Austrian extreme skydiver Felix Baumgartner, the first person to break the sound barrier during a freefall jump, has died in a paragliding accident.

Baumgartner, 56, was paragliding in Italy’s central Marche region yesterday when he lost control and crashed. He fell to the ground near a hotel in the town of Porto Sant’Elpidio. The town's mayor, Massimiliano Ciarpella, said that reports suggest Baumgartner may have suffered a cardiac arrest while flying.

The man who jumped from the edge of space

Baumgartner is best known for a 2012 jump in which he skydived from a balloon on the edge of space. The project, called Red Bull Stratos, resulted in several firsts. Leaping almost beyond gravity in a custom suit, Baumgartner plunged toward Roswell, New Mexico, faster than the speed of sound.

During a nine-minute descent, he set three world records, including Maximum Vertical Speed (1,357.6kmph, 843.6mph/Mach 1.25), Highest Exit Jump Altitude (38,969.4m, 127.852.4ft), and Vertical Distance of Freefall (36,402.6m, 119,431.1ft).

A former Austrian military parachutist, Baumgartner had a long career spanning thousands of jumps. In 1999, he parachuted from the Petronas Towers in Malaysia, and in 2003, he flew across the English Channel using a carbon fibre wing.

On July 3, in a remarkable bit of quick thinking, a Vietnamese farmer used his drone -- usually used to spread fertilizer -- to save two children from a flooded river.

Tran Van Nghia was working his land in Gia Lai, in Vietnam's central highlands, when he heard a cry for help from the nearby Ba River. Speaking to local news organization Tuoi Tre Online, Tran explained that some children had been herding cows across the river when a sudden surge of water -- likely from monsoon rains upstream -- trapped them off on a fast-submerging island in the middle of the river.

Locals tried to swim to the children, but the current was too strong, and instead, people rushed off to find a canoe. But with the water rising quickly, Tran felt forced to act. He attached a rope to his drone and proceeded to airlift two of the three children from the fast-disappearing island. The third child was then rescued by canoe soon after.

You can see two videos of the rescue below:

It's the height of the climbing season on Alaska's Mt. McKinley, with 433 climbers on the mountain and 395 climbers already finished. The National Park Service has its hands full with avalanche rescues and frostbite patients, while an American climber announces the first ever solo of the legendary Slovak Direct route.

Another death on the West Buttress route

Just a few days after ski mountaineer Alex Chiu fell to his death on the West Buttress route, there has been another death. On June 10, a soft slab avalanche caught American Nicholas Vizzini, 29, and his partner below the Rescue Gully above Camp 14 on the same route.

"Two mountaineering rangers on an acclimatization climb spotted the partner on the surface of the avalanche debris and were able to respond within minutes," the National Park Service (NPS) said in a statement the next day. "During the search, Vizzini was visually located and found mostly buried in the debris. The rangers immediately began digging to establish an airway. CPR was initiated but discontinued after forty minutes due to traumatic injuries and no pulse."

Four days later, another avalanche swept through Rescue Gully, catching a skier who was lucky to escape without injury.

First solo of the Slovak Direct

Established by Slovak climbers Blazej Adam, Tono Krizo, and Frantisek Korl in 1984, the Slovak Direct is a difficult, technical route that rises over 2,700m up McKinley's towering South Face. Graded VI, 5.9X, M6+, WI6, A2, it has had fewer than 20 total ascents.

American Balin Miller claims to have just notched the first recorded solo on the route.

"Fun times with high pressure on the South Face. A more casual ascent at about 56 hours, with 70% of that time spent sleeping," Miller wrote of his climb on Instagram.

Miller is just 23, and his 56-hour solo push is remarkable, clocking in four hours faster than Mark Twight, Steve House, and Scott Backes' groundbreaking 60-hour push in 2000.

According to Climbing Magazine, Miller left Base Camp on June 10 and climbed the route over three days, with a lengthy 19-hour first bivy.

On June 2, ski mountaineer Alex Chiu, 41, of Seattle, Washington, fell to his death on Mt. McKinley.

Chiu was climbing the West Buttress route with two partners when he fell on an exposed 900m face near Squirrel Point. He was unroped at the time. His partners lowered themselves over the edge to look for him, but could not see or hear Chiu. They then descended to the lower camps to seek help.

High winds and snow slowed rescue operations, with helicopters grounded on June 3. On the morning of June 4, the weather cleared, and National Park rangers recovered Chiu's body after an aerial search.

The NPS reports that 500 people are on the mountain, a significant uptick from the end of May, when 230 climbers were active.

The climbing season has begun on Mt. McKinley, though unsettled weather meant a slow start. In the most recent update from the National Park Service (NPS), 936 climbers have registered to climb the peak, with 230 currently on the mountain and 17 climbers already back home after early expeditions.

Expeditions started to fly in during the first week of May, but there's limited information available on teams and goals so far.

Accidents

On May 19, a climber fell 15m and broke his ankle while leading a pitch near Mount Hunter's North Buttress. With the help of a nearby climbing pair, the injured man's team managed to lower him eight pitches down to the base of the route. There, they met up with NPS rangers and moved him to a safe location for helicopter evacuation.

Elsewhere, skier and climber Anna Demonte had been acclimatizing in preparation for a Fastest Known Time (FKT) ski attempt on McKinley. Demonte set the women’s ski FKT on Mont Blanc last year with a time of 7 hours and 29 minutes.

Unfortunately, while skiing with partner Jack Kuenzle at around 5,000m, Demonte fell in sloughing snow and tore her MCL. She managed to ski down to Base Camp, but her season and the FKT attempt are over.

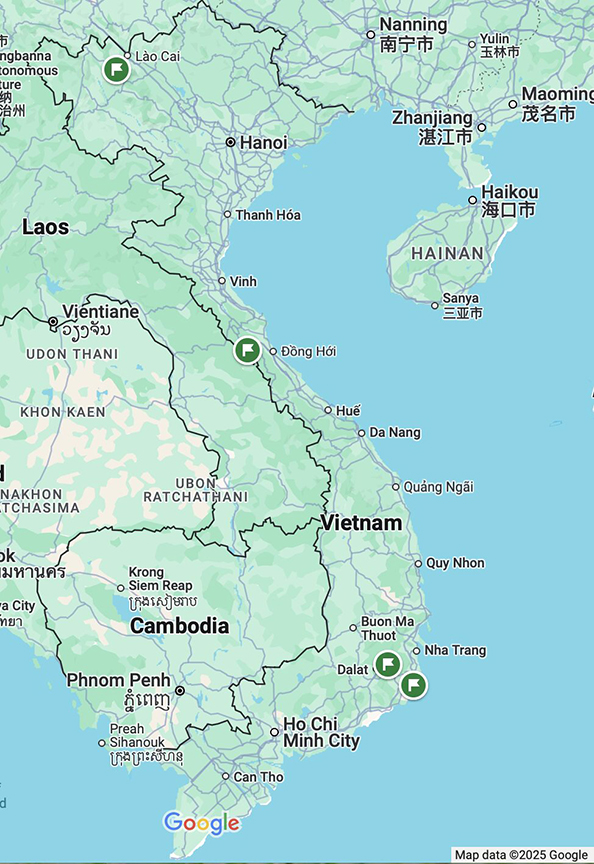

Most travelers don't consider Vietnam a hiking destination, but take it from someone who lives there: The country has plenty of great treks if you know where to look. In the north, the Hoang Lien Mountains are the tapering, tail-end of the Himalaya; in the south, the Da Lat Plateau rises sharply from sea level to over 2,000m, and the underexplored Annamites line Vietnam's spine.

We look at four accessible hikes for those looking to escape Saigon's eight million scooters.

Fansipan Mountain

Let's start with the roof of Vietnam, 3,147m Mount Fansipan, the highest peak in the Hoang Lien Mountains. These run along Vietnam's rugged northern border with China. The summit has been extensively developed, with walkways and two pagodas at the top of an (admittedly beautiful) cable car ride that leaves from near the local town of Sapa. However, for those who'd like to summit on foot, this is a hard, no-frills two or three-day hike through dense jungle.

Different routes

The most direct route begins in the stepped rice paddies just outside Sapa. From the ethnic H'Mong village of Sin Chai at approximately 1,260m, the trail quickly disappears into the forest in Hoang Lien National Park. Though this is the shortest way to the summit (the ascent can be completed in a day), the trail is unclear, and it is easy to get lost. Instead, most independent hikers and guided groups do the Tram Tom Pass Trail.

The summit can be reached in a day on the Tram Ton Pass route too, depending on the weather and your fitness. However, there are two camping areas en route for those who would prefer to take their time. The first is at roughly 2,200m, and the other is fairly near the summit, at 2,800m. The trail starts in dense forest before climbing to exposed, undulating ridgelines. The final section to the summit is very steep.

The longest route starts at Cat Cat Village and runs approximately 20km. This trail has the most altitude gain at around 1,900m, and it takes three or four days if you also descend on foot.

Nui Chua (God Mountain)

Perhaps the least-known hike on this list, Nui Chua Mountain is not very high, only 1,039m. Situated on Vietnam's south-central coast in Ninh Thuan, the hike still requires almost 1,000m of elevation gain. This region is extremely dry, and the heat makes what should be an easy two-day hike more challenging.

Inside a national park, a guide is required for the hike to Nui Chua's summit. Most of the guides are Raglai -- one of 54 ethnic groups in Vietnam -- and speak a different language from the majority Kinh. Part of this hike's appeal is the guides' knowledge of the forest here. They will stop to pick fruits you've never heard of and collect herbs that grow only at specific elevations to cook with dinner. Both times I've done this hike, the evening meal has been incredible, with chickens roasted over an open fire and the guides producing homemade rice wine. The campsite sits in a grassy clearing created by bombing during the American War. (The Western world tends to call it the Vietnam War, but the Vietnamese, understandably, do not.)

The next morning, you climb to the summit, passing through chunks of primary mixed forest interspersed with swaying grasslands. Then it's a unrelenting descent back down to a Rag Lai village on the edge of the park.

This national park is rarely visited by tourists, so knowing some Vietnamese or traveling with a Viet would make organizing this hike much, much easier.

Bi Doup Mountain

At the southern end of Vietnam's Central Highlands, Bi Doup Nui Ba National Park is an enormous sweep of forest and mountains just north of the city of Da Lat. There are plenty of good hikes possible in Bi Doup Nui Ba, including to 2,287m Bi Doup Mountain, the highest point in southern Vietnam.

The trail starts from a forest ranger station near Da Chais, about 40km from Da Lat. It's a relatively easy two-day hike covering around 26km, first through pine forest and then through mixed broadleaf forest as you get deeper into the park. Getting to Bi Doup's summit requires some scrambling for the steep final ascent. The overnight campsite is at 2,000m.

The area around the mountain is particularly good for several rare bird species endemic to the Da Lat Plateau, such as collared laughingthrushes, white-cheeked laughingthrushes, and Vietnamese cutia.

After the peak, most hikers head out through coffee plantations to emerge back in Da Chais near the village of K'long K'lanh.

Son Doong and Phong Nha-Ke Bang

Discovered in 1990 and first surveyed in 2009, Son Doong is the largest cave in the world by volume (38.5 million cubic meters). It's an expedition to get there, requiring a huge team of porters and guides, and only one company is currently allowed to take tourists: Oxalis Adventure. As a result, it's extremely hard to get a place on an expedition (only 1,000 places are available per year, and they book up far in advance) and expensive for Vietnam ($3,000). But for those with the money -- and who are prepared to wait -- it's one of the world's best adventure treks.

The expedition begins from Phong Nha in central Vietnam and takes four days through the jungle of Phong Nha-Ke Bang National Park. Hikers cover 25km (with 8km inside caves), and the trip requires some basic climbing and rappelling with safety equipment, including climbing a massive rock wall inside Son Doong, nicknamed The Great Wall of Vietnam.

Along with the great wall and an underground river, collapsed ceilings have created unique jungle ecosystems inside the cave, inspiring the first cavers to name the area "Watch out for Dinosaurs."

If your budget doesn't stretch to Son Doong, there are over 400 more caves to explore in Phong Nha-Ke Bang.

