This week, a team of maritime archaeologists completed a detailed underwater study of the wreck of the SS Terra Nova. Their findings paint a vivid portrait of the famous ship's final hours, and of its fate in the 80 years since.

Launched in 1884, the Terra Nova lived a peaceful life as a whaler until she joined Robert Falcon Scott's ill-fated Antarctic expedition in 1910. Unlike Scott and the other members of the South Pole party, she survived the expedition but fell victim to pack ice during World War II and sank off the coast of Greenland.

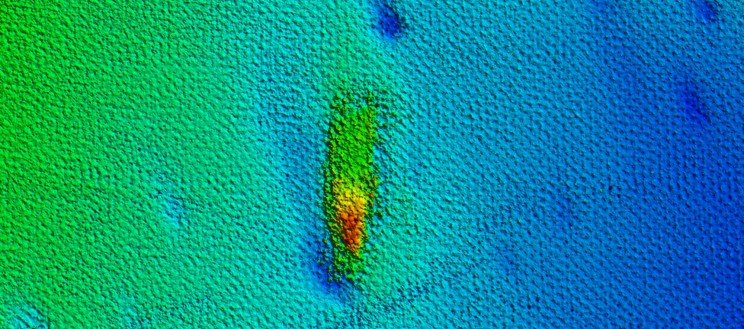

There she rested until 2012, when marine survey technician Leighton Rolley proposed the general location of her sinking as a test project for new sonar equipment. The sonar scans detected various wreck-like features on the sea floor. One of them exactly matched the recorded length of the SS Terra Nova, 57m. After 70 long years, they had found the ship.

The survey team then lowered what was officially called the Simple High Resolution Imaging Package (SHRIMP), which was, in practice, simply an underwater camera and four flashlights attached to a cable. SHRIMP revealed the wooden skeleton of a wreck.

Terra Nova in detail

Now Leighton Rolley is back at the site of the wreck, this time with the equipment necessary for a full visual survey. The expedition vessel, MY Legend, is a high-tech yacht accustomed to polar cruises. Expert divers and a submarine have replaced SHRIMP, exposing details of the wreck.

Their survey confirmed the SS Terra Nova's identity. They also found that the bow had violently split in half. Remnants of gear still on the deck testified to the rapid evacuation of the ship in 1943.

"One of the most powerful moments was discovering the helm station near the stern — a symbolic and moving find," wrote submarine officer Aldo Kuhn. Photographs from the survey also show the ship's wheel, still intact after 80 years in the frigid water.

Still supporting life

But the team didn't only find the remnants of life. They found life is still there.

According to Kuhn, "a beautiful marine ecosystem is now thriving on the wreck, bringing new life to this historic site." Rolley wrote that the team saw corals, anemones, and fish living on the old oak whaler.

Shipwrecks often act as havens for marine life. Plants and corals grow well on wood in underwater environments, and small fish use the structures as shelter. Many oceanic organizations worldwide take special care to preserve the ecological role of shipwrecks.

Sir Ernest Shackleton is one of the most heavily decorated UK explorers of all time — but most of his hardware has vacated the island.

In fact, reports indicate only one of the intrepid polar adventurer’s medals remains in the country. And, at least for now, the British government plans to keep it that way.

Shackleton’s Polar Medal includes clasps for each of his three major Antarctic expeditions from 1902-1917. The exploits included the famed survival story of the Endurance crew, which lost its ship to sea ice but amazingly, saved themselves with no casualties. In recent years, the epic escape has turned Shackleton into a model of corporate leadership.

Varying reports value the medal at around £1.7 million.

Officials fear that despite its vast symbolic value, it could land on the auction block and wind up in the hands of an international collector. British export authorities stepped in to prevent that outcome, “deferring” a decision on an export license for the medal until May 1, the BBC reported.

Representatives with the Shackleton Museum, located in the explorer’s hometown of Kildare, Ireland, have advocated for Irish state entities to invest in the memento and protect it in its “natural home” in the museum.

Previous auction demand for Shackleton’s medals has proven high. A clutch of awards fetched $580,000 at a Christie’s London event in 2015 — a figure that soared above expectations, auction officials said at the time.

You can't imagine Amundsen or Shackleton complaining about chafed thighs during a polar trek. But in recent years, Instagram is awash with gory photos showing what Antarctic travelers have had to endure. Victims are often, though not always, women.

In truth, this isn't just chafing. Had the great polar explorers of old had such a terrible affliction, they would have mentioned it somewhere, tough though they were.

What is it? And why the Antarctic, in particular? Lots of people ski across Greenland and elsewhere in the Far North and don't seem troubled by it.

I've done many sledding expeditions in the Arctic and neither I nor my partners have ever had it. Or maybe I've had a mild case without realizing it. For most of those expeditions, I've used synthetic base layers. After merino became popular, I tried it on colder trips, since merino is a little warmer than the same thickness of synthetics. After two or three weeks, a rash began to form on my legs. At this point, I changed to my backup synthetic underwear, and the rash went away. This happened on two expeditions.

I think the first time I saw real polar thigh was when two Australians, James Castrission and Justin Jones (Cas and Jonesy), did a three-month Antarctic trek in 2011-2. They documented it in their entertaining film, Crossing the Ice. One of them developed a gory, raw thigh and showed it in the film.

Merino for three months

They had a merino sponsor, and considering my own small experience with a merino rash, I assumed that this was due to wearing wool underwear for three months. Likely they didn't have synthetic backups or -- as novice polar travelers -- didn't draw the connection between the ailment and their underclothing. Merino is very comfortable, but few people have worn a single piece of long underwear for two or three months, never taking it off, for us to know whether the salt or some bacterial buildup in that natural fiber causes a skin irritation that can worsen into polar thigh.

To better understand, I asked a who's who of polar travelers and guides, including Borge Ousland, Richard Weber, Eric Larsen, Eric Philips, Erik Boomer, and Lars Ebbesen. They didn't all agree, but two theories emerged: that it had something to do with wool and that it was a kind of infected frostbite.

Weber wears only synthetics

Richard Weber is one of the proponents of the wool theory and has long insisted that his clients only wear synthetics. "I believe it is caused by wool underwear that does not breathe properly, in combination with waterproof/breathable wind pants in cold weather," he says. "I suspect it is some bacteria going crazy."

He adds: "I have never had it because I always wore thin synthetic underwear and breathable wind pants. But some Russians got it a bit on Polar Bridge [the 1988 Russian-Canadian expedition across the Arctic Ocean], as they wore very thick wool underwear."

Weber says that on his last South Pole trip, one of his female clients wore wool, against his strict instructions. "She started to get [polar thigh], switched to synthetics, and it went away," he said, echoing my experience.

Larsen: Antarctica both warmer and windier

Eric Larsen agrees with Weber. "I guided my first South Pole trip in 2008 and we were talking about it then," he said. "It’s definitely more of an Antarctic than an Arctic phenomenon. I believe it’s because it’s both warmer and windier in Antarctica."

Larsen believes that wool might be a factor not because of rubbing or chafing but because wool doesn't wick moisture away from the skin as synthetics do. Like Weber, Larsen always wears synthetic base layers and has never had the condition.

"In my opinion," adds Larsen, "the mechanism of polar thigh is that your thighs get too cold, but without a lot of nerves, you don’t feel it much. [Then you] get some sort of cold damage. This is exacerbated if the skin is wet from bad moisture management. As that skin becomes damaged, it itches, you scratch it, it gets infected, it’s not clean, it gets cold damaged again, you sweat too much…"

"This happens in Antarctica more because it’s so much windier and you’re basically skiing into a headwind all the time. It’s also warm, and people don’t do a good enough job with ventilation."

Extra weight

Eric Philips thinks that merino may contribute to polar thigh but admits that he isn't sure. "I have had clients with polar thigh, and my daughter gets it," says Philips. "It seems to be more prevalent in women and people with a higher proportion of fat.”

Philips recalls that Jon Muir, one of his partners on a 1998 South Pole expedition, had a mild case of it. "Jon was definitely wearing wool," he said.

Note that some travelers doing extremely long polar treks, including the Australians Cas and Jonesy, pack on a dozen kilos or more before their expedition, to minimize the amount of food they need to carry in their sleds. So even people who are usually thin sometimes start their expeditions with significantly higher amounts of fat than they are used to.

Borge Ousland had polar thigh himself on an early expedition, his 1995 South Pole trek.

