In August, she won the Scafell Marathon and ran for Britain at the World Mountain and Trail Running Championships.

Still going strong, she took home a win from Ring of Steall in September. Then Davis got an invite to the Golden Trail World Series for the first time, where she finished third after three days of racing in the Azores.

Ver esta publicación en Instagram

As if all that wasn't enough, she managed to finish eighth in the UTMB OCC, and joined Britain's team for the World Mountain and Trail Running Championships in the fall.

"This phenomenal year of running happened in parallel to Elsey’s demanding work life as a trainee GP, and comes off the back of her spending much of 2020 working on the COVID wards," the UK's Trail Running Mag wrote.

In 2020, Davis had planned to run in the London Marathon. She ended up treating COVID patients instead, the UK's Runner's World reported.

Two fell runners moving in opposite directions each broke the solo, unsupported winter Bob Graham Round record within 24 hours of each other, according to UK Hillwalking.

The outlet reported Paul Wilson set a time of 22 hours, 54 minutes on Thursday, Dec. 15. Shortly after that, on Friday, Dec. 16, James Gibson set a new record of 21 hours, 12 minutes.

"What a day! The conditions were perfect for winter running with lots of hard frosted ground. I didn't have a schedule; I just went with the flow and enjoyed it," Gibson told UK Hillwalking. "I ran strongly and passed Paul [Wilson] on Yewbarrow, stopping for a selfie before both pushing on in our opposite directions."

"Temperatures fell to about -10˚C, and my bottles froze in the night. With all the high becks frozen over too, it made getting water pretty hard. My legs tired over the last section, but I was happy to keep going and get back to Keswick in the time I did," he went on.

For the purposes of the record, "winter" refers to any time between Dec. 1 and the last day of February, UK Hillwalking reports.

Shane Ohly, the founder of Ourea Events, set the previous solo unsupported winter record at 23 hours, 26 minutes on Dec. 2020.

A famously grueling route

The Bob Graham Round is a Lake District fell running challenge which traverses 42 fells over 106km, with 8,230m of elevation gain thrown in for good measure. The challenge is named after Bob Graham, the runner who completed the route in under 24 hours back in 1932.

According to Fastest Known Time (FKT), runners traditionally tackle the Bob Graham Round supported and with the assistance of pacers. A solo, unsupported winter attempt is another beast entirely. Only four runners have completed it: Martin Stone, Shane Ohly, and now Paul Wilson and James Gibson.

FKT lists the current supported male Bob Graham Round record holder as Jack Kuenzle with a time of 12 hours, 23 minutes and the supported female record holder as Beth Pascall at 14 hours, 34 minutes.

Here's a short film about the Bob Graham Round Saloman put out a few years ago.

By anyone's standards, 222kph is speedy. If the only thing propelling you is the wind, it's unheard of — until now.

That's because pilot Glenn Ashby and Emirates Team New Zealand stoked their land yacht Horonuku up to 222.4kph on a lake bed in South Australia. The still-unofficial feat effectively broke the previous wind-powered land speed record of 202.9kph (set by Richard Jenkins in 2009).

The Horonuku's crew hit the milestone on Dec. 11 at Lake Gairdner. It took advantage of seasonal 22-knot South Australian winds to push the land yacht to unheard-of speeds. Conditions were gusty, making piloting difficult.

“The team and I are obviously buzzing to have sailed Horonuku at a speed faster than anyone has ever before — powered only by the wind," pilot Glenn Ashby told the New Zealand Herald. "But in saying that, we know Horonuku has a lot more speed in it when we get more wind and better conditions."

"So for sure, there is a cause for a celebration, but this isn’t the end," Ashby continued.

The Auckland-based Māori tribe hapū Ngāti Whātua Ōrākei named the Horonuku. In their language, it means "gliding swiftly across the land." But was the craft swift enough? Months of weather delays, rainfall, and surface water at the chosen location hampered the team's efforts.

Awaiting certification

Despite those setbacks, the Horonuku's internal GPS data indicates it broke the record. But official verification is up to land yachting's governing body: the Federation Internationale de Sand et Land Yat (FISLY).

According to the Herald, Emirates Team New Zealand has 48 hours after completing the attempt to submit its data to FISLY for verification. In the meantime, the team is happy to be pushing the science needed for wind-powered land speed records toward new horizons.

"The land speed project has been a new opportunity to push the boundaries in aerodynamics, structural forces, construction methods, and materials fields,” Emirates Team New Zealand Principal Matteo de Nora told the paper.

“What is often underestimated is that the technologies we explore in challenges like this or in an America’s Cup campaign — are ultimately the foundation of tomorrow’s technology. Being ahead of the times in technology is what fascinates [us] about all the challenges faced by the team so far.”

If you don't have a silly grin on your face after flinging yourself downhill through some powder with a pair of boards strapped to your feet, you aren't doing it right.

At least, that's the argument that the short film NEOTENY makes. The title refers to the retaining of juvenile features into adulthood. Not a great thing in most circumstances, but when applied metaphorically to the idea of just getting out there and having some fun in the wintry woods — well, what's not to like?

Enter professional freeskiers Kim and JJ Vinet. Their short film explores the concept of play in three brief but jam-packed minutes of Canadian skiing.

"Like finding something that you thought was lost," the narrator intones in the opening seconds of the film as the camera glides over the snow-dusted trees of Revelstoke, British Columbia. "A longing not felt since you were a child."

And there's certainly childlike joy on display as the Vinets barrel over drops, slide through drifts, and glide gracefully around trees. The smiles are big enough to see even around the snow gear.

JJ Vinet and Danny Leblanc produced the film with Blizzard/Tecnica, so there's the occasional obligatory product closeup. But it's not egregious, and for the most part, NEOTENY is wall-to-wall backcountry goodness.

"Get out there and play," the narrator concludes as the film wraps with a final shot of Kim and JJ grinning like they just had the time of their lives.

We couldn't agree more.

Just a few decades ago, many certified scuba divers still wrote their dive tables with pen and paper. The handwritten algorithms tracked depth and time, ensuring these underwater explorers knew how to dive — and surface — safely.

The advent of dive computers in the late 1980s made that math unnecessary, and soon a majority of the world's divers had the "unattractive, chunky, grey housing" strapped to their wrists, Dive Magazine wrote.

Now, divers can get all that functionality from the Apple Watch Ultra.

On Nov. 28, Apple released the Oceanic+ app, and claims that it turns the tech company's powerful watch into a "fully capable, easy-to-use dive computer," the news release said.

Apple collaborated with Huish Outdoors to design the app for its new watch, which dropped this year. The Apple Watch Ultra already comes with depth gauge and water temperature sensors, and remains water-resistant down to 40 metres.

By pairing it with the Oceanic+ app, users get advanced features, like dive planning and a comprehensive post-dive experience.

“There’s now a companion that communicates clear and timely information to divers,” Andrea Silvestri, Huish Outdoors’ vice president of product development and design, said in the news release.

Silvestri, who led the creation of the Oceanic+ app, said "there’s never been anything like this in scuba diving before now.”

Oceanic+ App design and features

After lengthy testing, Silvestri said that the Apple Watch Ultra feels as intuitive as a dive computer. It makes it easier to focus on the experience instead of complicated button clicks or mental math.

Apple Watch Ultra is certified to WR100 and EN 13319, an internationally recognized standard for dive accessories, including depth gauges, the company said. Apple also specified that its display stays bright and visible in the water.

Wearers can customize the watch's Action button to launch the Oceanic+ app into the pre-dive screen. During a dive, pressing the Action button will mark a compass bearing. In the app's dive planner, users can set surface time, depth, and gas. Then the app calculates their No Deco (no-decompression) time — a metric used to determine a time limit for a diver at a certain depth.

