BY WILL BRENDZA

Texas is getting its very own long-distance cross-state thru trail thanks to one ambitious outdoorsman with a vision. The Cross Texas Trail (xTx) would extend 1,500 miles from Orange to El Paso, winding along some of the Lone Star State’s most scenic landscapes, passing towns and many historical sites, gaining roughly 56,000 feet in elevation along the way.

The nonprofit organization behind the xTx describes it on its website as “the future Pacific Crest Trail of Texas.”

Veteran trail hiker, bike-riding adventurer, and Texas native Charlie Gandy is leading the charge in establishing the xTx. The former Mesquite and East Dallas resident first had the idea when he was hiking the Tahoe Rim Trail (TRT) in June 2024.

He saw the power that cross-state trails had to connect people, uplift communities, and transform the individuals on them. He was a few days into his hike when it hit him.

“I could see a route across [Texas],” said Gandy. “I just wasn’t sure how I was going to get it done at that point.”

While people could technically hike the route now, Gandy hopes to have it officially established in the near future. At that point, it will be open season for thru-hikers, bikers, and horse riders who want to traverse the state of Texas by trail.

Currently, he’s asking for help from hikers, bikers, and equestrians who can help “ground proof” sections of the trail. Then, in spring 2026, Gandy intends to thru-hike the entire trail himself, and he’s inviting anyone to join him on the adventure.

xTx: The Pacific Crest Trail of Texas

Gandy graduated from the University of Texas and worked under the governor before starting several businesses of his own. He’s a serial entrepreneur, but he also has a history in the nonprofit world. He founded BikeTexas.org, the first statewide bike advocacy group in Texas. Now, he’s also founded xTexas.org.

In his spare time, he’s also an avid and fairly accomplished hiker. “I’ve hiked all of the fourteeners in Colorado and almost all of them in California and elsewhere,” he told me.

He revealed his plans for the xTx at the Texas Trails and Active Transportation Conference in September. He called the initiative kind of a wild ride, but said the response from both the hiking community and most of the locals he’s heard from has been positive.

“This is a big, hairy goal that I get to undertake,” Gandy said. “It kind of has a life of its own.”

The trail will be a mix of singletrack and about 40% gravel roads. It will showcase the diverse environments, scenic landscapes, and cultural variety that span the largest state in the contiguous U.S.

Gandy also hopes the xTx will draw visitors who will bring business to the communities it passes through. “It’s a new opportunity to have a different type of customer in town,” he said.

Crossing Texas: no easy endeavor

xTx Thru-Hike: the route

Miles 0-200

Miles 200-500

Miles 500-1,200

The Home Stretch

Getting xTx Thru-Hike across the finish line

xTx Thru-Hike: regional breakdowns & highlights

Eastern Piney Woods to Hill Country

Ecosystems

Towns

Central Hill Country to Big Bend

Ecosystems

Towns

Western Desert Section & Big Bend

Ecosystems

Towns

What to bring on the xTx Thru-Hike

Hazards on xTx Thru-Hike

Heat & hydration

Snakes & insects

People

This story first appeared on GearJunkie.

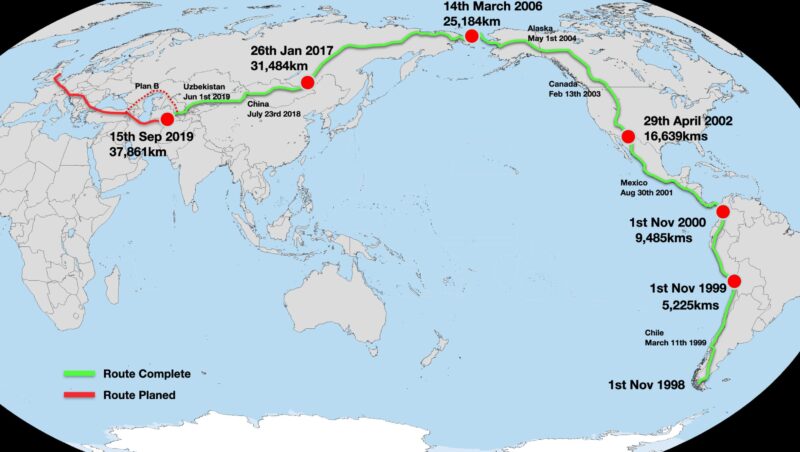

British adventurer Karl Bushby is nearing the end of his extraordinary journey to become the first person to walk an unbroken path around the world. Beginning on November 1, 1998, from the southern tip of Chile, Bushby has trekked over 47,000km across four continents, 25 countries, six deserts, and seven mountain ranges. Now he is starting his final year on the road.

His odyssey, known as the Goliath Expedition, has spanned 26 years, with approximately 13 years spent actively walking and the remainder consumed by bureaucratic challenges, pandemics, visa restrictions, and financial difficulties.

Two rules

Bushby has two self-imposed rules: he cannot use any form of transportation on his route, and is not allowed to go home until he is finished. Logistical problems have occasionally forced him to put his trek on hold for up to three years and fly to Mexico or elsewhere to cool his heels. But always, he picked up where he had left off and did not use anything but his two feet on the route itself.

His path took him through multiple conflict zones, including the infamous Darien Gap between Colombia and Panama. Crossing the 320km stretch of jungle took him two months and included an 18-day detention in Panama before he was allowed to proceed.

Continuing northward, Bushby crossed Central America and entered the United States in 2002, eventually reaching Alaska in 2005. In March 2006, he achieved a significant milestone by crossing the Bering Strait on foot with French adventurer Dimitri Kieffer. The duo spent 14 days navigating a frozen 241km section to cross into Siberia, a supremely difficult task over broken, swiftly moving ice. Here, Russian border authorities detained them for not entering at an official port.

Difficulties in Russia

Bushby's progress through Russia was slow due to visa restrictions. He had to leave the country every 90 days, since his tourist visa only allowed him to stay in Russia for 90 days of every 180 days.

In 2008, his journey came to a standstill. He lost sponsorship for a few years and could not travel to Russia, so he set up camp in Mexico until he found more funding. In 2011, he resumed his trek, once again in 90-day stints. Then in 2012, he was denied a further visa, and in 2013, he received a five-year entry ban from Russia.

Determined to continue, Bushby headed to the U.S. and walked 4,800 km from Los Angeles to the Russian Embassy in Washington, D.C., to protest the decision. His efforts weren’t wasted. In 2014, the ban was lifted, and he once again found himself in Russia. From there, he continued through Mongolia, where he joined with other adventurers (including Angela Maxwell, also on a solo walk around the world) to trek across the Gobi Desert with camels.

After 1,130km, several disagreements fractured the group, and Busby continued into China by himself. In 2018, he crossed Kazakhstan and then made his way through Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan. Here, his journey came to a premature halt when he could not secure a visa to his next country, Iran. The pandemic also set in around this time. He once again retreated to Mexico.

An odd Plan B

In 2022, facing insurmountable obstacles in Iran and Russia, Bushby devised an odd plan B for someone who had spent well over a decade walking. He was going to swim across the Caspian Sea with Angela Maxwell, but even this plan took two years to pull together.

Bushby and Maxwell flew to Bukhara, Uzbekistan, and walked across the Kyzylkum Desert to the Caspian Sea. With limited swimming experience, they embarked on the 288km swim from Kazakhstan to Azerbaijan in October 2024. Over 32 days at sea, they spent 27 days swimming through dangerously rough seas and high winds. Safety boats accompanied them. They swam for three hours in the morning and three hours in the afternoon and slept aboard the boats.

But swimming was not the hardest part of this challenge. Bushby admitted, “I’m definitely not a swimmer, nor do I like swimming.” For both of them, this was completely outside their comfort zone.

For the last six months, Bushby has been picking his way from Azerbaijan to Turkey. Speaking to Turkiye Today, he said, “Other travelers told me Turkey would be one of the most beautiful and welcoming places. And they were absolutely right. People constantly invited me into their homes...The hospitality has been amazing.”

One year more

Now he is just days away from Istanbul and is trying to secure permission to cross the Bosphorus, “It’s only 1.5 kilometers, but it’s symbolic,” he explained. "Crossing it would bring me from Asia into Europe, the final phase of the journey. From there, I’ll walk across Europe and reach the Channel Tunnel in France, eventually walking back home to the UK."

Once he crosses the Bosphorus, he is confident it will only take him one more year to get back to the UK. “It’s been hard being away. And the U.K. has changed so much — I left when Tony Blair was Prime Minister. Since then, we’ve had five or more PMs. I might not even recognize home when I get there.”

