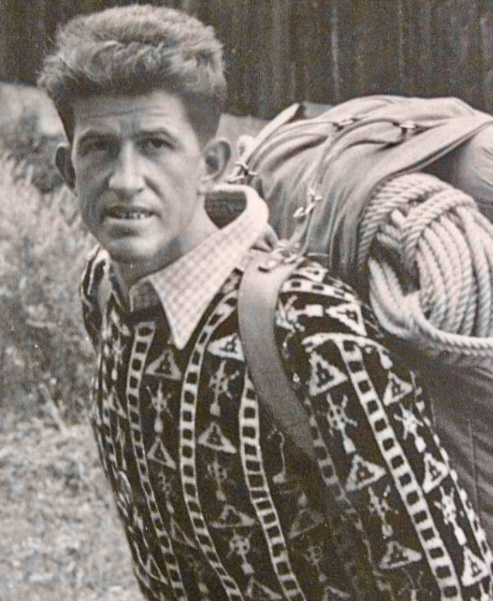

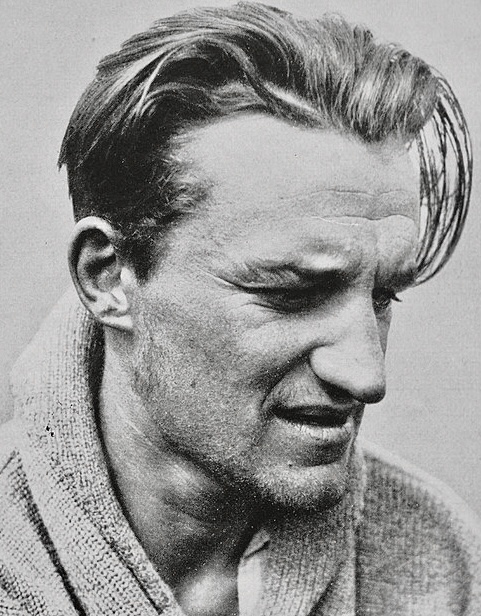

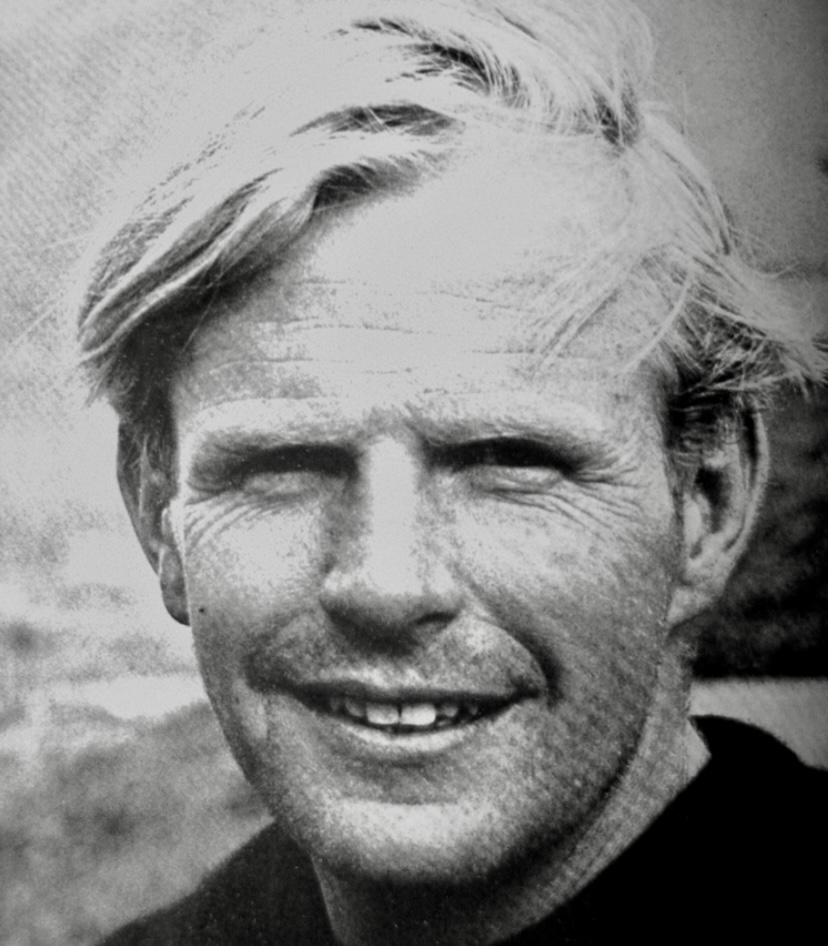

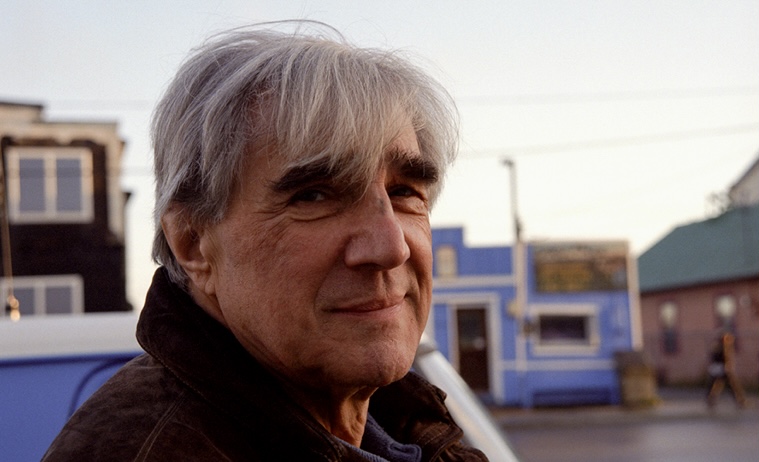

Today, July 25, would be the 104th birthday of Lionel Terray. The celebrated French alpinist climbed routes from the Alps to the Himalaya to the Andes, and also wrote one of the all-time great mountaineering books, Conquistadors of the Useless.

Early years

Lionel Terray was born on July 25, 1921. Growing up in Grenoble near the French Alps, Terray discovered mountaineering and skiing as a child. A conversation with his mother, who dismissed climbing as a stupid sport involving scaling rocks with your hands and feet, sparked his curiosity.

By age 12, Terray was climbing peaks like the Aiguille du Belvedere and the Aiguille d’Argentiere with his cousin. By 13, the talented youngster was leading climbs. But Terray’s love for the mountains caused problems; he got kicked out of one boarding school and ran away from another to pursue ski racing. With little family support, he got by on his own. Skiing was Terray’s first love, and as a teen, he won prizes in competitions, which gave him some money.

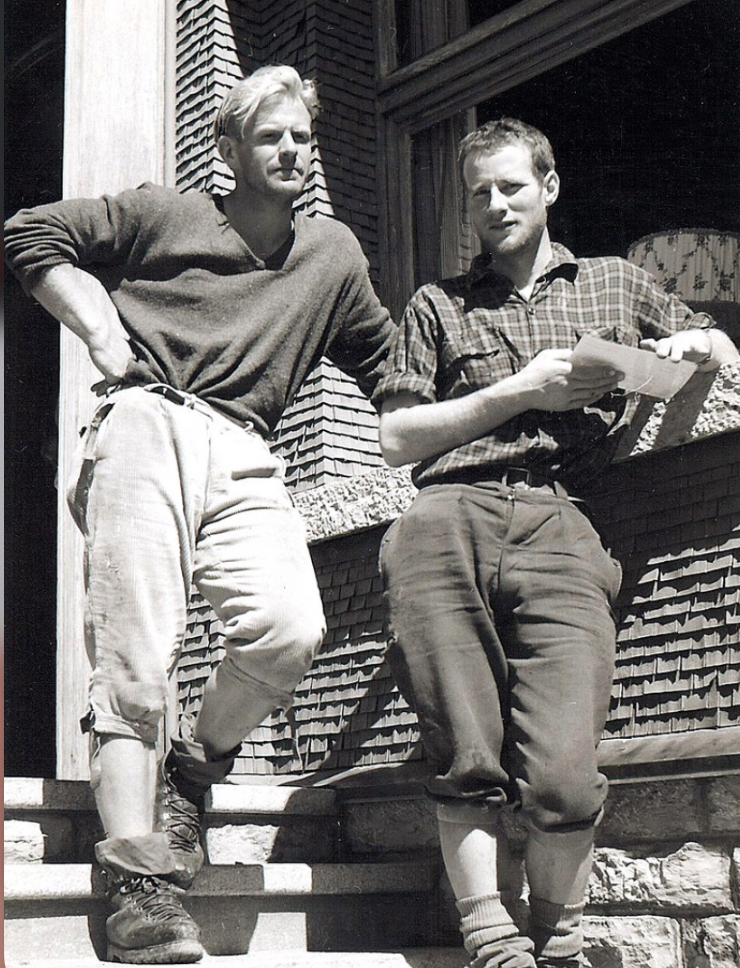

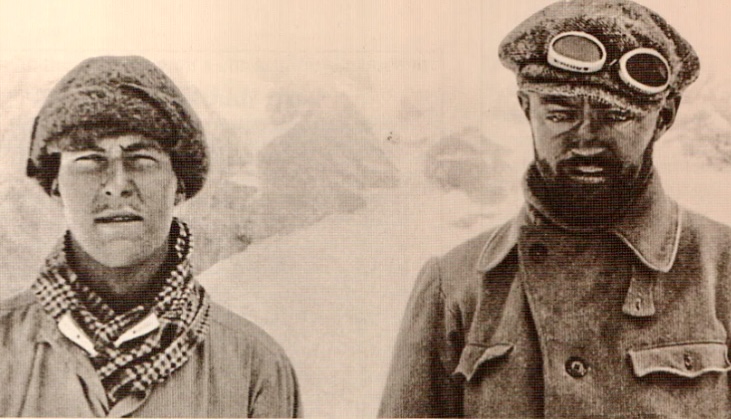

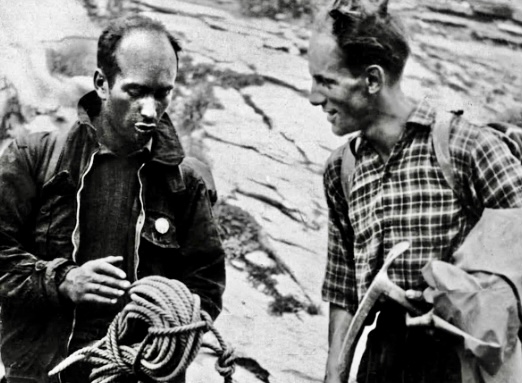

In 1941, during World War II, Terray joined Jeunesse et Montagne, a military program that kept him in the mountains. There, he met lifelong friends and climbing partners Gaston Rebuffat and Louis Lachenal.

In 1942, Terray carried out the first ascent of the west side of Aiguille Purtscheller. He also climbed the difficult Col du Caiman. From 1943 to 1944, Terray served in a high-mountain military unit. In 1944, he joined the French resistance, using his mountain skills against the Nazis.

Terray knocked off other notable first ascents, such as the east-northeast spur of the Pain de Sucre and the north face of Aiguille des Pelerins with Maurice Herzog in 1944.

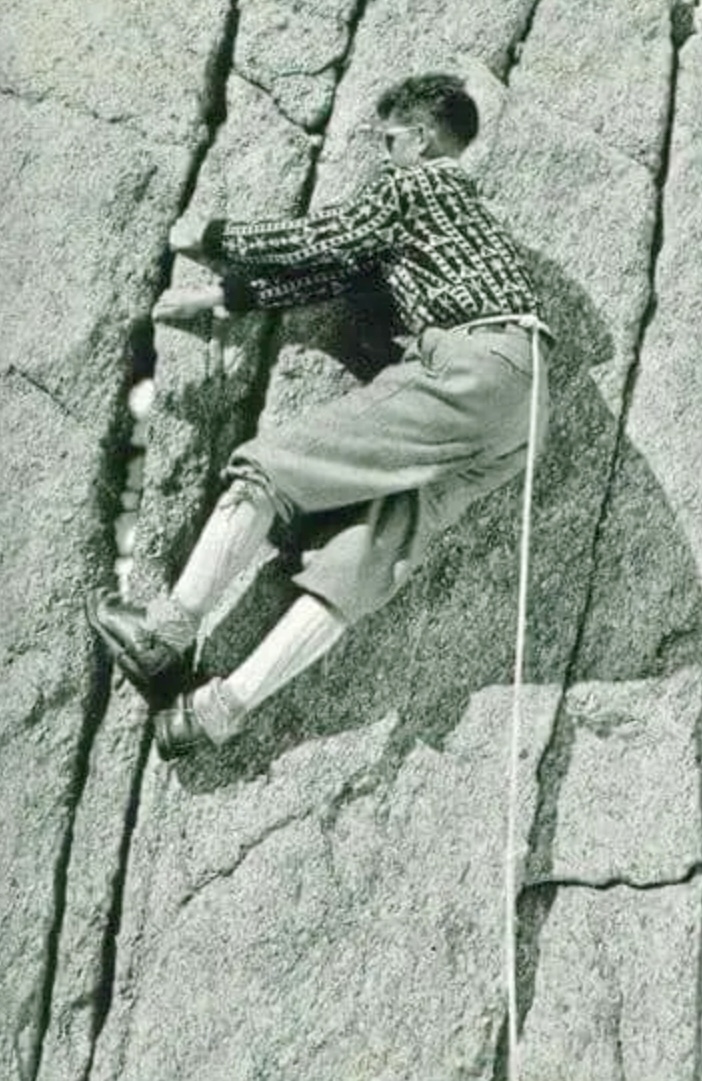

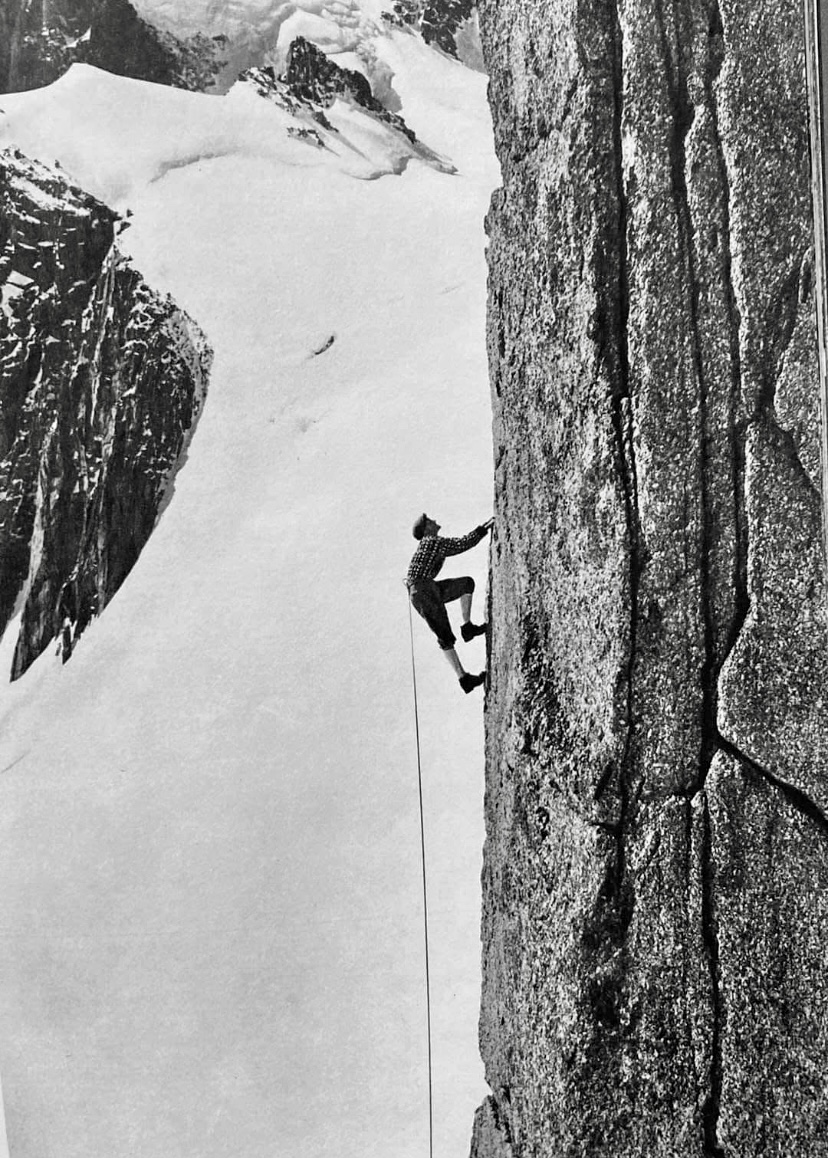

A rising star

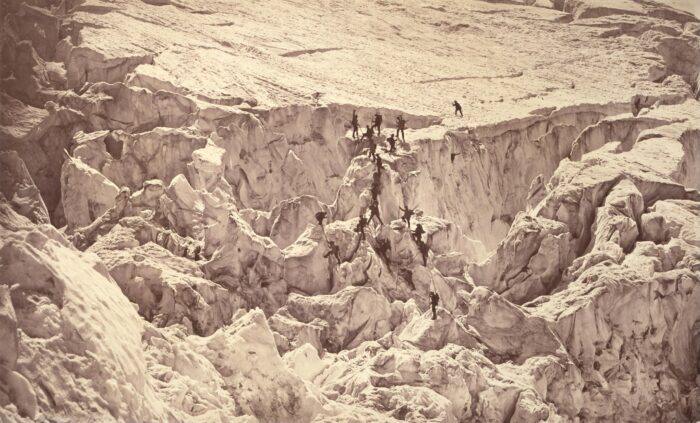

After the war, Terray became a mountaineering instructor and settled in Chamonix as a freelance guide. With Lachenal, he did some of the Alps’ most difficult routes, including the Droites’ north spur in only eight hours in 1946, the Walker Spur of the Grandes Jorasses in 1946, the northeast face of Piz Badile, and the north face of the Eiger in 1947 (the second-ever ascent). Terray's speed and skill earned him a reputation as a climbing prodigy.

A rescue attempt on Mont Blanc

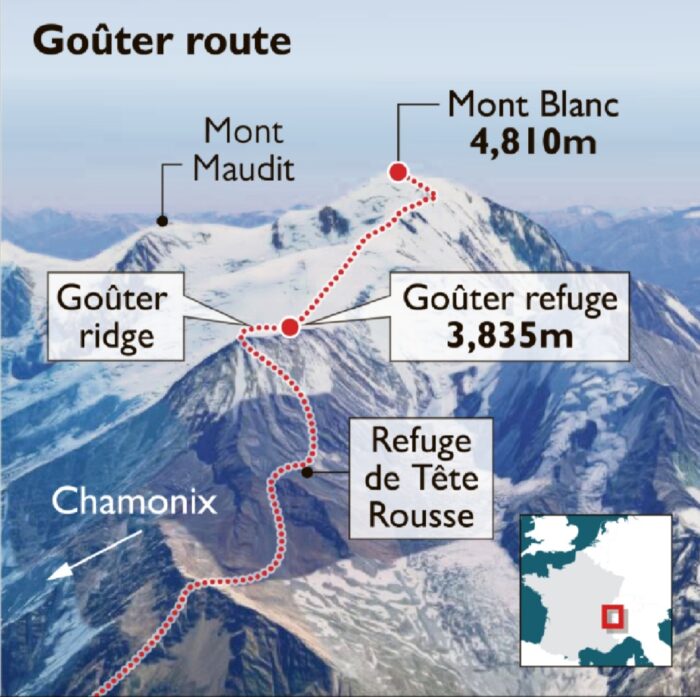

In late December 1956, Lionel Terray took part in a rescue attempt on Mont Blanc’s Grand Plateau. At about 4,000m, young climbers Jean Vincendon and Francois Henry were stranded after a failed attempt on the Gouter Route, a popular 1,800m climb to Mont Blanc’s summit.

