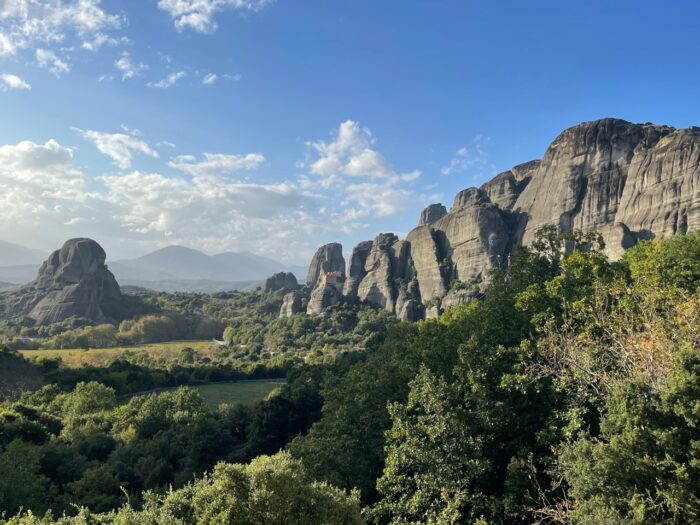

Meteora is a complex of imposing dark rocks, rising over the settlements of Kalampaka and the picturesque Kastraki village, on the plain of Thessaly, Greece. There are approximately 900 multi-pitch climbing routes in the Meteora towers. The texture of the rocks, the fairytale setting, and the fact that every route ends at the top of an outstanding tower make climbing in Meteora a peculiar experience.

Meteora's rocks and climbing style

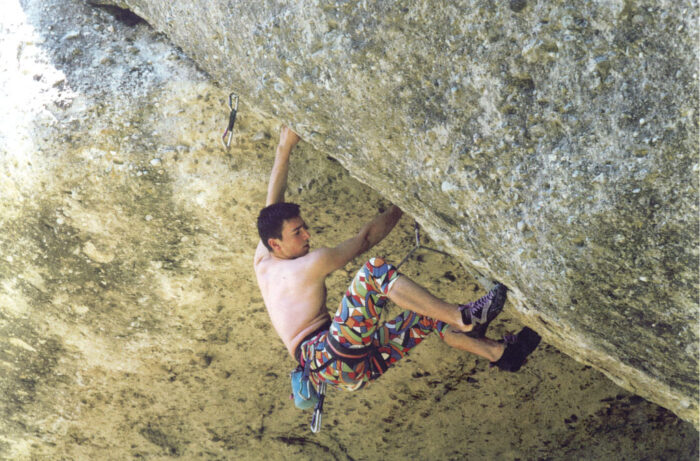

Meteora's rock texture consists of a combination of pebbles, cobbles, and large rocks attached to a cement-like sandstone and cobblestone rock surface. Shallow holes are often encountered as a result of pebble detachment. When first climbing here, the texture can make the rock feel unstable, especially on downhill pebbles. But gradually, you will learn that the rock is stable.

The slope and the size of the pebbles determine the grade of the routes. Most of the routes are balanced, emphasize technique, and include delicate movements without the need for particularly athletic skills. High grades are considered exceptions. The main traits of the routes are their mixture of slab-based trad and sport climbing.

A look back in time

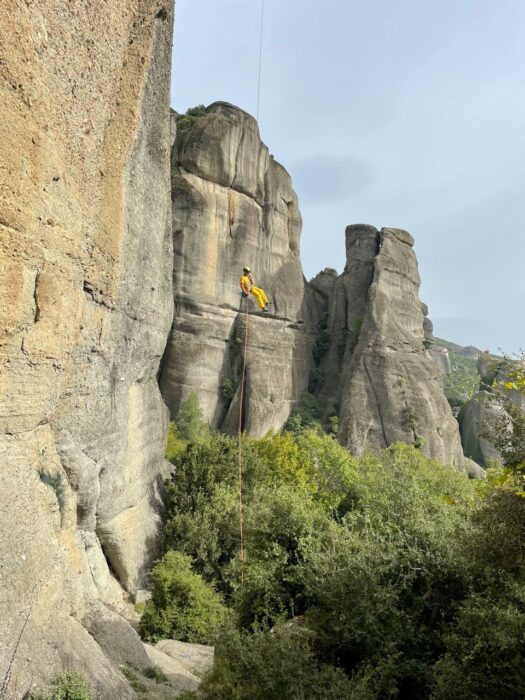

The first climbing records from the Meteora towers trace back to the 10th century, when the first ascetics in the region arrived and settled in the natural hollows of the rocks. The ascetics used scaffolding, nets, and wind ladders for these ascents.

