A while back, I was gazing at a bronze plaque pegged into a diabase cliff on South Quadyuk Island in the Kitikmeot region of Nunavut. The plaque contained these words: IN MEMORY OF THOMAS GEORGE STREET OF OTTAWA AGE 23 YEARS WHO DIED GOING TO THE AID OF HIS FRIEND JULY 12, 1912.

Street did not die going to the aid of his friend. Quite the contrary. But let’s go back a bit in time. Born in 1885, Street had a demanding, quick-to-anger father who condemned his almost every act. Not surprisingly, he grew up with a deep respect for authority. At the same time, he tried to escape authority by canoeing and hiking in Ontario’s backcountry. Rumor has it that he could carry a load of 200 pounds on his back while walking on muskeg, no problem.

In 1911, Street was working as a general utility man for a surveying party in Smith’s Landing, Alberta, when an American named Harry Radford appeared on the scene. Radford claimed to be an explorer, indeed a highly acclaimed one, although he had done most of his exploring in upstate New York’s Adirondack Mountains. Hence his nickname, “Adirondack Harry.”

The proposal

Might Street be interested in a 5,000-kilometer, two-year Barren Ground expedition? Radford wondered. Of course, he, Radford, would get the lion’s share of food if their supply ran short, and he’d also have exclusive rights to publishing the story of the expedition. Street immediately agreed to accompany Radford even though his coworkers in Smith’s Landing thought he was “plumb crazy” to do so, and the local Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) Corporal Mellor declared, “The gentleman is utterly helpless.” He was referring to Radford, not Street.

The Yukon bard Robert Service encountered the two men on a Hudson’s Bay Company steamship on the Slave River en route to Fort Resolution. Radford, he wrote in his memoir Ploughman of the Moon, “was pushed by the idea of exalting himself in his own eyes if not in the eyes of the public,” while Street was both “waterwise and woodwise.” John Hornby and George Douglas also happened to be on the ship. Had these individuals accompanied Radford and Street, their expedition probably wouldn’t have come to such an unpleasant end.

Radford's temper

At Fort Resolution, a nun gave Street a bottle of Holy Water to protect their expedition from storms…actual storms rather than Radford’s periodic temper tantrums. The two men paddled their 19-foot Peterborough canoe east to Artillery Lake, then along the Hanbury and Thelon Rivers and north to Chesterfield Inlet, with Street doing all of the portaging. They hoped to reach Bathurst Inlet before the onset of winter but got only as far as Schultz Lake. Here, they lodged in the multi-chambered igloo of the chief, an Inuk named Akulak.

Unlike Radford, Street spent a good deal of time hanging out with the local Inuit. Posted from Chesterfield Inlet, his letters to his family suggest a genuine interest in Inuit culture. Here are two snippets from them:

“Eskimo children never quarrel or cry, and their parents never reprove or punish them. In fact, they [the Eskimos] are the most contented people you can imagine.”

“The reason Akulak gave me for not wanting to die was that he wouldn’t be able to eat anymore. Especially not eat any more deer [caribou] tongues.”

In the spring, Radford hired a guide, an Inuk named Bosun, for the sledging trip to Bathurst Inlet, but Bosun bowed out when Radford refused to provide for his family during his absence. An angry Radford reached for his rifle and threatened to shoot the fellow if he didn’t become the trip’s guide. “Go ahead and shoot,” Bosun said, and Radford put down his rifle. A portentous moment.

Somber news

Finally, Akulak agreed to guide them to Bathurst Inlet, and they made the

six week trip without incident. Upon arriving at their destination in early May,

Radford immediately began mapping what he called “the last strip remaining unexplored on the continental coast of North America.” He didn’t get very far into mapping that strip, however, because on June 11, 1913, Akulak arrived at the Hudson Bay Company trading post in Chesterfield Inlet and told H.H. Hall, the post’s

manager, that Radford and Street had been murdered by the Bathurst Inlet Inuit.

Nowadays the RCMP could fly to Bathurst Inlet to investigate the murders, but not in those days. An overland patrol led by Inspector Francis French underwent all sorts of obstacles and arrived at Bathurst Inlet five years after the murders occurred. Upon their arrival, members of the patrol raised their hands high above their heads, the traditional friendly greeting among northern Inuit.

After taking depositions from ten men and women, French decided not to prosecute the culprits, since native people were not subject to the same laws as other Canadians. But he told the local Inuit that if they killed any more white men, the killer/killers “would be taken away and never be allowed to return.” This was the worst of all possible threats since most Inuit would rather be executed than taken away from their Arctic homeland.

How the murders went down

Lay missionary and explorer W.H.B. “Billy” Hoare had visited Bathurst Inlet before Inspector French and described the murders in a letter to Street’s family. He wrote that an Inuk named Kaniak had agreed to guide Radford and Street, but Kaniak changed his mind when his wife fell on the ice, and he needed to look after her. Radford went berserk and tried repeatedly to dunk Kaniak in the icy sea. Before he could drown Katiak, another Inuk, Hulalak, stabbed Radford three times in the small of the back with sharp, double-edged knife, then cut his throat so he would die quickly.

“Street tried to stop Radford,” Hoare wrote in his letter, “and since he had no luck in doing this, he went to his sled and started off a little with it. Hulalak and a man named Amelgeanik ran up, caught him, and stabbed him because they were afraid the white people would come and finish them [the Inuit] all off if he got away and told the authorities what happened to Radford. Both bodies were thrown into the sea. The Eskimos all say Street was a good man.”

Rasmussen's testimony

In Across Arctic America, Rasmussen wrote that he’d “lived for a month

with the two murderers…and found them both kindly, helpful, and affectionate;

thoroughly good fellows all around.” Amelgeanik himself was deeply upset that he’d killed Street, so deeply upset that he later gave Hoare his three finest white fox pelts and told him to give them to Street’s family, which Hoare did. I asked Street’s half-sister Eleanor Hart (nee Street) Golden whether she remembered seeing the fox pelts around the house. “Yes,” she told me. “We kept them for a while, but they went bad, and we had to throw them away.”

Let’s return to the plaque. As you now know, Street was going away from his friend, not to his aid, and likewise that so-called friend was a father figure morphed into a crazed expedition leader. A pity Street didn’t get very far from Radford, for if he did, he might have become a well-known Arctic explorer, or perhaps more likely, a guide for well-known Arctic explorers. Dare I say that such guides are often better explorers than the explorers themselves?

Thanks to Sheila Thompson, who provided me with copies of letters from her father W.H.B. Hoare, and to Eleanor Hart Golden, who gave me copies of the letters her half-brother George sent to his family.

A while back, I was looking for relics from the 1913 Karluk Expedition on Wrangel Island. Certain members of that expedition spent the better part of a year on this remote Siberian island after their ship was crushed by ice, and Captain Bob Bartlett played Chopin’s “Funeral March” on his Victrola to accompany its sinking. Those who survived their lengthy stay on Wrangel were rescued by the Canadian schooner King and Winge in September of the following year.

Near Cape Litke, I happened to see not a tattered glove from one of the Karluk’s castaways, but an arctic woolly bear caterpillar (Gynaephora groenlandica) basking on a small rock and looking like it didn’t have a care in the world. This isn’t the same species as the temperate woolly bear (Pyrrharctia isabella), which is commonly thought to predict winter weather — the thicker its brown stripes, the warmer the winter will be. Rather, it was an endemic High Arctic species that doesn’t predict winter weather so much as triumph over it.

I kneeled to get a closer look at this tan-brown, thumb-sized creature. The temperature was slightly below freezing, and like me, it was wearing a parka. Or I should say it was covered with the equivalent of a parka — thick bristly hairs called setae that provide it with external insulation and help it absorb as well as retain heat.

A clever sunbather

Speaking of heat retention, the caterpillar can raise its body temperature 42˚C (75˚F) above the air simply by basking in the sun. It does this basking much of the time when it’s not feeding or searching for food. No high-intensity workouts for it! As the summer progresses, it becomes increasingly chubby, since chubbiness is a good survival morphology in the Arctic.

Quite a few members of the Karluk Expedition suffered from hypothermia

during their time on Wrangel. If an arctic woolly bear caterpillar could talk, it

might have said “Try to synthesize some glycerol, guys,” to these shivering men. Glycerol is a compound that the caterpillar manufactures to keep its body cavity from freezing.

Several members of the Karluk Expedition also ended up with Hypervitaminosis A from eating polar bear liver. As a result, they suffered from fatigue and nausea, along with bits of their skin peeling off. If the caterpillar had been able to talk, it might have said “Eat arctic willow leaves,” to these distressed individuals. For the buds and leaves of this creeping shrub (Salix arctica) are its primary food from June until mid-July, after which the buds are gone, and the leaves turn yellow and lack nutrients.

