On Friday, March 21, the sun finally returned to the North Pole, casting its first rays on a vast, frozen nothingness. Three days later, according to sources affiliated with Barneo, the annual North Pole season has been canceled for the seventh year in a row.

For those unfamiliar with Barneo Ice Camp, it’s a temporary base that appears each year on the drifting sea ice near the North Pole. It's built for the kind of people who respond to the question, “Would you like to spend $40,000 to be very cold?” with an enthusiastic yes.

Scientists, marathoners, adventurers, the occasional prince or sheik — people with expensive parkas and a deep need to suffer in extreme environments — flock to it. That is, unless the season is canceled, which has become a trend in recent years.

For a moment, it seemed like this year would be different. The internal squabbling between Moscow and Krasnoyarsk had resolved in favor of Moscow. This, in turn, meant victory for the Frederik Paulsen Group, which owns Barneo.

Politics and Barneo

What was this internal squabble? Last year, the North Pole season didn’t just fail because of a cracked runway and bad weather. There was a power struggle behind the scenes between two groups: the Krasnoyarsk faction –- regional players who wanted control over part of the Barneo operation and attempted to use their local influence to block access to the route through Khatanga -- and the Paulsen Group/Barneo AG –- the Moscow-backed organization in charge of the North Pole season.

In 2024, the Krasnoyarsk side used bureaucratic and security excuses (claiming Khatanga was a secret military zone) to trap international athletes and travelers in Krasnoyarsk and prevent them from reaching the North Pole.

This year, however, that conflict was settled in favor of Moscow and Barneo AG, likely because Krasnoyarsk lacked the political and financial backing to fight back. Essentially, the Paulsen Group has won control, ensuring that this kind of interference won’t happen again.

Geopolitics also played a big role in the failure of 2024 North Pole season. Russia’s internal narrative painted the U.S. as an enemy, which made organizing international events like Barneo, popular with Westerners, more complicated.

Now, however, Russia’s state rhetoric has changed, portraying the U.S. as a sort of ally rather than an antagonist. This shift has likely made it easier for Barneo organizers to proceed without political resistance.

All this made Barneo seem at least possible this year. But it still wasn't enough. Suddenly, it's canceled again.

Warning signs

There were warning signs. First, news trickled in that construction of the camp had been delayed. Then came the real kicker: Murmansk airport — normally the launch pad for Barneo operations — was going to be closed for a week. Why? Because Vladimir Putin was attending the International Arctic Forum, and when Putin is in town, flights are grounded.

To the untrained eye, one week might not seem like a deal breaker. But in the high-stakes game of building an entire pop-up city on a chunk of floating ice, that’s all it takes. Delay the start, and suddenly, the weather shifts, the ice cracks, and your $40,000 North Pole dream melts away like a popsicle.

So here we are. Another year, another cancellation. Was it logistics? Politics? Who’s to say?

What is certain is that the adventurers who planned to run, ski, dive, or dogsled near the North Pole will now have to wait until at least next year. But don't hold your breath.

I opened the Barneo Ice Camp website today, and for the first time since the camp was launched in the early 1990s, the home page was in Chinese. My Mandarin skills are questionable at best, but I could still gather the gist: This year, the North Pole is going to have a Chinese vibe.

In a way, it's understandable. Unlike Americans and Europeans, the Chinese aren’t afraid of being taken for spies and added to Russia’s “exchange fund” — a handy collection of foreigners to arrest and use as bargaining chips to trade for their own agents captured in the West. The Chinese also have the money for what’s being marketed as the Adventure of the Century. After an eight-year closure, the North Pole has become an even more exclusive experience.

We didn’t used to have heated toilets

I remember the old days, when insurance policies didn’t come with a price tag that looked like a down payment on a house, when we didn’t have giant Antonovs swooping in with their short-runway capabilities, and when there were no luxury toilet facilities at 89 degrees north.

People flew in on the old AN-2s, refueling along the way. Those planes are probably still out there somewhere, parked in a snowdrift, waiting for the moment they can step in when the AN-74s inevitably run into trouble again — as in 2019 when the whole Barneo season got canceled because a Ukrainian-owned AN-74 wasn’t allowed to land. That was back when the geopolitical nightmare at the Pole was just warming up.

Can you get to the North Pole without Russia? No.

Some people have asked if they can get to Barneo without traveling through Russia. Theoretically, sure — Canada is right there, and you don’t need Russian airspace clearance to fly from Resolute Bay to the Pole.

But practically? No. Kenn Borek Air, the local charter airline, doesn’t offer that service anymore. And even if they did, you’d still need permission to land at Swiss-owned Barneo, which is somehow under Russian jurisdiction. No way around that unless you’re planning a surprise arrival, which I wouldn’t recommend.

Last year, the season fell apart just as tourists were gathering in Krasnoyarsk. Officially, Camp Barneo and some of the polar guides blamed bad weather and an irreparably broken ice floe. But nevertheless, three Russian parachutists, Mikhail Korniyenko, Alexander Lynnik, and Denis Yefremov, threw themselves from an Ilyushin-76 plane from the Earth's stratosphere to the North Pole and were enthusiastically welcomed at Barneo.

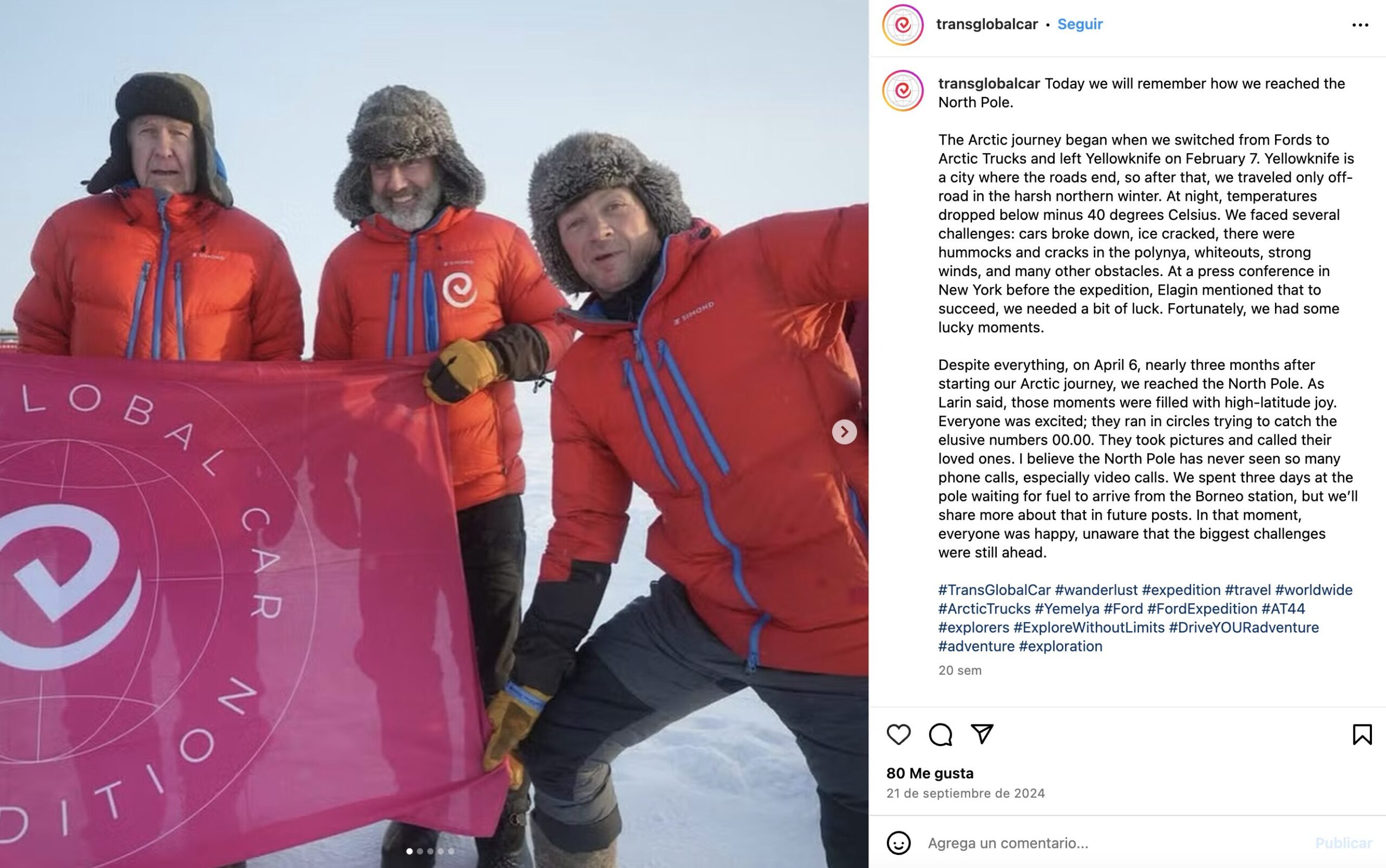

The Transglobal Car Expedition also used Barneo’s services. In their Instagram blog, they mentioned that the real reason wasn’t the ice or the weather. It was that foreigners weren’t getting clearance to pass through Russia’s top-secret Arctic.