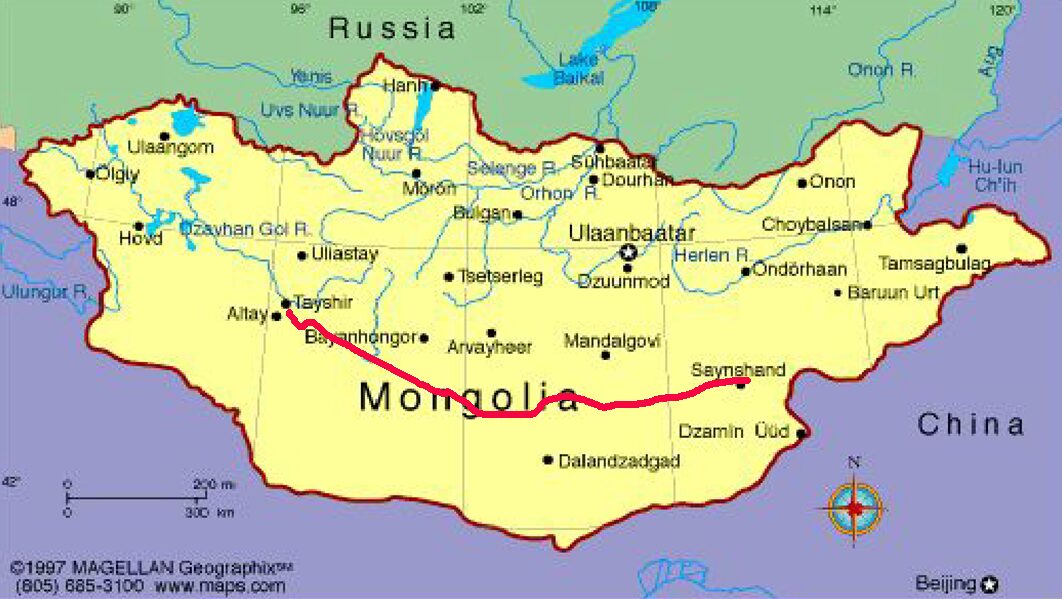

Polish adventurer Mateusz Waligora just can't get enough of the Gobi Desert. Having slogged 1,785km across the Mongolian Gobi pulling a cart in 2018, he returned in February to cycle 1,400km by fat bike.

Waligora started in the western Altai region on February 19. At the outset, his rig was heavily laden. He dragged a trailer loaded with 21 liters of water packed in thermoses, carried 35kg of food, and had two fuel systems because he believed it would be hard to find clean white gas.

A mild winter

Last winter had been very cold in the Gobi, with lots of snow and temperatures as low as -30°C, and Waligora was banking on a milder year. The first stage in the Altai was very cold, but as he moved east, his prediction looked prescient. Temperatures "soared," peaking at 4°C. However, the mild conditions worked against him. With the snow and ice thawing, the ground softened, and he found himself cycling through treacle. Worse, claggy mud collected on his tires. The mud built up until there was no space between the wheels and the frame of his bike, necessitating stops to clean it off by hand.

With the heavy bike, progress was slow, and Waligora had to change his tactics. He found that some of the local gas worked well enough that he'd be able to melt ice and snow for some drinking water, so he ditched some of the thermoses, replacing them with lighter plastic bottles.

"However, I did manage to melt a hole in my tent while melting drinking water," Waligora told ExplorersWeb.

More paved roads

The Gobi had changed a lot in the seven years since his last trip, and Waligora was surprised to find paved roads and 5G in some of the villages he cycled through. It was also Lunar New Year during his journey, and the Gobi was unusually busy with people returning to their home villages to celebrate with family. This would prove fortunate.

On his way to the village of Boulgan -- a tough stretch with no villages during which he had to rely on wells for water, unsure if they'd be frozen -- his crank bearings broke (in the arm that connects the pedals to the bottom bracket of a bicycle). Unable to cycle and still 125km from the village, he considered pressing the SOS button on his Garmin InReach.

"I knew it was over, I couldn't do anything [to fix it]. I considered the SOS button, but I have never used it before, and I believe that if you get into trouble, you still have to be self-sufficient. You need to do your best to get yourself out of the situation. So I calculated my water and worked out that I could walk, pushing my bike, to Boulgan," Waligora explained.

After 5km of pushing, he saw a car. But his hope of rescue evaporated when he saw it was stuffed with 14 people, doubtless returning home for the Lunar New Year. Fortunately, they were more than hospitable, strapping his bike to the roof and cramming him in as far as the village. From there, he traveled to a regional hub and arranged for new bearings to be sent from Ulaanbaatar.

Camel cheese

Getting back to the point he'd left his route proved hard. Nobody wanted to drop him by car back in the middle of nowhere. Instead, he elected to restart his cycle from Boulgan, leaving a gap of 125km in his route.

"On my previous expeditions, it was a point of honor to remain unsupported. In 2018, I tried to refuse gifts of camel cheese. But I don't speak Mongolian and had to take them and then pass them on to other people as gifts. In Antarctica [Waligora skied to the South Pole in 2022], the rubber absorber that protected my back while pulling the sled broke, and I refused a new one [to remain unsupported] and screwed up my back. It was such a stupid decision. This time I didn't give a shit...it's my adventure, and I'm not competing with anyone," Waligora said.

From Boulgan, he made good progress, despite plenty of broken spokes, until very close to the end. Then, 25km from his finish line, the bike's frame finally broke from the weight. Again, it was not possible to repair. He'd have to finish on foot.

Waligora still had the GPS coordinates from his 2018 expedition and chose to retrace his footsteps, camping in the same spot before he finished in the small town of Sainshand.

Waligora had covered 1,285km in 26 days. "I was aiming for 50km each day to ensure I had enough food to finish. I would cycle further if I had enough light, but I didn't cycle after dark because it was very cold for changing punctures, which I'd suffered plenty of in 2018 [on his cart]. At night in winter, it might be -20°C, so sorting an inner tube puncture would be very difficult."

Not as scary

It was a tough trip, with brutal winds and big temperature fluctuations, but he thought it was easier than his foot crossing.

"I maybe had a 10-15% chance to finish the foot crossing. There was no one with the knowledge to help me. It took three years of preparation. I knew that this bicycle expedition would be a little bit harder because of the climate; it would be colder, with winds from the west and north because of Siberia. But I had more experience with the Gobi this time, so it wasn't as scary."

But that doesn't mean he wasn't relieved to finish. "It was a lot of fun, but I can't recommend cycling the Gobi in winter," Waligora said. "I lost a tooth on frozen chocolate in my second week...I had to file it down with my multi-tool to take the sharp surface off. There were hard moments."

And yet, despite the hardships, Waligora doesn't think he is done with the Gobi. It's under his skin now.

"I love this place. I'd love to return, perhaps with my son. Maybe we could walk the central sands with camels."

Will the Barneo Ice Camp finally open this year? It looks like it will, though the website is in Chinese, and getting there will require traveling through Russia. Whether or not we get a proper North Pole season for the first time since 2018, there will be a handful of interesting Arctic expeditions this year in Canada and Greenland.

Ellesmere Island

Polar veterans Borge Ousland and Vincent Colliard will head to Ellesmere Island for the next stage of their Ice Legacy project. They are aiming to ski across the 20 largest icefields on Earth. Last October, they crossed the Juneau Icefield in Alaska, their ninth of the 20.

On Ellesmere, they'll leave from Ward Hunt on the northern tip and ski south, almost the entire length of the island, to the small community of Grise Fiord. They plan to cover 1,000km over six weeks and use "ski sails," which presumably means kites, for sections of the route.

They are due to begin in April.

Baffin Island

A British team consisting of Tom Harding, Ben James, Leanne Dyke, and James Hoyes is planning a mixed-discipline trip on Baffin Island. In early April, the team will fly to Pangnirtung before a 60km snowmobile journey to their start point.

"From the Kingnait Fiord, the team will first ski towards the Rundle Glacier before traversing south to the Gateways Glaciers. The distance from our drop-off point back to Pangnirtung is approximately 110km, but we expect to cover more than this exploring the area," they explain on their website.

The team will drag pulks on their ski traverse while also attempting to climb some of the region's peaks.

Northwest Passage

Jose Trejo, Sechu Lopez, and Francisco Mira are planning a 760km ski and pulk expedition from Resolute to Gjoa Haven in the Canadian Arctic. They plan to pull 120kg sleds and are budgeting around 40 days for the journey.

"The three of us are normal people who simply do unusual things. We are not young...but we belong to the select group of old people who are well," Lopez wrote of their team.

The Spanish trio will leave Madrid for Canada on March 22.

Meanwhile, as previously covered, Anders Brenna of Oslo will set out in mid-March to manhaul 1,100km solo, from Gjoa Haven to Glenelg Bay on northern Victoria Island.

Ungava

In the Nunavik region of northern Quebec, Dave Greene and his partner are planning a 25-day, 543km ski expedition across the Ungava Peninsula from west to east. Starting in Hudson Bay, they will end in Ungava Bay, Nunavik.

The expedition is scheduled for March.

Also in Ungava, four women are already underway skiing 650km from Schefferville to Kangiqsualujjuaq. Kathleen Goulet, Chantal Secours, Julie Gauthier, and Roxanne Chenel are following a well-known wilderness canoe route down the Rivière de Pas and the George River to an Inuit town on Ungava Bay. They set out at the end of January when the rivers are solidly frozen.

Greenland

A team of five, including Finn Jussi Uusitalo, plans to kite-ski from Kangerlussuaq to Qaanaaq, the last sizeable town in North West Greenland. Their trip should take about a month and cover between 1,600 and 2,000km.

Another team plans to go south to northwest. Adeline Gervais and an unnamed expedition partner plan to leave the southern coast with 50 days of food (though they hope the expedition will take around 40 days) and travel over 2,200km. They will snowkite, with Gervais using a snowboard-splitboard and her partner using a more traditional kite-ski setup.

The pair plans to set off in mid-April.

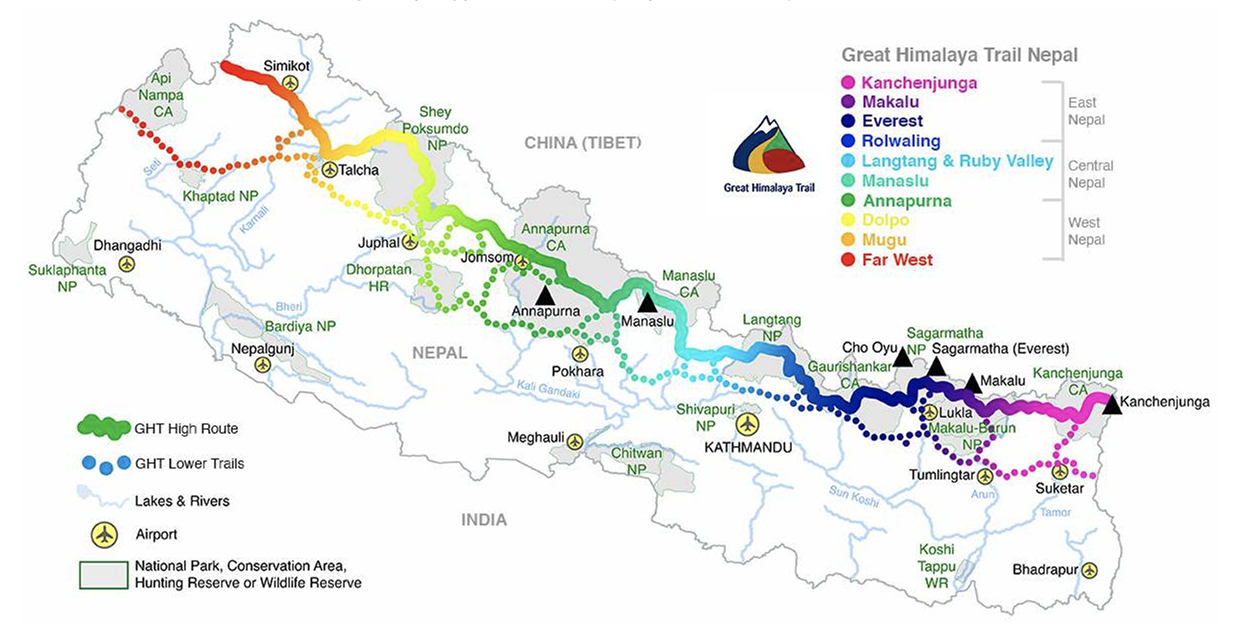

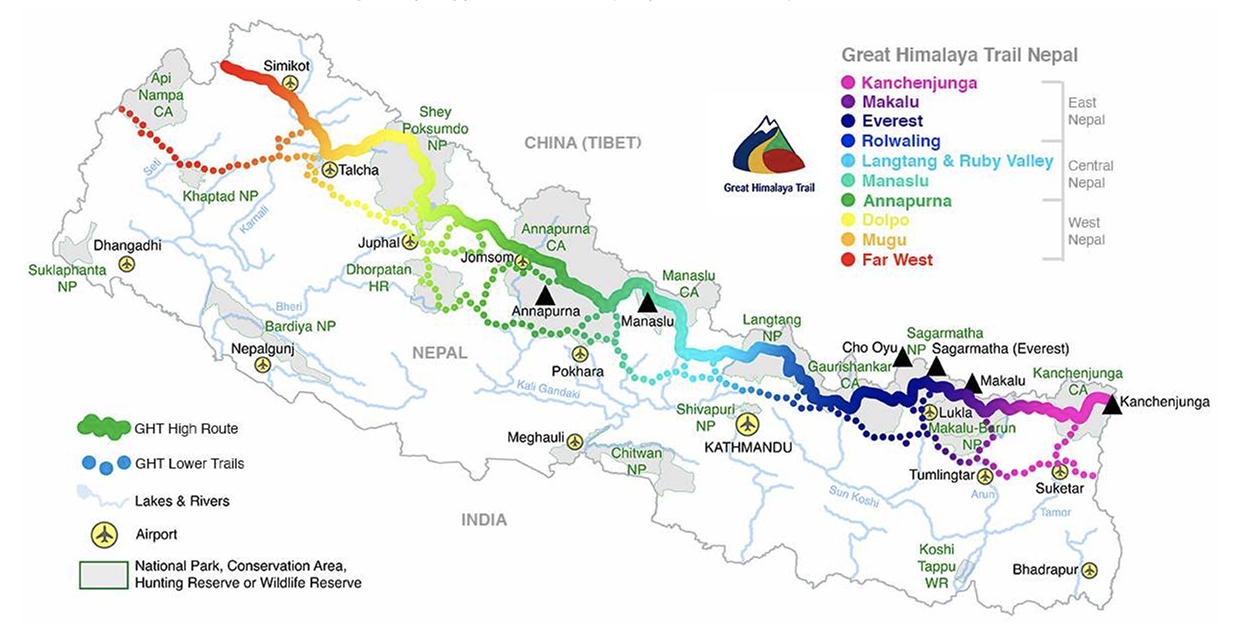

Nepal's Great Himalaya Trail runs 1,750km across the entire country and passes over some of the highest trekking passes in the world. Here in Part II, we examine the route and hear from those who have completed the GHT. You can check out Part I here.