A laundry list of functions continues from there. According to Apple, the dive planner presents dive conditions, like tides and water temperature. It also gives up-to-date information from external sources, including visibility and currents. Once finished diving, users can check out a collection of data about their experience, from a map with GPS entry and exit locations to other graphs about depth and temperature changes.

Silvestri pointed to the app's haptic feedback, which uses vibration to "tap" users on the wrist to deliver notifications.

'We’ve made the experience very personal," he said. "It’s like a gentle nudge to guide you.”

Oceanic+ App: pricing and availability

Interesting in trying out the app? It's available for download on the App Store.

However, you'll first need an $800 Apple Watch Ultra, if you don't have one already. It also needs to run on watchOS 9.1 paired with certain iPhones (no older than iPhone 8, for example).

Basic app functions, like depth and time, come free. But for the serious ones — decompression tracking, tissue loading, the location planner, and an unlimited logbook capacity — you'll need to pay a subscription.

That will cost you $10 USD per month, or annually for $80 per year.

If you've just been watching cats playing piano on YouTube, then you're missing out on a whole world of fun.

Robert Maddox, aka Rocketman, started his own channel four years ago, where the aging daredevil shows off his jet-powered inventions. From skateboards to go-karts to coffin cars, this mad scientist/speed demon will seemingly put flaming propulsion behind anything.

In his latest vid, Maddox decides to take his grandmother's 1960s lawn chair, strap a high-powered rocket to the back, and blow down the highway like he's running from a fleet of cops.

"It's a blast!" Maddox says. "You don't have to make super expensive things to have a lot of fun."

No doubt, Rocketman, no doubt.

Runtime: 6 minutes

The UTMB Mont-Blanc organization has announced that a participant in the PTL (Petite Trotte à Léon), one of the UTMB Mont-Blanc events, has died as a result of a fall.

This article was originally published on iRunFar.

The 2022 PTL, a 290-kilometre event with 26,500 m of ascent where entrants participate in teams of two or three, began at 8 a.m. CEST on Monday, Aug. 22, in Chamonix, France.

We sadly report that a Brazilian runner died in a fall last night during the 290-kilometer #PTL, part of the #UTMB Mont-Blanc event. https://t.co/Lf7WOEtZn7

— iRunFar (@iRunFar) August 23, 2022

The organization states that it learned of a severe accident at 1:30 a.m. CEST on August 23, during the first night of the nearly weeklong event. It occurred on an established trail between Col de Tricot and the Refuge de Plan Glacier, high above the French town of Les Contamines on the southwest side of the Mont Blanc massif.

According to this year's PTL course map on Livetrail, the live-tracking application, this was somewhere between kilometres 36 and 40 of the course. The Col de Tricot is at 2,114m above sea level and Refuge de Plan Glacier is at 2,711m above sea level. The race organization confirms that there was good weather at the location at the time of the incident.

A rescue helicopter responded to the scene, and confirmed the death of a Brazilian national. To respect the individual's family and friends, the organization will not release the victim's name.

According to the race organization, this year’s PTL saw 105 teams start. At this time the PTL continues, and each team is being given the opportunity to continue participating or not.

One year ago, a Czech runner died in a fall during the 2021 TDS race at the UTMB Mont-Blanc festival, leading to the cancellation of the race for most runners. (Those who passed ahead of the accident, roughly the top 20% of the field, were allowed to continue.)

Given the world's easy access to all human knowledge, it's often tempting to feel like everything has been discovered. Yet an objective way of measuring waves has remained elusive. A new drone company claims to have found a solution.

Given the ever-increasing number of claims from surfers about record-breaking waves, the need for a proper measuring tool becomes apparent. For example, it took over a year for Guinness World Records to confirm that Sebastian Steudtner surfed a 26m wave in Nazaré in October 2020.

Called Henet Wave, the startup has announced a drone-based method for obtaining "objective" measurements of waves in real-time.

A recently released YouTube video shows the company's first demonstration of their drone technology in collaboration with surfing pro Andrew Cotton.

This new technology, if successful, could modernize surfing competitions.

"Henet was conceived late one night in 2020 in an office overlooking the Soup Bowl in Barbados," according to the company's website. The Soup Bowl is a popular surfing spot on the island's rugged east coast.

"An article debated the XXL female wave of the year entry...[whether] the surfer needed to complete the ride in order to win the award. To us, the bigger debate should have been the ability to differentiate between a 73-foot wave and a 69-foot wave using subjective methods. Henet was born."

But a recent flight over the Weisshorn shows the siren appeal of this deadly game.

”The first time I flew, it was being alive,” wrote William Wharton in his acclaimed debut novel Birdy in 1978. "Nothing was pressing under me. I was living in the fullness of air; air all around me, no holding place to break the air spaces. It's worth everything to be alone in the air, alive."

Recently, the group Soul Flyers published a video, in which two of the best wingsuit flyers in the world, Fred Fugen and Vincent Cotte, flew over the 4,506m Weisshorn in the Alps.

The video caused a stir, thanks to the beauty of the flight over this peak. The incredible footage calls to mind William Wharton's quote above. The Weisshorn is one of the highest 4,000'ers in the Pennine Alps, north of Matterhorn and northwest of Zermatt. In particular, you can see how close the flyer was gliding to the sides of the canyon at the bottom of the mountain.

It is not the first time that the Soul Flyers have shared their love of this type of flying. On other occasions, they whizzed past the tops of the Egyptian pyramids and glided down the Eiger.

The most dangerous sport in the world

Wingsuiters typically jump either from an aircraft or from a cliff. They resemble a bat or flying squirrel, with membranes between the arms, body, and legs. They also, of course, have a parachute. During the descent under the canopy, the pilot unzips the arm wings to be able to pull the toggles that control the parachute's direction.

Wingsuiting is an advanced skill that takes many hours of experience to do it relatively safely. But even for the experts, anything unforeseen or a minor miscalculation is frequently fatal.

How this crazy, exhilarating sport began

Austrian-French tailor Franz Reichelt was an inventor and parachuting pioneer. He was the first to carry out a wingsuit jump, wearing a combination of a parachute and wings. Reichelt had asked for a special permit to jump from the Eiffel Tower in Paris. On a cold February 4, 1912, at 7 am, the 33-year-old Reichelt launched himself from the first platform of the tower. His parachute failed to deploy, and Reichelt died immediately when he crashed to the ground.

The dangers

One of the most frequent accidents occurs when the wingsuit flyer hits the tail of the aircraft during launch. This happens very frequently. Also, when several flyers are in the air in close proximity, it is important not to interfere with the airflow of the others. This can cause turbulence and a high-speed crash.

When the wingsuit flyer jumps from a cliff, the first seconds are critical to gain stability and pick up speed for greater control. At any time, the wind can abruptly change direction, or the jumpers may miscalculate how close they have swooped to the side of a mountain. This all happens in a thousandth of a second.

Even BASE jumping is unavoidably dangerous. The list of deaths grows every month. There are many accidents every year, and practically all of them are fatal.

Since 1981, more than 400 people have died, many of them during wingsuit flights. The death rate for wingsuiting is an astonishing 1 death per 500 jumps. The most recent tragedy occurred just days ago in the Julian Alps. Bad weather has grounded rescuers for the time being, though it is not a rescue but a body retrieval.

The famous free solo climber and BASE jumper Dean Potter and his partner Graham Hunt died in 2015 during an illegal wingsuit jump in Yosemite. The pair crashed after launching from Taft Point at an altitude of 2,300m. In 2011, Potter achieved what was then the longest flight for wingsuit BASE jumping (7.5 km). He was also the first to BASE jump with a dog, his Australian cattle dog named Whisper.

The unforgettable Valery Rozov combined BASE jumping and wingsuiting with mountaineering. He had more than 10,000 jumps in his career, many of them spectacular. He flew from an active volcano in Kamchatka, from Mount Ulvetanna in Antarctica, from 6,275m Huarascan, from Cho Oyu from 7,700m, and from the North Face of Everest at 7,220m.