"It was probably caused by chafing that got infected," Ousland told ExplorersWeb. "But I think in most cases, it starts off with a frostbite that turns into a wound and eventually gets infected. When I started using longer and more insulated underwear, and was careful to avoid chafing seams, I have not had it.

"My theory is that the thighs are well insulated with fat and few blood vessels to keep the skin warm, and it's easy to get small local frostbites there."

Better parka design

Women have more fat on their legs, so may be more vulnerable, he suggests. Ousland's custom-designed Norrona shell is much longer than most models, further protecting the thighs from wind and cold. Roland Krueger, the first German to go solo to the South Pole, likewise lengthened his jacket by sewing extra fabric onto it.

Lars Ebbesen, the manager for Ousland's polar outfitting company, is very familiar with polar thigh.

"It is frostbite, pure and simple," Ebbesen insists. "It shows up on the legs in places where circulation/protection is scarce. Like the inside."

He admits that it looks like an ordinary red rash at first, but it is almost always the beginning of frostbite.

"And this is very often where it goes wrong," he warns. "If you do not take immediate precautions, and just think cleaning/treating the rash is the way to go, you lose very valuable time in stopping the frost injury. It gets a foothold, and there is no way back."

He says that at the first sign of a rash, the traveler must immediately protect the area, adding insulation or even wearing down pants. If you let it advance too far, it can become an open wound.

Advanced polar thigh won't heal in the cold

"If it gets that far, it is extremely difficult to heal in the cold," says Ebbesen. "It usually keeps growing. Even though places like Antarctica are the most pristine and cleanest in the world, you risk getting infected. So bringing antibiotics can be life-saving."

Given the potential for delays in rescue, the condition -- if advanced enough that the infection gets into the bloodstream -- can be fatal, he says. It is even dangerous after an expedition ends and the traveler is reintroduced to a warm environment. Circulation improves, and the infection can spread quickly.

To prevent polar thigh, "we at Ousland Explorers will not let anybody on the ice without PrimaLoft shorts or pants," says Ebbesen. He points out that many polar travelers, men and women, wear down skirts these days to protect their thighs. Norwegians, he says, often wear an extra layer of Brynje, or mesh underwear, beneath their longjohns to trap air and increase warmth, yet allow moisture to wick away.

Eric Larsen agrees with that precaution: "I also wear long underwear ‘cut-offs’ -- an extra pair of light long underwear cut off at the knees," he says.

Harder for those who sweat a lot

Another important consideration: We all respond differently to cold. At -35˚C, my wife's face actually hurts, while mine is perfectly comfortable. (A main reason why we've done many kayaking and backpacking expeditions together but never a sledding trek.) I perspire hardly at all while pulling a sled, while some partners are drenched in sweat. People who sweat heavily are always on the razor's edge between freezing and sweltering. Others have a wide margin of equilibrium between the two extremes.

"Sweaters" need to be much more diligent with self-care. Bottom layers take much longer to swap out or layer than top layers, because you have to remove and replace boots and skis. I almost never change bottom layers during the day -- it doesn't matter if I'm a little warm down there, because I don't sweat much -- whereas I sometimes tweak top layers, headwear, and gloves several times an hour.

Erik Boomer admits that he's a heavy sweater.

"I really need to vent and swap layers a lot," says Boomer. "I get cold knees, thighs, and parts of my chest and need to keep an eye on those areas, especially on cold windy days."

When he first did winter treks on Baffin Island, he didn't wear enough layers on his legs.

A close call

"I got by well, but one very cold evening, I felt the beginnings of polar thigh," he recalled. "It just felt warm and like windburn. I’m sure if I kept exposing my thighs to that, it would have developed. Now I put on puffy pants more often and wear more layers in general."

He believes that people are moving faster these days and wearing fewer layers, and that is something to be aware of. "Even if hands and feet and nose are good, you can still get cold thighs."

Whether due to wool, sweating, infected frostbite, or some medical condition such as cold panniculitis, polar thigh seems at least easy to circumvent:

- Although not everyone believes that wool is a contributing cause, synthetics work, so if you want to be safe, wear synthetic underwear. Or at least, have it as a backup, so you can change into it at the first sign of a rash.

- To counter the unique combination of summer warmth and icy wind in Antarctica, wear a down or synthetic skirt or an extra pair of knee-length mesh underwear.

- At the first sign of a rash, do something -- better moisture management, warmer leg layers, a change of clothing -- before it worsens to the point where it becomes infected. In the polar regions, some things you just tough out, but this is not one of them.

As a dedicated technophobe, I’ve always felt a certain kinship with the English explorer H.W. Tilman (1898-1977), who would have thrown a GPS into the trash, assuming he ever had one. On his mountaineering expeditions, he engaged in alpine-style climbing and refused to bring any oxygen equipment with him, while in his seafaring trips, his boats carried no technical devices other than a compass, a sextant, and a short-wave radio. Nor did those boats have engines, since he preferred to be under sail. “Radar is a superstition,” he once wrote.

In 1986, I was in the village of Angmagssalik (now Tasiilaq), East Greenland, and I happened to ask a local Danish shipbuilder if he’d ever met Tilman, who’d visited these parts several times in his pilot cutter Mischief.

“Funny you should ask me that,” the fellow said. “I repaired the Mischief in 1973 when it was struck by ice floes. While I was doing my repairs, Tilman climbed that mountain over there every day” — here he pointed to a steep icy mountain — “to examine the ice conditions in the fiord. Or that’s what he told me. I actually think he climbed the mountain just for the hell of it. Because he was that sort of guy. By the way, he must have been 75 years old at the time.”

Just walk out the door

Tilman was indeed “that sort of guy.” A would-be explorer once asked him how he could get on an expedition, and “Bill” (as his acquaintances called him) replied, “Put on a good pair of boots and walk out the door.” He himself lit out for the territory whenever possible. For him, that territory included the battlefields of war (he served valiantly in World War I), the wilds of Africa (he bicycled east to west cross the continent — a first), the Himalaya (he made the first ascent of Nanda Devi in 1936), Patagonia (he sailed through the notoriously difficult Strait of Magellan), or some remote part of the Arctic.

So how did he travel? By foot, by boat, or by bicycle. “Only a man in the devil of a hurry would fly to his mountain, foregoing the lingering pleasure and mounting excitement of a slow, arduous approach,” he once wrote. He seemed never to be in the devil of a hurry himself, which makes him quite different from a number of better-known explorers.

Tabasco sauce essential

Like many an English explorer, Tilman was something of an eccentric. Or maybe he was just a man who marched to the beat of his own drummer. You can experience his idiosyncratic march by reading any of his 15 travel books, particularly the Mischief ones.

In doing so, you’ll learn that he thought Tabasco sauce was an essential item to be brought on an expedition, since anything, even lifeboat biscuits (i.e., hardtack), could be made edible with a few drops of it. You’ll also learn that he advertised his Mischief expeditions with these words: “Hand wanted for long voyage in small boat. No pay, no prospects, not much pleasure.” Believe it or not, he got plenty of enthusiastic replies.

Since I’m an arctic hand myself, I have a particular interest in Tilman’s arctic expeditions, all of which took place in his later years and featured the Mischief as well as another pilot cutter called the Sea Breeze. Among the reasons he liked the Arctic was that he didn’t have to submit to any authority other than himself.

“No bother, no police, no customs, no immigration or health officials to harry us,” he wrote about it.

He could have added something like “only a wondrous natural world” to end this description. At 3,000 feet on a mountain in Greenland, he found a yellow poppy and was utterly enchanted!

A hard trek at age 65

Bylot Island is rugged island off the northwest coast of Baffin Island in the Canadian Arctic. Taking a boat from the Inuit village of Pond Inlet, I once tried to hike across it, but I didn’t get very far before my energy gave out. Not so Tilman! At age 65, he was considerably older than I was, but he made a first crossing of the island in 15 days. That crossing included negotiating his way over an ice col that was 5,000 feet above sea level. “The hardest 50 miles I have ever done,” he said with a grin.

Even more remote than Bylot is Jan Mayen, a Norway-owned island to the east of Greenland. Rising up from it is Beerenberg, a 7,470 foot mountain that’s the northernmost active volcano in the world. I climbed it in three days and ended up being blanketed by volcano ash. One of my companions who didn’t make the climb claimed not to recognize me when I returned to our base camp.