Voluntary hypothermia

In late summer, the caterpillar heads down to a sheltered site close to the permafrost and creates a silken hibernaculum as its winter home. Then it undergoes what Olga Kukal, the world’s leading G. groenlandica expert, calls “voluntary hypothermia.” Frozen solid like a popsicle, it has no worries except for the occasional parasitoid wasp or fly that overwinters as a larva inside it and, while doing so, feeds on it.

Come spring, the caterpillar thaws itself out and again begins to eat arctic willow buds and leaves, or if none of these are around, on purple saxifrage leaves. By contrast, I suspect that if Sir John Franklin’s doubtless frozen body is ever found and thawed out, the result would be a foul-smelling heap of carrion incapable of eating a ship’s biscuit or even an Arctic willow leaf.

The first person to spend any time studying arctic woolly bears was James Ross (1800-1862), the naturalist on his uncle Sir John Ross’s 1829 Arctic expedition. Best known for his discovery of the Magnetic North Pole, James Ross collected a number of frozen woolly bears on Fury Island in the Gulf of Boothia. He brought them into the expedition’s warm cabin, where (he wrote) “every one of them returned to life and continued walking about…”

Survives for 14 winters

Ross probably didn’t realize that the caterpillar freezes and thaws each

year for a remarkable 14 years. And whatever the lowest temperature might have been on his uncle’s expedition, it wouldn’t have been nearly as low as the temperature the woolly bear is able to tolerate. What would that temperature be, you might wonder? At least -71˚C (-95˚F)!

After 14 years, the caterpillar has gotten enough resources to pupate and become an arctic woolly bear moth. Compared to a luna moth or a monarch butterfly, this grayish-black moth isn’t a particularly attractive lepidopteran. But what matters to it is not beauty but sex — it must find a mate and lay eggs in a short time because its life span is no more than two weeks. That the moth, unlike the caterpillar, isn’t frost-proof makes it all the more eager to find a mate.

Back to the caterpillar. You would expect it to be present in Inuit folklore, given its seemingly folklorish behavior. Might there be a story about a woman who marries a G. groenlandica because it’s much braver than any man she knows? I never heard such a story, nor did I hear any lore about arctic woolly bear quklurriat (caterpillars) during my meetings with Inuit.

Actually, I did hear one tidbit of lore. In Upernavik, West Greenland, I once met an Inuk who told me his father wore a neck amulet with an arctic woolly bear encased in it. Since the caterpillar can survive extremely frigid conditions, his father figured this amulet might help him do so, too. And it worked, the fellow said with a grin. For shortly after he created the amulet, the government moved his father from a poorly heated turf hut to a well-heated home for elders.

In the end, I didn’t find a single relic from the Karluk Expedition. But I did find something perhaps more interesting than a relic — a furry little creature far better adapted to the cold than almost any other insect, not to mention most members of my own species.

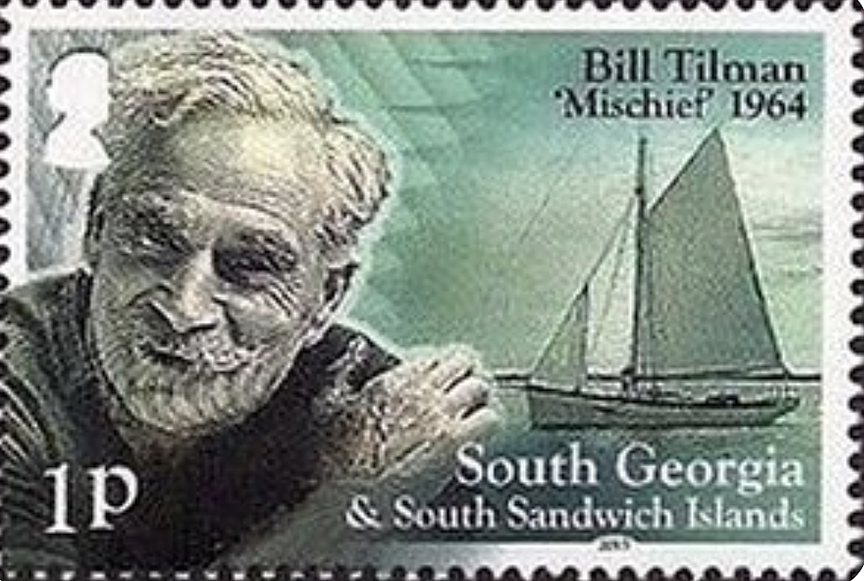

As a dedicated technophobe, I’ve always felt a certain kinship with the English explorer H.W. Tilman (1898-1977), who would have thrown a GPS into the trash, assuming he ever had one. On his mountaineering expeditions, he engaged in alpine-style climbing and refused to bring any oxygen equipment with him, while in his seafaring trips, his boats carried no technical devices other than a compass, a sextant, and a short-wave radio. Nor did those boats have engines, since he preferred to be under sail. “Radar is a superstition,” he once wrote.

In 1986, I was in the village of Angmagssalik (now Tasiilaq), East Greenland, and I happened to ask a local Danish shipbuilder if he’d ever met Tilman, who’d visited these parts several times in his pilot cutter Mischief.

“Funny you should ask me that,” the fellow said. “I repaired the Mischief in 1973 when it was struck by ice floes. While I was doing my repairs, Tilman climbed that mountain over there every day” — here he pointed to a steep icy mountain — “to examine the ice conditions in the fiord. Or that’s what he told me. I actually think he climbed the mountain just for the hell of it. Because he was that sort of guy. By the way, he must have been 75 years old at the time.”

Just walk out the door

Tilman was indeed “that sort of guy.” A would-be explorer once asked him how he could get on an expedition, and “Bill” (as his acquaintances called him) replied, “Put on a good pair of boots and walk out the door.” He himself lit out for the territory whenever possible. For him, that territory included the battlefields of war (he served valiantly in World War I), the wilds of Africa (he bicycled east to west cross the continent — a first), the Himalaya (he made the first ascent of Nanda Devi in 1936), Patagonia (he sailed through the notoriously difficult Strait of Magellan), or some remote part of the Arctic.

So how did he travel? By foot, by boat, or by bicycle. “Only a man in the devil of a hurry would fly to his mountain, foregoing the lingering pleasure and mounting excitement of a slow, arduous approach,” he once wrote. He seemed never to be in the devil of a hurry himself, which makes him quite different from a number of better-known explorers.

Tabasco sauce essential

Like many an English explorer, Tilman was something of an eccentric. Or maybe he was just a man who marched to the beat of his own drummer. You can experience his idiosyncratic march by reading any of his 15 travel books, particularly the Mischief ones.

In doing so, you’ll learn that he thought Tabasco sauce was an essential item to be brought on an expedition, since anything, even lifeboat biscuits (i.e., hardtack), could be made edible with a few drops of it. You’ll also learn that he advertised his Mischief expeditions with these words: “Hand wanted for long voyage in small boat. No pay, no prospects, not much pleasure.” Believe it or not, he got plenty of enthusiastic replies.

Since I’m an arctic hand myself, I have a particular interest in Tilman’s arctic expeditions, all of which took place in his later years and featured the Mischief as well as another pilot cutter called the Sea Breeze. Among the reasons he liked the Arctic was that he didn’t have to submit to any authority other than himself.

“No bother, no police, no customs, no immigration or health officials to harry us,” he wrote about it.

He could have added something like “only a wondrous natural world” to end this description. At 3,000 feet on a mountain in Greenland, he found a yellow poppy and was utterly enchanted!

A hard trek at age 65

Bylot Island is rugged island off the northwest coast of Baffin Island in the Canadian Arctic. Taking a boat from the Inuit village of Pond Inlet, I once tried to hike across it, but I didn’t get very far before my energy gave out. Not so Tilman! At age 65, he was considerably older than I was, but he made a first crossing of the island in 15 days. That crossing included negotiating his way over an ice col that was 5,000 feet above sea level. “The hardest 50 miles I have ever done,” he said with a grin.

Even more remote than Bylot is Jan Mayen, a Norway-owned island to the east of Greenland. Rising up from it is Beerenberg, a 7,470 foot mountain that’s the northernmost active volcano in the world. I climbed it in three days and ended up being blanketed by volcano ash. One of my companions who didn’t make the climb claimed not to recognize me when I returned to our base camp.

Tilman himself was eager to climb Beerenberg, but before he could do so, the Mischief got stuck on an offshore rock. A goodly percentage of the boat’s supplies were lost, but the item he most lamented the loss of was his pipe. The Norwegians who manned the island’s weather station tried to save the Mischief, but to no avail. Tilman felt like he’d witnessed the death of a dear friend. Even so, he found another friend in the Sea Breeze, and the following year he stopped at Jan Mayen en route to Scoresbysund in East Greenland. “Mr. Tilman, I presume?” one of the Norwegians said to him.