Rolwaling

Tashi Labsta (5,760m) is quite technical and can require fixing ropes. Rockfall can be a problem here. Like Sherpani Col, weather and snow/ice conditions might require a flexible schedule. World Expeditions takes two days on the approach to assess the weather and camp high (5,665m) before the crossing. The pass is close to Thame, roughly 10km away, but 2,500m above the village!

Route finding on both the approach and the pass can be tricky if there’s snow. The “glaciers on the eastern side of the pass are hazardous and crevassed,” Boustead explains on his GHT website. Boustead also notes that food can be hard to come by in Rolwaling, so independent hikers should stock up before the pass.

After the saddle, most trekkers descend to the Trakarding Glacier for a cold night’s camping. Jasmine Star, who hiked half the GHT in 2016 and the other half in 2019, described the descent as the most challenging section.

“It’s hard on the way down," she says. "There are some immense boulder fields after the pass. They go on for like a day, day and a half before you reach a proper trail again.”

The next five to seven days are more relaxed, following rivers and meandering through remote villages in Rolwaling. This section of the GHT finishes at Sano Jynamdan.

Langtang and Ruby Valley

The trail then winds through the villages of Listi, Bagam, Kyangsin, and Dipu. This section is “Nepali flat,” meaning undulating without any big climbs. Then, it’s back to ascending, with a 1,000m+ elevation gain to Kharka and then another 500m to Panch Pokhari at 4,074m.

After a couple more days of gradual ascent, there’s the first high pass in some time. Tilman’s Pass (5,308m) involves some scrambling, and loose rock may cause problems, but it should be doable in a day.

After a night camping just below the pass, the route joins the main Langtang Trail. This means teahouses, relative luxury, and a well-trodden, clearly marked trail. Depending on fitness, speed, and weather conditions so far, hikers can expect to be between 60 and 80 days into the GHT at this point, a little over halfway through.

The next few days are known as the Ganesh link of the GHT, connecting Langtang to the Manaslu and Annapurna regions.

Manaslu and Annapurna

The trail now drops like a stone to 1,503m at the small village of Syabru Besi. The next few days follow a similar pattern. The trail climbs to ridgelines and then descends into valleys and basins (later dipping even lower to 970m), with small villages scattered along the route. This area is the Ruby Valley.

Over several days, you gain altitude again, culminating in a crossing of Larkye La at 5,140m. Along the way, you skirt the edge of the Kutang Himal, a natural barrier that marks the border between Nepal and Tibet. With more elevation, there’s also the return of mountain panoramas, with views of Himalchuli (7,893m), Peak 29 (7,871m), and Manaslu (8,163m). In clear weather, there are good views of Annapurna II (7,937m) from Larkye La.

The trail follows the Marsyangdi River downstream, descending quickly. Leaving Manaslu behind, you enter the Annapurna region. The Annapurna circuit is popular, and the trail is clear, with plenty of places to stay along the route.

You gain altitude again toward Thorong La (5,416m), the highest point in the 300km Annapurna circuit. This pass is a long, arduous day. Tour companies offering Annapurna Circuit treks usually list it as the longest day, with a pre-dawn start to avoid the notorious Thorong winds and 9 to 12 hours of hiking required. It’s not technical, but a long, gradual slog, with several false summits and then a 1,500m descent to Muktinath.

With the Annapurna range now behind you, it’s on to Dolpo.

Dolpo

The Dolpo-pa, a semi-nomadic ethnic group of Tibetan descent, inhabit 24 villages in this region. It’s a remote, rugged bit of the Himalaya with few trees, but the trail is mostly well-marked.

“The GHT provides many variations of ethnicities, religions, and cultures, but the Far West is particularly different,” guide Bir Singh Gurung explained. "Dolpo has its own pre-Buddhist beliefs, such as Animism (Bon) religion and pure Tibetan culture."

Gurung has guided in the Nepalese Himalaya since 1999. He said this was his favorite section of the GHT “because of its remoteness, the wilderness, rich culture, and the landscapes.”

After Muktinath, the trail leads to Kharka, before two sub-5,000m passes bring you to the village of Santa. Another day or two takes you to Lalinawar Khola (river), at the base of 5,550m Jungben La, with great views of Hidden Valley and Dhaulagiri, and 5,120m Niwas La. After quite a few days at lower altitudes, these passes can prove challenging, but both can be completed in around seven hours at a steady pace.

After the passes, the trail descends to another river, Chharka Tulsi Khola. The path flicks between the two sides of the river as you move up the valley. Another high pass rears up ahead, Chan La (5,378m), but it has an easy gradient and is not technical.

Descending to the trading village of Dho Tarap, the trail soon climbs again to Jyanta La (5,100m) en route to Saldang, the administrative center for Upper Dolpo. From there, it’s an easy day to Shey Gompa, an 11th-century Buddhist monastery.

The next two days follow the trail across 5,350m Nagdala Pass to the famously beautiful Phoksundo Lake.

The Far West: Rara Lake & Yari Valley

From Phoksundo Lake, you enter Nepal’s Far West, the least visited region in the country and the final segment of the GHT.

Crossing Kagmara La (5,115m) is a long, two-day effort, but the next five or six days are fairly easy. The trail drops and winds through a few villages on the way to Rara National Park and Rara Lake, the largest lake in Nepal.

Depending on your pace (and your start date), the monsoon rains could begin around this time. If so, expect heavy deluges, muddy boots, and leeches.

From Rara Lake, there are two GHT options: From Gamgadhi to Simikot and the Yari Valley, or cross-country to Kolti and Chainpur and on to the Mahakali Nadi River in India. World Expeditions elects to take clients on the Gamgadhi to Simikot and Yari option because “this route travels closer to the center of the Great Himalaya Range.” But independent trekkers will find either route interesting and little visited.

Assuming you take the “upper” route, you leave Rara Lake for Karnali. Following a familiar pattern for the next week, you climb over ridges and then descend into basins and valleys, never surpassing 4,000m and sometimes dropping below 2,000m. At Shinjungma, the main trail branches away, heading further north toward the border with Tibet. It eventually finishes at the town of Hilsa.

How long does it take?

Finishing times vary considerably. The Great Himalaya Trail website suggests 120-140 days, World Expeditions schedules 150 days (including getting to and from start and end points), and some speedy independent travelers knock it over in around 100 days.

Difficulty, fitness, and training

World Expeditions rates the GHT a 9/10 on their difficulty scale (the highest rating of any of their treks), grading it as an intermediate mountaineering expedition. While they don’t require mountaineering knowledge, they do check fitness levels and previous hiking experience when people wish to sign up.

Heather Hawkins completed the GHT (guided and supported by World Expeditions) with her adult children. Heather is a marathon runner, and she describes the whole family as having a good fitness foundation, with plenty of hiking and bushwalking under their belts. Only her son had climbing experience, but the tour company provided training with jumars, crampons, and using fixed ropes before they hit stage two of the GHT and the high, technical passes.

“We were with climbing sherpas, and I felt very safe and well looked after,” Hawkins said.

Likewise, Jasmine Star (also guided and supported) had great base fitness before taking on the GHT. She had previously finished Bhutan’s famous Snowman Trek and had some mountaineering experience. Star managed a mountaineering lodge on Mount Hood in the 1990s and had previously climbed Mount Rainier.

“The eastern half is very hard because of all the snow,” Star said. "Sleeping, walking in snow, snow on high passes. It’s draining. The West is easier. We had three people start on the full traverse [from east to west], and one asked to be evacuated by helicopter after 27 days, which was very tricky. Different people joined for various sections of the traverse, including six people for stage two. Some suffered altitude sickness and quit to hike out to Lukla after Amphu Labsta.”

Stage two (Makalu & Everest) is the consensus crux of the route. Professional guide Soren Kruse-Ledet trekked most of the route in 1998, but from Mount Kailash in Tibet to Kangchenjunga in Eastern Nepal, and now guides sections of the GHT.

“Stage two is the most challenging as it includes Sherpani Col and West Col,” Kruse-Ledet said. "Both of them are over 6,100m, plus an additional three passes over 5,000m. It’s high altitude, remote, and technical."

He went on: "I have had situations where clients or staff have experienced altitude sickness, which can have quite a sudden onset. We’re trained and prepared to manage these situations, but we are keenly aware of the risks. But, while challenging, it is also exceptionally beautiful. You experience views of Everest and Makalu in a part of the Himalaya that doesn’t see many other travelers."

Kruse-Ledet doesn’t think the GHT is beyond most fit, outdoor people.

“I think it’s challenging because of the length of time that you’re on the route. The difficulty is not necessarily the physical aspect but the psychological challenge of having to walk nearly every day for five months. Overall, I would describe this as a difficult trek for committed and experienced walkers.”

Guide Bir Singh Gurung concurs: “Mental and physical fitness is necessary. Socially [it is different], it is a diet you are not familiar with, and comfort levels are different. You need great willpower and determination. Experienced trekkers with basic mountaineering skills are ideal.”

Vince Gayman completed the GHT guided and supported in 2018.

“I had limited mountaineering experience,” Gayman said. "I had done some glacier travel with crampons and had climbed a couple of our local peaks with ropes and an ice axe, but nothing very extensive. For someone with no experience and traveling without guides, [stage two] would be VERY challenging."

Independent vs. guided

There are several things to consider when choosing between independent and guided GHT hikes. The first may be cost.

Boustead estimates costs for independent trekkers as follows:

Go solo as much as possible: $13,500

Twin-share with minimum guiding: $7,250 per person

Solo “as much as possible” is key. Restricted Area Permits (RAPs) are required for some areas. These are for a minimum of two foreigners (making a true solo journey considerably more expensive) and require a local guide. Those completely adverse to a guide reportedly hire one to pass certain checkpoints and then release them in between. Please note that we are not advising people to do this.

At the time of writing, RAPs are required for 15 areas of Nepal: Upper Mustang, Upper Dolpo, Lower Dolpo, Tsum Valley, Manaslu Areas, Gosaikunda Municipality, Nar and Phu Trek, Khumbu Pasang Lahmu Rural Municipality Ward Five, Humla, Taplejung, Dolakha, Darchula, Sankhuwasabha, Bajhang, and Mugu.

Guided tours are, of course, much more expensive. Tour companies charge $25,000-$30,000 for a fully supported traverse (including guides, porters, accommodation, food, permits, and transport to and from the GHT).

Other things to consider include how much gear you want to/can carry, your tolerance for complex logistical planning (where to stay, how much money to carry, what permits you need, etc.), your desired pace, your fitness/alpine experience, and your route-finding abilities, particularly on the high passes and if the weather is poor.

Pace might seem a minor consideration, but larger groups move much slower, and for the speediest independent hikers, even a single guide can prove a drag.

“Some of the high passes require a fixed rope for safety,” Gayman explained. "This makes for slow going, especially with a large team carrying lots of gear. Needless to say, there is quite a bit of stop-and-go to keep everyone safe. For us, the weather was amazingly good and the views spectacular, so the pace wasn’t a problem.