Tilman himself was eager to climb Beerenberg, but before he could do so, the Mischief got stuck on an offshore rock. A goodly percentage of the boat’s supplies were lost, but the item he most lamented the loss of was his pipe. The Norwegians who manned the island’s weather station tried to save the Mischief, but to no avail. Tilman felt like he’d witnessed the death of a dear friend. Even so, he found another friend in the Sea Breeze, and the following year he stopped at Jan Mayen en route to Scoresbysund in East Greenland. “Mr. Tilman, I presume?” one of the Norwegians said to him.

Hunger for adventure grew stronger

As he aged, his desire for adventure seemed to grow stronger. He wanted to spend his 80th birthday in the Arctic, but since that birthday was in February, Antarctica seemed like a more appropriate destination. Thus he sailed south in a gaff-rigged cutter called En Avant with a young explorer named Simon Richardson. In Rio de Janeiro, he sent letters to several of his friends in England. Then — silence. The En Avant vanished without a trace somewhere in the South Atlantic. Tilman was doubtless pleased to have breathed his last in this fashion rather than in a hospital or an old folks home.

My thanks to librarian Mary Sears for providing me with some obscure facts about Tilman’s life.

When Antarctica's Discovery Hut was built for Robert Falcon Scott's first expedition in 1901, no one expected that it would survive until the next century.

The little building became a refuge for many more explorers during the Heroic Age of Polar Exploration, including Ernest Shackleton.

The YouTube channel Out There Learning takes a tour of the hut with Lizzie Meek of the Antarctic Heritage Trust. Meek helps conserve the building, along with other huts in the McMurdo area. These structures offer a glimpse into the hardship and heroism of polar explorers in Antarctica.

Meek also details the many improvements that have recently been made to the hut. Likely, it will continue to survive the continent's brutal weather for many years.

"For me it's got a feeling of desolation, or an attempt to make a home in a desolate place," the video's interviewer says.

But Meek offered a different perspective.

"The other way could look at it is: How wonderful it would have been to see this after weeks and weeks of sledging. We've just come from a modern-day, lovely, warm base. But when this was the only shelter in the landscape, it suddenly takes on a whole new significance and meaning."

Yesterday Briton Preet Chandi triumphantly announced on social media that she had “broken the world record for the longest, solo, unsupported, unassisted polar expedition by a woman.” That all sounds rather impressive to the uninitiated, and of course, skiing solo for over 1,400km in Antarctica is not inconsequential. But any regular follower of Antarctic travel experiences a sense of déjà vu at yet another hairsplitting record claim.

Perishing cold, incalculable remoteness, plunging crevasses, and interminable winds -- Antarctica has a fearsome reputation for the lay public. Yet hundreds of scientists spend the year there without incident. The South Pole fell to one of the very first expeditions to attempt it over 100 years ago. And let's not forget the small number of climbers, skiers, and sledders who successfully (and almost always uneventfully) complete expeditions in various corners of the continent.

Marginal claims - there's a long tradition

Of these Antarctic adventurers, every year a disproportionate number return with a laundry list of claims. Given that most major firsts (e.g. first person to ski to the South Pole solo, first person to cross Antarctica) have already been bagged, adventurers in Antarctica have long manipulated language and used subtle qualifiers to present their expeditions in the most flattering terms.

This is all part of the game to gain media attention, satisfy sponsors, and increase a social media following. Bankrolling any expedition in Antarctica involves big bucks, and not everyone just withdraws the six-figure sum from his or her bank account.

The most infamous recent example of manipulated language is American adventurer Colin O'Brady's controversial 2018 solo ski crossing of Antarctica. As a result of O’Brady’s inflated and inaccurate claims, senior leaders in the polar community came together to create a new system for describing and comparing expeditions -- the Polar Expedition Classification Scheme (PECS). And while the launch of PECS has forced polar travelers to take more care in describing their journeys, some of this season's Antarctic incumbents show that spin remains very much alive.

Colin O'Brady at the South Pole in 2018. Photo: Colin O'Brady

A contrived Antarctic record

Preet Chandi, for example, had set out to ski from Hercules Inlet to the Reedy Glacier on the Ross Ice Shelf, a journey of some 1,700km and 75 days. Chandi struggled to keep up with the required mileage in the soft snow and sastrugi. But after 57 days, she eventually reached the South Pole on January 10.

Once at the Pole, Chandi announced that she would keep sledding onward until January 22 and then be evacuated by plane. Only yesterday did it become apparent why the British adventurer had not stopped at the Pole, despite having no time to reach the Ross Ice Shelf. She wanted to claim that "world record for the longest, solo, unsupported, unassisted polar expedition by a woman." The record was hurried out by her social media team while she was still skiing.

Note that the PECS system does not recognize the term "unassisted." PECS defines this as "a word used previously to describe a journey that did not use wind energy, dogs, or machines for propulsion." But given that new journeys should categorize their mode of travel (e.g. ski, snow kite, etc.) anyway, it's a superfluous term nowadays, simply used to inflate an expedition's purported credentials.

In any case, the plaudits on social media and major news outlets for Chandi's record claim have come rolling in. Even the Prince and Princess of Wales seem to have got in on the act.

Poke around a little, though, and you might begin to feel that this is a little contrived. The previous record holder, Anja Blacha of Germany, had set the distance of 1,381km over 57 days on a complete journey from Berkner Island to the Pole in 2019-2020. In addition, Blacha had no intention of setting a distance record.

Media reports place Chandi as having skied 51km (1,397km over 68 days) further than Blacha and having taken 10 additional days to do so. Those extra kilometers came as part of an incomplete expedition, and as a presumably conscious decision to go that little further simply to craft a record. Considered in that context, it doesn't quite have the same punch.

German adventurer Anja Blacha. Photo: Anja Blacha

Record or not, skiing 1,400Km alone stands by itself

The acid test of the veracity of Chandi’s "unsupported" claim will require clarity on whether Chandi skied on the South Pole Overland Traverse (SPOT) road, a graded, marked road from the South Pole toward the coast. Chandi's tracker does appear to show her skiing near it, although the Reedy route and SPOT road are close together for the first few days out of the Pole. In addition to this, it is now well-accepted in the polar community that a record is not official until verified by PECS.

The British polar adventurer's remarkable achievement of skiing 1,397km solo in Antarctica should stand by itself. Does it really need to be spun to make what was an incomplete expedition sound more noteworthy? Does a marginal improvement on a previous distance warrant trumpeting it as a major accomplishment? And can you claim a record by going further than earlier record holders, who didn’t know they were setting/intending to set a record in the first place?

Note that many potential record claims are provided to adventurers by ALE, the logistics company that organizes most expeditions on the continent. They are in the business of selling their wares. Sometimes that means tantalizing adventurers by pointing out how distinct their expeditions are from others. In Blacha's certification letter in 2020, ALE listed no more than seven potential records, including "the first woman under 30 to ski solo, unsupported, & unassisted to the South Pole."

Changing the goalposts

The other popular spin tactic in Antarctica is altering the original expedition aims to present a journey in a more favorable light. Gareth Andrews and Richard Stephenson had originally planned a "110 day 2,600km coast-to-coast transect of the Antarctic continent" in 2022/23, a journey that they had grandiosely billed as "The Last Great First".

However, at some point in the months leading up to the expedition, this changed to "the longest ever unsupported ski crossing of Antarctica (2,023km) and the first unsupported ski crossing of Antarctica by an Australian or a New Zealander." The duo's intention was to ski from Berkner Island to the Reedy Glacier in 75 days.

However like Chandi, Andrews and Stephenson found themselves behind schedule, and after 66 days and 1,400km, they reached the Pole on January 18. Here they stopped, thus abandoning their original intention of an unsupported ski crossing of Antarctica. Take a look at the expedition website and Instagram page, however: The journey is now labeled as an unsupported Berkner Island to South Pole expedition.

This change of goalposts only creates more confusion for the media and the public. This is a common spin by Antarctic adventurers.

Andrews and Stephenson at the Pole. Photo: Gareth Andrews and Richard Stephenson

Catapulted by a record

The potential boost to reputation and sponsorship that an Antarctic record brings is too much to resist for nearly all of the current generation of Antarctic adventurers. In most cases, records become a springboard to a lucrative speaking career, a book deal, or product endorsements.