Hunger for adventure grew stronger

As he aged, his desire for adventure seemed to grow stronger. He wanted to spend his 80th birthday in the Arctic, but since that birthday was in February, Antarctica seemed like a more appropriate destination. Thus he sailed south in a gaff-rigged cutter called En Avant with a young explorer named Simon Richardson. In Rio de Janeiro, he sent letters to several of his friends in England. Then — silence. The En Avant vanished without a trace somewhere in the South Atlantic. Tilman was doubtless pleased to have breathed his last in this fashion rather than in a hospital or an old folks home.

My thanks to librarian Mary Sears for providing me with some obscure facts about Tilman’s life.

Once upon a time, Arctic explorers were so devoted to their goals, whether the attainment of the North Pole, the traverse of the Northwest Passage, or discovering an unknown continent, that they seem like they were suffering from OCD. Not so John Hornby (1880-1927), assuming he can be called an explorer. What he most wanted to do was meet the rough integrity of the Arctic — specifically, Canada’s Barren Lands — with a rough integrity of his own. If that meant hardship or potential starvation, so what?

Born to the realm of English social privilege, Hornby grew up attending lawn parties and going on fox hunts, then attended Harrow School. He soon rejected this background with all his heart and soul. What could be more removed from his family’s capacious mansion Parkfields than an abandoned wolf’s den or a freezing esker, inside both of which he overwintered? And what could be less upper-crust than using a stick instead of toilet tissue when he was traveling? Such actions almost seem like attempts to reduce English pluck to a Monty Python-ish level.

Hornby cut his boreal teeth with such capable northern hands as Cosmo Melville, Guy Blanchet, and George Douglas. Then he began traveling either alone or with hard-bitten Barren Land trappers such as Darcy Arden, whose son told me that “Jack [John] could go farther on a diet of snow and air than anyone else could go on food.”

Wintered inside an esker

Darcy Arden Jr. also told me this story: “My father found Jack digging in the snow near the east arm of Great Slave Lake. He seemed pretty well gone. He told Dad, ‘I’m looking for a wolf skull that I threw out a while back.’ He was going to cook down that skull since he had nothing else to eat. Dad gave him some food and probably saved his life.”

Enter Captain James Critchell-Bullock, with whom Hornby overwintered in 1923 inside the aforementioned esker near Artillery Lake in the Barren Lands. Bullock had been a cameraman in various campaigns in the Middle East during World War I, and he’d brought along $3,000 worth of photographic equipment so he could film this expedition.

Like Queen Victoria, Hornby was not amused. He felt a person should experience life directly rather than with a device like a camera. As a young boy, Darcy Arden Jr. told me that he heard the two of them arguing in a canoe at the outset of their trip. Hornby wanted Bullock to discard his photographic gadgetry, and Bullock refused to do so.

“I was traveling with my dad,” Darcy Jr. said, “and we got so tired of hearing them argue that we paddled away.”

Lost footage

Bullock did shoot some footage of the trip, but he reputedly disposed of it as excess baggage on an island in the Hanbury River during his and Hornby's arduous retreat on the Hanbury and Thelon Rivers to Baker Lake. In 1996, I happened to be writing up the Hornby/Bullock expedition, and I got in touch with Bullock’s daughter Claudia in England and asked her about the lost footage.

“Funny you should bring this up,” she said. “A month or so ago, we opened an old trunk in the attic, and what should we find inside it but my father’s film. Shall I send it to you?” Not surprisingly, I told her “Yes!”

I was a bit surprised by the film, however. There were no dramatic moments, such as when Hornby and Bullock arrive in Baker Lake at the end of their expedition, and a local Inuk wonders where the blazes this scrawny, disheveled pair has come from.

Instead, there were only brief scenes and stills. A dying wolf turns around in a circle and falls to the ground. One of Hornby’s dogs chases a muskox out of the frame and then reappears, being chased by the same muskox. Hornby himself appears, then dodges out of the frame. The camera focuses on him again, and he dodges out of the frame again. It’s obvious that he didn’t want the sort of attention that most explorers would have craved.

Last expedition

Accompanied by two greenhorns, his 18-year-old first cousin Edgar Chris-

tian and an explorer wannabe named Harold Adlard, Hornby embarked on his

final Barren Lands expedition in 1926. The destination would be an apparent oasis on the Thelon River that he’d seen on his expedition with Bullock.

In typical Hornby fashion, the trio traveled in such a desultory fashion that they missed the annual caribou migration southward. Likewise, they didn’t bring along a shotgun for killing small game. Thus, Hornby was playing Russian roulette with his life as well as two other lives. But he wouldn’t have used the phrase Russian roulette. Instead, he would have said something like “I can tough out any situation.”

Bullock made the following prescient statement in his diary: “I fancy Jack is destined to give his life to the Canadian hinterlands that he loves so well.” On July 21, 1928, a group of geologists found a rough-hewn cabin on the shores of the Thelon River. Outside the cabin were two bodies, Hornby and Adlard’s. Inside, they found a blanket, and when they unrolled it, Edgar Christian’s skull tumbled out.

Edgar Christian's diary

They reported their gruesome discovery to the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, who traveled to the cabin and discovered Christian’s own diary in the stove. The diary, later published as Unflinching, describes the deaths by starvation of each of the three men. In its pages, Hornby emerges as a heroic individual who did his best to save the lives of the other two, even as his own was wasting away.

By now, you’re probably thinking that John Hornby wasn’t so much an explorer as he was simply an oddball. It might be more appropriate to think of him as an environmentalist. For after his expedition with Bullock, he gave Canada’s Department of the Interior a 16-page, single-spaced document requesting that immediate measures by taken to protect the Upper Thelon region from human exploitation.

This document planted the seed for what is now North America’s largest protected wilderness area, the 90,000 square kilometer Thelon Game Sanctuary. In my opinion, Hornby’s act of planting was considerably more important than, say, planting a flag at the North Pole.

Thanks to Mary Sears at Harvard’s MCZ Library for excavating some obscure tidbits of information about Hornby for me.

Contrary to what you might think, quite a few fungi can be found in the Far North. In Svalbard, 1,200 species have been documented, while somewhere between 600 and 700 species have been reported from Greenland.

In 2007, I was doing a survey of fungi in the vicinity of Kuujjuaq, Nunavik. There happened to be a large number of species there, too. At one point, a local Inuk who was helping me collect specimens brought me a mushroom-shaped species. I already had the species on my list, but as I gave it back to him, I happened to mention that it was a decent edible. The fellow shook his head. Mushrooms, he said, are tunitinging (caribou food). And if they’re caribou food, he added, they’re definitely not human food.

Myths about mushrooms

Different Inuit groups have different words and phrases to indicate their aversion to eating mushrooms. East Greenlanders call mushrooms qivittoq sopa, on the assumption that the cannibalistic monster called a qivittoq uses their frequent slime as soap. Of course, this makes them flagrantly inedible.

The Inuit of the Central Canadian Arctic believe mushrooms are the anaq (shit) of shooting stars. Across the night sky, a shooting star will hurtle in the late summer or fall, leaving a trail of detritus behind it, and in the next day or two, there are mushrooms on the tundra.

“You wouldn’t want to invite a friend to dinner, telling him you’re serving the anaq of a shooting star, would you?” an Inuk in Baker Lake, Nunavut, once told me.

In Alaska, the Inupiaq call mushrooms argaignag (that which makes your hands fall off), so you shouldn’t touch, much less pick them. If you do, you should blow immediately on your hand or it will soon fall off. At the very least, it will become rancid.

The Yupik believe mushrooms are the ears of evil spirits, and they call them chertovysuhi ushi (devil’s ears). Thus if you say something personal or confidential if you’re anywhere near one of them, you’ll be sorry…and you’ll be even sorrier if you decide to eat them.

Medicinal uses

Here I should mention that the Inuit do have non-culinary uses for certain fungi which aren’t mushroom-shaped. For example, they use the spores of a puffball as a styptic. If someone jabs their hand with a knife or a harpoon, they might take a puffball and squeeze the spores into the wound. Chitosan, a component in fungal cell walls, will bond with red blood cells and form a clot that will quickly stop the bleeding. Also, those spores have splendid antibiotic properties, like many other fungi (think penicillin, which is derived from the fungus Penicillium chrysogenum), so there’s very little chance the wound will end up with a bacterial infection.

You might think that a belief that all mushrooms are repulsive is a way of protecting one’s fellow humans from eating poisonous ones and kicking the proverbial bucket. But I haven’t encountered any potentially fatal species in the Arctic. Yes, there are several species that can cause gastroenterological distress, such as the Fly Agaric (Amanita muscaria) and the Sickener (Russula emetica). But could such mushrooms have created a phobia that stretches all the way from Alaska to East Greenland? Would they have inspired an Inuk I once met in Rankin Inlet to say “I’d rather eat bear scat?”