In 2004, Rozov and his climbing partners opened a new route on the west face of 5,800m Amin Brakk in the Karakorum. Rozov then BASE jumped from the top.

He died in November 2017 jumping in a wingsuit from Ama Dablam. After a bad launch, he fatally hit a ledge.

A trip up any of New Hampshire's modest 1,220m "high" peaks amounts to a hop, skip, and a jump for most visitors. For one avid hiker in the state, the figure of speech takes on the primary form of ascent.

Just ask Moose, a female mini rex rabbit who lives in New Hampshire with her human, Chelsea Eason.

Eason and Moose are hiking partners. Together, the two explore trails and hunt summits.

The 7th-smallest U.S. state, New Hampshire features 48 "Four Thousand Footers," including the northeast region's highest point: Mount Washington, 1,917m.

By contrast, Moose stands about 25cm tall on her hind legs. Scaled to the height of an average human (around 170cm), climbing Mount Washington would be the equivalent of a 13,000m climb for Moose.

Eason told New Hampshire Public Radio that, as you might think, hikes with Moose tend toward the slow side. However, the casual pace affords her some special benefits.

"She'll hop around, sit and eat, and take care of herself," Eason said. "But those are the moments when I get to sit, take a breath, and figure out what she's looking at and what she's enjoying."

And Moose is far from incapable –- she keeps up on trickier trail sections, scrambling over rock slides and hopping gaps in the trail. The rabbit's full-send attitude, Eason said, helps propel her forward.

"She's kind of been my ride or die, my adventure partner," said Eason. "She's really kind of been the inspiration for me to keep going."

At the end of the day, the rabbit looks like an ideal trail partner. She doesn't appear to complain much, always brings a jacket, and seems to take care of her own nutritional needs. Plus, she's sociable and popular.

Eason said, "it's been nice" to run into other hikers, many of whom show Moose some love on the trail and on social media. The hiker bunny's Instagram following is modest, but she's becoming a bonafide TikTok star, approaching 1 million likes from about 31,500 followers.

@moosiegoosegallery @tessaviolet 's trend, but sassy hiker addition. What do you think?#yesididthat #nh48 ♬ YES MOM BY TESSA VIOLET - Tessa Violet

“TikTok was an accident,” Eason said. "I just made one or two videos, and people started really gravitating toward that."

Moose and Eason have developed their hiking technique through three years of "patience and practice." In September 2021, they completed the entire "Four Thousand Footer" circuit.

Neither shows any sign of losing the spring in her step.

A quartet of geophysicists and hydrobiologists has obtained a permit to dive beyond the 30-metre mark of Lake Cheko in Siberia. Their research, slated to begin in late February, will focus on the cataclysmic Tunguska event. It will be the deepest expedition ever conducted at the site.

Using lakebed samples, the team aims to answer a century-old question posed by the leader of the first Tunguska research expedition, mineralogist Leonid Kulik. His question was this: If a meteorite caused the explosion, where is the epicenter of its crater and the extraterrestrial matter from it?

The Tunguska event and conflicting research

In July 1908, a meteoroid measuring 50-60 metres in diameter plunged through the atmosphere above the Siberian taiga, catalyzing the 12-megaton Tunguska explosion. Experts estimate that the blast decimated some 80 million trees and dispatched at least three human beings. It is Earth's largest impact event on record, but scientists have yet to locate its crater.

Some believe the blast was caused by a mid-air explosion. Others think it was caused by hard impact. In 2012, an Italian research team found evidence that pointed to a small 500m crater in Lake Cheko as the point of impact. The study was hotly contested because that crater is located some eight kilometres from the Tunguska event's supposed epicenter.

The Italian group collected seismic measurements of the crater's bottom, which showed about 100 years' worth of accumulated sediment. And Lake Cheko's bed — which is shaped like a crater — was deeper than is typical for the region. Dense stony substrate beneath the sediment was likely the remains of the exploded meteoroid, they concluded.

In 2017, a Russian team contested those findings. Core samples drawn by the Russians seemed to indicate that the lake bed was nearly 200 years older than the Tunguska event. Geologically young, but not young enough to be the epicenter.

Tunguska research expedition, 2022

Lake Cheko bottoms out at 54m and resides in the Tungussky Nature Reserve, a rural stretch in central Siberia's Krasnoyarsk region. This winter expedition will start a cycle of long-term research there.

"The team of researchers aim to study how thick the lake bottom’s sediments are, and take primary samples," reserve inspector Evgenia Karnoukhova told The Siberian Times. "The data they’ll gather will be analyzed and passed on to geologists. We are not speaking about the search for any celestial body at this stage."

Emmeline Freda Du Faur defied convention by pioneering women's climbing in New Zealand. But her sexuality and tragic suicide long overshadowed her achievements. Eventually, the first woman to climb Aoraki/Mount Cook had a memorial stone placed upon her previously unmarked grave.

Early life

Born in 1882 in Sydney, Australia, Du Faur’s childhood involved long days exploring Ku-ring-gai Chase National Park. Near her family home, the sprawling 150 sq km park was a welcome release for the highly strung Du Faur to explore pursuits atypical of women at the time. Instead of completing her nursing studies, she taught herself to rock climb. Rather than play with girls her age, she roamed with her dog.

For her summer holidays, Du Faur traveled to New Zealand with her family. During one holiday, she saw photographs of Aoraki/Mount Cook, New Zealand's highest peak. These photos inspired Du Faur.

In 1906, she took her first trip to the Hermitage Hotel. Nestled within Mount Cook National Park, at the foot of the Mueller Glacier, the Hermitage Hotel dates back to 1884. When Du Faur arrived, the snowy mountains captivated her. From the hotel windows, she gazed out at Aoraki/Mount Cook and determined to reach the summit.

Alpine climbing

On another trip to the Hermitage Hotel in 1908, Du Faur was introduced to Peter Graham. Graham, a pioneering guide in the area, had conducted expeditions up Fox Glacier and made 13 ascents of Aoraki/Mount Cook. He was perfectly positioned to introduce Du Faur to alpine climbing.

More than just a keen student, Du Faur was determined, strong, and capable. First, Graham tested her ability with a 10-hour traverse of Mount Wakefield and Mount Kinsey, at the southern end of the range. He quickly recognized Du Faur's competence. Building on her rock-climbing experience, he added ropework and snow and ice climbing to their sessions.

Beneath her bravado, Du Faur struggled with her sexuality in an uncompromising society. Homosexuality was illegal in the early 1900s, and society saw lesbianism as a psychological disorder. Climbing gave Du Faur an escape.

In 1909, with Graham guiding, Du Faur achieved her first significant ascent, 2,627m Mount Sealy. Despite the pair’s climbing competence, social customs dictated that an unmarried woman should not camp alone overnight with a male guide. They were forced to invite a chaperone to join them.

Two days later, Du Faur ascended The Nun’s Veil (2,736m). Within a week, she completed the first female ascent of the west ridge of Mount Malte Brun, crossing the famous Cheval ridge to the summit with Graham and another client.

Fighting convention

It wasn’t just sleeping arrangements that Du Faur had to worry about. The public also scrutinized her attire. Du Faur dressed in a skirt to just below the knee, knickerbockers, and long puttee leg-wraps to cover her ankles. She wore this on all her climbs, despite sunburn, discomfort, and the safety hazards that came with climbing in a cumbersome skirt.

In climbing, Du Faur had found her calling. After her successful first season, she returned to Sydney and embarked on three months of training at the Dupain Institute of Physical Education. This was important for two reasons. Muriel Cadogan trained her and became her romantic partner, and her training prepared her for a return to New Zealand, setting up her pioneering Aoraki/Mount Cook ascent.

In late 1910, Du Faur sailed back to New Zealand from Sydney and enlisted Graham once again. They had previously attempted Aoraki/Mount Cook via Earle's Route but a bergschrund defeated them. This time, Du Faur was certain that her extra training would ensure a successful summit.