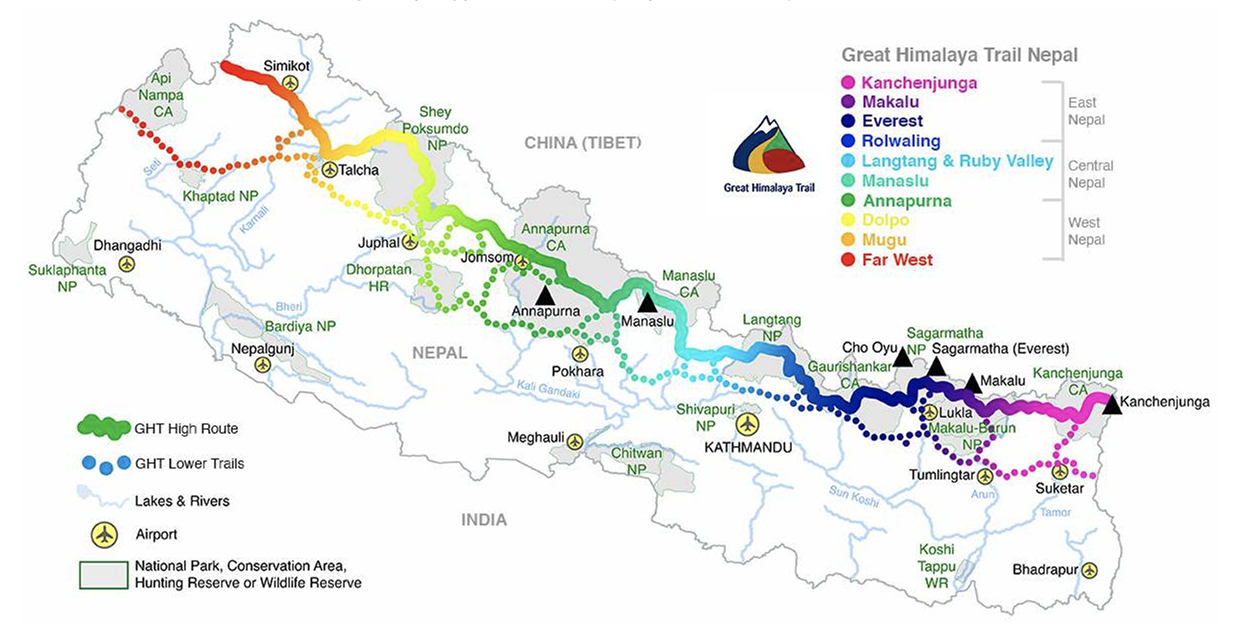

Nepal's Great Himalaya Trail runs 1,750km across the entire country and passes over some of the highest trekking passes in the world. Here in Part II, we examine the route and hear from those who have completed the GHT. You can check out Part I here.

Rolwaling

Tashi Labsta (5,760m) is quite technical and can require fixing ropes. Rockfall can be a problem here. Like Sherpani Col, weather and snow/ice conditions might require a flexible schedule. World Expeditions takes two days on the approach to assess the weather and camp high (5,665m) before the crossing. The pass is close to Thame, roughly 10km away, but 2,500m above the village!

Route finding on both the approach and the pass can be tricky if there’s snow. The “glaciers on the eastern side of the pass are hazardous and crevassed,” Boustead explains on his GHT website. Boustead also notes that food can be hard to come by in Rolwaling, so independent hikers should stock up before the pass.

After the saddle, most trekkers descend to the Trakarding Glacier for a cold night’s camping. Jasmine Star, who hiked half the GHT in 2016 and the other half in 2019, described the descent as the most challenging section.

“It’s hard on the way down," she says. "There are some immense boulder fields after the pass. They go on for like a day, day and a half before you reach a proper trail again.”

The next five to seven days are more relaxed, following rivers and meandering through remote villages in Rolwaling. This section of the GHT finishes at Sano Jynamdan.

Langtang and Ruby Valley

The trail then winds through the villages of Listi, Bagam, Kyangsin, and Dipu. This section is “Nepali flat,” meaning undulating without any big climbs. Then, it’s back to ascending, with a 1,000m+ elevation gain to Kharka and then another 500m to Panch Pokhari at 4,074m.

After a couple more days of gradual ascent, there’s the first high pass in some time. Tilman’s Pass (5,308m) involves some scrambling, and loose rock may cause problems, but it should be doable in a day.

After a night camping just below the pass, the route joins the main Langtang Trail. This means teahouses, relative luxury, and a well-trodden, clearly marked trail. Depending on fitness, speed, and weather conditions so far, hikers can expect to be between 60 and 80 days into the GHT at this point, a little over halfway through.

The next few days are known as the Ganesh link of the GHT, connecting Langtang to the Manaslu and Annapurna regions.

Manaslu and Annapurna

The trail now drops like a stone to 1,503m at the small village of Syabru Besi. The next few days follow a similar pattern. The trail climbs to ridgelines and then descends into valleys and basins (later dipping even lower to 970m), with small villages scattered along the route. This area is the Ruby Valley.

Over several days, you gain altitude again, culminating in a crossing of Larkye La at 5,140m. Along the way, you skirt the edge of the Kutang Himal, a natural barrier that marks the border between Nepal and Tibet. With more elevation, there’s also the return of mountain panoramas, with views of Himalchuli (7,893m), Peak 29 (7,871m), and Manaslu (8,163m). In clear weather, there are good views of Annapurna II (7,937m) from Larkye La.

The trail follows the Marsyangdi River downstream, descending quickly. Leaving Manaslu behind, you enter the Annapurna region. The Annapurna circuit is popular, and the trail is clear, with plenty of places to stay along the route.

You gain altitude again toward Thorong La (5,416m), the highest point in the 300km Annapurna circuit. This pass is a long, arduous day. Tour companies offering Annapurna Circuit treks usually list it as the longest day, with a pre-dawn start to avoid the notorious Thorong winds and 9 to 12 hours of hiking required. It’s not technical, but a long, gradual slog, with several false summits and then a 1,500m descent to Muktinath.

With the Annapurna range now behind you, it’s on to Dolpo.

Dolpo

The Dolpo-pa, a semi-nomadic ethnic group of Tibetan descent, inhabit 24 villages in this region. It’s a remote, rugged bit of the Himalaya with few trees, but the trail is mostly well-marked.

“The GHT provides many variations of ethnicities, religions, and cultures, but the Far West is particularly different,” guide Bir Singh Gurung explained. "Dolpo has its own pre-Buddhist beliefs, such as Animism (Bon) religion and pure Tibetan culture."

Gurung has guided in the Nepalese Himalaya since 1999. He said this was his favorite section of the GHT “because of its remoteness, the wilderness, rich culture, and the landscapes.”

After Muktinath, the trail leads to Kharka, before two sub-5,000m passes bring you to the village of Santa. Another day or two takes you to Lalinawar Khola (river), at the base of 5,550m Jungben La, with great views of Hidden Valley and Dhaulagiri, and 5,120m Niwas La. After quite a few days at lower altitudes, these passes can prove challenging, but both can be completed in around seven hours at a steady pace.

After the passes, the trail descends to another river, Chharka Tulsi Khola. The path flicks between the two sides of the river as you move up the valley. Another high pass rears up ahead, Chan La (5,378m), but it has an easy gradient and is not technical.

Descending to the trading village of Dho Tarap, the trail soon climbs again to Jyanta La (5,100m) en route to Saldang, the administrative center for Upper Dolpo. From there, it’s an easy day to Shey Gompa, an 11th-century Buddhist monastery.

The next two days follow the trail across 5,350m Nagdala Pass to the famously beautiful Phoksundo Lake.

The Far West: Rara Lake & Yari Valley

From Phoksundo Lake, you enter Nepal’s Far West, the least visited region in the country and the final segment of the GHT.

Crossing Kagmara La (5,115m) is a long, two-day effort, but the next five or six days are fairly easy. The trail drops and winds through a few villages on the way to Rara National Park and Rara Lake, the largest lake in Nepal.

Depending on your pace (and your start date), the monsoon rains could begin around this time. If so, expect heavy deluges, muddy boots, and leeches.

From Rara Lake, there are two GHT options: From Gamgadhi to Simikot and the Yari Valley, or cross-country to Kolti and Chainpur and on to the Mahakali Nadi River in India. World Expeditions elects to take clients on the Gamgadhi to Simikot and Yari option because “this route travels closer to the center of the Great Himalaya Range.” But independent trekkers will find either route interesting and little visited.

Assuming you take the “upper” route, you leave Rara Lake for Karnali. Following a familiar pattern for the next week, you climb over ridges and then descend into basins and valleys, never surpassing 4,000m and sometimes dropping below 2,000m. At Shinjungma, the main trail branches away, heading further north toward the border with Tibet. It eventually finishes at the town of Hilsa.

How long does it take?

Finishing times vary considerably. The Great Himalaya Trail website suggests 120-140 days, World Expeditions schedules 150 days (including getting to and from start and end points), and some speedy independent travelers knock it over in around 100 days.

Difficulty, fitness, and training

World Expeditions rates the GHT a 9/10 on their difficulty scale (the highest rating of any of their treks), grading it as an intermediate mountaineering expedition. While they don’t require mountaineering knowledge, they do check fitness levels and previous hiking experience when people wish to sign up.

Heather Hawkins completed the GHT (guided and supported by World Expeditions) with her adult children. Heather is a marathon runner, and she describes the whole family as having a good fitness foundation, with plenty of hiking and bushwalking under their belts. Only her son had climbing experience, but the tour company provided training with jumars, crampons, and using fixed ropes before they hit stage two of the GHT and the high, technical passes.

“We were with climbing sherpas, and I felt very safe and well looked after,” Hawkins said.

Likewise, Jasmine Star (also guided and supported) had great base fitness before taking on the GHT. She had previously finished Bhutan’s famous Snowman Trek and had some mountaineering experience. Star managed a mountaineering lodge on Mount Hood in the 1990s and had previously climbed Mount Rainier.