On December 22, a blizzard caught Vincendon and Henry near the Vallot Hut at 4,362m. Freezing and frostbitten, they couldn’t descend. Terray, now a Chamonix guide, defied the Compagnie des Guides’ decision to postpone a rescue because of the extreme risks of strong winds and freezing temperatures.

Terray’s team battled brutal weather for two days but couldn’t reach the climbers. A military helicopter, attempting a parallel rescue, crashed near the Vallot Hut, stranding its crew. Terray’s group retreated, exhausted, as conditions worsened.

French Army instructors finally reached Vincendon and Henry in early January, but found them near death from exposure and frostbite. Evacuation was impossible, and both climbers died.

Terray’s rescue effort led to his expulsion from the guides’ organization, sparking controversy in Chamonix.

Eiger rescue

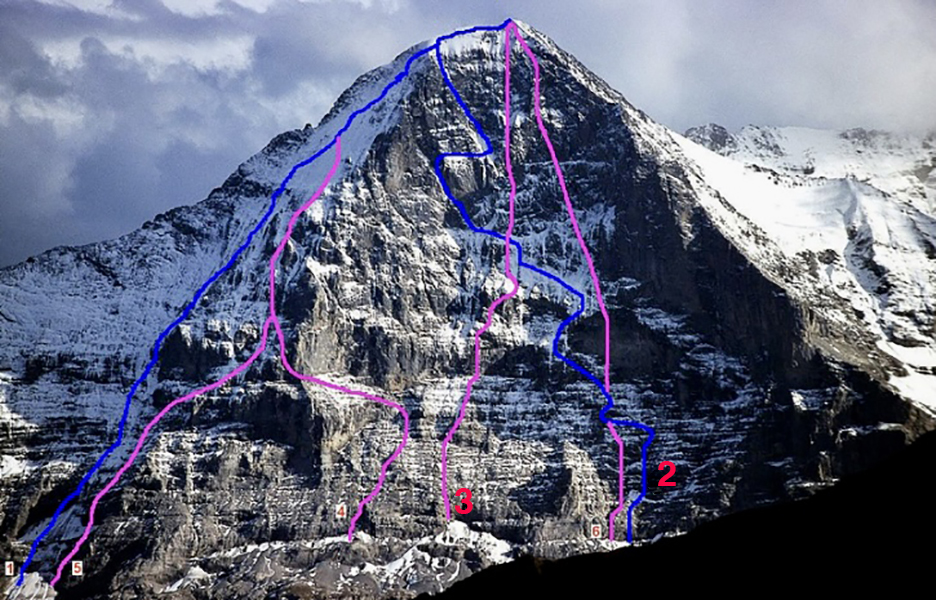

In the summer of 1957, Terray took part in a complicated rescue on the Eiger’s North Face in the Swiss Alps. Two Italian climbers, Claudio Corti and Stefano Longhi, were stranded after an avalanche hit their team during an attempt on the notorious Nordwand. The route, known for its steep ice, rockfall, and brutal weather, had already killed their partners, and Corti was injured.

Terray, then 35, joined a multinational rescue team at Kleine Scheidegg. The climbers were stuck near the Difficult Crack, at around 3,300m. Terray, with German climbers Wolfgang Stefan and Hans Ratay, ascended via ropes and pitons. They battled harsh winds and -20°C temperatures. After two days, they reached Corti, who was hypothermic but alive, clinging to a ledge. Longhi, lower down, was too weak to move. Terray secured Corti with ropes, and the team lowered him 600m to safety. Longhi, barely conscious, died during the descent when his rope jammed.

The effort, involving 50 people, was one of mountaineering’s greatest rescues.

Other historic climbs

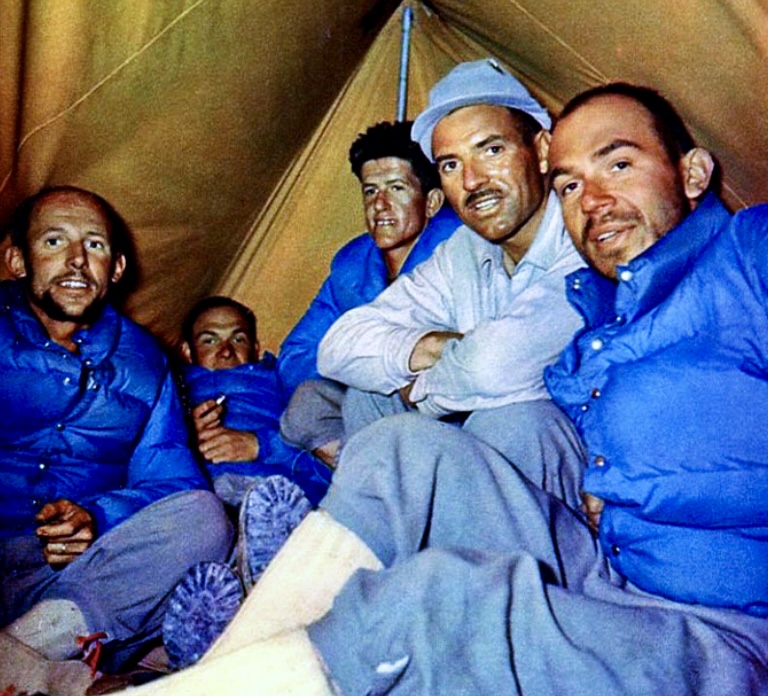

Terray’s ambition took him beyond the Alps. In 1950, he joined Maurice Herzog’s expedition to 8,091m Annapurna I in the Himalaya, the first confirmed ascent of an 8,000m peak. Terray and Rebuffat's efforts, alongside one of the Sherpas, were crucial to helping the frostbitten Herzog and Lachenal descend safely. The climb brought global fame for the French team.

In 1952, Terray and Guido Magnone made the first ascent of Cerro Fitz Roy in Patagonia. That year, Terray also climbed 6,369m Huantsan in Peru with Cees Egeler and Tom De Booy.

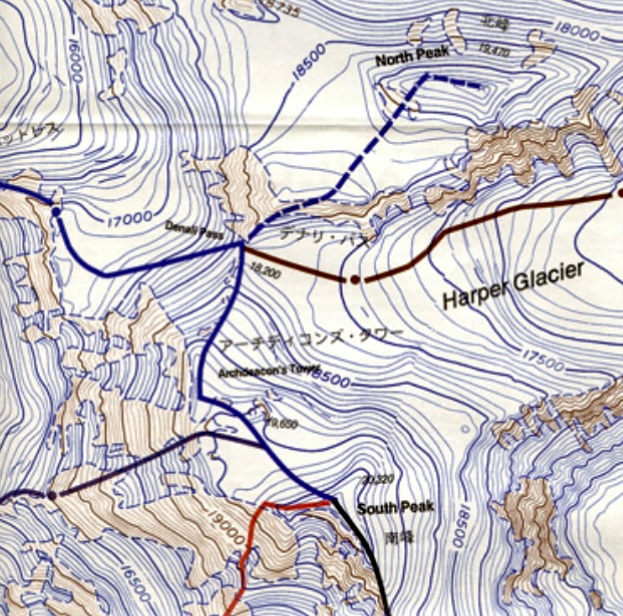

In 1954, Terray summited 7,804m Chomo Lonzo with Jean Couzy, paving the way for their legendary 1955 first ascent of 8,485m Makalu. In 1962, Terray led the first ascent of 7,710m Jannu in Nepal, and in the summer of 1964, he led the first ascent of 3,731m Mount Huntington in Alaska.

In Peru, Terray made first ascents of peaks like 6,108m Chacraraju, considered the hardest peak in the Andes at the time, along with 5,350m Willka Wiqi, 5,428m Soray, and 5,830m Tawllirahu.

Conquistadors of the Useless

In 1961, Terray published Les Conquerants de l’inutile (Conquistadors of the Useless), a memoir that blends vivid accounts of his climbs with reflections on the purpose of mountaineering. The title captures his view that climbing, though seen as pointless by some, was a noble pursuit. The book, translated into several languages, remains a classic.

A tragic end

On September 19, 1965, Terray and his friend Marc Martinetti died in a climbing accident in the Vercors massif near Grenoble. Terray was just 44.

The pair was descending the Gerbier, a limestone cliff in the Vercors range, after completing a route. They were roped together when their rope -- likely weakened or damaged -- snapped. They fell more than 200m to the base of the cliff. Both climbers died on impact. Chamonix mourned deeply, and his funeral drew figures like Herzog, Rebuffat, and Leo LeBon.

"He was to many a great and dear friend, and all those who paid him tribute before he was laid to rest in the Chamonix Cemetery, among them hardened mountain climbers, wept like small children. To the French climbing world, especially the younger generation, his absence represents an irreplaceable loss, as he was the hero of their dreams, and could hold an audience breathless as no one ever has been able to," Lebon wrote in the American Alpine Journal.

Terray’s legacy lives on through his climbs, rescues, and writings. His son, Nicolas, is a mountain guide. Known for his red beanie and sunglasses, Terray appeared in films like Etoile du Midi, La Grande Descente, and Stars Above Mont Blanc.

You can watch Etoile du Midi below, with the option of automatic subtitles:

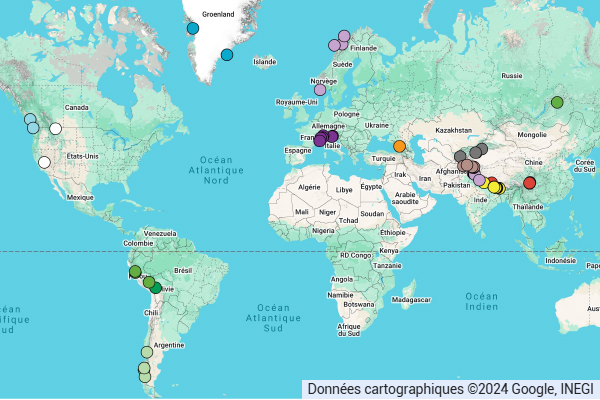

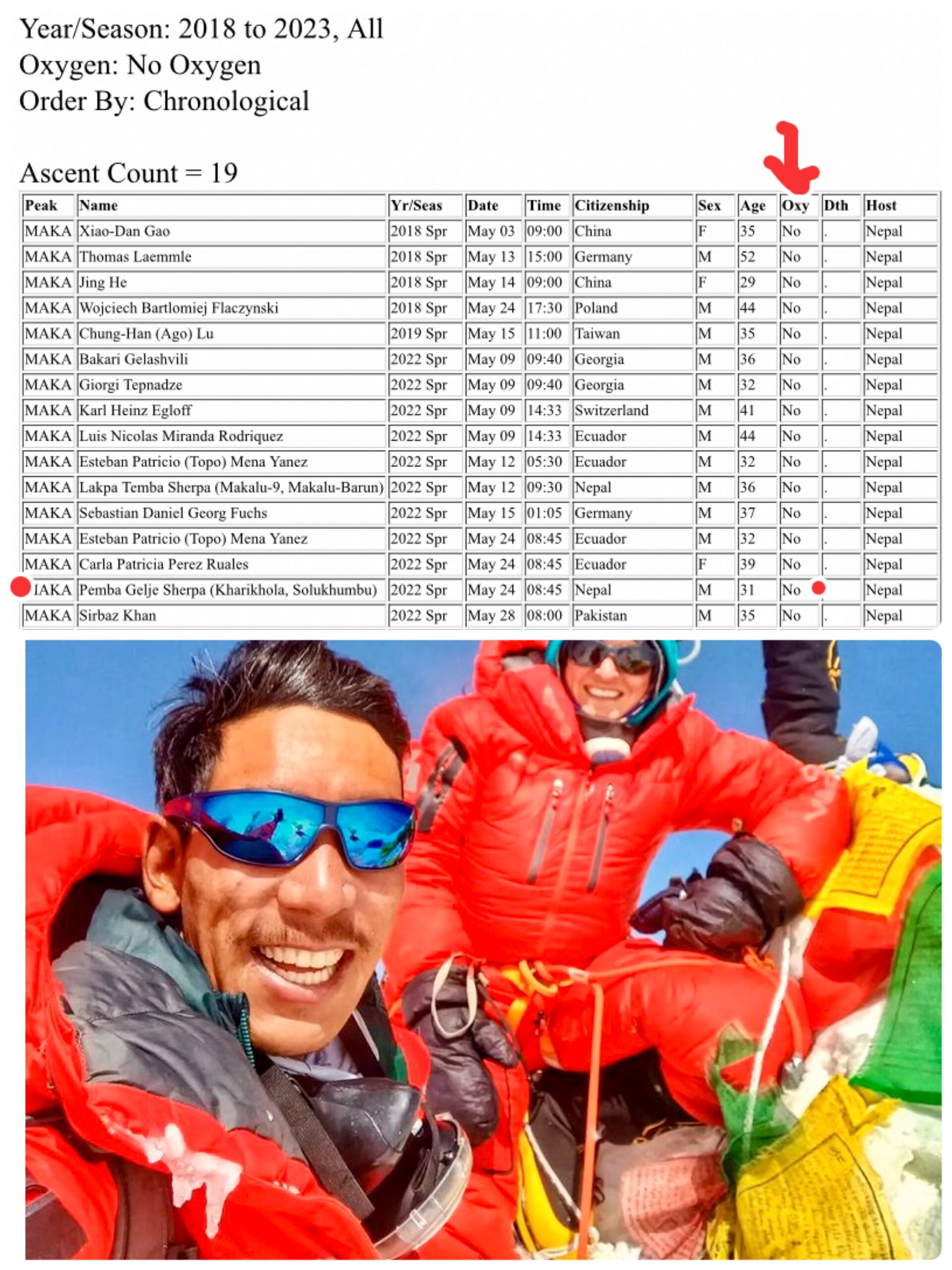

Kim Chang-ho was a South Korean mountaineer who summited the 14x8,000'ers without supplemental oxygen in record time. He pioneered numerous new routes and first ascents on 6,000m and 7,000m peaks. Today, we revisit his most notable climbs.

Early years

Most sources list Kim's birthday as September 15, 1969, but mountaineering historian Bob A. Schelfhout Aubertijn confirmed that Kim was born on July 13, with confusion arising from the Korean age system.

In 1988, Kim began studying International Trade at the University of Seoul. Inspired by Alexander the Great's exploits, Kim started climbing with the university’s Alpine Club.

His frequent expeditions delayed his academic progress, and he didn’t earn his Business Administration degree until 2013. Kim viewed his humanities studies as a way to enrich his climbing. He believed that understanding culture and history deepened his connection to the mountains.

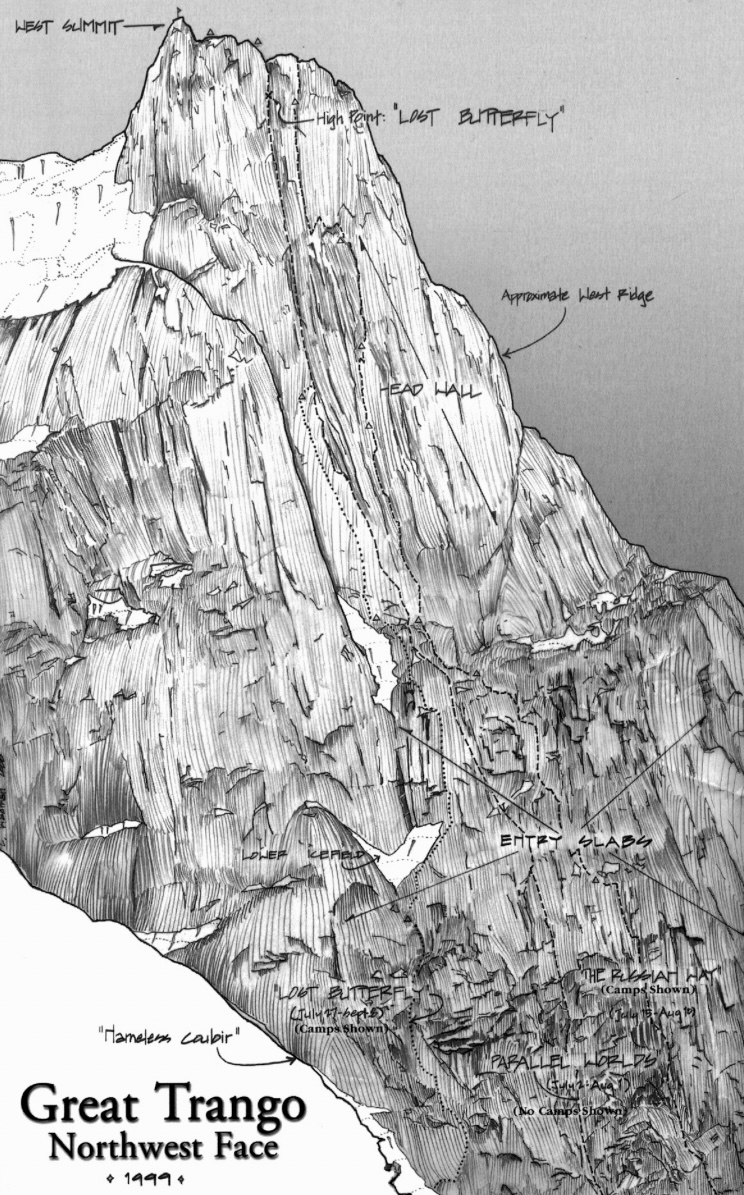

By the 1990s, he was already tackling rock-climbing routes up to 5.12. Early expeditions to the Karakoram, including attempts on 6,286m Great Trango in 1993, and 7,925m Gasherbrum IV in 1996, revealed his bold -- sometimes reckless -- ambition. On Gasherbrum IV, he reached 7,450m but faced a sheer rock face without protection, instructing his partner to release the rope if he fell.

Exploration of northern Pakistan

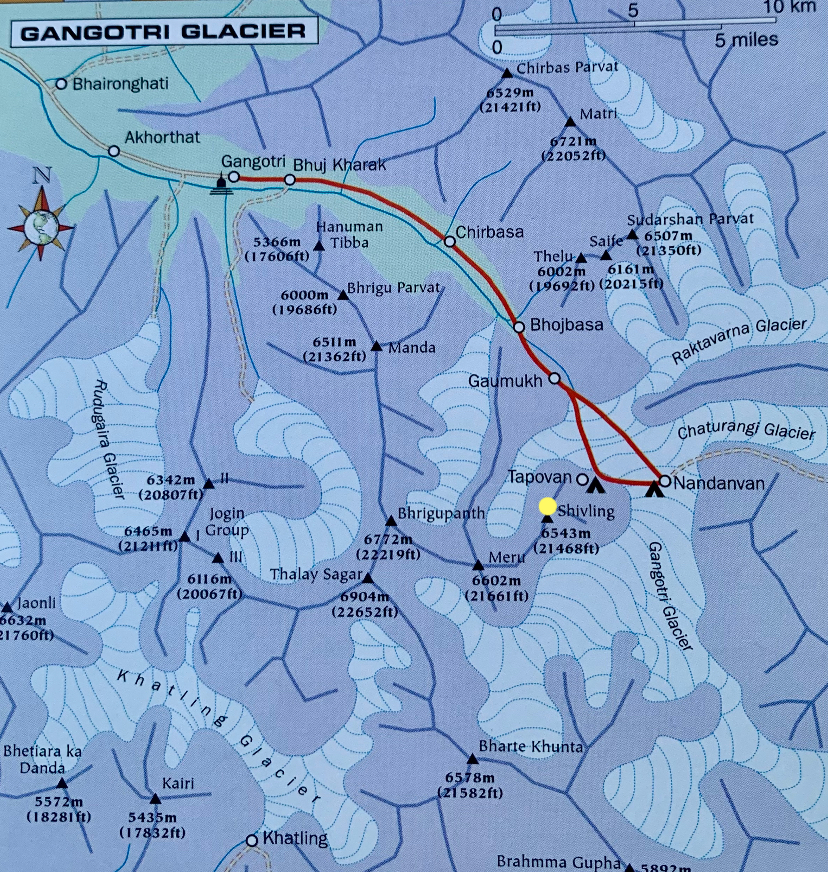

Between 2000 and 2004, Kim embarked on solo trips in northern Pakistan’s Karakoram, Hindu Kush, and Pamir ranges, prioritizing discovery over summits. As detailed in the 2023 American Alpine Journal, he surveyed glacial valleys, documented hundreds of unclimbed peaks, and built relationships with local farmers and herders. These solitary treks were driven by a desire to understand the geography, culture, and history of the regions.