Caroline Cote carried out perhaps this year's most impressive expedition, by competently breaking the women's solo speed record from Hercules Inlet to the South Pole by around five days. Note, interestingly, that Cote did not seem to struggle as much as others in the challenging snow conditions. Cote is now represented by a PR agency, which will no doubt leverage the media attention to pull in public speaking gigs, or perhaps to write a book.

But how many formulaic first-person narratives of Antarctic skier versus the great white continent must we endure? What else is left to say? Likewise, there are now hundreds of polar inspirational/motivational speakers. Preet Chandi is doing a great job at inspiring people from underrepresented groups into adventure, but do the many others have such a unique message or story to tell?

Why does it matter?

It should be clear from these examples that Antarctic adventurers strain to sound unique. Every year, another raft of hopefuls repeats the same well-trodden few journeys. When Anja Blacha reached the South Pole in January 2020, she was the 9th woman and 37th person to ski solo and unsupported to the South Pole. Even crossing attempts are now becoming popular, and more are planned for 2023/24.

Consequently, an expedition narrative alone is not compelling enough for the media, for sponsors, and 'For the Gram' anymore. As these many Antarctic adventurers jostle for the limelight, the richness of the experience, the landscape, and the challenge itself become secondary to the need to claim a "record." In the process, other worthy journeys slip from attention. As we reported yesterday, polar veteran Eric Philips skied an entirely new route to the South Pole this season.

Antarctic adventuring has already begun to earn a reputation that any claim goes. Eventually, the endless spin and arbitrarily defined "firsts" and "records" will wear thin for even the most ardent lover of Antarctic travel. Real, world-class accomplishments remain to be done in Antarctica, including a solo and unsupported full ski crossing of the continent. The get-famous-quick adventurers intuitively realize that this is beyond them. But when the day comes that a fit and hyper-competent traveler takes this on and succeeds, will anyone even care?

Health problems -- compounded with the predictably difficult rowing conditions -- forced Fiann Paul, Mike Matson, Jamie Douglas Hamilton, Lisa Farthofer, Stefan Ivanov and Brian Krauskopf to abort the 1,500km Antarctic row they began last week.

On January 11, the veteran six-person team, led by Paul, set out to row from the tip of the Antarctic Peninsula, past Elephant Island, to South Georgia. They wanted to retrace the 1915 voyage of Ernest Shackleton and his crew from Elephant Island to South Georgia. They also wanted to become the first crew to row the Scotia Sea, the first to row the Southern Ocean from south to north, and the first to row from the Antarctic continent.

But problems rose even before the journey even began. The experienced Hamilton had undergone heart surgery recently, then suffered from a lung infection, and was not at peak fitness. Then Farhofer injured herself, affecting how much she could contribute. And almost immediately, Mike Matson had to be evacuated because of extreme seasickness.

Only three healthy rowers

This still left the crew with three injury-free rowers, but it was not enough. To generate enough power against the strong winds, they needed at least two fully fit rowers on each rotation.

So rather than row to the island of South Georgia, they re-routed to Laurie Island, in the South Orkney Islands. This cut their distance from 1,500km to 777km. They concluded their row after six days instead of their planned 18 days.

One of the biggest difficulties was the 100% humidity. With waves crashing over the boat and no way to dry them, everything was soaking wet. Usually, they paddled in conditions that would be considered a storm in any other body of water. Winds averaged 30-35 knots, and waves towered to nine meters.

Exactly 100 years after its original publication, the greatest adventure story ever told gets a 21st-century upgrade.

The tragic tale of Captain Robert Falcon Scott's expedition to the South Pole has been immortalized in many ways, but few have remained as powerful as the 1922 memoir from Aspley Cherry-Garrard.

Cherry-Garrard did not accompany Scott to the South Pole. Rather, his mission was to capture emperor penguin eggs. It nearly killed him and his two companions. But Cherry-Garrard lived to tell the tale, and what a tale it was.

His book, "The Worst Journey in the World", has aged into one of the classics of the adventure genre — and is now available as a beautifully illustrated graphic novel.

Sarah Airriess, a veteran animator at Disney, spent more than 10 years researching Cherry-Garrard's expedition to illustrate a faithful version of the story.

"The personalities of the men, and the science they undertook, are equally as important to understanding the story as the famous feats of exploration," the graphic novel's website said.

Judging by the gorgeous sample pages available online, Airriess has devoted significant time and passion to this project.

'No words could express its horror'

Cherry-Garrard set off on his bizarre and terrible expedition in June 1911. He joined two other members of Scott's larger group: Henry “Birdie” Bowers and Bill Wilson.

Their mission sounded simple: to collect emperor penguin eggs. Unfortunately for them, the birds only laid eggs in the middle of the world's most profound winter. As a result, this side trip from Scott's South Pole ambitions nearly killed all three of them.

The men faced a month of blizzards and temperatures that reached -60˚C — all during the pitch-black of Antarctic winter. It was so consistently frigid that they joked that they considered -50˚ a heat wave. They navigated by the stars, frequently fell into crevasses, and hauled heavy sleds through the sandpaper snow at those temperatures.

Somehow, the small team managed to complete their trek from Scott’s base camp on Ross Island to the penguin colony at Cape Crozier. When they returned with three eggs to Scott's base camp, Cherry-Garrard couldn't continue with Scott. Wilson and Bowers did and perished, leaving Cherry-Garrard the sole survivor of the ordeal.

As for the eggs, the Natural History Museum in London soon decided the eggs didn't provide much scientific value after all. Cherry-Garrard's memoir expresses profound anguish over the journey and its terrible result.

“We had been out for four weeks in conditions in which no man had existed previously for more than a few days, if that," he wrote. "During this time we had seldom slept except from sheer physical exhaustion as men sleep on the rack; and every minute of it we had been fighting for the bed-rock necessaries of bare existence and always in the dark. This journey has beggared our language: no words could express its horror.”

'It's just the best action movie'

Scott's larger expedition to the South Pole proved even more tragic than Cherry-Garrard's penguin eggs mission.

Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen had already beaten the British explorer, arriving at the Pole first. Scott and his companions died of starvation during their return journey, just 11 miles away from a cache of supplies.

As for Airriess and her graphic novel, the illustrator had a simple answer for why the adventures of Scott and Cherry-Garrard have always fascinated her.

"It's just the best action movie," she said in the interview above while visiting Scott's base camp in Antarctica. "There are all sorts of feats of daring-do and narrow scrapes and tobogganing down icefalls, and it's so much fun. I think that's something people sometimes lose when they're reading the words on the page...They're not really seeing the epic adventure cinema that I see in my head when I'm reading it."

The gorgeous samples of Airriess' work certainly reflect her passion for this story. While her website promises wider distribution in the future, you can purchase the first graphic novel in her series here or here.

Airriess has also provided a few free sample pages from her prologue.

For some, the Antarctic season has kicked off. For others, there are still final preparations to complete as they ready to fly out from Punta Arenas to Union Glacier.

Crossings

There are three variations of Antarctic crossings this season. So far, no one is attempting a full crossing of the continent.

Gareth Andrews and Richard Stephenson

Australian Gareth Andrews and Kiwi Richard Stephenson have set off from northern Berkner Island, heading to the Ross Ice Shelf via the South Pole. The pair have an impressive 2,023km slog ahead of them.

They flew out on November 13, stopping off at the Gould Bay Emperor Penguin camp to drop supplies before landing on Berkner Island. Then, on November 14, they put in a full day of skiing, then set up camp.

The next day, they only managed 10km in deep snow. This was the start of a long uphill grind to the Antarctic plateau. “We are happy…we knew it would be a slow start,” they wrote in their daily blog post.

The next day they managed 15km despite fresh snow. The weather looks good, with clear skies and light wind.

Preet Chandi

Preet Chandi isn’t wasting any time. On November 12, she posted from Punta Arenas. By November 15, she was already geared up and at her start point.

“It's pretty cold at the moment and very windy, a lot colder and windier than when I started last year. But last year I started later in the season, and I know the weather can be more temperamental early on. I can really feel my 120kg pulk. Going quite slow at the moment but I’ll gradually build up my mileage as my pulk gets lighter,” she wrote.

Chandi might feel that it has been a slow start, but her tracker shows that she has already knocked off 40km from her 1,600km solo crossing, an impressive start that bodes well.

Six-person Australian team

Emily Chapman, Vincent Carlsen, Jack Forbes, Sean Taylor, Kelly Kavanagh, and Tim Geronimo have arrived at Union Glacier. The weather forced a longer-than-expected wait in Punta Arenas, and they are keen to get going. They hope to fly out to their starting point tomorrow.