“The eastern half is very hard because of all the snow,” Star said. "Sleeping, walking in snow, snow on high passes. It’s draining. The West is easier. We had three people start on the full traverse [from east to west], and one asked to be evacuated by helicopter after 27 days, which was very tricky. Different people joined for various sections of the traverse, including six people for stage two. Some suffered altitude sickness and quit to hike out to Lukla after Amphu Labsta.”

Stage two (Makalu & Everest) is the consensus crux of the route. Professional guide Soren Kruse-Ledet trekked most of the route in 1998, but from Mount Kailash in Tibet to Kangchenjunga in Eastern Nepal, and now guides sections of the GHT.

“Stage two is the most challenging as it includes Sherpani Col and West Col,” Kruse-Ledet said. "Both of them are over 6,100m, plus an additional three passes over 5,000m. It’s high altitude, remote, and technical."

He went on: "I have had situations where clients or staff have experienced altitude sickness, which can have quite a sudden onset. We’re trained and prepared to manage these situations, but we are keenly aware of the risks. But, while challenging, it is also exceptionally beautiful. You experience views of Everest and Makalu in a part of the Himalaya that doesn’t see many other travelers."

Kruse-Ledet doesn’t think the GHT is beyond most fit, outdoor people.

“I think it’s challenging because of the length of time that you’re on the route. The difficulty is not necessarily the physical aspect but the psychological challenge of having to walk nearly every day for five months. Overall, I would describe this as a difficult trek for committed and experienced walkers.”

Guide Bir Singh Gurung concurs: “Mental and physical fitness is necessary. Socially [it is different], it is a diet you are not familiar with, and comfort levels are different. You need great willpower and determination. Experienced trekkers with basic mountaineering skills are ideal.”

Vince Gayman completed the GHT guided and supported in 2018.

“I had limited mountaineering experience,” Gayman said. "I had done some glacier travel with crampons and had climbed a couple of our local peaks with ropes and an ice axe, but nothing very extensive. For someone with no experience and traveling without guides, [stage two] would be VERY challenging."

Independent vs. guided

There are several things to consider when choosing between independent and guided GHT hikes. The first may be cost.

Boustead estimates costs for independent trekkers as follows:

Go solo as much as possible: $13,500

Twin-share with minimum guiding: $7,250 per person

Solo “as much as possible” is key. Restricted Area Permits (RAPs) are required for some areas. These are for a minimum of two foreigners (making a true solo journey considerably more expensive) and require a local guide. Those completely adverse to a guide reportedly hire one to pass certain checkpoints and then release them in between. Please note that we are not advising people to do this.

At the time of writing, RAPs are required for 15 areas of Nepal: Upper Mustang, Upper Dolpo, Lower Dolpo, Tsum Valley, Manaslu Areas, Gosaikunda Municipality, Nar and Phu Trek, Khumbu Pasang Lahmu Rural Municipality Ward Five, Humla, Taplejung, Dolakha, Darchula, Sankhuwasabha, Bajhang, and Mugu.

Guided tours are, of course, much more expensive. Tour companies charge $25,000-$30,000 for a fully supported traverse (including guides, porters, accommodation, food, permits, and transport to and from the GHT).

Other things to consider include how much gear you want to/can carry, your tolerance for complex logistical planning (where to stay, how much money to carry, what permits you need, etc.), your desired pace, your fitness/alpine experience, and your route-finding abilities, particularly on the high passes and if the weather is poor.

Pace might seem a minor consideration, but larger groups move much slower, and for the speediest independent hikers, even a single guide can prove a drag.

“Some of the high passes require a fixed rope for safety,” Gayman explained. "This makes for slow going, especially with a large team carrying lots of gear. Needless to say, there is quite a bit of stop-and-go to keep everyone safe. For us, the weather was amazingly good and the views spectacular, so the pace wasn’t a problem.

Thru-hiking is a distinctly American term, but long-distance hiking routes aren’t limited to North America. The Great Himalaya Trail (GHT) might eventually encompass a continuous route through Bhutan, Nepal, and India. But for now, the Nepali GHT already offers an almighty 1,750km journey across the entire country and passes over some of the highest trekking passes in the world. Here, we examine the route and hear from those who have completed or guided the GHT.

History of the GHT

Hiking long-distance across the Nepali Himalaya is not new. Locals have covered vast distances since time immemorial, and foreign hikers have completed traverses starting in at least the 1980s.

Notable early long-distance hikers included Peter Hilary (son of Edmund Hilary) Chhewang Tashi, and Graeme Dingle walking from Sikkim, India, to the K2 Base Camp in the Karakorum in 1981, and Hugh Swift and Arlene Blum's nine-month traverse from Bhutan to Ladakh, India between 1981 and 1982.

More recently, in 1997, Frenchmen Alexandre Poussin and Sylvain Tesson hiked an impressive 5,000km in six months, from Bhutan to Tajikistan.

There have been numerous runners who’ve tackled large distances, too. Richard and Adrian Crane ran from Kanchenjunga to Nanga Parbat in 1983 and in 2023 Rosie Swale-Pope ran 1,700km across Nepal. But both of these trips deviated a long way from what is now the GHT. Swale-Pope ran in Nepal’s mid-hills, and the Crane brothers went far enough south to cross into India.

The modern GHT is a relatively new concept. Between 2008 and 2009, Robin Boustead traced a path over 162 days, linking trekking sections that became the most commonly used route.

The high route

There’s both a high and a low route through Nepal. Hikers can easily switch between them, depending on the weather and their tolerance for high-altitude passes. Often you can adapt the route to suit you. This is a network of trails rather than a singular route. But here, we’ll concentrate on one version of the high route.

Most trekking companies divide the route into three regions, East, Central, and West Nepal, and seven (or more) stages: Kangchenjunga, Makalu & Everest, Rolwaling, Langtang & Ruby Valley Link, Manaslu & Annapurna, Dolpo, and finally Nepal’s far west, Rara Lake and Yari Valley.

Hikers tend to start in the east in early March. This is a couple of weeks earlier than the typical trekking season, and it will still be cold with plenty of snow, making for a tough start.

But there is a good reason to start so early. Hikers need to complete the highest passes before the monsoon rains arrive in mid-June. This is also why most people start in the east rather than the west. The GHT’s highest, most difficult passes are bunched in the east and would potentially be more dangerous later in the year.

East Nepal: Kanchenjunga

It’s quite the slog just to get to the eastern starting point of the GHT, though it won’t tax your legs. From Kathmandu, you fly to Bhadrapur, tucked into the far south-eastern corner of Nepal on the border with West Bengal, India. From there, it’s a long drive as far north as the roads will take you to Chiruwa. The drive usually takes two long days.

After Chiruwa, you’re on foot, continuing north, parallel with the Indian border, toward Kangchenjunga in Nepal’s northeast. You start low, at around 1,600m, acclimatizing gradually as you push north. Three to four days of hiking brings you to Ghunsa (3,430m), the last village in the area that is inhabited year-round.

Over the next three days, hikers ascend quickly, climbing scree and lateral moraine to Kangchenjunga Base Camp at 5,143m. This marks the furthest east you’ll travel. Hikers then retrace their steps back to Ghunsa before the first pass of the GHT: Nango La.

At “only” 4,776m, Nango La is not terribly high, but this early in the season, it can still be tricky, with deep snow. Once over the pass, you drop over 1,000m, heading to the village of Olangchung Gola. It’s possible to do the pass and reach Olangchung Gola in one extremely long day, but most hikers choose to find a camping spot once they’ve descended the pass.

Makalu and Everest, the crux

Another reasonably complex pass, Lumbha Sambha, follows Olangchung Gola. Most people camp at a “base camp” and leave before dawn the next morning to cross the saddle of the pass at 5,160m. Expect deep snow and spectacular views of Makalu to the west and Kangchenjunga and Jannu to the east.

Once down from the pass, you’ll hike at a lower altitude for the next few days before gradually climbing toward Makalu Base Camp at 4,870m. From there, it is on to Swiss Base Camp at 5,150m.

Next comes the crux of the entire traverse: Sherpani Col and West Col.

This crossing should not be attempted in poor weather. It’s wise to take a couple of short days on approach to monitor the weather, acclimatize, and prepare your legs. The route requires crampons and ropes. Some sections require rappeling, and basic mountaineering is a plus. Few people cross Sherpani Col unguided.

It’s best to camp close to the pass. Expedition companies typically stay near the glacier's snout at 5,688m, leaving only 500m of altitude gain to Sherpani Col at 6,155m.

Sherpani Col

The ascent to Sherpani begins on a gentle snow slope but soon transitions to steep, loose rock. Once on the col, it’s a steep descent (with dangerous loose rock) requiring ropes to the flat glacier that links Sherpani and West Col (6,143m). It’s only a couple of kilometers between the cols, but in deep snow above 6,000m, it can be an energy-sapping slog.

Getting across in one day, especially for large guided groups, is rare but not impossible. Heather Hawkins, who trekked the GHT in 2016 as part of a tour, described the crossing as the hardest of her 152 days during the traverse.

“I had worried about this pass before the trip, but it was a fantastic, challenging day. It took 13 hours through deep snow and across hidden crevasse fields, but we crossed in one day. It was hard because of the altitude, and the weather deteriorated toward the end of the day, but by then, we were preparing to camp.”

Conditions are everything, and the earlier in the day you start, the firmer the snow is, and the more likely you are to cross both cols in a day.