Thru-hiking is a distinctly American term, but long-distance hiking routes aren’t limited to North America. The Great Himalaya Trail (GHT) might eventually encompass a continuous route through Bhutan, Nepal, and India. But for now, the Nepali GHT already offers an almighty 1,750km journey across the entire country and passes over some of the highest trekking passes in the world. Here, we examine the route and hear from those who have completed or guided the GHT.

History of the GHT

Hiking long-distance across the Nepali Himalaya is not new. Locals have covered vast distances since time immemorial, and foreign hikers have completed traverses starting in at least the 1980s.

Notable early long-distance hikers included Peter Hilary (son of Edmund Hilary) Chhewang Tashi, and Graeme Dingle walking from Sikkim, India, to the K2 Base Camp in the Karakorum in 1981, and Hugh Swift and Arlene Blum's nine-month traverse from Bhutan to Ladakh, India between 1981 and 1982.

More recently, in 1997, Frenchmen Alexandre Poussin and Sylvain Tesson hiked an impressive 5,000km in six months, from Bhutan to Tajikistan.

There have been numerous runners who’ve tackled large distances, too. Richard and Adrian Crane ran from Kanchenjunga to Nanga Parbat in 1983 and in 2023 Rosie Swale-Pope ran 1,700km across Nepal. But both of these trips deviated a long way from what is now the GHT. Swale-Pope ran in Nepal’s mid-hills, and the Crane brothers went far enough south to cross into India.

The modern GHT is a relatively new concept. Between 2008 and 2009, Robin Boustead traced a path over 162 days, linking trekking sections that became the most commonly used route.

The high route

There’s both a high and a low route through Nepal. Hikers can easily switch between them, depending on the weather and their tolerance for high-altitude passes. Often you can adapt the route to suit you. This is a network of trails rather than a singular route. But here, we’ll concentrate on one version of the high route.

Most trekking companies divide the route into three regions, East, Central, and West Nepal, and seven (or more) stages: Kangchenjunga, Makalu & Everest, Rolwaling, Langtang & Ruby Valley Link, Manaslu & Annapurna, Dolpo, and finally Nepal’s far west, Rara Lake and Yari Valley.

Hikers tend to start in the east in early March. This is a couple of weeks earlier than the typical trekking season, and it will still be cold with plenty of snow, making for a tough start.

But there is a good reason to start so early. Hikers need to complete the highest passes before the monsoon rains arrive in mid-June. This is also why most people start in the east rather than the west. The GHT’s highest, most difficult passes are bunched in the east and would potentially be more dangerous later in the year.

East Nepal: Kanchenjunga

It’s quite the slog just to get to the eastern starting point of the GHT, though it won’t tax your legs. From Kathmandu, you fly to Bhadrapur, tucked into the far south-eastern corner of Nepal on the border with West Bengal, India. From there, it’s a long drive as far north as the roads will take you to Chiruwa. The drive usually takes two long days.

After Chiruwa, you’re on foot, continuing north, parallel with the Indian border, toward Kangchenjunga in Nepal’s northeast. You start low, at around 1,600m, acclimatizing gradually as you push north. Three to four days of hiking brings you to Ghunsa (3,430m), the last village in the area that is inhabited year-round.

Over the next three days, hikers ascend quickly, climbing scree and lateral moraine to Kangchenjunga Base Camp at 5,143m. This marks the furthest east you’ll travel. Hikers then retrace their steps back to Ghunsa before the first pass of the GHT: Nango La.

At “only” 4,776m, Nango La is not terribly high, but this early in the season, it can still be tricky, with deep snow. Once over the pass, you drop over 1,000m, heading to the village of Olangchung Gola. It’s possible to do the pass and reach Olangchung Gola in one extremely long day, but most hikers choose to find a camping spot once they’ve descended the pass.

Makalu and Everest, the crux

Another reasonably complex pass, Lumbha Sambha, follows Olangchung Gola. Most people camp at a “base camp” and leave before dawn the next morning to cross the saddle of the pass at 5,160m. Expect deep snow and spectacular views of Makalu to the west and Kangchenjunga and Jannu to the east.

Once down from the pass, you’ll hike at a lower altitude for the next few days before gradually climbing toward Makalu Base Camp at 4,870m. From there, it is on to Swiss Base Camp at 5,150m.

Next comes the crux of the entire traverse: Sherpani Col and West Col.

This crossing should not be attempted in poor weather. It’s wise to take a couple of short days on approach to monitor the weather, acclimatize, and prepare your legs. The route requires crampons and ropes. Some sections require rappeling, and basic mountaineering is a plus. Few people cross Sherpani Col unguided.

It’s best to camp close to the pass. Expedition companies typically stay near the glacier's snout at 5,688m, leaving only 500m of altitude gain to Sherpani Col at 6,155m.

Sherpani Col

The ascent to Sherpani begins on a gentle snow slope but soon transitions to steep, loose rock. Once on the col, it’s a steep descent (with dangerous loose rock) requiring ropes to the flat glacier that links Sherpani and West Col (6,143m). It’s only a couple of kilometers between the cols, but in deep snow above 6,000m, it can be an energy-sapping slog.

Getting across in one day, especially for large guided groups, is rare but not impossible. Heather Hawkins, who trekked the GHT in 2016 as part of a tour, described the crossing as the hardest of her 152 days during the traverse.

“I had worried about this pass before the trip, but it was a fantastic, challenging day. It took 13 hours through deep snow and across hidden crevasse fields, but we crossed in one day. It was hard because of the altitude, and the weather deteriorated toward the end of the day, but by then, we were preparing to camp.”

Conditions are everything, and the earlier in the day you start, the firmer the snow is, and the more likely you are to cross both cols in a day.

World Expeditions, a tour company specializing in the GHT, builds in at least a day of flexibility for the crossing:

“If conditions are favorable, and the group is moving at a good pace, we may attempt both cols in a day. But in all likelihood, we’ll be camping at Baruntse Camp 1 on the West Col at 6,100m on the first night. [We then] descend the col to the Honku Valley the next day.”

The descent from West Col to the Hongku Glacier is not as steep as from Sherpani but still requires fixing ropes. From here, you’ll receive spectacular views of the Khumbu, provided the weather plays ball.

Rappelling down high passes

The next day is more relaxed, hiking across the moraines of the Hongku Basin, but it doesn’t last, the 5,000m+ passes come thick and fast till Rolwaling.

Amphu Labsta, 5,845m, is lower than the cols but a difficult glaciated pass with a narrow, exposed ridgeline. The descent requires fixed lines and rappelling. Hawkins regards this as the most technical section of the trek.

From Amphu Labsta, you descend to Chukung and then Dingboche. After some pretty remote trekking and camping, this is a return to civilization, with tea houses and (likely) many other hikers.

From Dingboche, you scramble up to cross 4,759m Cho La and then descend to the Ngozumba, the longest glacier in Nepal (the Khumbu is the largest). After crossing the glacier, you arrive in picturesque Gokyo. Here, you can take a day hike to Gokyo Ri for perhaps the best view of Everest without climbing a major peak. The trek up is brief but unrelenting, a one to three-hour slog depending on your fitness, ascending from 4,750m to 5,357m.

Whether or not you do Gokyo Ri, you’ll make a steep ascent leaving Gokyo. Renjo La (5,360m) is steep but not difficult in good weather. The descent is via huge stone steps. In good conditions, you can do the pass and descend to the village of Thame (famously, the childhood home of Tenzing Norgay and recently hit by catastrophic floods) in one long day. However, most groups either camp en route or stay in one of the tiny Sherpa villages along the way.

From Thame, there is one final big pass before Rolwaling and an extended period of lower-altitude hiking.

You can read Part II of the Great Himalayan Traverse, covering the route from Rolwaling to the Tibetan border and the differences between guided and unguided hikes, here.

This short documentary follows two young women as they bikepack along the old Arctic Post Road in Scandinavia's far north. Friends Henna Palosaari and Sami Sauri (and an unseen cameraman) set off on their mini-adventure from Yllas in Finland to Alta in Norway, hoping to knock over the roughly 430km in time for Sauri's flight back to Spain a few days later.

Their journey follows the remnants of the old Copenhagen-Alta post route and the cyclists hop between gravel tracks and mountain bike trails.

"When the gravel route goes on a road, we are not going to ride it...we both don't like riding on the road, that's the worst," Palosaari explains. "We'll go then on the mountain bike route and do a bit of a bike hike."

Rough terrain and unique snacks

The Scandinavian Arctic holds some of Europe's last true wilderness and the route to Alta isn't always easy, whether they are on the gravel or the mountain bike trails. At times, the bike-packing is literal: Rocky, uphill sections force the pair to shoulder their bikes and carry them to easier ground. There are streams to ford and muddy trails to struggle through. The crossing from Finland to Norway is particularly rustic and involves creating a hole in a barbed wire fence and squeezing through.

Villages are few and far between, but when they do run into people, they make the most of it, trying some reindeer tongue and getting some piping hot food.

They arrive in Alta with time to spare for a final "dinner" of bread and cheese.