“In late March, Barneo began deploying its station, dropping equipment on the ice near the North Pole, including our cargo," the Transglobal Car Expedition wrote. "We waited, delays stretched on, and eventually, we learned that Barneo hadn’t coordinated with border guards. Foreigners weren’t allowed to land in Khatanga.

"We realized this wasn’t going to be solved anytime soon, so we decided to just take our package...By then, the station was shutting down for the year. We realized how close we had come to disaster. No fuel, no food, and no good backup plan.”

People in the industry recently told me there was some major drama between Swedish billionaire Frederick Paulsen, who owns Barneo, and his ambitious competitors in Krasnoyarsk. Apparently, it played a role in the shutdown. Dirty games? Maybe.

This year, Paulsen seems to have won, meaning that he gets the tourists, while those Krasnoyarsk competitors get the science expeditions. It remains unclear what this actually means or whether things won't change when Barneo opens. In Russia, things often remain what Winston Churchill called a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma.

The cost of being an explorer in 2025

So, how much will this year’s North Pole cost you?

For $58,000, you can sign up for the North Pole Double Degree trip (April 1–18). That covers your journey from Krasnoyarsk to Krasnoyarsk and skiing from 88˚ to the North Pole. Visas, flights, hotels, and accommodations in Khatanga are extra.

Khatanga's Hotel Mammoth Inn — also owned by Paulsen — is already fully booked from April 1 to May 9. But if you’re lucky (and “approved” by Camp Barneo), you might still get a room. It seems that the adventure now requires medical evacuation coverage, while search-and-rescue insurance is optional. Which Western insurance company is offering coverage in Russian territory? That too in unclear.

With a lower budget, you can opt for the North Pole Last Degree Ski Adventure (April 1–14) for a cool $52,000. Risk level: “Very low.” Which is funny, because right below that, the travel company strongly recommends trip cancellation insurance due to the ever-present possibility of weather disasters, ice breakage, political issues, labor strikes, wars, revolutions, or terrorism.

The ultimate polar tourist experience

And for the champagne tourists, there’s the Ultimate North Pole Tour ($31,000). The description reads like a fever dream of excess:

"North Pole Deluxe takes you to the top of the world in style and comfort. Four jet flights, two helicopter flights, two nights in a hotel, and a night at Barneo Ice Camp give you the deluxe version of North Pole travel."

The itinerary includes:

- April 4, 2025: Arrive in Krasnoyarsk.

- April 5: Fly to Khatanga (3.5 hours) and check into the Mammoth Inn.

- April 6: Sightseeing at the Mammoth Ice Museum and something called the Fold Art Center (I have no idea what that is).

- April 7: A five-hour flight to Barneo, stopping to refuel at Cape Baranova. Transfer to heated accommodations before taking a helicopter to the North Pole.

The North Pole Marathon: cheap at just $25,000

And then there’s the North Pole Marathon — because why not run a race on a frozen ocean? Runbuk is trying to make it happen again, despite last year’s disaster when their clients never made it out of Krasnoyarsk due to permit issues.

But if they do pull it off, it’s the best deal in town. Sticking to the budget-friendly tradition started by Richard Donovan in the early 2000s, Runbuk is offering the full package for a mere $25,000.

Meanwhile, American polar adventurer Eric Larsen is still promoting his Ellesmere Island to North Pole expedition, set to begin on February 20. The only question is: will Barneo (on which their pickup depends) even exist?

When the Arctic wasn't a luxury destination

Thirty years ago, skiing to the North Pole was a different beast. This year marks the 30th anniversary of Richard Weber and Misha Malakhov's 1995 roundtrip ski from Ward Hunt Island to the Pole and back. No helicopters, no resupplies, no $50,000 insurance policies. No sled dogs, no guides.

On February 13, 1995, they left Ward Hunt Island. Eighty-one days later, on May 12, they arrived at the Pole. By June 15, after 108 days on the ice, they were back at Ward Hunt. Since historians now accept that the original claimants, Robert Peary and Frederick Cook, never reached the North Pole, Weber and Malakhov's journey is the only one to the Pole and back. Ever.

But that was another era. Now, the North Pole is less about survival and more about a five-star experience. But given all the problems in recent years, uncertainty still reigns.

It was like the circus had come to town. Only instead of elephants and acrobats, we had Donald Trump Jr. sitting alone at Nuuk’s swanky Hans Egede Hotel, a place where the heart of a whale costs more than most people’s rent. He was looking for extras, a local entourage. His cortege was eager to film "good people of Greenland."

Naturally, he didn’t invite the elites of Niels Hammekensvej — the kind of people who debate sealskin fashion while sipping aquavit and perfecting their nonchalant poses. No, these fine people were suspicious of MAGA hats. So Trump Jr. did what anyone in his position would do: He went rogue, wrangling his entourage from outside the Brugseni supermarket. This is where you find Nuuk’s real salt of the earth — people camping out under dim streetlights, the kind of crowd my sister-in-law Esther used to charm when selling her intricate seal mittens, kamiks, and sculptures made from walrus skulls.

Greenland is beautiful!!!

pic.twitter.com/PKoeeCafPz

— Donald Trump Jr. (@DonaldJTrumpJr) January 7, 2025

So, they dined on whale and who-knows-what, everyone smiling.

People were happy, and the food was free. A far cry from invasion threats — just some pricey whale meat and a little awkward charm. Call it soft power. And weirdly, it worked. Almost.

But not everything was a hit. Out of 300 "Make Greenland Great Again" hats, only seven were taken. And one of those was snatched up by Julius, the self-declared King of Greenland, who went viral for his "I am the King of Greenland Idiot" video. It was quickly dubbed The Meeting of Royals, with Trump Jr. and Julius posing awkwardly.

Cameras captured everything, from Trump Jr.’s signature smirk to the bewildered expressions of Danish officials. Trump Force One sat proudly at the airport, a stronger statement than any awkward dinner could make. It was Trump saying, "I’m here. Deal with it." Caught completely off guard, Denmark didn’t know whether to send a welcoming committee or special forces.

Trump's fascination is nothing new

Donald Trump Jr. says he came to Nuuk as a tourist. But Trump Jr.’s fascination with Greenland isn’t new. In 2015, he reached out to my husband, Ole Jorgen Hammeken — a polar explorer and Inuit elder — to plan an "extreme dogsled bow hunting expedition" in the North.

They met at Hemmingway Art Gallery in New York, introduced by its owner, Brian Gaisford, an Explorers Club member, and Trump Jr.’s neighbor in upstate New York.

Trump Jr. wanted to hunt muskox, but not in Kangerlussuaq, where the kill is basically guaranteed. Trump Jr. wanted fair game, preferably on the edge of the Earth itself. Ole Jorgen suggested exactly that. He invited him to go to Nunarsuup Isua, which translates to "The End of the Earth," known on maps by the colonial name of Cape Morris Jesup in Peary Land.

There, they planned to hunt muskox and climb Hammeken Point, the world’s northernmost mountain. It was a fever dream of a meeting. But then Trump Sr. ran for president, and all plans were shelved.

Nine years later, this past summer, while boating in Avanersuaq, Ole Jorgen found Trump Jr.’s business card in his sealskin jacket. It was torn and weathered, having survived countless storms and blizzards. All the storms that Trump Jr. has missed. A sign from the universe? Perhaps. Instead of venturing to Hammeken Point in Peary Land, Trump Jr. showed up in Nuuk.

A simmering anger

The fallout? Greenlanders reacted to Trump Jr.'s visit as they often do: stoically. Politicians raged, artists grumbled, and activists suggested locking him up in Greenland’s famously beautiful jail where Captain Paul Watson recently spent time. Regular folks shrugged. "This will pass," they said, the same way they talk about climate change or anything else life throws at them.

But Trump’s visit tapped into something deeper — a simmering anger with Denmark. Last year, a scandal shocked the nation: it was revealed that Danish doctors had secretly fitted thousands of young Kalaallit girls with IUDs in the 1960s and 1970s. No consent, no parental notification. Many of these girls, now women, including women in our own family, were unable to have children. The outrage was palpable.

Some are now calling for Greenland to shed its colonial name and embrace its true identity: Kalaallit Nunaat, the Land of the Kalaallit. Elisabeth Momme, a cultural leader and former director of the Ice Fiord Center in Ilulissat, summed it up: "If Burma can become Myanmar and Ceylon can become Sri Lanka, why can’t we be Kalaallit Nunaat instead of Grønland/Greenland?"

A complex history

Greenland’s history with America is complicated. Over a century ago, two explorers, Robert Peary and Matthew Henson, had relationships with young Inughuit women while trying to get to the North Pole. Peary’s choice, Aleqasina, was 13 at the time.