Their route plans have changed somewhat. They will now start from Hercules Inlet rather than the Messner Start. They aim to complete their Hercules Inlet-South Pole-Ross Ice Shelf expedition in around 72 days.

Hercules Inlet to the South Pole

Mikko Vermas and Tero Teelahti are still in Punta Arenas making their final preparations. Over the last few days, they have been food shopping and packing their gear for the flight into Union Glacier. This involved dividing 220kg of gear into bags of 25kg or less.

Most of the solo skiers are still in Punta Arenas or Union Glacier. Solo skier Mateusz Waligora is in Antarctica and, weather permitting, is due to fly to Hercules Inlet today. Norwegian Hedvig Hjertaker is still in Punta Arenas and Scot Benjamin Weber flew to Union Glacier yesterday.

There are also at least two speed record hopefuls this season, though neither has set off yet. Canadian Caroline Cote and Brit Wendy Searle each hope to break Swede Johanna Davidsson’s time of 38 days and 23 hours from Hercules Inlet to the South Pole. Searle is due to begin her sprint on December 5, and Cote is also likely to wait out the season’s changeable early weather (and soft snow).

Guided groups from the Messner Start

The 10-person team composed of a mixture of British military personnel and civilians, guided by Canadian Devon McDiarmid, is still packing in Punta Arenas.

After five days of delays, the Ousland Explorers team (guide Bengt Rotmo, Laura Andrews, Mike Dawson, and Marthe Brendefur) arrived at Union Glacier on November 16.

Wrapping up the Messner Start guided groups, two Antarctic Logistics & Expeditions (ALE) teams will also set out on the roughly 1,000km route to the Pole. No word yet on their start dates.

The Antarctic summer is shaping up to be the busiest season since 2011-12. A few familiar names and a swathe of new South Pole hopefuls are gearing up to begin in November or December.

Let’s break down the expeditions that have been announced so far.

Crossings

There are three variations of Antarctic crossings this season. So far, no one is attempting a full crossing of the continent.

Gareth Andrews and Richard Stephenson

Australian Gareth Andrews and Kiwi Richard Stephenson are aiming for a slightly extended version of the journey undertaken by both Colin O’Brady and Lou Rudd in 2018. They’ll set off from northern Berkner Island, head to the South Pole, then make for the nearest "coast", the Ross Ice Shelf, to wrap up their 2,023km route. However, their endpoint is not a true coastal finish, as they plan to end their journey at the inner edge of the permanent ice shelf.

The pair had originally branded their expedition as "The Last Great First", a title that comes up once every couple of years. Instead, they have sensibly rebranded it as Antarctica 2023. Their crossing is certainly not the last great first, though it would be an impressively long journey.

As they are still prominently advertising their expedition as unsupported, it will be interesting to see whether they use the graded, marked road from the South Pole to the Ross Ice Shelf. The road, used by polar scientists, eliminates the need to navigate and provides a smooth run without crevasses or the bumpy sastrugi that skiers dread.

Preet Chandi

Last year, Preet Chandi finished her 1,126km solo expedition from Hercules Inlet to the South Pole in an impressive 40 days. This year, she returns for an even longer slog -- a solo crossing of approximately 1,600km. Presumably, like last year, Chandi is setting off from Hercules Inlet to the South Pole. From there she will continue to the Ross Ice Shelf.

Chandi is flying to Chile soon and plans to set off with a 120kg pulk in early November.

Australian Defence Force

A team from the Australian military (both veterans and serving personnel) will also take on a variation of the same crossing. The six-person team consists of expedition leader Emily Chapman, Vincent Carlsen, Jack Forbes, Sean Taylor, Kelly Kavanagh, and Tim Geronimo.

They hope to complete their Messner Start-South Pole-Ross Ice Shelf route in 72 days.

Hercules Inlet to the South Pole

A host of teams and solo skiers will ski from Hercules Inlet to the Pole.

Mikko Vermas and Tero Teelahti will set out on an unsupported expedition, each pulling 110kg sleds. They hope to cover the 1,130km from Hercules Inlet to the Pole in 40 to 50 days. The pair have some experience, having previously skied to the North Pole in 2006.

Canadian Caroline Cote has set herself an ambitious goal. Cote will travel solo and unsupported, hoping to break the women’s speed record to the Pole from Hercules Inlet. Swede Johanna Davidsson holds the record, set in 2016, with a time of 38 days and 23 hours.

Cote joins at least one more speed record hopeful, Wendy Searle. Searle had a crack at the Hercules Inlet to South Pole speed record in 2020 but missed out on the women's record by about three days.

Other solo skiers include Polish adventurer Mateusz Waligora, Norwegian Hedvig Hjertaker, and Scot Benjamin Weber. Nick Hollis will also set out from Hercules Inlet but it is unclear if he will ski alone.

Guided groups from the Messner Start

Inspire22 is a 10-person team composed of a mixture of British military personnel and civilians, guided by Canadian Devon McDiarmid. They bill their expedition as primarily a scientific endeavor to "explore the metabolic cost of sustained polar travel".

Polar legend Borge Ousland's company, Ousland Explorers, will be guiding a small team from the New Zealand Antarctic Heritage Trust. Bengt Rotmo will guide Kiwi’s Laura Andrews and Mike Dawson (a former Olympian), and Norwegian Marthe Brendefur. The Trust selected the three team members from hundreds of hopefuls aged between 18 and 35 who applied.

Wrapping up the Messner Start guided groups, two Antarctic Logistics & Expeditions (ALE) teams will also set out on the roughly 1,000km route to the Pole.

There's a reason that adventurers continue to marvel at Ernest Shackleton's Antarctic expedition over 100 years later: it lives up to the hype.

Every part of the iconic survival story — from the 1914 struggle to sail Endurance through dense ice floes to the crew's miraculous homecoming two years later — still feels thrilling.

Yet nothing rivals its grand finale: Shackleton and two crew members crossing the "impassable" island of South Georgia to reach a tiny whaling outpost and bring aid to their comrades.

Early this month, a team from the polar exploration group Vinson of Antarctica completed a ski trip across the island, loosely following in Shackleton's footsteps. The small team started and ended in the same places as the explorer, but chose an entirely different route in between.

An alternative route

"I know," mountaineer Stephen Venables said early on, "let’s take the route that Shackleton should have gone. I’ve not done it but I’m sure it’ll be much easier and even more beautiful."

Judging from the expedition's many blog posts, that's exactly what happened. They completed the journey in five days, enjoying excellent weather and good skiing, thanks to their modern equipment.

The team clearly idolizes Shackleton's journey. Yet they seemed more interested in enjoying South Georgia than trying to follow the explorer's exact route.

"Whether this was a better route than Shackleton’s, I’ll never know," expedition member Caroline Hamilton wrote. "What I do know is...we had the most amazing time...I didn’t want it to end. I wished we could have turned around and done it all again."

Shackleton himself would not have been quite so enthusiastic.

Unfinished business

The team might have enjoyed the journey — but that doesn't mean it was easy.

They first tried the Alternative Shackleton Traverse back in 2014. Unfortunately, snow, rain, and 60-knot winds turned them back.

So for Stephen Venables, the trip represented "unfinished business".

Thanks to good weather, this attempt went more smoothly. By day two, "the wind abated, the sun shone and all was sweetness and light," Venables wrote.

The team skied the whole distance, hauling light sleds behind them. They arrived at the Esmark Glacier for their second camp, enjoying a dinner that Shackleton would have envied: soup and risotto followed by hot chocolate with brandy.

Yet the team clearly worked hard to reach its goal, dealing with "impossibly steep cols" that required hours of zigzagging. The hardest sections featured a "serrated ridge of shattered rock".

As a result, crossing the Kohl Plateau to the König Glacier required an "impromptu human funicular" (shown in the photo below).

"No great problem," Venables wrote of the obstacle. "You just have to haul all the pulks [sleds] up one side, secure them with ice screws, then lower them over the other side, down a 10 metres vertical cliff of collapsing masonry. All good fun, but it took four hours before we could get down to a good campsite on the upper König Glacier."

Again and again, team members downplayed the journey's effort by playing up the scenery.

"Everywhere we looked there were brown jagged mountains, covered in snow and ice, and glaciers sweeping down to the sea," Hamilton wrote. "Blue ice, grey ice, white ice - as the light changed through the day, everything looked different."