They warmed up with climbs of Mount Annette and Mount Mabel. Then they knocked off a virgin 2,438m peak near Barron’s Saddle, at the head of the Mueller Glacier. Next, with the extra support of Graham’s brother Alec, they set off for Earle's Route on Aoraki/Mount Cook.

Aoraki/Mount Cook

This time, not only did they reach the summit, but theirs was only the second ascent of the west ridge. They completed the climb in record time, just six hours. Du Faur was now both the first woman to reach the summit and the first Australian.

In sharing her tent with her male guides this time, Du Faur also broke with needless tradition. “I was the first unmarried woman…to climb in New Zealand, and in consequence, I received all the hard knocks, until one day when I awoke more or less famous in the mountaineering world, after which I could and did do exactly as seemed to me best,” wrote Du Faur afterward.

Unstoppable, that same season she climbed Mount De la Beche (2,979m) and Mount Green (2,828m). Then, she became the first person to climb Mount Chudleigh (2,944m).

In the next two seasons, Du Faur scaled the virgin peak now named Mount Du Faur (2,389m) and made the first ascents of Mount Nazomi (2,953m), Mount Dampier (3,420m), Mount Pibrac (2,567m), and Mount Cadogan (2,398m). She also made second ascents of Mount Tasman (3,497m) and Mount Lendenfeld (3,192m).

But her most notable climb was a grand traverse with Peter Graham and David Thomson. The trio traversed all three peaks of Aoraki/Mount Cook in 1913. The traverse is now regarded as one of the classic climbs of New Zealand's Southern Alps.

Her final season

This would be Du Faur’s final climbing season. Cadogan (who had been a respected feminist in Sydney) had unwittingly cast their relationship into the spotlight. In 1914, the couple relocated to England. They intended to climb mountains in the European Alps, Canada, and the Himalaya.

In 1915, Du Faur published The Conquest of Mount Cook. It has proven vital for preserving her legacy.

World War I prevented the couple from ever achieving their climbing plans abroad. Over the next few years, their relatively contented life began to unwind. The government sent them to mental institutions and forcibly split the couple up because of their sexuality. In 1929, Cadogan committed suicide.

Du Faur returned to Sydney. But without Cadogan, she fell into depression. In 1935, she fatally poisoned herself with carbon monoxide.

An unmarked grave

Shunned by society, regardless of her contribution to mountaineering, Du Faur was not given a formal burial. Instead, she was buried in an unmarked grave.

Her private life with Cadogan rendered her seemingly forgotten until Sally Irwin released a biography in 2000: Between Heaven and Earth: The Life of Mountaineer Freda du Faur: 1882–1935.

New Zealand farmer Ashley Gaulter read a copy of Irwin's book and decided to put right Du Faur's final resting place.

“I read that she was over here in Manly Cemetery, and at the time, I was living quite close by, and I thought, well, I’ll go and find her,” Gaulter said.

“I couldn't find her in the first instant, and then found a map and tracked her down. I found this poor little patch of grass surrounded by other tombstones and there she lay in an unmarked grave. And that seemed like an injustice,” he said.

Gaulter enlisted the help of a local stonemason to make a gravestone. Finally, Du Faur has a marked gravesite in Manly Cemetery, Australia.

Hans Henrik was an unusual polar explorer. He went on five dramatic arctic expeditions and saved the lives of many of polar explorers, but he was always homesick.

Henrik was a family guy who loved his kids and wife so much that he refused to go on expeditions without them. So they accompanied him. His youngest son, Charlie Polaris, was born on board Charles Francis Hall's ship, the Polaris, just before it ran aground. The newborn baby then participated in a 2,900km, six-month drift on a disintegrating ice floe.

Geese were the messengers

Two months ago in our present era, in Qeqertarsuaq on Disko Island, we were following a flock of Canada geese for no apparent reason. The geese were not supposed to be here at this time of the year. By mid-September, they should have all been en route to Canada. But this summer was eternal, and here they were, devouring the late blueberries and getting fatter. Instead of flying away, they were leading us somewhere.

They took us to the local cemetery, to some old graves. There were no berries here. They walked across old stones and suddenly took off. Making a circle above our heads, they then vanished, leaving us alone at the old grave.

That was a sign. Geese were the messengers, as they say in Greenland. The geese brought us to Suersaq, a.k.a. Hans Henrik, the great Inuit polar explorer.

Two islands have been named after Hans Henrik, and a stamp in Greenland honors his memory. But his posters do not adorn the walls of aspiring polar explorers, and his Inughuit name, Suersaq, is known only to aficionados.

Some say that Suersaq did not take Arctic expeditions seriously, that he saw the efforts to map the Arctic as a substitution for a big polar bear hunt. Indeed, Suersaq had no ambitions to be “the first” in the race to the North Pole. Like Ootaah and other Inuit explorers, he did not join these extreme expeditions with endurance records in mind. It was life as usual, though his employers called it "an expedition".

But it was his practical skills, endless adaptability, and unbreakable spirit that helped save qualified Europeans and Americans. They came to the Arctic with a mission but instead went into survival mode when Sila, the weather, had a final say.

A life of freedom

Suersaq never thought of himself as a pioneer or a hero. He did not attribute what he did daily to courage or endurance. Instead, he was vulnerable and emotional, he felt threatened among foreigners, but he was who he was.

He deserted the first expedition he took part in because that life got too boring. Instead, he fled with his fellow Inughuit to live an unstructured life. The Inughuit were free, while the expeditioners were not.

During his flight, he hunted polar bears and found a girl, Mequ, the love of his life. That was much more fun than establishing some official and -- from his point of view -- irrelevant record, like reaching the 82nd parallel by dogsled. Besides, he knew that his Inughuit buddies had trod this ground previously on many hunts and none of them saw it as a special accomplishment.

First Inuit man to write a book of exploration

Yet Suersaq was an educated man. He wrote a book about his arctic adventures, the first Inuk to have done so. Originally composed in 1877, it has often been reprinted. Memoirs of Hans Hendrik, The Arctic Traveler gives details of the Kane, Hayes, Hall, and Nares expeditions, as well as an account of August Sonntag's death. Suersaq wrote it in Kalaalissut, the Greenland language, and Hinrich Rink, the colonial director for Greenland, translated it into Danish and English and published it.

Born in the southern settlement of Fiskenæsset (today Qeqetarsuatsiaat), some 100km south of Godthåb (today Nuuk), as Hans Hendrik, Suersaq was raised in the Moravian faith and attended a Moravian school, where he learned to write and read.

His first expedition

At age 18, Suersaq was already an excellent subsistence hunter and great kayaker. Not surprisingly, the American explorer Elisha Kent Kane recruited him. Kane was commander of the Second Grinnell Expedition, bound for the island’s northern end to search for John Franklin's lost expedition.

Examining the fate of past American misadventures in Northwest Greenland, Kane knew that the only way to survive in these latitudes was to live Inuit-style. He was looking for someone who could be a perfect Inuit: a dogsled driver, a kayaker, a hunter, and an interpreter.

Kane says of Suersaq: "I obtained an Eskimo hunter at Fiskernaes, one Hans Christian (known elsewhere as Hans Hendrik), a boy of eighteen, an expert with the kayak and javelin. After Hans had given me a touch of his quality by spearing a bird on the wing, I engaged him."

Suersaq accepted the offer since he had to help his elderly parents.

After a rapid start, the expedition got stuck near Cape Alexander, in the Thule District, for two long winters. It was in the winter of 1854 when Suersaq became famous and a much-desired guide among American explorers. When four men disappeared on the ice, he found their sled track and brought a rescue party to the frozen men. When expedition members started to starve and developed scurvy, he was able to get food. Once again, he had saved the party.