Probably not.

Why the bad reputation?

So from whence comes this fear of an organism that’s considerably less fearful than, for instance, a mother polar bear protecting her cubs? With respect to its origin, Canadian ethnobotanist Nancy Turner suggests that the Pleistocene ancestors of the Inuit may have brought this fear with them across the Bering Strait from northeastern Siberia. And with respect to the phobia itself, a doctor friend of mine thinks many Inuit may get (or may have gotten) some sort of idiosyncratic reaction after they’ve eaten mushrooms — something similar to lactose intolerance.

I’d like to offer my own conjecture, which is as follows:

A person needs plenty of calories to survive as a hunter-gatherer in the Arctic. While mushrooms are full of protein, they don’t have much in the way of calories (aka, fat). If a person happens to be starving, and he or she eats something with little or no calories, their hunger will be accelerated. That’s because a starving person’s body metabolizes its own calories, and eating something rich in protein speeds up rather than slows down that metabolic process. The commonly used phrase “rabbit starvation” describes the effect of eating exclusively lean meat. “Mushroom starvation” might be considered an equivalent phrase, although I can’t imagine many Inuit suffering from it.

And yet as the hunter-gatherer lifestyle is slowly but surely dying out in the Arctic, the Inuit phobia about mushrooms would appear to be dying out, too. Recently, I saw several piles of scaber stalk (Leccinum sp.) mushrooms for sale in a store in Cambridge Bay, Nunavut. “Very popular here,” the store’s clerk said. I wasn’t really surprised to hear him utter these words, since, well, as time passes, taboos tend to pass along with it.

“He was our Rembrandt and maybe our Picasso, too,” an Inuit schoolteacher in Tasiilaq, East Greenland, once told me. He was referring to Karale Andreassen, who, in addition to being an artist, was also an ethnographer, a catechist, a writer, a teacher, and a film actor. In other words, a veritable Renaissance man, although one hardly known outside Greenland.

Karale was born in 1890 in the vicinity of Angmagssalik. His birth name was Kavkajik, which means “Snow Bunting” in Greenlandic, but that name was changed to the more pronounceable Karale by Danish officials after he was baptized in 1899. His father was the well-known angakok (shaman) Mitsivarniannga, whose specialty was creating tupilaks.

Initially, these “hell animals,” as explorer-writer Peter Freuchen called them, were compendiums of animal bones and parts of a child’s corpse, but they became grotesque bone, ivory, and driftwood carvings in the early 20th century. Yet whatever it might be made from, a tupilak would come alive by sucking its creator’s genitals (Mitsivarniannga means “Suck Me”), after which it would go after its victim. Usually, that victim would end up with his or her entrails yanked out, but if the victim was strong enough, the tupilak would be sent back to yank the entrails out of its creator.

An illustrator of the supernatural

Given his father’s area of expertise, it’s not surprising that Karale — after traveling to Godthaab (now Nuuk) and studying art — became an illustrator of tupilaks. His pen or pencil drawings of these surreal creatures are often rather surreal themselves. They also have a darkly comic aspect not unlike certain Greenlandic folktales. Imagine a grinning human skull atop the skeleton of a bird advancing toward an oblivious hunter. Or imagine a Godzilla-sized polar bear rising from the sea and attacking a kayaker.

Karale made more or less realistic drawings as well. Here’s an example: two parents bent over and grieving beside their deceased son’s burial cairn. Not a single Christian principle occurs in any of his drawings, even though Karale became a catechist (he studied Christianity as well as art in Godthaab) and taught such principles to his fellow East Greenlanders.

Perhaps because he was a Christian, Karale ended up being more devoted than he would otherwise have been to preserving the past traditions of his culture. Thus he became a go-to font of knowledge for ethnographers such as William Thalbitzer and especially Knud Rasmussen, whose Fourth and Seventh Thule Expeditions he participated in. In fact, his drawings as well as some of the ethnographic lore he collected are in Rasmussen’s write-ups of these expeditions.

Like Rasmussen himself, Karale may have embellished some of his material. Consider his legend Kunuk, Kagssagsuk, Ultlivatsiardlo, which appears in Rasmussen’s Posthumous Notes on East Greenland Legends and Myths. This novella-length tale wanders hither and yon in describing the adventures of the three Inuit featured in the title and ends with Kagssagsuk’s formerly difficult son saying to a group of young men: “Amuse yourselves and pet my wife a little…”

Helps pioneer ethologist Niko Tinbergen

But not only ethnographers sought out Karale. As part of the International Polar Year (1932-33), the young Dutch scientist Niko Tinbergen came to East Greenland and lived with him in Kungmiut. Karale became his guest’s guru, teaching him how to paddle a kayak and how to hunt seals as well as telling him about the social relations of his sled dogs.

Tinbergen soon began studying the competitive interactions of these canines himself. He also studied the territoriality and demeanor of snow buntings — could he have been inspired to do this after Karale told him his birth name? Back in Holland, Tinbergen became a well-known animal behaviorist, and in 1973 he shared a Nobel Prize with two other celebrated animal behaviorists, Karl von Frisch and Konrad Lorenz. If he hadn’t been tutored by Karale, he might not have gotten this prestigious award!

Shortly after Tinbergen left Greenland, Knud Rasmussen asked Karale to be his collaborator on a feature film about pre-contact life in East Greenland. Entitled Palos Brudefaerd (The Wedding of Palo), this film turned out to be more or less an amalgam of stories and legends both men had collected. Karale and Rasmussen supervised the shooting, and the German documentary film-maker Friedrich Dalsheim, famed for Insel der Damonen (Island of Demons) and Menschen Im Busch (People in the Bush), served as the film’s director.

As it happens, Karale acted in the film as well. The hero Palo has been stabbed by the villain Samo during a piseq (song duel), and Karale plays the angakok who, by chanting, hissing, and sipping Palo’s blood, brings him back to life. In doing this, he was probably emulating one of his father’s shamanic acts.

The last chapter

Once the film was finished, Rasmussen took Karale to Denmark with him so that he, Karale, could do a voice over in sync with the lip movements of the film’s actors. Since he’d eaten tainted seal meat in Greenland, Rasmussen was already ill, and he died of botulism compounded by influenza and pneumonia on December 21, 1933. Karale himself died on February 22, 1934 of tuberculosis shortly after he completed the synchronization of the film. Somehow it seems fitting that these two like-minded individuals should die in the same place within a very short time of each other.

I was wandering around Labrador’s small, relatively flat Eskimo Island with my boatman, an Inuk from the nearby village of Rigolet named Jimmy. The island, an amalgam of black spruce, birch trees, and naked granitic rock, had a number of old Inuit sod houses, all excavated by archaeologists. At one point, I noticed some burial cairns, one of which Jimmy said had once contained the remains of Caubvick (pre-anglicized name: Qavvik), the young Inuit woman for whom the tallest mountain in Labrador was named.

Let’s now go back in time. Along with four other Inuit from the Hamilton Inlet area, the 17-year-old Caubvick was brought to England from Labrador in October 1772 by the entrepreneur George Cartwright on the assumption that, upon seeing how civilized his country was, the “Esquimaux Indians,” as he called them, would trade with no other nation. The visitors spent much of their time in London, a place that wasn’t particularly congenial to them. “Too much noise! Too much smoke! Too many people!” one of them said.

Caubvick herself became the proverbial belle of the ball. She danced before King George III, and her portrait was painted by several well-known English artists. Cartwright’s sister Catharine was captivated by the young woman, describing her as “an ornament to her sex.” Remarkably nondiscriminatory words about an indigenous person for this period in human history!

Catches smallpox

But Caubvick wouldn’t remain this sort of ornament for very long, since she caught the reigning virus of the day, smallpox, just before Cartwright’s ship was scheduled to head back to Labrador. One by one, the other Inuit died of smallpox, but Caubvick’s case seemed somewhat less severe, and she ended up on the ship. Cartwright thought the virus resided in her pus-matted hair, so — in spite of her vehement protests — he sheared off almost all of it.

The local Inuit eagerly greeted the ship when it arrived. But when Cartwright informed them that only Caubvick had survived the trip, and when they saw her bald head and the red pustules all over her face, they went berserk. One of her cousins grabbed a rock and smashed her own head with it, apparently knocking out one of her eyes. Caubvick’s brother flung a spear at Cartwright’s boat, but this did no more damage to the boat than if (in Jimmy’s words) “he had spat on it.”

“If this is civilization, my people thought it’s better to remain savages,” Jimmy told me.

He went on to say that his people didn’t remain savages because almost none of them remained alive. For they had no resistance to the highly contagious virus Caubvick brought with her from England, nor did they know anything about social distancing, a measure that existed long before our planet’s recent debilitating virus.