No doubt the Vinson team enjoyed the journey more than Shackleton enjoyed his. In 1955, a British survey team attempted to recreate the exact mountaineering route that Shackleton took back in 1916. Since then, others have also done the route, but not so many to make it commonplace.

Despite having modern climbing equipment — and actual climbers — team leader Duncan Carse expressed awe for what Shackleton accomplished.

"I do not know how they did it, except that they had to," he wrote. "Three men of the Heroic Age of Antarctic exploration with 50 feet of rope between them — and a carpenter's adze."

After 107 years, the mystery of where in Antarctic waters that Ernest Shackleton's Endurance ended up is over. An expedition team of marine researchers and archaeologists discovered the world-famous shipwreck in the early hours of March 9, 2022. It lay 3,000+ metres down, in the Weddell Sea.

Like other wrecks in polar waters that are deep enough to evade the destructive effects of ice and waves, the vessel is in exceptional condition.

How Shackleton's 'Endurance' Was Found

The team arrived in the region in mid-February aboard the icebreaker S.A. Agulha II. For more than two weeks, the team scanned a 240 sq km region where experts believed the Endurance foundered in 1915. Undersea drones located and documented the largely intact polar ship.

One of the most storied shipwrecks in history, the Endurance became trapped in sea ice on January 18, 1915. Its captain, Irish polar explorer Sir Ernest Shackleton, and his 28-man crew attempted to free the three-masted ship. But by the end of February, temperatures had plummeted, and the ship was frozen in place.

The Sinking of the 'Endurance'

According to the Endurance22 team, pressure from the ice tore away the ship's rudder post and crushed its stern. Shackleton wrote:

...We have been compelled to abandon the ship, which is crushed beyond all hope of ever being righted, we are alive and well, and we have stores and equipment for the task that lies before us. The task is to reach land with all the members of the Expedition. It is hard to write what I feel.

Incredibly, the expedition team survived aboard the frozen Endurance until October 27, 1915. On that day, Shackleton made the decision to abandon it. By November 21, the Endurance finally sank to its watery grave in the Weddell Sea.

Shackleton's great escape

After its sinking, there ensued one of the great survival stories in exploration history. In three lifeboats, all 28 crewmen traveled across sea ice and open water to Elephant Island. From there, Shackleton and a select team of five sailed 1,250km across the stormiest seas on earth in an open boat to little South Georgia.

Shackleton then somehow traversed the mountainous island to the far side, where a whaling station provided help. Even today, that wild alpine crossing impresses the few mountaineers who have managed to duplicate it. Shackleton's remaining expedition members were rescued from Elephant Island on August 30, 1916.

National Geographic broke the news of Endurance's recovery. A documentary of the 2022 expedition is set to air on National Geographic this fall.

Other famous polar shipwrecks

The Endurance marks the latest historic polar shipwreck discovered in recent years. In 2014, after a concerted six-year search, Sir John Franklin's ship, the Erebus, turned up in 11m of water in the Northwest Passage south of King William Island. Because of its location in such shallow water, the Erebus, which sank around 1848, was in much poorer condition than the Endurance.

Two years later, researchers found the Erebus's sister ship, the Terror, in the well-named Terror Bay, off King William Island. It lies 21 to 24m below the surface and is in much better condition than the Erebus.

Less celebrated than the Endurance, the Erebus, and the Terror, Robert McClure's HMS Investigator was abandoned in 1853 after being trapped in the sea ice off northern Banks Island for three years.

The location of the shipwreck was never a mystery, but it lay in such a distant corner of the High Arctic that no one went to look for it until 2010. They found the ship in just eight metres of water, exactly where they expected it to be, in Mercy Bay off northern Banks Island.

Undiscovered but in known locations

Some still-undiscovered polar ships are just waiting for a research crew like the one that found the Endurance or even a passing cruise ship with its side-scan sonar switched on at the right time.

In 1883, the Proteus sailed northern Baffin Bay, between Canada and Greenland, to pick up the U.S. Arctic Expedition under Adolphus Greely. Greely's men had been stationed on northern Ellesmere Island for two years, exploring and doing science for the First International Polar Year. Unlike almost every other polar expedition, they didn't have their own ship. The Proteus had dropped them off two years earlier with a promise to return.

But 1883 was a bad ice year, and the Proteus couldn't get within 300km of Greely's men. Trapped in the ice, amid strong currents, ice floes crushed the Proteus like a walnut. The crew escaped in lifeboats, but Greely's men were stranded, and 19 of 25 died in the aftermath, mostly from starvation. The spot where the Proteus went down is well-known -- just remote. And it lies 350m down, so like the Endurance, it should be well-preserved.

The USS Bear, one of the ships that later saved the few Greely survivors, was found last year off the coast of Massachusetts. It had foundered in a gale decades after that arctic rescue.

Elks are too smart for their own good: Elk in Utah are moving off public land into protected areas during hunting season, then returning when it ends. "It's almost like they're thinking, 'Oh, all these trucks are coming, it's opening day, better move,’” said Brock McMillan, lead author of the new study. He found that the number of elk on public land dropped by a staggering 30% at that time.

This clever behavior has caused issues for landowners, because these large elk populations are wrecking habitat, disrupting farming, and eating food meant for livestock. Meanwhile, hunters are complaining about the lack of elk.

Seasonal hunting keeps the elk population at a manageable size, but this new survival strategy has significantly increased elk numbers. This is not sustainable long-term. Hunters can now apply for further permits to hunt on private land, as long as the landowners agree.

Early humans

The largest human family tree ever created: Scientists have created the largest-ever family tree. It attempts to show how humans today link to each other and to our ancestors. Geneticists studied genome sequences from modern and ancient humans across 215 populations. Computers then showed distinct patterns of genetic variation.

The final map contains almost 27 million ancestors. "We definitely see overwhelming evidence of the out-of-Africa event," said researcher Anthony Wilder Wohns.

The ancient genomes also revealed when different mutations first appeared and how they spread.

Ancient African DNA revels surprises about early humans: Researchers have found the earliest known human DNA from Africa. They studied the remains of six individuals buried in Malawi, Tanzania, and Zambia between 18,000 and 5,000 years ago. They also reanalyzed published data on 28 other individuals in the ancient sites. The research showed major demographic shifts that took place 20,000 to 80,000 years ago. As far back as 50,000 years ago, people migrated within Africa to trade, share information, and find partners.

Drones in science

NASA is flying drones in the Arctic: Scientists have struggled to use drones in the Arctic. The extreme environment -- cold weather, wind, vast open spaces -- has meant that they can’t fly for very long. But NASA has now developed a fixed-winged drone named Vanilla that can remain airborne over the Arctic for several days at a time.

Among other things, it uses radar to measure snow depth on top of the sea ice. Eventually, the drone may also assess how freshwater melt from Greenland and Antarctica is contributing to sea-level rise.

In 2021, Vanilla earned the world record for the longest continuous flight for a remotely piloted aircraft without refueling -- eight days. Though this was in a temperate climate, its builders hope that Vanilla will fly for five days over the Arctic.

Drones reveal whether dolphins are pregnant: Scientists can now use drones to detect pregnant dolphins by measuring the body width of females. A particular pod of dolphins in northern Scotland has been studied for 30 years. Until now, researchers could only tell a successful pregnancy when a calf appeared. “Using aerial photos will allow us to routinely monitor changes in reproductive success," said Barbara Cheney of the University of Aberdeen.

History's largest flyers

New species of Pterosaur uncovered in Scotland: A Ph.D. student in Scotland has discovered a new species of Jurassic pterosaur. Pterosaurs were the first vertebrates to fly and were among the largest flying animals in the earth’s history.

The remains are the largest ever found. It is also the best-preserved pterosaur ever unearthed in Scotland. “Its sharp, fish-snatching teeth still retain a shiny enamel cover, as if it were alive mere weeks ago,” said paleontologist Steve Brusatte. The 170-million-year-old species belongs to a group of early pterosaurs known as Rhamphorhynchidae. The reptile's skull reveals large optic lobes, suggesting that pterosaurs had excellent eyesight.

Even after the early lockdowns lifted, severe travel restrictions aborted many adventures over the last two years. High-altitude climbing continued -- sometimes disastrously -- but arctic expeditions, in particular, all but stopped until this year. As an earlier story pointed out, non-essential outsiders couldn't even visit Canada's Nunavut territory for much of that time. The one notable expedition that did run managed to get an exemption by doing some science en route.