Heinz Lothar Stutte and Dietrich Hasse's 1975 climbs mark the beginning of modern climbing in Meteora.

By 1985, climbers had established more than 200 routes, and the region had grown popular among climbers and adventurers. Amongst the early Greek climbers, Aris Mitronatsios stands out. Throughout the 1990s, the local climbing community made a significant contribution, establishing new routes and accomplishing challenging repeats. They followed the ethics of ground-up bolting, but installed more bolts than usual because of the difficulty of the routes. A typical example was two young climbers from Kastraki -- Christos Batalogiannis and Vangelis Batsios -- who made a decisive contribution to the opening of several now classic routes. Action Direct, Orchidea, and Crazy Dancing stand out among them.

By the end of the decade, the local climbing community had grown significantly, with Nikos Gazos and Nikos Theodorou playing an important role in the development of climbing in the region.

Today, Meteora is a global climbing destination. The Panhellenic Climbing Meeting, for instance, has been held in Meteora since 1988 under the umbrella of the Mountaineering and Climbing Federation, in association with the Kalambaka Municipality and the Kalambaka Climbing Club. This three-day event constitutes a major celebration of climbing each year.

How is it possible?

The giant towers of Meteora are mysterious. One can't help but wonder how people built monasteries on these summits centuries ago, when climbing them can be problematic even for today's sophisticated climbers. How, then, did the monks, shepherds, and hunters climb to these summits?

Based on findings from past ascents, researchers believe they started up the vertical sections by driving wooden or iron stakes into the rock. Then, they balanced a wooden ladder upon the stakes, climbed the ladder, wedged more stakes into the rock, and in the end pulled the ladder up to the new stakes, starting again.

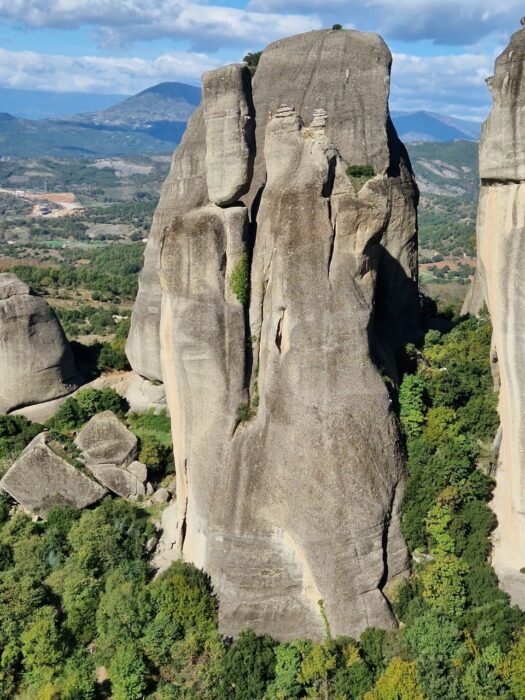

The mystery of the cross

However, one of the biggest riddles in Meteora is the metal cross kept at Varlaam Monastery. In 1348, to celebrate his victory over Epirus and Thessaly, Serbian emperor Stephen Dušan ordered a large metal cross (1.80m x 80cm) to be perched atop Holy Ghost, the most imposing of Meteora's towers. Holy Ghost is a monolithic 300m tower. Climbing to its top involves continuous 5c climbing. Researchers have found no trace of historic attempts on the rock, so we can only assume that somebody climbed 300 vertical metres using just their hands and feet, with no aid whatsoever.

In 1987, a French film crew led by the famous rock climber Patrick Berhault made a film about Meteora climbing. One of the three rock climbers in the cast attempted to repeat a free-solo ascent of Holy Ghost on the route Pillar of Dreams, 250 meters long and 5c+ as an average grade. Eighty metres above ground, he suddenly changed his mind, and the film helicopter had to rescue him. In 1994, American climber Jane Balister took on the challenge and free-soloed it. Not even James Bond -- in 1981, For Your Eyes Only was largely shot in this area -- achieved this goal.

Then, climbing happened, thanks to the Germans

Dietrich Hasse was born in Bad Schandau, Saxony, and from a young age, he was involved in climbing. He quickly became one of Elba's best climbers. He opened many new routes and explored the Dolomites with excellent climbing partners, such as Lothar Brandler (known for the Hasse-Brandler route on the North face of Cima Grande di Lavaredo), Claude Barbier, and Heinz Steinkötter. In August 1975, Hasse and Sepp Eichinger visited Meteora for the first time. They were struck by the imposing towers and established the first four routes in the area.