Empty graves

But back to the burial cairns. All the ones I saw seemed to be empty, having either been looted or excavated by archaeologists. Empty, I should say, of human remains. But most of them were filled with algae, lichens, and mosses since the inside of the cairns were miniature ecosystems with plenty of humidity. In one of the cairns, I saw a solitary femur with a green Lecanora lichen growing on it. What a splendid color to accompany one’s journey to oblivion, I thought.

I now asked Jimmy how the remains he’d mentioned earlier could have been identified as Caubvick’s. Because the skeleton had a King George Medal around its neck, he told me, then said the skeleton in question had once been “the prettiest girl in all of Labrador.” Such sad words! Upon hearing them, I could almost feel tears brimming in my eyes.

In the early 1920s, Hudson’s Bay Company trader George Cleveland would sometimes take out his false teeth and put them back in again, Igloolik elder Rosie Iqallijuq told me in 1995. She said the Inuit at Repulse Bay had never seen false teeth before, and they thought Cleveland might be some sort of angakok (shaman). If they didn’t trade with him, he might put a curse on them. As it happened, he gave them his genes rather than a curse. Stay tuned…

George Gibbs Cleveland was born in 1871 on the Cape Cod island of Martha’s Vineyard in the twilight of the whaling days. At that time, illicit methods were sometimes used to acquire a whaleboat’s crew. Cleveland himself was shanghaied as a young man, and he ended up spending seventeen months in Hudson Bay.

Shanghaied

Shortly after he got back, he was shanghaied again, and he ended up in Hudson Bay again. Later he wrote that he found the whole shanghaiing process, which often included being clubbed on the head, “great fun.” This might seem a bit masochistic, but perhaps not, since that process took him to his favorite locale in all the world — the Arctic.

Cleveland spent almost all of his adult life as a trader in northwestern Hudson Bay, where he became known as Sakkuartirungnaq, which means “The Harpooner” in Inuktitut. Not only does that word refer to his past life as a whaler, but it also refers to his eagerness to acquire Inuit “wives.”

He never seemed to have fewer than three of them. And just as he appreciated Inuit women, he also appreciated the fact that the local Inuit did not adhere to any religion.

“They are faithful to their own fine moral code,” he wrote in an article for a New England newspaper. Compare this with missionaries commonly flying into a rage if an Inuk even hinted that a seal or caribou had a soul, as did a human being.

Meeting with Knud Rasmussen

In December 1921, the celebrated Fifth Thule Expedition arrived in Repulse Bay. Eager to explore more of the Arctic than simply the Hudson Bay area, Cleveland told ethnographer Knud Rasmussen, the expedition’s leader, that “the Eskimos on the West Coast speak a language that I am the only white man to know…so it is imperative that I accompany you.”

This was obviously a fiction since he could hardly speak the local dialect of Inuktitut, much less any West Coast dialect. Not surprisingly, Rasmussen turned down his offer.

A member of the Fifth Thule expedition, explorer-author Peter Freuchen, found in Captain Cleveland (chief traders were called captains in those days) a kindred larger-than-life personality, and he wrote about him in several of his books.

We learn that Cleveland kept lemmings as pets and that they once escaped from their cage and took refuge in Freuchen’s capacious beard. We also learn of a bust-up Christmas dinner, which should have been 10 courses, but in order to fortify himself, Cleveland drank so much alcohol that the dinner ended up being only a single course, an over-cooked caribou steak.

Freuchen wasn’t averse to embellishing a good story to make it a better

one, but at least one thing he wrote about Cleveland would seem to be true. In his autobiography Vagrant Viking, he said that “all the little Eskimos [in Repulse Bay] had Captain Cleveland’s nose, which was larger than any nose in the Arctic.”

When he blew his nose, it sounded like thunder

Rosie Iqallijuq also told me that Cleveland’s nose was extremely large, and his loud blowing of it sounded like thunder. Might this also have had a shamanic effect on the local Inuit? she wondered.

Cleveland was hardly the only Arctic trader to sire children with Inuit women. Duncan Pryde, who worked for the Hudson’s Bay Company in the 1950s and 1960s, declared that “every community should have a little Pryde.”

Cleveland’s offspring were much more numerous than Pryde’s, however. According to historian Kenn Harper, roughly 20 percent of the Inuit in Nunavut today share Cleveland’s genes.

Chris Baer, an expert on Cleveland from Martha’s Vineyard, believes the number is closer to three percent. In a newspaper article, Baer wrote that Cleveland’s descendants in Nunavut include heavy metal musicians, CBC radio hosts, government officials, website designers, social workers, and soapstone carvers. Some of these descendants, he said, have recently been matching their DNA with the DNA of their Martha’s Vineyard cousins.

During the winter of 1924-1925, Cleveland became quite sick. He was dogsledded south from Repulse Bay to Churchill. From there he traveled to Winnipeg, where doctors told him he needed immediate medical attention.

Since he marched only to the beat of his own drummer, Cleveland ignored this advice and headed down to New England. On August 25, 1925, he died in a Boston hospital of liver cancer, a predictable disease for a man who would often say, “Liquor is my favorite drink, any kind, and any brand.”

Let me conclude by quoting Rosie Iqallijuq again. “Captain Cleveland, he was such an interesting man,” she told me.

After an expedition to Siberia’s Wrangel Island, I took a boat to the mainland village of Inchoun, and from there I expected to fly to the town of Anadyr and then home. But when I arrived, I was told that the plane had some unspecified mechanical problem. Would I be stuck in these parts for hours, perhaps even days? I wondered.

I wandered around Inchoun, which means “Cut Off Nose Tip” in Chukchi. This name is derived from profile of an adjacent cliff, which seems to have part of its edge cut off. The village’s small schoolhouse was modeled after a seal or walrus hunter’s overturned boat.

Speaking of walrus hunters, I encountered one at the village dock. He was a robust fellow and, in fact, his name Omryn actually means “robust fellow” in Chukchi. We started talking in a mixture of pidgin Russian and pidgin English. I said I was an American. “Don’t be insulted,” he told me, “but I like walruses much more than I like Americans.” I told him that I did too.

Just above the dock, an ancient-looking woman was sitting on a bench and doing some knitting. Suddenly a drunk teenager staggered over to her and began yelling in Chukchi. Whatever he said, it seemed to upset the old lady.

“Pridurok!” Omryn hissed. Which means “asshole” in Russian. He told me that the boy was asking the old woman how many centuries it’d been since she’d slept with a man. He also told her that she looked like she was dead, but if she was still alive, could she give him some rubles for a bottle of vodka?

After saying pridurok again, Omryn told me the following story:

Once upon a time, a young Chukchi man was making fun of an old woman. He said he would prefer sleeping with one of his reindeer to sleeping with her. At least the reindeer still had some flesh on its body. As it happened, the old woman was a shaman, and these insults made her quite angry. She began chanting, all the while gazing angrily at the man.

Omryn interrupted his story as two ATVs roared past us. Then he continued. As the old woman was chanting, the man’s penis burst through his trousers, then began growing larger and still larger. The fellow ran down to his canoe, climbed into it, and began paddling away. But his penis had become so large by now that it caused the canoe to capsize, and the man drowned.

“When I was a young boy, I heard that story from my grandfather,” Omryn observed. “He told it to me as a warning not to make fun of elders.”

I looked over at the drunken teenager, who was still harassing the old woman. “The boy’s penis doesn’t seem to be getting any larger,” I said.

“Not yet,” my companion replied.

At this point, one of my plane’s flight crew came down to the dock and told me that the mechanical problem had been solved, so I should immediately head over to the runway. Before I left, I shook Omryn’s hand and thanked him for his storytelling. Or perhaps his truth-telling.

In 1992, I hopped a bush plane and flew from Rankin Inlet to Ferguson Lake, Keewatin (now Nunavut). After I climbed out of the plane, black flies began mobbing my every available pore, then drinking from my fountain. “Welcome to Ferguson Lake!” my Inuit guide Willie said with a wry grin on his face.

Here’s the good news. As soon as I set out with Willie to explore the local tundra, a meek wind became a strong one, and the black flies departed for parts unknown. I should mention that this section of Keewatin was itself a part unknown until 1894, when explorer Joseph Burr Tyrrell discovered Ferguson Lake during his Geological Survey of Canada Expedition. Speaking of geology, a mining company has recently announced a plan to do exploratory drilling for nickel, copper, and platinum in the vicinity of Ferguson Lake. Not good news at all…at least not for the environment.

I had traveled here not only to escape the throes of civilization, but also to document the local fungi. After an hour or so, I saw several small, black, pear-shaped Sporormiella fruiting bodies sticking out of some muskox dung. Fossilized Sporomiella spores have been found in the fossilized dung of mammoths, and as I gazed at this not particularly charismatic species, I felt like I was in the presence of something primordial.