World Expeditions, a tour company specializing in the GHT, builds in at least a day of flexibility for the crossing:

“If conditions are favorable, and the group is moving at a good pace, we may attempt both cols in a day. But in all likelihood, we’ll be camping at Baruntse Camp 1 on the West Col at 6,100m on the first night. [We then] descend the col to the Honku Valley the next day.”

The descent from West Col to the Hongku Glacier is not as steep as from Sherpani but still requires fixing ropes. From here, you’ll receive spectacular views of the Khumbu, provided the weather plays ball.

Rappelling down high passes

The next day is more relaxed, hiking across the moraines of the Hongku Basin, but it doesn’t last, the 5,000m+ passes come thick and fast till Rolwaling.

Amphu Labsta, 5,845m, is lower than the cols but a difficult glaciated pass with a narrow, exposed ridgeline. The descent requires fixed lines and rappelling. Hawkins regards this as the most technical section of the trek.

From Amphu Labsta, you descend to Chukung and then Dingboche. After some pretty remote trekking and camping, this is a return to civilization, with tea houses and (likely) many other hikers.

From Dingboche, you scramble up to cross 4,759m Cho La and then descend to the Ngozumba, the longest glacier in Nepal (the Khumbu is the largest). After crossing the glacier, you arrive in picturesque Gokyo. Here, you can take a day hike to Gokyo Ri for perhaps the best view of Everest without climbing a major peak. The trek up is brief but unrelenting, a one to three-hour slog depending on your fitness, ascending from 4,750m to 5,357m.

Whether or not you do Gokyo Ri, you’ll make a steep ascent leaving Gokyo. Renjo La (5,360m) is steep but not difficult in good weather. The descent is via huge stone steps. In good conditions, you can do the pass and descend to the village of Thame (famously, the childhood home of Tenzing Norgay and recently hit by catastrophic floods) in one long day. However, most groups either camp en route or stay in one of the tiny Sherpa villages along the way.

From Thame, there is one final big pass before Rolwaling and an extended period of lower-altitude hiking.

You can read Part II of the Great Himalayan Traverse, covering the route from Rolwaling to the Tibetan border and the differences between guided and unguided hikes, here.

On Jan. 1, 2025, adventurer, writer, and BBC presenter Alice Morrison will set off from the Jordanian border to cross the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia on foot. Expected to take five months over two winters, the north-to-south trek will pass through deserts, mountain ranges, and cultural sites before ending at the Saudi border with Yemen.

Saudi Arabia began issuing tourism visas in 2019, and Morrison jumped at the chance to explore it.

“I have been studying Arabic and the Middle East for 45 years, but Saudi has always

been closed to me. Now, I get to explore the heart of Arabia. I want to get past the politics and meet the people," Morrison said in a press release.

Women-centered adventuring

The politics of Saudi Arabia — and relatively limited opportunities for women in the country — will make for an adventure that explores the social as much as the physical terrain. Morrison will make a point of seeking out Saudi women to interact with. She'll be accompanied at various stages by Princess Abeer Al Saud, racing driver Mashael Obadain, guide Sara Omar, and a group of Saudi's first female wildlife rangers. Morrison is fluent in Arabic.

View this post on Instagram

Due to the extreme temperatures in Saudi Arabia during much of the year, Morrison will split her expedition over two separate winters.

Extensively traveled in the Middle East and North Africa, she has past experience trekking long-distance with camels. She's also cycled the length of Africa and walked across Jordan. Her book Walking with Nomads chronicles the effects of climate change on Saharian nomadic people.

"I am a mid-life woman (61), and I hope my adventure inspires others to get out and follow their dreams. I couldn’t have attempted this at 25; I needed the life experience to get me here," she said.

The Saudi Arabian trek will become a BBC series and a book when she's finished, but she'll certainly be making posts along the way. You can follow along here.

The body of a 27-year-old bushwalker who went missing last week has been found at Tasmania’s Federation Peak. Authorities have not yet released his name.

The man set out to hike the 72km Eastern Arthur Range Traverse last Tuesday. He had intended to finish over the weekend. When there was no word from him by then, a friend raised the alarm on Monday afternoon.

Five ground crews and a helicopter began a three-day search, and one of the ground teams found his body on Wednesday. They spotted a beanie hat, gloves, and backpack rain cover. This led them to the location of the body at the bottom of a cliff face on one of the approaches to Federation Peak. They believe the man perished in a fall.

Searchers have not yet managed to retrieve the body because of its difficult location and the high winds, which grounded the helicopter.

The bushwalker was experienced and had a military background but was not carrying a personal locator beacon or satellite phone.

The Eastern Arthur Range Traverse is not an easy route. It usually takes experienced hikers between six and nine days to finish.

“This walk is for physically capable and highly experienced walkers who are confident with navigation, cliffs, and rock scrambling, pack hauling, and extreme weather," said the Tasmanian Parks & Wildlife Service.

Lately, winds in the region have reached up to 100kph, and the rain-slicked trail has made for difficult, even dangerous walking. In the last 10 years, police have made 20 recoveries in the Federation Peak area, including six deaths.

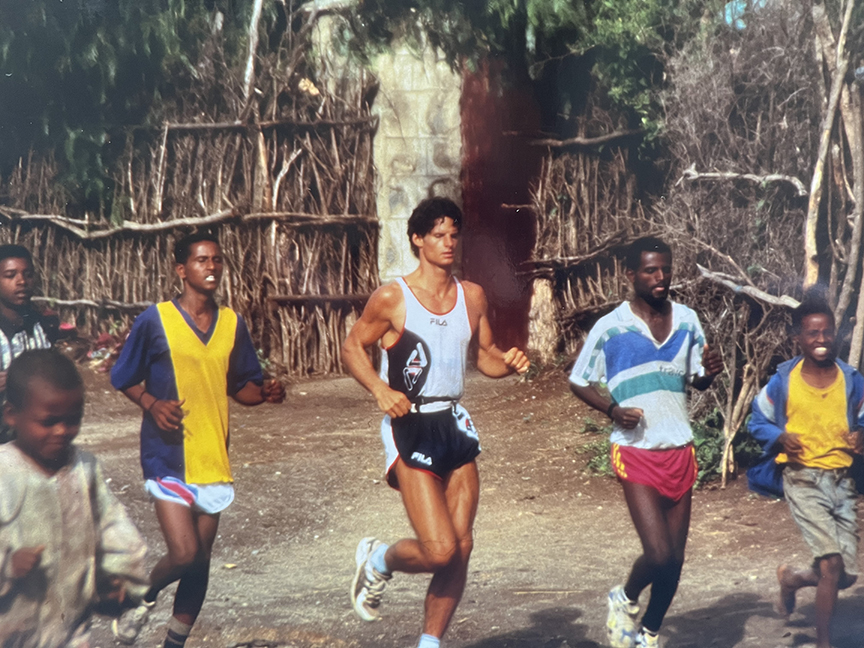

Nicholas Bourne, a British runner who ran the length of Africa 26 years ago, has dismissed the controversy over "Hardest Geezer" Russell Cook. Bourne would like to see Cook celebrated rather than embroiled in a debate over who was first.

Cook, 27, arrived in Tunisia on Sunday after running from the southernmost to the northernmost tip of Africa. On Instagram, the flamboyant runner with the scraggly red beard called himself “the first person to run the full length of Africa.”

The claim has caused controversy. As he drew near the finish, the World Runners Association (WRA) released a statement saying a Danish man named Jesper Olsen ran from Egypt to South Africa from 2008-2012.

The WRA ratifies around-the-world runs by examining logbooks, data, and GPS to make sure claimants are genuine. It also defines continental crossings. By its standards, ocean to ocean, with a minimum distance of 3,000km, counts as a continental crossing.

Definition dispute

The debate centers around what constitutes the length of Africa.

Some say the length of a continent is a straight line as the crow flies along its longitude or latitude. In Africa, that's 8,000km on a north-south axis.

But Cook’s team defines the “full length” as covering any route between the southern and northern extremes. A huge following defends this common-sense definition.

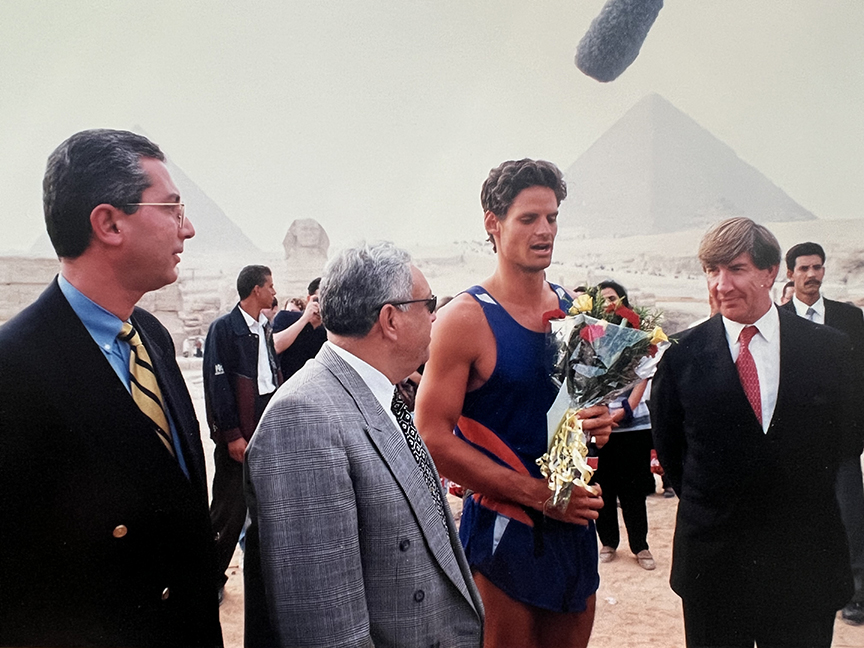

To add further confusion about who was first, it emerged that another man had run from South Africa to Egypt and was recognized by Guinness World Records. In 1998, Nicholas Bourne, then 28, ran for 10 months and finished by the pyramids in Cairo.