Kim’s journals reveal a meticulous approach, with photographs and descriptions of potential routes forming a database that remains a valuable resource for climbers. His interactions with locals shaped his climbing decisions, ensuring cultural sensitivity in his choice of peaks. This period of exploration laid the groundwork for his later ascents, blending adventure with respect for the human and natural contexts of the mountains.

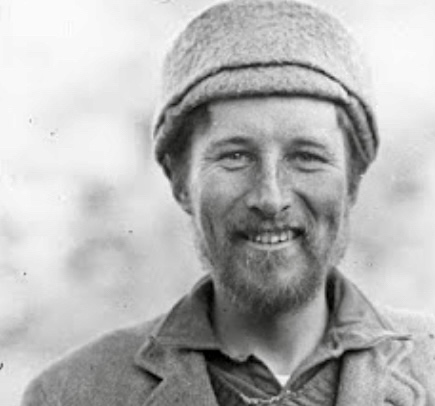

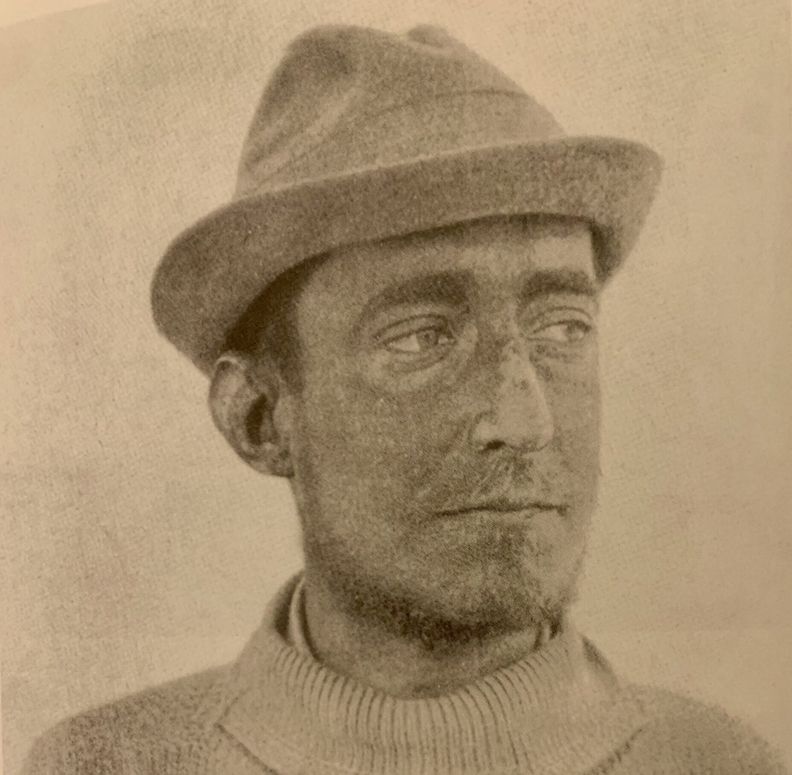

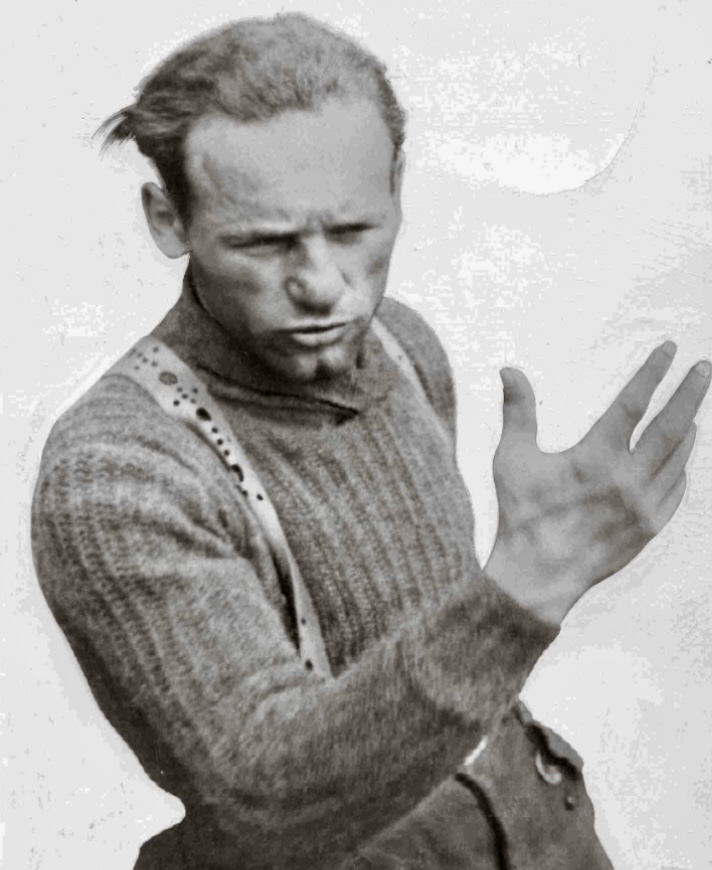

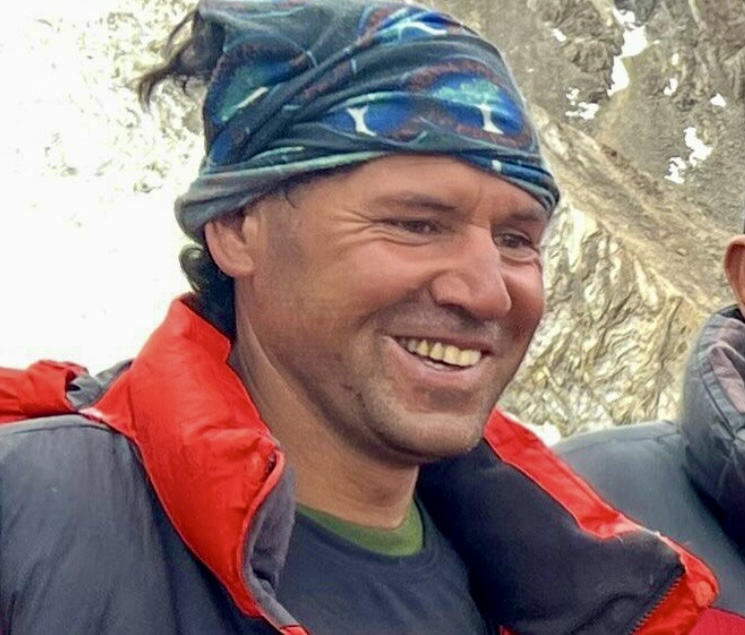

Photo: Kim Chang-ho

Four first ascents of 6,000m peaks

Kim’s explorations in Pakistan led to a series of remarkable solo first ascents in 2003, when he was 33. The American Alpine Journal documents four solo climbs of 6,000m peaks in the Hindu Raj and Karakoram ranges.

He carried out the first ascent of 6,105mm Haiz Kor in the Thui Range of the Hindu Raj, by a challenging route via the southeast face and south ridge through a complex icefall.

Kim also made first ascents of 6,225m Dehli Sang-i-Sar in the Little Pamir, 6,189m Atar Kor in the Hindu Raj, and 6,200m Bakma Brakk in the Masherbrums.

Dehli Sang-i Sar from the southwest, showing the general line of Kim Chang-ho's solo ascent along the upper east ridge in 2003. Photo: Kim Chang-ho

Mastering 7,000’ers

In 2008, he led the first ascent of 7,762m Batura II, though the expedition’s use of fixed ropes drew criticism, prompting him to refine his lightweight approach.

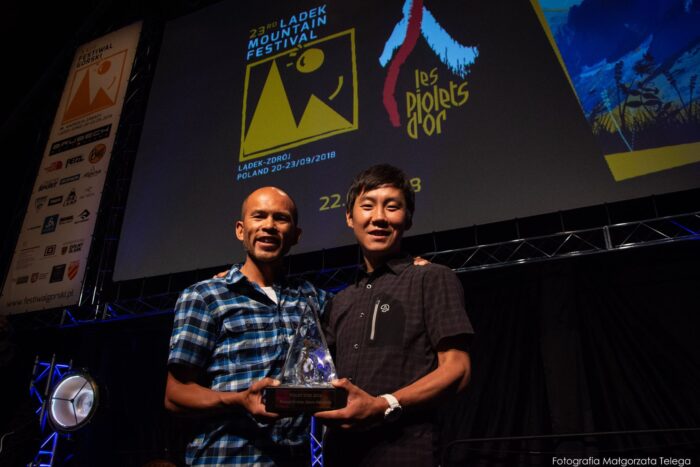

In 2012, Kim and An Chi-young made the first ascent of 7,092m Himjung in Nepal, climbing via its southwest face. The expedition earned them the Piolet d’Or Asia Award.

In 2016, Kim and two partners opened a new 3,800m alpine route on the south face of 7,455m Gangapurna in Nepal. Described by the 2017 Piolet d’Or committee as "bold and lightweight," it earned an Honorable Mention, marking a historic recognition for Korean climbers.

During the Gangapurna expedition, Kim and his partners also attempted the south face of unclimbed Gangapurna West, where they reached the summit ridge.

One year after Gangapurna, the tireless Kim led an expedition to Himachal Pradesh in India, aimed at fostering a younger generation of Korean climbers and developing their skills and experience. The team made the second ascent of 6,446m Dharamsura, and climbed 6,451m Papsura via a direct route on the south face.

Choi Seok-mun and Park Joung-yong, climbing partners of Kim Chang-ho, approach the summit of Gangapurna. Photo: Korean Way Project

Summiting 8,000'ers

Kim summited all 14 of the world’s 8,000m peaks without supplemental oxygen, in record time.

Starting in 2006 with the Busan Alpine Federation’s Dynamic Hope Expedition (led by Hong Bo-Sung), Kim and a small team relied on minimal support, avoiding Sherpas and oxygen. Kim studied geography and history to learn more about his routes.

Kim completed the 14x8,000'ers in 7 years, 10 months, and 6 days, setting a record for the fastest completion without oxygen at the time. He surpassed Jerzy Kukuczka's record by one month.

Kim didn't set out with the explicit goal of climbing the 8,000'ers so quickly. His pursuit was primarily driven by his passion for mountaineering and a desire to climb these peaks in a pure, lightweight style.

Kim ascended three 8,000m peaks twice: Nanga Parbat, Gasherbrum I, and Gasherbrum II.

Among his 8,000m climbs, his south-north traverse of Nanga Parbat in 2005 and his sea-to-summit ascent of Everest in 2013 deserve special mention.

The south face of Gangapurna, showing (in red) the Canadian Route (1981), and (yellow) the Korean Way (2016). Photo: Korean Way Project

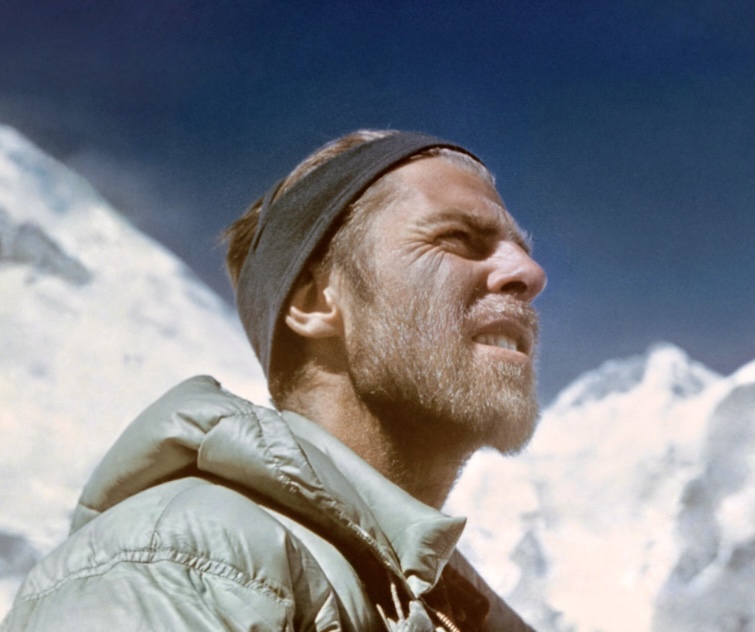

Nanga Parbat, 2005

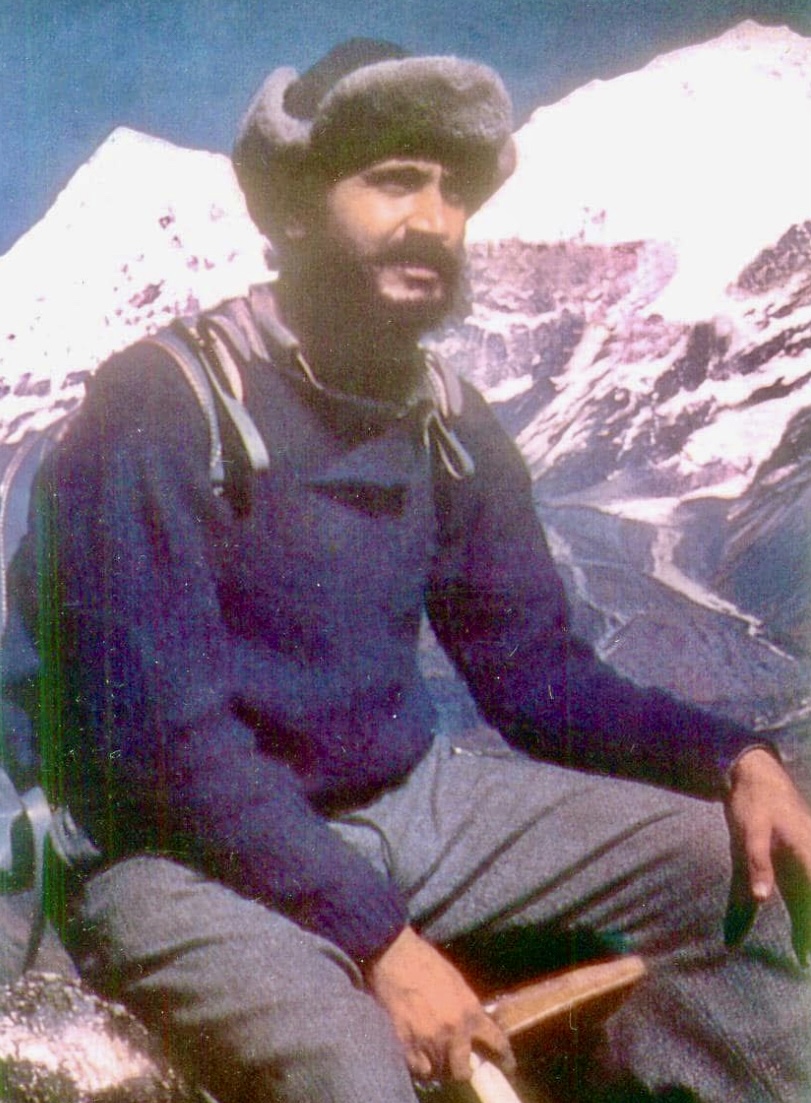

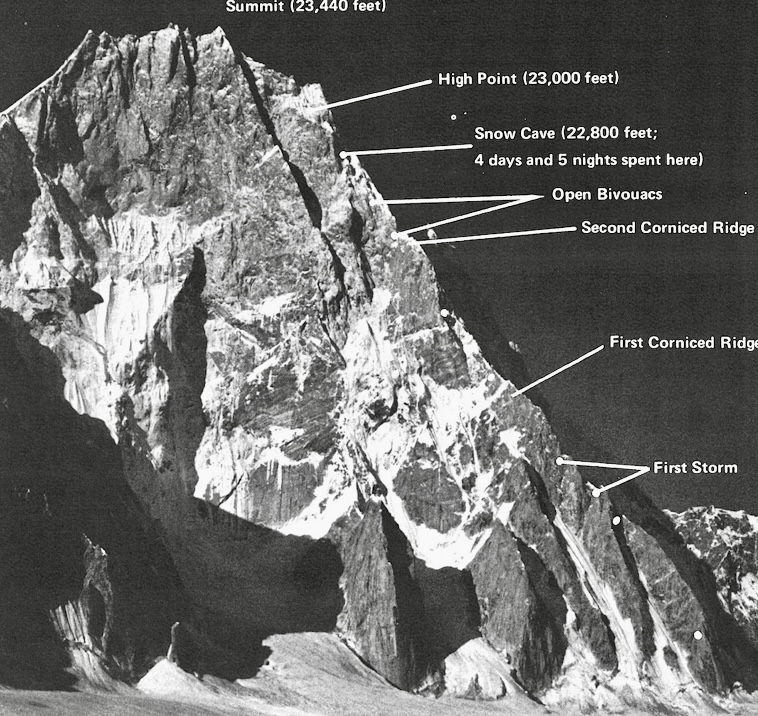

In 2005, Kim climbed Nanga Parbat’s massive Rupal Face. The Korean Nanga Parbat Rupal Expedition lasted 109 days. They arrived at Base Camp on April 20 after a heavy snowstorm. Over the next 12 days, the team set up Camp 1 at 5,280m and Camp 2 at 6,090m, following a line close to the 1970 Messner Route.

The weather was brutal, with snow falling daily in May, destroying seven tents and burying Camp 2 under fresh snow. Despite these setbacks, by June 14, after 43 days of effort, the team established Camp 3 at 6,850m. Near the end of June, the team prepared for a summit attempt, and on June 26, Kim and three other climbers started their push. However, at 7,550m on the Merkl Icefield, a rock hit team member Kim Mi-gon in the leg, forcing the group to abort.

Undeterred, Kim and climbing partner Lee Hyun-jo made another attempt on July 13, starting from Camp 4 at 7,125m. They faced constant danger, dodging falling rocks and ice. After a 24-hour climb, they reached the summit of Nanga Parbat.

Kim Chang-ho. Photo: Abbas Ali

A difficult descent

Kim and Lee chose to go down the Diamir Face via the Kinshofer Route, unroped, to save time. In the middle of the descent, they triggered a wind slab avalanche. Lee was buried, and Kim was swept 50m downhill, scraping his face and losing his headlamp. Both managed to free themselves and continued down, exhausted and hallucinating, believing another climber was ahead of them. They reached another expedition’s tents at 7,100m but decided against stopping, fearing they might not wake up if they rested. After an incredible 68 hours from Camp 4, they arrived at the Diamir Base Camp, impressing others with their speed and resilience. Lee appeared remarkably fresh despite the ordeal.

This expedition was a turning point for Kim. The climb was a tactical, siege-style effort, relying on fixed ropes and a larger team, very different from the lightweight, alpine-style climbs he later became known for. During the descent, Lee’s emotional radio call to a teammate at Base Camp, expressing regret that they weren’t together, deeply affected Kim.

Kim reflected on his selfishness, realizing that reaching the summit meant little without returning safely with his team. This experience shaped his philosophy moving forward, which would emphasize teamwork, respect for the mountains, and survival over personal glory.

Views of Everest from neighboring Lhotse. Photo: Kadyr Saydilkan

Everest, 2013: Starting from sea level

Kim’s 2013 Everest ascent was the final step in his quest to climb the 8,000m peaks without supplemental oxygen, making him the first Korean to do so. But his Everest climb was not just about reaching the top; it was a unique adventure.

Kim’s journey to Everest’s summit began far from the mountain itself. He wanted to make the climb special by starting at sea level and traveling to Base Camp without using motorized transport.

