On July 18, Polish paddlesports athlete Sebastian Szubski completed a solo kayak circumnavigation of Great Britain. He covered the 3,000km route in 37 days, finishing three days faster than Dougal Glashier, the previous record holder from 2023.

Szubski began his journey in Western Scotland on June 12 and initially faced challenging waves, fatigue, and changeable weather conditions that are typical of the British coastline. His route led him around Scotland’s rugged coast, down the coasts of England and Wales, across the Bristol Channel, through the Irish Sea, past both Ireland and Northern Ireland, and ultimately back to Scotland.

For much of the route, Szubski was neck-and-neck with Glashier's time, paddling an average of 80km to sustain his target of 40 days.

Key moments

“Scotland welcomed me as if it were paradise on Earth. Beautiful, with seals, views, and no waves because I was hidden among the islands. I decided to start higher than I had planned. It turned out I'd chosen the most beautiful spot in all of Great Britain,” Szubski told Red Bull Poland.

However, on day two, this short-lived idyllic start was replaced by rudder issues, a leak, and rough seas that left him unable to control his boat properly. He narrowly avoided crashing into the cliffs at the famous sea stack of the Old Man of Stoer.

From the seventh day, Szubski’s journey settled into its routine of paddling, eating, and sleeping. He often spent up to 16 hours a day in his kayak. The timing of his efforts was frequently dictated by tidal currents, sometimes requiring pre-dawn starts in gnarly weather. These early rises became essential for staying on schedule.

By the eighteenth day, he reached the halfway point. Navigating past Dover under the cover of night helped him avoid the world's busiest shipping traffic, though technical issues left him without lights or radio communication.

A support team followed Szubski the entire way. On land, recovery was the top priority, although each landing also required recording footage for Guinness record documentation, changing into dry clothes, and eating high-calorie meals. He received massages from his support team and slept, at least at times, in a rooftop tent.

Olympic pedigree

When Szubski announced his intention to circumnavigate Britain by Kayak, some in the British paddling community were skeptical. He had reportedly never kayaked at sea, let alone the rugged British coast, which can be technically challenging and dangerous.

In preparation, in July 2024, Szubski and Sebastian Cuattrin paddled a 200km section of the River Thames in England in just under 22 hours. A few months later, that fall, the Pole visited and trained with Mike Lambert, a former British canoe sprinter who completed a 58-day kayak circumnavigation earlier in the year.

Although born in Poland, Szubski represented Brazil in the 2004 Summer Olympics in the sprint canoe event and the 500m doubles kayak. He also holds the record for the farthest distance by canoe or kayak on flat water in 24 hours -- an impressive 252km.

Fastest known time

Szubski has claimed his circumnavigation as the fastest kayak journey around Great Britain, and a number of news sources have suggested he has broken a Guinness World Record. How Guinness will ratify this record is unclear, as they do not currently appear to have published a comparable record on their website. Also, for some in the adventure community, they are not a credible record-keeping organization.

Dougal Glashier previously held the fastest known time, although his route was reportedly 3,120km -- slightly longer than the 3,000km initially reported by Szubski. Both Glashier and Szubski had support crews, but details remain unclear regarding how much they relied on them, whether they camped wild or stayed in accommodations, and how similar their routes were.

In 2012, Joe Leach, the previous record holder, completed the journey in 67 days, a benchmark Glashier surpassed by an impressive 27 days.

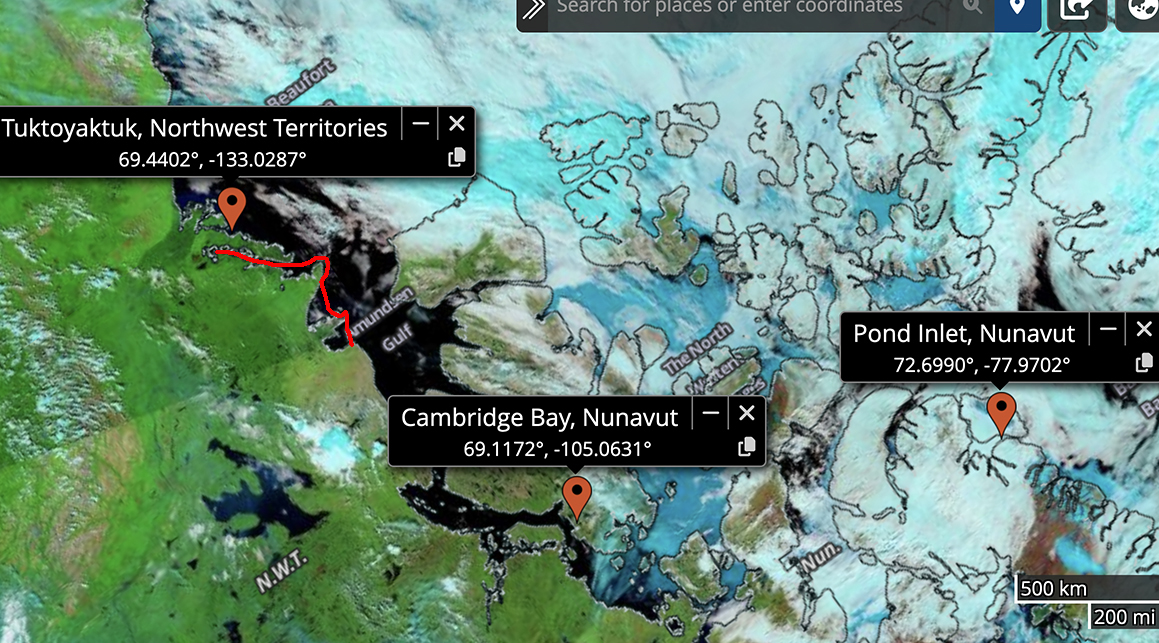

Last month, Canadian adventurers Dave Greene and Gaia Aish completed a 1,725km bike and canoe journey from the British Columbia border to the shores of the Arctic Ocean over 30 days.

The pair started on May 22 from the border of British Columbia and the vast Yukon Territory. To begin, they pedalled around 100km to a small settlement by the Yukon River, where they picked up their pre-stashed Canoes. "It was a good little break into the trip. A little gear shake down, if you will," Greene explained.

From here, Greene and Aish set out on a 746km canoe leg along the river, where they faced no major rapids or portages, but low water levels and snow melt made the journey challenging. As a result, they spent long hours in the boat, with paddling sessions stretching to 12 hours a day.

"We managed to cover significant distance by doing that; we were paddling 60, 70, sometimes 80km in a day," Greene reflected.

Yukon delights

Despite the long days, Greene enjoyed the Yukon River: "It was an incredible part of the trip, maybe the most memorable part for us."

This may have partly been because the two Canadians were treated to a host of wildlife sightings, including both moose and bears with babies, lynx, sheep, wolves, and even a wolverine.

Greene and Aish carried their bikes in the canoe down the Yukon. When they eventually reached the end of the canoe leg in the historic gold rush town of Dawson City, they left their rented canoes with a company that returned them to the south.

At Dawson, the duo got back on their bikes. On June 12, they headed out onto the Dempster Highway, Canada’s only road north to the Arctic Ocean. The cycle north took twelve days, and the 940km they covered was hard earned.

Greene and Aish pedalled through a summer heatwave, prompting night rides to avoid the intense heat. The gravel road and dry climate made finding drinkable water difficult, as well as turning the ride into a dusty affair.

"The Dempster is a gravel road. So, being as hot as it was, it was also extremely dusty. We had dirt kicked into our faces, in our ears at all times," Greene said.

The Midnight Pedal Paddle Party

A benefit of riding this far north is the extended daylight hours, hence Greene dreaming up the expedition moniker, the "Midnight Pedal Paddle Party."

"We were north of the Arctic Circle for the majority of this bicycle ride, which means that the sun was not setting. So we had 24 hours of daylight, which, after a certain amount of time, one just gets used to. You get tired enough that you can just lie down and sleep, but it also allowed us to ride our bikes whenever we wanted," Greene explained.

To ease some of the weight burden while cycling, Greene and Aish turned to the Dawson City Visitors Center, which allows cyclists to leave food boxes for pickup by drivers heading to Eagle Plains Hotel, a pit-stop 500km into their route. Additionally, they had a friend in the Northwest Territories, so they met with them to collect another box of food. At most, they had to carry seven days of food at a time.

To the ocean

The final 150km from Inuvik to Tuktoyaktuk were the most demanding of the expedition, thanks to the freshly gravelled road.

"It was four to six inches of fresh gravel and we had to push our bikes up all of the hills, because it was simply unrideable," Greene recalls.

Their spirits picked up when they reached the Arctic Ocean and the community of Tuktoyaktuk on June 23, marking the end of their trip.

"Getting to the Arctic Ocean was quite the thrill. The community of Tuktoyaktuk is an Inuit community in Canada, and we happened to arrive the same day they were having their indigenous day, a territorial holiday," Greene said.

Naturally, the weary -- and no doubt sweat-encrusted -- cyclists celebrated by jumping into the Arctic Ocean.

A group of young people from several Native American groups has completed a month-long journey down the Klamath River. The journey commemorates the removal of four dams, leaving much of the river to flow freely for the first time in a century.

Years in the making

Indigenous activists had been fighting for decades by the time the Klamath Basin Restoration Agreement was signed in 2010. The agreement promised to remove the four hydroelectric dams on the Klamath River. In November of 2022, federal approval finally came through for the dam removals.

The first and smallest, Copco No. 2 Dam, was removed in 2023, 98 years after it was built. In 2024, the other three dams -- Iron Gate Dam, Copco No.1 Dam, and JC Boyle -- were removed as well.

Paddle Tribal Waters, a nonprofit program teaching kayak and river advocacy to Indigenous youth from all along the Klamath basin, launched in July 2022. After years of training, 43 young kayakers ranging from 13 to 20 set out on June 12 from the Southern Oregon headwaters. There are still two dams remaining, near the headwaters, which they had to portage around.

The journey took them through canyons with rapids as well as across the choppy Agency Lake and through the dam removal sites. Those who had clearance tackled class 3, 4, and 5 rapids, while others chose to take those sections by raft.

In the last few days, even more young people joined. Youth from indigenous communities in the United States, Chile, Bolivia, and New Zealand took to the water. By July 11, a veritable flotilla, 110 strong, approached the mouth of the river. There, friends, family, and community members waited to welcome them.

A historic return

Now that the river flows freely, the ecosystem is beginning to repair itself. Important species like salmon, steelhead, and lamprey can now access over 600km of historic spawning habitat. The drained reservoirs no longer cause massive algae blooms, so the water quality is increasing and the temperature is decreasing. The speed of the river's recovery is a heartening surprise, even to its staunchest advocates.

"We were hopeful that within a couple of years, we would see salmon return to Southern Oregon. It took the salmon two weeks," said Dave Coffman, in a conversation with CNN. Coffman is the director of northern California and southern Oregon for Resource Environmental Solutions, which is working to restore the Klamath.

Klamath fish populations are a vital resource for Indigenous people along the basin, primarily the Klamath, Shasta, Karuk, Hoopa Valley, and Yurok peoples. But though salmon can now return, they return to a very different habitat. Industrial farming has reshaped and polluted the Klamath, and the federal government has frozen much of the funding for restoration.

The trip wasn't just a celebration, but a commitment to continue the fight. "It’s not just a river trip and it’s not just a descent to us," said Hupa tribal member and Yurok descendant Danielle Frank, a participant who gave a speech at the celebration. "We promise that we will do whatever is necessary to protect our free-flowing river."

An all-female team known as the "Hudson Bay Girls" is more than a month into a self-supported 1,900km canoeing expedition from Grand Portage on Lake Superior to York Factory on Hudson Bay.

Their route follows traditional waterways first traveled by the Anishinaabe people, and later used by French fur traders in the 18th and 19th centuries to connect remote trading posts across the Canadian wilderness.