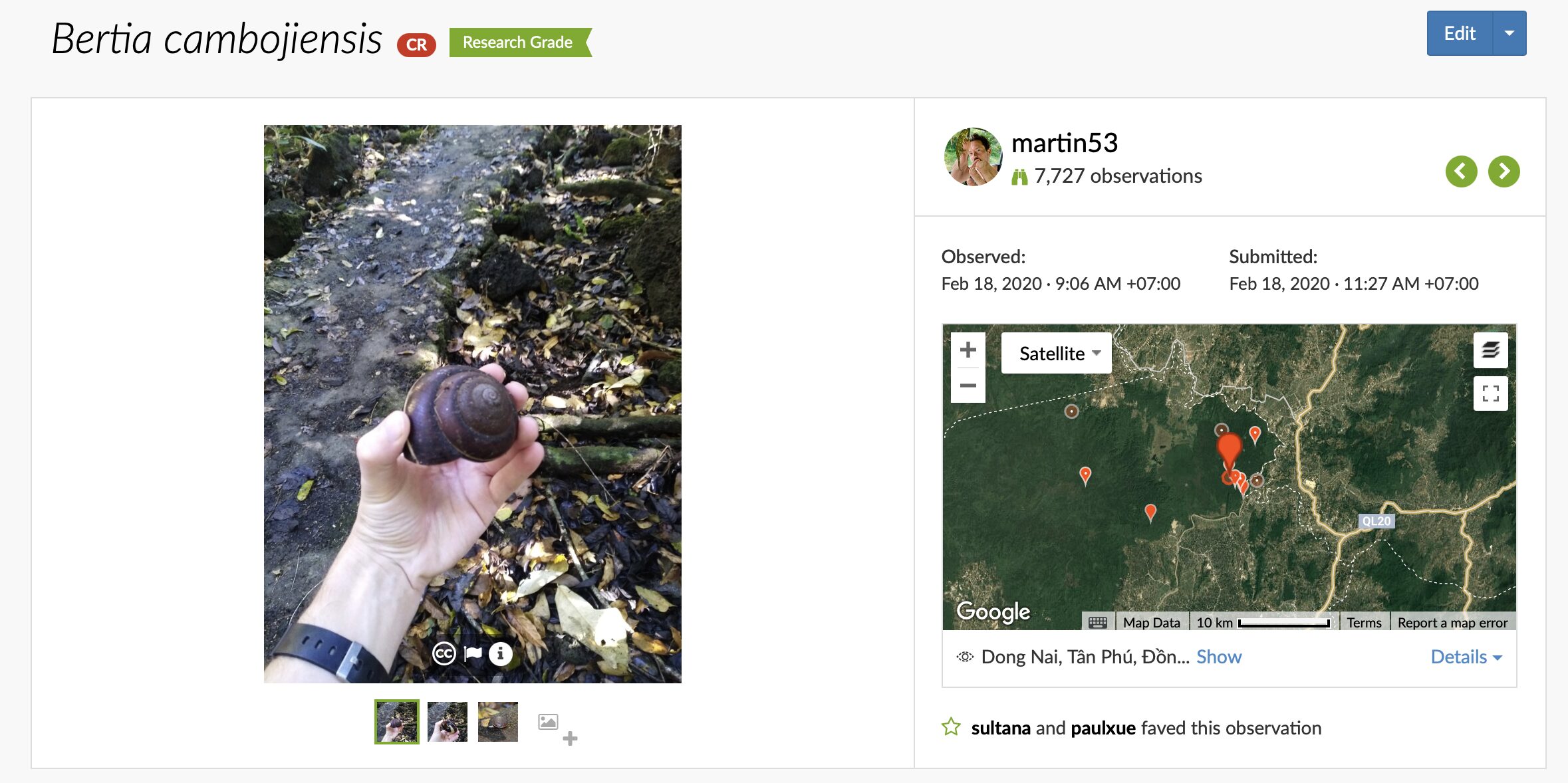

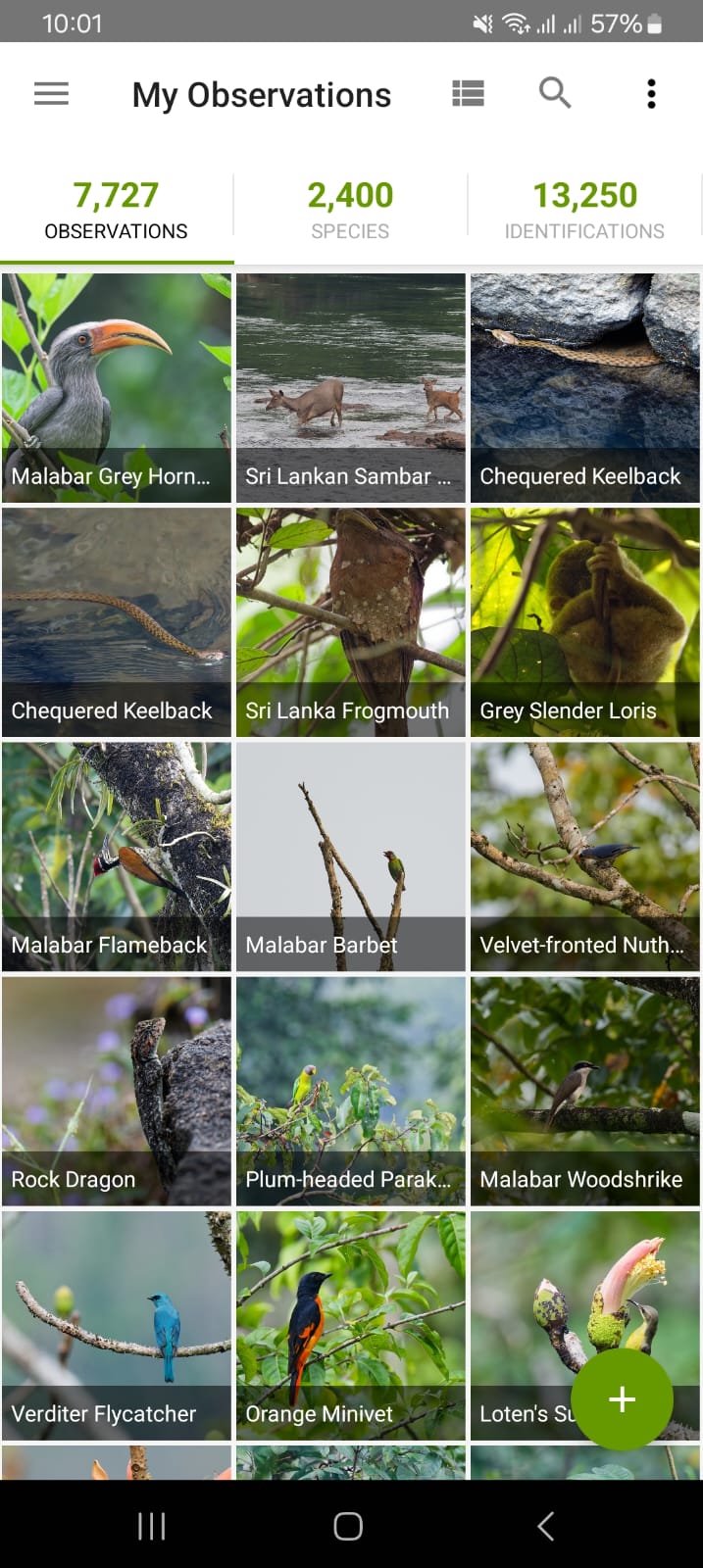

I started using iNaturalist in 2018. I had been using the app, a free citizen science platform that defies easy categorization, to record the wildlife I observed as I traveled. A sort of real-life Pokemon. But it wasn't until 2020 that I was fully hooked.

I was walking through Cat Tien, a sweaty chunk of lowland jungle in Vietnam. I had spent the night at a ranger station set up to protect a critically endangered population of Siamese crocodiles. But it wasn't the crocodiles that triggered my iNat addiction. It was something much smaller, something I might not have noticed pre-iNat, let alone photographed. On the trail, I found a large land snail and decided to take a couple of snaps of it.

Later, I uploaded the sighting to iNaturalist. For some organisms, the AI identification tool immediately provides an ID with reasonable certainty. For others, it has less information to work with. In these cases, you upload with an ID to whatever level you're comfortable with. With no knowledge of Vietnamese snail species, I went with the very generic gastropods.

More than a social network

This is when another of iNat's functions comes in. The app (and website) do much more than serve as a gallery of the things you've seen. It describes itself as "an online social network of people sharing biodiversity information to help each other learn about nature. It's also a crowdsourced species identification system and an organism occurrence recording tool."

Within a couple of days, other users identified my snail as Bertia cambojiensis, the Vietnamese giant magnolia snail. Critically endangered, this species was long thought extinct and only rediscovered in 2012.

From there, it was a slippery slope. Within a year, I'd bought a large camera and some proper binoculars. Soon, I was reading research papers on species splits and primate behavioral studies. Last week, I was chatting to a lepidopterist (someone who studies moths/butterflies) in Colombia who wanted to know if she could use one of my photos for a field guide. I'm 2,400 species deep and still going strong.

And that's the thing: iNaturalist makes you look at the world differently. It encourages you to take in what's around you, to explore, and to learn about what you find. Unlike eBird, which has been around much longer and also collects crowd-sourced data, iNat deals with all life: plants, birds, mammals, reptiles, viruses -- if it is wild, upload it. This breadth encourages learning, and it encourages a more holistic view of the natural world.

Fancy getting addicted, too? Here's a quick explainer on how to use iNaturalist.

Getting started

It might be helpful to think of the three elements of iNaturalist as different levels of interest.

Do you just want a quick AI-driven ID of something in your garden? Try the Seek app, made by the same company. This is the most basic version of what iNaturalist offers. Point your phone at a flower, take a photo, and the image recognition software will try to tell you what it is. You don't have to upload the observation (but you can!).

Want to track what you've seen and contribute to science? Then, the iNaturalist app is better for you. It will track what you've uploaded, allow you to explore other people's observations from around the world, and provides most of the functionality of the website. You can find the Android app here and the iPhone app here.

Want the full package? The website is best if you want to do all of the above and also help others to identify their observations. I use it to learn, plan trips, and help out by identifying birds and mammals in Southeast Asia, where fewer users have the requisite knowledge.

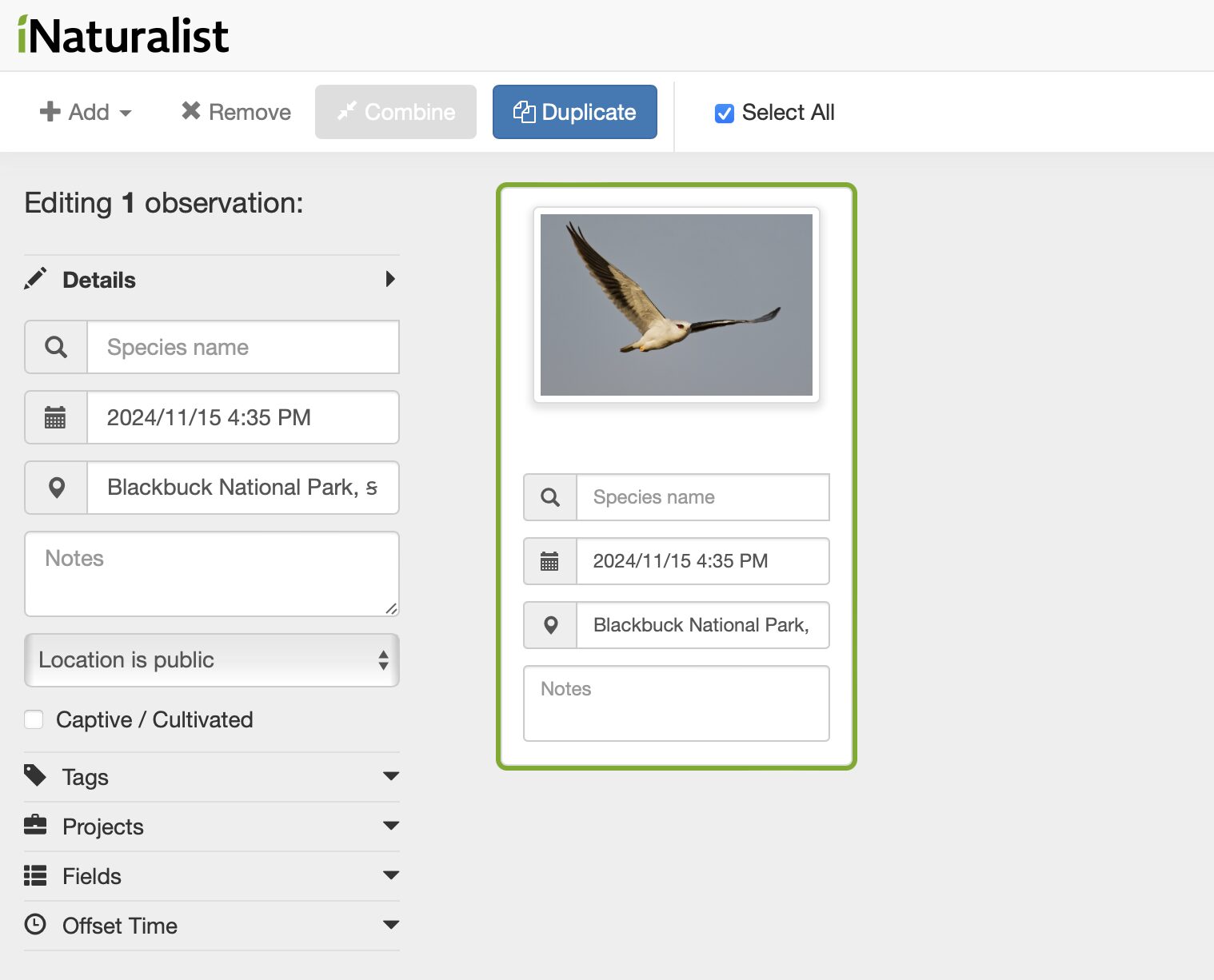

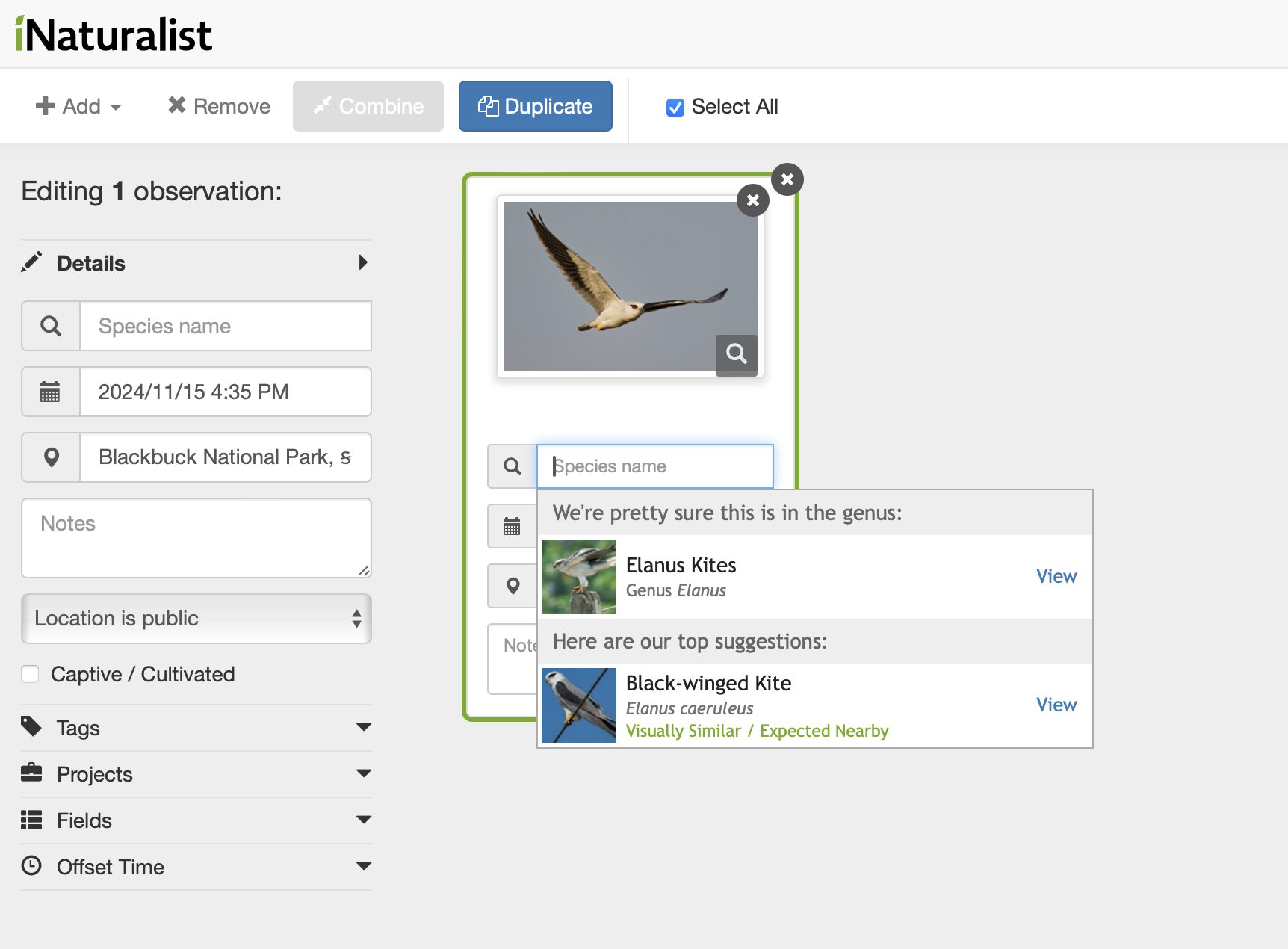

Making an observation

To make an observation, you need a few things.