On March 20, 2013, he began his expedition from Sagar Island near Kolkata, India. From there, he kayaked 156km on the River Ganges, cycled 893km through northern India to Tumlingtar in Nepal, and then trekked 162km to Everest Base Camp. This sea-to-summit approach was rare and challenging, inspired by earlier climbers like Tim Macartney-Snape and Goran Kropp, but Kim added a twist by kayaking part of the way.

Once at Everest Base Camp, Kim prepared to climb the mountain via the standard Southeast Ridge route from the Nepal side without oxygen. He moved steadily up the mountain, navigating the Khumbu Icefall, the Western Cwm, and the steep slopes leading to the South Col. On May 20, Kim reached the summit.

Sadly, Kim’s climbing partner, Seo Sung-ho, died during the descent. This loss cast a shadow over the triumph, but Kim’s accomplishment remained a mountaineering landmark.

Kim Chang-ho and his team near the Sara Umga La at 5,020m, west of Dharamsura and Pasura peaks, in 2017. Photo: Korean Way Project

Mountaineering philosophy

Kim’s mountaineering philosophy viewed climbing as a means of learning and coexistence, not conquest. He avoided treating peaks as mere challenges, instead choosing routes with historical or cultural significance. After losing his partner Seo Sung-ho on Everest in 2013, Kim founded the Korean Himalayan Fund to support young climbers in creative ascents. His database, preserved by his wife Kim Youn-kyoung, includes detailed notes on geography and local names.

Kim’s death

Kim’s life ended on October 11, 2018, when an avalanche, possibly triggered by a serac collapse, destroyed his team’s Base Camp beneath 7,193m Gurja Himal, located south of Dhaulagiri VI, in Nepal. The Korean Way Project expedition, aiming for a new route on the south face, included five South Korean climbers and four Nepali guides, all of whom perished.

Kim’s journal, ending on October 10, suggests the tragedy struck overnight. By the time of his death, he was recognized as South Korea’s most accomplished climber. Kim was 49 years old.

His legacy endures through his database, the Korean Himalayan Fund, climbers like Oh Young-hoon who carry forward his vision, Kim’s daughter (Danah, born in 2016), his wife, and through the international mountaineering community, who preserve his memory.

Kim Chang-ho. Photo: En.namu.wiki

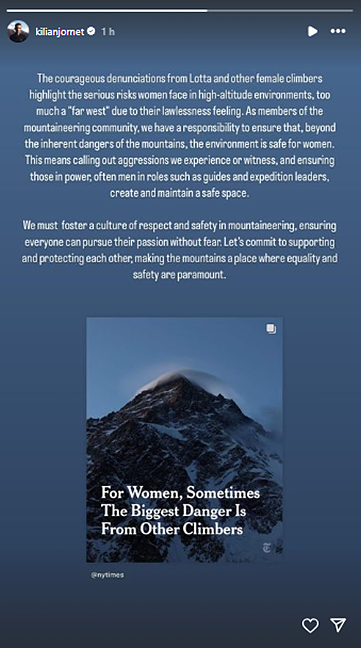

Naila Kiani is on her way to becoming the first Pakistani woman to complete the 14x8,000'ers, but her impact goes beyond summits. Kiani is driving change in her country's mountaineering scene, speaking up for those without a voice and making more than a few enemies along the way.

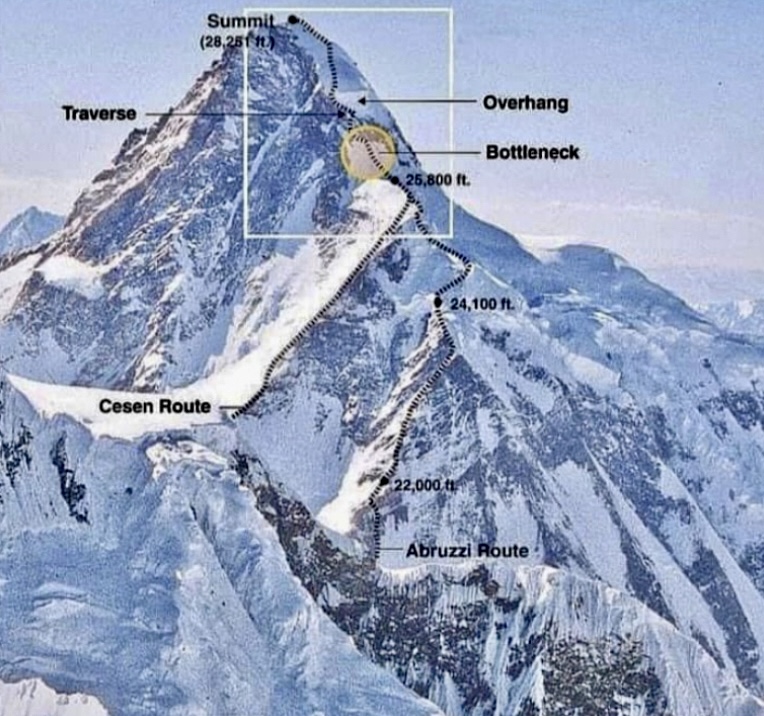

During her 14x8,000m quest, Kiani has been a reliable, outspoken witness in the usually secretive commercial climbing industry. She was the one who denounced how climber Ali Akbar Sakhi of Afghanistan was abandoned close to Camp 3 on K2, and faced threats when she accused Sakhi's outfitter of negligence.

Kiani also reported what happened on Shisha Pangma in 2023, when a race to become the first American woman to finish the 8,000m list ended with both women's deaths, alongside their Sherpas. After porter Ali Muhammad Hassan died at K2's Bottleneck, and a hundred climbers passed him on their way to the summit, Kiani coordinated a team of local climbers to return his body in the highest retrieval operation ever performed on K2. She has also led cleaning campaigns on the mountain.

This year, Kiani has spoken out on behalf of a group of local porters whose outfitter had not paid them. She knew the porters were too vulnerable to protest by themselves and that the loss of income might mean misery and hunger for their families.

Changes in aerial rescues

In the last few weeks, Kiani also made two promising announcements: the establishment of a mobile medical dispensary in the Karakoram and a change in helicopter protocols for mountain rescues in Pakistan. Until now, army pilots have managed helicopter rescues, flying in two helicopter patrols that charged $26,000 per flight -- the most expensive fee in the world.

"Last year, I spoke out against the extremely high prices that sick and injured climbers were being charged for helicopter evacuations," Kiani said. "Many told me to stay quiet, and that no one would listen."

Instead, she wrote letters and contacted high-ranking army officials directly. Kiani provided lists of prices comparing aerial rescue services and their costs in several mountain ranges around the world.

"I clearly explained that climbers evacuated in Pakistan were paying way, way too much," Kiani told ExplorersWeb.

To the surprise of the skeptics, the military listened. The new president of the Alpine Club of Pakistan (and Army General), Irfan Arshad, supported Kiani in this quest. The protocols have now changed, and, if applied, the impact will be huge.

Rescues 60% cheaper

Now, the helicopters don't need to fly in pairs.

"Only one helicopter is being sent for rescues, bringing the cost down to under $9,900 on average, nearly one-third of what climbers were paying before," Naila explained.

The change will also double the rescue capacity of the Pakistani air force, as each helicopter may attend to a different rescue at the same time.

Kiani has also insisted on a stricter account of the rescue charges, as the previous cost (calculated per hour of flight time) was sometimes inaccurate.

Finally, Kiani hopes the new protocols will prioritize serious medical cases without insurance companies agreeing to foot the bill first. This would greatly benefit many local porters, who either lack insurance or have limited coverage.

Kiani is hopeful costs will decrease immediately, but she also foresees further improvements. She told Explorersweb that the situation will improve when Pakistan allows private helicopter companies to operate rescues (as they can in Nepal), which Kiani is confident will happen in the future. In her opinion, private companies will lower costs and may be more flexible regarding altitude and weather conditions for rescues.

These improvements may seem logical, but in a country like Pakistan, where the army is incredibly powerful and rarely influenced by external forces, what Kiani has achieved is more extraordinary than any of her climbs.

Dispensaries in the Karakoram

Kiani has also lobbied for (and helped finance) the installation of two paramedical dispensaries along the Baltoro during the summer season. One is already operating at Concordia, one day from K2 Base Camp, and another is ready to start operating in Urdukas, as soon as the assigned nurse gets there.

"They will treat everybody for free: trekkers, climbers, and locals working in the area," Kiani said. "Finally, there is a semi-permanent facility to provide sanitary care during the Baltoro trek: igloos prepared to endure harsh weather."

The lack of facilities was a serious problem, particularly for local porters who had nothing to treat their injuries and disinfect wounds. With no help, even small health issues rapidly developed into serious medical conditions.

"We don't have a doctor yet, but the nurse managing each dispensary can treat a wide range of issues," Kiani said.

Kiani will pay the nurse's salary while Pakistan's Alpine Club will cover the rest.

Not just words, actions

These changes come after years of very little progress to improve the welfare of climbers and, most of all, local communities working in the climbing industry.

"I am not the only one who speaks up," Kiani said. "Other climbers also make their voices heard, but it is one thing to speak about something we think is wrong, and another to take action to change it. I strongly believe that if you want things to change, you need to take action."

Kiani's campaign for change has made enemies, but it has also received important support, such as from the Alpine Club of Pakistan and Green Tourism, a private institution that works closely with the country's government. "Without their help, I couldn’t have achieved what I did this year," Kiani explained.

Yet speaking up takes a toll, especially in the close-knit Pakistani climbing community. When Kiani pointed a finger at the negligence of some local operators, she faced harsh criticism and accusations of jealousy or courting controversy.

But Kiani insists that these negative aspects impact the entire Pakistani tourism industry.

"I can't help thinking that Pakistan has such huge potential for mountain tourism, and that mountain tourism can make a life-changing impact on local communities."

In addition to her determination, Kiani has something else in her favor: She is well-educated, with experience making a case, with plenty of proof and documentation, to draw the attention of senior officials. She is a Dubai-based engineer who has worked as a banker, although she quit her full-time job to pursue climbing in 2023.

Breaking social boundaries through climbing

Kiani summited Kangchenjunga, her 12th 8,000'er, last spring. While she has not confirmed her plans for fall, she intends to climb Shisha Pangma and Dhaulagiri to complete the 14x8,000m challenge.

"I get some criticism because I use oxygen and Sherpa support, but climbing has given me a voice and I’m using that voice to try to make a difference," Kiani told ExplorersWeb.

Kiani has become an influential figure for young Pakistani women.

"Gender equality is a real issue. Women here sometimes don’t have confidence and self-belief, so I wanted to inspire Pakistani women," she explained. "If I can do things that are not associated with Pakistani women, and if I can speak up about things that others won’t even dare, then hopefully others can do the same."

Pakistan ranked last (148th out of 148 countries) in the World Economic Forum's Global Gender Gap Index in 2025, with a score of 56.7%. Dawn.com cited data from the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan (HRCP) showing that in 2024, "honor" killings continued to be a serious issue across Pakistan. That year, 346 people (nearly all women) were victims of these so-called honor crimes.

Around 3:30 pm on July 2, an SOS signal from a Garmin InReach device reached the California Governor’s Office of Emergency Services. It had been sent from just below the summit of 4,383m Mt. Williamson, the second-highest peak in the Sierra Nevada.

The sender, whose name authorities have not released, had fallen and sustained serious injuries. She also lost most of her equipment. Her situation soon became even more desperate when a thunderstorm rolled in. Lightning menaced her, and lashing rain beat over the area as a multi-agency rescue operation launched. But the weather, her severe injuries, and the difficult location kept her stranded for many hours.

The woman had been scrambling off-route near the West Chute on Mt. Williamson. While snow-free in July, the nearly 500m chute has sections of loose scree which make it difficult. Mt. Williamson is trickier to summit than the slightly taller Mt Whitney. There is no established trail above 3,000m, and there aren't many fellow climbers around.

The woman was just a few hundred meters from the summit when she fell, losing her backpack and badly breaking her leg. Over her Garmin, she described the grisly compound fracture -- a fracture where the bone protrudes through the skin -- and her lack of food, water, and extra clothing.

A series of helicopter attempts

California Highway Patrol sent an Airbus H125 helicopter to pick up rescue volunteers. By the time rescuers were on board, the storm had fully descended, bringing cloud cover that prevented the helicopter from reaching her.

More resources were called in, and the nearby China Lake Naval Air Weapons Station agreed to lend aid. They transported search-and-rescue workers to Shepherd's Pass, around 3,000m up, but couldn't get any closer. This was around midnight. Volunteers proceeded on foot, reaching the bottom of the west face by sunrise.

They were able to call up to the stranded climber, but the terrain prevented them from reaching her. By then, however, the weather had improved somewhat, and the helicopter returned and dropped two rescuers about 100m above her. They carefully made their way down, reaching her 23 hours after her fall.

They still had to get her out. Again, SAR personnel called in more resources. The Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department's Air 5 helicopter buzzed over, but the elevation proved too much. Finally, the California National Guard offered their Blackhawk Spartan 164.

SAR workers on the ground carefully moved her into a more open position. Just after 7 pm on July 3, 28 hours after her fall, she was hoisted aboard Spartan 164 and eventually transferred to a hospital.

According to a statement from Inyo County Search and Rescue, the victim displayed "Enormous bravery and fortitude...and all involved were impressed by her ability to remain calm, collected, and alive."

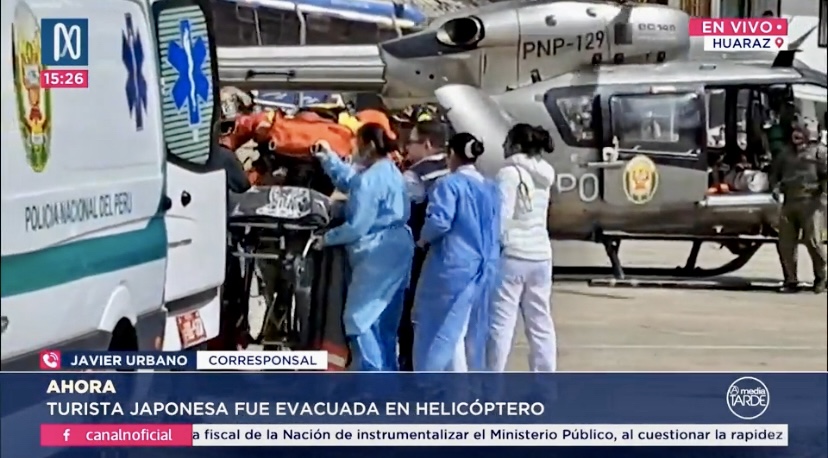

Experienced climbers Saki Terada and Chiaki Inada from Japan faced severe challenges while climbing 6,757m Nevado Huascaran earlier this week. Their climb of Peru's highest peak ended in tragedy.

The duo became stuck at 6,600m during their descent. Inada died, and rescue teams struggled to help Terada down.

Yesterday, rescuers finally evacuated Terada from the mountain, transporting her to Víctor Ramos Guardia Hospital in Huaraz. She is in a critical but stable condition, suffering from severe dehydration and frostbite on her hands and feet from prolonged exposure to extreme cold, according to Infobae.

Today, medics will transfer her to a hospital in Lima, Peru's capital city, where she can continue treatment.

Inada's body recovery underway

Efforts are underway to recover Inada's body. Inada, a 40-year-old doctor for Wilderness Medical Associates Japan (WMA), succumbed to hypothermia and cerebral edema.

According to some Peruvian sources, rescue services found the climbers at approximately 6,500m on the south face of Huascaran’s south peak, just below the summit. They were on the technical Escudo route, a 600m ice and snow wall known for its steep terrain and harsh weather.

Terada and Inada had arrived in Peru two weeks ago and had at least one acclimatization hike before starting the ascent on Huascaran. Presumably, the two women summited on June 23, and the problems started on June 24 when they encountered foggy weather and low visibility.

Timeline of events

Today, WMA Japan has published a report on what happened. Below we have translated it into English with minor edits to improve clarity. Note all times referred to are Peru Standard Time.

June 24

At around 1:30 am:

- Chiaki Inada became incapacitated due to suspected hypothermia. A distress signal was sent via Garmin’s SOS satellite device to a private rescue agency in Peru. The agency contacted WMA Japan to verify the situation.

At around 4:00 am:

- A response headquarters was established, and negotiations began with various parties.

- Requests for rescue to the local private rescue agency and to local police authorities.

- Request for support through the Japanese Embassy in Peru.

At around 7:30 am:

- Online meeting with Japanese and Peruvian stakeholders.

- Survival of Inada and Terada confirmed.

- Text communication with Japan was possible until around 10:00 am. The climbers were stranded and incapacitated at the site.

- Rescue arrangements confirmed.

- The climbers' problems occurred around 6,600m, just below the summit. No helicopters in Peru can fly at this altitude, so the rescue team had to fly to the Huascaran refuge hut, then proceed on foot to the site. The plan was to bring both climbers to the refuge hut by land, followed by a helicopter rescue.

- Cooperation from local police was secured through the Japanese Embassy in Peru.

At around 4:00 pm:

- A joint rescue operation by local police and private teams began. Nine team members, split into three groups, arrived at the Huascaran refuge hut.

- The team began climbing toward the stranded climbers on foot.

- Additional teams were dispatched through efforts by the Japanese Embassy and local stakeholders.

- The rescue team consisted of over 10 members, primarily local mountain guides, operating in several groups.

June 25

At around 7:30 am:

- Staff at a lodge at the mountain’s base reported phone contact with Inada and Terada

- Though their responses were not entirely clear, their voices were confirmed.

At around 12:00 pm:

The rescue team approached the SOS location but encountered difficulties due to large crevasses. They continued searching for a viable route.

At around 3:00 pm:

- The rescue team reached the two stranded climbers. Terada was conscious. Inada was unconscious and in critical condition.

- The team provided first aid and considered transport options through the night.

At around 6:00 pm:

- Deteriorating weather conditions made rescue operations extremely difficult, rendering simultaneous transport of both climbers impossible.

- Local rescue teams and authorities determined Inada’s death at the site.

- Further rescue activities became unsafe, so Inada’s body was temporarily left at the site with its location recorded via GPS.

- The rescue team focused on evacuating Terada.

June 26

At around 9:00 am:

- Terada was walking at approximately 5,100m (the pickup point is at about 4,500m).

- A helicopter and local medical personnel were on standby for transport.

- The plan was to transport Terada to a hospital at the base via helicopter upon reaching the pickup point.

At around 1:45 pm:

- Terada safely reached the helicopter pickup point at the refuge hut.

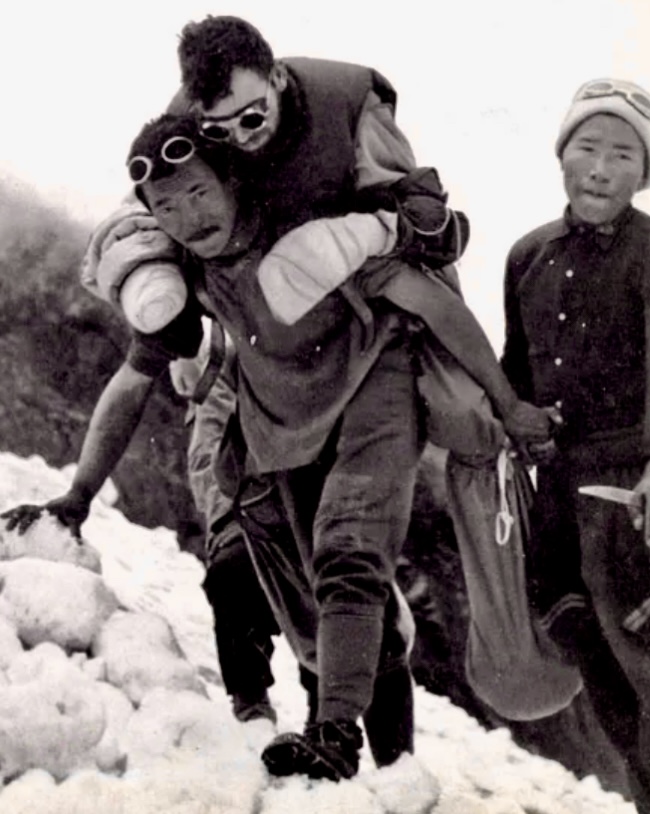

- Partway down, she became unable to walk independently and was carried by the rescue team, but remained fully conscious.