Coincidentally, I saw a muskox standing perhaps 150 feet away from us, and not far from the muskox was an Inuit burial cairn. That critter is always hanging out here, Willie told me. The reason why, according to elders, is that the cairn’s occupant was an angakok (shaman) who commonly transformed himself into a muskox. Willie warned me not to take a photo of either the muskox or the cairn, lest I anger the angakok.

“What would happen if I did anger him?” I inquired.

“I might have to build a burial cairn for you” was the answer.

This area would be a really nice final resting place, I thought, but since I had no wish to undergo a premature burial, I kept my camera in my rucksack.

The wind suddenly died down and out came the black flies again. “God help us!” I exclaimed. But my request didn’t receive an answer. Perhaps the Supreme Being’s bailiwick didn’t include this remote section of the Arctic, or maybe he had no wish to engage in battle with rival lords (aka black flies).

I asked Willie what the local Inuit did to ward off black flies and mosquitoes. We don’t wash ourselves, he said, and then they can’t detect us because our skins are covered with dirt and grime. Unfortunately, I’d taken a shower that morning before I got on the plane, so I now had no choice but to anoint my skin with citronella oil.

Near the lake, I noticed a relatively large, brownish-white mushroom half-buried in sphagnum moss. Maybe a Russula or Lactarius species? I thought. On closer inspection, it turned out not to be a mushroom, but a very old coffee mug. Could this mug be an artifact from the Tyrrell Expedition? I wondered. Maybe Robert Monro Ferguson, an avid sportsman and a member of that expedition (the lake is named after him), had seen a caribou and left the mug behind in his haste to run off and shoot it? But Ferguson was a Scotsman, so he probably drank tea rather than coffee. Another mystery in the history of exploration.

It was early evening, and a plague of mosquitoes now replaced the black flies. After Willie and I planned tomorrow’s outing, I walked toward my tent. The silence of the surrounding tundra was so complete that I could hear the mosquitoes calling my name.

In 1991, I gave a talk about my ethnographic fieldwork with the Labrador Innu in the library of Na-Bolom (House of the Jaguar) in San Cristobal de las Casas, Chiapas, Mexico. The facility’s 90-year-old owner, environmental activist and photographer Gertrude “Trudy” Blom, introduced me to the dozen or so individuals in the audience. After my talk, I sat down for the Q&A, and Trudy said, “You are sitting in B. Traven’s favorite chair…”

Upon hearing this remark, I felt honored. “Did you ever meet Señor Traven?” I asked her.

“No,” she replied, “but my husband Frans knew him well.” Frans Blom, who died in 1963, was a Danish explorer and archaeologist who is sometimes called “the Indiana Jones of Chiapas.” He seems to have known everyone who ventured into these parts with exploration on their mind.

The reader of this essay may be familiar with Traven as the author of (among other books) The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, which director John Huston made into a movie starring Humphrey Bogart. The reader may also know that Traven’s identity was such a mystery that he was thought to be an illegitimate son of Kaiser Wilhelm II, author Jack London, a convict from Devil’s Island, the Bavarian anarchist Ret Marut, a German jack-of-all-trades named Otto Max Fiege, or even Frans Blom himself. But the reader may not know that, regardless of his identity, Traven was an explorer and ethnographer.

In May 1926, he joined a scientific expedition to the state of Chiapas as a Norwegian named Traven Torsvan. Shortly after the expedition set out, he decided to travel on his own, accompanied by a lone native guide…a not unusual decision by a man who was devoted to keeping his identity a secret. The expedition was sponsored by the Mexican government, and for a dyed-in-the-wool anarchist like Traven, anything supported by a government would have been an offense against humanity — perhaps another reason for his early departure from the other expeditioners.

Chiapas provided Traven with habitats beyond any he had ever imagined. In his untranslated book Land des Fruhlings (Land of Springtime), he describes his travels in those habitats as follows:

“I have ridden through jungles, waded through swamps, swam across rivers, climbed steep cliffs, crept into unexplored caves, and offered myself to thirsty vampires.”

One gets the impression that he thrived on discomfort, even on adversity. Otherwise, he would doubtless have driven away the thirsty vampires rather than offered himself to them!

Traven journeyed to remote parts of Chiapas several more times in the late 1920s. In these trips, he visited traditional Mayan peoples such as the Lacandones and Tzitzol in order to collect lore from them. He used this lore not in academic papers, for he was no more an academic than he was Ambrose Bierce (another of his putative identities), but in his fiction. He also put into his fiction, especially the so-called Jungle Novels, accounts of the abuses suffered by his Mayan informants at the hands of wealthy plantation owners. Those rich honchos weren’t happy with what Traven wrote about them and apparently threatened revenge, which may be the reason he didn’t return to Chiapas after 1930.

My own expedition to Chiapas ran into a snag, but not because of irate landowners. I wanted to query elders in San Juan Chamula about whether or not magic mushrooms were part of their culture. Just outside that village, two young men, probably Guatemalan refugees, emerged from the bush and demanded my money. As one of them was brandishing a handgun and the other a numchuck, I had no choice but to give them all the cash in my wallet. They also took my library card, probably on the assumption that it was a credit card.

That evening, I consoled myself by visiting the library at Na-Bolom and reading not B. Traven but a few stories by P.G. Wodehouse. I did sit in Traven’s favorite chair, however.

Once upon an earlier time, I was doing ethnographic work in the village of Angmagssalik (now Tasiilaq), East Greenland. As a respite from sitting down and recording the stories of elders, I went with a local Inuk for a hike on the tundra just outside the village. As a further respite, I began looking for mushrooms while we were hiking.

Contrary to what you might think, Greenland boasts a plethora of mushrooms, indeed five times as many mushroom species as it has species of vascular plants. We soon saw an example of this plethora — a colorful carpet of red Russulas, yellowish Amanitas, and purple Cortinarius more or less at our feet.

I reached down to pick a mushroom I didn’t recognize and peer at it through my hand lens. “Naamik!” shouted my companion, then he added: “Do not touch.” There was a worried look on his face.

Might the fellow have been displaying a prejudice against mushrooms commonly found among certain Inuit groups? An example: the Inuit in the Central Canadian Arctic believe mushrooms are the anaq (shit) of shooting stars. In the fall, a shooting star will race across the night sky, leaving a trail of detritus behind it, and the following morning mushrooms have appeared on the ground. Obviously, those mushrooms are the anaq of the shooting stars, and no less obviously, they are flagrantly inedible.

“Do not touch because it’s anaq?” I asked my guide, pointing to the mushroom in question.

He shook his head. “Qivittoq sopa,” he explained.

From the time I’d spent in Greenland, I knew about qivittut. They were monstrous beings who lived in the mountains and regarded us humans as prime edibles. A qivittoq will fly into a village, grab a person, and immediately scarf down that person. Or it’ll fly its prey back to its mountain home for later consumption. Several houses in Angmagssalik were unoccupied at the time of my visit because a qivittoq had flown into them in search of human cuisine. The houses were empty because they were now thought to be qivittoq property.

But qivittoq sopa? “Paasinnagilara,” I declared to my companion. Which means “I don’t get it.” After all, the word for mushroom in West Greenland is pupik or, if the person is a speaker of Danish, svamp.

Before I offer you my companion’s explanation, I should mention that many Arctic mushrooms — indeed, many mushrooms in temperate regions as well — have a coating of slime on them. This slime is a sort of anti-freeze that helps them survive in cold weather. The mushroom I was getting ready to pick was probably a Hygrocybe, otherwise known as a waxy cap. ‘Waxy' is a nice word for ‘slimy.’

Now for the explanation. Qivittut smell bad, really bad, my companion told me, and they need to wash themselves lest they give away their presence to us. They do this washing with the slime from mushrooms, lathering themselves all over with it. You wouldn’t want to touch, much less eat something that a qivittoq bathes with, would you? What’s more, if a qivittoq finds out you’re collecting its cleansing agent, more than likely it’ll come calling, and you’ll be lucky if you escape with your life.

Greenlanders often use Danish if they want to utter some sort of insult. I now decided to do so as well. “Ga ad helvede til, din fjola!” I said to the mushroom I’d been getting read to pick. Which means “Go to hell, you bugger!”

My companion grinned. Whether this was because he thought my remark was amusing or whether he too wanted the mushroom to go to hell, I have no idea.

For the rest of the hike, I neither touched nor picked any mushrooms. Tundra blueberries, yes; but not a single mushroom. For I wanted to show my respect for my companion’s culture. What’s more, I wanted to preserve a conviction that goes back, far back, in time.