The WRA is preparing a new statement recognizing Bourne as the first. But Bourne himself thinks the controversy is overblown.

“The term 'storm in a teacup' springs to mind," Bourne told ExplorersWeb. "My feelings are congratulations to Russ because what he’s done is absolutely phenomenal. To run that distance and in that time, I have a very good understanding of how hard and difficult it is."

He believes there wouldn’t be this debate if Russ Cook had just claimed that he was the first to run from the southernmost tip to the northernmost tip of Africa, but that is beside the point.

“It’s so difficult with all the things that get thrown at you,” said Bourne, a former model who now runs a sports management agency. "Russell had some incidents of being held up by people with machetes and running through war zones. I totally understand what he's been through."

What's important

Bourne wants people to focus on what's important, such as the $1 million that Cook raised for charity.

The debate has stirred good memories for Bourne. He’s gone through old pictures and reminisced about all the people he met during the adventure.

Bourne went back and cycled the same route in 2015. What struck him most was how the cities had grown since his run in 1998, especially in Kenya.

What does the WRA say?

Marie Leautey is a member of the WRA and ran around the world in 2022. She also commends Cook’s achievement. But she says he is not the first in the WRA’s eyes.

She compares it to running across America. Many runners do different routes, some from San Francisco to New York, others from Los Angeles to Miami. They are all considered running across America.

“If I said I have run from Seattle to New York, it would be self-evident that I have run, in effect, a transcontinental length of the continent,” she said. "And people would not go into the details of where the crow flies, or the length of, the lines of latitude, etc.

“I would struggle to understand why this [would be any different in Africa]," she added. “Because the north-south axis of Africa has been run so few times (three as far as I now know), it would be easy and deceitful to [claim a] 'first in history' for every route a runner takes.”

Along with one distinctive Led Zeppelin song, the ravaging natural beauty of Iceland anchors the country in the popular lexicon. Lava flows, hot springs, glacial expanses, and meltwater lakes — they all proliferate in the land of fire and ice.

It’s become popular for tourists and trekkers alike. But at 500km from east to west, at an arctic latitude, don't expect a casual winter traverse.

Just ask James Aiken, a multi-discipline athlete who recently used every tool in his considerable kit to punch out the challenge safely and rapidly.

Aiken packed a sled with every practical contingency from ski wax to ice axes and planned for 35 days on the 530km hump. When he pulled into Þorlákshöfn, an improvised endpoint due to a hazardous river crossing he encountered midway, he was 14 days ahead of schedule.

View this post on Instagram

“When I finally stashed my pulk to finish the trip, it still weighed 45 kg,” he said. “But it’s like that on a pulk journey. You begin with all the supplies you might need because all you know is that you have to be self-sufficient. What you don’t know is what will happen along the way.”

That can be especially true during winter in Iceland’s exposed highlands. Sudden squalls commonly create whiteouts, and North Atlantic wind can rip across the continent at almost hurricane force.

The terrain itself can also cause havoc. Spindrift makes fragile cornices that overhang countless cliffs in choppy lava fields. Snow bridges often provide the only practical river crossings, and deep snow can make a skier feel like they’re stuck in mashed potatoes.

'Micro-navigation'

Aiken knew all this from one previous experience skiing across Iceland in winter, as part of a team in 2022. He also understood that planning and navigation would be critical. He’s an experienced skier, trekker, surfer, and especially sailor — which gave him a distinct orienteering edge.

View this post on Instagram

“I’ve sailed all my life, so I really love navigation. When I find myself in a semi-mountainous region in a whiteout, and it’s down to compass nav, I feel quite comfortable,” he said.

He explained that the ability to “micro-navigate” efficiently kept him safe and on schedule. Iceland’s compact, varied landscape can make for slow progress no matter what. And when snow cover makes some features obscure or invisible, the demand is much higher.

“A weird skill is looking at a map or chart and...to create a working reference of what the next hour is going to look like, so you’re not getting the map back out every three minutes. That way, you can keep your speed,” Aiken said, adding: “You’re dealing with all these little features in Iceland. So if you’re doing this in a white-out, you could quite easily ski off a five-meter drop.”

'Expensive taxi'

Of course, Aiken didn’t rule out that some emergency could occur. But he wanted to avoid calling in a rescue at all costs.

View this post on Instagram

“Have you ever heard of The Coldest Crossing?” he asked me. “Four young English guys tried to ski across Iceland in winter, and they got rescued three times in two weeks. Unacceptable.”

Averse to endangering others, Aiken sought a stronger solution.

A previous partnership with Arctic Trucks gave him the safety cushion he needed. The company re-engineers 4x4 vehicles to perform in winter. Aiken arranged an option to call in a paid rescue with experienced drivers if he needed it.

"I essentially gave myself a very expensive taxi," he joked. "But it was better than making people risk their lives."

Ambitious but resourceful

It's part of a pattern that proves Aiken's recognition of social value — another faculty he said was key to his success. He kept an open line of communication (mainly via Garmin InReach) to friends at the Iceland Meteorological Office. They helped him corroborate upcoming weather events and even advised him on eruptive conditions at Lake Askja, which lies in the caldera of an active volcano.

“You can’t do these things without local knowledge,” Aiken said.

Not everything went according to plan. Weather and snow conditions a few kilometers from both ends of the trip prevented a full ocean-to-ocean unsupported traverse.

Forty-five-knot winds once broadsided him in his tent. That’s plenty to destroy or carry away equipment, and could be a disaster in a remote area. All Aiken could do was reorient his snow wall and hang on.

Later, he abandoned his original endpoint when a dicey snow bridge made one river crossing too perilous.

View this post on Instagram

For Aiken, the trip constitutes one more step in the right direction. A sensible adventurer, he’s more concerned with longevity than statistics. The joys of the outing revolved around the simplistic charms of life on the trail.

View this post on Instagram

“I want to be ambitious but resourceful at the same time,” Aiken said. “If you just keep pushing yourself a little bit each time, you really move forward. Then in ten years, you’ve achieved quite a lot.”

One American skier is well on his way to finishing what’s arguably Sweden's most famous ski route.

Few set out to cover all 1,300 kilometers of the “White Ribbon" (or "Vita Band" in Swedish), an ambitious enchainment that traces Scandinavia's mountainous backbone.

Chicagoan Elijah Ourth is one contender.

The adventure photographer kicked off his journey in early January, and yesterday reported he’s reached Hemavan — the route’s snowy, spiky 700km halfway point.

Despite stiff challenges from storms and deep drifts, Ourth sounded plucky in an Instagram update. After churning through stubborn powder at 1 kph in Gäddede, he was excited for a pizza-tasting respite.

View this post on Instagram

Notably, Ourth is not tackling the trail in its traditional solo, unsupported style. But a team or group strategy has become more common in recent years.

This approach actually reflects the trail’s genesis in 1997, when Torkel and Annica Idestrom undertook their “Around Sweden expedition.” (Anecdotally, the White Ribbon’s first passage actually happened backwards — from northern Treriksröset, where all three Scandinavian countries meet, to Grövelsjön in the south.)

The route's website counts 97 total White Ribbon finishers since 2010. It hosts an unusually strong contingent this year. Ourth thinks it's a record winter for attempts.

One recent solo, unsupported skier to complete the trip was Sara Wanseth. The former Secretary General of the Scandinavian Outdoor Group knocked out the White Ribbon in 60 days in 2022. As Lundhags reported, she triumphantly posed on the bright yellow pylon of the famous Three Country-Cairn when finished.

Ourth now no doubt anticipates that same validation — but doesn't seem to be in a rush to experience it.

"I’m really looking forward to being even more in the high mountains and above treeline which is the environment I really like, and is super pretty! And it will be fun to get to share some parts with my friends who are along," Ourth told ExplorersWeb.

View this post on Instagram

Emma Schroder, 30, has completed her walk around the coastline of Britain. The entire 6,100km route took her two years and three months.

She initially started in 2020, but a few days later, the UK plunged into its COVID lockdown, so she headed home and waited. In July, 2021, she restarted.

Setting off from Lulworth Cove in Dorset, southwest England, she walked clockwise around country. Her method of staying on track was simple: She always kept the sea on her left.

She immediately regretted her chosen starting point: a steep uphill that led her to some precarious cliffs. But her sense of humor allowed her to make light of difficulties. Moments later, a man walked past her and took the downhill section like a mountain goat, while dressed in a suit and bowler hat. Later, she saw another man sprinting up the cliff and her first thought was, “What a psychopath.” Then she realized that she herself was on the first day of a two-year hike.