Peary and Henson left behind American-Inughuit children who grew up in poverty, wearing, at times, dogskin clothes — a sign of absolute destitution. The explorers never looked back.

Later, Peary’s and Henson’s descendants, and the rest of the Inughuit, were forcefully relocated. When the construction of the American air base at Thule began, authorities moved the Inughuit overnight from their beautiful home in Uummanaq to lifeless Qaanaaq.

Hivshu Ua, or Robert Peary Jr., Robert Peary’s great-grandson, is a keeper of Inughuit tradition. He reminded me that there is no word for "war" in the Inughuit language: "The colonizers’ word for war translates as 'the crazy man's work.' "

He also believes Greenland must negotiate to survive. "Nunarput (Our Land) has no chance of surviving if it does not negotiate. The invasion already happened. We just have to make the best of it," he explained.

When I asked him what can be achieved through negotiation, he said, "Demand that Inughuit style of life is secure for 30 years. Then we can use these three decades on transformation and adaptation."

Aviaq Henson is the great-granddaughter of Matthew Henson and his young Inughuit love, Akatingwah. Like Hivshu, she has traveled the world. She has lived between two worlds, the worlds of a dogsled and of modernity. Henson succeeded in finding a compromise. She can talk for hours about her people, the Inughuit, and their worldview, and she repeats again and again: There is no space for war in their sacred land.

"Most people in Greenland disagree with Trump. We still believe we can become an Independent Greenland, just like Iceland," Henson told me.

A PR moment

Trump Jr.’s visit, for all its absurdity, may have been Greenland’s biggest PR moment.

"This was a wake-up call for Denmark. For a hundred years, no one cared," Ole Jorgen said. "In the Danish mentality, we were still a colony. Some Danes were thinking, shall we keep them or just get rid of them? Kick them out? But now they are all on board. Everything changed in a day. Now, Denmark has to pay attention. So, thank you, Trump."

My friend in Siorapaluk, the Inughuit's greatest polar bear hunter, Peter Avike, says that if the situation ever gets dire, they have harpoons — many of them crafted entirely from narwhal tusk. But perhaps there’s another way.

During a conversation with Hivshu, I suggested he travel to Washington, D.C., meet Trump Sr., and arm himself not with a harpoon but with his kilaut — a skin drum made from a polar bear stomach. The kilaut represents consciousness; it’s a tool for communication and conflict resolution.

I proposed he challenge Trump to a drum-dancing duel, a quintessentially Greenlandic way to settle disputes. In this tradition, adversaries perform, and the one laughed at more by the crowd loses. Imagine Trump Jr. versus a seasoned drum singer. A fair game, no whale meat required.

And that, perhaps, is Greenland’s lesson to the world: In a land of ice and survival, the best weapon is laughter.

A couple of weeks ago, the North Pole/Barneo ice camp season fizzled out, leaving disappointed skiers, marathon runners, and champagne tourists. Environmentalists have pointed out that the whole idea of Barneo is out of date. Because while tractors and huts are parachuted onto the sea ice, they are not removed afterward. They are just left to drift, eventually breaking through the ice over summer and littering the bottom of the Arctic Ocean.

But not always. Before the climate started warming and when the Arctic Ocean ice was a lot thicker, ice near the North Pole drifted toward Greenland. And the ice sometimes even reached Cape Farewell, the southern tip of Greenland. It then continued to drift up the West Coast.

Once, in 1965, the ice brought a surprising bounty to some hunters in Greenland. There was no Barneo in those days but there were floating Soviet ice stations not far from the North Pole that were its predecessors.

A tragic learning experience

Our understanding of how the Arctic Ocean currents worked came accidentally out of an exploration tragedy. Between 1879-1881, American George W. De Long tried to reach the North Pole by sailing his ship, the Jeannette, north of the Bering Strait. The Jeannette soon became trapped in the ice and was eventually crushed off the Siberian coast.

De Long's crew tried to haul sleds over the ice to safety in Russia, but 20 men, including De Long, died along the way.

Three years later, to everyone's surprise, wreckage from the Jeannette turned up off the southwest coast of Greenland, near Qaqortoq.

This serendipitous discovery gave the polar explorer Fridtjof Nansen an idea. He built a walnut-shaped ship called the Fram that would ride up when the ice floes squeezed it rather than be crushed. In 1893, nine years after the debris appeared off Greenland, Nansen froze the Fram into the ice off Russia, hoping to drift to the North Pole and then beyond to Greenland.

They didn't quite get there, but Nansen and the Fram survived. And the concept, based on the drift of the Jeannette wreckage, was brilliant.

Multiyear ice

What Greenlanders call Sikorsuit (Big Ice, commonly called multiyear ice in English) from Sikuiuitsoq (the Arctic Ocean) was a regular visitor to Southwest Greenland in the 1960s. It was so solid, it could have floated all the way north to Sisimiut or further.

When these giant rafts of ice floated past in early summer, it was like a seal buffet, a Greenlandic happy hour that left folks stuffed and happy. Polar bears also rode this icy express, which is how they made rare appearances in southern Greenland.

On that memorable day in 1965, locals near the town of Arsuk rubbed their eyes in disbelief. There were huts floating past on the ice. And the huts were intact.

Alfred Jakobsen, a childhood friend of my Inuit husband Ole Jorgen, remembers when some family members were out on a casual seal-and-polar-bear grocery run when they stumbled upon these mysterious huts. Given the scarcity of a Home Depot in Arsuk, they snagged the huts and towed them back to Arsuk. Meanwhile, the multiyear ice continued its northward journey.

Jakobsen’s uncle, Julius, says that he was the one who first saw the huts. He described them as “fine houses on top of a huge ice island.” The huts were intact. According to him, there were five huts, four meters by five meters each.

The huts had an abundance of weather equipment in them and obviously belonged to some drifting polar station. Russian knickknacks inside confirmed that it was almost certainly one of the old Soviet SP (Severny Polyus/North Pole) stations that preceded Barneo.

More huts

Some say that later that summer of '65, a second pair of huts drifted by. The Greenlanders had now snagged seven huts in all. Some speculated that the second huts came from a U.S. drift station called Arlis-2. Arlis-2 floated on a piece of ice shelf that broke off from northern Ellesmere Island. However, the timing doesn't work on this theory, since Arlis-2 was only abandoned in 1965. Its icy platform would have taken at least another year or two to make its way to southern Greenland. But wherever it came from, it was a bounty.

Unfortunately, no photos exist of those repurposed huts, although there is a photo of one of the Arlis-2 structures on its original ice island, below.

Greenlanders, Ole Jorgen says, could teach a masterclass in "reuse, recycle, or else." Nothing goes to waste — not food, not wood, not even a lonesome plastic bottle. Everything’s fair game for a second act, keeping nature spick-and-span for the future generations.These huts were not only useful shelters, they had barrels of oil in them. The local people found those particularly valuable.

Here's hoping the leftovers from Barneo 2024 likewise make it to Greenlandic shores once again. But with Silaannaap allanngoriartornera -- climate change -- the sea ice is thinner and melts faster, so southern Greenland doesn't get those faraway visitors any more. Yet this year, the big ice has already popped by Qaqortoq, so fingers crossed -- maybe, just maybe, reuse is in the air.

An insider's view of what's happening with the famous North Pole station

Next month, for the first time since 2018, tourists will come to the Barneo ice station. From there, they will ski or fly to the North Pole itself. But the experience will be very different this year.

This temporary camp on the sea ice about one degree of latitude from the North Pole has operated for about 25 days in April since the early 1990s. Planes reached Barneo via Longyearbyen, on the Norwegian territory of Svalbard. During this time, a United Nations of adventure tourists have skied, run, parachuted, and sipped champagne at the North Pole. The only things they had in common were a fascination with the polar regions and a lot of money.

Although internationally run for part of its lifetime, most logistics and workers have always come from Russia. The problems began in 2019 when a Ukrainian-owned plane was denied permission to land on Barneo's airstrip because of the growing tensions between Russia and Ukraine. Then came COVID-19, followed by Russia's invasion of Ukraine. Since then, Norway has not permitted Russian planes to land in Longyearbyen. With politics and climate change, many wondered whether Barneo's time had passed.

The Russian route

But surprise, surprise, Barneo is running this year. Although Swiss pharmaceutical billionaire Frederick Paulsen still owns the operation, the Russian presence will be much more noticeable. That is because everyone going to the ice station must travel through Russia and spend several days there. Not exactly a mouthwatering prospect for Westerners these days.

Apart from the political/moral issue, many logistical problems remain. Flights to Russia are limited; you may have to route via Serbia or the Middle East. Most travel insurance will be invalid because Western countries formally advise against travel to Russia. There is typically little or no consular support. Credit and debit cards, even PayPal, won't work in Russia because of sanctions. It's illegal to bring in foreign currency. How do you pay for anything?

Currently, the Barneo company in Switzerland will buy everything within Russia -- flights, hotels, food, and incidentals. Presumably, they will also provide roubles as pocket money.