The journey, expected to take 85 days, began at the end of May with a challenging 13km portage, known locally as "Grand Portage." From there, the team paddled 400km through the pristine Boundary Waters wilderness area, which is threatened by proposed mining projects.

Building on experience

The team has plenty of paddling and wilderness experience, having collectively paddled over 6,400km. The foursome of Olivia Bledsoe, Emma Brackett, Abby Cichocki, and Helena Karlstrom has varied backgrounds, including roles as wilderness canoe guides, wilderness medical technicians, and trail maintenance foremen in the Boundary Waters and Quetico Provincial Park.

The Route Ahead

Recently, the expedition passed through Voyageurs National Park. They stopped to resupply at the city of International Falls, Minnesota, which straddles the U.S and Canada border. The next leg of their journey involves paddling north across Lake of the Woods, a vast body of water notable for its thousands of islands and indigenous heritage.

Following Lake of the Woods, the team will navigate the 240km Winnipeg River. From there, they'll paddle along the eastern shores of Lake Winnipeg for three to four weeks, likely contending with shallow waters and large swells.

The expedition's final stretch is the 480km Hayes River, a Canadian Heritage River historically used by the Hudson Bay Company as a key trading route. The river transitions dramatically from boreal forest to sub-arctic tundra and is home to several Cree communities.

All being well, the Hudson Bay Girls' journey will culminate at York Factory -- a historically significant trading post pivotal to Canada's fur trade era -- in Hudson Bay.

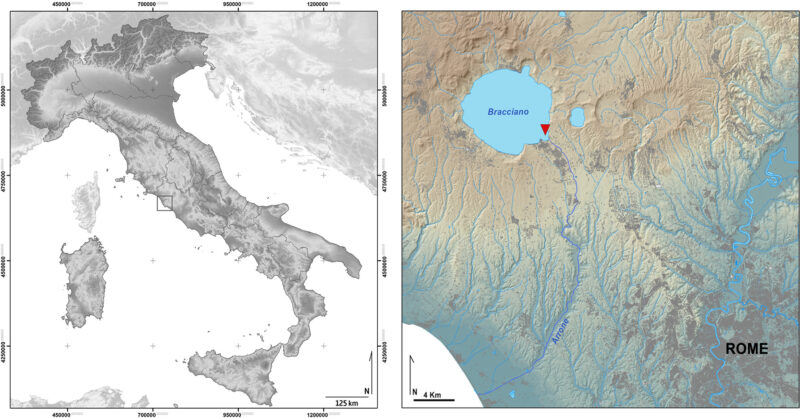

About 30,000 years ago, humans arrived in Japan's southern Ryukyu Islands, 110km from Taiwan.

The archaeological record hasn't preserved any clues as to how these Paleolithic people made the crossing to this new land. But the obstacles to doing so seem, at first glance, insurmountable without modern technology and knowledge. So in 2013, a group of Japanese archaeologists set out to recreate the trip using only Paleolithic tools.

This week, they published the results of their experiments in the journal Science.

A challenging crossing

Archaeologists find evidence of humans in the Japanese archipelago as early as 35,000 BCE. Judging from the dates at different archaeological sites, the earliest inhabitants of Japan seem to have migrated both northward from Taiwan and southward from Korea.

But from the Taiwanese coast, the low-lying islands of Ryukyu sit below the horizon. One of the strongest currents in the world, called Kuroshio ("Black Tide"), runs northward from Taiwan. It carries any lackadaisical drifters west of the Ryukyu Islands at a velocity of one meter per second. And a distance of 110km from Taiwan to the nearest Ryukyu island, Yonaguni, was no joke for people without metalworking or sails.

Yet they made it.

When the Japanese archaeologists set out to recreate this trip, they didn't have an easy time. They tried reed-bundle rafts and bamboo rafts, both of which floundered in the strong current. The bamboo also began to crack and fill with seawater, further weighing it down.

The beginning of the voyage

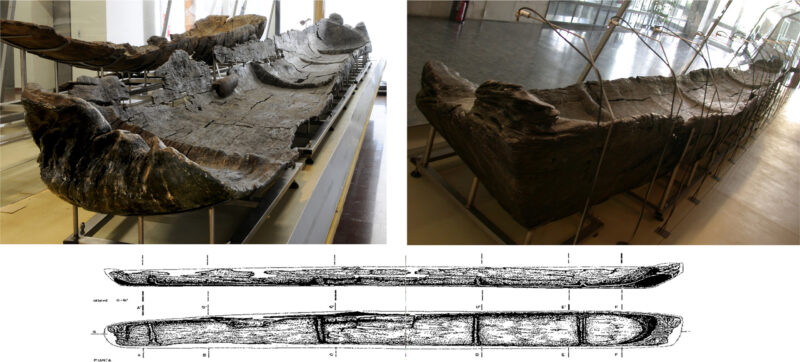

In July of 2019, the team attempted one final trip. They launched Sugime, a hand-made dugout canoe, from the coast of Taiwan in typical calm summer weather.

Construction of the dugout started in 2017. The team used replicas of stone axes found in Japanese Paleolithic sites to fell a one-meter-thick Japanese cedar tree. They peeled off the bark and carved a seating area in the center of the trunk. While dugout canoes from the Paleolithic haven't survived in Japanese archaeological sites, dugouts from the later Jōmon period (starting around 14,000 BCE) boast burn marks on the inside. In turn, the team polished the inside of their craft with fire.

The plan was simple: to row from Wushibi, on the eastern coast of Taiwan, across the strait to the small Ryukyu island of Yonaguni. A motorized ship with safety supplies would escort the Paleolithic reenactors.

Sugime's crew consisted of five paddlers, four men and one woman. For the first hour and a half of their journey, they skidded over a calm sea, with only wispy clouds on the horizon. Then the water depth dropped, and they hit the edge of the Kuroshio. The wind slammed into the current, giving rise to choppy water and an ever-present swell as high as the side of their boat. One of the crew had to pause paddling to bail out the dugout over and over again.

They kept rowing into the night. The wind dropped slightly, but the dugout kept threatening to capsize in the strong swell. There was no rest that night, and it was a constant fight to keep the nose of the dugout pointing northeastward. As the water approached a flow of 1 m/s, the dugout pivoted northward along with the current.

Just as steering the boat was a challenge, so too was figuring out where to steer it. Clouds obscured the stars, and GPS wasn't an option in the Paleolithic. Only the direction of the swell indicated which way was north.

As midnight approached, the wind dropped and stars appeared. The paddlers took turns resting. But in the early hours of the morning, clouds once again obstructed the stars. At 3:40 am, while the captain was taking his rest, one crew member thought she saw dawn on the horizon. The crew pointed the dugout accordingly.

Then the captain woke up. The dugout was traveling due north, dragging them off course from their destination. He realized that far from being dawn, the light on the horizon was from the northern cities of Japan and was reflecting off the clouds. Sugime turned eastward once more.

Exhaustion and triumph

The next day dawned bright. Still unable to see their destination, Yonaguni Island, the crew kept paddling east-southeast to combat the current of the Kuroshio. Unbeknownst to them, however, they had left the Kuroshio behind them. They were now heading due east, away from Yonaguni.

They had already exhausted all the water they had packed for the voyage. Tired and thirsty, they called in a resupply. At noon, finding themselves in calmer waters and realizing they had left the Kuroshio, the whole crew slept for half an hour.

As they paddled into the afternoon, Yonaguni still failed to appear. They steered the dugout this way and that, hoping it would peek above the horizon. It didn't. Moreover, the crew was exhausted. Some of them jumped into the ocean to rest in the cool water. But nothing prevented the onset of excruciating muscle cramps and, as evening drew close, hallucinations.

Then, just before the sun set, a bird flew overhead. Before this, the sea had been lifeless and isolated. Now, land was near, even if they couldn't see it.

The sun was so intense that the food they had brought with them began to rot. They obtained replacements from the escort ship and ate a dinner of rice balls and noodles. As night slid in, the crew rested while the boat drifted loose on the water.

The captain kept watch. He thought he saw the glint of a lighthouse on the horizon that he hoped was from Yonaguni. As it turned out, it was an optical illusion, but the swell carried the dugout gently northeastward. In the early hours of the morning, the actual light from Yonaguni's lighthouse appeared on the horizon.

When the crew awoke in the dark hours before dawn, they began the final stretch of their journey toward it.

It was not until just after dawn on the third day that the crew finally saw Yonaguni Island. They were 20km from shore and had been rowing for over 40 hours.

Five hours later, they reached land. Since their crew included Taiwanese paddlers, they had to follow immigration protocol and land Sugime at a predetermined beach. Paleolithic explorers, presumably, did not have this restriction.

Piecing together a Paleolithic voyage

The crew had made it. Dugout canoes, unlike reed and bamboo rafts, can cross the Kuroshio. But at various points during the trip, the crew's mistakes had worked in their favor. When they rested, the swell naturally carried them in the right direction. And the first hint they saw of Yonaguni was from a lighthouse, which does not feature in Stone Age archaeological sites. Was their success a fluke?

To test this, the team used the data from their paddling to simulate hundreds of dugout voyages starting from different points in Taiwan. They used both modern and Paleolithic oceanographic models to approximate the flow of the Kuroshio, varying the strength of the current between ebbs and peaks. As long as the virtual boats paddled in the right direction, they made the crossing, even when the Kuroshio was at its strongest.

But the voyage could not be completed by accident. The Kuroshio does not carry mariners from Taiwan comfortably to the shores of Yonaguni. Paleolithic humans had to identify the direction and strength of the Kuroshio and plan their voyage accordingly.

They also had to know Yonaguni was there. From the coast of Taiwan, it is not visible. Only when one climbs the mountains in the north does the little speck of island appear over the horizon. The summit of the highest of these mountains sits at nearly 4,000m.

This research in experimental archaeology shows that inhabitants of Taiwan 30,000 years ago did not drift aimlessly towards the Ryukyu Islands. They climbed mountains, they built sturdy boats, and they knew how to chart a course against one of the strongest currents in the world.

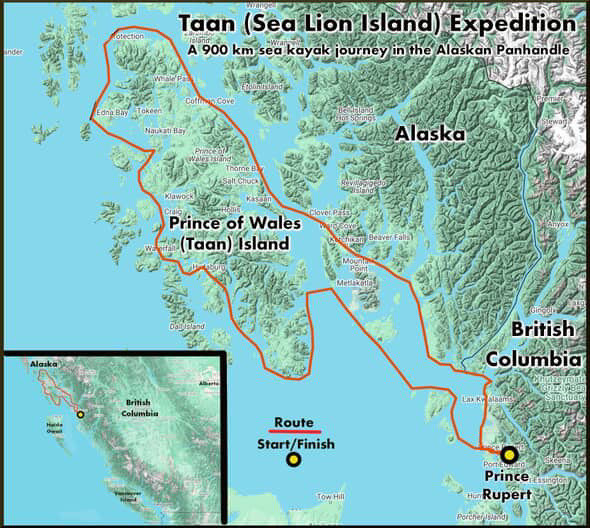

Canadian adventurer Frank Wolf and teammate David Berrisford have finished a 720km sea kayaking expedition through southeastern Alaska. Originally planned as a 900km circumnavigation of Prince of Wales Island, the pair had to change their route due to heavy spring storms.

"We had to sit out two of the first six days due to heavy southeast storms," Wolf reported. "We adjusted to our Plan B route...that would give us more cover for the 25 days we'd budgeted."

The trip marked the first Alaskan kayak expedition for both paddlers. Wolf has extensive experience along the British Columbia coastline, but Alaska was an entirely new challenge.

Their adapted route involved several open water crossings ranging from 8 to 14km, with strong currents and waves.

While the route changed, the rewards remained. The team paddled through temperate rainforest coastlines, camped in old-growth forests, and saw brown bears, orcas, humpback whales, porpoises, sea otters, and elk.

A nine-day storm

As the team neared the end of their journey, a series of powerful storms hit them just 90km from their final destination of Prince Rupert, British Columbia.