Inevitably, the hike included low points. A few weeks in, she drank some suspect stream water, which made her very ill. She had to stop and nap every hour as she slowly made her way across a beach in "the manner of a particularly lethargic snail.”

Six times she burst into tears while walking, but later realized that she was just hungry. Another time, she tried to take a shortcut and ended up adding 11 extra kilometers to her day. She ended up in tears three more times when she got lost, and then chastised herself for somehow messing up her "keep the sea on your left" rule.

A two-year walk also brought with it everything the British weather has to offer, from storms and seemingly endless rain to blistering summer heat. In 2022, there was so much rain that her constantly wet feet began to develop trenchfoot.

As a solo woman, she also had to consider her safety. At times, wild camping gave Schroder the willies, as her imagination ran wild. A sudden breeze sounded like someone touching her tent and any rustling outside became a potential axe-murderer. It pushed her out of her comfort zone and showed her courage and resilience that she didn’t know she had.

The aim of the walk was not to complete it as quickly as she possibly could. In fact, she admits she actually walked quite slowly.

“I have also now completed my Lands End to John O'Groats walk in record time -- maybe the longest anybody's ever taken to do such a walk,” she joked when she reached the northern tip of the UK.

She found a lot of joy in simple things -- coastal landscapes, people on the beach, kind offers from strangers. Usually, she camped, so she welcomed the occasional bed.

Schroder carried everything she needed with her, resupplying along the way. Her backpack generally weighed around 15kg. Most of the walk was solo, although friends and family joined her for sections. At other points, she met others who were trekking the coastal pathways and walked with them. One particularly kindred spirit was Juls Stodel, who recently completed her own walk around every bothy in the UK.

When she finally finished on Oct. 8, she admitted, “It's been the hardest but most rewarding thing I've ever done.” Yet she is already planning her next trip, and the possibilities seem endless.

Her jaunty website -- cheekily entitled mylegshurt.co.uk -- lists a few good-humored highlights from the trek:

The Nepal Tourism Board's vague announcement banning independent trekkers has brought confusion and anxiety to international outfitters and especially to would-be hikers getting ready to fly to Nepal.

There is uncertainty about whether the measure applies only to solo trekkers or also to independent (non-guided) tourists in groups of two or more. And to what extent will the Khumbu region possibly skirt this mandate?

Below, we try to provide some answers for those intending to visit Nepal after April 1.

The official document

First, here is the official document from Nepal Tourism Board (NTB):

What does it mean?

- As stated, note that the measure applies to ALL independent trekkers, not just solitary individuals. Any foreign trekker has to hire a guide in order to hike the "protected mountain areas" of Nepal. These areas would include several national parks such as Sagarmatha National Park, Langtang NP, Shey Phoksundo NP, and Makalu Barun NP, and Conservation Areas such as Annapurna's, Kangchenjunga's, Manaslu's, Api-Nampa's and Gauriskankar's. Here is a list of all protected areas of Nepal, including its lakes, hills, historical sites, and wildlife sanctuaries.

- The guide's services must be arranged through "authorized trekking agencies registered with the government of Nepal". That specification requires caution by those hoping to obtain the TIMS card first, then find a private guide, hoping to save some money. Official agencies will take care of everything, including the TIMS card, but at a higher price. Sources from NTB estimate that a guide changes $25 to $50 a day, but possibly much more for longer treks. That amount may be unaffordable for visitors on a shoestring budget. Group fees vary, depending on the trek. The popular Annapurna circuit costs from $850 to $1,100 for those joining a group guided by a local agency. If an individual trekker, a couple, or a small group hires a private guide, the fee is likely higher.

- Not surprisingly, the fee for the TIMS card has doubled. Now, it is 1,000 Nepal rupees for SAARC citizens (residents of South East Asia), and 2,000 rupees for the rest (except for diplomats, who are exempt from payment).

- Authorities justify the new restriction as a safety measure, but there is no mention of how this improves safety. In recent days, NTB members noted some incidents suffered by independent trekkers in the past that could lead to a "misperception" of Nepal as unsafe. However, it seems pretty obvious that the measure, agreed on with local operators and unions, is mainly to increase revenue.

- NTB promises to provide further details "shortly," but it is already rather late. Most trekkers planning to go to Nepal this spring have already bought their plane tickets. Some of them are on a tight budget. Those who are still uncommitted might discard Nepal in favor of other destinations where they can explore freely.

How about the Everest region?

Dawa Steven Sherpa of Asian Trekking told ExplorersWeb that the Khumbu Valley remains unaffected. Home to some of the most stunning mountain scenery in the Himalaya, including Everest and Ama Dablam, the municipality doesn't require TIMS cards. Instead, it levies a regional fee, to be paid on arrival in Lukla and combined with the entrance fee to Sagarmatha National Park.

Billi Bierling of The Himalayan Database is unsure whether this Everest exemption will continue in the future. "It was like that until last year, but I am not sure how the new regulations will apply," she said. "You never know in Nepal."

To learn more, ExplorersWeb asked some Sherpa mayors in the Khumbu.

"Individual tourists are heartily welcome and free to travel in the Khumbu region," Laxman Adhikari, ward chairperson of the Khumbu Municipality, told us. "All they have to pay is 2,000 rupees for a municipality-managed Trek Card, and 3,000 rupees to trek in Sagarmatha National Park."

The Khumbu Trek Card, a local version of the TIMS card, began last year. Issued by the Pasanglhamu Rural Municipality, it is mandatory for all foreign trekkers. Sagarmatha National Park requires another fee for entry.

These do not require visitors to be accompanied by a guide, in part because the Trek Card has a tracking system. The Khumbu region is one of the most popular in Nepal. Its many routes include the trail to Everest Base Camp and the Kala Pattar. The path to Gokyo Lakes, at the foot of Cho Oyu's south side, en route to the coveted Three Passes trek is also in this part of Nepal.

Reactions

The Trekking Agencies Association of Nepal (TAAN) has applauded the measure, but among stakeholders and trekkers, opinions are not so enthusiastic. Many point out that trekking is free in most other mountain areas of the world. Others believe that self-sufficiency is at the core of the trekking experience and do not wish to be guided around.

Some recall is not the first time Nepal has foisted peculiar new rules without warning shortly before the beginning of the spring season. A few years ago, it suddenly became forbidden to photograph members of other mountain expeditions.

"Don't push it," The Kathmandu Post headlines an op-ed piece. It advocates letting visitors decide whether they want a guide or not.

"Nepal has long been touted as one of the cheaper adventure destinations in Asia, yet it is getting costly, even by South Asian standards," the paper wrote. "Time may thus have come to rethink how the country projects its image as a tourist destination [but] we cannot chop and change our rules for incoming tourists without having a long-term vision for Nepali tourism."

As 2022 dawned, more than 100,000 Russian troops were stationed on three sides of Ukraine. Russian escalation in the long-running conflict with Ukraine seemed imminent, although many thought that Vladimir Putin was saber-rattling. Then on February 24, Russian troops descended on the country.

Against the buildup to this chaos, a young Ukrainian soldier, Alina Kosovska, had planned a long wilderness trek in the dead of winter. On January 8, Kosovska set off from the village of Velyky Berezny, in northern Ukraine. On her back was a hefty pack, stuffed to the brim with food and gear. Ahead lay over a month of solo hiking in midwinter on Ukraine's Transcarpathian Route. A 400km trail that takes the highest and most challenging sections of the Carpathian Mountains that lie within Ukraine.

A lesser-known trail

Unlike established trails such as the Appalachian Trail in the United States, the Transcarpathian Route is underdeveloped, with few outside visitors. Although not brimming with technical peaks, the route is wild, remote, and a significant challenge for a solo hiker in winter.

Undeterred, Kosovska, whipped herself into shape by running marathons. She also tested her key pieces of equipment in winter conditions, where reliability matters far more than during warmer seasons.

The Ukrainian soldier donned snowshoes and initially headed north, before looping south in the direction of the Romanian border. The burden of a heavy pack worsened when snow conditions became tricky. In the deep, soft forest snow, Kosovska found the going tough. She slowed down to less than 1 kph in places.

"There is a lot of snow there," she said. "It is not covered with an ice crust and it is difficult and long to walk on it, especially uphill."

Pushing through the slow days

At ExplorersWeb we cover a whole range of winter expeditions, from Antarctic sledding to winter treks in North America. When the pace slows and days of slogging through deep snow pile up, the only thing to do is to grind on. Quite often, we see adventurers fail, sometimes through a lack of experience in these conditions, and other times due to an unwillingness to ride out the monotony.

Kosovska's average pace was 1.5kph, and her longest day was 12 hours. Undeterred the Ukrainian soldier pushed on without faltering.

Every 20 to 60km, Kosovska had the opportunity to restock her mobile pantry at villages en route, although this depended on the area. On one section through the Chornohora range, which included climbing Hoverla, Ukraine’s highest peak (2,061m), the determined mountaineer had to push 100km without resupply.

“It is the most difficult because you have to walk almost 100km carrying all food, fuel, and supplies.”

Dropping off medical supplies

As well as collecting supplies, Kosovska made use of shepherd huts as a break from camping. There are typically three types of huts in the Ukrainian mountains: kolybas, where cheese dairies operate in summer, hunting cabins, and tourist shelters.

As in many parts of the world, there is a tradition to leave dry firewood, supplies, and medicine for future travelers. Kosovska took it upon herself to leave first aid kits in each of the huts she visited.