Near the village of Northwest River, Labrador, I once rented a cabin from a woman named Katharine whom men of a certain age called “Gasoline”. They would say, “Good morning, Gasoline” to her, or “Want some caribou haunch, Gasoline?” I later found out that she’d acquired this nickname because she fueled the sexual urges of local men in her younger days.

One morning, I decided to go canoeing on the long, narrow body of water, known as Grand Lake, adjacent to my cabin. I put my canoe in the lake just north of a cascade called The Rapids, and although I paddled it in a more or less easterly direction, it moved in a northerly direction. Since I knew there was a short stretch of fast water at the lake’s entrance, I wasn’t too concerned, but once I’d gone beyond that stretch, a strong tail wind began pushing the canoe yet more swiftly north.

After an hour or so of having crests of froth splatter my face, I figured it was time for me to paddle ashore. The wind seemed irked by this decision, for now it began blowing from what seemed like all points of the compass with renewed energy, as if it was saying, “I’m the boss around here.”

The canoe responded to the wind’s arrogance by zigzagging maniacally in one direction, then another, while completely ignoring my paddle strokes. This is getting serious, I thought, and my paddle strokes felt like they were being made by person stronger than I am. When I was 10 or 15 feet from the shore, I grabbed the canoe’s rope and hopped into the water.

All at once I saw a mink skittering along the shore. Contemplating this sleek critter, I forgot to contemplate the rope in my hand, and a gust of wind easily jerked it loose. I watched the canoe move toward the middle of the lake…without me in it. I had no choice but to splash my way out of the water…without the canoe.

I felt like I was marooned in the middle of nowhere. There were no roads or even trails in the vicinity, and the nearest dwelling was on the other side of the lake. On the lake itself, there was no boat other than the dwindling speck of my canoe.

What to do now? I thought about hiking back to my cabin, but this would have been impossible because the cliffs along the shore would bar my way, so then I considered taking an inland route. Easier said than done, for shortly after I walked away from the shore, I encountered a dense jungle of alders. I engaged in hand-to-hand combat with these apostates of the birch family, and the apostates won.

All of a sudden I heard my stomach growling. No, it was a bear growling. No, it was actually my stomach growling. As I seemed unable to distinguish between these two different types of growls, I wondered if I might be losing my mind, but concluded that, no, I was just feeling very hungry. After all, the caribou jerky, the tins of sardines, the apple, and the peanut butter sandwiches I’d brought along for the trip currently resided in the canoe.

I tried to look on the positive side — at least the wind was keeping Labrador’s voracious hordes of black flies and mosquitoes from sucking my blood. Tried and failed. Better to be sucked dry by these damned insects than to meet my so-called Maker here, I thought.

I’d been stuck on the shore for five or six hours when I saw a motorboat skimming across the lake. Or rather the wake of a motorboat. I hollered and waved my hands frantically. Did the boatman see me? He seemed to be heading away from me…

…but he was actually tacking and swerving to avoid the lake’s waves. At last he opened the boat’s throttle so that he was roaring toward me. Soon the fellow in the boat — a local man perhaps in his mid-fifties — came close enough for us to shout at each other.

“Hey, aren’t you the guy who’s stayin’ in Miss Gasoline’s cabin?” he

said, raising his voice above the wind. “Grand Lake’s been kickin’ up a fuss with you, eh?”

“I was canoeing and got whacked by the wind,” I shouted back. “My canoe is probably on the other side of the lake now.”

He shook his head in amazement. “You didn’t hear the forecast of 30 knot winds?” he said. “That’s not a problem for me ‘cause I have a motorboat, but a canoe…”

I decided not to tell him that I regard weather forecasts as fictional and seldom listen to them.

The fellow gestured for me to climb into his shallow draft aluminum boat, and once I did, we motored three miles across the lake to where my canoe was bouncing in the water along the shore. My benefactor tied the canoe’s rope to his boat, and we soon made it to my cabin because we were now going with the wind rather than against it.

“Nice to have the right sort of boat, eh?” the man grinned.

I thanked him profusely for his help, then I pulled the canoe ashore, this time grasping the rope firmly, indeed emphatically.

In the cabin, I made myself some coffee, and in my haste to drink it, I raised the cup too quickly to my mouth and spilled most of the coffee on the floor. Another blunder, but one that was somewhat less serious than the one I’d recently made when I gazed at a mink.

Once upon an earlier time, I wanted to meet real-life headhunters (where I live, there’s only the corporate variety), so, finding myself in Borneo, I boarded a motorized dugout canoe and traveled down a series of rivers until I reached an Iban longhouse.

The rivers had provided me with relief from the heat and humidity, the former of which was in the high 90s and the latter of which seemed to be in the high 100s. I felt like my bones were melting and becoming butter.

“You seem to be hot,” an Iban man said to me through Bakhri, my guide and translator, shortly after I arrived at the longhouse.

“Yes, very hot,” I replied, mopping my brow.

“We’re having a cold spell,” the man told me. Whether or not this was meant as a joke, I never found out.

Soon I was seated on a mat next to the chief, a bronze-skinned, middle-aged man whose arms were embellished with a circuitry of blue-black tattoos.

I asked him whether there were any Japanese heads in the longhouse. For Japan had invaded Borneo during World War II, and the government initiated a “10 Bob a Knob” program, whereby the Iban received 10 shillings for every Japanese head they brought in.

The chief shook his own head in response to my question. Then I asked him if the Iban still took heads, and he shook his head again. The Iban didn’t take heads anymore, he said.

“Not even to stay in practice?” I asked.

He shook his head yet again, then added that, in his father’s time, the most popular guy with the girls was the one who took the most heads. If a man didn’t participate in headhunting raids, he probably would end up a bachelor. But nowadays there were fewer bloodthirsty ways to get ahead (so to speak). A young man could go to work in the oilfields of Brunei and bring back a sewing machine for the girl who interested him.

I asked an attractive teenage girl seated near me which she would prefer, a sewing machine or a freshly plucked human head. “No want head!” she shouted in broken English as if she thought I was coming on to her.

The chief realized my dilemma. He brought out a cell phone, probably the first device of this sort I’d ever seen (in certain respects, I’m more backward than ex-headhunters), called up another longhouse, and asked if they had any old World War II heads. As it happened, the other longhouse had quite a few of them.

So it was that I climbed into the canoe with Bakhri, and we traveled to that

other longhouse. There the chief happily showed me a rattan bag of “knobs” that belonged to former members of the Japanese Imperial Army. One of these skulls had a pair of spectacles affixed to its hollow sockets.

After wandering around a bit in the local rainforest, but only a bit because

the humidity was melting me, I returned to the longhouse and looked at the bag of skulls again. This time, I noticed an interesting fungus growing on one of them and — being a mycologist — I began scraping it off so I could study it and perhaps identify it.

“Don’t do that!” shouted Bakhri.

“Because the skull is a ritual object?” I asked him. For I’d read somewhere that skulls taken in battle could ward off evil spirits and likewise improve the yield of rice fields.

“Tourists take pictures of these heads,” Bakhri said. “They won’t want to take a picture of one that’s got a big scrape mark on it. If they see it, maybe they’ll complain to the chief…”

Not long after he said this, a boatload of tourists did in fact arrive at the longhouse, and I soon began hearing the whizz-clicks of cameras. All at once, an unpleasant thought occurred to me — namely, that I was a tourist myself.

Once upon an earlier time, I joined a group of Russian scientists on an expedition to Siberia’s Wrangel Island. The purpose of our trip was to document the flora, fauna, and fungi on this remote island in the Chukchi Sea.

Since Wrangel has the largest density of denning polar bears of anywhere in the world, we were obliged to carry a firearm or a can of Mace with us at all times. Being a lousy shot, I chose the latter.

“You need vodka, too,” a Russian botanist informed me, energetically puffing on a Troika cigarette. “Otherwise, you won’t be able to identify unusual species.” He handed me a 1.75-litre bottle of Hammer & Sickle Vodka.

Here I should mention that Wrangel’s landscape remained unscathed by Ice Age glaciers, with the result that it’s more or less been unchanged in the last million years. Endemic species abound. The island boasts 23 plant species found nowhere else in the world, and perhaps half as many endemic butterfly species. Small wonder that it’s become a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

So there I was, wandering the sedge tundra on the eastern side of the island. In a rocky outcrop, I saw a Muir’s fleabane (Erigone muirii), a flowering plant in the aster family first documented by the American naturalist John Muir on an 1881 visit to the island. A short while later, I saw a small, brownish mushroom that turned out to be a previously undescribed Inocybe species.

Then I saw a heap of polar bear shit (poop is an inappropriate word) festooned with seal whiskers, berry pits, a delicate maze of birds bones, and what looked like some kelp. What a splendid work of art! I said to myself.