“We were pinned in just above Cape Fox in Alaska, where the entire fury of the notorious Hecate Strait slams,” Wolf reported. The strait is known for producing some of the largest waves in the world.

With time running out and no transport options available across the Canada and U.S. maritime border, the pair eventually asked members of the Nisga'a First Nation to pick them up during a brief break in the weather.

“There is no ferry or other transport service over the border, so in the end only the Nisga'a...could get us,” said Wolf. The Indigenous group has special status, allowing them to move freely over the borders.

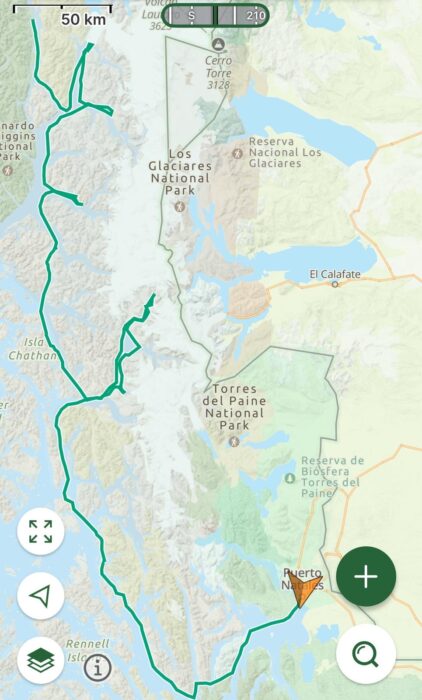

Earlier this month, three kayakers completed a 32-day expedition through remote southern Patagonia. They covered nearly 900km of isolated fiords and rugged coastline.

Mathew Schweizer and Brody Duncan of New Zealand, along with Andy Gill of Scotland, began in Puerto Edén, a remote fishing village in the Magellanes region of Chile.

Before setting out, the group underwent an official gear inspection from the Chilean Navy.

“We had a naval inspection to check all our gear and get signed off… We needed to get permits from the Navy,” said Schweizer.

South America's largest glacier

Before heading south, the team paddled north from Puerto Edén to the Pio Xi, the largest glacier in South America.

“Absolutely huge, about five kilometers wide,” Schweizer noted.

They explored nearby fiords but had to turn back because of dense ice.

“The amount of ice that was coming out was just too much for us to paddle up into. Just big big ice pack.”

Their journey included an overland portage through a lake system.

“It was pretty hard work, unloading all the gear and hiking through some hard terrain, and then carrying kayaks up and over hills and into these lake systems,” Schweizer said.

Later, they entered Peel Fiord, a vast network of channels stretching roughly 70km. At its northern end lies Seno Andrew Fiord, which Schweizer described as a standout moment. “Just amazing. Four or five glaciers running straight down into Seno Andrew [Fiord].”

The coastal fiords of Patagonia, located in the Magallanes region of southern Chile, are among the most remote and least inhabited areas of South America. Known for challenging weather and dramatic glacial landscapes, the region is accessible only by boat or on foot.

Rough paddling weather

Adverse weather was a challenge throughout the 32-day trip.

“Probably four-and-a-half-foot waves,” Schweizer recalled of one particularly rough stretch.

The team also faced equipment failures. “Broken holes and tents, broken sleeping mats, well, my broken sleeping mat had fifteen or so puncture repairs on it. It just failed on me.” Strong winds also shredded their tarp.

In total, they covered 850 to 900km, and ended in Puerto Natales, a port city a few hours of Punta Arenas, the jumping off point for flights to Antarctica.

The isolation of the route demanded complete self-reliance.

“Once you start paddling from Puerto, you have no other villages, no other civilization to come across…There's no help. There are no people out there,” said Schweizer.

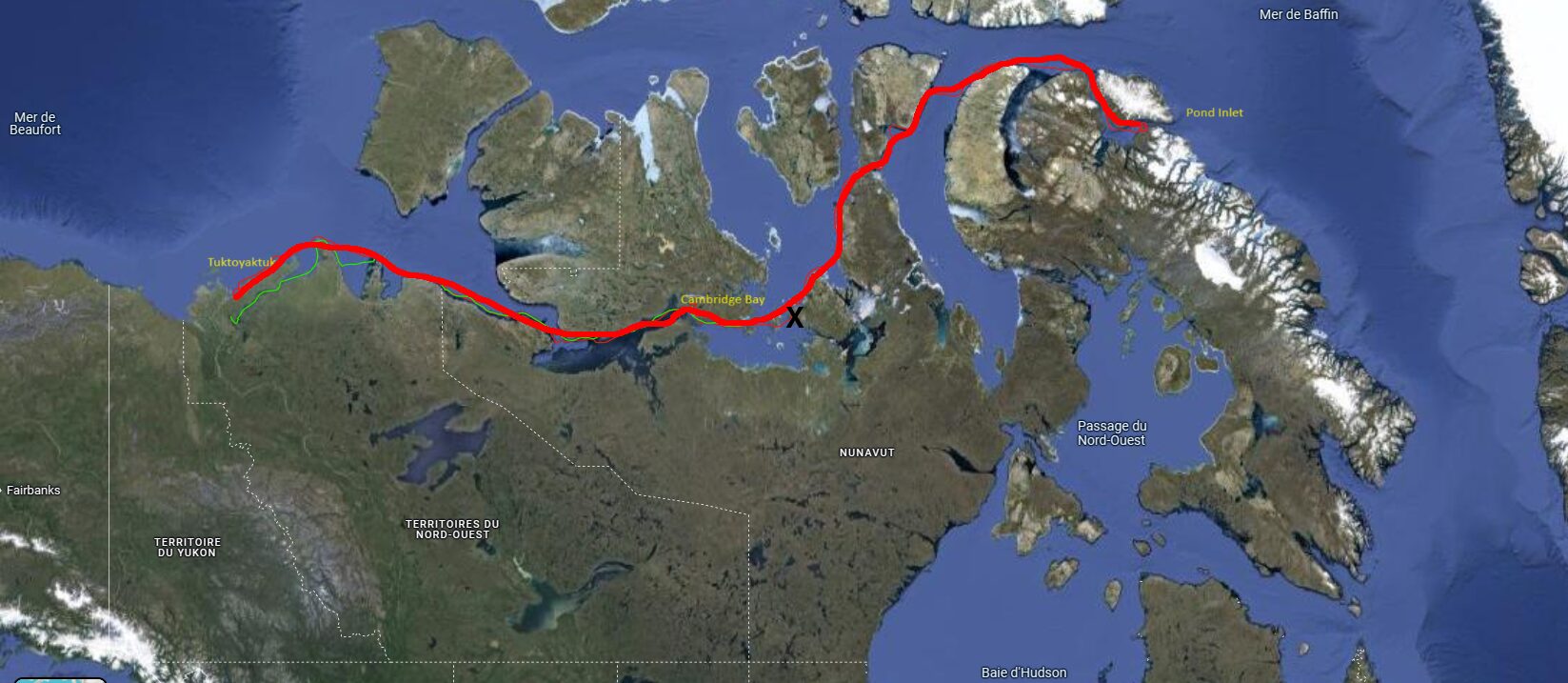

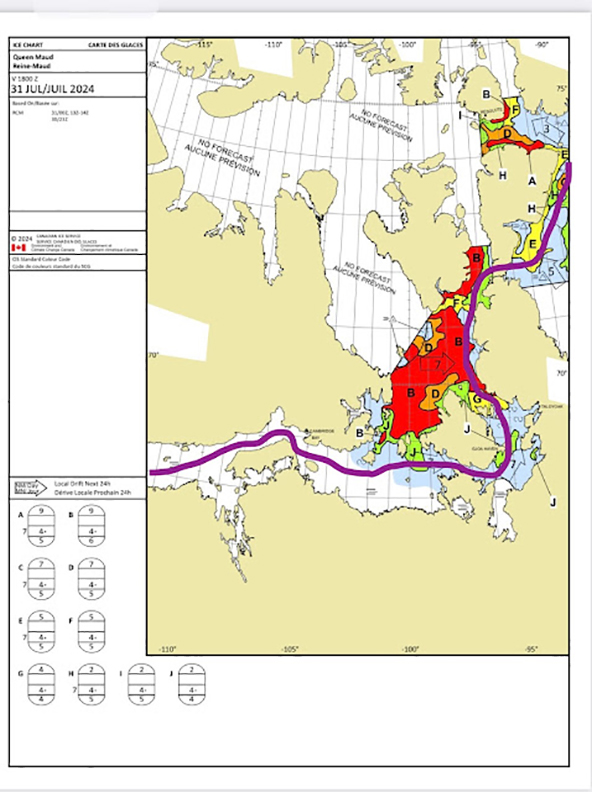

In two weeks, Dave Greene and Gaia Aish will set out on a 1,700km canoe and bike journey through northwestern Canada to the shores of the Arctic Ocean.

The pair, who are life partners as well as teammates, will start biking from the Yukon-British Columbia border. After 100km, they will retrieve their canoe at Johnsons Crossing, a small settlement at the head of the Teslin River.

They then swap pedal power for paddle power, stowing their bikes in the canoe. Over 12 days, they will canoe 750km down the Teslin and Yukon Rivers to Dawson City. From this famed Gold Rush town, the pair will reassemble their bikes and ride 940km north over the Dempster Highway to Tuktoyaktuk in the Northwest Territories.

The Dempster Highway is Canada’s only road north to the Arctic Ocean. As they cycle north on this gravel road, Greene and Gaia will cross two mountain ranges -- the Ogilvie and the Richardson -- before descending to the Mackenzie River delta at Inuvik and ending in Tuktoyaktuk. On the first section of the Dempster, the pair will hike in the striking Tombstones range.

Greene and Gaia are based in Nova Scotia and are currently on sabbatical from their jobs in education. Last month, Greene completed a 400km ski crossing from Akulivik to Kangiqsujuaq in northern Quebec. Before that, he had undertaken nine canoe, ski, or bike journeys. Aish has previously canoed in Labrador. They estimate their trip will take 30 days.

This weekend, Canadian adventurer Frank Wolf and teammate David Berrisford will start a 900km sea kayak journey in the waters between Alaska and British Columbia. Starting and ending at Prince Rupert, B.C., the duo will paddle around Prince of Wales Island, off the Alaskan Panhandle. It is the fourth-largest island in the United States.

“I’m not too sure what we’ll find up there - it’s a new zone to us,” said Wolf, who has made many human-powered journeys around North America. “I’ve pretty much paddled the entire British Columbia coastline, so pushing up to explore the Alaska coast is the natural next step. There will be a few big crossings along the way, and outer coast spring conditions to contend with.”

Prince of Wales Island is the home of the indigenous Tlingit peoples and is known locally as Taan, the local Tlingit word for sea lion. In Tlingit culture, sea lions symbolize endurance.

The journey is expected to take Wolf and Berrisford around 25 days.

Johnny Coyne has become the first person to kayak from Ireland to Asia. The Irish adventurer set out in September 2024 with Liam Cotter. Countryman Ryan Fallow joined the duo later. But only Coyne did the entire distance.

At first, he and Cotter crossed the Irish Sea and the English Channel without support vessels. Then they navigated through numerous European rivers and canals. It wasn't easy -- and not just because of the physical effort.

In France, they didn't have the right permits, so they were banned from the canals. By the time they sorted that out, the waterways were frozen. Determined to keep their journey human-powered, they dragged their kayaks 350km cross-country through France and then Germany’s Black Forest to the source of the Danube.

This lengthy portage was one of the hardest parts of the expedition. At one point, the wheels of their kayak cart broke, and they were forced to stop for weeks. Winter took hold, and the temperatures plummeted.

Onto the Danube

In Germany, Ryan Fallow joined the expedition, and the trio took to the Danube. The three paddlers were used to rapids, but anticipating the right lines on an unknown river was nerve-wracking. In Austria, disaster struck. Cotter’s boat smashed into rocks in some rapids, opening a significant hole. But chance smiled on the young travelers: They stumbled across two good Samaritans -- one who repaired the boat and another who replaced Fallow’s old, unsuitable vessel with a newer one.