Free spirit

Suersaq was skillful but he was a free spirit. The expedition routine was too boring for him. He was also frightened by the white men, whom he thought were going to harm him. Something might have been lost in translation, but this is how he felt according to his book. So when he met the local Inughuit of far northern Greenland (a different culture than the more southerly one he came from), he fell in love with their lifestyle. They were truly independent. The Americans were not. So he left with the Inughuit.

It was a brave move. At that time, the West Greenlanders saw these northern denizens as dangerous outcasts. There were superstitions, but Suersaq managed to overcome them. Yet as a devoted Christian, he worried for the Inughuits' souls.

A time of gifts

Suersaq received two very important gifts during his escapade. First was the beautiful Mequ, who became his wife and had four children with him. The second was his name, Suersaq. According to Nuka Muller, one of the most prominent Eskimologists of our time, Suersaq is an Inughuit name that means “the saved" or "the healed one”. It was bestowed only by Inughuit angaqqoks (shamans), which for us means this: Hans Henrik had to work hard to deserve it.

Despite his desertion, Kane so highly valued Suersaq that he named an island north of Etah after him.

When a member of Kane’s expedition, Isaac Israel Hayes, started a new expedition toward the North Pole in 1860, he invited Suersaq to join him. Suersaq agreed under one condition: He would not leave without his wife and son. This was not an easy decision for Hayes, but he agreed to let them join the expedition.

Suersaq provided food and shelter for Hayes and his men, while Mequ fished, cooked, sewed, and kept the seal-oil lamp burning. She turned out to be a valuable addition to the expedition too, and the couple’s fame increased.

Hayes' expedition failed to reach the North Pole. It also lost a man, the second in the command, a German astronomer August Sonntag. Sonntag fell through the ice during a sledge journey with Hans. Though Suersaq saved Sonntag from the freezing water, almost dying himself, he could not save his life. Sonntag died during the night from hypothermia. Suersaq was on the verge of death too, but he managed to reach the Etah Inughuit and find refuge.

The arrival of the Polaris

After the departure of Hayes, Suersaq spent 10 years in Upernavik working for the Royal Greenland Trade Company. Then one day, another ship with a mission to discover the North Pole arrived. This time it was Charlie Francis Hall, the leader of USS Polaris, who asked Suersaq to join his expedition. Suersaq had the same answer as before: He would not travel without Mequ and the kids. This time, there were three of them. Hall accepted.

The Polaris managed to go further than any ship before her, but then, in the northern part of Nares Strait, Hall suddenly fell ill. He died in Thank God Harbor two weeks later, apparently from poisoning. Shortly before his death, Hall named another island after Suersaq. This time it was Turtupaluk, which means a “kidney” because it looks like a kidney, a rocky island in Nares Strait. Hall named it Hans Island.

A barren, steep-sided, one-kilometre-wide bit of land, Hans Island has become modestly famous in recent years, because both Canada and Denmark claim ownership of it.

Six months on an ice floe

After losing their leader, the Polaris eventually turned south. One night in October, she became trapped in the ice in Smith Sound. Fearful that the pack ice would crush her, the crew prepared to abandon ship. Fourteen people stayed on the Polaris, but 19 off-loaded supplies and found refuge on an ice floe. Thus started a six-month drift, one of the most dramatic survival stories in the history of arctic exploration.

Suersaq, Mequ, their children, and two other Inuit from Canada, Ipirvik and Taquilittuq, also with a baby, took care of the American, German, Danish, and Swedish explorers. They built three igloos, and Hans was able to hunt seals. The Inuit families cooked on the seal-oil lamp, to save fuel. The Europeans did not like the smell and used one of their two remaining boats as fuel instead. The clash of cultures was obvious.

When the dogs got into the storage and ate much of the provisions, the Europeans shot five dogs on the spot. They looked on in disgust when the Inuit made a feast from the killed dogs, not wanting to waste the meat. Little did they know that in about two months they would be happy with the dog meat. By then, the crew would have to live off boiled dried seal skins, which were almost impossible to chew. If they were lucky, they'd get some seal entrails and frozen blubber.

In March, after reaching Nares Strait, the ice floe started to disintegrate. Suersaq was helping people to switch between the boat, which was too small to hold everyone (remember, the second boat was burnt), and the small ice floes. He did this 24/7 until the last day of April when the castaways spotted a ship.

They fired guns, jumped, and shouted. But it was all in vain, they were too far away to be noticed. Suersaq jumped into his skin kayak and rushed to the sealing ship. Once again, he was a savior.

Thirty years of adventure

Two years passed and another expedition, this time the British Arctic Expedition led by commander George Nares, recruited Suersaq. Again, Suersaq agreed.

This time, he left his family behind. It was a mistake. He felt lonely, missed his family, did not trust foreigners, and was soon thinking of escape. He was relieved when he finally returned home.

In 1883, 30 years after he joined his first arctic Expedition, a Swedish expedition to Cape York recruited Suersaq for one last season. He joined only for the summer. He knew that his time in the adventure world was over.

Suersaq died in 1889 at the age of 57 and was buried in the cemetery above Qeqertarsuaq.

Gone but not forgotten

We found some of his old photos and the first edition of his book in the Museum of Qeqertarsuaq, but we made our best discovery in the community house. We gathered there for an evening concert. The leader of the Inuit theatre troupe from Nuuk was our friend, a young talented actor and designer born in Qeqertarsuaq. His name is Hans Henrik Suersaq Poulsen. He is Suersaq’s direct descendant.

Suersaq Junior performed a play about his great-grandfather. This is what he says: “We have heard so much of the qallunaat (white) explorers like Knud Rasmussen and Robert Peary, and so little about the Greenlanders who ensured that these expeditions were a success. We wanted to tell their part of the story. And naturally, Suersaq was to be a part of the show because he was the first Greenlander to be a part of a big expedition.”

While Suersaq Sr. explored the High Arctic, Suersaq Jr. explored a place between tradition and modernity.

The lesson of Suersaq

In recent months, my partner Ole Jorgen Hammeken and I were asked to teach young Inuit children some survival skills. We gave practical classes to children in Qeqeratarsuaq and Ilulissat. We decided to base our classes on Suersaq’s drift.

At first, we started our drift on one oversized sheet. At the start, it could fit a tent and 20 people. As the game progressed, we folded the sheet, making it smaller and smaller. Finally, it was able to fit only four people. The greatest surprise was that the children found ways to continue the drift, very similar to Suersaq’s methods.

Those born in the Arctic are prepared for abrupt change. It is your everyday life, life as usual. It is really easy to brainstorm with the Inuit children who literally live on the ice. And now, their real-world knowledge is backed up with academic knowledge. These children, many of whom are young dogsledders, young scientists, and artists as well, will lead the world in future arctic exploration.

Baintha Brakk I (7,285m), better known as Ogre I, has been attempted over 20 times. Only three expeditions have summited. ExplorersWeb dives into the history of this imposing granite tower.

The Karakoram presents some of the toughest mountaineering challenges on earth. Angular mountains, gigantic towers, dizzying ridges, unknown faces in remote places. It has always attracted the best climbers. Today, more than the 8,000'ers, it is the Karakoram's 7,000m and 6,000m peaks that are the future of mountaineering. Here, exploration continues to play the most important role.

Panmah Muztagh is a sub-mountain range in the heart of the Karakoram. In the Baltistan district of Pakistan, it is made of four groups of mountains -- the Ogre group, the Latok group, the Choktoi group, and the Chiring group.

The Ogre

Baintha Brakk I (7,285m) is better known as Ogre I. Besides its main summit, it has two secondary peaks. Its west and east summits are both 7,150m. Like a violin standing upright, this steep granite tower, with a prominence of more than 1,800m, requires serious commitment.

Over 20 expeditions have tried to climb it, but only three have managed to reach the summit.