Two visas needed

Another tricky issue this year: One must secure a multi-entry visa. A single one won’t do the job. The first visa will be used to enter Russia and exit the country at Krasnoyarsk on the way to Khatanga (still in Russia but too small to have a customs office). The second visa is necessary to re-enter Russia on the way back to Krasnoyarsk after the Barneo experience.

So once visitors have officially exited Russia in Krasnoyarsk, they will still spend two days on Russian territory without a valid visa while visiting Khatanga and the refueling/pit stop at Severnaya Zemlya. The same on the way back.

It is also a significantly greater investment of time. The new route to Barneo might shave a few minutes off for those coming from the Far East. For the rest, particularly those jetting in from Europe, it's a marathon, not a sprint. It's a few hours from central Europe to Moscow, then a five-hour flight from Moscow to Krasnoyarsk. It's another five-plus hours from there to Barneo.

The old flight from Longyearbyen to Barneo took just two hours.

In other words, with the Svalbard model, tourists could make a round trip to the North Pole in less than 24 hours. Via Krasnoyarsk-Khatanga, it will take at least three days, weather permitting.

No guns allowed

A last change affects the polar bear protection needed for the adventurers. Polar bears are rare near the North Pole, but they can show up anywhere, anytime. Until now, every group's guide carried a firearm, but Russia has a strict "no guns" policy for foreigners. And lest you think you can simply rent a Kalashnikov like you could rent a firearm in Longyearbyen until recently, think again. Russian law states that no one, not even Russians, can rent guns. Instead, an armed Russian official will accompany each group.

Still interested? There are reportedly four Americans, one Brit, and some Indians and Chinese. In all likelihood, it will be a very quiet year, compared to the hundreds who used to show up here.

Building Barneo

The action begins at the end of March when MI-8 helicopters look for a viable ice floe near the North Pole. Once this elusive piece of frozen real estate is secured, an Ilyushin-76 will fly over the chosen spot. From 600 meters up, it will disgorge bulldozers, fuel, and construction materials by parachute. Then the construction team, strapped to tandem parachutes and possibly questioning their life choices, will leap from a frigid height of 3,000 meters to join the materials on the ground.

Soon, a runway begins to take shape on the world's chilliest construction site. This 1,200m ribbon of ice can welcome a big AN-74 aircraft.

North Pole Marathon

At least one group of Last Degree skiers will leave the Siberian city of Krasnoyarsk in early April. The athletes planning to run a marathon at Barneo are not far behind them. They leave Krasnoyarsk for Khatanga on April 8.

This marathon idea began when Richard Donovan, an Irish ultra-marathoner, ran 42km around the Pole solo in 2002. He subsequently founded what he called the North Pole Marathon. It became the most visible event of the Barneo season. The race didn't take place at the Pole itself for logistical reasons, but the runners did fly out to see it later.

At $16,000 in 2018, it was also the cheapest way to visit the Pole. A lot cheaper, anyway, than the champagne flights, which cost $25,600. (Today, it is $24,000 vs $31,000.)

Still, people from all walks of life came. There were blind and wheelchair participants, cancer patients, wounded soldiers, and many others. I recall the first Aborigine from Australia and a young runner from Greenland who grew up in an orphanage. Roughly 65 people took part every spring.

After the marathon's cancellation in 2019, Donovan assigned the event’s trademark name to a company called Runbuk. Its owners, Oliver Wang and Renna Hu, will operate the 2024 North Pole Marathon for about 20 runners. The race director is Ted Jackson of the UK.

By April 15, a second planeload of Last Degree skiers may or may not materialize. Meanwhile, many would-be visitors are currently scrambling to secure their Russian visas.

Barneo's simple beginnings

How did all this come about? Not just this latest incarnation of Barneo but the idea of Barneo itself?

I’ve crisscrossed the Russian Arctic more times than I care to remember, all the way back to the Soviet era. My experiences in Khatanga during the 1980s were a far cry from the Barneo expeditions of today. Life in Khatanga was anything but easy. The town was a melting pot of indigenous peoples and newcomers, all united by a struggle against the elements.

I’ll never forget one flight from Krasnoyarsk to Khatanga, huddled for warmth under cages of live chickens in the freezing bosom of a cargo plane, only to emerge on the other side covered in…well, let’s just say it wasn’t snow.

Back in those days, the North Pole received zero attention. There was no Barneo and no reason to think about the North Pole. But its precursors had been on the Arctic Ocean ice for decades. These were the floating Soviet research stations, which have been around since 1937. They were called Severny Polyus-1 (North Pole–1), SP-2, all the way up to the latest, SP-41.

Polar science

Picture a group of scientists huddled on a chunk of ice, living in what could generously be called spartan conditions, with an outhouse that became a skating rink come spring. Apart from hard living, sometimes things didn't go as planned. SP-40 met an inglorious end in 2013 when its ice floe broke up unexpectedly, forcing an emergency evacuation of the crew to Severnaya Zemlya.

The collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 turned life in the Arctic on its head. Jobs disappeared, people left, and Khatanga's future was uncertain.

The mammoth man gets an idea

But in the early 1990s, Bernard Buigues, a French explorer and mammoth fossil hunter, credited for discoveries of the Yukagir mammoth and Lyuba, the 42,000-year-old baby mammoth featured in the National Geographic documentary Waking the Baby Mammoth, found time to build the very first Ice Camp Barneo.

Bernard and another French explorer, Christian de Marliave, developed a base in Khatanga to launch high-latitude expeditions.

In that hyper-inflationary era, prices were surreally cheap in Russia if you could pay in Western currency. The cost of building a landing strip was roughly equivalent to two bags of potatoes. The price for skiing the last degree to the North Pole? About $9,000. By today's standards, that sounds almost quaint.

So Bernard Buigues and Christian de Marliave began organizing expeditions out of northern Russia at a modest cost that today would amount to the equivalent of a small yacht. They attracted all sorts, including skydivers leaping from the cavernous belly of an Il-76 cargo plane from 4,000m up. The camp was an exercise in minimalism, erected not out of a desire for profit but from a love of the Arctic.

The story of that first Ice Camp Barneo in the early 1990s is largely forgotten today, partially for political and business reasons and partly because it existed in the pre-internet era.

Changing times

The Latitude 90° and Serpolex Ice Camp Barneo operation, as it was known, chugged along smoothly until 2002, when the tide turned. Buigues and de Marliave, more focused on paleontology and less on money and politics, found themselves edged out by the Russian polar establishment.

Alexander Orlov, a former polar navigator who had successfully navigated his way into entrepreneurship, took the reins. Unlike the French duo, Orlov's interests aligned well with the Russian state. And so, the Khatanga route, once the symbol of the pioneering spirit and adventure on a budget, has come full circle.

The new Barneo

The abrupt cancellation of season 2019 was awkward and painful. COVID-19 killed the 2020 and 2021 seasons. COVID restrictions lingered in 2022, but limitations on Russian planes in European airspace were probably the biggest factor.

In March 2023, just as everyone was gearing up for the grand opening of post-COVID Barneo, the Norwegian aviation authority, Luftfartstilsynet, stepped in. They outlawed the AN-74 flights out of Longyearbyen, supposedly on environmental grounds. They also nixed some helicopter landings for a Tom Cruise flick.

However, the brains behind Barneo had been scrambling for a Plan B for several years. In 2019, Krasnoyarsk governor Aleksandr Uss announced a project to transform Khatanga, a settlement of about 2,500 on the Taymyr Peninsula in Siberia, into a new transit hub to the North Pole.

The Mammoth Inn

At the same time, Frederick Paulsen renovated a Soviet-era hotel in Khatanga into a luxury stopover for the polar-bound elite. Called the Mammoth Inn, its motto is, "Keep Calm and Go Arctic!" whatever that means. The Mammoth Inn publicizes itself as “the only hotel in the world located this close to the North Pole.”

(Alas for truth in advertising, that's not quite correct: Khatanga is located at approximately 72˚N. There are several hotels further north -- in Longyearbyen; Grise Fiord, Canada; Qaanaaq, Greenland, among others.)

Yet the Mammoth Inn is apparently the hottest ticket in town for April. Most rooms are booked solid. You're promised an array of culinary delights, although not mammoth -- at least, not yet. Instead, guests will feast on “traditional venison, northern white fish, wild mushrooms and other native plants…”

And then there's Mamont vodka, a creation of Frederick Paulsen. This vodka, they say, passes through Siberian birch charcoal and gets a cedar nut finish. It is served cold in a bottle shaped like a mammoth's tusk at the hotel bar.

Cultural entertainment in Khatanga includes visits to "airport, seaport, and other cultural sites," a list that manages to be both vague and oddly specific. Then there's the Mammoth Museum, which is worth the visit, because it features some of Bernard Buigues' mammoth finds.