Back on the Danube, Cotter dislocated his shoulder during a portage and could not continue. Coyne and Fallow soldiered on through Slovakia and Hungary, where more border crossing problems ensued. On their first night in Croatia, police surrounded their kayaks, convinced they were illegal immigrants.

Yet the pair persisted with unwavering positivity. From Croatia, they paddled through Serbia, Romania, and Bulgaria, resupplying at various towns. Most of the time, they camped along the riverbank but occasionally accepted hospitality from locals.

As the months passed, their equipment began to fail. Their tent leaked, and some of its poles had been lost. By the end of their eight-month crossing, it was held together with tape and sticks.

The Black Sea at last

At the start of April, 210 days after setting off, they reached the Black Sea, their last major milestone before Istanbul. The next big goal was to reunite with Cotter so that he could join them at the finish. After the shoulder injury, Cotter couldn't paddle but he had remained in the wings, helping with logistics. Now the trio wanted to finish together.

Cotter wanted to stick to their human-powered plan, so as soon as his shoulder mended enough, he started cycling to catch up with his pals in Bulgaria. On day 225, he rejoined them after three months apart, ready to kayak with them for the last week.

The final week started with paddling from Bulgaria into Turkey. Once again, the border crossing was anything but simple. Coyne tried to arrange their entry with the Coast Guard, and a customs boat met them as they approached the border.

However, it informed them that they were not allowed to land. They had to wait on the Bulgarian side in their boats for three hours. The temperature dropped, the water became choppy, and it was dark before they were allowed to get off the water. But still not in Turkey.

Another troublesome border

On the beach, police questioned them and searched their kayaks. As they slept that night, the police refused to leave, to ensure they would not cross the border overnight. The next morning, they were finally allowed to cross into Turkey.

With four days left, their excitement was palpable and only increased when a pod of dolphins swam next to them as they paddled along the Turkish coast. On April 25, they landed in Istanbul to cheers from the friends and family who had come to meet them.

“This has been the greatest moment of my life so far,” Coyne commented as he exited his kayak.

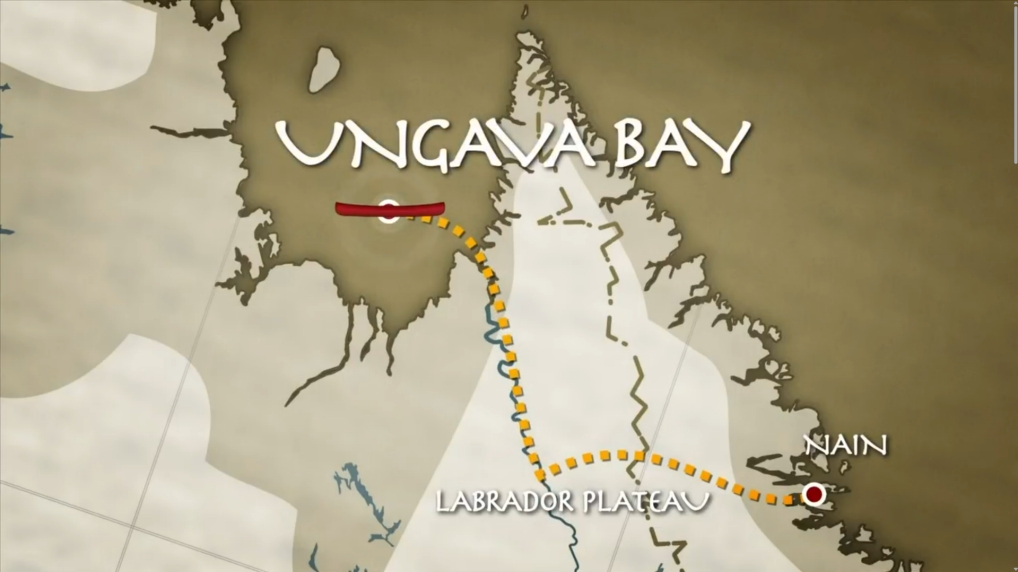

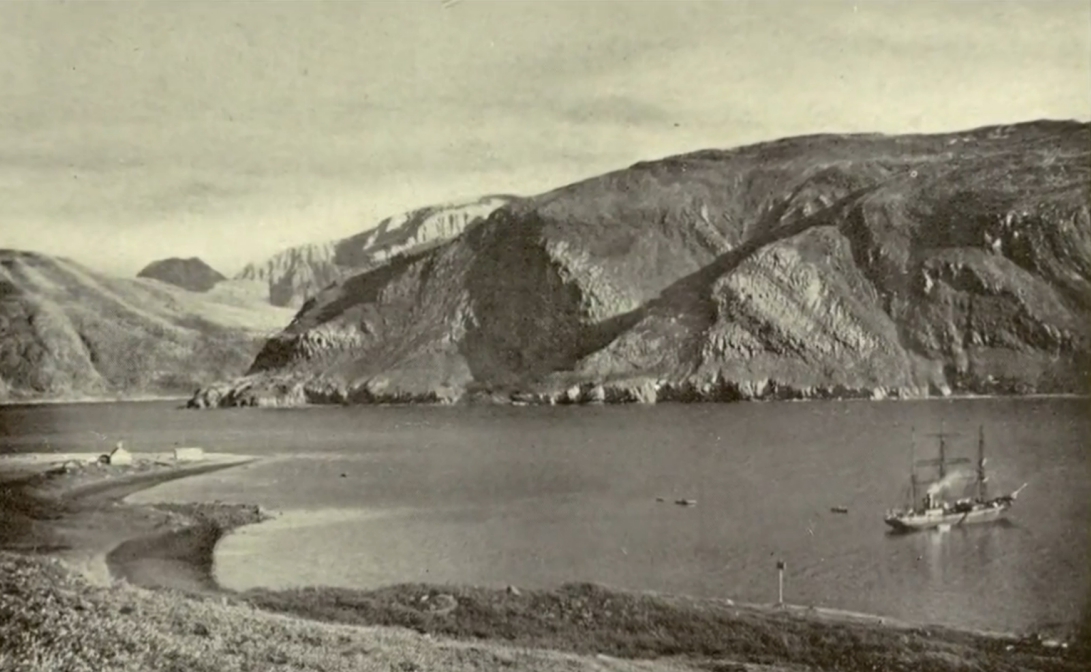

Kitturiaq chronicles a 620km canoe expedition across the Labrador plateau down the George River in Canada's northern Quebec. Professional adventurer Frank Wolf undertook the journey with partner Todd McGowan.

Wolf is bold in adventure planning and is perfectly willing to be bold in filmmaking, too. The film's narration is delivered by a fictional mosquito who chooses to tag along as an unofficial third party member. In fact, the Inuktitut word for mosquito gives the project its title.

Meanwhile, the Kitturiaq, named Malina, shares the story of explorer Hesketh Hesketh Prichard. (Evidently, his parents felt that one "Hesketh" wasn't enough.) Through Malina's narration, the story of the Briton's failed 1910 attempt to complete the route unfolds simultaneously to the main action.

The journey begins in Nain, now the northernmost town on the Labrador coast and the administrative capital of the Inuit region of Nunatsiavut. There, Wolf interviews local community leaders about the land his upcoming journey will take him through.

A 600m climb, with canoe

The first stage takes them a little north to the giant Fraser Canyon, which they must scramble up to the Labrador plateau. Malina's blackfly relatives are thick in the air, just as locals warned they would be.

But it's the portage they have to make that is the real killer. With no waterway to follow, they have to unload their gear, then drag it and the canoe 600m up a crack in the cliffs called Poungassé to the top of the plateau. Sweat and blood cover them both by the time they reach camp, and McGowan suffers sunstroke. The long subarctic summer day can be blisteringly hot.

They're still doing better than Prichard, who took a steeper route and ended up abandoning one of his canoes. Atop the plateau, Prichard saw no waterways -- the plateau is mostly swamps and shallow ponds in this area -- and abandoned his last canoe, continuing on foot. Wolf and McGowan elect to drag theirs. After a brief descent into fly-induced madness, they're back on the water.

"People have been here, a long, long time before us," Wolf reflects, examining a piece of wood. No trees grow on the tundra, so an Inuit hunter must have brought the discarded log on his sled, or komatik, years before. This small moment is a quiet reflection on a core theme of the film.

The paddling and portaging continue. "They're beginning to act a little strange," Malina notes. A headnet makes a reappearance.

When they make it to Nunavik, they go fishing, while Nain politician Johannes Lampe reflects through a previous interview about how prohibitively expensive food is this far North. Caribou is much more cost-effective than groceries, and fishing is cheaper than buying fish. The land takes care of you, Lampe explains, when you take care of it.

The George River

When Prichard and his team reached the George River, they hoped to meet the local Innu people. But these elusive people had already passed on to different hunting grounds. Without any canoes to handle the George River, Prichard had to turn back.

But Wolf and McGowan's portage drudgery paid off, and they still have theirs. Once they reach the George River on day 17, the kilometers begin to fly by. Speaking of flies, they remain innumerable. Soon, the canoeists reach the end of the river at Ungava Bay.

At 23, Kyle Parker paddled all 682km of the Wisconsin River in a blur of muscle fatigue and no sleep. Coming in at 5 days, 19 hours, and 22 minutes, he set the fastest known time for the route in a solo canoe.

Parker wants to take his time for his new project, which will begin in just under a month.

"Today, we travel by all sorts of modes, often opting for the easiest and fastest we can find," he writes on his blog. "I am looking forward to slowing down to just a few miles an hour and really getting under the skin of the country."

The U.S. from 'tip to tip'

Parker's big dream is to traverse the country from northwestern Washington to southeastern Florida. He expects the trip to take six to eight months.

The route encompasses the frigid, deep waters of Puget Sound, hundreds of kilometers of rivers across the continental United States, the warm waves of the Gulf of Mexico, and even a few days on the western seaboard of the Atlantic Ocean.

He will have to contend with more than just choppy water and fierce currents. Usual canoe routes feature regular portages over dams when the interruption of the river requires carrying the canoe. But Parker will have to portage hundreds of miles over highways and, on one occasion, the continental divide.

"But it’s not just about the scenery or the wildlife, or even the excitement of being absolutely miserable," Parker writes. "It’s also about the people I’ll meet and the stories I’ll uncover. I want to connect with locals...and experience the culture of each place I visit."

Carrying on Stachovak's legacy

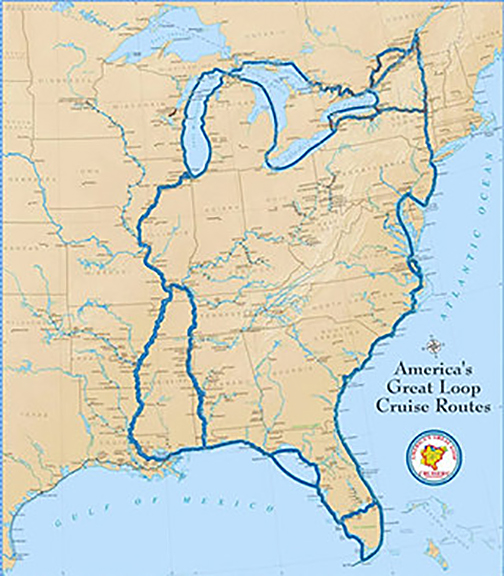

This kind of expedition is unusual but not unheard of. In 2009, Parker's fellow Great Lakes native Jake Stachovak completed the 9,237km Great Loop by kayak. The Great Loop starts in Portage, Wisconsin, and ends in Portage, Wisconsin, with a brief detour to the Gulf of Mexico. In 2022, Stachovak passed away to cancer at the age of 46.

Now his widow has supplied 24-year-old Kyle Parker with a portage cart, water bag, radio, and a pink cup holder that all belonged to Stachovak.