In the spring of 1976, Hasse and his friend, professional climber and photographer Heinz Lothar Stutte, established even more climbing routes in the area. In 1977, they published the first climbing guide for the region, listing 83 routes.

Interest amongst the German climbing community was growing and seemed to reach a peak with the ascent of the eastern side of Alyssos tower. Hasse, Eichinger, Mägdefrau, and Lothar Stutte opened the Community Path route in a three-day effort, from March 27 to March 30, 1978.

Hasse died in 2022. Two years later, Greek climber Vangelis Galanis made a rope solo first ascent of a new multipitch route on Kapelo Peak and dedicated it to Hasse.

How to get there

From Athens, Meteora is 360km by car (in the direction of Lamia, Domokos, Karditsa, Trikala, and Kalambaka) on a route well serviced by intercity buses and train services. From Thessaloniki, the distance is 230km, by two main routes. The first leads to Kalambaka through Katerini, Larissa, and Trikala. The second goes via Veria, Kozani, Grevena, and Kalambaka. Both routes are possible by intercity bus and train.

You can also reach Meteora from Igoumenitsa, it is a 150km road through Loannina and Panagia. From Volos, it is 140km through Larissa and Trikala. Both routes are served by intercity buses.

Where to stay

The finest place to stay for climbers who want to explore the entire area is Kastraki, which lies between Meteora Towers. Small hotels, rental rooms, and two campsites are available there. Several lodgings are also offered in Kalambaka, a neighbouring town around 2km from Kastraki. I particularly recommend Ziogas Rooms, Thalia Rooms, Hotel Kastraki, and Camping Kastraki.

You can find a supermarket in the town of Kalambaka, and you can purchase basic supplies in a mini-market in Kastraki.

When to find perfect conditions

Climbing conditions are best between April and the middle of June, and from the middle of September to the end of November. The surroundings are lush in spring, but there is a greater chance of rain compared to hot and dry fall. Although summer can be quite warm, some routes are in the shade for a long time during the day. Though winter is more challenging, climbing is still an option on sunny days.

Gear, rules, and final recommendations

In addition to personal climbing gear such as a climbing harness, climbing shoes, a belay/rappel device, carabiners, straps, a lanyard, some nuts, and some friends, it is suggested you take 10-16 quickdraws. Two half-ropes of 60m will help with multipitch climbing, or a 70-80m single rope works for sport climbing.

In April 1976, the Archeological Service and the Orthodox Church granted written permission to climb in Meteora. Climbing is only forbidden on the six towers with inhabited monasteries. Rock climbing is thus permitted without restriction on the remaining 50 solid towers and 80 smaller ones. Campfires, camping, or bivouacking between the towers is strictly prohibited.

On the southern fringe of the High Atlas is one of Morocco's premier climbing destinations, the Todra Gorge. Climbing has been going on here since the late 1960s, and for the first 30 years, it was the main place to climb in Morocco. In the last decade, a revival has taken place, and climbers are flocking there once again.

Yet accurate route information remains notoriously difficult to come by. Parties from all over the world have bolted hundreds of lines over four decades. In many cases, they did not bother recording the details.

Although many routes are well-bolted, other opportunities exist for climbers interested in trad or in setting new routes, especially multi-pitch ones. Both sides of the gorge are suitable, so depending on your needs, you can always find a line that's either in the sun or the shade.

Often, Moroccan souvenir sellers crowd the base of the cliffs, which sometimes turns into a weird adventure. It's not always easy to reach the start of a climb without being convinced to buy something ridiculous.

Climbing beta

Many sport routes in the gorge are over 30m long, so it is worth having a 70m rope. For multi-pitch climbing, we'd suggest a half rope of 60m or even longer if you want to be sure you have enough for every situation.

One advantage of climbing in Todra is the incredible lack of mosquitoes, ticks, spiders, or other intrusive bugs. However, note that there is no mountain rescue service in Morocco, so be even more careful than usual in choosing the right path to the walls.

Crags and sections

As we previously pointed out, the Todra Gorge in Morocco is particularly good for multi-pitch climbing. There are a few single-pitch bolted routes, too. We suggest two crags in particular.

Plage Mansour is located right at the entrance to the gorge and offers almost 30 routes, mostly between 5a and 6b. Many pitches on this crag are over 30m, and a few are even 48-50m. Vertical and slab climbing dominate, and the bolting is good. In the morning, Plage Mansour gets the sun until 2 or 3 pm, when it slips into shadow.

Petite Gorge is the other unmissable crag in Todra Gorge. This section lies about five kilometers from the entrance and can be reached either by car or on foot. Like Plage Mansour, the crag basks in the sun until afternoon.