- Final landing arrangements and flight permissions were being coordinated, with the helicopter set to deploy once conditions were met.

At around 2:30 pm:

- Thanks to the rescue team’s swift coordination, Terada was safely admitted to a hospital.

- Preparations for the recovery of Inada’s body have begun.

At around 10:00 pm:

- A team of local mountain police and guides left to retrieve Inada’s body.

Captain Manmohan Singh Kohli, a pioneering Indian mountaineer, passed away on June 23 at the age of 93.

Celebrated for leading India’s first successful Everest expedition in 1965, Captain M.S. Kohli's career also included an Antarctic expedition and many other Himalayan ventures. His work as a mountaineer, author, editor, Himalayan Club president, and Indian Mountaineering Foundation president shaped Indian mountaineering.

Born December 11, 1930, in Haripur (now Pakistan), Kohli joined the Indian Navy in 1950, rising to the rank of Commander. He trained in the UK and developed leadership skills. By 1956, he began Himalayan mountaineering.

Kohli took part in over 20 adventures in the Greater Ranges. In 1956, he climbed 7,672m Saser Kangri in the Karakoram. In 1959, with K.P. Sharma, he topped out on 6,861m Nanda Kot in the Kumaon Himalaya. It was just the second ascent of the mountain.

Between 1961 and 1964, Kohli led three successful expeditions -- the first ascent of Annapurna III, a climb of 7,816m Nanda Devi, and an expedition to 7,198m Nepal Peak.

In the 1960s, Kohli led and summited Kabru Dome and Rathong, strengthening India’s eastern Himalayan presence. In 1965, Kohli led a covert Indian-American mission to place a nuclear-powered device to monitor Chinese tests but did not summit due to harsh conditions.

Everest expedition leader

In 1965, Kohli led the first successful Indian expedition to Everest. Nine climbers on his team summited between May 20–29. It set a record for the most summiters on one expedition, which remained unbroken for 17 years.

His leadership on that expedition was extraordinary. Indira Gandhi, who later became the Prime Minister of India, said of Kohli at the time: "Commander Kohli’s expedition...was a masterpiece of planning, organization, teamwork, individual effort, and leadership.”

Later, Kohli climbed several European peaks with Tenzing Norgay. In 1982–1983, he led India’s first civilian Antarctic expedition, supporting scientific exploration.

He was also a committed alpinist beyond expeditions. As president and vice president of the Himalayan Club (1980–1983), Kohli edited the Himalayan Journal. As president of the Indian Mountaineering Foundation (1989–1993), he promoted adventure and youth engagement. In 1989, he co-founded the Himalayan Environment Trust with Sir Edmund Hillary. It was supported by Maurice Herzog, Reinhold Messner, Junko Tabei, and Chris Bonington.

Kohli was much loved and respected in international mountaineering circles. He promoted mountaineering and trekking through many presentations around the world.

Kohli authored Nine Atop Everest, Spies in the Himalayas (with Kenneth Conboy), The Great Himalayan Climb, and A Life Full of Adventures, among several other publications.

Kohli received the Padma Bhushan (1965), Arjuna Award (1965), Ati Vishisht Seva Medal (AVSM), and Tenzing Norgay Lifetime Achievement Award. He lectured at the Alpine Club (UK) and the American Alpine Club.

Captain Kohli’s passing marks the end of an era, but his expeditions, leadership, writings, and conservation efforts will continue to inspire.

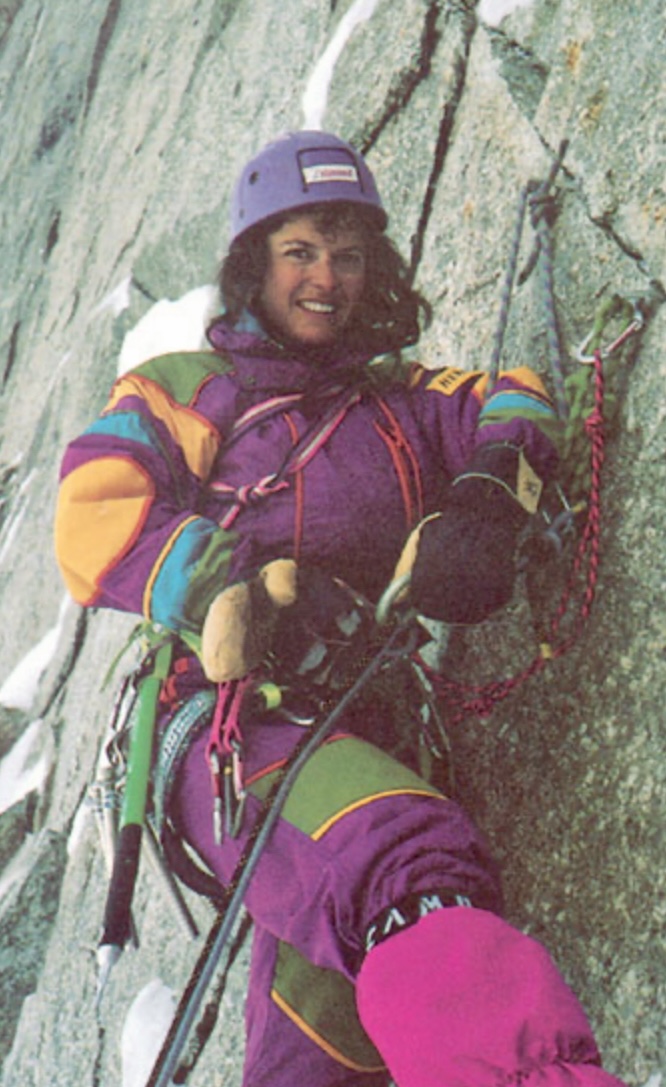

One of Poland's great alpinists of the 1970s and 80s, Krystyna Palmowska, died yesterday in a climbing fall in Slovakia’s High Tatras, according to Polish sources.

The accident occurred on June 15, and her body was found today, June 16, by the Slovak Mountain Rescue Service after ground and helicopter searches.

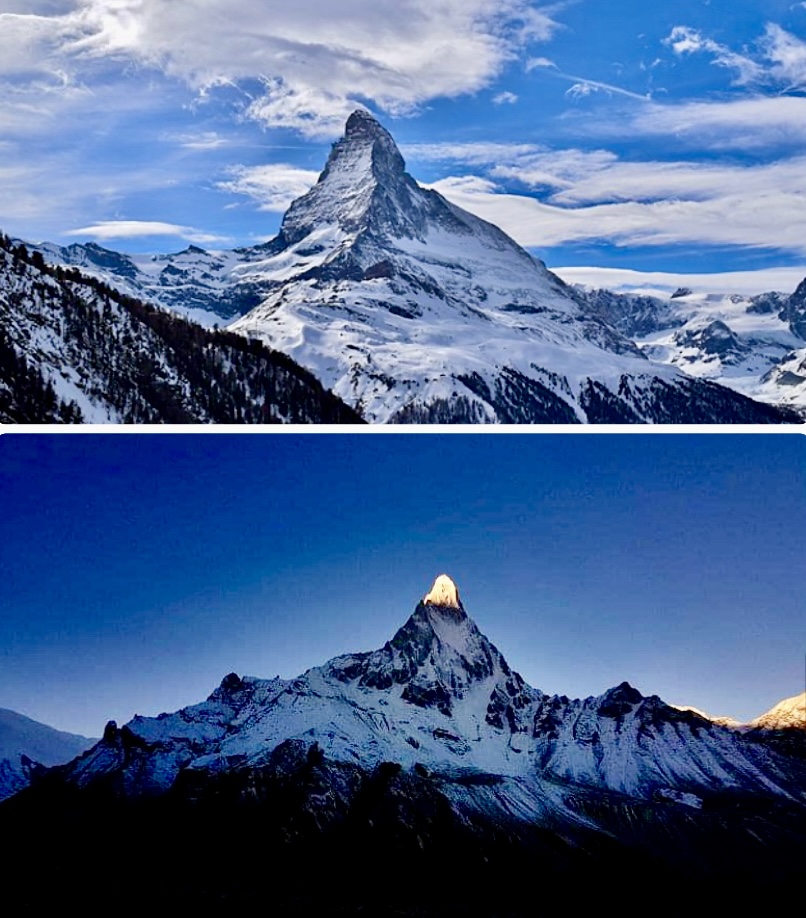

Palmowska, 76, was one of the best female alpinists of her generation -- a generation when the Poles, both men and women, dominated high-altitude mountaineering. Her remarkable climbs included:

- 1977: Matterhorn North Face – 2nd all-female ascent

- 1978: Matterhorn North Face – 1st all-female winter climb

- 1979: Rakaposhi (7,788m) – New route

- 1982: Member of the K2 Women's Expedition

- 1983: Broad Peak (8,047m) – 1st woman summiter

- 1985: Nanga Parbat (8,126m) – 1st all-female ascent

- 1986: K2 Magic Line – Reached 8,200m with Anna Czerwinska

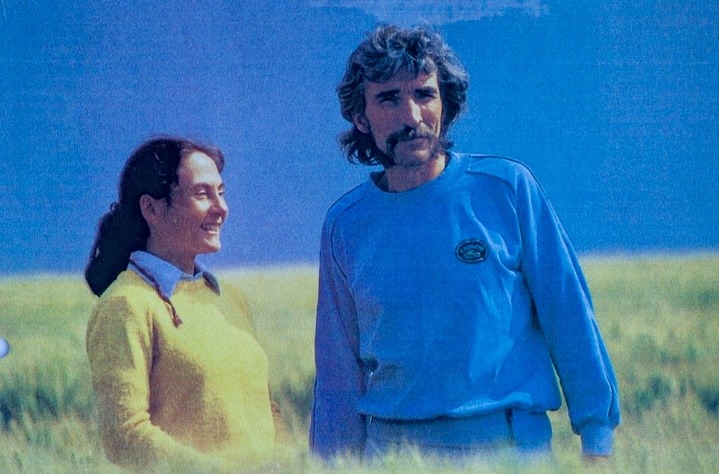

Today, 104 years ago, legendary French alpinist Gaston Rebuffat was born.

One of the most celebrated mountaineers of the 20th century, Rebuffat was known for his bold new routes in the Alps, his role in the first confirmed ascent of an 8,000m peak (Annapurna I in 1950), and as the first person to climb all six great North Faces of the Alps. He wrote several influential mountaineering books and produced films that captured the essence of alpinism.

Early climbs

Rebuffat was born on May 7, 1921, in Marseille, France. He started climbing at 14 in the Calanques, a rugged coastal area near his hometown. In 1937, at 16, he joined the French Alpine Club, where he met Lionel Terray, a future climbing partner. Rebuffat visited Chamonix for the first time in 1937, and the Alps soon became his focus.

During World War II, Rebuffat took his climbing to a new level. In 1942, he graduated from Jeunesse et Montagne, a French youth training program, and received his mountain guide certification (despite being two years younger than the minimum age requirement of 23). In 1944, Rebuffat became an instructor for the French National Ski and Mountaineering School (ENSA) and the High Mountain Military School.

By 1945, he was focused on guiding clients in the Alps, fulfilling his desire to live in the mountains full time. He joined the prestigious Compagnie des Guides de Chamonix.

Climbs in the Alps

Rebuffat’s climbing career in the Alps was outstanding, with over 1,200 ascents classified as difficult or very difficult. In the 1940s, Rebuffat tackled some of the Alps’ most challenging peaks, alongside partners such as Terray and Louis Lachenal. By the end of the 1940s, Rebuffat was among France’s elite mountaineers.

In the 1940s and 50s, Rebuffat established approximately 40 significant first ascents via new routes. These included routes on the Aiguille du Midi, the Drus, and Aiguille du Roc. His new lines were known for their elegance and technical challenge, and reflect his philosophy of climbing in harmony with the mountain rather than conquering it.

The six North Faces of the Alps

Rebuffat finished his most celebrated achievement in 1952. The North Faces of the Matterhorn, Eiger, Grandes Jorasses, Piz Badile, Drus, and Cima Grande di Lavaredo are well known for their steepness, difficulty, and unpredictable weather.

Rebuffat began to plan his first North Face, the Grandes Jorasses, in 1938, when he was only 17 years old. The first ascent -- by Italians Riccardo Cassin, Gino Esposito, and Ugo Tizzoni -- inspired him.

On Rebuffat's first attempt, in 1943, bad weather forced him to retreat. Finally, in July 1945, he succeeded, climbing the Walker Spur with Edouard Frendo in three days with two bivouacs. This marked the second ascent of this route.

In August 1946, Rebuffat guided Belgian amateur mountaineer Rene Mallieux up the North Face of the Petit Dru. They climbed fast to reach the summit by nightfall, bivouacking on the descent and attending the Chamonix Guides’ Festival the next day. The one-day ascent showcased Rebuffat’s efficiency and guiding skills.

In the summer of 1948, Rebuffat guided a client up the northeast face of Piz Badile in the Bregaglia Alps. Despite a severe lightning storm, they reached the summit the following day. They followed the Cassin Route, first ascended in 1937.

Rebuffat’s fourth North Face came in 1949 when he climbed the Matterhorn twice, first with Raymond Simond, and later with other partners (though some sources mention only one ascent). He targeted the Schmid Route, first climbed in 1931.

The same year, Rebuffat ascended the North Face of Cima Grande di Lavaredo in the Dolomites, guided by Italian Gino Solda. This ascent followed the Comici-Dimai Route, first climbed in 1933.

In July 1952, Rebuffat completed his quest with the North Face of the Eiger via the Heckmair Route. He climbed with Paul Habran, Guido Magnone, Pierre Leroux, and Jean Brune.

Annapurna I

In 1950, Rebuffat joined a French expedition to Annapurna I. Led by Maurice Herzog, the team included Rebuffat, Terray, and Lachenal, among others. The expedition started in March, but the ascent only began in May.

The French party established a base camp and four intermediate camps, the highest at 7,400m. On June 3, Herzog and Lachenal summited and became the first two people in the world to reach the top of an 8,000m peak. Rebuffat and Terray didn’t summit, but played a critical role during the descent.

While summiting was a historic triumph, the descent turned into an ordeal, marked by frostbite, snowblindness, avalanches, and navigational errors. Rebuffat helped to ensure the survival of frostbitten and disoriented teammates during the harrowing retreat.

Herzog and Lachenal reached the top around 2 pm and started to descend immediately. The weather was clear but very cold, with temperatures estimated at -40°. Herzog somehow lost his gloves while handling equipment, exposing his hands. Lachenal, impatient to descend quickly in the worsening conditions and with his own frostbite concerns, slipped and tumbled 100m down the slope. Miraculously, he stopped short of a fatal drop, but the accident left him shaken, with one crampon missing, and his ice axe gone. His feet, already numb from prolonged exposure, were deteriorating rapidly. Both men were in a very bad state as they struggled toward Camp 5 at 7,440m, where Rebuffat and Terray awaited.

Meeting Rebuffat and Terray

Rebuffat and Terray had climbed to Camp 5 earlier that day, expecting to support Herzog and Lachenal or possibly attempt the summit themselves if conditions allowed.

When Herzog arrived at the high camp alone, Rebuffat and Terray were relieved, but then alarmed when they shook his hand. Herzog’s hands were frozen solid, white, and lifeless.

Rebuffat and Terray started to massage Herzog’s frostbitten hands and feet, hoping to restore the circulation, but their efforts had little result. Hearing some cries from below, Terray ventured out of the tent into the dusk and located Lachenal, who had missed the camp and was 200m down the slope. Terray guided Lachenal back to Camp 5. Lachenal’s feet were frozen, and he was disoriented from his fall and the altitude.

Rebuffat and Terray worked through the night to keep Herzog and Lachenal warm, using their body heat. Herzog’s hands and feet were turning black, and Lachenal’s toes were stiffening. Aware that the team needed to descend urgently for medical attention, Rebuffat helped organize the group for the next day’s descent.

Descending in cruel conditions

On June 4, in worsening weather, the four climbers set out to descend to Camp 4 at 7,150m. It was a whiteout, with heavy snow and almost zero visibility. Rebuffat and Terray had removed their glacier goggles the previous day while searching for the route, and both were snowblind.

The situation was critical. Two blind men were guiding two weak, injured climbers. Rebuffat relied on his instincts and memory of the route to help navigate, but the party struggled to locate Camp 4, missing it in the fog and snow. Exhausted, the four climbers had to bivouac in a crevasse for the night.

At dawn, on June 5, an avalanche poured into the crevasse, burying their boots and equipment. Rebuffat and Terray, still snowblind, dug frantically to recover their gear. Rebuffat was determined to keep the group moving.

Later that morning, teammate Marcel Schatz ascended from Camp 4 to search for them. Thankfully, he spotted the group and guided them to safety.

Rebuffat’s resilience

At Camp 4, Rebuffat was suffering early frostbite and snow blindness but coordinated the Sherpas' evacuation of his companions.

On June 5, during their descent to Camp 2, Rebuffat helped rescue Herzog and two Sherpas from an avalanche. By the afternoon, the team reached Camp 2. Finally, everyone reached base camp alive, though Herzog and Lachenal lost some digits.

Rebuffat died from cancer on May 31, 1985, in Bobigny, France at age 64. Rebuffat’s tombstone in Chamonix’s old cemetery bears a quote from his book Les Horizons Gagnes:

"The mountaineer is a man who leads his body to where, one day, his eyes have looked."

Legacy

Rebuffat wrote over 20 books on mountaineering, including Starlight and Storm: The Ascent of the Six Great North Faces of the Alps, Mont Blanc to Everest, On Ice and Snow and Rock, The Mont Blanc Massif: The 100 Finest Routes, Men and the Matterhorn, and Between Heaven and Earth. He also edited a mountaineering column for Le Monde.

Rebuffat also produced numerous films, including: Flammes des Pierres, Etoiles et Tempetes (which won the Grand Prize at the Trento Film Festival), Entre Terre et Ciel, and Les Horizons Gagnes.

Rebuffat’s commitment to share the beauty of the mountains continues to resonate with climbers and adventurers. His routes in the Mont Blanc massif are still climbed, and his books remain classics.

You can watch the film Etoiles et Tempetes (in French) below:

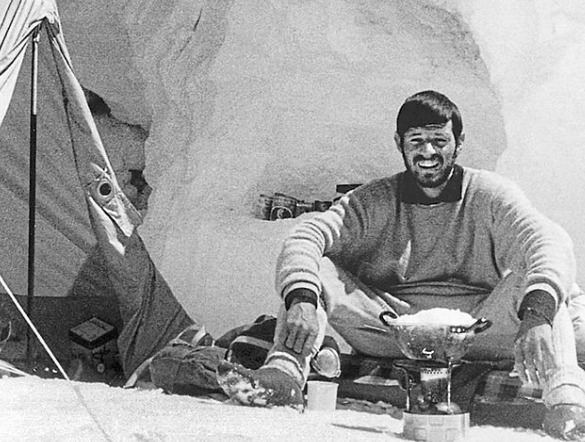

Lenin Peak, a towering giant in the Pamirs, has attracted climbers for decades. We examine its first ascents (one from the south and one from the north) as well as two expeditions that ended in tragedy, including the deadliest-ever mountaineering disaster.

Lenin Peak

Lenin Peak (7,134m) is located on the border between Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan in the Pamir Mountains. Its northern slopes are in Kyrgyzstan’s Alai Province, and its southern slopes are in Tajikistan’s Gorno-Badakhshan region. The summit lies on the border, making it a shared peak between the two countries.