Parker has support from local paddling stores, too. Ethan Scheiwe, the manager of Madison's Rutabaga Paddlesports and one of Parker's sponsors, told the Wisconsin State Journal, "It’s a very daunting trip, but Kyle is the right person for it. If he does this, it will be the National Geographic adventure of the year. It’s that kind of trip.”

Parker sets out on May 1. You can follow the adventure on his blog.

In September 2024, Johnny Coyne and Liam Cotter of Ireland, both 24, began an ambitious 5,000km kayaking journey from Dublin to Istanbul. Their route has taken them across the Irish Sea and the English Channel without support vessels, followed by tricky navigation through European rivers and canals. With 4,000km behind them, their finish line is now almost in sight.

Among the many challenges over the past seven months, their support vessel pulled out just hours before crossing the heavily trafficked English Channel, so they had to go it alone. They tried paddling the French canals but didn't have a permit, so they were banned from the water. By the time their paperwork was in order and they could restart, the waterways were frozen.

Undeterred, they put their kayaks on wheels and dragged them for 350km cross-country. Then, more bureaucratic issues on Germany's canals forced them to trek, kayaks and all, through the Black Forest to the source of the Danube.

Throughout it all, the Irish duo has shown relentless optimism, dismissing the many obstacles as just part of the experience. Coyne said the hardest parts have been the long sea crossings, particularly the 12-hour crossing of the Channel.

“We always say the hardest part is over, and then it just gets harder,” he told one interviewer.

Two become three, briefly

In Germany, the duo morphed into a trio. Fellow Irishman Ryan Fallow, 24, has joined the ranks and is sticking with them all the way to Istanbul.

By February, they had covered over 1,900km, reached the Danube River, and followed it into Austria. The first few days on the Danube were great fun, and with the current and occasional rapids, they covered around 50km a day. Then in some whitewater, a rock hit Cotter’s boat and put a hole in it.

Improbably, they found someone nearby who could fix it for them. When another man arrived to help with the repair, he offered Fallow another kayak to replace his old one with little storage. They took to the Danube again. Days later, during a long portage, Cotter fell and hurt his shoulder. He tried kayaking with his arm in a sling but it didn't work so well and he had to drop out. Three were two again.

More bureaucratic mishaps

They followed the Danube through Austria, then kayaked through Slovakia and Hungary. Six months after setting off, they entered Croatia. More drama ensued almost as soon as they arrived in their ninth country.

During their first night in Croatia, they woke up to police around their kayaks. They had to convince them that they were not illegal immigrants. The boys were allowed to continue, but they were told that they had to get a Serbian passport stamp. This is because they were paddling past Liberland, a patch of disputed land between the two countries.

A police boat followed them the entire way. After coming back into Croatia, they went into town for lunch but were arrested. They had not stamped back into Croatia. After a few hours and a 130 euro fine each, they were released.

They kayak every day but also explore the towns and villages they pass. Often, local people offer them a place to stay. Sometimes, they crash in fire stations. Most of the time, they simply camp on the riverbank. With the coming of spring, this has become far more enjoyable, although the winds on the water have picked up.

Continuing down the Danube through Serbia, they woke up one morning to find the water level had risen far more than they expected, washing their kayaks away overnight. Luckily, they found them slightly further downriver. Someone had spotted the boats on the water and pulled them ashore.

Arrested again

Strong winds then forced them to pull up on the Romanian side of the river. Once again, they had not had their passports stamped and were arrested. After a night in jail, they were released.

They will now paddle down the remainder of the river and then to the Black Sea, where they will follow the coast to Istanbul.

It doesn't affect the magnitude of kayaking alone across the Atlantic but it does put an asterisk on the achievement.

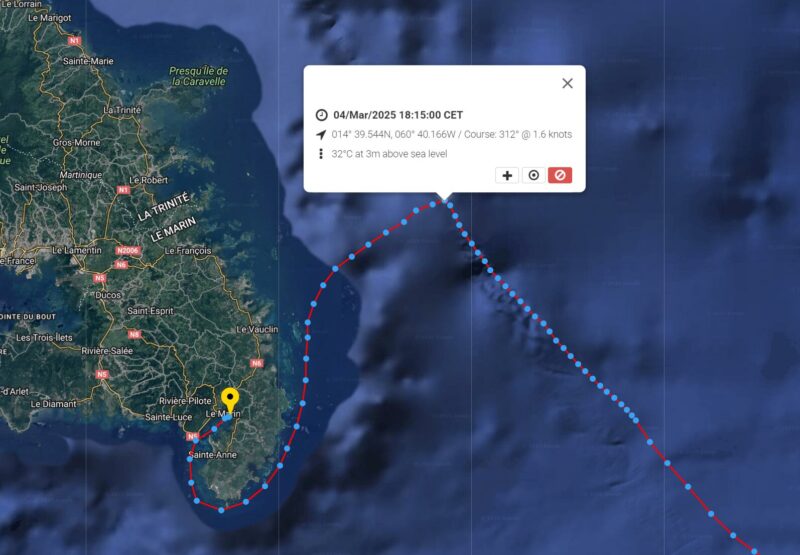

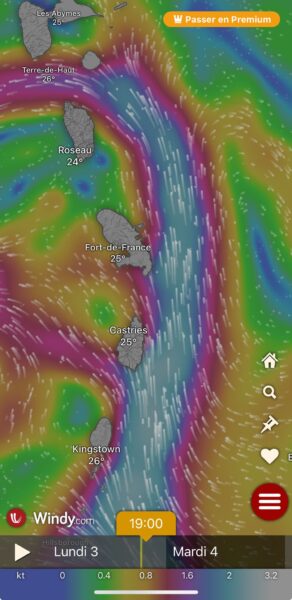

Two weeks ago, when Cyril Derreumaux approached the harbor of Le Marin in Martinique after kayaking 4,630km alone from the Canary Islands over the past two and a half months, he encountered strong winds and an unexpected northward current of almost two knots that he couldn't fight against. At the time, he was 45km from finishing.

He had two options. Either continue drifting and attempt to land days later in Guadeloupe, near the Dominican Republic, or accept assistance. Since his entire support crew was already in Le Marin, and even his Airbnb accommodations were set up, he decided to accept a tow from a support vessel.

There's no question that he had just kayaked alone across the Atlantic, but the short bit of assistance means that the journey no longer qualifies as unsupported. It also disqualified him from some of the Guinness records he might have wanted to claim.

"It doesn't negate the scale of what was achieved," he told ExplorersWeb after explaining what had happened.

First to kayak Atlantic and Pacific

Indeed, Derreumaux completed a human-powered east-to-west crossing of the Atlantic Ocean and was the first person to kayak alone across both the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans. The Atlantic crossing took him 71 days, 14 hours, and 57 minutes.

The crossing tested Derreumaux’s resilience to the extreme. In the first few days, he faced seasickness and sleep deprivation. Then there was the relentless toll of paddling for more than 10 hours a day.

Strong winds and huge waves buffeted his small craft, and he spent several days on his para-anchor. Vast patches of seaweed also slowed him down. His water maker failed on day 55, and he had to desalinate his water manually, a slow process. The lack of abundant fresh water meant he couldn't wash away the sea water, which left him with sores all over his body.

French alpinist Mathieu Maynadier and former Croatian alpine ski racer Ivica Kostelic did not expect to end their multi-sport adventure in a hospital bed. The pair had to be rescued after a storm swept their kayaks offshore in the Adriatic Sea.

The two athletes and filmmaker Bertrand Delapierre were attempting the first recorded ski traverse of the Albanian Alps, also known as the Accursed Mountains. The range lies in coastal southeastern Europe and spans the borders of Albania, Montenegro, and Kosovo.

The trio combined ski mountaineering, paragliding, cycling, and a final kayaking segment down the Bojana River to the Adriatic. The traverse was to showcase the region’s potential for extreme sports.

Swept out to sea

On March 10, after four days, they reached Lake Skadar. From there, they kayaked about 30km down the Bojana River to its outlet.

But as the river opened into the Adriatic, strong winds and waves of three to four meters swept Kostelic and Maynadier out to sea. Delapierre managed to reach the Albanian shore and alerted rescue services.

The Montenegro military responded. Five hours after the distress call, at around 10 pm, a naval vessel rescued Maynadier and Kostelic. A helicopter provided thermal imagery to locate the pair.

The extreme weather complicated the rescue, but finally, Kostelic and Maynadier were recovered and taken to a hospital in Montenegro. They were released the following day.

”We were tired and cold after four hours of fighting the waves, but...everything is now fine,” wrote Maynadier on social media.

He admits they made a mistake by entering the ocean in those conditions.

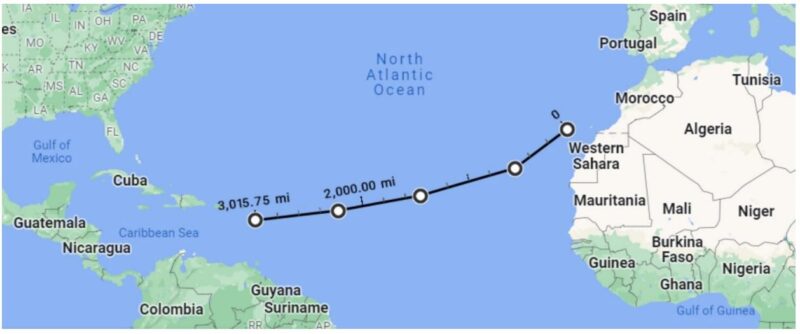

Yesterday, Cyril Derreumaux completed his solo kayak journey across the Atlantic Ocean in 71 days, 14 hours, and 57 minutes. He has thus become the first person to kayak alone across both the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans.

Derreumaux left from La Restinga in the Canary Islands on Dec. 23, 2024 and began paddling 4,630km to Martinique.

The early weeks were a struggle. The first few days featured seasickness, lack of sleep, and the aches of getting used to paddling at least 10 hours a day. Then he had to contend with constantly changing winds. Often, he made progress during the day only to drift back significantly at night. Several times, he had to take refuge in his cabin, put the kayak on its para-anchor, and wait out the strong winds and waves.

Valentine is no off-the-shelf kayak. It was custom-built for ocean crossings. Most significantly, it has an enclosed cabin for sleeping. It also has solar panels, an external antenna for making phone calls to his land team, and a pedal system. This means that besides paddling, Derreumaux was able to pedal to propel himself forward.

After the first few weeks, the weather became slightly more favorable. Once in a while, it even helped him go in the right direction

Blisters and sores

Nevertheless, the constant exposure to saltwater took a toll on his body. His hands, feet, and back have suffered the most. Blisters and sores couldn't heal due to the constant dampness. This situation worsened on day 55 when his electric water maker broke. Since then, washing properly was difficult, and he relied mainly on baby wipes. In his near-daily updates, he noted that mushrooms seemed to be growing under his fingernails, as they did on his Pacific crossing.

The failure of his water maker also meant that desalinating seawater into drinking water was slow and difficult. He had to filter manually, a time-consuming and physically demanding process that gave him two bottles of water at lunchtime and another at the end of the day.

Seaweed obstacle

As he neared the Caribbean islands, another unexpected challenge slowed him down — Sargassum seaweed. Vast patches of the floating algae forced him to alter his course to keep it from tangling in his rudder. At one point, he found himself trapped in a dense patch the size of two football fields, struggling to navigate through the thick mass.

Despite everything, Derreumaux has stayed remarkably upbeat. Listening to music every day and getting short updates from his brother about life at home have kept him feeling positive through the months of isolation.

During the final two days of his paddle, the current pushed him northwest.

"I had to paddle at 240 degrees (which is southwest) to be able to keep going west," he wrote.

Last night, his family boated out to accompany him for the last few kilometers of his journey.

The canoe has always been part of Canada’s national mythology — but it’s a complicated history. For thousands of years, these watercraft provided essential transportation through the vast wilds of North America for the continent’s Indigenous peoples.