- A photo or a sound recording.

- When (date/time) you saw the organism. This is usually added automatically from a photo's metadata.

- Where you saw the organism. This can be added automatically if you're taking the photo on your phone. Otherwise, you will need to do this manually using the map.

- What did you see? The AI will offer suggestions. Sometimes, it will say: "We're pretty sure this is..." with a single suggestion. If this matches what you observed, select this. Other times, it won't be so sure: "Here are our top suggestions." In this case, it is best to only ID to a level you are sure of -- eg. You've seen a woodpecker but you're not sure of the species? Type in woodpeckers and select the family group. It's always better to go with a coarse ID like "Birds" or "Mammals" rather than guess what something is.

- Was it wild? Is it a pet/zoo animal/cultivated plant? Then tick the captive/cultivated box.

Got old wildlife photos? You can upload historical records, too.

iNaturalist has a detailed step-by-step guide to making observations here.

Citizen science

If an observation reaches "Research Grade" (has all the data listed above and the ID is agreed upon by at least 2/3 of identifiers), then scientists can use it. You might see your observations included in a research paper or upcoming study.

Occasionally, iNaturalist leads to the rediscovery of a species or the discovery of new ones. This month, a London commuter uploaded an invasive insect not seen in the UK for 18 years. Last month, a marine worm was rediscovered after 68 years when researchers spotted it photobombing seahorses, and a user spotted a humpback whale in New York's East River!

During the pandemic, bitcoin millionaire Jon Collins-Black devised a grand treasure hunt. Over the next few years, he amassed two million dollars of valuables, including gold, a Michael Jordan rookie card, lunar rock specimens, and a coin designed and minted by Pablo Picasso. He then hid the loot in five chests across the U.S. and is releasing a book of clues to help treasure hunters find them.

The book, There’s Treasure Inside, features puzzles and maps. Collins-Black released it earlier this month.

"You don’t have to be a genius to solve the clues. There’s no grand cipher. If you have curiosity, imagination, and the willingness to try something new, you can find the treasures that I’ve hidden," Collins-Black announced.

Somewhere in the open

According to Collins-Black, all five chests are within three miles of a public road and are not buried. None are on private land.

This is not a new concept. The genre is known as "armchair treasure hunts" and perhaps started with Kit Williams' 1979 picture book Masquerade. The book featured 15 painted illustrations that concealed an elaborate puzzle. Alongside the book, Williams crafted and then buried a jeweled, golden hare.

Masquerade was solved three years later, but it turned out that the "winner" had used insider knowledge to tip the scales, causing some controversy. It will be interesting to see if Collins-Black's effort lasts as long.

The Banff Mountain Book Competition has released its 2024 award winners, offering readers a curated list of great new adventure and mountain exploration books.

Each year, the competition awards $29,000 in cash prizes across eight categories: Mountain Literature (Non-Fiction), Mountain Fiction and Poetry, Environmental Literature, Adventure Travel, Mountain Image, Guidebook, Mountain Article, and Climbing Literature.

You can see the winners of those categories below, but you’ll have to wait until October 31 to find out the Grand Prize winner, which will be announced at the Banff Centre Mountain Film and Book Festival.

Adventure Travel

Move Like Water: My Story of the Sea

Hannah Stowe, Tin House (USA, 2023)

"The visceral power of the sea and its hold on all who immerse themselves in its world are conjured with wonder in this beautifully written memoir. Exploring it through her own remarkable story as a mariner and marine biologist and sharing with us hardships, dangers, and accidents, but above all, her passion for the sea, Hannah Stowe shows us a seascape we might think we know but don’t. Featuring such emblematic sea creatures as the whale, the albatross, and the humble but extraordinary barnacle, this is a siren song in vivid, exacting prose."

- Tony Whittome, 2024 Book Competition Jury

Mountain Fiction & Poetry

Empty Spaces

Jordan Abel, McClelland & Stewart (Canada, 2023)

"Empty Spaces, by Nisga’aa writer Jordan Abel, is a book of poetry that does not behave like most poetry. It is a flowing river of words that represent the timelessness, power, and movement of the natural world. Reading this book is like entering a deep forest and feeling the wind, hearing birdsong. There is a haunting progression through the ages, followed by the arrival of cities, violence, towers, garbage, and bodies. Until the natural world re-emerges. At once harrowing and consoling, Empty Spaces gives us a profound experience of the land that rewrites our history."

- Marni Jackson, 2024 Book Competition Jury

Mountain Literature (Non-Fiction), The John Whyte Award

Alpine Rising: Sherpas, Baltis, and the Triumph of Local Climbers in the Greater Ranges

Bernadette McDonald, Mountaineers Books (USA, 2024)

"We are privileged as judges to honor not one but two books that help transform our understanding of Himalayan mountaineering. Bernadette McDonald’s Alpine Rising, arguably the most important book in her long and distinguished career, tells the unsung, heroic, and sometimes tragic story of the Sherpas, the Baltis, and other Indigenous peoples without whom no Himalayan peak could have been climbed. As truths emerge from the shadows of empire and they take their rightful place in their world, she reveals the lives and humanity behind their dramatic stories, culminating in the all-Nepali first winter ascent of K2."

- Tony Whittome, 2024 Book Competition Jury

Environmental Literature

Crossings: How Road Ecology Is Shaping the Future of Our Planet

Ben Goldfarb, W.W. Norton & Company (USA, 2023)

"A million animals a year are killed by cars in the U.S. alone, even though environmentalists are building highways for mountain lions and bridges for toads. The Banff underpass also has a cameo in this stunning work of reportage. Ben Goldfarb somehow makes a book about roadkill and asphalt into a reading experience that will forever change how you view the environment. Crossings is full of humor, memorable characters, and lively writing on a topic that could not be more important to the health of the planet."

- Marni Jackson, 2024 Book Competition Jury

Mountain Image

Monica Dalmasso: Sauvage!

Monica Dalmasso and Cédric Sapin-Defour, Glenat (France, 2023)

"It is fascinating to see how each person interprets art differently. Are we meant to take in a book from cover to cover, or do individual images resonate more when absorbed gradually over time? Is simplicity or complexity more important? That's the nature of art; it gets us all talking. Sauvage! was chosen as this year’s Mountain Image winner for its diverse portrayal of mountain life, showcasing everything from the presence of humanity within its landscapes to its absence, as well as the macro details that define these elevated terrains. Although the text was not meant to be weighed as heavily as the imagery, I found the words in Sauvage! perfectly complemented the visuals in a way that enhanced and added depth to the imagery, making me continually want to turn pages. In the end, we all agreed: this book inspired us to want to go out, explore the world, and create a few images of our own. And if that's not the purpose of mountain imagery, then what is?"

- Irene Yee, 2024 Photo Competition Jury

Guidebook

Backpacking on Vancouver Island: The Essential Guide to the Best Multi-Day Trips and Day Hikes

Taryn Eyton, Greystone Books (Canada, 2024)

"Taryn Eaton’s approach to traversing the forested expanses of Vancouver Island is practical, portable, and inspiring. Her helpful and vivid descriptions of some of the region’s best treks leave readers dreaming up their next adventure through the island’s towering cedars and whispering inlets — or reveling in journeys past. With compelling writing and a leave-no-trace ethos, this guide is sure to stand the test of time as the perfect companion on any hike through the island’s rugged mountains or along rain-drenched coasts."

- Gloria Dickie, 2024 Book Competition Jury

Mountain Article

The Terror of Turning a Corner

Astra Lincoln, Climbing Magazine (USA, 2024)

"If you’ve ever suffered a concussion, you may know that recovery can take a surprisingly long time, and it can shake your confidence too. This is what happened to climber Astra Lincoln after a bike accident left her with lingering post-concussion symptoms. In this buoyant and highly entertaining article, Astra Lincoln describes how coming back to climbing on a modest route in Colombia brought her face to face with her post-injury fears and led her to acceptance."

- Marni Jackson, 2024 Book Competition Jury

Climbing Literature

Headstrap: Legends and Lore from the Climbing Sherpas of Darjeeling

Nandini Purandare and Deepa Balsavar, Mountaineers Books (USA, 2024)

"A phenomenal feat of oral history that sheds light on the historically overlooked role of Darjeeling Sherpas in developing the mountain exploration and climbing culture that has come to define the Himalayan region. Recognizing their valor and strength of spirit, body, and mind, Headstrap gives these awe-inspiring figures their due. Purandare and Balsavar have made a pivotal contribution to the realm of climbing literature with this painstakingly researched and passionately curated book."

- Gloria Dickie, 2024 Book Competition Jury

Most visitors don’t consider the Himalaya a wildlife destination, but the world’s highest mountains hold a surprising amount of diversity.

From snow leopards and grumpy Pallas's cats to blood pheasants and red pandas, here are some of the places wildlife watchers head for mountain wildlife.

Hemis National Park, Ladakh, India

Hemis covers 4,400 square kilometers a vast swathe of rugged, high-altitude desert between 3,000 and 6,000m in Ladakh, India.

The park holds a stable population of argali, urial, and bharal (all wild sheep species). These are nice to spot, but for most visitors, they are more important for what they represent: big cat food. An abundance of prey supports an estimated 200 snow leopards in Hemis, which might be the highest density of any protected area in the world.

For a long time, wildlife watchers regarded seeing a wild snow leopard as almost impossible. Evidence of their presence (scat, territorial markings, paw prints) was easy enough to find, but actually spotting the ghost of the Himalaya was a tall task. Sightings required insane luck or months, if not years, of work.

Now, things are much easier. Increased knowledge of territories and habits revealed that snow leopard sightings were not just possible but likely, given enough time. You needed to be in the right place at the right time. And you will need to spend long hours in the cold.

Sightings generally require at least a few days spent scouring ridges and cliff faces at dawn and dusk. It’s cold, uncomfortable work, but the potential payoff for photographers and wildlife enthusiasts is worth the effort.

And sightings aren’t restricted to big national parks like Hemis. In remote Ladakhi villages, residents will tell you that they regularly see the cats. Locals have shown me phone camera videos of snow leopards practically close enough to touch, stalking past houses and leaping dry-stone walls (and occasionally taking domestic livestock -- leading to some human-wildlife conflict). As a result, some of these out-of-the-way hamlets now draw tourists for week-long stays.

Eagle’s Nest, Arunachal Pradesh, India

Foreigners require special permission to visit Eagle’s Nest in Arunachal Pradesh. This means it’s not a cheap trip, despite only basic accommodation at two campsites. However, it continues to attract adventurous wildlife enthusiasts because the area has built a strong reputation for unusual wildlife sightings.

Named after an old military base (formally occupied by the “Eagles” unit), the area is particularly popular with birders. In 2006, researchers described a new species of liocichla from here. Ornithologists named it the Bugun liocichla after a local ethnic group. With evidence of only 10 breeding pairs, it is critically endangered.

Though it has long been a birding destination, it has only recently caught the attention of mammal watchers. The road between the two campsites has proved productive for some hard-to-see nocturnal species, including mega-rarities like clouded leopards and golden cats.

Sagarmatha National Park, Nepal

More than just Everest, Sagarmatha National Park is surprisingly busy with wildlife. Despite the heavy foot traffic during trekking and climbing season, you can see many pheasant and grouse species, including blood pheasants and the national bird of Nepal, the monal. Commonly seen mammals include Himalayan musk deer and Himalayan tahr.