It is the highest peak in the Trans-Alay Range, and the second highest in both Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, surpassed only by 7,495m Ismoil Somoni Peak in Tajikistan and 7,439m Jengish Chokusu in Kyrgyzstan.

Lenin Peak is one of five 7,000m peaks in the former USSR. Climbers must summit all five to achieve the prestigious Snow Leopard Award. Decades after the fall of the Soviet Union, climbers still pursue the Snow Leopard challenge.

A peak with many names

In 1871, the peak was named Mount Kaufman after Konstantin Kaufman, the first Governor-General of Russian Turkestan. In 1928, it was unsurprisingly renamed Lenin Peak.

The current official name differs between Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan. In Kyrgyzstan, it is called Lenin Chokusu (Lenin Peak), while in Tajikistan, it is Qullai Abuali Ibni Sino (Ibn Sina Peak or Avicenna Peak). Tajikistan renamed the mountain in 2006 after the Persian scholar Abu Ali ibn Sina.

Local Kyrgyz names include Jel-Aidar (Wind’s God) and Achyk-Tash (Open Rock).

We’ll call the mountain Lenin Peak, as it bore this name for three of the four expeditions we cover in this article.

Renowned as one of the most accessible 7,000’ers, hundreds of climbers visit Lenin Peak annually. Most climb the classic north face route, approaching from Osh in Kyrgyzstan. However, the mountain’s reputation as the easiest 7,000m peak is misleading because of its high altitude, unpredictable weather, and avalanche risk.

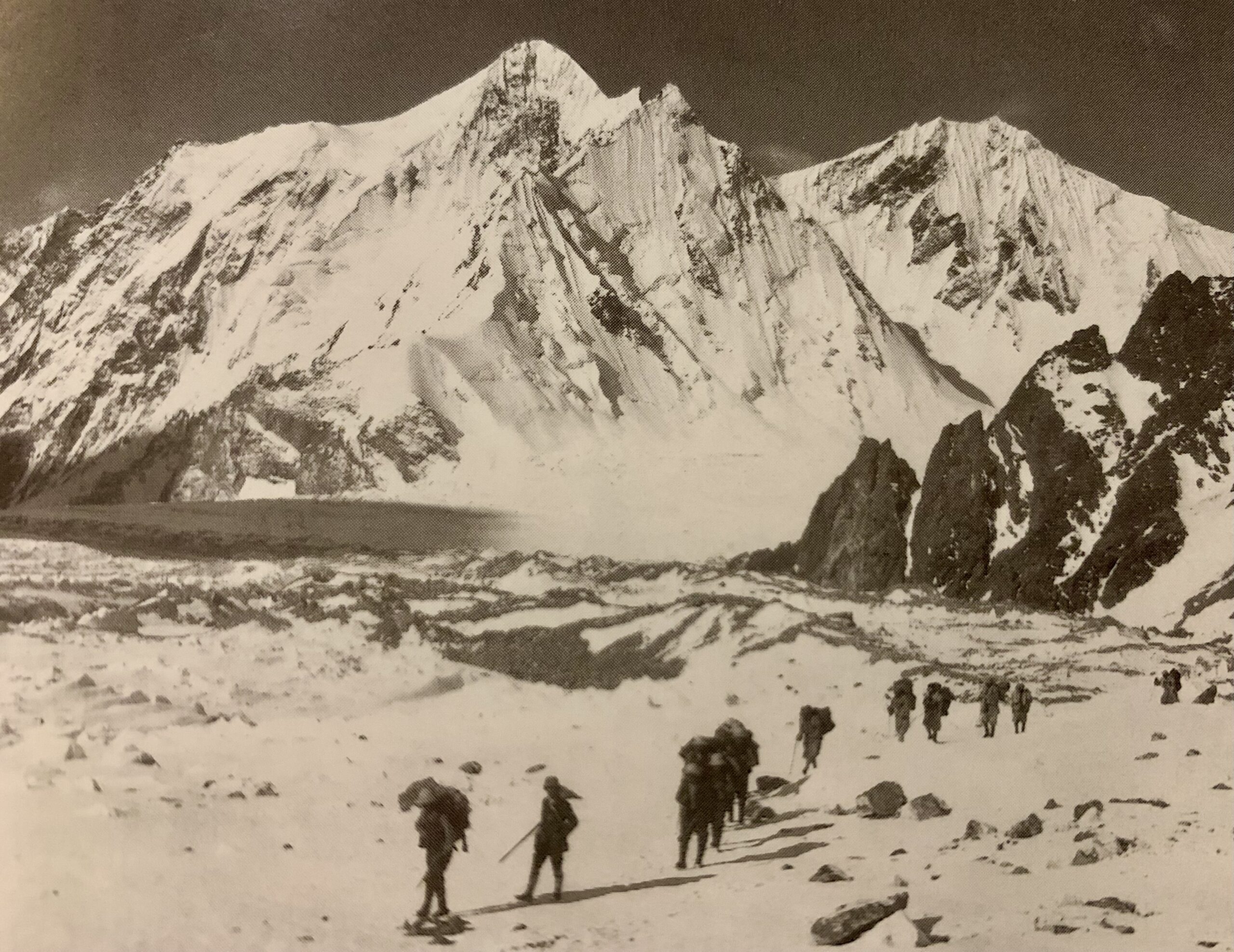

The first ascent

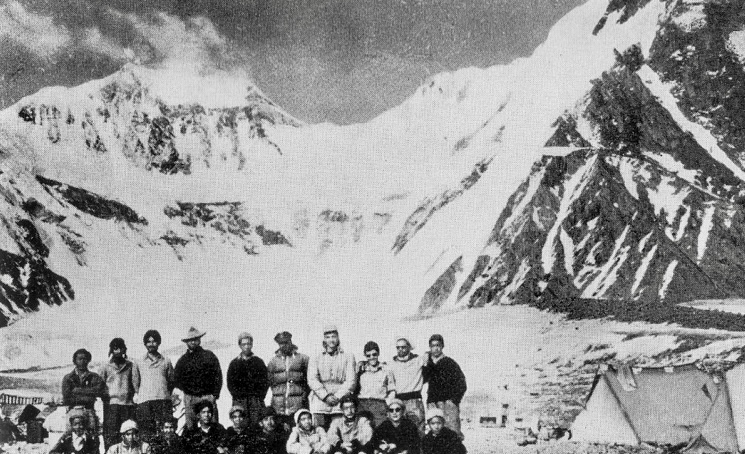

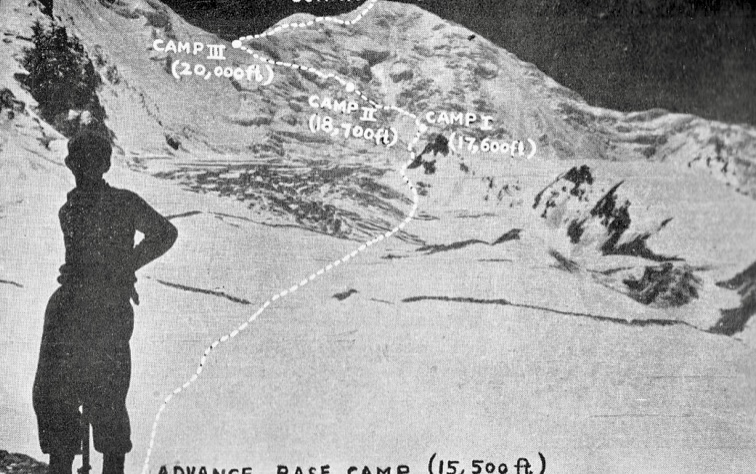

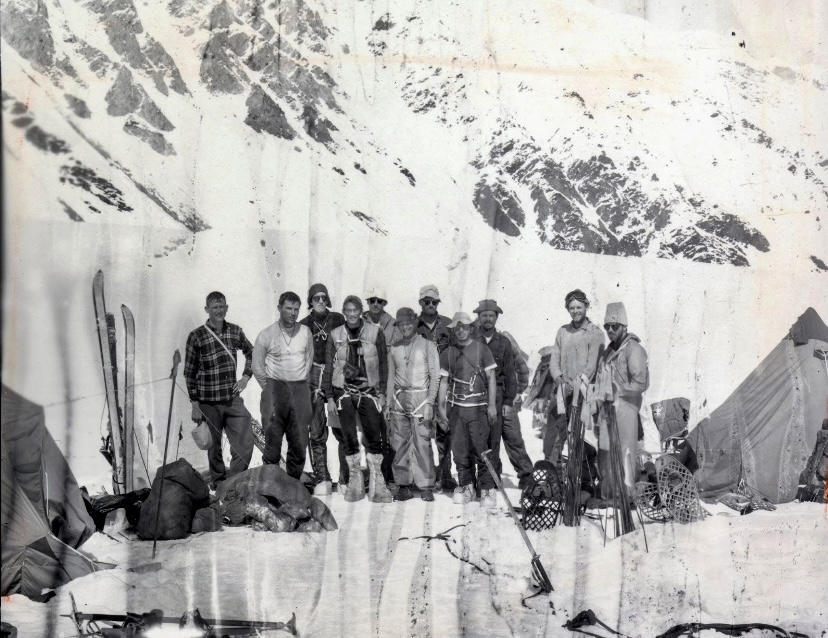

In September 1928, a Soviet-German expedition targeted Lenin Peak. The team included German climbers Eugen Allwein and Karl Wien, and Austrian Erwin Schneider, supported by Soviet climbers and porters. The expedition was a joint effort to map the Pamirs.

They approached from the south side, starting in the Saukdara River Valley, continuing up the south slope of the Trans-Alay Range, and then ascending via the Greater Saukdara Glacier. Their route wound from Krylenko Pass (a saddle that connects the Greater Saukdara Glacier to the upper slopes of Lenin Peak at 5,820m) to the northeast ridge toward the summit.

The three climbers faced brutal conditions with rudimentary gear: canvas jackets, wool layers, and leather boots with nail soles. High winds and subzero temperatures tested their endurance. On September 25 at 3:30 pm, Allwein, Wien, and Schneider reached the summit.

During the descent, the climbers suffered severe frostbite that required medical care in Osh. They left no summit proof on top, leading some to question their success. Despite some skepticism, authorities accepted their ascent, marking a historic first. The team also set a new mountaineering altitude record, surpassing that set by Alexander Kellas on 7,128m Pauhunri in 1911.

The first ascent from the north

In 1934, Soviet climbers tried from the northern side. The expedition, backed by the Red Army, included siblings Vitaly and Yevgeny Abalakov, Kasian Chernuha, and Ivan Lukin.

They started from Achik-Tash Canyon, ascending to Lenin Glacier’s western ice slope on the north face. They reached the crest of the northeast ridge at approximately 6,500m and continued along the ridge to the summit. En route, they established camps at 5,700m, 6,500m, and 7,000m.

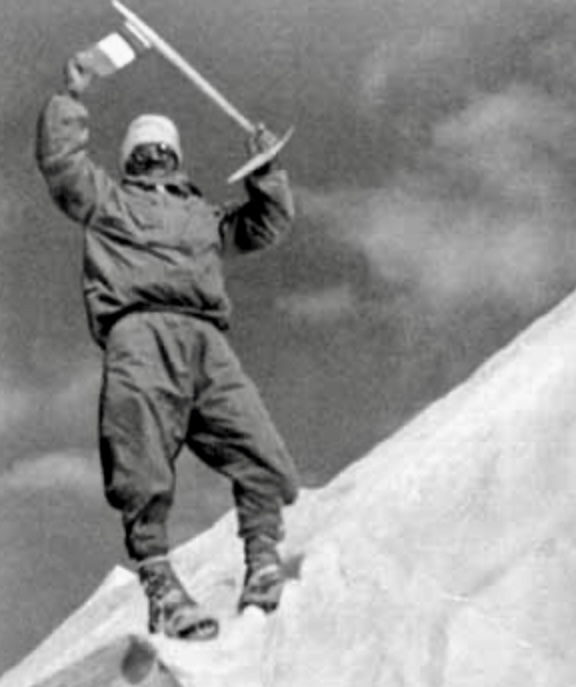

On September 8 at 4:20 pm, Chernuha, Vitaly Abalakov, and Lukin summited after a four-day climb. Abalakov placed a bust of Vladimir Lenin on the summit.

The 1974 tragedy

In 1974, Lenin Peak hosted an international mountaineering camp, attracting nearly 200 climbers.

A Soviet all-female team led by Elvira Shatayeva planned a traverse, ascending via the Lipkin Ridge on the north face, and descending the Razdelnaya Route on Lenin Peak's northern side.

The women topped out on August 7, despite warnings from base camp of an approaching storm. The storm, the worst in 25 years, caught them below the summit. The wind exceeded 100kph, shredded the party’s thin cotton tents, and exposed Shatayeva's team to temperatures below -20C°. They didn't want to abandon each other, and all eight stayed together until their last breath.

Shatayeva maintained radio contact with base camp, reporting dwindling supplies and frostbite. American climber John Roskelley and some nearby Japanese alpinists attempted a rescue but were repelled by the blizzard. Over two days, the women succumbed to hypothermia and exhaustion.

Shatayeva’s last radio message was: "I'm alone now, with just a few minutes left to live. See you in eternity."

All eight women perished, and climbers later found their bodies scattered along the summit ridge. The disaster, caused by inadequate gear and the ferocity of the storm, shocked the mountaineering community.

The deadliest mountaineering tragedy

In the summer of 1990, 45 climbers, primarily from the Leningrad Mountaineering Club, were at Camp 2 (5,300m) on what is now called the Razdelnaya Route on Peak Lenin's north face. The party included Soviet climbers Leonid Troshchinenko, Vladimir Voronin, and Alexei Koren (among others), six mountaineers from the former Czechoslovakia (including Miroslav Brozman), four Israelis, two Swiss climbers, and one Spaniard.

On July 13 at 9:30 pm, a 6.4-magnitude earthquake (with its epicenter in Afghanistan’s Hindu Kush) shook the Pamirs. It dislodged a serac from nearby Chapaev Peak, triggering a massive avalanche. Snow and ice hit Camp 2 on Lenin Peak, burying the climbers in seconds, and killing 43 people from five nations.

Koren and Brozman, who were positioned at the camp’s edge, survived with a broken arm and leg, respectively. They heard the trapped climbers’ cries as the debris froze into the glacial ice.

According to Charles Huss's report for the American Alpine Journal, a few other climbers were lucky to survive. Vladimir Balyberdin had decided at the last minute to move to Camp 3 with some friends, and six English climbers escaped because they had established their bivouac some distance from the main camp.

Rescue efforts

Soviet helicopters searched for the avalanche victims but initially could only recover one body. In 2004, because of glacial melt, human remains surfaced at 4,200m, with more emerging in 2008.

A plaque near the Achik-Tash base camp commemorates the victims of the 1990 disaster. It remains the deadliest single mountaineering accident in history.

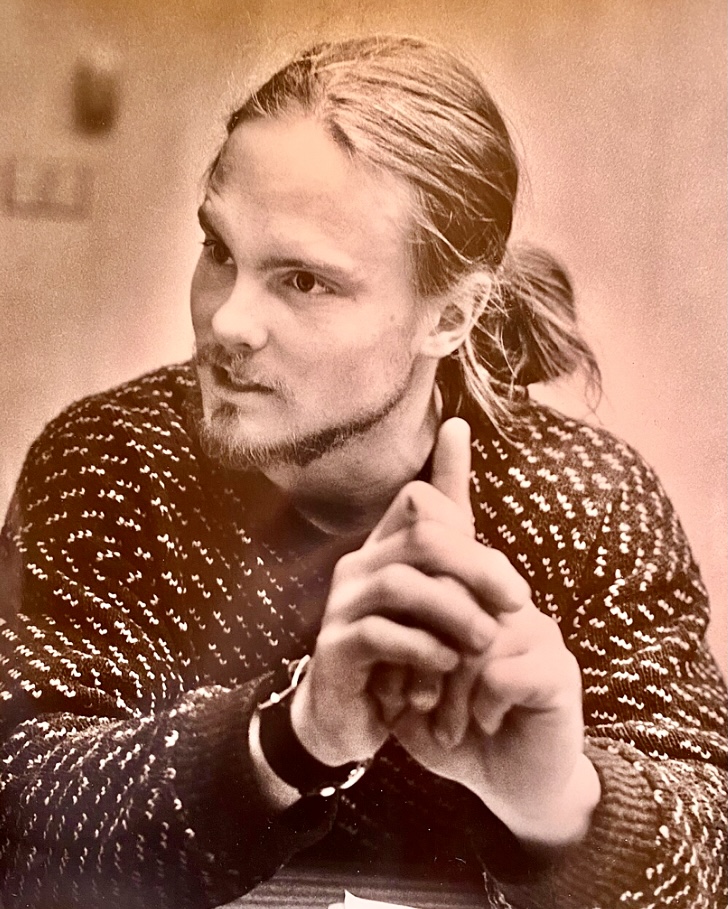

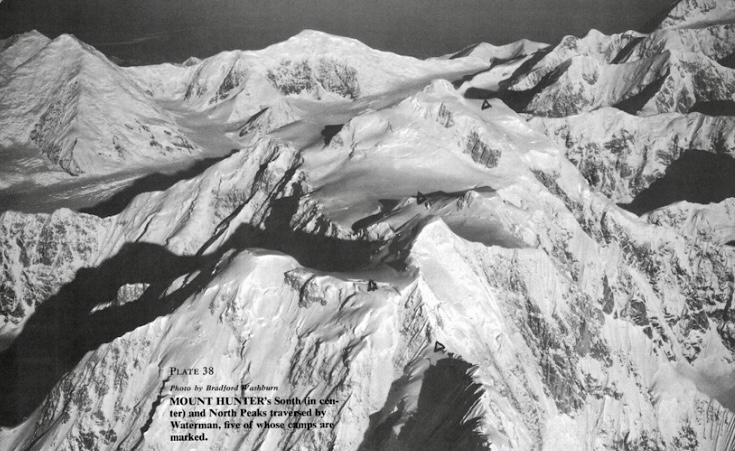

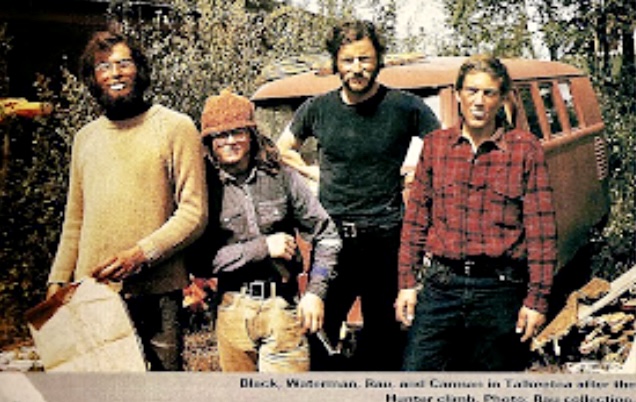

In 1978, American mountaineer Johnny Waterman completed the first solo ascent and traverse of Mount Hunter’s twin summits in Alaska. His grueling 145-day odyssey redefined the limits of solo mountaineering, showcasing incredible endurance and skill. We examine the climb, its significance, and Waterman’s legacy.

Johnny Waterman

John Mallon Waterman, better known as Johnny Waterman, was born in 1952. He grew up climbing with his father, Guy Waterman (a mountaineer and conservationist who also wrote several books about the outdoors), and his older brother Bill.