Then those same vessels became tools of colonial expansion during the Voyageurs’ fur trade era, displacing native communities and fueling the extraction of natural resources. Finally, it arrives in the modern era, where it’s mostly known for recreational activities “dominated by middle-class white people,” as sports and leisure historian Jessica Dunkin wrote in the 2019 book Symbols of Canada.

That’s quite the circuitous journey — even for a vessel designed specifically for navigating them.

But there’s likely no place on Earth better equipped to tell the canoe’s story than the upgraded Canadian Canoe Museum. Though the museum’s been around for 27 years, it finally raised enough money for a massive expansion last year. It now offers a generous space for paddle lovers, who can explore its collection of 600+ watercraft on a beautiful lakefront property in Ontario.

A uniquely Canadian museum

From the enormous exhibit hall to the hands-on workshops to paddle tours on the water, the museum aims to bring together the canoe’s rich and varied history.

“You can go in one door and paddle out the back. It’s like a family reunion for your boat to be able to go there and see what its parents and grandparents look like,” said James Raffan, a Canadian educator, author, and adventurer. “But it’s not just about celebrating canoes. It’s also about figuring out how to relate better to each other.”

While the U.S. has the soon-to-expand Minnesota Canoe Museum, and the Canoe Heritage Museum in Spooner, Wisc., both are relatively small operations. So the Canadian Canoe Museum provides a represents a unique draw for American tourists with its depth of history and canoe variety.

It also took years to raise $45 million for the museum’s new 65,000-square-foot building, said Megan McShane, communications coordinator for the museum. Donations came in from around the country, with about half the money coming from private foundations and individuals and the other half from various government funding.

Tears of happiness

A long lineage

Not merely a tradition

Paddle tours & workshops

Upcoming events

This article first appeared on GearJunkie.

A young Venezuelan packrafter briefly became a modern-day Jonah and Pinocchio when he found himself inside the mouth of a humpback whale. The whale released Adrian Simancas unharmed, and his father, Dall Simancas, caught the entire bizarre incident on video.

Adrian Simancas, 23, and his father Dall, 49, were packrafting through the Strait of Magellan between Tierra del Fuego and mainland South America. Dall, who’d been filming the waves, had his camera trained on his son when two massive jaws emerged from the water and closed around the little yellow inflatable and its lone passenger.

For a moment, the choppy waters are empty, with man, beast, and boat submerged beneath the waves. Then, Adrian reemerges, followed by the packraft, which he quickly swims for. A massive grey, finned back crests briefly beside him and then is gone.

Amazed at his lucky escape, Adrian later described his experience. The inside of the whale’s mouth, he said, was slimy against his face, and all he saw was dark blue and white. He thought he was going to die -- and then he was on the surface again, pulled up by his life vest.

Not technically swallowed

Despite thousands of years of mythology, it is not actually possible for a person to find themselves in the stomach of a whale.

"Ultimately, the whale spit out the kayak because it was physically impossible to swallow," said Brazilian conservationist Roched Jacobson Seba.

Despite their massive size, whales have very narrow throats, about the width of a human fist. They can stretch to be a bit larger, up to about 38cm, but a boat and its passenger are quite beyond their capabilities.

Only one whale can theoretically swallow a human. The sperm whale has sharp teeth and feeds on large squids and fish. This means it has a large enough esophagus to gulp down a human. Encounters with them are much rarer, though, and sperm whales have not swallowed any humans except in fiction. The leviathan in Moby Dick that nipped off Captain Ahab's leg was a sperm whale.

Being engulfed in the massive mouth of a humpback, however, is not off the table, as Simancas learned. He isn’t the first person to spend time in the slimy maw of a whale. In 2021, a humpback 'swallowed' lobster diver Michael Packard off Cape Cod. Like Simancas, he was soon spat back out. Californian kayakers in 2020 and a tour operator off South Africa’s Port Elizabeth in 2019 reported similar incidents. This even once happened to a confused harbor seal.

Probably unintentional

Researchers have weighed in on these engulfing incidents. They insist that the whales did not intend to have people in their mouths any more than the people intended to be there.

As baleen whales, humpbacks take in huge gulps of seawater. Then they use the bristles in their mouths to filter for plankton, shrimp, and small fish. This is what they are after, and the rest, like paddlers, they soundly reject. When you are as big as a whale and maybe not paying attention, you can accidentally gulp down Adrian Simancas and his packraft along with your seawater and shrimps.

Accidents like these are why whale researchers warn people not to use silent craft, like kayaks and paddleboards, in waters where whales are active. Whale-watching boats keep their engines on at all times to alert the whales to their presence.

Adrian Simancas and his father don’t hold a grudge against the whale. At first, terrified, Adrian thought an orca was eating him. However, after he got free, he realized that the whale was probably “just curious.” Father and son said they plan to get back in the water soon, despite the engulfing.

If there’s one attitude that’s nearly universal among adventure athletes, it’s a pathological commitment to optimism. Johnny Coyne and Liam Cotter of Ireland possess this quality in spades. In the last five months, they’ve camped in freezing cold temperatures beneath the cliffs of Dover, hauled loaded kayaks uphill for 160km through Germany’s Black Forest, and when they knocked a hole through one of their boats in a French canal, they went door to door asking for help to repair it.

To these many obstacles, Coyne merely says, “It’s all part of the experience.”

The two 24-year-olds set out from Ireland in early September 2024 to pull off an improbable quest: kayaking across Europe from Dublin to Istanbul. That could make them the first people in the world to travel the continent by kayak. It hasn’t been easy, and several setbacks have added months to the planned itinerary.

Recently, Coyne and Cotter were happily setting up camp along the Danube River, near Germany’s border with Austria. Of the 5,000 total kilometers likely required to reach Istanbul, the pair have traveled more than 1,900. They’ll now follow the Danube through Eastern Europe until it empties into the Black Sea, where they’ll follow the coastline all the way to Istanbul.

“I know this is going to be one of the longest and most unique journeys I’ll ever do,” Coyne said. “Trying to stay in the present moment is key.”

Channels and canals

While Coyne’s kayaking quest has been more difficult than he expected, it’s far from his first grand adventure. The young Irishman has committed himself to daring outdoor journeys in the last few years, from cycling to Portugal and trekking across Nepal to a bike trip from Canada to Costa Rica.

Though neither consider themselves serious kayakers, Coyne and Cotter compensate for the lack of experience with an indefatigable attitude.

“I didn’t have too many expectations of the journey. I just knew it was gonna be hard,” Coyne said.

It’s possible that the most difficult parts of the trip are already behind them. For starters, it took them nine long hours of paddling to make an unsupported crossing of the Irish Sea to England. They arrived at 10 pm, slept for a few hours beneath the famous White Cliffs of Dover, and then woke up at 4 am to start their crossing of the English Channel.

Though they’d planned on having a support boat for some extra protection while crossing one of the business shipping lanes in the world, the operator canceled at the last minute. So Coyne and Cotter once again paddled unsupported, pulling off a 12-hour crossing while fighting the channel’s fierce winds and waves.

Riverbank serendipity

Portaging through Europe

The kindness of strangers

Halfway there

This article first appeared on GearJunkie.

Sea kayaker Cyril Derreumaux has started paddling across the Atlantic Ocean. He pushed off from La Restinga in the Canary Islands this morning and will travel 4,800km alone to Martinique.

Derreumaux, 46, had planned to leave on December 17, but a gale pushed that back twice. He finally left today.

While rowing the oceans has become popular, thanks to annual races across the Atlantic and Pacific, only a handful of people have successfully kayaked the Atlantic. Derreumaux wants to add his name to that very short list.

He hopes to finish in 75 days but estimates that the crossing will take between 70 and 90 days, depending on what the ocean throws at him.

Pacific prelude

Two years ago, he kayaked across the Pacific from California to Hawaii. What he thought would be a 70-day journey took 91 days. This 2022 Pacific paddle, Derreumaux's first big journey, was inspired by Ed Gillet’s legendary 1987 crossing. The route Derreumaux took was identical, but the experience was quite different. Gillet used an off-the-shelf Tofino double kayak, an SOS transmitter, and a radio, while Derreumaux had a self-righting, state-of-the-art vessel that was built with an ocean crossing in mind.

Derreumaux doesn’t think anyone will ever recreate Gillet’s journey. He describes Gillet as a trailblazer and a maverick. Speaking to ExplorersWeb after his first ocean crossing, he said, “He inspired me, and I’ve been in touch with him many times. The way he did it, sleeping in the cockpit with a tarp over himself, navigating with a sextant and no communication whatsoever, he was truly solo. I was solo because I was alone in the boat, but I had land support. I could text back and forth and even make a phone call when I had issues. He’ll never be reproduced.”

Custom-built kayak

The French-born explorer will once again complete his journey in Valentine, the seven-meter vessel that carried him across the Pacific. Fully loaded, it weighs 370 kilograms. It does not resemble a traditional kayak. It has an enclosed cabin for sleeping, solar panels, an external antenna for making phone calls to his land team, and a pedal system. This means that besides paddling, Derreumaux can pedal to propel himself forward. This will allow him to use different muscle groups on the lengthy crossing.

He expects the first two weeks to be the most challenging. He will have to contend with seasickness, sleep deprivation, and adjusting to paddling for such extended periods.

Derreumaux plans to follow the routine that worked for him on the Pacific. Starting at sunrise, he will paddle for five hours, then stop to eat, and do another five-hour stint. He will try to get a few more hours in if conditions are good. Throughout the night, he will wake up every two hours to check on the boat and its position.

You can follow his progress here.

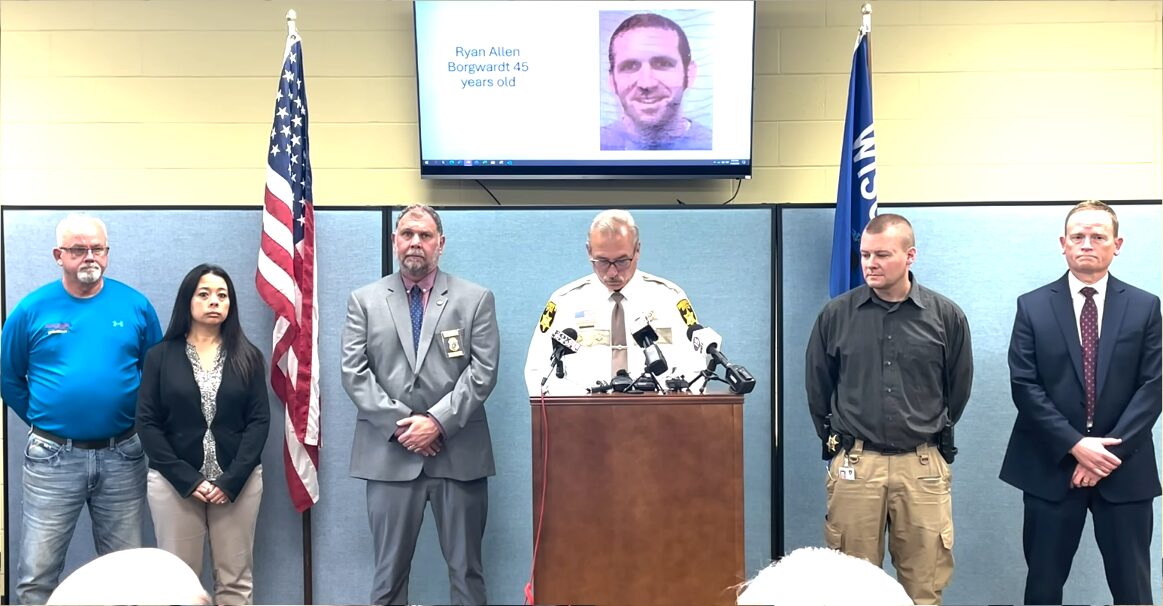

The missing kayaker who faked his own death and fled to Eastern Europe has returned to his home state and turned himself in.