Few people are known to have attempted this route in winter, and these attempts are not well documented. Although navigational markings are reasonable in summer, the route Kosovska followed is less clear under a winter blanket. This also makes it more technically challenging.

However, Kosovska is the director of a charitable foundation and volunteer mountaineering group and guides tourists in the Carpathians when on military leave. This experience of the same mountains in summer no doubt helped her through the trickier sections.

A return to service

After 37 days of snowshoeing, covering some 400km, Kosovska arrived at the end of the trail in Dilove, near the Romanian border. It was February 14, just 10 days before the invasion. She had just completed the first known winter crossing of Ukraine’s Transcarpathian Route. She did it the hard way -- solo, in the coldest months, and against the backdrop of war.

Since finishing the trek, Kosovska resumed her military role as a drone operator in aerial reconnaissance.

Despite some leave to guide in the mountains in the past month, she will be heading back to the front lines in January. "I have been doing this since 2015 and will continue to do it as long as necessary," says the resolute young Ukrainian.

On Friday, March 11, 2022, winter explorer Emily Ford and Diggins — a retired sled dog and her adventure companion — pulled the plug on the final days of their 320km ski trek along the Minnesota-Ontario border.

They had fewer than 50km to go and were just two days out from the intended endpoint of Grand Portage, the area where several streams coalesce into Lake Superior.

Open water

The Duluth native explained that she had initially planned to reach Grand Portage by skiing the Pigeon River, which began near the trip's 270km mark. But when she and Diggins arrived at Pigeon River's banks, they found it "open and flowing" — it was thoroughly intractable.

Ford signed off on the trip without any palpable regrets:

This was a fantastic trip. I did what I set out to do: traverse the Boundary Waters by ski and paw. I am so incredibly proud of myself and Diggins! We saw one of the most spectacular places in one of the most spectacular seasons. No. We lived in it!

The Duluth native is a passionate advocate for, in her words, "getting kiddos into the outdoors". She uses her expeditions to fundraise for children's wilderness trips.

The adventures of Emily Ford & Diggins

Ford and Diggins's 28-day tour began on February 11 in Crane Lake, Minnesota. It was the duo's second epic winter trek in less than a year. The plan was to ski, skijor, and snowshoe from northwestern Minnesota across the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness (BWCAW) to Lake Superior, at the state's northeastern tip.

Their first expedition, and the one that put Ford's name on the adventure map, followed the 1,900km Ice Age Trail in Wisconsin. Because of its length and remoteness, the Ice Age Trail rarely sees a complete thru-hike even in summer. Ford is only the second person to walk the Ice Age Trail's entire length in winter.

Breaking Trail is a short film about Emily Ford and Diggins's 2021 expedition that premiered at the Banff Film Festival last November. The documentary is available to stream (for a small fee) through The Banff Centre and will show at select venues throughout 2022 as part of the Banff Festival's World Tour.

Most long-distance hikers are familiar with the thru-hiking Triple Crown of the United States’ Appalachian Trail (AT), Continental Divide Trail (CDT), and Pacific Crest Trail (PCT). But while thru-hiking continues to gain traction in the U.S. and Canada, the countries’ North American neighbor has lagged behind.

Both the Continental Divide and Pacific Crest trails have a terminus at the Mexican border. Mexico itself, however, has no thru-hiking scene to speak of.

One woman is looking to change that.

Mexican thru-hiker Zelzin Aketzalli completed the Triple Crown in 2019 on the CDT. In April of that year, she started it at a unique place, with a unique idea in mind — to see if she could extend it into Mexico.

Route research: Continuing the CDT in Mexico?

Aketzalli’s CDT thru-hike started 136km south of the U.S. border, in the Mexican state of Chihuahua.

“I started there because I wanted to see if it was possible to continue the route along the Continental Divide through Mexico and then connect to the Continental Divide Trail in the United States,” she told christiancentury.org. “I got a taste of what a Mexican portion of the CDT would be like.”

Quickly, though, she realized that northern Chihuahua was too dangerous for thru-hikers, so she shifted her focus to Baja California.

The long, narrow peninsula is already home to the world-famous Baja 1000 off-road race. Aketzalli saw hiking potential in it, though, based on an ancient missionary route.

The Camino Real: Aketzalli seeks to build a path along this ancient conduit

Catholic Jesuits oversaw the construction of the Camino Real from 1697-1768. The trail connects Loreto at the southern end of the peninsula with El Descanso in the north. Road construction and erosion have significantly blurred the original route, but much of it is still visible.

Aketzalli said research for a thru-hike based on the Camino Real is “almost finished”, but that significant obstacles still lie ahead. Routefinding challenges like avoiding roads while stringing water sources together stand in the way, as do bureaucratic roadblocks.

The project would be the first of its kind in Mexico, where Aketzalli says that thru-hiking is all but nonexistent.

“No one even knows what it is; it doesn’t really exist in Mexico as a sport or as a concept. That’s why education and promotion are my first challenges and objectives in Mexico,” she said. “I think the biggest obstacle will be introducing the people of Mexico to this type of sport. Another is getting support from the government for these kinds of trails.”

She also hopes the possible 1,100km route will focus attention toward the environment and empower Indigenous communities by economic proxy. For her, thru-hiking is a spiritual undertaking. She hopes that her work can help other Mexicans feel the same way.

“I have had many spiritual experiences on my hikes. For the Nahua people of Mexico, Mother Earth is called Tonantzin. She takes care of you because you take care of her,” Aketzalli explained. “Walking the Camino Real offers us a chance to explore and better understand our relationship to our land and history.”

You can follow Zelzin Aketzalli on Instagram.

As borders reopen, long-distance cycling has become more popular than ever. It's low cost, eco-friendly, and allows you to go almost anywhere -- even Antarctica.

ExplorersWeb has rounded up six exciting long-distance bike tours happening right now. Some of the cyclists are athletes. Others are relatively new to life on two wheels. Their expeditions range from round-the-world marathons to extreme Arctic adventures.

Arctic World Tour

Italian cyclist Omar Di Felice started his journey on February 2. He is cycling 4,000km through eight arctic regions. Di Felice began with the first winter bike crossing of Kamchatka, the wild peninsula in the Russian Far East. He covered that 740km in five days.

Next, he is cycling 1,200km from Murmansk, Russia through Finland and Sweden to Tromsø in northern Norway. That section is already underway. On February 14, he crossed into Finland.

From Tromsø, he will cycle short sections in Iceland and Greenland before shifting to Western Canada. From there, he will cycle to Alaska.

Siberia 105°

Stefano Gregoretti and Dino Lanzaretti began a 2,000km expedition through Siberia on January 13. First up, an ambitious 1,200km ride from Oymyakon to Verkhoyansk. These two villages are the two coldest settlements in the world.

But after just 620km, they aborted on February 4. The duo had struggled from the start. In the first few days, they had problems with the gearboxes on the bikes. Then strong winds forced them to push their bikes, even downhill. It's unclear whether that was because of the strength of the wind or the ungodly wind chill.

Their only options were to abort or to wait out the weather, but their one-month Russian visas would expire before they could complete a postponed expedition. They chose to abort.

Chains and Chords

Louisa Hamelbeck of Germany and her American boyfriend Tobi Nickel are making their way “around the world with bikes and a guitar”.

They left Salzberg, Austria last June and plan to cycle for the next two to three years. Since setting off, they have pedaled through Austria, Slovenia, Croatia, Montenegro, Albania, Greece, and Turkey. From Turkey, they flew to Florida and have now reached New Mexico.

It took them 82 days to travel the 3,250km to their first big milestone: Artemida, near Athens, where Tobi’s father lives. Here, they spent six weeks seeing friends, researching the next few sections of their route, and servicing their bikes.

They wanted to go to the U.S. by boat but they are traveling on the cheap. They found it impossible to find an affordable ship that would take their bikes. In the end, they cycled to Turkey and flew to Miami on December 9.

Explore for Huntington

Dimitri Poffé is biking 15,000km across Central and South America. As the title of his project suggests, he is doing this to raise awareness of Huntington’s disease, for which he tested positive three years ago. Unfortunately, the disease runs in Poffé's family: His sister has had it for eight years, and he lost his father to it 15 years ago.

Currently, he is asymptomatic but he knows that he will develop symptoms between 35 and 40. The diagnosis “was a trigger to realize a dream: to go around the world.” He has chosen Central and South America because the disease most affects that region of the world.

Poffé set off on October 3 from Mexico City. He plans to pass through Guatemala, El Salvador, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, and Panama before cycling through South America.

He reached Guatemala on January 20 and has spent a month exploring the country on two wheels. His next stop is El Salvador.

Migratory Bikes

Camille Pages and Antoine Jouvenel are cycling from the south of France to Nepal. Carrying 40kg each, the French duo will cross 19 countries and cover 20,000km.

Both were relatively new to cycling when they started planning their expedition. They quickly realized that they had a lot to learn.

After a COVID delay, they began their “cyclo-nomadic adventure” in July 2021. Nine days later, they reached Italy. Here the inexperienced pair faced some of their most challenging routes, including Izoard Pass (made famous by the Tour de France) and the Dolomites.

So far they have cycled through France, Italy, Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro, and Albania.