In a short while, a powerful wind called a yuzhak began blowing, snarling, and whistling across the tundra. Plants such as cotton grass, bladder campion, and alpine arnica as well as Muir’s fleabane sashayed back and forth, repeatedly back and forth, as if they were performing some sort of exotic dance. None of them seemed in danger of being blown down, while I felt like I was constantly at risk of being swept into the Chukchi Sea.

Suddenly I saw an ATV coming in my direction. An ATV seemingly running on its own, without any driver. Would Wrangel Island’s wonders never cease? Then I saw the botanist who’d given me the vodka hunched low against the vehicle’s wheel to escape the blasts of the wind. He saw me and immediately stopped.

“Want to see the northernmost outhouse in the world yet?” he shouted, then gestured for me to hop into his ATV.

Fifteen minutes later, we reached what turned out to be a lavatorial relic from Soviet times. Its wooden walls had mostly collapsed, its floor was a mass of moss, and its lichen-covered seat was not even a semi-circle. What remained was tilted precariously to the starboard. Northernmost outhouse or not, it didn’t seem to care about being listed in the Guinness Book of Records. To hell with celebrity! its ruins seemed to proclaim. All I want is to become part of the remote bounteous earth.

In the remote village of Uelen in Siberia’s Chukotka, there aren’t any restaurants. No takeouts or curbside deliveries, either. So I went foraging for mushrooms on the local tundra, and I soon collected enough Scaber Stalks (Leccinum scabrum) to feed me for several days, assuming I accompany them with something like walrus blubber. For mushrooms require more calories to digest than they contain, so it’s a good idea to eat a fatty food along with them.

On another day I went foraging with a local schoolteacher named Umqy (Polar Bear). We happened on a fruiting of Amanita muscaria, which the Chukchi call wapak. This red-capped, psychoactive mushroom with rings of white warts on its cap is an iconic species, appearing in Alice in Wonderland as well as on postcards and stoner websites.

Traditionally, the Chukchi ate A. muscaria in order to get in touch with their ancestors, and upon doing so, they’d ask those ancestors about (for example) how to get rid of the viral infection afflicting their reindeer or whether a potential wife would be a decent mate.

“With a wapak, you don’t need a ticket or a boarding pass,” Umqy said, a grin on his face. For the mushroom typically makes you feel like you’re flying.

Here I should mention that Chukchi who ate wapaks in Stalinist times were regarded as enemies of the state because they were engaged in a highly individual rather than a communal act. Reputedly, those who ate wapaks were forced onto a plane, and once the plane was in the air, the cargo door would be flung open.

“You say you can fly,” a Stalinist henchman would announce. “Okay — then fly…” Whereupon he would push his victim out of the plane.

Even today, most Chukchi are reluctant to talk about cultural matters with Russians, so planted in their genes are incidents from the Soviet era. We have no wapaks in our area, a Chukchi elder told a Russian ethnographer of my acquaintance. But since I wasn’t Russian, Umqy happily shared his lore with me. For example, he gave me the following instructions on how to pick wapaks:

You should be extremely careful with the cap. If you damage it, you might end up with some sort of head injury. If you remove the warts from the cap, you might end up losing all your hair. And if you injure the stem, something unpleasant will happen to one of your legs.

“How unpleasant?” I asked.

“The leg might need to be amputated,” he replied.

I’d heard that only a shaman was allowed to eat the mushroom in earlier times, and then his followers would drink his urine. For muscimol — the primary trip-taking alkaloid in A. muscaria — passes through a person’s system more or less unaltered.

I asked Umqy if he had ever drunk the urine of a shaman.

“We hardly have any shamans anymore,” he said. “But I once drank some of my own mocha (piss) after I ate a few wapaks. I didn’t fly very far, though…”

I decided to eat some wapaks myself. So I gathered a few, being very careful not to damage any part of them. Umqy then told me that I had to bare my naked buttocks to the moon just before I ate them, or I would suffer from a prolonged bout of bad luck. When I lowered my trousers and raised my buttocks, Umqy and a few of his friends burst into riotous laughter.

“We’ve made a joke on you,” Umqy said.

“Luna ne naplevat' na tvoyu zadnitsu!” one of his friends remarked. Which means, “The moon doesn’t give a damn about your ass” in Russian.

But how did I feel after eating the mushroom? As it happened, I didn’t fly off to visit my ancestors, wherever they happened to be, but I did feel euphoric, an emotion somewhat unusual for me. In fact, I felt so upbeat that I joined the other individuals in laughing at the sight of my naked buttocks.

Let me conclude by saying that most Chukchi don’t eat wapaks nowadays. Instead, they drink vodka, lots of it. I can imagine their ancestors feeling very lonely, with almost no one visiting them anymore.

On one of my visits to Greenland’s capital Nuuk, I went to an open-air market called Braedtet (The Plank) in search of my supper. Displayed on tables as well as piled on the ground, I saw dead kittiwakes, briskets of reindeer, walrus aortas, dried whale meat, mikiaq (decomposing seal heads), and various types of fish, along with head-shot seals skinned to the nose and hung vertically on ropes.

Needless to say, there were no carrots, cauliflower, asparagus, or brussels sprouts. Soon, a short woman with a soft round face and shoulders like a fullback’s tried to interest me in buying some qimmeq (dog). She pointed to some light brown meat lying in a heap on a table.

“Qimmiaraq [puppy]?” I asked. For I knew that the puppies of sled dogs were occasionally strangled and their fur used to provide trim for a child’s parka. Might a dead puppy sans fur be sold as cuisine?

The woman shook her head, uttering a word I didn’t catch — maybe the local word for an adult dog that had become unmanageable or one that had outlived its usefulness as a sled animal, and whose sole purpose now was to be eaten. (Note: As the custom of using sled dogs has declined in Greenland, so has the custom of eating them.)

Unlike explorer Vilhjalmur Stefansson, who balked at the idea of eating man’s best friend (woman’s best friend, too), I had no qualms about doing so myself. Indeed, I was curious about the taste of a former sled dog. So I asked for a pound or so of the meat. After the woman took my kroner, she handed the meat to me, saying, “Nerilluarisi! [Bon appetit!]”

Back at my tent I cut the meat into chunks and cooked those chunks for a relatively long time over my Primus stove. Since I didn’t have any basil, dill, oregano, garlic, or thyme with my gear, I was obliged to eat the meat without a seasoning. But this at least gave me a good idea of how Greenlandic sled dog actually tastes.

How, in fact, did the meat taste? For starters, it was so chewy that I felt like I was eating mostly muscle and sinew, as might be expected from an animal that had devoted its entire life to pulling sleds. It also had a strong but rather generic animal flavor. Even though its primary food had been fish, the meat did not have a fishy flavor. If I wanted to be off-putting, I’d say that the taste reminded of the smell of a wet dog. A kinder way to describe it would be to say that it would have benefited from some hot sauce.

Here’s perhaps a still kinder way to describe it: By dining on a Greenlandic sled dog, I was again putting to work an animal that had dedicated its life to working for my species.

The Norwegian Paul Bjorvig (1857-1935) usually isn’t considered a explorer, yet compared with some of the pre-Monty Pythonesque individuals on whose expeditions he took part, he was indeed an explorer. An explorer whose travails north of latitude 66˚ he accepted quite naturally, as if they were intrinsic part of the terrain. What follows is the best-known of those travails…

In 1898, Bjorvig signed on as an ice pilot in a North Pole expedition led by two unlikely Americans, a Chicago journalist named William Wellman and a Missouri alcoholic named Evelyn Baldwin. The expedition used Russia’s remote Franz Josef Land as a base camp to reach the Pole, but the leaders spent most of their time roaming the archipelago and giving (in the words of Wellman) “islands, straights, and points good American names.” For some reason, they thought Russian names were inappropriate for a Russian place.

While the two leaders were engaged in their roaming, Bjorvig and another Norwegian, Bernt Bentsen, remained in an ice cave named Fort McKlinley after the then-U.S. president William McKinley, and looked after the expedition’s supplies. A team of sled dogs shared the cave and sometimes used that cave, not to mention the two mens’ sleeping bags, for their lavatorial needs.

This habitation was only forty miles southeast from one of the ice caves that explorer Fridtjof Nansen shared with his expedition mate Hjalmar Johansen a few years earlier. In fact, Bentsen had spent three previous years in the Siberian Arctic on Nansen’s ship the Fram, but his quarters on that celebrated polar vessel were luxurious compared to the ice cave he shared with Bjorvig.

Having become increasingly ill, probably from scurvy, Bentsen died in January of 1899. His last request to Bjorvig was: “Please don’t let a polar bear eat my remains.” Bjorvig promised to honor this request.

As it happened, the only way to keep a polar bear from eating Bentsen

was to keep his body in the ice cave. So Bjorvig wrapped Bentsen’s body in