On Tuesday, December 10, 45-year-old father Ryan Borgwardt returned to Wisconsin from the Eastern European nation of Georgia. There, he surrendered himself to the Green County Sheriff's Office. The next day in court, he was charged with obstructing an officer. He was then released on a $500 bond after entering a not guilty plea.

Now, with Ryan Borgwardt back in the States and in open communication with authorities, his strange journey can begin to be untangled.

The 'drowning'

Borgwardt had allegedly planned his "accident" for some time. On August 11, he went up to Green Lake, which he chose, he told authorities, because it was the deepest lake in the state.

Once there, he packed his vehicle, carefully pulling it all the way up to the doors of his shop to avoid security cameras. He loaded it with an e-bike and inflatable raft he had bought secretly, as well as his kayak. On the way up, he stopped and bought a hat and backpack from Walmart.

The complaint alleges that he stashed the bike and new backpack in a patch of trees and set out onto the lake in his kayak, making his way toward what he believed to be the deepest section. Borgwardt transferred to the inflatable raft and began throwing things into the lake: first his phone, then his wallet, keys, life jacket, fishing pole and tackle box. Finally he flipped the kayak so it would appear to have capsized and returned to shore in the inflatable.

The escape

Having faked his death, he now had to flee the country. For this, Borgwardt retrieved the e-bike and rode through the night, covering the 110km of backroads to Madison, Wisconsin. Having packed a spare charged battery, he was able to go all night without stopping. In Madison, he hid the bike, raft, and some personal belongings in a local park and boarded a Greyhound bus to Chicago, Detroit, and finally the Canadian border.

Borgwardt had his passport, but all other identification sat at the bottom of Green Lake. After some back and forth, Canadian officials let him through.

Once in Canada, he made his way to the Toronto airport and used a Western Union card to get a ticket to Paris.

The long international flight gave him a chance to check for news of his own disappearance. He saw that there was, indeed, news of a missing kayaker. Feeling that his plan had worked, he got off that flight and hopped onto another bound for Georgia.

A former Soviet state, Georgia straddles Eastern Europe and Western Asia. There, Borgwardt met with a woman he’d been in communication with for months. The pair stayed together for several days in a hotel, though he eventually ended up in an apartment.

Putting the pieces together

Weeks passed, and Borgwardt kept checking the news, waiting for the local officials to give him up for dead and call off the search.

But officials were instead growing more suspicious. Everything pointed to drowning -- but why had sonar, drones, and cadaver dogs all failed to find any hint of a body? Their suspicions were further roused when, in early October, they found out that Canadian officials had searched the missing man's name only days after his apparent drowning. This led local police to reach out to Federal authorities.

The story started to come together when officials stopped searching the lake and started searching his laptop. They discovered that he’d been talking to a woman from Uzbekistan and had been researching how to move money into foreign bank accounts. He had even taken out a $375,000 life insurance policy less than a year before.

On November 8, the sheriff, Mark Podoll, announced that Borgwardt had likely faked his death and fled to somewhere in Eastern Europe. He personally urged the missing man to come home and return to his family.

Borgwardt, shocked, decided to provide authorities with evidence that he was, in fact, alive and well, likely hoping to reassure them and his family without revealing his location. He sent a 25-second video of himself in an apartment.

But authorities did not stop urging him to return, holding another press conference and personal address on November 21 and remaining in contact with the increasingly troubled Borgwardt.

Return to Wisconsin

Finally, Borgwardt folded under the pressure and guilt being applied by authorities. He returned on his own accord, without extradition. Now that he has done so, however, the authorities who begged him to return are seeking restitution.

The Green Lake sheriff's office alone spent at least $35,000 on the search. Borgwardt, who could not afford a lawyer, may be compelled to repay part of this cost. The misdemeanor crime he was charged with carries a maximum penalty of nine months in jail and a $10,000 fine.

It remains to be seen how this bizarre case, which began as a wilderness search-and-rescue and is now a court drama, will ultimately end. Sheriff Podoll, however, is happy with what they’ve done.

“What better gift could he give his kids than to be there for Christmas?" Podoll said. “We brought a dad back.”

Erik Boomer and Ben Stooksberry are two of the best expedition kayakers in the world. But even they may have met their match when they travel to Chihuahua, in northern Mexico. The plan? First descents on the rivers that rampage through the region's famously beautiful (and dangerous) canyons.

¡Ay Chihuahua! is the 17-minute film the pair created about the expedition. The story unwinds as a good old-fashioned travel tale. After laying out the broad strokes of the expedition, we meet members of the Group of Speleology and Exploration Cuauhtémoc, a collective of Mexican canyon explorers. They chuckle ruefully when the kayakers ask them if the rivers they've targeted are runnable.

Dangerous and hard

"I think it's dangerous and hard," Ricardo Rios, one of the group's members, says.

But before the duo can get on the water, they have to wait out agonizing days of nonstop rain, which swells their initial objective — Rio Candameña — well past runnable levels. You can see Boomer and Stooksberry's frustration as they huddle under eaves and watch the water pour. Doubt starts to creep in.

"We are teeter-tottering between total stoke to drop into these rivers, and then when the rivers flash flood, we're scared and kind of wondering what the hell we're doing here," Boomer says.

But these are seasoned expedition kayakers, and they know that waiting — and the hesitation that accompanies it — is part of the job.

"In my experience, any worthy or difficult or challenging objective is just this mind game," Stookesberry says.

The kayaking starts in earnest about six minutes into the film. The kayakers change tacks while they wait for the Candameña's waters to recede, deciding to tackle a first descent of the nearby Río Concheño.

Boxed-out canyons

Kayaking awesomeness ensues. The boys scout when they can, but it's a long trip, and they have another river on their mind. Time is of the essence.

"Gnarly, boxed out barranca canyons that were just enough to make everything scary," Boomer notes of the river. "So you think to yourself you're going to go here, and here, and then go left. And then when you get into the canyon..." he finishes before trailing off ominously.

After several exciting kayaking sequences that will appeal to experts and neophytes alike, Boomer and Stookesberry finish their run in the small town of Moris. There, they party with locals before traveling back to the Candameña, whose waters are now at perfect levels.

Well. Perfect for the Candameña. There's a reason nobody else has notched a first descent on it. The pair probably spend more time portaging than they do kayaking. But when they do get to drop into whitewater, it's all adrenaline. The drops are steep, and the moves are must-makes.

"It's a marathon of Class V, a marathon of portaging, a marathon of intensity. And there just isn't one moment that you can pick out, except maybe the moment when things go bad." Stooksberry says.

The moment he's referencing occurs when Boomer puts a sizable dent in the bow of his kayak, then pokes a hole through it while attempting to repair it over an open fire.

In the end, the pair achieve their first descent and are all the better for it. "We didn't get held hostage. The people didn't threaten us. Nobody almost died. We don't hate each other. Maybe it's kind of a boring story," Stookesberry says.

Reader, trust me on this. It's anything but.

When you combine funding from Red Bull, a legendary exploratory kayaker, a world-class photographer, a tight group of the very best whitewater paddlers on the planet, one of the top storytellers in kayaking, and a remote, little-explored river in Africa, you get one epic adventure.

This adventure is showcased in the free online film Gabon Uncharted: Sending Ivindo Falls. And, you’re going to want to watch it!

Kayaking the Ivindo River

On the equator, along the west coast of Africa, lies the country of Gabon. Cutting across the country is the Ivindo River, a remote high-volume waterway deep in the jungle.

It was first explored by whitewater kayak by Olaf Obsommer and team in 2007. Obsommer returned in 2024 to help guide the SEND collective team down this mighty river.

The four-person SEND team consisted of Adrian Mattern, Dane Jackson, Bren Orton (R.I.P.), and Kalob Grady. These are some of the very best whitewater paddlers in the world today, likely ever, and also a group of very close friends.

Much of the Ivindo’s mighty rapids were portaged around during the 2007 expedition, as little was known about the area and the dense jungle made scouting difficult. Modern technology, in the form of satellite imagery and video drones, has opened up all-new ways to scout a river safely and quickly.

Mattern has been dreaming up a trip to tackle the Ivindo’s rapids since he saw pictures of Obsommer’s group on the river. He planned the 10-12-day and 150km river expedition, and led the group.

Gabon Uncharted: Sending Ivindo Falls

This article first appeared on GearJunkie.

BY JUAN HERNANDEZ

Ryan Borgwardt was reported missing on August 12 in Green Lake, Wisconsin. His wife was the last person to hear from him. The evening before, he texted her to say he was kayaking to shore.

When the 45-year-old father of three failed to return home by morning, she let local authorities know. A week later, police reported they had found his kayak capsized in the lake and a tackle box containing his wallet, keys, and driver’s license. They spent the next 54 days searching the lake with the help of the non-profit search organization, Bruce’s Legacy, without finding Borgwardt.

“Keith Cormican, [who leads] Bruce’s Legacy, sifted through hours and hours of sonar data and images,” Green Lake County Sheriff Mark Podoll said. “Keith’s expertise and equipment led us to believe either something very odd occurred and Ryan was outside the area that had been searched, or something else had occurred.”

Nearly three months since Borgwardt’s disappearance, the Green Lake sheriff’s department still hasn’t found a body after searching every corner of the lake. Instead, they believe Borgwardt staged the entire thing and fled the country.

Shocking news

Sheriff Podoll held a press conference last week to lay out the investigation's findings, including the shocking news that Borgwardt may have faked the entire thing. A turning point in the investigation came in early October when they learned that Canadian border authorities had actually checked Borgwardt’s name the day after he’d gone missing. More evidence started to pile up after that major discovery.

For example, he erased everything on his laptop’s hard drive just after syncing all of the contents to the cloud on August 11. He’d also taken out a $375,000 life insurance policy months before the disappearance and transferred funds into a foreign bank. Authorities also say they’ve traced communication between Borgwardt and a woman in Uzbekistan.

What was a major search-and-rescue operation for a missing kayaker has turned into a criminal investigation with several departments, including the FBI. A press release from the Green Lake County Sheriff’s Department didn’t lay out specific charges that could be applied, but they are looking into any people who could have knowingly helped the father of three plan his disappearance.

“At this time, we believe that Ryan is alive and likely in Eastern Europe,” Sheriff Podell said.

This article originally appeared on The Inertia.

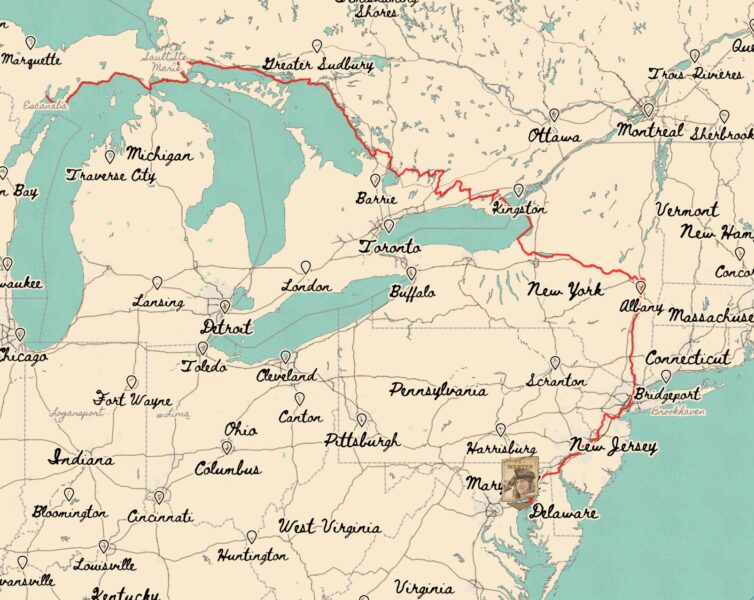

Peter Frank is spending the next year canoeing what's called the Great Loop around the eastern United States and part of Canada. The 9,700km circuit, normally done by motorized craft, takes in the Great Lakes, the Mississippi River, the Gulf of Mexico, and the Atlantic coast, among other water bodies.