Trial run in 2023

When Norway canceled landings in Longyearbyen in March 2023, the Barneo crew took it in stride. The tourist season may have been canceled, but with both Khatanga and the Mammoth Inn ready, they decided to take special visitors on a trial run to Barneo.

April saw six flights zip between Khatanga and Barneo, ferrying a VIP list of Frederick Paulsen's pals, plus others. There were half a dozen Last Degree skiers, then a second batch of adventurers, and then the crew of nearby Severny Polyus-41. It seemed to go well, and thus work began to organize Barneo's return in 2024.

The North Pole, which is a purely mathematical concept, has been reached by dogsled, dirigible, airplane, nuclear submarine, snowmobile, motorcycle, nuclear icebreaker, ultra-light aircraft, helicopter, parachute, and on skis and snowshoes. Over the centuries, dozens have died trying to get there.

But for all the bragging rights that come with reaching the Pole, there's a sobering reality: You can reach the Pole but you can’t stay on it. It's always drifting south with the ice. Perhaps, in the end, that's what makes the North Pole so alluring: the knowledge that, no matter how hard we try, it always remains beyond our grasp.

An all-female team of Soviet women in fur hats and ski boots carved their path across the Arctic and Antarctic in a quiet rebellion against male dominance in the polar regions. They called themselves Metelitsa, a Russian word for "blizzard."

As the story goes, on June 5, 1976, these women of Metelitsa sprayed Sredny Island’s polar station -- completely dominated by men -- with perfume. At the time, perfume was a scarce luxury in the USSR.

On arctic island after island, this spraying became a signature quirk in their routine. Metelitsa conquered the harshest terrain equipped with bikinis, makeup mirrors, mascara, lipstick, and hand-embroidered handkerchiefs.

This was an unusual approach in the country still busy building Communism, diverting Siberian rivers to irrigate the deserts of Central Asia, and conquering the cosmos. At that time, in the late 1960s and early 1970s, the Soviet Union wanted to dominate nature to showcase its culture's supremacy.

Metelitsa symbolized a struggle of a different kind -- proving that women belonged in the polar regions.

They glided over the ice on rickety wooden skis, equipped not just with sleeping bags and parkas but also AKMs and IZH-56s, to protect themselves from polar bears.

Metelitsa begins

In 1966, Valentina Kuznetsova, a radio engineer and skier, forged the team from former competitive skiers. By their early 30s, they were already part of an older generation of athletes.

As retirement beckoned, Kuznetsova’s friends found a new dream to pursue: skiing across the Antarctic. Their group boasted PhDs, doctors, meteorologists, ex-astronauts, and Olympians.

But men were doubtful. Even Dmitri Shparo, the famous Soviet polar explorer who lived in the same high-rise neighborhood as Kuznetsova and spoke with her often, told me recently, “I could easily imagine a girl skiing to the Pole solo and even unsupported, but a girls’ team? With egos crashing and temperaments colliding? This would be a catfight 24/7. For me, this was just inconceivable.”

By that time Shparo had already successfully skied to the North Pole -- the first group of skiers to get there. To do so, they brazenly defied the Politburo, which had initially denied them permission.

Diplomatic defiance

Kuznetsova and her colleagues sought to defy these preconceptions. They had the skills and training, but they too needed to overcome the resistance of an aging, male-dominated Soviet Politburo.

In the forbidden Soviet Arctic, you needed a special permit to travel. Only the KGB and Communist politicians could dispense this. Thus Metelitsa's quest was twofold: navigating the icy expanses and persuading these unyielding patriarchs to approve their project.

They decided to approach this untraditional idea traditionally -- by playing on both their femininity and their athletic competence.

So, they took selfies to convey their story in images that no male in the Soviet Politburo would ever ignore.

I should perhaps explain: We young Soviet girls were expected to emulate classic femininity out of 1950s Western male dreams, all the while driving tractors and working in space engineering. To revolt against society's norms, we had to use some of these old tools to push forward on our mission. Imagine my grandmother, a field surgeon fresh from the front lines, wearing stilettos while crammed into an overcrowded bus on her way to work. This was perfectly normal in the USSR.

Building up credibility

In 1966, Metelitsa embarked on an ultramarathon, skiing from Moscow to Leningrad, now St. Petersburg — a staggering 766km. Their official aim? Outpace a male nuclear physicists’ team, which had covered the same route in 6.5 days.

The women didn't quite succeed -- they finished in 7.5 days -- but this was enough to earn press attention and mild acclaim among the leadership of Komsomol, the youth wing of the Communist Party.

Soon after that, they tried to organize a ski ultramarathon to Norway, famous for its love of skiing. However, the Soviet Union's invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968 brought that project to a halt.

Navigating unfamiliar corridors of power and diplomacy, the women received permission in 1969 to enter Finland, which had stayed neutral throughout the Cold War. They then skied a formidable 2,600km from Moscow to Tornio, Finland. This became Metelitsa’s longest expedition.

My father, Boris Batsanov, who later became chief of staff for the Soviet Prime Minister, was also a native Finnish speaker and a close friend of Finnish President Urho Kekkonen. He convinced Kekkonen, an ardent skier himself, that these women were an asset for détente. So in Helsinki, Kekkonen greeted them.

Gaining recognition

Now Metelitsa, like their male predecessor Shparo, were sometimes recognized in the streets of Soviet towns and earned a welcome in Communist male rulers’ offices.

But skiing to the South Pole was still a distant dream. Back then, in the late 1960s and early 1970s, no woman could even work in Antarctica.

So the women of Metelitsa had, once again, to prove their worthiness.

Skiing across Severnaya Zemlya and Franz Joseph Land, they crossed the treacherous Vilkitsky Strait. To please the Communist politicians, they carried Lenin's bust with them across the drifting ice. At the same time, they posed near open water like seals, reciting poetry and taking pictures.

They had an idea. Beyond cheesecake photos in bikinis, they concocted a shrewder way to use their bodies -- by serving Soviet science.

They made the acquaintance of Lieutenant General Oleg Gazenko. He was the maestro of the Institute for Biomedical Problems, which dealt with air and space physiology.

Gazenko was behind the two dogs, Belka and Strelka, sent into orbit as a kind of scientific theater.

I interviewed Gazenko in 1983, five years before Metelitsa’s expedition to the Antarctic. He claimed that stray dogs were prime candidates for his research. Like victims of Nazi occupation, hunger, and war, these resilient canines were paragons of survival.

Working for the space program

The Metelitsa women convinced him that their indomitable spirit made them even better candidates for study. So from then on, their secondary job on these grueling expeditions was to collect blood, urine, and other telltale biomarkers vital for the Soviet odyssey into space.

With this backing, Metelitsa finally won permission to go to the Antarctic.

By now, however, they were no longer girls, but seasoned mothers and grandmothers. Valentina Kuznetsova was 51, and her compatriots were likewise older and weathered by time and experience.

Their moment to set foot in Antarctica had come a little late, but it had come and they were ready.

A forbidden world for women

I had a long talk with Valentina Kuznetsova in the fall of 1988, just a few weeks before she left for the Antarctic. We shared our experiences about life on the ice. As a journalist, I specialized in covering the polar regions. Our encounters with polar men were similar. We saw them as heroes, but the men did not reciprocate our admiration.

Before my first season on a drifting Soviet station on the Arctic Ocean, I was asked to “publicly and in writing deny my womanhood.” It meant that I would never be allowed female privacy out there. No separate bathrooms or showers or quarters, nothing. Telegrams went back and forth before I had permission to land, and I agreed to all the conditions.

“We will see you as a man, and if you complain, you will pay the price,” they warned.

I realize it’s hard for younger generations reading this to understand. But for us, born soon after WWII, it was just a part of the deal if we wanted a certain freedom. We took it with as much good humor as we could.

So Valentina Kuznetsova and I laughed about these small, shared inconveniences. For her, dealing with the structures of power was more difficult than dealing with a culture of misogyny. But she needed an alliance with that power to realize her dream of skiing in the Antarctic.

Antarctica at last

In December of 1988, nine members of Metelitsa landed at the first Soviet Antarctic science station, Mirny. They intended to ski to Vostok, another station further inland, 1,420km away. Because the South Pole was a U.S. base, they would not pass that way.

Kuznetsova updated us at the news desk at Pravda via radio, as we covered their progress. They started in very mild weather, 0˚C during the daytime. They skied in long-sleeved wool shirts and did 10-hour shifts with a one-hour lunch stop and short breaks.

After the first 100km, they had climbed to 1,500m. Wind and storms intensified and the nights got much colder: -25˚C. Two “security” vehicles accompanied the team, so admittedly the women were hardly unsupported.

The entire December, they busily planned the New Year's celebration. After 70 years of government-mandated atheism, Christmas was not a big deal, but New Year's was. They had costumes, staged a theater production, and took photo sessions in the tent, which increased the expedition's celebrity.

In mid-January, they reached Komsomolskaya, another Soviet polar station. Here, they learned that the old gents in the Kremlin had been watching them “with precision.”