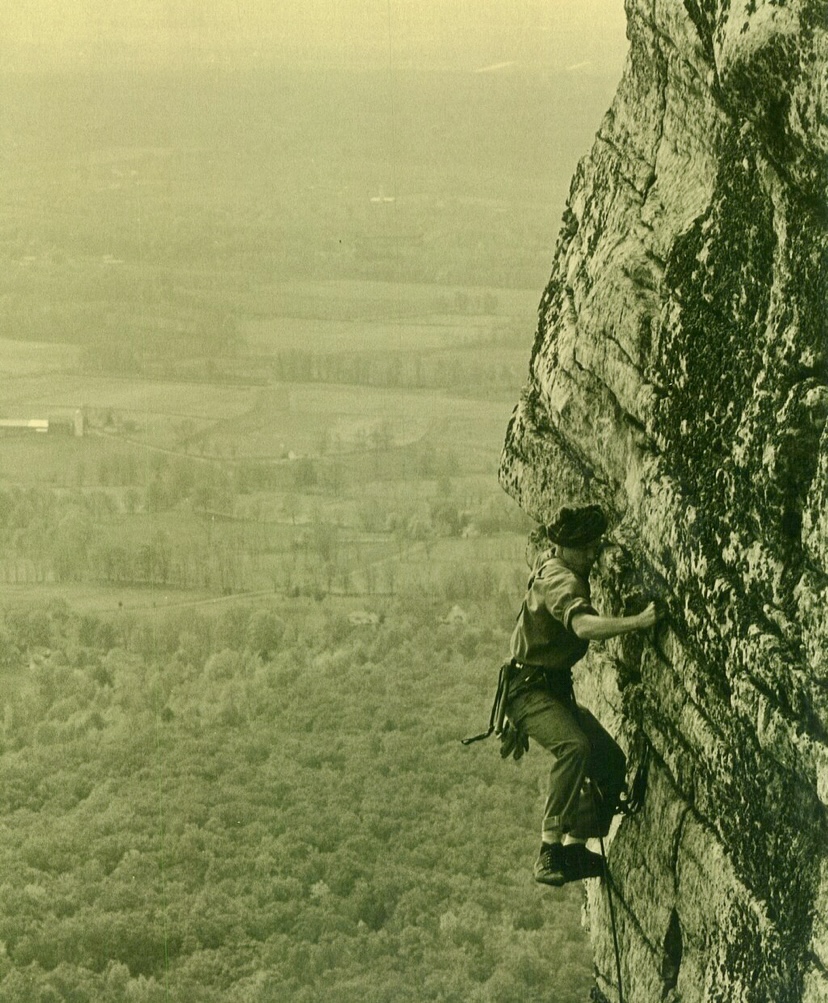

When Johnny Waterman was still in his teens, he began backpacking and rock climbing in New York and New England. He led a 5.10 route (Retribution) in the Shawangunk Mountains in New York State at 15. At 16, he climbed McKinley’s West Buttress with the Appalachian Mountain Club.

According to Bradley Snyder for the American Alpine Journal, Waterman was years ahead of mainstream mountaineering: "John might have coasted through mountains on sheer natural ability, but he took the craft of climbing seriously, and trained himself to be a fast, safe, consistent climber on any terrain."

Notable climbs

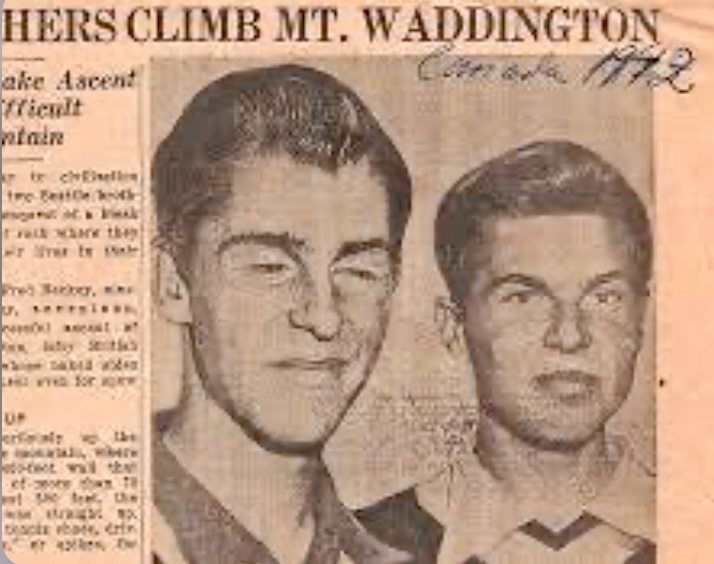

After high school, Waterman made trips to England, Scotland, Canada, the Alps, and Turkey, and carried out several remarkable ascents. In Canada, he made the second ascent of Snowpatch Spire’s South Face.

Waterman made the first solo ascent of the committing VMC Direct route on 1,244m Cannon Mountain in New Hampshire, a mind-blowing feat.

He ascended The Nose of El Capitan, soloed the Grand Teton’s North Face, and carried out the first south-to-north traverse of the Howser Towers.

He made the first ascent of Mount McDonald’s North Face and the first ascent of the East Ridge of Mount Huntington. On Mount Robson, he made the third ascent of the North Face.

Mount Hunter

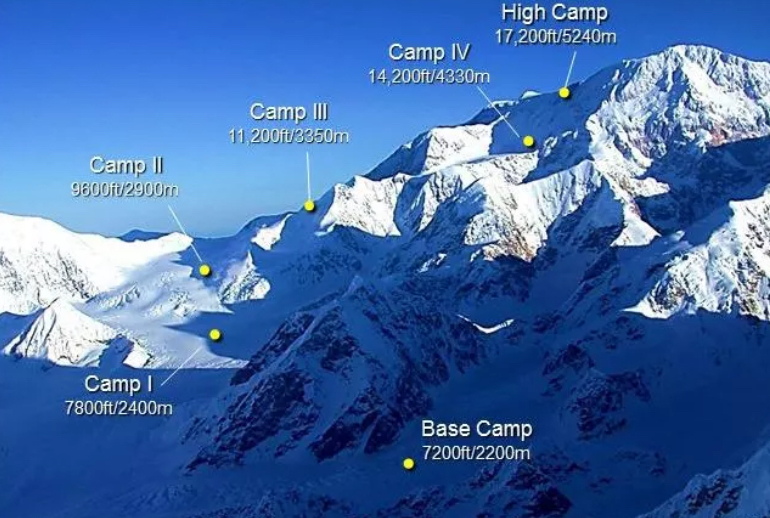

Mount Hunter (also called Begguya) is 13km south of Mount McKinley, in the Alaska Range within Denali National Park.

Begguya means child, or Denali’s child, in the local Dena’ina Athabascan language. It is famous for its technical difficulty, steep faces, and remoteness. Elite alpinists are drawn to its challenging routes, extreme weather, and beauty.

Mount Hunter has two summits: the North Summit at 4,442m and the South Summit at 4,255m. A high plateau connects the two summits, making the traverse an unusual challenge. Its climbing history features several bold ascents, technical innovation, and few summits, especially compared with McKinley.

Fred Beckey, Heinrich Harrer, and Henry Meybohm made the first ascent of Mount Hunter in 1954 via the west ridge from the Kahiltna Glacier. They topped out on the North Summit on July 3. Their multi-day route passed over crevassed glaciers, steep snow slopes, and a corniced ridge.

A bold attempt on Mount Hunter in 1973

In May 1973, Waterman and partners Dean Rau, Don Black, and Dave Carman attempted the first ascent of the south face-south ridge route of Mount Hunter. Waterman, then 21 years old, aimed for the 4,257m South Summit.

On May 29, Black, Waterman, and Carman were 61m below the South Summit when they mistakenly halted at a gendarme because of an approaching storm and confusion with the North Summit. (Rau had stopped lower down.)

Their route from the south col (3,200m) comprised three demanding sections: a complex lower rock ridge requiring 914m of rope and 40 anchors; a steep middle mixed face with ice-filled cracks; and an upper snow-ice ridge with unstable ice and minimal belays.

A storm trapped the climbers in a snow cave for days, with high winds and almost zero visibility. The climbers were running out of food, and Waterman had frostbite. The exhausted trio retreated from below the South Summit. Despite the failure, Waterman decided to return one day to solo Mount Hunter.

After 1973, Waterman moved to Fairbanks, Alaska. He preferred solo climbing because he struggled to find equally skilled partners, and possibly because of a tragic event in 1973. Johnny’s beloved brother, Bill, who had lost his leg in a railroad accident in 1969, disappeared in Alaska in 1973. Bill was only 22 years old.

After this, Waterman became more isolated and increasingly climbed solo.

Mount Hunter solo traverse, 1978

Waterman returned to Mount Hunter alone in the spring of 1978.

"My vendetta with Mount Hunter started in the late 1960s, with Bradford Washburn’s pictures in the American Alpine Journal," Waterman wrote in his climbing report for the AAJ.

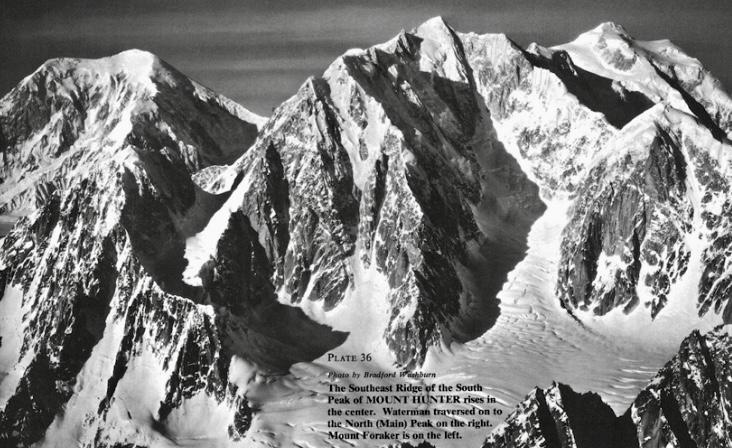

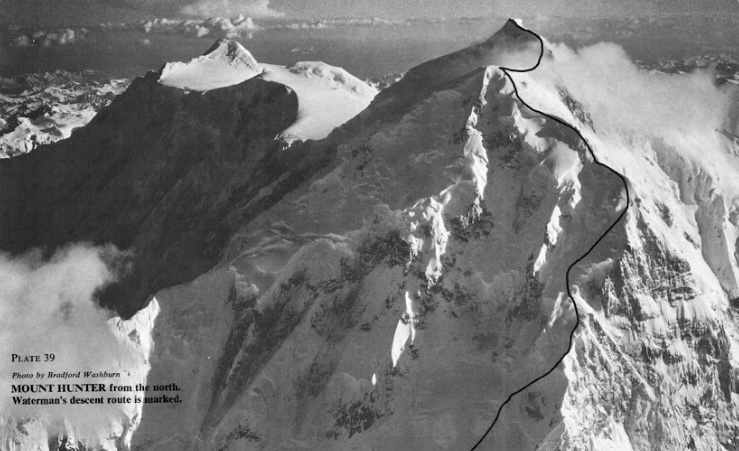

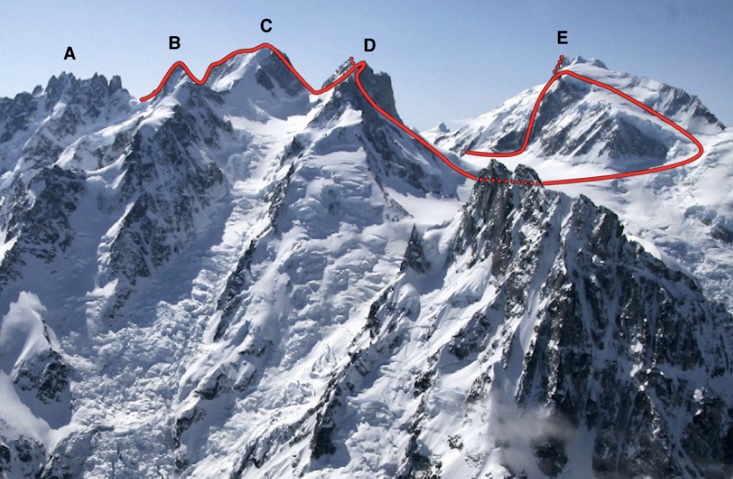

Driven by a decade-long obsession, Waterman began a solo south-to-north traverse. Starting on March 24 from the Tokositna Glacier’s cirque at 2,438m, he aimed to climb the 1,433m Central Buttress of the south face (referred to as the southeast spur in mountaineering literature), then traverse the summit plateau and descend the north spur.

He had 1,097m of rope and more than 350kg of gear, including food calculated to provide 5,000 calories a day.

The climb

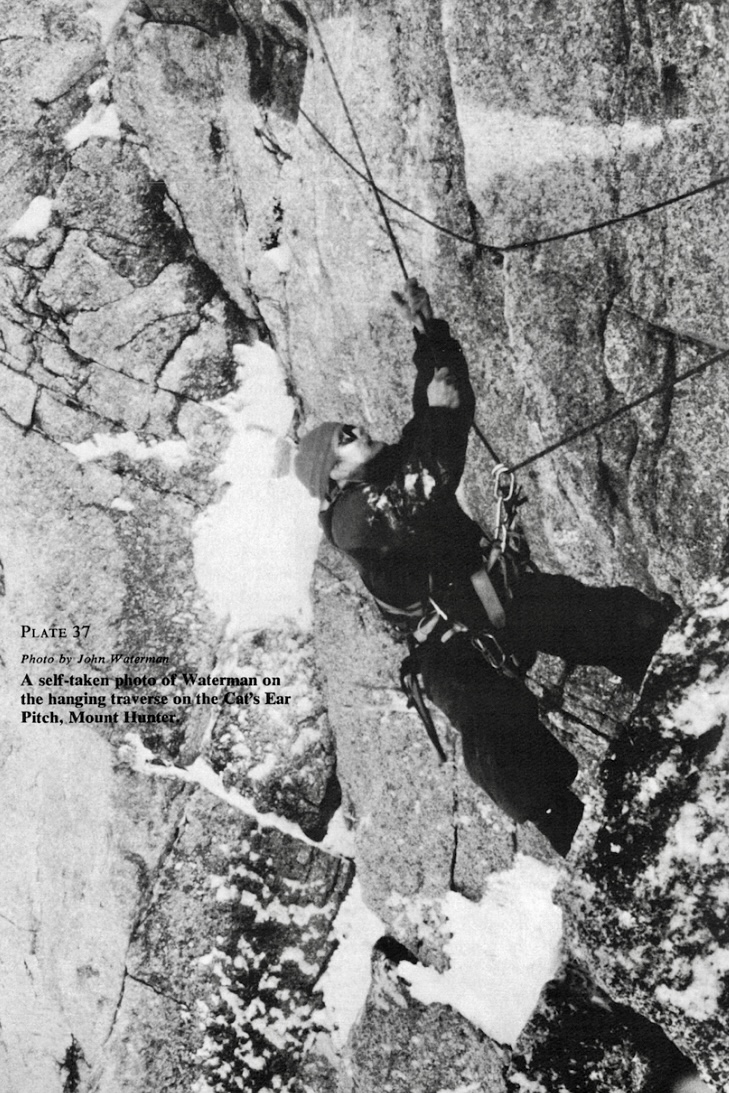

Waterman adopted an expedition-style approach, shuttling his 272kg base camp up each section, reusing rope to cover a route requiring 3,658m. The ascent involved 12 camps and 12 round trips per section.

The Central Buttress was mostly snow and ice, with rock steps and a 107m rock cliff. Section one included a 366m gully, and section two tackled a 152m technical crux, including a 24m pinnacle and a 90m gully. On April 11, day 18, he reached Camp 3.

Next came a 488m corniced arete, featuring a 30m headwall and ice pinnacle, which he finished on May 6. The next section wasn’t easy, either. He climbed steep terrain, joining the south ridge at 3,871m on May 26.

During the climb, Waterman suffered frostbite, lost a contact lens, and had a lice infestation. He dealt with fraying ropes, cornice collapses, and food shortages, dropping to two-thirds rations by June. A resupply on June 20 (day 88) provided 36 days of food.

By June 12, he reached the summit plateau after navigating a 213m ice arete. He topped out on the South Summit on July 2 after 101 days. After traversing the two summits, he reached the North Summit on July 26.

He descended by the north spur, arriving at his fly-out site 43 days later. His solo expedition took an astonishing 145 days. According to his report, Waterman used 40 ice pitons, pickets, and flukes, and 20 rock anchors.

His new route was the first solo ascent and the first solo traverse of the peak. He endured loneliness, rage, and frustration, but persevered, managing limited food supplies to complete his climb.

After the climb, Waterman’s mental health deteriorated. He displayed obsessive and delusional behavior. His past climbing feats convinced him he was invincible.

Disappearance

In the spring of 1981, Waterman targeted McKinley solo via the East Buttress. He planned to climb up the northwest fork of the Ruth Glacier, a route prone to crevasses and avalanches. Waterman began on April 1, carrying minimal supplies. He was last seen on April 19 at 3,350m.

Helicopters and ground rescue teams found only some tracks and an abandoned campsite. He might have suffered a fatal crevasse fall, died in an avalanche, or, with minimal gear, perished of exposure. Waterman was 29 years old when he disappeared.

Aftermath

Waterman’s father, Guy Waterman, committed suicide in February 2000, intentionally freezing to death on Mount Lafayette in New Hampshire. Laura Waterman, Guy Waterman’s wife (and Johnny Waterman’s stepmother), created The Waterman Fund after his death. The fund promotes wilderness preservation through education, trail maintenance, and research. The present an annual Guy Waterman Alpine Steward Award, honoring those dedicated to protecting the region’s mountain wilderness.