Voies Recyclables

Brewenn Helary and Lea Schiettecatte want to complete a zero waste, zero carbon, trip around Europe. Voies recyclables translates to ‘recyclable paths’.

Their circumnavigation of Europe will cover 15,000km. They set off on February 12 from their hometown of Iffendic, in France. Their round-Europe trip will take them through 20 countries.

Since the pandemic, four long-distance hiking trails have opened around the world. They all differ in distance and difficulty but are ideal for working off your shutdown restlessness.

The Red Sea Mountain Trail: Egypt

The Red Sea Mountain Trail (RSMT) opened in 2019. At 170km, it is mainland Egypt's first long-distance hiking trail. For the gateway beach resort town of Hurghada, the trail is also a community tourism initiative that aims to preserve the endangered Bedouin culture.

The RSMT is a network of ancient routes that the Bedouin have used for centuries. The Khushmaan clan of the Maaza, Egypt’s largest Bedouin tribe, manages it.

“We want the Red Sea Mountain Trail to diversify Hurghada’s tourism and create a space for slow, immersive travel in which the Bedouin can communicate their rich knowledge of their homeland to outsiders,” Ben Hoffler, one of the founders of the trail, told Afar magazine.

Completing the full 170km would take most hikers 10 days. The trail is so new that currently, no hiker has completed the full distance. Though many would see 15-20km a day as a manageable distance, the walk is not easy. There is not a well-trodden path to follow, there is considerable elevation gain, and some sections require exposed scrambling.

Everyone who wishes to tackle the trail must do so with Bedouin guides. For centuries, these nomadic desert tribes have been the only people to walk through these mountains. The guides aim to show visitors the “wisdom and beauty of Bedouin heritage”.

This month sees the first-ever group trying to complete the full thru-hike. So far people have only completed smaller sections. For those who don’t have 10 days to spare, or who want a less demanding trail, you can choose shorter, flatter guidedcircuits.

The founders of the trail have also created supplementary ‘hiking hubs’. Each hub consists of a web of secondary routes that fork off of the main trail, and centers around a specific mountain massif.

The six hubs can add a further 600km to the journey. The Red Sea Mountain Trail Association is already exploring the idea of expanding the main path into a 1,000km route that follows the Red Sea and provides economic support for other clans and tribes.

The Michinoku Coastal Trail: Japan

In March 2011, a 9.0 magnitude earthquake and tsunami ravaged the northeast coast of Japan. It is the fourth largest earthquake since records began in 1900 and it claimed over 18,000 lives.

In the decade since, Japan has been rebuilding its communities, but one initiative in the Tohoku region has gone relatively unnoticed. Among all the reconstruction, they have also built a new hiking trail.

The Michinoku Coastal Trail (MCT) stretches for 1,000km along Tohoku’s eastern coastline. Michinoku is the ancient name of the Tohoku area. Officials hope that the trail will increase tourism in the little-known area and help with the region's long-term recovery.

The MCT officially opened in June 2019 but it remains relatively untouched because of COVID travel restrictions. The route connects Hachinohe in Aomori Prefecture with Soma in the Fukushima Prefecture.

This off-the-beaten-track route “follows the Pacific Ocean coast over grassy promenades, through forests, along remote beaches and soaring clifftops and to fishing ports, some tiny with a few one-man boats and others with fleets of ocean-going trawlers," Paul Christie from Walk Japan told the BBC.

Completing the full trail takes anywhere from 6 to 12 weeks. Those daunted by the prospect of a three-month trek can do smaller sections. The route runs through four prefectures of Japan: Amori, Iwate, Miyagi, and Fukushima.

The Michinoku Coastal Trail website breaks these down even further into 28 smaller hikes. It explains which ones are best for newbies, and which are more challenging.

Grampians Peak Trail: Australia

The Grampians Peak Trail runs 160km through Grampians National Park in Victoria, Australia, from Mount Zero in the north to Dunkfield in the south. The Victoria government bills it as a “challenging" 13-day hike.

The trail traverses several mountains and bypasses waterfalls, sandstone rock formations, grasslands, ravines, and eucalyptus forests. Some of the highlights include the Grand Canyon, the Major Mitchell Plateau, and the summits of Mt. Difficult, Mt. Abrupt, and Mt. Sturgeon.

Even though you summit several mountains, the trail was not built as a sporting route or place to see who can complete it the fastest.

Known as Gariwerd to the Djab Wurrung and Jardwadjali, who have lived here for over 22,000 years, the Grampians feature aboriginal rock art, as well as abundant wildlife -- 40 different mammals, 28 reptiles, and countless birds. There are also over 1,000 plant species, including 130 types of orchids.

Navigation is tricky. The route crosses large rocky expanses without a worn trail to show the way, only sporadic yellow markers.

After a decade of work and a cost of $33.2 million, the GPT finally opened in November 2021. Eleven new campsites, deep within the park, offer simple amenities. Water is available either at these campsites or at designated nodes, identified on the trail website.

The Walk of Peace: Slovenia and Italy

The Walk of Peace trail stretches 270km from the Alps to the Adriatic Sea, along the World War I front line between Slovenia and Italy.

The Walk of Peace opened in April 2020 and follows the Isonzo Front, which saw 12 battles between Italy and the Austro-Hungarian Empire from 1915 to 1917. Over 350,000 soldiers died here. The trail aims to restore the historical sites in the region.

In part, the trail is a history lesson for active students. Mountains and rivers compete with museums and memorials that give trekkers insight into what the region endured during World War I.

The Walk of Peace begins in Triglav National Park. From here, hikers follow the Soča River through Solvenia’s wine country. Leaving Brda, the trail meanders through the Karst region before descending toward the Adriatic. The endpoint is Trieste, Italy.

The main trail splits into 15 one-day sections and is accessible for hikers of varying abilities. Two further trails and a myriad of smaller paths branch off from the main route. One subtrail leads to Kranjska Gora, a winter sports hotspot. The second ends at the town of Bohinjska Bistrica. Smaller paths loop to historical sites.

Throughout the walk, peace and natural beauty contrast with the setting for wars fomented by kings, politicians, and their generals.

The Island Walk: Canada

Prince Edward Island is Canada's smallest province, but that doesn't mean it's short on attractions. Cradled in the Gulf of St. Lawrence by New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, it's famous for its red soil, beaches, and seafood.

It's also the fictional home of Anne of Green Gables and produces outstanding potato crops.

Now, it features the country's newest hiking trail. The 700km Island Walk spans the picturesque island's entire perimeter in 32 sections. Hikers can finish it in a month of longish day hikes.

Along the way, inland and coastal passages reveal beaches, farmland, intermingled hardwood and softwood forests, and cozy towns. The scenic highlights look like they're ripped right out of a coffee table book.

Partnering inns and hotels along the way help travelers with various logistics like luggage transfer services and kitchen access.

Hiking the trail requires notably minimal equipment -- basically, a day pack and a comfortable pair of shoes. Bicycle rental services are also available.

The Island Walk season generally starts in May and ends in October. July and August are heavy tourist months on Prince Edward Island, so note that accommodations might be in peak demand at that time.

The trail officially opened in November 2021. For more information, including FAQs and a section-by-section breakdown, go to theislandwalk.ca.

On February 2, ultra-distance Italian cyclist Omar Di Felice hopped on his bike to start a long, cold ride.

In total, Di Felice's westbound route will cover 4,000km of arctic terrain, from Kamchatka to Alaska. His Arctic World Tour will include stages in Scandinavia, Iceland, and Greenland. He hopes to inspire people to travel by bicycle and point out the impact of fossil fuel emissions on arctic landscapes.

Di Felice's route and trip details

Di Felice hopes to complete the cycling in three weeks. Currently, GPS tracking shows that he's already covered a good chunk of the 800km he planned to ride between the capital of Petropavlovsk-Kamchatskiy and Ust'-Kamchatsk.

He will then proceed to Murmansk, Russia, near the Norwegian border. Stages between Tromsø, Norway, through Finland and Sweden, will take him another 1,500km. Di Felice will then go island-hopping; short stages in Svalbard, Iceland, and Greenland follow.

Finally, he will travel (by some means other than cycling) to Whitehorse, Canada, for a long final stage ending at the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta in Alaska.

Di Felice has a specially-outfitted touring bike to crunch through the snow. Along with his 4,000km on the bike, he's imposing a rule to supply and support himself locally when possible. Even if it's well below zero, he plans to pitch camp if he can't find indoor accommodation.

You can follow Di Felice via social media channels. He plans frequent updates, with episodes featuring locals and arctic scientists. The ultra-cyclist wants to highlight his interview subjects' experience living in areas under changing climatic circumstances.

Di Felice has previous experience with cold-weather cycling. He already circumnavigated Iceland this winter via the 1,294km Ring Road. The trip took him 19 days.

One year ago, 10 elite Nepali climbers raced for and made the first winter ascent of K2. This year, the game will be less epic, but even more dangerous than K2: climb Cho Oyu in winter from the Nepal side. And now a second team has joined the fray.

Led by Pioneer Expedition's Mingma Dorchi Sherpa, the new team is heading to Cho Oyu's south side with the same goal as the expedition led by Gelje Sherpa: to open a new route for commercial climbs.

Competitors

Mingma Dorchi confirmed to Stefan Nestler that both teams will climb separately, although he was willing to collaborate with Gelje's team on the last stage of the climb.

There can be only one commercial route