At the beginning of February, they arrived at Vostok, their final destination. They had skied for 57 days, and survived -52˚C nights and -48°C days. They had succeeded.

On this journey, Valentina's 27-year-old daughter Irina accompanied her as a photographer. Later, Irina wrote a book about this journey and everything that preceded it, called Metelitsa. Almost impossible to find now except maybe in Russia, it was put out by publisher Frederik Paulsen in Moscow.

Finally, the South Pole

Seven years later, in 1996, five years after the collapse of the Soviet Union, six members of the Metelitsa team reached the South Pole. Ironically, Valentina Kuznetsova herself, the founder of Metelitsa, could not join the expedition.

This time, her lack of participation was not because of suspicious males or prickly bureaucracy, but because of a new reality many Russians had not yet learned to deal with: the market economy.

In Soviet times, you didn't have to raise funds, you just needed official permission. With that, all doors opened for you. Now, the women had to pay themselves for air tickets, hotels, everything. This transition from socialism to a market economy was difficult for many.

So four women, including Kuznetsova, reluctantly stayed behind in Chile, and six skied the last two degrees, from 88˚S to the Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station. It took them 13 days.

Now, in late 2023, pretty much no one in modern Russia remembers Metelitsa. Valentina Kuznetsova died in 2010. Her daughter Irina moved to Paris and then to the U.S. I live in the U.S. too, and because of certain opinions of mine, I am no longer welcome in the country where I grew up. Metelitsa still exists as a humanitarian NGO, helping people with disabilities.

Only a few of us old-timers remember those days and look back fondly at those forgotten photos of these pioneering polar women.

Last week, TV personality Justin Fornal couldn't boat through the ice to Canada to begin his swim back to Greenland. Instead, he did a much shorter swim off the Greenland coast. Below, an in-depth look at a well-publicized but failed adventure.

Justin Fornal is an eclectic action-hero who self-identifies as a "cultural detective", "culinary anthropologist", and a "blue-collar explorer". A tireless storyteller and host of the Science Channel’s Unexplained and Unexplored, he loves magic and mysteries, or in his own words, "everything wild and weird". He spends his life trying to go against the grain, or at the very least "trying to get behind some door and see what people are doing".

The Great Arctic Swim

Heading north

Smith Sound

Two great but understated guides

The last migration

Qitdlarssuaq

For some, being first matters

A truncated swim

Thirty-five years ago, during the Cold War, American endurance swimmer and citizen diplomat Lynne Cox swam from the U.S. to the Soviet Union. She did so across the frigid Bering Strait, wearing just a swimsuit, a bathing cap, and goggles. Once she reached the slippery rocks of the Soviet Big Diomede Island, some two hours and six minutes after her departure from Little Diomede Island in the U.S., the Cold War was pronounced over.

Big and Little Diomede

In late July 1987, I flew over the Ural Mountains, which cross Russia from the Arctic Ocean to Central Asia, over Siberia’s endless taiga and tundra, to Chukotka. Underneath, sapphire lakes alternated with mountain ranges and rivers flowing north. It was a familiar landscape and a route that I had traveled many times as a polar correspondent for Pravda.

But this time, I was not sure I would reach my final destination at all. I was flying to a place I have never been before, a forbidden island lying in the middle of the Bering Strait. “Tomorrow Island”, or Ostrov Ratmanova as it was known in the Soviet Union, was closed to most since the early 1920s, some five years after the Communist Revolution.

Once upon a time, this rocky island was the home of a thriving Inupiat community. They moved freely across the strait between Chukotka and Alaska, following the animals. For millennia, the island had a beautiful name, Imaqliq, which means “surrounded by water”. It was facing Inaliq (which in the Inupiaq language means "the one over there", or “the cliff”), now known as Little Diomede. Little Diomede lies three kilometres and one calendar day away, in U.S. territory.

Now Imaqliq/Big Diomede/Ostrov Ratmanova was a top-secret Soviet military base, filled with soldiers, radar, and who knows what else.

Soon after WWII, the proud Inupiat were kicked out of their sacred home on Imaqlik and forcibly relocated to Chukotka’s mainland, into Soviet-style reservations. With the arrival of the Ice Curtain in 1948, much less known to the world than the Berlin Wall, families living across the strait were separated. Travel across the strait came to an end. Brothers could not see their sisters, young children would never meet their grandfathers.

The Californian poet crisis

While approaching Chukotka, I was thinking of a young man, whom I now know well and love. At that time in the Soviet Union, he was more a fairy-tale personage than a real person. In 1965, at the age of 19, he managed to cross the Bering Strait on foot, from Little Diomede to Big Diomede, almost starting WWIII in the process.

His name was Dennis Schmitt. A young Berkley graduate, a poet, mathematician, linguist, philosopher, and musician from California, Dennis Schmitt walked over the frozen strait undetected by Soviet radar. When he reached the shore, locals took him for a ghost; but soon they were so happy to meet an Inuk, a “real human” arriving from the other side. They fought about who would be the lucky one to take the stranger into their home. Dennis Schmidt stayed with his hosts for a couple of days, until the KGB arrested him.

A couple of days later, once news that an American had been captured by the Soviets reached the CIA, military helicopters landed on Little Diomede. In response, Soviet military ships arrived at Big Diomede.

Luckily for Dennis Schmidt, the crisis was resolved diplomatically, and the young poet was sent back to Little Diomede to be thoroughly interrogated by the CIA as a potential Soviet spy.

Enter Lynne Cox

Now, 22 years later, another person from sunny California was about to cross the Strait without a permit. Lynne Cox, a 30-year-old marathon swimmer known for her cold-water abilities, was going to swim from Little Diomede to Big Diomede with a grandiose mission to thaw the Ice Curtain and finish the Cold War.

There were many similarities between the two journeys, but of course, things had changed since 1965. Then, Dennis Schmitt could easily have been shot or vanished into a Siberian GULAG. Certainly, he stayed alive by pure luck. In 1987, with the arrival of Gorbachev’s glasnost and perestroika, Lynne Cox was less likely to receive a bullet.

Cox confronted strong currents, freezing temperatures, sharp reefs, hungry polar bears, and jellyfish. But the hardest obstacle now was not natural. It was ugly politics.

She spent 11 years trying to obtain a permit for her swim across the Bering Strait. Cox wrote to General Secretaries Brezhnev, Chernenko, Andropov, and finally to Gorbachev. There was no response.

The biggest hurdle: bureaucracy

Then came hope. After contacting many U.S. senators, who simply would not believe that this project was either doable or necessary, Alaskan Senator Frank Murkowski was suddenly inspired by Cox’s idea. He contacted the Soviet Ambassador to the U.S., Anatoly Dobrynin, an unorthodox diplomat. He was suddenly inspired too. Dobrynin sent a supportive telegram to Eduard Shevarnadze, the Soviet Minister of Foreign Affairs, and –- most importantly –- to Alexander Yakovlev, the "godfather of glasnost" and the intellectual force behind Mikhail Gorbachev's reforms. Months passed and encouraging messages were exchanged, but the official permit never materialized.

There was no official permit, no real sponsors, and no support, except her family and friends. But Cox decided to go forward no matter what. She used every last penny of her savings to realize her swim.

When she arrived on Little Diomede, locals looked at her with amusement. Most Inupiat, who don’t swim, believe that once you fall through the ice, your chance of survival in the freezing water is slim. To swim a couple of miles from one island to another seemed like madness or suicide.

Could it be done?

Not only the Inupiat thought Cox's swim impossible. Most Soviet scientists and medical doctors studying hypothermia, whom I interviewed before my flight to Big Diomede, agreed: Either Cox’s body or her mind would collapse in the extreme cold. They were arguing which would happen first.

They projected that by the midpoint of her journey, her body temperature would fall to 32°C. Nobody, even those who were praying for peace between the U.S. and the Soviet Union, believed that Cox would make it.

I reached Big Diomede Island two days before her swim. At night, a small gathering of adventurous Soviet reporters and athletes toasted the occasion, but almost everyone shared the same doubts.

One athlete familiar with Cox’s previous swims across the English Channel said that, "She may make it because she is more like a seal than a woman." According to this gentleman, an "abnormal amount of subcutaneous fat creates a sort of a wetsuit, or a seal skin, and thus makes the body resistant to the extreme cold."

A Soviet colonel present at the table suggested that Cox might cover her body with a layer of walrus fat (quite an insane idea for swimming a strait filled with polar bears). Others speculated that Cox would use some secret American warming batteries. The crowd argued where these batteries would be hidden.

But despite the disbelief, the frigid air of Big Diomede was filled with excitement and hope. Everyone knew that something grand was about to happen.

And then, exactly 24 hours before the start, the official permit finally arrived from the Kremlin.

Tomorrow Island

The next morning, we were standing on the rocky shore of Big Diomede, or Tomorrow Island. Reporters, athletes, special services, military staff, diplomats, and politicians all peered into the fog.