But as the sun returns to the Far North -- it first peeked above the horizon in Grise Fiord, Canada's northernmost community, on February 11 -- the vibe suggests a slow return to normalcy. Arctic expeditions are happening. Others are waiting to see whether Russian entrepreneurs will build the floating ice station Barneo, near the North Pole, again this year. No one knows yet.

Barneo has not run since 2018. In 2019, a now-prescient dispute between Russia and Ukraine cause a last-minute cancellation. Then the pandemic in 2020-21. If the ice station does resurrect this year, expect not only Last-Degree tourist trips, North Pole marathons, etc. but possibly longer efforts that rely on Barneo for pickup.

In the meantime, here is a partial inventory of arctic journeys ongoing or upcoming. We'll update the list as we get further news.

Lena River

Charlie Walker of the UK is currently in Yakutsk, in the coldest part of Siberia, about to trek 1,600km north along the frozen Lena River. We were wondering if Russia's war on Ukraine would cause problems for a Western visitor, but he's there now.

He took his first steps on the Lena's frozen surface two days ago. In a few days, he will begin his long trek to Tiksi, population 5,000, on the Laptev Sea. He insists that it's more than a physical feat: He wants to document the indigenous reindeer herders along the way.

Qitdlarssuaq Returning Home

Pascale Marceau, the partner of veteran arctic traveler Lonnie Dupre, is anxiously watching satellite imagery these days. She hopes that the 1,200km manhauling journey she plans to do with partners Scott Cocks and Jayme Dittmar will come off. They want to ski from Greenland, down the east coast of Ellesmere Island, then across to Devon Island and Baffin Island. Their journey will end at the arctic town of Pond Inlet.

They want to enact the return route of the great Inuit shaman Qitdlarssuaq. He and his party reached Greenland from Baffin Island, stayed many years, and eventually decided to return. Qitdlarssuaq died early in the return trek, shortly after the crossing to Ellesmere Island. Marceau and party want to trace that theoretical return.

But whether they will even begin depends on whether the ice bridge forms between Canada and Greenland. As of February 23, it remained wide open. For hundreds of years, Greenland Inuit used this ice bridge every spring to cross to Canada to hunt muskoxen. But with climate change, its formation in recent years has been hit or miss. They also have a lot of open water to contend with further south as well.

Dupre will join them by dogteam on the Greenland side just as far as Rensselaer Bay, where they will wait for the right conditions to cross.

"If it doesn't form at all... then, well we [will] have a very expensive holiday in Greenland," Marceau said.

Lake Baikal

Usually Lake Baikal hums at this time of year with trekkers hauling their sleds the 650km length of the world's largest lake by volume. It's become a good introduction to arctic sledding because of its moderate length, relative accessibility, and good hauling surface. But whether because of COVID's long tail or Russia's war on Ukraine, we know of only one independent party on Baikal so far: Lukasz Rybicki of Poland, whose drives a bus in London as his day job.

In 2020, Rybicki hoped to set a new speed record but he abandoned his crossing after 300km and six days on the ice. He had suffered a few injuries and fell into the water. Now in 2022, he is giving it another go. The record is about 10 days. Rybicki set off in mid-February dragging a 60kg sled.

The first time I realized that your circulation is highly sensitive at polar temperatures was on my first expedition, in Canada's northern Labrador. It was too cold to stop for lunch, so I held my sandwich in my hand as I skied along, taking occasional bites. By the time I finished eating, I'd frostbitten my index finger, which had lightly held the sandwich.

It was the first and only case of frostbite I've ever had. It wasn't a bad case: a big, purple, water-filled blister that hurt like hell, but which healed over the weeks as I continued.

It taught me a valuable lesson: Polar temperatures are not just colder than ordinary winter temperatures. They're on a different spectrum: Gear, bodies react differently. It's like being an astronaut on another planet.

I'm not talking about -20˚C. That's cold enough, but things behave the same as you're used to. At -40˚, -50˚, they don't always.

Numbness

The second lesson about hypersensitive circulation came years later, when one foot went numb. It did not feel like a dangerous numbness, a frostbite numbness. It felt, as sometimes happens on very cold expeditions, that the peripheral nerves had died. That occurs, usually on the feet, when the skin temperature is around 10˚C for long periods. The nerves near the surface die, and it takes a few weeks or months for them to grow back.

The numbness is a little concerning when it first happens, but it's no big deal. Back home, feeling gradually returns. Numbness becomes tingling, and soon enough, the feet are fine again.

But that wasn't the problem this time. I wondered why the other foot wasn't numb too, so after a couple of days, I checked the problem foot in the tent. It looked fine, although my sock had come down a little and had bunched around the ankle. That little bunching had restricted circulation enough to cause numbness. How do I know? Because a day after I had pulled the sock back up, the feeling returned.

Diabetic socks

Such experiences have made me obsessive about avoiding even normally benign tightness, anywhere. On very cold expeditions, I wear midweight diabetic socks, because those medical socks stay up but do not constrict at all. Some ordinary socks are fine too, but others are too tight at the top.

Most very warm gloves are designed for downhill skiing. Downhill skiers do not ski at -40˚. And here in the Rockies, skiers love to crash through powder. So powder cuffs are useful for them. Not so for those pulling a sled in the polar regions. Sledders do not crash through powder. And those elastic cuffs pinch the wrist slightly and could affect your hands in those weird, wonderful polar temperatures.

So the first thing I do with a new pair of gloves for polar use is to remove the elastic powder cuff with a seam ripper. Sometimes I have to cut open the inside of the glove because the elastic is on the inside. It's a bit finicky, but not hard.

Wristlets

You might think that cold air might leak in through the now-wider mouth of the gloves. Not so, because you should always wear a pair of homemade wool or fleece wristlets if one of your undergarments does not already incorporate them.

The wristlets are thin enough that they do not constrict, and they add about half a layer of warmth. They let you make repairs in the tent barehanded or with just thin gloves on if it's not too cold.

In the summer of 1965, Tété-Michel Kpomassie became the first African to explore Greenland. He was 24 on the day that he stepped onto the dock at Qaqortoq, on Greenland's southern coast. But his arctic journey had actually begun some seven years prior, in the West African town of Lomé, Togo.

Now approaching 81 years of age, Kpomassie is packing up his Parisian apartment and heading back to northern Greenland, where he intends to live out his gloaming.

The story of an African and Greenland

Kpomassie's fabled life story starts with a bit of chance and a book. The young Togolese was 16 when he bought anthropologist Robert Gessain's Les Esquimaux du Groenland à l’Alaska (The Eskimos from Greenland to Alaska) from a small bookshop in Lome. Immediately, the subject captivated him, and within a year he'd run away from home in pursuit of the Arctic.

His trajectory to Greenland was anything but direct. He traveled along the West Coast of Africa, from Côte d’Ivoire in the south to the northern crest of Algeria, eventually crossing into Europe. Ther,e he stayed for some time before disembarking for Greenland via Copenhagen.

"I took my time to step out," he recalled in an interview with The Guardian. "I suspected none would have met a black man before. When I did, everyone stopped talking, all were staring. They didn’t know if I was a real person or wearing a mask. Children hid behind their mothers. Some cried, presuming I was a spirit from the mountains."

Kpomassie found his true home in Greenland's northern reaches, where the Inuit culture that he'd pored over in a book as a boy was very much alive. Over the next 18 months, Greenland's first African transplant learned to ski, mush, ice fish, hunt, and flourish in the tundra.

He returned to Togo in late 1966, reluctant but determined. He adapted the journal he'd kept into a tome, and taught himself several languages through correspondence with friends he'd made on his pilgrimage.

Kpomassie then went on to give numerous lectures about his experience in halls and classrooms throughout Africa and Europe. And he settled down in Paris and raised a family, returning to Greenland on three occasions in that time. "[A]ll the while I knew where I ultimately needed to end up," he said.

His seminal book, "An African in Greenland," was published in France in 1977 and reproduced in English in 1981. It earned him France's Prix Littéraire Francophone International award, also in 1981, and has since been translated into eight languages.

Kpomassie intends to close his story much as it began — with a book and a bit of chance. "I'll have a dog sled and huskies," the explorer remarked. "I’ll find myself a small fishing boat. And here I’ll happily spend my remaining days, and finally find time to write my second book, about my childhood in Africa."

On February 2, ultra-distance Italian cyclist Omar Di Felice hopped on his bike to start a long, cold ride.