The commitment begins at its often storm-battered Base Camp. From there, whichever route climbers choose hides danger. The weather is harsh and unpredictable, and the peak itself grants no respite. Once embarked on the ascent, the climber has to endure lack of oxygen, the endless lengths of its pillars, the challenging faces, the hanging seracs, and always, the ferocious winds.

The normal routes on 8,000m peaks have higher mortality rates, but then, far fewer people attempt the Ogre. There are no high-altitude tourists, you don't pose for photos, you can't get a helicopter directly to Camp 2, and there's no one waiting for you with hot tea at the camps.

The first ascent

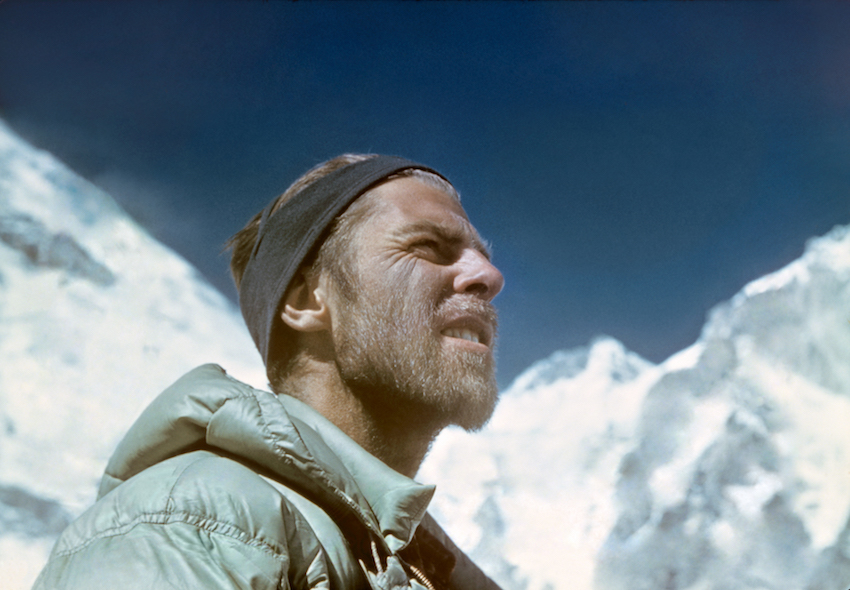

After three previous attempts, the main summit of the Ogre was climbed for the first time on July 13, 1977. British climbers Doug Scott and Chris Bonington ascended via the southwest spur to the west ridge, and over the west summit to the main summit. They made a quick push, 15 straight hours of climbing from their final camp. The last section of the climb was a tower with a 100m vertical face.

After reaching the summit, disaster struck. At 7,200m, at the start of the first rappel, Scott fell. The rope held, but Scott hit the rockface hard. He lost his goggles and ice ax and broke both legs. Bonington climbed down to him, and they spent the night in a bivouac on a ledge.

”It was a long night waiting for the first light of dawn, which was ages coming,” Scott recalled in his book, The Ogre. "There was no wind, no sound at all, just a penetrating cold kept at bay by involuntary shivering and creating friction heat by rubbing arms and legs."

It was a slow and technical descent, hanging from ropes and crawling in sections. Scott dragged his broken legs inch by inch down the Orge. Their companions, who were in Camp 2, gave them up for dead and began to descend.

A storm forced Scott and Bonington to shelter for two days in a snow cave. Bonington contracted pneumonia, so he too was very weak. Things got worse when Bonington fell on his side and broke two ribs. Despite everything, they continued to descend, helping each other with all their might.

Finally, they met their two companions, Mo Anthoine and Clive Rowland. Together, they were able to reach Base Camp after a week. There, they had to wait a long time for rescue. Somehow, everyone got out alive.

The second ascent

On July 21, 2001, Urs Stocker, Iwan Wolf, and Thomas Huber reached the summit via the south pillar. Bad weather forced them to take refuge in a crevasse at 5,000m. At first, they had a dispute with an American team that was on the same route and had to wait for them to withdraw.

They built Camp 1 at 5,000m and then slept in two porta-ledges fixed in the middle of the pillar, at 5,900m and 6,200m. The team made a final camp at 6,500m at the foot of the traverse to the main summit, which was 800m of mixed terrain. From there, they began their summit push on July 21.

The wind was very strong, but they were able to top out. The group also made the first ascent of the Ogre III.

The third ascent

Hayden Kennedy, Kyle Dempster, and Josh Wharton started up the southeast ridge, then moved up the southeast face, and finally a section of the south face.

The team had to struggle through a rubble traverse and climb on mixed terrain. They bivouacked at 6,900m. Wharton got sick, but Kennedy and Dempster continued to the main summit. On August 21, 2012, they topped out. The descent was very difficult because Wharton was still unwell.

In the same season, Kennedy and Dempster made the first ascent of the east face of K7 (6,934m).

"I think alpine climbing comes down to 40 percent luck, 40 percent motivation, and 20 percent skill," Kennedy said after the expedition. "You have to be really motivated to do that. You just keep building and dealing with the bad rock and dealing with whatever."

For this climb, the young climbers received the Piolet D' Or.

Unfortunately, Dempster and Kennedy both died a few years later, Dempster on Ogre II in 2016, and Kennedy in 2017 in Montana. One day after his girlfriend died in an avalanche, Kennedy committed suicide. They were two unique talents.

Notable attempts

On June 15, 1983, French climbers Michel Fauquet and Vincent Fine completed 900m of the vertical south pillar without a fixed rope. They still had over 600m remaining to the summit, 400m of snow slopes, and more than 200m of rock. However, the weather turned and they had to wait in their bivouac tent.

On June 17, they tried to continue. They reached 7,100m before they decided to descend. They were very close, but the Ogre was not accommodating.

The south buttress

On August 5, 1993, a Swiss-German team led by Tom Dauer arrived at Base Camp. After two weeks of miserable weather, they fixed rope on the buttress up to 6,100m. They wanted to continue up the alpine-style route in two teams of three each. They made two attempts, but bad weather forced them to abort.

When the weather cleared on August 28, they tried again. The next day, Phillip Groebke fell while jumaring and died immediately. Nobody witnessed his fall to explain what went wrong. The group then retreated from the mountain.

The southwest face

In 2002, a Japanese team attempted the southwest face. Japanese climbers are famous for attempting new routes, and the Ogre has many potential new lines. But the southwest face is very dangerous because of a large number of seracs. The Japanese team almost made it but had to turn around 10 to 15 metres before the summit.

Some climbers might claim a summit, but the Japanese climbers were clear: They did not summit the Ogre, even if they only missed by a few metres. Their honesty is commendable.

The southeast buttress

On July 12, 1993, Americans Tom McMillan, Peter Cercelius, and Carlos Buhler made Base Camp at 4,450m. They intended to start their route from the head of the Choktoi Glacier. A group of Japanese climbers was already working on the route through the icefall, but the seracs changed day by day. The Americans did not want to enter the icefall and decided to flank it on ice slopes and rock walls.

The ascent to the col was steep, with 12 pitches of mixed ice and rock climbing. The Japanese, who had already roped off this dangerous stretch, offered to share the route and the ropes. They were about to withdraw after 20 days of trying. Only seven of those days had provided good weather. The Japanese fixed six pitches on ice. They also left one pitch equipped on the 600m granite buttress.

The U.S. group advanced, but the weather deteriorated and they had to return to Base Camp. McMillan got sick. On August 30, after several attempts, Buhler and Cercelius began their push up the buttress. But with only three or four pitches left, they saw that they could not continue alpine style and so withdrew.

The north face reconnaissance

Herve Barmasse and Daniele Bernasconi reached the foot of the north face of the Ogre at the beginning of July 2012. The north face is also dangerous, but Barmasse felt they had a chance. "There are weak points if you accept the constant exposure to avalanches and icefall," he said.