Humans wiped out snow leopards here in the 1970s through overhunting, both of the cats and their prey. A small number have returned over the last half century as the prey species have rebounded. However, sightings remain extremely scarce.

Langtang National Park, Nepal

Established in 1976, Langtang was the first-ever Himalayan National Park. Its proximity to Kathmandu (it starts just 30km from the capital and stretches to the China-Tibet border) makes it easy to visit independently.

It has a reputation as a good spot to find red pandas and is fantastic for birds (373 species recorded) because of lakes such as Gosainkunda. Commonly observed mammals include Himalayan tahr, Himalayan musk deer, Assam macaque, and Nepal sacred langur.

While most wildlife-focused visitors to Nepal head to Chitwan National Park or Bardiya National Park down in the Terai, it’s worth combining a visit with some hiking to look for mountain specialist species.

Hengduan Mountains and the Tibetan/Himalayan Plateau, China

Though they are not technically the Himalaya, I’m lumping the Hengduan mountains of Sichuan and neighboring areas of the Tibetan Plateau into this list.

This is one of the best regions in the world to see an array of cat species. Pallas’s cat (the manul), Eurasian lynx, snow leopard, Chinese mountain cat, and leopard are all possible here. Asian brown bears and wolves are not uncommon. Tantalizingly, it is also one of the few places where you might spot a wild panda.

National parks are a new concept in China. The government revealed five initial national parks in 2021. One of these was Giant Panda National Park, an effort to unite a sprawling group of 81 existing nature reserves. Tangjiahe Nature Reserve in the Hengduan Mountains is part of the park's core area. The elevation ranges from 1,150m to 3,837m and features a mix of dense bamboo and subtropical forest. It is an important panda habitat.

Sightings are extremely difficult, and those who do spot a wild panda are reluctant to reveal exactly where sightings took place. Researchers estimate that there are 39 pandas in the reserve.

Other charismatic megafauna present include golden snub-nosed monkeys and Tibetan takin, a species of goat-antelope.

The potentially life-sapping cold of continental Siberia requires a specific lifestyle. In Yakutia, the world's largest administrative and territorial region, people must adapt to long, brutal winters with average temperatures of -50°C. The lowest temperature recorded was -71°C, the coldest on Earth outside Antarctica.

Keep busy, keep warm

This short documentary gives a snapshot of family life in this harsh environment.

Yakutia is not a place to be lazy; everyone pulls their weight. Simple things like drinking water take preparation and effort. There are no water treatment facilities here, since the pipes can't stand the cold. So water is harvested from a local stream in November and then piled up in big blocks of ice outside the house to melt as required.

Families have to heat their houses for nine months a year, so collecting and chopping firewood is another essential daily task. Fishing and hunting are almost equally vital.

Arian is just nine years old, but he might already have more (and better) practical skills than I do. He descales and guts fish with his mother, goes ice fishing with his father, and chops wood for the fire with a not insignificantly-sized axe.

"I believe every single man has to be able to make something by hand," Arian's knife-crafting father says. "At least knives or dishes."

'Snow days' are rare

When it's "warm" enough, Arian gets a break to go to school. The children in Yakutia only go to school when it’s warmer than -54°C. If it is any colder, the government considers it too dangerous to venture outside.

But on this day, it's a balmy -40°C, and Arian gets kitted up for a mini-polar expedition -- the 10-minute walk to his classroom. He seems a chipper kid, unfazed by what most people would consider life-threatening conditions. During this short 20-minute watch, Arian and his family seem happy. Their lifestyle looks almost idyllic if you don't think about it too hard.

"There is no such thing as bad weather, there is just weather and your attitude toward it," the narrator says, borrowing a quote from American self-help author Louise Hay to wrap up the video. It's a nice sentiment. However, I doubt Hay ever had the runs while it was -71°C, and the only toilet was outside and unheated.

Polar bears aren't native to Iceland, though an occasional vagrant arrives from Greenland. So, it was quite a surprise for an elderly resident of a remote village to find one raiding her bins. Panicked, she locked herself upstairs and called for help.

After consulting with the Icelandic Environment Agency, police arrived and shot the bear. The agency decided not to try and relocate the animal, following recommendations laid out in a 2008 study. That study concluded that moving bears back to Greenland was prohibitively expensive and suggested killing vagrant bears was the best response.

A protected species?

Polar bears are a protected species in Iceland and cannot be killed at sea. However, they can be killed if they threaten humans or livestock.

"It’s not something we like to do," Westfjords Police Chief Helgi Jensson told The Associated Press. "The bear was very close to a summer house. There was an old woman in there."

This is the first polar bear sighting in Iceland since 2016. Only 600 polar bears have been recorded in Iceland since the ninth century. Experts believe this bear may have traveled from eastern Greenland on an iceberg, of which several were spotted near the north coast recently.

Wildlife photography is as much about luck as skill, but you have to take your opportunities. Photographer Tomis Filipovic certainly made the most of his.

While photographing whales, Filipovic caught a once-in-a-lifetime moment in the Strait of Juan de Fuca near Vancouver Island, Canada. A feeding humpback whale accidentally caught a harbor seal in its mouth, spitting out the undoubtedly confused seal soon after.

"Luckily, a humpback's throat is only about as wide as a grapefruit, so it can't take in anything bigger than that," Filipovic told CTV News in an interview.

Filipovic wasn't the only observer to capture the moment. Brooke Casanova with Blue Kingdom Whale & Wildlife Tours also landed a shot of the rare encounter.

From stuffing pigeons into missiles to discovering that animals can breathe through their anuses, the 2024 Ig Nobel Prize awards have no shortage of headline-grabbing studies.

The ignoble Nobel prize

The Ig Nobel Prize started in 1991 and aims to "honor achievements that first make people laugh, and then make them think." Though it is a riff on the Nobel Prize, the "ignoble" prize does recognize genuine achievements, though without the life-changing million-dollar reward. Instead, winners are given a one-trillion Zimbabwean dollar banknote, worth less than one U.S. dollar.

This year there are 10 studies recognized in 10 categories.

A team of Japanese scientists won the Ig Nobel Prize in physiology for a study that showed that mice, rats, and pigs could absorb oxygen into the bloodstream via the rectum. At first blush, this might not sound like a particularly useful discovery, however, researchers hope that "enteral ventilation" could help treat human patients with respiratory failure. The team is now running a phase one trial with human volunteers.

The Peace Prize went to the late BF Skinner, a U.S. psychologist. His study explored placing live pigeons in missiles to guide them to their targets.

"This is the history of a crackpot idea, born on the wrong side of the tracks intellectually speaking, but eventually vindicated in a sort of middle-class respectability. It is the story of a proposal to use living organisms to guide missiles," Skinner wrote by way of introduction to his article Pigeons in a Pelican.

Can we trust reports of extreme old age?

Saul Newman at the University of Oxford won the Demography Prize for his study looking into claims of extreme old age. Newman demonstrated that many claims of extreme old age in humans come with a host of suspect data points.

"Relative poverty and short lifespan constitute unexpected predictors of centenarian [100 years] and supercentenarian [110 years] status and support a primary role of fraud and error in generating remarkable human age records," the study concludes. "Only 18% of ‘exhaustively’ validated supercentenarians have a birth certificate, falling to zero percent in the USA."

The Medicine Award went to a mixed Swiss/German/Belgian team for their study that involved a (rather terrifying) twist on the placebo effect. Researchers found that medicine that causes side effects can be more effective than medicine that does not.

The Chemistry award went to a Dutch team that separated drunk worms from their sober brethren using chromatography (separating a mixture into its components) and a maze. The study aims to increase our understanding of polymer dynamics by analyzing differences in wriggle activity.

"The sad conclusion is that the drunk worms get home very late," Woutersen said as he accepted the award.

Plant vision and the swimming abilities of dead trout

American Jacob White and German Felipe Yamashita shared the Botany Award for their potential discovery of "plant vision." The duo found that a South American plant can mimic the leaves of plastic plants it is placed next to.

Physics went to James Liao from the University of Florida for an off-the-wall-sounding study that investigated the swimming abilities of a dead trout.

"The musculoskeletal system [of trout] is phenomenally well matched to the environment. We know this because a dead fish exhibits unnervingly similar Karman gait kinematics [an undulatory swimming motion] to a live fish, with the exception that it cannot put on the brakes. In a remarkable example of passive thrust production," the study explained.

Winning coin flips and scaring cows with cats

Fifty researchers shared the Probability Prize for their study on the good old coin flip. After over 350,000 coin flips, their study concluded that coins are marginally more likely to land the same way up as they started.

Finally, Fordyce Ely and William Petersen won the Biology Award posthumously for their investigation into dairy milk production. They decided to scare cows using a cat and exploding paper bags to see what would happen to the cow's milk. Perhaps unsurprisingly, cows harassed by a cat on their back and subject to exploding bags produced less milk.

In an extremely unusual situation, a golden eagle was killed after a string of attacks in Norway. The bird attacked four people, including a toddler.

Golden eagles are a widely distributed species with an average wingspan of around 2m. Though intimidatingly large birds, golden eagles usually hunt small prey, such as rabbits and marmots. Attacks on humans are practically unheard of. Yet, over a few days last week, a young eagle showed behavior that was "radically different from normal."

A brazen attack

The most recent (and final) attack may have been the most terrifying. The eagle grabbed a 20-month-old toddler while she was playing in her garden in Norway's central Trondelag region. Fortunately, her mother and a neighbor were nearby. It took both adults to force the eagle to release the toddler, who needed stitches and was left with scratches on her face.

"But it kept coming back," the child's father told Norwegian public broadcaster NRK. It was undeterred even when "the neighbor chased it away with a stick."

The incident with the toddler appears to have been the fourth attack. Two days previously, 31-year-old Francis Ari Sture was out hiking when he thought a human had tried to shove him from a cliff. Turning to confront his attacker he came face to face with an extremely aggressive golden eagle.

"We are staring at each other for, maybe, a whole minute," Sture told the Associated Press. Then, the eagle launched a barrage of attacks, chasing him down the mountain and scratching at his head and face. Sture managed to escape and a local hospital treated him for deep wounds to his face.

An eagle with a behavioral disorder

A day before that, the eagle attacked Mariann Myrvang. The eagle landed on her shoulders, forcing her to her knees under its weight. Myrvang's husband had to beat it with a tree branch to drive it away. Like Sture, Myrvang required a hospital visit.

Alv Ottar Folkestad from BirdLife Norge believes that the young female eagle must have had a "behavioral disorder," that prompted the highly unusual sequence of attacks.

Whatever the cause, the bizarre reign of terror is now over. Local game warden Per Kare Vinterdal arrived shortly after the attack on the toddler and killed the eagle.

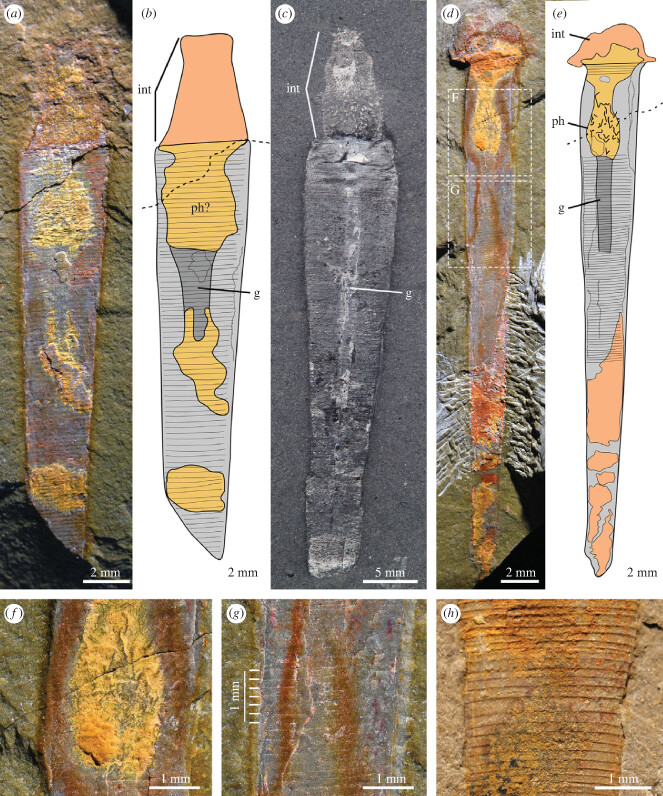

Three tiny glass beads, from a sample of 3,000 taken from the Moon, have revealed evidence of recent volcanic activity. Previous scientific estimates suggested volcanic activity ended more than 2 billion years ago, but a new study suggests far, far more recent eruptions. Volcanoes on our lunar satellite were still spewing lava while dinosaurs walked the Earth.