In total, Di Felice's westbound route will cover 4,000km of arctic terrain, from Kamchatka to Alaska. His Arctic World Tour will include stages in Scandinavia, Iceland, and Greenland. He hopes to inspire people to travel by bicycle and point out the impact of fossil fuel emissions on arctic landscapes.

Di Felice's route and trip details

Di Felice hopes to complete the cycling in three weeks. Currently, GPS tracking shows that he's already covered a good chunk of the 800km he planned to ride between the capital of Petropavlovsk-Kamchatskiy and Ust'-Kamchatsk.

He will then proceed to Murmansk, Russia, near the Norwegian border. Stages between Tromsø, Norway, through Finland and Sweden, will take him another 1,500km. Di Felice will then go island-hopping; short stages in Svalbard, Iceland, and Greenland follow.

Finally, he will travel (by some means other than cycling) to Whitehorse, Canada, for a long final stage ending at the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta in Alaska.

Di Felice has a specially-outfitted touring bike to crunch through the snow. Along with his 4,000km on the bike, he's imposing a rule to supply and support himself locally when possible. Even if it's well below zero, he plans to pitch camp if he can't find indoor accommodation.

You can follow Di Felice via social media channels. He plans frequent updates, with episodes featuring locals and arctic scientists. The ultra-cyclist wants to highlight his interview subjects' experience living in areas under changing climatic circumstances.

Di Felice has previous experience with cold-weather cycling. He already circumnavigated Iceland this winter via the 1,294km Ring Road. The trip took him 19 days.

A passion for the natural world drives many of our adventures. And when we’re not actually outside, we love delving into the discoveries about the places where we live and travel. Here are some of the best natural history links we’ve found this week.

New images of the heart of the Milky Way: This week, we saw a new image of the heart of our galaxy. Unlike any previous image of outer space, it looks like a piece of modern art. The MeerKAT radio telescope in South Africa combines 200 hours of observation and 20 separate images over three years to produce this accidental oeuvre.

The satellite captured radio waves from different astronomical events. The bottom right-hand side shows the remnants of a supernova, while the bright orange eye in the center is a supermassive black hole. Stronger radio signals register in red and orange. Fainter zones are gray; darker shades indicate stronger emissions.

Accelerated electrons gyrating in a magnetic field create the vertical filaments, but there is no known engine to accelerate the particles. “They were a puzzle. They’re still a puzzle,” says astrophysicist Farhad Yusef-Zade.

Tiger sharks' quest for cooler oceans may land them in hot water

Tiger sharks are migrating further north: Waters off the northeastern U.S. are warming rapidly. Since the 1980s, the temperature has increased by 1.5˚C. This has rewired the marine ecosystems in the area. Some species have moved into new areas, others have disappeared altogether.

The warmer water has even affected the area's apex predator, the tiger shark. Tiger sharks are migrating 430km further north than they did 40 years ago. This may have an indirect effect on the shark's population. Though numbers are currently stable, the new pattern moves them out of marine protected areas. “Tiger sharks reproduce and grow slowly, which makes them more vulnerable to threats like fishing,” explains researcher Neil Hammerschlag.

Switzerland covered in 3,000 tonnes of nanoplastics each year: Across the Alps and lowlands, 3,000 tonnes of nanoplastics cover Switzerland each year. Researchers took snow samples from the top of one peak, Hoher Sonnblick, every day. They analyzed the contamination levels and used weather data to track the origin of the tiny plastic particles. One-third came from urban areas within 200km. Some came from the oceans, where the plastic drifted great distances in the air because of spray from waves -- amazing that this reached such a landlocked country. Nanoplastics can pose a serious health threat. Particles smaller than 10 microns can enter our lungs and eventually our bloodstream.

The Antarctic Paradox

Unpredictable sea ice behavior around Antarctica explained: Sea ice loss in the Arctic follows predictable patterns and models, but the ice around Antarctica is more capricious. Antarctic sea ice remains fairly constant, despite warming temperatures. This is known as the Antarctic Paradox, and scientists have been at a loss to explain it.

A new study suggests that ocean eddies may delay sea-ice loss. Previous models suggested that the eddies drove more heat toward Antarctica than they actually do. In fact, the eddies neither help nor hurt. This means that the amount of heat transported north is higher than previously thought, and the Southern Ocean is not warming as quickly as expected.

Greenland ice sheet lost enough water in 20 years to cover U.S.: Since 2002, the Greenland ice sheet has lost 4,700 billion tonnes of ice from global warming. This is enough water to submerge the entire United States. Overall, it has caused a 1.2cm sea-level rise. The climate is warming faster in the Arctic than anywhere else on the planet. Satellite images show the most affected areas are the arctic coasts, especially west Greenland. “The ice is thinning, the glacier fronts are retreating in fiords and on land, and there is a greater degree of melting from the surface of the ice,” said the Danish study.

The International Space Station shows its age

The end of the International Space Station: The 30-year-old International Space station is starting to show its age. Astronauts regularly report technical problems, cracks, and leaks. NASA will keep the ISS running until 2030, but plans to repurpose it for private and commercial missions. They are predicting that the station will cease being useful in January 2031. This is when it will start to fall back towards Earth. Its size means it will not burn up in the atmosphere. NASA will need to control its fall using propulsion built into the station, and by other vehicles. They will guide it to touch down in the South Pacific Ocean, the furthest point on Earth from land.

In the last week, haunting images of polar bears peering out from abandoned cabins in the Russian Arctic have gone viral. ExplorersWeb spoke to Dmitry Kokh, the tech entrepreneur-turned-photographer who took the images.

The 41-year old Kokh runs a successful tech company in Moscow. The popularity of his photos has surprised even him. He has had to take a vacation from his day job, because of the endless requests to buy prints of the bears.

Enjoys the company of animals

Kokh is an introvert by nature. He seems to feel more comfortable around animals than people. He tends to spend most of his time traveling to the wildest, least accessible places.

Last August, he and a friend traveled 2,000km on a small ice-class sailing yacht to Russia’s Wrangel Island, known as a polar bear maternity ward. Kokh hoped to capture the white bears up close.

The two adventurers slowly made their way along the coast, past humpback whales, sea lions, seals, and birds, across a constantly shifting ice-and-water puzzle. They stopped in deserted bays, saw plenty of brown bears, and went scuba diving in the freezing waters of the Chukchi Sea. As you can see from his website, Kokh is also a serious underwater photographer.

Eventually, the sea ice thickened. It was early fall, the best time of year to travel up there because the ice is at its minimum, and they were not expecting this obstacle.

One day, a storm caught them in the middle of the Chukchi Sea and forced them to take refuge behind a small island named Kolyuchin. Today, Kolyuchin is entirely abandoned, but it was a thriving community when I first visited it 36 years ago as Pravda’s polar reporter.

The story of Kolyuchin Island

Kolyuchin’s name tells its history. Kulusik means a “field of sea ice” in the Chaplino Eskimo dialect, while Kuvluch’in means “round” in Chukchi. Indeed, from above, Kolyuchin looks almost round, and since ice and snow cover it for nine months a year, it is almost always white.

For millennia, Kolyuchin has been a hunting ground both for the Chukchi and the Yupik, who shared the island. Some lived all year round in a small settlement, while others migrated here in the summer to hunt walruses, seals, and polar bears, and to collect berries, mushrooms, and eggs.

Then, in 1934, at the height of Soviet colonization of the Arctic, a polar meteorological station was built on the island. This was not an easy ordeal for those assigned there. Logistics were horrible, and there was no fresh water. By then, the indigenous name of the island had become russified into Kolyuchin, which literally means “a prickly place”.

The indigenous elders who grew up on the island told me another story of Kolyuchin’s name. According to their version, Keglusin means a lonely maritime giant, or rather, a lonely adult walrus who had lost its mother too early, in infancy. It grew up to be mean and aggressive, attacking everyone.

The island was apt for such a legend, because of its humongous walrus aggregations. They gather in the thousands on the rocky beaches.

Kolyuchin abandoned

Time stopped on Kolyuchin in 1992, soon after the collapse of the Soviet Union. Because of lack of funding, the polar station, like many others in the Arctic, shut down. Today, Kolyuchin is wilderness with a few derelict buildings. Occasionally, locals come here by boat or dogsled from nearby Nutepelmen, 14km away, to hunt.

'We noticed a movement in the window'