They started to acclimatize. After nine days at or above Base Camp, they wanted to start the climb. However, July 12 to July 28 yielded only two days of fine weather. Instead, they went to other peaks and returned to the Ogre on July 28. When they returned, they saw that even the vertical rock walls were covered in snow.

The north face of the Ogre remains one of the greatest unsolved challenges in the Karakoram.

The next time you hear the high-pitched whine of a drone cut the alpine silence, it may not be because an influencer is hunting down video content.

In Scotland, mountain rescue teams have implemented drones to make their jobs, and the mountains at large, safer. The machines can already help search for missing or injured people in remote, hard-to-access locations. Drone experts see their mountain utility expanding, thanks to the wide range of tools and technology they can carry.

ExplorersWeb has called drones "game changers" for mountain rescue. In those applications, they work fairly intuitively. Most elementarily, a drone pilot on the ground can help rescuers suss out the situation from below with the unit's onboard camera. Operators can also fit drones with various gadgets like lights, speakers, and even radio handsets.

Experts say the technology has helped rescue teams access terrain previously thought too dangerous for ingress. So far, Scotland's 28 volunteer search-and-rescue teams have all adopted the technology. Rescuers implemented drones on Ben Nevis, the southern uplands, Fife, and the Trossachs over the last year.

Drones in mountain rescue: how it works

John Stevenson leads a rescue team for Lochaber mountain rescue in Fort William, which covers Ben Nevis. The group currently employs four drones. Their most critical advantage is in scouting.

"The drones are definitely an asset; there's no doubt about it," Stevenson told The Guardian. "We're putting drones into places where years ago, we might have thought twice about putting people in."

The Lochaber unit has also found that drones can sweep terrain faster than humans can during searches for missing persons. Tom Nash, a former RAF Tornado navigator, founded the Search and Rescue Aerial Association of Scotland and has trained rescuers to pilot drones across the country. He explained further:

Risk reduction is a key use of a drone. Previously, where someone has needed to do a rope rescue or a stretcher lift, you would have some poor person dangling over the edge of a cliff, roped back, peering over saying 'I think we should put the rope down here.' Now, just put the drone 20 yards out the other side of the cliff and look back, [and] you can see where the casualty is. You can floodlight that at night. We can put a speaker on, and if we know it's going to be a while, we can speak to the casualty and say help is on the way, 'give us a thumbs up if you're OK but can't move.' That's a really critical use.

Nash looks for drones' roles on rescue crews to keep expanding as pilots' skills and available technology advance. In the future, he said they could potentially "drape" 4G mobile phone coverage over areas where phone masts are knocked out or don't exist. Eventually, drones could even deliver supplies and equipment to rescue sites.

"It's so exciting because it can and will revolutionize things," he said.

Kongur Tagh (7,719m) lies in the Kashgar Mountains, near the eastern edge of the Pamirs. It is in one of the most remote areas of China, within the Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region.

In 1981, a team of talented British climbers took it on alpine style. But Joe Tasker, Pete Boardman, Alan Rouse, and Chris Bonington weren't the only group on the mountain.

Little-known giants

Although not far from the ancient Silk Road, the Kashgar mountains remained largely unknown to Westerners until the late 19th century. Some colossal peaks in the area include Kokodag (7,210m), Kongur Jiubie (7,530m), Jungmanjar (7,229m), Karayalak (7,245m), and the almost 8,000m Kongur Tagh.

Early explorers

At the end of the 19th century, some western explorers first probed the area. In 1868, Englishman George Jonas Whitaker Hayward sketched a big peak onto the map to the south of Kashgar. Then in 1895, English explorer, geographer, and diplomat Ney Elias crossed the Karatash Pass from the Taklamakan desert. He was the first European to reach Karakol Lake, very close to Kongur Tagh.

Kongur Tagh was unknown in Europe until 1900 when Hungarian geographer Aurel Stein brought home the first good photographs of the range, taken from Karakol Lake.

New mountains opened for climbing

In the late 1970s, China opened eight mountains for climbing. Among them was Kongur Tagh, the highest peak in the Pamirs, and still unclimbed.

In 1980, Michael Ward, Chris Bonington, and Alan Rouse, along with some scientists, made a reconnaissance trip to Kongur Tagh. They did not have much information about it. The most recent information available was an article written by Sir Clarmont Skrine, Consul General in Kashgar between 1922 and 1924, almost 60 years earlier. The Chinese, who had climbed nearby Kongur Jiubie, could share very little about Kongur Tagh. It was always hidden behind the other peaks.

The Chinese explained that they had not climbed the mountain because it was too enigmatic, with ever-changing weather. On this first trip, Ward and his team explored the area and planned a route for the following year.

Friendly competition

While the British climbers began to organize their 1981 expedition, a Japanese group also wanted to climb Kongur Tagh, from the north side.

At the end of May 1981, the British climbers, some scientists, and a cameraman arrived. The four climbers were a magical quartet: Joe Tasker, Pete Boardman, Alan Rouse, and Chris Bonington. All remarkably talented mountaineers.

The Brits put up Base Camp near one of the glaciers, then established an Advanced Base Camp near Koksel Pass, situated on the Kongur-Muztag ridge to the south from Karayalak Peak.

The first summit push

On June 23, they began their first summit attempt from the south side of Karayalak Peak. Bonington planned to climb the southe ridge of Junction Peak (7,350m), traverse it, and then climb the pyramid that led to the summit of Kongur Tagh via a plateau.

However, four days later, they faced a major dilemma. The team ran out of fuel and was low on food. They weren't far from the summit, but Bonington felt they shouldn't risk it. The distance was tricky to estimate, and the terrain was totally unfamiliar.

There was a discussion. Alan Rouse and Joe Tasker did not want to enter the debate, although they considered Bonington to be right.

Boardman took the opposite view. He wanted to continue. This was partly because Boardman had more fuel left, while Bonington had used more than he should have.

A heated discussion followed, but eventually, the group decided to withdraw to Base Camp, and tempers died down.

The second push

Time was against them. The British longed for the summit of this huge hidden mountain, but the Japanese team was already in the area. The Japanese only had permission to reach the Kongur Tagh Base Camp beginning July 14, but they had already climbed Muztagh Ata to acclimatize. Now, they were on their way to the north side of Kongur Tagh.

Bonington's team knew that the weather was unpredictable and the final pyramid of the peak was very difficult. “The weather dominated everything we did," Bonington later recalled. "Kongur seemed to produce its own brand [of weather], the clouds sitting on it like a cap and enveloping the whole massif.

On July 4, the group left Base Camp again. They would try a new route via the southwest rib and Kongur Col. By July 7, they were at the foot of the western Kongur mountain range. Then bad weather swept in, and the four climbers had to hide in crevasses on the west ridge at 7,340m. In his book Kongur: China's Elusive Summit, Bonington called these crevasses "snow coffins."

The final pyramid was like the Eiger. They could barely advance because of fatigue, the terrain, and strong winds. Finally, on July 12, they reached the summit. After a difficult descent, they made it safely back to Base Camp.

Bad luck on the north ridge

The Japanese expedition was not so lucky. They separated into two groups, to attempt the north side from different Base Camps. One of the groups, a three-man team, chose to climb the north ridge alpine style.

On July 16, Yoji Teranishi, Mitsunori Shigi, and Shine Matsumi left Base Camp with food for nine days. They were last seen on July 23, at 6,500m. The weather deteriorated until August 3. When it finally improved, there was no sign of the climbers. Bonington suggests that after reaching the summit, they were probably swept away by an avalanche during the descent.

Kongur Tagh's first ascent was a major achievement and brought together some of the greatest climbing talents of the time. Sadly, Boardman and Tasker died 10 months later on the northeast ridge of Everest, and Alan Rouse passed away on K2 in 1986.