Valuable cargo

The samples, picked up by the Chinese Chang'e 5 mission in 2020, are the first Moon rocks brought to Earth since the 1970s. Over the next four years, a team from the Institute of Geology and Geophysics at the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing painstakingly analyzed the minute beads, each smaller than a pinhead. On Sept. 5, they published their findings.

They only identified three beads with a volcanic origin "based on their textures, chemical compositions, and sulfur isotopes." The remaining 2,997 were likely the result of meteorite impacts.

Though these aren't the first volcanic beads discovered on the Moon, they are certainly the most interesting. Previous samples date back billions of years, to the formation of lunar maria, enormous basaltic plains formed by lava flowing into craters. Meanwhile, "uranium-lead dating of the three volcanic glass beads [from 2020] shows that they formed 123 million, ±15 million, years ago," the report explains.

What was driving volcanic activity for so long?

However, existing models of the Moon's evolution suggest that its interior should have cooled beyond volcanism long before the formation of these glass beads.

As is often the case, researchers are left with more questions than answers. Perhaps the recently discovered Moon cave will help scientists understand what caused this surprisingly recent volcanic activity...

In a trend that is unlikely to abate any time soon, people engrossed in their mobile phones risked their lives for content. A viral video from China shows tourists caught out by surging waters on the Qiantang River.

The Qiantang River flows through the Chinese province of Zhejiang on the eastern coast, just below Shanghai. The video of tourists on the river's edge, posted on X, is allegedly from a couple of days ago. Though we can't confirm the video's authenticity, it appears to show a huge tidal bore rushing up the river and then engulfing a group of around 20 people filming or photographing the incoming wave. The water sweeps some people away and it isn't immediately apparent if everyone is accounted for as the water recedes.

The video, with a warning that the content could be distressing, can be viewed below.

WARNING - disturbing (And I post this as a warning).

Another video of people taking dangerous selfies. This is Qiantang River in China a couple of days ago....

pic.twitter.com/0P5JhX2FTH

— Volcaholic

(@volcaholic1) September 8, 2024

The surge could be because of typhoon Yagi, a superstorm that has left a trail of destruction in its wake across the Philippines, south-eastern China, and north Vietnam. Asia's largest storm of the year, Yagi has killed at least 141 people in Vietnam.

Unnecessary risks?

This is not the first phone-related death we've covered this summer. In mid-August, Czech gymnast Natalie Stichova fell to her death in Germany while trying to get in position for an Instagram photo with the famous Neuschwanstein Castle.

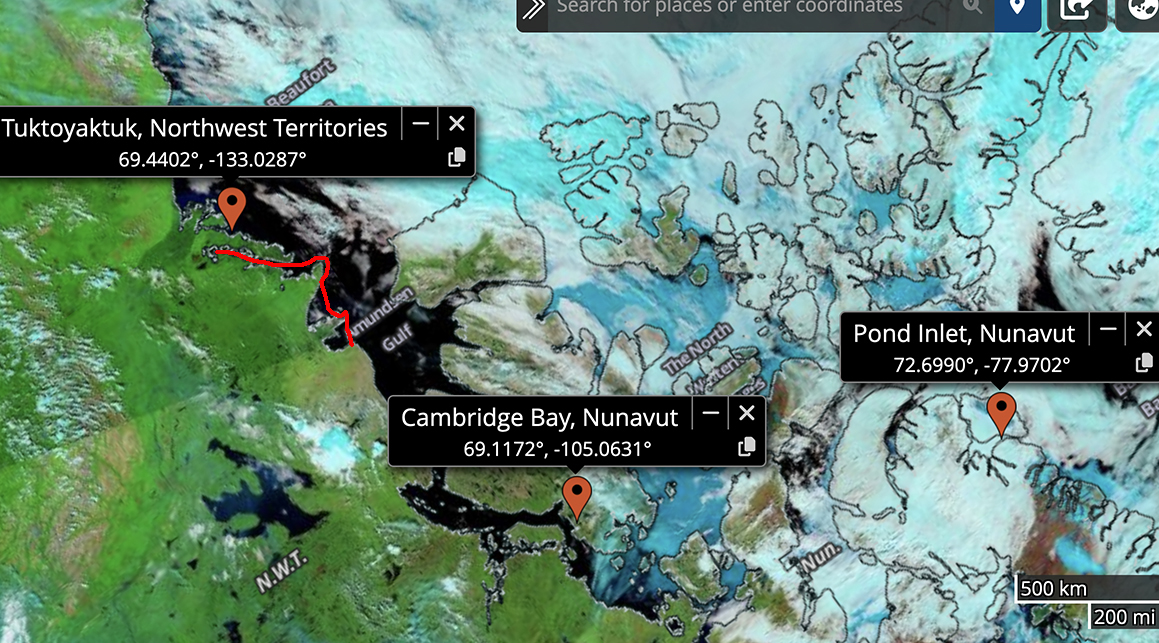

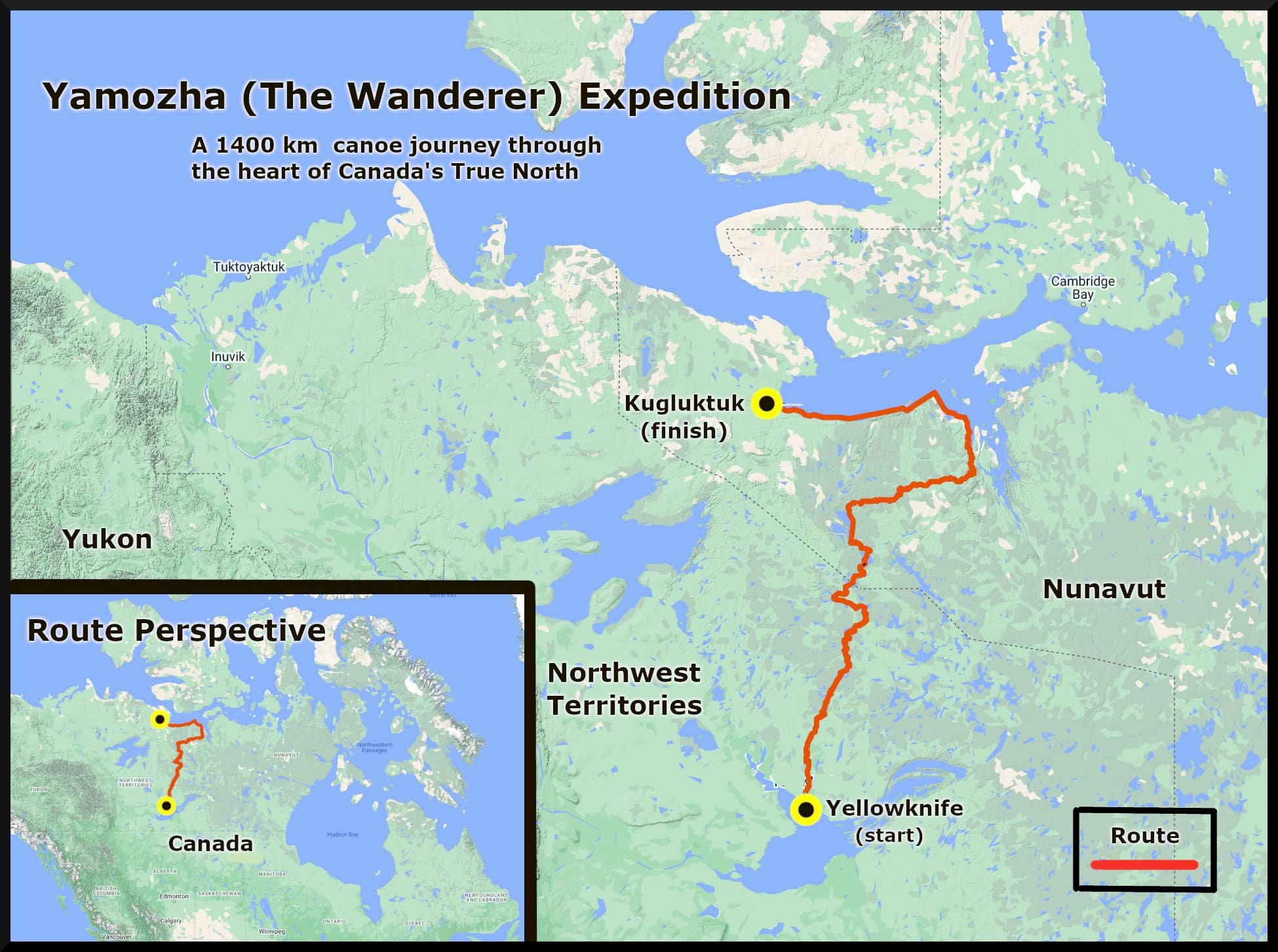

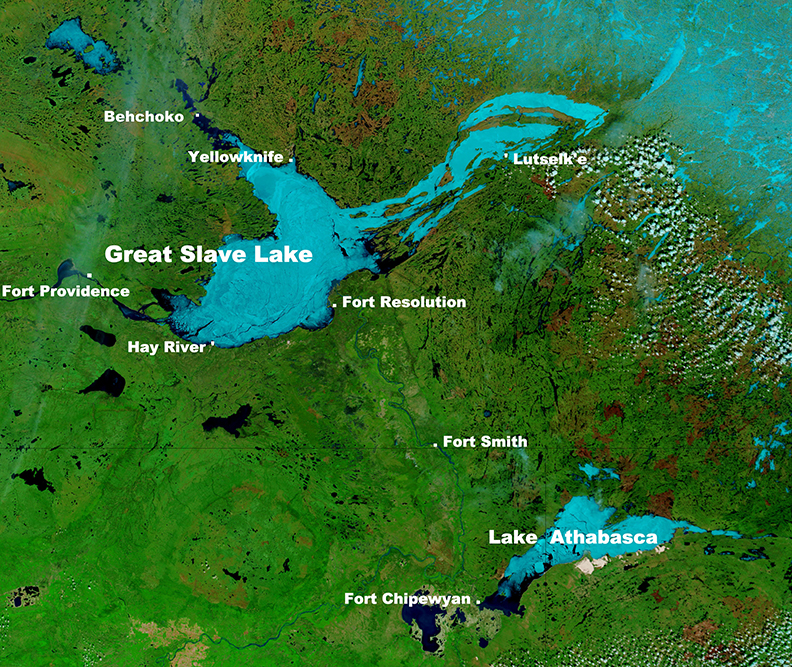

After 140 days split between cycling, canoeing, sailing, and hiking, the Canada west-to-east team has finished their 6,900km crossing of Canada's north.

Nicolas Roulx and Catherine Chagnon set out from Beaver Creek on the Alaska-Yukon border on April 21. They started on bicycles for a 16-day "warm up" as they pedaled east on the Alaska Highway. After a nasty climbing accident shortly after his 2021 Canada north-to-south expedition, Roulx hoped that the relatively relaxed start would help ease him into a long, physical journey.

The ride went smoothly, with "some knee pain, but nothing serious or abnormal," before the real test began on the wild rivers of the Northwest Territories and Nunavut.

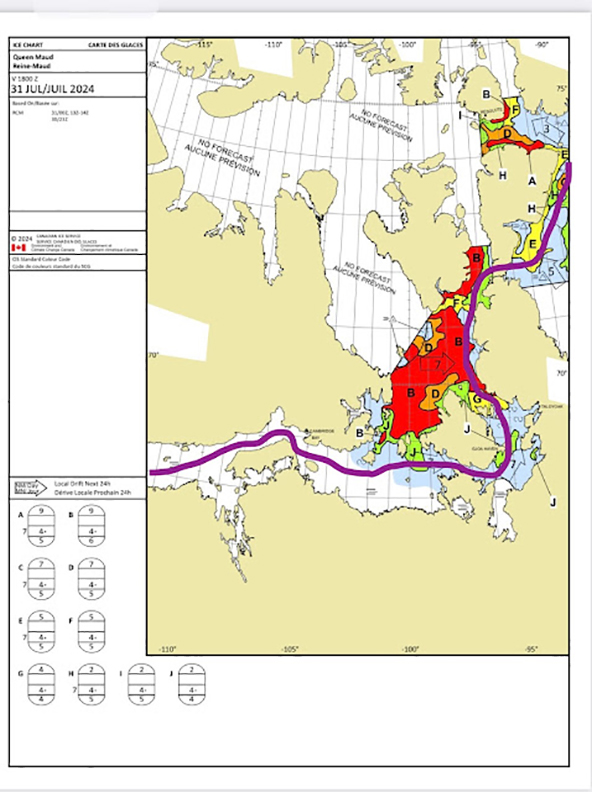

A battle against the clock