When the permit arrived only 24 hours before the swim, rumor was that the Inupiat guides commissioned to lead Cox across the Strait were so happy that they had a night-long celebration. For the first time in 48 years, they would see some of their relatives.

When they woke up, the morning sun had disappeared. A thick fog called naternaaq (low fog, as opposed to kipisimaq, high fog) fell onto the water. The umiaqs (boats made out of walrus skin) lacked navigation equipment. They only had an old rusty compass. The other problem was that none of the young guides had ever been to Big Diomede themselves.

With 400m of visibility, Cox was afraid that she would miss the island, which was rather small despite its name. She also felt the temperature drop to 5˚C. Her arms were turning gray, “the color of a cadaver”, in her own words.

But stroke after stroke, she crossed the International Date Line. In less than an hour and a half, from August 6 on Little Diomede Island, she arrived into tomorrow, August 7.

An extra 800m

The fog was getting denser, and Big Diomede was nowhere to be seen. Suddenly, Cox heard a boat engine somewhere nearby. The Soviet support vessel, sent to lead the way to Big Diomede, had discovered her and her team.

A Soviet translator on the boat informed Cox that a big welcoming party of journalists and others was waiting for her on the shore, 800m further than Cox had planned. She had to make a tough decision on the spot: to get out of the water on the closest shore or swim an extra 800m to meet the people.

She decided to do the 800m extra. “I felt like if I touched a rock instead of someone’s hand, what have I done? Nothing,” she recalled later. The last 800m were the hardest.

When we finally saw Lynne in the water, we started jumping, screaming, crying, and hugging each other. Finally, after almost 50 years, the border was open again.

Lynne was so exhausted that she could not pull herself up onto the sharp rocks, and a few military guys had to help her. Then it was time for the doctors to take her away from us for some time.

Reverberations from the swim

Later that year, President Gorbachev traveled to Washington to sign the Intermediate Range Nuclear Forces treaty. President Reagan raised a glass to toast the swimmer. And then Mikhail Gorbachev said something unimaginable for the Soviet leader:

“Last summer, it took one brave American by the name of Lynne Cox just two hours to swim from one of our countries to the other. We saw on television how sincere and friendly the meeting was between our people and the Americans when she stepped onto the Soviet shore. She proved by her courage how close to each other our peoples live.”

After Lynne Cox’s swim, the indigenous people from Alaska and Chukotka were finally granted the right to see each other. The Ice Curtain had started to melt.

That's how Lynne Cox became the biggest citizen diplomat of our times.

Reunion

Two weeks ago, I met Lynne again, 35 years later after our first meeting on Big Diomede. We both cried. I told Lynne that her swim in 1987 changed lives of many people, including my own. On that day, I understood that one can overcome extraordinary obstacles by taking risks, and that the human body and mind, so vulnerable, can perform miracles, if there is a will.

Today, everything that Lynne built in the Bering Strait in 1987 has fallen apart.

We are in the fog again.

Lawrence Khlinovski Rockhill, one of the old-timers who helped to rebuild the sundered connection between American and Russian indigenous peoples in late 1980s, asked me on Facebook after reading my post about Lynne Cox:

“Where are all the Ice Curtain Melters when we need them now? We did it before, and yes, we can do it again!”

In the last week, haunting images of polar bears peering out from abandoned cabins in the Russian Arctic have gone viral. ExplorersWeb spoke to Dmitry Kokh, the tech entrepreneur-turned-photographer who took the images.

The 41-year old Kokh runs a successful tech company in Moscow. The popularity of his photos has surprised even him. He has had to take a vacation from his day job, because of the endless requests to buy prints of the bears.

Enjoys the company of animals

Kokh is an introvert by nature. He seems to feel more comfortable around animals than people. He tends to spend most of his time traveling to the wildest, least accessible places.

Last August, he and a friend traveled 2,000km on a small ice-class sailing yacht to Russia’s Wrangel Island, known as a polar bear maternity ward. Kokh hoped to capture the white bears up close.

The two adventurers slowly made their way along the coast, past humpback whales, sea lions, seals, and birds, across a constantly shifting ice-and-water puzzle. They stopped in deserted bays, saw plenty of brown bears, and went scuba diving in the freezing waters of the Chukchi Sea. As you can see from his website, Kokh is also a serious underwater photographer.

Eventually, the sea ice thickened. It was early fall, the best time of year to travel up there because the ice is at its minimum, and they were not expecting this obstacle.

One day, a storm caught them in the middle of the Chukchi Sea and forced them to take refuge behind a small island named Kolyuchin. Today, Kolyuchin is entirely abandoned, but it was a thriving community when I first visited it 36 years ago as Pravda’s polar reporter.

The story of Kolyuchin Island

Kolyuchin’s name tells its history. Kulusik means a “field of sea ice” in the Chaplino Eskimo dialect, while Kuvluch’in means “round” in Chukchi. Indeed, from above, Kolyuchin looks almost round, and since ice and snow cover it for nine months a year, it is almost always white.

For millennia, Kolyuchin has been a hunting ground both for the Chukchi and the Yupik, who shared the island. Some lived all year round in a small settlement, while others migrated here in the summer to hunt walruses, seals, and polar bears, and to collect berries, mushrooms, and eggs.

Then, in 1934, at the height of Soviet colonization of the Arctic, a polar meteorological station was built on the island. This was not an easy ordeal for those assigned there. Logistics were horrible, and there was no fresh water. By then, the indigenous name of the island had become russified into Kolyuchin, which literally means “a prickly place”.

The indigenous elders who grew up on the island told me another story of Kolyuchin’s name. According to their version, Keglusin means a lonely maritime giant, or rather, a lonely adult walrus who had lost its mother too early, in infancy. It grew up to be mean and aggressive, attacking everyone.

The island was apt for such a legend, because of its humongous walrus aggregations. They gather in the thousands on the rocky beaches.

Kolyuchin abandoned

Time stopped on Kolyuchin in 1992, soon after the collapse of the Soviet Union. Because of lack of funding, the polar station, like many others in the Arctic, shut down. Today, Kolyuchin is wilderness with a few derelict buildings. Occasionally, locals come here by boat or dogsled from nearby Nutepelmen, 14km away, to hunt.

'We noticed a movement in the window'

“There was a lot of wind, rain and fog," said Kokh when we spoke over the phone. "As we were waiting for the weather, we noticed a movement in the window of the abandoned station. This was strange. I grabbed the binoculars, and to my amusement, I saw a polar bear in the house. And then another one, and another. We could not land, so I flew my drone.”

“One never knows what and when nature presents you with. I just know that the best gifts come when we least expect it. One has to be ready.”

And ready he was. As a tech guy, Kokh has played with drones for a long time. None of those on the market were good enough for what he wanted, so he decided to build his own. He used a regular DJI Mavic 2 and modified it with low-noise propellers, which he ordered on AliExpress from China. Kokh knew that the model's original noisy propellers would scare the animals off.

He also developed a special tactic, similar to the one used by indigenous polar bear hunters. He approached them slowly, zigzagging and avoiding a direct advance. This worked well on Kolyuchin: The bears just took the drone for a low-flying gull and went about their business. You can see his successful approach in how relaxed the bears are in the photos.

Important not to disturb the animals

“When my photos went viral, I did not want to say too much about how I made them," says Kokh. "But later, as most people came to believe that I simply walked with the bears, I thought that sent the wrong message. A human should not walk with the bears, for the good of both. So I decided to make it clear how exactly I produced these images.

“Drones are easy to operate, but one has to be extremely cautious not to disturb the animals, and this takes a lot of knowledge of psychology, as well as tech skills.”

Most arctic cruise ships, for example, don't allow its passengers to fly drones, because they can't be relied upon to have Kokh's sensitivity or knowledge to avoid disturbing the animals.

Polar bears have become a symbol of climate change. Photographers often picture them on dwindling pieces of sea ice amid rising temperatures. The images convey a message of grief at the prospect of their disappearance.

Kokh’s photos portray the bears in a happier light. They seem to be thriving in the remnants of human civilization. It may be an illusion, because the bears live among rusted oil drums, debris, and dilapidated huts. But the overall impression gives a message of thriving life, overcoming disintegration, a mood of hope.

Why do the bears go into cabins?

This morning, I called a few biologists who have studied polar bears all their lives. None could explain why polar bears would inhabit a human house.

But Anatoly Kochnev, a polar bear specialist living in Anadyr, Chukotka, who had spent 18 seasons on Kolyuchin, had his own hypothesis.

According to Kochnev, polar bears on Kolyuchin are quite familiar with humans. They have been hunted here for centuries, and even now occasionally local residents shoot an animal or two, although it is against the law. So bears use the polar station as a refuge. Once a boat shows on the horizon, with all its familiar sounds, they retreat into the building.

Shortly before Kokh arrived in the area, a cruise ship did turn up nearby. They drove along the coast in Zodiacs, photographing the shore bears through long lenses.