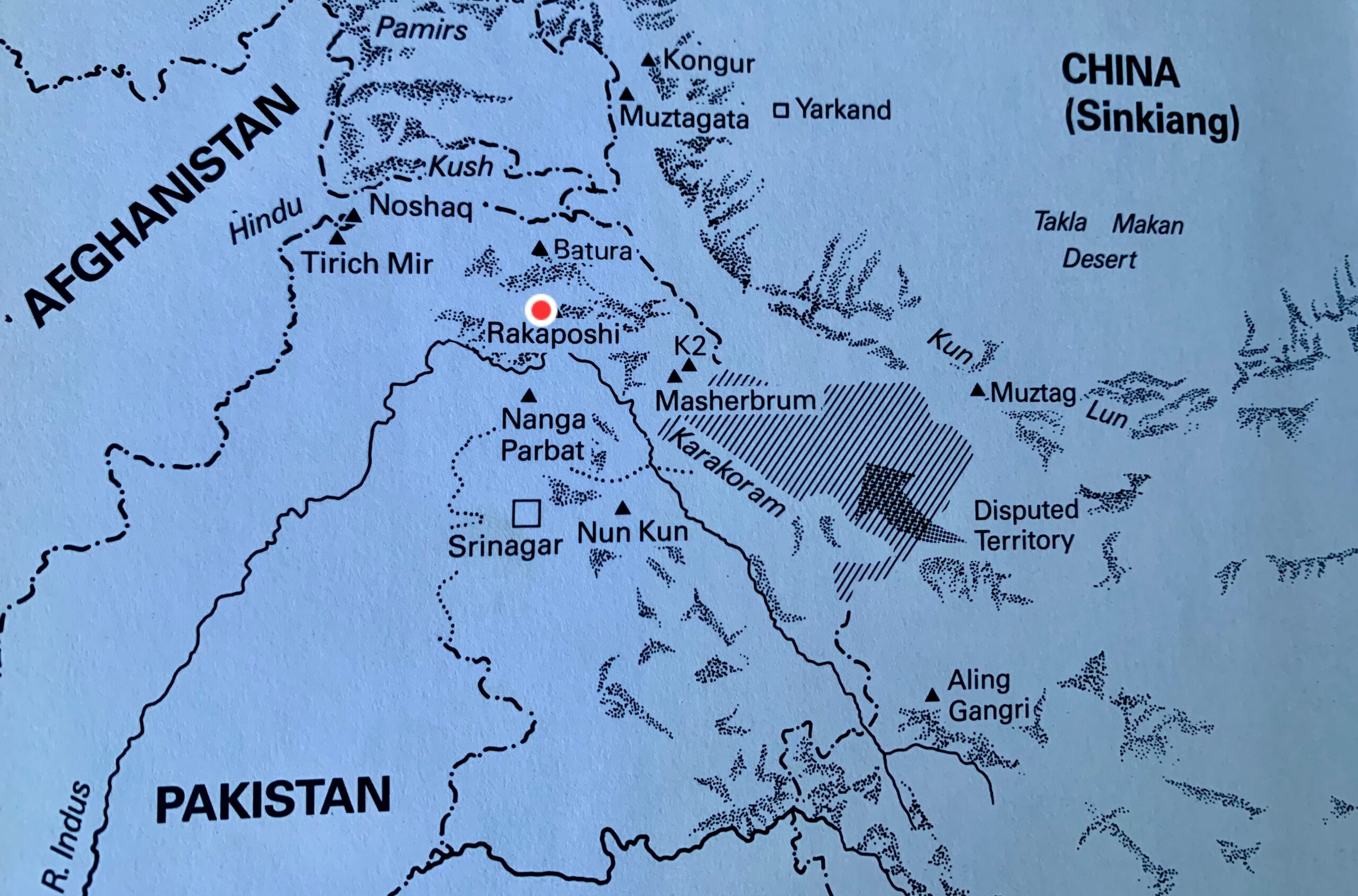

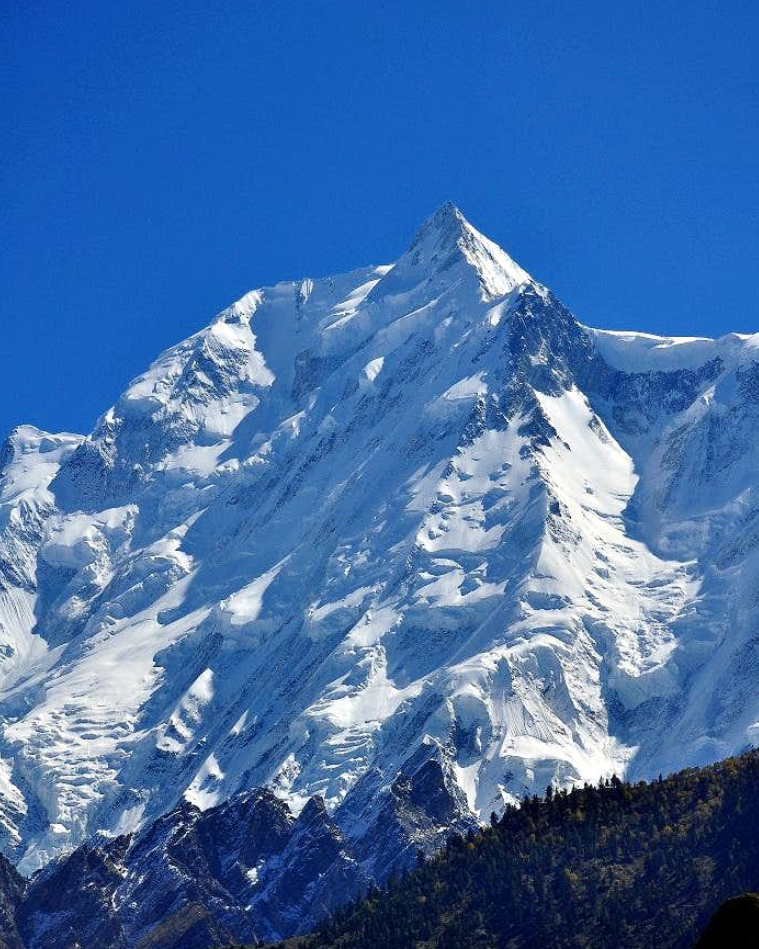

At 7,788m, Pakistan's Rakaposhi is a formidable peak that sees little climbing activity. Fewer than a dozen parties have topped out. Its steep slopes, technical difficulty, and unpredictable weather deter most climbers.

Rakaposhi is the 26th highest independent peak in the world and the 12th highest 7,000’er. It lies in the Lesser Karakoram mountains in Gilgit-Baltistan. The closest 8,000m peak is Nanga Parbat, roughly 110km south-southwest of Rakaposhi.

The mountain is also known by the name Dumani, which comes from the local Burushaski language. It translates to "Mother of Mist" or "Mother of Clouds" because the peak is often shrouded. The name Rakaposhi derives from a Burushaski term meaning "shining wall."

Rakaposhi rises 5,800m in just 11.5km of horizontal distance from the Hunza River.

The first foreign explorers arrived at the end of the 19th century. Martin Conway explored Rakaposhi's southern side in 1892. Conway concluded that although the upper part of Rakaposhi could be climbable, reaching the upper crest of the peak by any of the supporting ridges would be difficult and dangerous.

In 1938, British mountaineer and explorer Michal Vyvyan and his partner Reginald Campbell Secord approached the peak from the west. They ascended a small 5,800m forepeak at the end of the northwest ridge.

The first determined attempts

In 1947, Secord returned with Bill Tilman and two Swiss climbers to attempt the southwest spur. They abandoned their attempt at 5,800m, where a great gendarme blocked the route. From there, Tilman observed a 600m wall of snow and ice, which they called Monk’s Head.

The team then tried the northwest ridge. Later, they inspected the southeast face, the north face, and the east face but found them all impracticable.

In the summer of 1954, two expeditions arrived at Rakaposhi.

An Austrian-German party led by Mathias Rebitsch attempted the southwest spur. They reached 5,200m, but extreme snowstorms, high winds, and difficult ice conditions forced them to retreat. They agreed with Conway's conclusion from 60 years earlier: The mountain seemed unclimbable from that direction.

In the same season, an expedition from the Cambridge University Mountaineering Club led by Alfred Tissieres attempted the same route. They climbed the Monk’s Head but turned around in bad weather at 6,340m.

In 1956, Mike Banks led a four-man British-American expedition to Rakaposhi. They were the first expedition to go above 7,000m, reaching 7,170m on the southwest ridge. They made two further attempts later on that expedition but couldn’t progress higher.

"We were all much impressed by Rakaposhi," Richard K. Irvin recalled in his report for the American Alpine Journal. "It’s a very long climb, and it is a real climb, not just pushing along. This route certainly can be climbed to the summit, and there probably is no other way by today’s Himalayan standards."

The first ascent

In 1958, two years after his first attempt, Banks returned to the mountain, leading a British-Pakistani Forces Expedition that included Scottish mountaineer Tom Patey.

The climbers chose the southwest spur for their ascent. They established Base Camp on May 20 at 4,267m.

Over the next month, relentless snowfall, avalanches, and blizzards hampered their efforts to put up six camps to the summit. Despite the storms, the team set camps up to 5,791m. On June 20, seven climbers and some Hunza porters ascended the slope of Monk’s Head, and the porters carried loads beyond it.

On June 23, three climbers carried supplies from 6,400m to 7,010m, allowing Banks, Patey, R.F. Brooke, and R.N. Grant to camp at 7,010m. On June 24, Brooke and Grant supported the summit party of Banks and Patey. Banks and Patey then established a high camp at 7,315m.

On June 25, Banks and Patey set out for the summit in a strong blizzard. Battling intense cold, they climbed for five hours and finally topped out.

Patey suffered minor frostbite on his hand and Banks on his feet. After summiting, the duo descended quickly to their high camp. Three days later, the entire team returned safely to base camp.

This first ascent of Rakaposhi was carried out without supplemental oxygen.

The first repetition of the southwest spur

The Belgian Club Alpin Beige Expedition repeated Rakaposhi’s southwest spur route in 1983. After great difficulty climbing the Monk’s Head slope, Bertrand Borrey, Daniel Bogaert, Arthur Delobbe, and high-altitude porter Sultan Ullah Baig topped out on August 2.

According to the expedition’s report in the American Alpine Journal, the climbers started an avalanche while descending. The avalanche swept away Michel Bodard, who fell 200m and suffered a broken leg and thumb, a punctured lung, a concussion, and multiple contusions. He was lowered to Camp 4 (at 6,400m), and two days later, a helicopter picked him up at 6,140m.

Their bad luck didn't end there. On August 5, high-altitude porter Sultan Ullah Baig insisted on descending alone to give his countrymen news of the summit success. He disappeared between Camp 2 and Camp 1. The team searched for five days but never found his body.

New route in 1979

On June 5, 1979, a Polish-Pakistani expedition led by Ryszard Kowalewski established a base camp at 3,810m in a side basin of the Biro Glacier.

On June 14, a gigantic ice avalanche from a collapsed wall devastated the tents at base camp, but the expedition continued. The party tackled the northwest ridge, previously scouted to 6,005m by an Irish expedition in 1964.

They set up Camp 1 on June 6, placing it at 4,907m at the base of the northwest ridge. They established Camp 2 at 6,203m on June 26.

The party then descended 61m to a snow terrace below the summit pyramid, where they set up Camp 3 at 6,500m. Crossing the terrace to a col at the end of the southwest ridge took between six and eight hours. Here, on June 30, they placed Camp 4 at 7,102m.

On July 1, Kowalewski, Pakistani climber Sher Khan, and Tadeusz Piotrowski climbed to the summit in 18 hours. The next day, after a miserable night with six in a tent, Andrzej Bielun, Jacek Gronczewski, and Jerzy Tillak also topped out, reaching the summit in only six hours.

On July 5, with the higher camps empty, Anna Czerwinska and Krystyna Palmowska summited unroped through wind and snow. This marked the second-highest "ladies-only" climb after Gasherbrum II in 1975 by Halina Kruger and Anna Okopinska. The two women climbed unroped because it was too cold for one to wait for the other.

The Polish-Pakistani success was the second documented ascent of Rakaposhi.

A solo climb

In 1995, Anibal Pineda of Colombia made a notable solo climb via the northwest ridge. According to the American Alpine Journal, Volker Stallbohm was the expedition leader.

The extremely difficult north spur

In the summer of 1979, a Japanese expedition from Waseda University arrived. Led by Eiho Otani, they summited via the north spur, a steep route on the north face.

They established their high camp on an ice step at 7,300m. From there, Otani and Matsushi Yamashita started their summit push. The duo bivouacked at 7,600m and summited on August 2. On top, they found evidence of the Polish ascent. The expedition climbed siege-style, with 5,000m of fixed rope, over six weeks.

This extremely difficult route had been attempted in 1971 and 1973, both led by Karl Herrligkoffer.

The same route saw its first alpine-style ascent in 1984. Canadians Barry Blanchard and Kevin Doyle and South African Dave Cheesmond survived lightning strikes that knocked them unconscious during their summit push. This was an outstanding ascent.

Other ascents

In the summer of 1986, a Dutch expedition climbed a variation of the northwest ridge. This route was a shorter line in the lower section and joined the 1979 Polish route at 6,000m.

In the summer of 1997, four members of an Iranian party summited via the southwest spur.

A Piolet d’Or climb

Another successful ascent took place in 2019. World-class Japanese climbers Kazuya Hiraide and Kenro Nakajima tackled the unclimbed south face before transitioning to the southeast ridge.

Starting from their base camp at 3,660m, Hiraide and Nakajima, climbing alpine style, reached 6,800m after three days. There, they waited out bad weather and summited on July 2 in a single day. They descended to Base Camp on July 3. In 2020, they were awarded the prestigious Piolet d’Or for their climb.

The last ascent of Rakaposhi was in September 2021. Czechs Jakub Vicek and Petr Macek, and Pakistani Wajidullah Nagri summited Rakaposhi via the southwest spur. The controversial expedition did not have permits and required a helicopter rescue.

In 1985, an Austrian expedition led by Eduard Koblmuller climbed Rakaposhi’s 7,010m east peak via the north buttress. On August 1, Koblmuller, Fred Pressl, and Gerald Fellner summited in alpine style. During the two-day descent, Fellner slipped at 4,700m in bad weather. He fell 100m down an ice slope and sustained fatal injuries. Despite medical attention, he died in the night.

Rakaposhi’s climbing history shows that even after decades, new routes remain for bold climbers.

The remarkable French alpinist Chantal Mauduit would have turned 61 today, but her passion for high-altitude mountaineering led to her premature death at age 34. Here, we explore her climbs and her fatal expedition to Dhaulagiri I.

Early life

Mauduit was born in Paris on March 24, 1964. At five, she moved with her family to Chambery in the Savoie region of the French Alps. This relocation introduced her to the mountains, where she began hiking in summer and skiing in winter.

At 15, her mother passed away from cancer. Seeking solace, Mauduit turned to climbing, starting with the Alps. By 17, she had already climbed the North Face of the Grandes Jorasses, the Drus, and the Matterhorn.

In the early 1990s, Mauduit ascended the Directissime Jori Bardill route on the Central Pillar of Freney in the Mont Blanc massif with Catalan climber Ernest Blade.

In July 1992, with Blade, Araceli Segarra, and Albert Castellet, she climbed the Bonatti Pillar on the Petit Dru. They finished the famous 800m route in eight hours. One year later, Mauduit completed the Walker Spur on the Grandes Jorasses in a single day from Chamonix.

In the mid-1990s, Mauduit did the Devies-Gervasutti route on the northwest face of Ailefroide Occidentale (3,954m) in the Ecrins massif. This 1,050m line is known for its remoteness and technical difficulty.

Next, Mauduit went to the Andes. She climbed 5,495m Nevado Urus and took part in an expedition to 6,768m Huascaran. She made the Sajama Traverse in Bolivia (6,542m) and ascended Mount William in Antarctica.

Himalaya and Karakoram

Her focus then shifted to the Himalaya, where she chose to climb without supplemental oxygen.

"Climbing without oxygen is my ethics. When you use [oxygen] during an ascent, you necessarily miss very strong, very intense moments, both visually and audibly. All the senses are then heightened," she told Le Monde newspaper.

On Aug. 3, 1992, aged 28, Mauduit summited K2 via the Abruzzi Route without supplemental oxygen. She became just the fourth woman to do so.

Her descent was harrowing. A storm caught her near Camp 4 at around 8,000m, and she became snowblind. Americans Ed Viesturs and Scott Fischer -- who had struggled to scrape together enough money for their expedition -- abandoned their summit bid to save her.

Controversy

Back at Base Camp, Mauduit didn’t thank Viesturs and Fischer but instead celebrated her summit success as if the rescue had never taken place.

"So now Chantal was celebrating with the Russians. We’d hear their cheers and revelry as we [Viesturs and Fischer] lay silent in our tents. Scott and I hadn’t been invited to the party," Viesturs wrote in his book No Shortcuts to the Top.

More big peaks

In 1993, Mauduit summited Shisha Pangma and Cho Oyu without supplemental oxygen, burnishing her 8,000m reputation.

On April 28, 1996, Mauduit topped out on 7,138m Pumori. After that, she climbed two 8,000m peaks in the same season. On May 10, she climbed Lhotse and reached the top alone, leading some to question her summit success because of a lack of proof. This climb took place during the infamous 1996 Everest disaster, and Mauduit witnessed the tragedy that killed several climbers, including Scott Fischer.

Ed Viesturs told Elizabeth Hawley of The Himalayan Database that he had seen Mauduit enter into a gully and return soon after, casting doubt on her summit. Mauduit's sponsors were likely pressing hard for her to succeed after her failure one year earlier on Everest. However, the summit was officially accepted, and she became the first woman to summit Lhotse.

Two weeks after Lhotse, Mauduit summited Manaslu, topping out alone again. According to Hawley, Mauduit was accompanied by Ang Tshering Sherpa, but Ang Tshering ran out of energy on their final push on May 24. He had been breaking trail for hours in deep snow. Mauduit's summit marked her fifth 8,000’er.

Her sixth 8,000m summit came in 1997 on Gasherbrum II, again without bottled oxygen.

In the autumn of 1996, Mauduit attempted Annapurna I but aborted above high camp in bad conditions.

Seven attempts on Everest

Between 1989 and 1995, Mauduit made seven attempts on Everest without bottled oxygen. She never summited the world's highest peak.

On her last attempt in 1995, she suffered serious altitude sickness. After almost collapsing during a summit push, she was carried down by fellow climbers and needed extra oxygen. This event, like the K2 rescue, drew criticism for her reliance on others.

Mauduit always pushed very hard, but on several occasions, she started strong but ran out of energy and needed help.

Despite these incidents, Mauduit’s successful 8,000m climbs without supplemental oxygen place her among the elite of her era.

Death on Dhaulagiri I

Mauduit had already attempted Dhaulagiri I in the autumn of 1997, but she aborted above high camp. In the spring of 1998, she returned to try again.

This was her last expedition. Mauduit and 45-year-old Ang Tshering Sherpa died, possibly between May 11 and 13. Climbers found their bodies in their tent at Camp 2 (6,500m). Ten Sherpas brought her body down, and it was flown to Kathmandu and then on to France.

During a summit push, other teams on the mountain had retreated to Base Camp because of avalanche danger and bad conditions. Yet Mauduit and Ang Tshering stayed in Camp 2.

An autopsy in France confirmed the cause of death as a broken neck, likely from a rockfall or small avalanche. The Italian climbers who found her body also believed this was the most likely cause of death.

Ed Viesturs was also on Dhaulagiri that season and suggested carbon monoxide poisoning from a stove could have killed her. He reasoned that there were no clear signs of an avalanche at Camp 2.

The Italian climbers had found Mauduit and Ang Tshering's tent covered in snow. They had to dig the tent out to look inside and found the pair in their sleeping bags. This accumulated snow might have broken Mauduit’s neck, the Italians suggested. Yet Ang Tshering's neck was not broken.

Mauduit’s family and friends chose to trust the results of the autopsy.

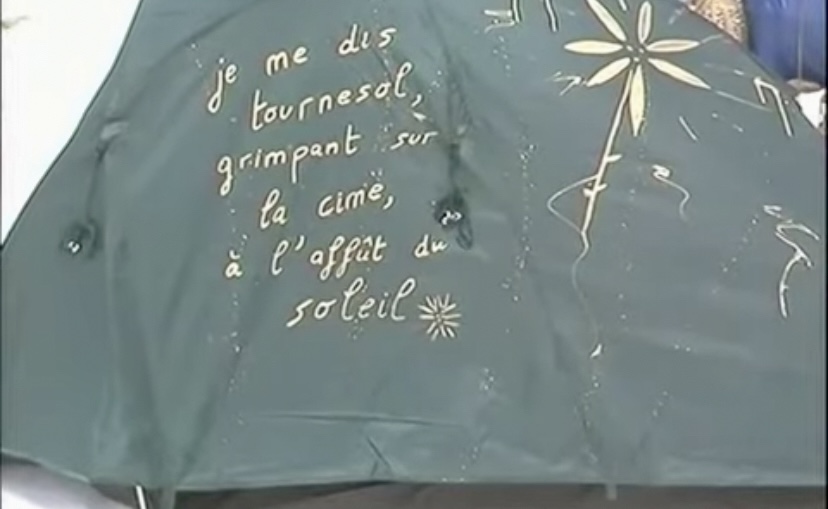

A poetic soul

Mauduit studied physiotherapy but abandoned it for a life in the mountains, living nomadically between expeditions. She carried books by Rimbaud and Baudelaire on climbs, wrote poetry on her tent, and spoke about her experiences with lyrical depth.

In 1997, she published J’habite au Paradise (I Live in Paradise), a book blending impressions of her climbs with reflections on the cultures she encountered.

"Chantal Mauduit was a very interesting woman,” Elizabeth Hawley once wrote. "When she arrived here, she named each of her expeditions after a flower she had drawn on her tents. She was flamboyant."

Mauduit’s approach to mountaineering was unconventional. She prioritized personal experience over logistical teamwork. But her infectious optimism and comfort in the mountains earned her admiration. Viesturs wrote that everybody loved Mauduit for her happy character.

After her passing, friends and family founded the Association Chantal Mauduit Namaste, which established a school in Kathmandu, honoring her generosity toward Nepalese communities.

Below is a short video showing something of her character.

On March 22, 1966, American climber John Harlin fell 1,000m to his death on the Eiger’s North Face. He was just 600m from completing his ambitious Direttissima route. Fifty-nine years later, we look back at his career, marked by innovation and a deep connection to the Alps.

From fine arts to pilot