BY MARTIN WALSH, ANGELA BENAVIDES, ASH ROUTEN, KRIS ANNAPURNA, REBECCA MCPHEE, SAM ANDERSON, BRYON DORR, SEIJI ISHII, GALYA MORRELL, JERRY KOBALENKO

In this, the longest piece ever published on ExplorersWeb, we profile -- in no particular order -- the 100 figures who have most influenced adventure in the last century.

Some achieved their standing from one visionary accomplishment, others from an exceptional body of work. There are kayakers, polar travelers, mountaineers, ocean rowers, cavers, astronauts, archaeologists, aviators, and more.

You may find some of your personal favorites missing from this list. In some cases, this may have been simply an oversight. In others, we deemed that certain obscure figures had contributed more than others who were perhaps more famous.

All 100 have pushed the limits of their chosen fields, set a standard of excellence, and made the world better known.

1. Knud Rasmussen

Speciality: Arctic Exploration, Anthropology

Best known for: The Thule expeditions

Knud Rasmussen is a throwback to the wild days of exploration, when hardy fellows went on adventures to learn about the blank spots on the map and the people who inhabited them. This is probably why Rasmussen won't feature on many lists of explorers, as his legacy is one of knowledge over athletic achievement.

Son of a missionary, Rasmussen spent his early years in Greenland immersing himself in the local language, driving dog sleds, hunting, and picking up the dark arts of travel in the cold. Following some early expeditions at the turn of the 20th century, Rasmussen cemented his place in history with The Thule Expeditions, a series of polar exploration and ethnographic expeditions from 1912-1933. Most focused on Greenland, but the fifth and perhaps greatest of the Thule expeditions covered nearly 20,000 miles between Greenland and Siberia, including the first European dogsled journey across the Northwest Passage.

For this and his resulting ethnographic works, Rasmussen has been dubbed the "Father of Eskimology." Although never formally educated, Rasmussen's contribution to anthropology, polar exploration, and knowledge of the native people of the Arctic is recognized globally.

2. Thor Heyerdahl

Specialty: Ocean expeditions

Best known for: Crossing the Pacific Ocean on a raft

In 1947, Thor Heyerdahl and a small crew spent three-and-a-half months traveling across the Pacific Ocean. What makes this journey stand out is they did it on a raft. Heyerdahl was fascinated by how Pacific inhabitants had reached the remote Pacific islands. To test a theory (since discredited) that they came from South America, he built the Kon-Tiki, a balsa raft from natural Peruvian materials. They sailed from Peru to Polynesia to prove it was possible.

He carried out two further expeditions, this time opting for reed boats. The first was a crossing of the Atlantic Ocean, from Morocco to Central America. Again, this was to prove a theory, that the Egyptians might have influenced pre-Columbian cultures.

Next was a 4,000km voyage down the Tigris River and the Persian Gulf, across the Arabian Sea and into the Red Sea. It took four months. This time he wanted to establish the possibility that ancient Sumerians may have used similar methods to spread their culture.

3. Jerzy Kukuczka

Specialty: High-altitude climbing

Best known for: New routes and first winter ascents on 8,000'ers, second to complete all 14 of them, and fastest to climb them before the age of fixed ropes

The Polish trailblazer, lord of winter, Jerzy Kukuczka, climbed all the 14 8000'ers in seven years, 11 months, and 14 days. He held the record for 27 years.

Kukuczka was one of the Polish Ice Warriors. He climbed four of his 14 8,000'ers in winter. Three of them were first winter ascents, and he completed two of them in one season. Likewise, he summited 10 of his 14 8,000'ers via a new route, a record that remains unbroken.

While many remember the race between Kukuczka and Messner to bag all 14 8000'ers, both climbers pursued excellence on each climb, rather than mere speed. While Messner had a more individual approach to expedition planning, Kukuczka was a team player. But even as a member of large Polish expeditions, he left his imprint. He forged on when others turned back. He achieved nearly all his 8,000m summits on the first attempt, without the luxury of broken trails, fixed ropes, and well-equipped camps. Kukuczca was simply not interested in routes climbed previously by others, or in "playing for low stakes." He only used oxygen on the highest section of the new Polish route on Everest.

Kukuczka has a long list of accomplishments. He soloed Makalu in alpine style via a new route in 1981. Together with Tadeusz Piotrowski, he opened a new route alpine style on K2, which has yet to be repeated. Also, he blazed new routes on Gasherbrum I, Gasherbrum II, Broad Peak, Manaslu, Shishapangma, and Annapurna. He climbed Nanga Parbat via the previously unclimbed SE Pillar and Everest's South Pillar.

Kukuczka died while climbing the mightly South Face of Lhotse. Leading a pitch at 8,200m, with a 2,000m drop below his feet, he fell. The second-hand rope he had bought at a market in Kathmandu snapped.

In the 21st century, Kukuczka's records may be beaten on paper, but they won't be equaled because the world has changed. While the mountains remain, technology, logistics, and climbing style have changed the game.

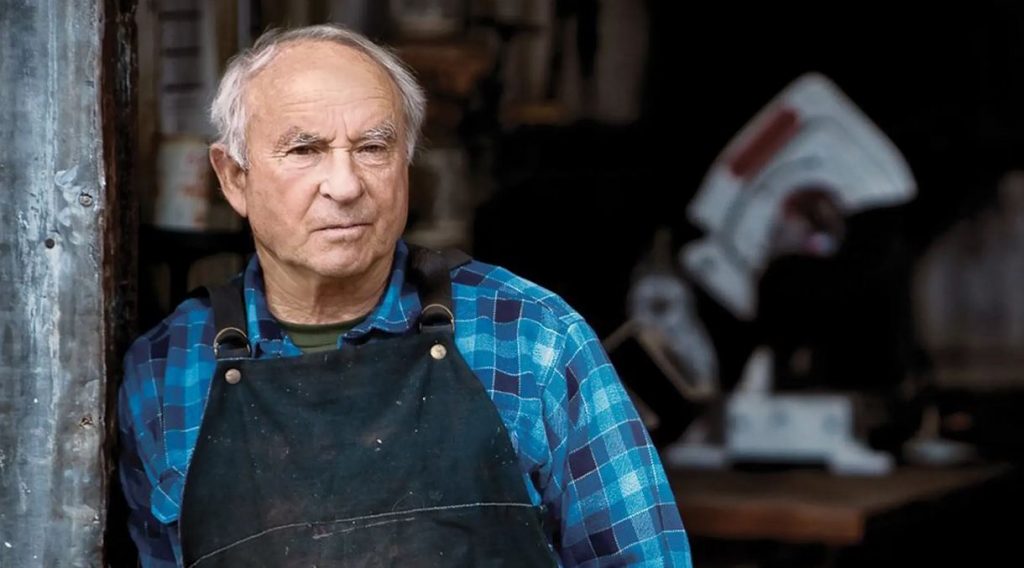

4. Reinhold Messner

Specialty: Alpinism, High-altitude climbing

Best known for: First to climb all 14 8,000'ers and climbing them without supplementary oxygen

High-altitude mountaineering's most famous name for the last 50 years, Messner remains a strong voice in the mountaineering community at age 77. Born in South Tyrol (northern Italy but German-speaking), he broke boundaries on the Himalayan giants. In 1978 with Peter Habeler, he made the first ascent of Everest without supplementary O2. At the time, it was considered "impossible" for a human to survive at Everest's summit altitude, but Messner was determined to climb the mountain "by fair means or not at all". Two years later, he made the first solo ascent, from Tibet and in full monsoon season.

He cut his teeth in the Dolomites, quickly progressed to the Alps, the Andes, and finally to the Himalaya. Yet his first ascent of an 8,000'er was wrapped in drama. A member of a large expedition up Nanga Parbat's huge Rupal Face, Messner and his younger brother Gunther continued when the rest of the team retreated. They had to descend in a blizzard, down the unexplored Diamir Face. Messner lost seven toes but Gunther never made it down.