Kochnev has managed to create Russia's first database logging the conflicts between polar bears and humans. He recalls that in his first five years of work in the Arctic, he saw polar bears only twice. In those days, the bears lived on the sea ice, far from settlements. Today, polar bears are often forced into settlements because the summer sea ice has vanished.

A future truce?

But even their increasing presence near people may be workable. Kochnev points out that polar bears, unlike brown bears, are not territorial. Near Cape Schmidt, there is a Chukchi settlement named Ryrkaypiy. Every fall, dozens of polar bears gather on the beach, just two kilometres away from the village, waiting for new ice to form, as in Churchill, Manitoba.

Over the years, humans and animals have somehow learned to respect each other’s privacy. Maybe there is a way for people and bears elsewhere to become good neighbors in the Arctic.

There is a legend in Greenland, which I first heard 10 years ago in Qaanaaq. This is how it goes. In the old days, polar bears used to be people. After a while, they would go back to their homes, take off their heavy fur coats, sit down around the table, and have some tea. It was a time when humans and animals lived in harmony, and the circle of life was unbroken.

Even though most people have never heard of this legend, the hopeful, unifying message of Dmitry Kokh’s images somehow resonate within us.

Visual artist Galya Morrell has lived and traveled in the Arctic for over 30 years. Under the stage name ColdArtist, Galya explores the limits of the body and the possibilities of the mind, working in a rare genre of visual synthetic performance on the drifting sea ice. Together with Greenlandic polar explorer and actor, Ole Jorgen Hammeken, Galya has founded many cultural initiatives focused on the circumpolar regions.

Hans Henrik was an unusual polar explorer. He went on five dramatic arctic expeditions and saved the lives of many of polar explorers, but he was always homesick.

Henrik was a family guy who loved his kids and wife so much that he refused to go on expeditions without them. So they accompanied him. His youngest son, Charlie Polaris, was born on board Charles Francis Hall's ship, the Polaris, just before it ran aground. The newborn baby then participated in a 2,900km, six-month drift on a disintegrating ice floe.

Geese were the messengers

Two months ago in our present era, in Qeqertarsuaq on Disko Island, we were following a flock of Canada geese for no apparent reason. The geese were not supposed to be here at this time of the year. By mid-September, they should have all been en route to Canada. But this summer was eternal, and here they were, devouring the late blueberries and getting fatter. Instead of flying away, they were leading us somewhere.

They took us to the local cemetery, to some old graves. There were no berries here. They walked across old stones and suddenly took off. Making a circle above our heads, they then vanished, leaving us alone at the old grave.

That was a sign. Geese were the messengers, as they say in Greenland. The geese brought us to Suersaq, a.k.a. Hans Henrik, the great Inuit polar explorer.

Two islands have been named after Hans Henrik, and a stamp in Greenland honors his memory. But his posters do not adorn the walls of aspiring polar explorers, and his Inughuit name, Suersaq, is known only to aficionados.

Some say that Suersaq did not take Arctic expeditions seriously, that he saw the efforts to map the Arctic as a substitution for a big polar bear hunt. Indeed, Suersaq had no ambitions to be “the first” in the race to the North Pole. Like Ootaah and other Inuit explorers, he did not join these extreme expeditions with endurance records in mind. It was life as usual, though his employers called it "an expedition".

But it was his practical skills, endless adaptability, and unbreakable spirit that helped save qualified Europeans and Americans. They came to the Arctic with a mission but instead went into survival mode when Sila, the weather, had a final say.

A life of freedom

Suersaq never thought of himself as a pioneer or a hero. He did not attribute what he did daily to courage or endurance. Instead, he was vulnerable and emotional, he felt threatened among foreigners, but he was who he was.

He deserted the first expedition he took part in because that life got too boring. Instead, he fled with his fellow Inughuit to live an unstructured life. The Inughuit were free, while the expeditioners were not.

During his flight, he hunted polar bears and found a girl, Mequ, the love of his life. That was much more fun than establishing some official and -- from his point of view -- irrelevant record, like reaching the 82nd parallel by dogsled. Besides, he knew that his Inughuit buddies had trod this ground previously on many hunts and none of them saw it as a special accomplishment.

First Inuit man to write a book of exploration

Yet Suersaq was an educated man. He wrote a book about his arctic adventures, the first Inuk to have done so. Originally composed in 1877, it has often been reprinted. Memoirs of Hans Hendrik, The Arctic Traveler gives details of the Kane, Hayes, Hall, and Nares expeditions, as well as an account of August Sonntag's death. Suersaq wrote it in Kalaalissut, the Greenland language, and Hinrich Rink, the colonial director for Greenland, translated it into Danish and English and published it.

Born in the southern settlement of Fiskenæsset (today Qeqetarsuatsiaat), some 100km south of Godthåb (today Nuuk), as Hans Hendrik, Suersaq was raised in the Moravian faith and attended a Moravian school, where he learned to write and read.

His first expedition

At age 18, Suersaq was already an excellent subsistence hunter and great kayaker. Not surprisingly, the American explorer Elisha Kent Kane recruited him. Kane was commander of the Second Grinnell Expedition, bound for the island’s northern end to search for John Franklin's lost expedition.

Examining the fate of past American misadventures in Northwest Greenland, Kane knew that the only way to survive in these latitudes was to live Inuit-style. He was looking for someone who could be a perfect Inuit: a dogsled driver, a kayaker, a hunter, and an interpreter.

Kane says of Suersaq: "I obtained an Eskimo hunter at Fiskernaes, one Hans Christian (known elsewhere as Hans Hendrik), a boy of eighteen, an expert with the kayak and javelin. After Hans had given me a touch of his quality by spearing a bird on the wing, I engaged him."

Suersaq accepted the offer since he had to help his elderly parents.

After a rapid start, the expedition got stuck near Cape Alexander, in the Thule District, for two long winters. It was in the winter of 1854 when Suersaq became famous and a much-desired guide among American explorers. When four men disappeared on the ice, he found their sled track and brought a rescue party to the frozen men. When expedition members started to starve and developed scurvy, he was able to get food. Once again, he had saved the party.

Free spirit

Suersaq was skillful but he was a free spirit. The expedition routine was too boring for him. He was also frightened by the white men, whom he thought were going to harm him. Something might have been lost in translation, but this is how he felt according to his book. So when he met the local Inughuit of far northern Greenland (a different culture than the more southerly one he came from), he fell in love with their lifestyle. They were truly independent. The Americans were not. So he left with the Inughuit.

It was a brave move. At that time, the West Greenlanders saw these northern denizens as dangerous outcasts. There were superstitions, but Suersaq managed to overcome them. Yet as a devoted Christian, he worried for the Inughuits' souls.

A time of gifts

Suersaq received two very important gifts during his escapade. First was the beautiful Mequ, who became his wife and had four children with him. The second was his name, Suersaq. According to Nuka Muller, one of the most prominent Eskimologists of our time, Suersaq is an Inughuit name that means “the saved" or "the healed one”. It was bestowed only by Inughuit angaqqoks (shamans), which for us means this: Hans Henrik had to work hard to deserve it.

Despite his desertion, Kane so highly valued Suersaq that he named an island north of Etah after him.

When a member of Kane’s expedition, Isaac Israel Hayes, started a new expedition toward the North Pole in 1860, he invited Suersaq to join him. Suersaq agreed under one condition: He would not leave without his wife and son. This was not an easy decision for Hayes, but he agreed to let them join the expedition.

Suersaq provided food and shelter for Hayes and his men, while Mequ fished, cooked, sewed, and kept the seal-oil lamp burning. She turned out to be a valuable addition to the expedition too, and the couple’s fame increased.

Hayes' expedition failed to reach the North Pole. It also lost a man, the second in the command, a German astronomer August Sonntag. Sonntag fell through the ice during a sledge journey with Hans. Though Suersaq saved Sonntag from the freezing water, almost dying himself, he could not save his life. Sonntag died during the night from hypothermia. Suersaq was on the verge of death too, but he managed to reach the Etah Inughuit and find refuge.

The arrival of the Polaris

After the departure of Hayes, Suersaq spent 10 years in Upernavik working for the Royal Greenland Trade Company. Then one day, another ship with a mission to discover the North Pole arrived. This time it was Charlie Francis Hall, the leader of USS Polaris, who asked Suersaq to join his expedition. Suersaq had the same answer as before: He would not travel without Mequ and the kids. This time, there were three of them. Hall accepted.

The Polaris managed to go further than any ship before her, but then, in the northern part of Nares Strait, Hall suddenly fell ill. He died in Thank God Harbor two weeks later, apparently from poisoning. Shortly before his death, Hall named another island after Suersaq. This time it was Turtupaluk, which means a “kidney” because it looks like a kidney, a rocky island in Nares Strait. Hall named it Hans Island.

A barren, steep-sided, one-kilometre-wide bit of land, Hans Island has become modestly famous in recent years, because both Canada and Denmark claim ownership of it.

Six months on an ice floe