The 23-year-old began in June and is going solo and in a clockwise direction -- the opposite to almost everyone else. This forces him to paddle upstream for over a quarter of the journey.

He is following in the footsteps of the man who made his canoe in the 1970s -- Verlen Kruger. Kruger did two of the longest canoe journeys ever -- the 29,341km Two Continent Canoe Expedition from the Arctic Ocean to Cape Horn and the 45,130km Ultimate Canoe Challenge through interior and exterior North America.

Why clockwise?

Frank is attempting to replicate the Great Loop part of Kruger's route. Frank believes that Kruger and partner Steve Landick are the only canoeists to have paddled it clockwise. He wants to see if it can still be done.

Frank expects the journey to take him another six months. Starting on Lake Michigan, he paddled through the Great Lakes, the Erie Canal, and along the Hudson River. After 2,380km, he reached the Chesapeake and Delaware Canal and is now in Chesapeake Bay.

From here, he will head to the Intracoastal Waterway and along the country's East Coast to Florida, the Mississippi River, and back north.

He paddles six to 10 hours a day and carries his tent and supplies in his canoe, which looks a bit like a kayak but is propelled by a single-bladed paddle. For food, along with dehydrated meat and potatoes, he picks up fresh food whenever he can.

While he camps most of the time, occasionally someone will offer him a bed and warm shower.

Past adventures

This is not his first solo long-distance challenge. In 2021, after three years of planning, he unicycled 3,800km from Wisconsin to Arizona. In 2022, he spent five months paddling the Mississippi River. Then he biked through Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, and Florida, then circumnavigated Florida by canoe.

From a young age, Frank knew he did not want a traditional life. At the age of 14, he was hiding in a leaf pile, about to jump out and scare one of his friends, when a car ran over him. It shattered his spine and left him nearly paralyzed. His unicycle expedition raised funds for the organization that aided his recovery. That launched him into this world of adventure.

You can follow his journey here.

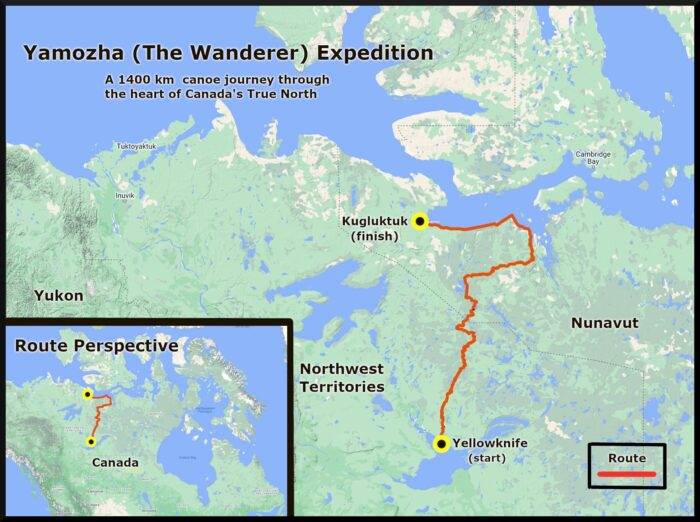

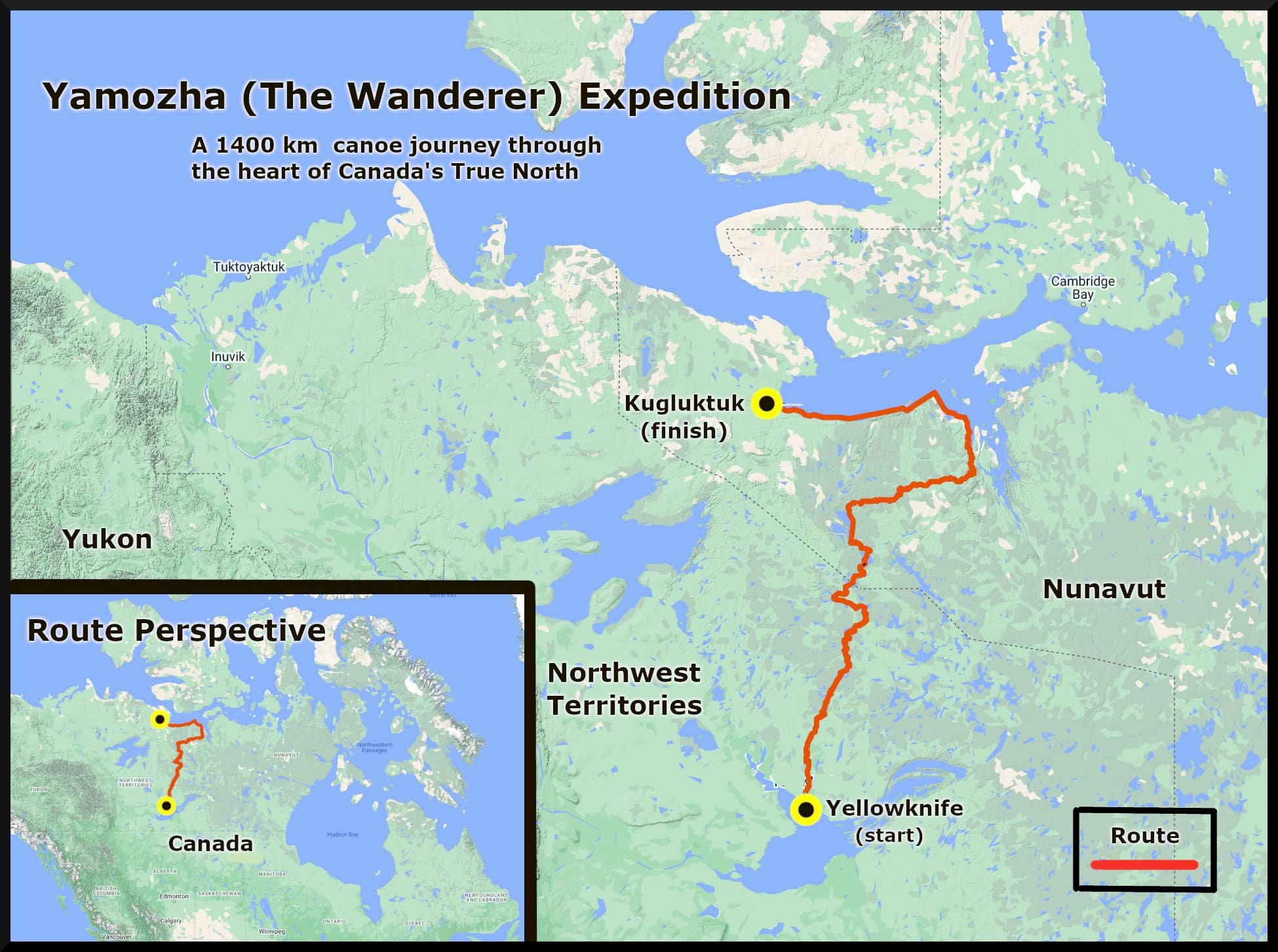

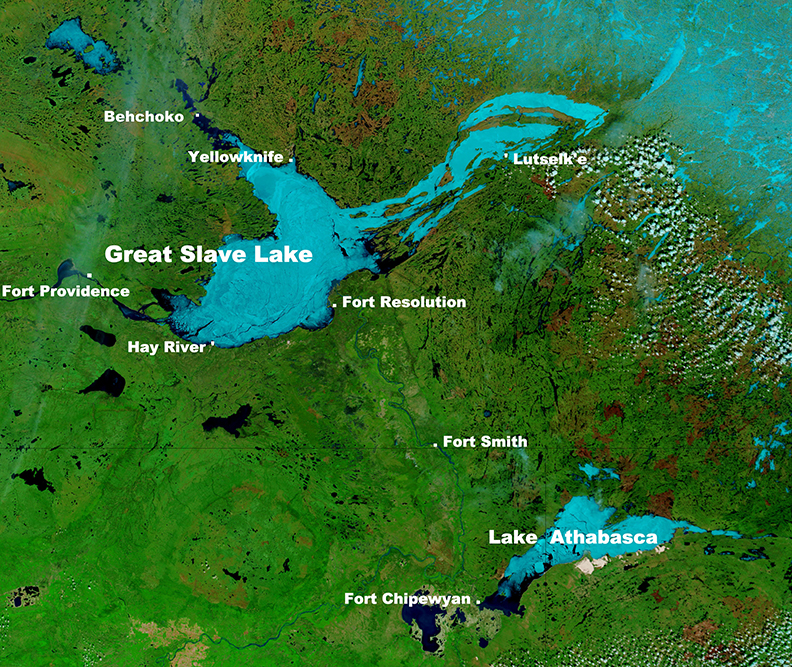

Adventurer Frank Wolf sure had an eventful year. The Canadian completed a 500km kayak expedition around the Darian Gap, notched a 325km ski trip on Baffin Island, and — most recently — traveled 1,350km by canoe from Yellowknife to Kugluktuk.

Wolf completed that last adventure earlier this year in a brisk 36 days, which is handy. With just 38 days of supplies, he and partner Arturo Simondetti had very little leeway.

The pair battled currents, winds, rapids, and long portages, especially during the first half of the expedition.

More rock than water

"A lot of places that looked like rivers on the map were just rock," Wolf told ExplorersWeb. "So we ended up doing a lot of two-kilometer portages where we thought we would be paddling."

Wolf's expedition style is to pick a destination and do his research but not get overly bogged down in minutia, like specific distance goals or pre-chosen campsites. He simply presses on, and if he gets behind schedule, as he did here, he presses harder.

Early in the trip, Wolf and Simondetti were so behind that they thought they might have to bail. But they buckled down and persevered through long days in rough conditions.

"[Once], we put in a 16-hour day, like 76km, on the ocean, in a canoe," Wolf said of the kind of effort it took to make up lost time. "So we ground and just kind of came in at the last."

As for Simondetti, he had little to no canoe experience before setting off with Wolf. When Wolf isn't adventuring, making films, or writing, he's demolishing derelict boats -- that's what he does for a living. Wolf met Simondetti during this work. Despite the differences in age and experience (Wolf is 54, Simondetti 24), Wolf recognized a fellow adventurer.

"He's a smart guy, and he's calm under pressure," Wolf said of his partner. "I had a few other people turn me down [for the trip] before a lightbulb went off, and I went, 'Oh yeah, what about Arturo?' He's a capable guy who I knew could pick it up quickly and grind when needed."

Animal encounters

And partner is the optimal word. According to Wolf, it wasn't a mentor/mentee relationship. But the younger man still had plenty of eye-opening experiences. In one notable vignette, a decidedly unshy grizzly wandered up on the two in the middle of a portage.

And their firearm, brought along expressly to ward off ursine guests, was packed up and out of reach. Some firm calls of "Hey bear!" and paddle clacking managed to drive the curious animal away, but it was a tense moment.

"That's when Arturo realized, 'Oh, we could really get eaten out here,'" Wolf said. "Before that, he was just kind of obliviously confident. After that, he was a little more cautious, and we kept the gun on hand just in case we needed it."

Potential bear problems aside, some of Wolf's favorite moments sprung from wildlife encounters. A huge herd of muskox and a dawn meeting with a wolf were particularly memorable. The human Wolf had just finished his morning business when the animal came sniffing around, eventually rolling in Wolf's excrement before trotting off, presumably to transmit whatever information that act gathered to his buddies elsewhere.

Mental and physical trials

As Wolf pointed out in his chat with ExWeb, the adventures he undertakes require both physical and mental fortitude. Injuries were minor, aside from a knee tweak incurred by Simondetti while hauling a heavy pack. Simondetti is a skateboarder and skier when he isn't adventuring, so he was able to self-diagnose the wound as non-trip-ending. After a few days of hobbling, he was good as new. Plus, he had a secret weapon on his side.

"He's a young fella," Wolf said with a laugh.