Multi-pitch routes

Berbertraum is a 340m route leading to the top of Aiguille des Palmeraies. Its 13 pitches range between 4a and 5c, and the longest is 45m. A trail between the rocks leads down from the top, or you can rappel. The route is exposed to the sun until late afternoon, when shadows begin to creep across the upper pitches.

Smoufond is a 6a+ route that leads to the top of Pieds Dans l’Eau after about 150m. To get to the bottom of the wall, you have to cross a river -- a strange obstacle. After the climb, there are two rappels, of 45m and 60m.

Another route that starts by the water is Vole de Defile, which leads to the top of Aguille du Gue. It is four pitches long and graded 6a, V+, V+, and III. There is also another route nearby, called La Diedre, which is partially bolted. Because La Diedre and Vole de Defile are so close to each other, you can connect them and climb to the top with an easier variant, avoiding the Grade 6 pitches on both routes.

How to get there

Marrakech is the nearest international airport, and daily flights are available from throughout Europe. At the airport, you can exchange euros for Moroccan dirhams. It is still largely a cash economy, and you can only use credit cards in places like supermarkets. You can also buy a SIM card at the airport, although you would not use it much in the Todra Gorge, which has no cell coverage.

It takes about seven hours to drive from Marrakesh to the Todra Gorge, so we suggest spending the first and last nights in the city. There is also an airport in Ouarzazate, but flights are available only from April through the summer.

From Ouarzazate to the Todra Gorge takes about two hours by car. Or you can catch a bus from Marrakech to the town of Tinghir. From there, take a taxi 15km to Todra. You don't need a car in the gorge itself, since most areas are just minutes by foot from the entrance.

Accommodation

Tisgui, the closest village to the gorge, has many small hotels and hostels; for example, Etoile des Gorges. Hotel Yasmina is located right in the heart of the climbing, within easy walking distance of most areas. Hotel Mansour and Hotel La Vallee are popular options at the entrance of the gorge. For those seeking a little more luxury, the Kasbah Lamrani in Tinghir is highly recommended.

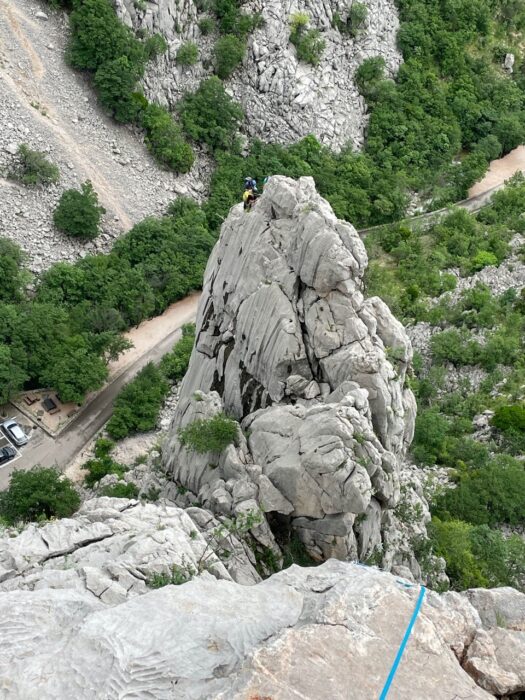

The most famous climbing site in Croatia, the gorges and cliffs of Paklenica National Park offer great climbing variety. It lies outside Starigrad near Zadar, and has routes for everyone from absolute beginners to experts.

A brief history of the National Park

The tombs (tumuli) of Gomila and Paklaric testify that the town dates back to prehistoric times. There was once a Roman settlement here called Argyruntum, and archaeologists found a necropolis from the 1st or 2nd century that contained bronze tools, jewelry, glassware, and ceramics. You can view their finds in the Archaeological Museum in Zadar. The pre-Romanesque church of St. Peter dates back to the 10th century.

Paklenica became a National Park in 1949. In 1978, UNESCO proclaimed the entire Velebit region a biogenetic reserve.

Inside the park, each of the two main gorges has a name that underlines the difference between them: Velika (Great) Paklenica and Mala (Small) Paklenica.

Velika Paklenica

Velika Paklenica consists of two valleys. The longitudinal valley runs parallel to the Southern Velebit range, while the other is carved between the peaks of Debeli Kuk and Anica Kuk. Anica Kuk is the only place in the park where climbing is allowed.

Because of its relative inaccessibility, the upper part of Velika Paklenica has developed a lush forest. In the transverse valleys, influenced by the Adriatic Sea, shrubs and Mediterranean maquis cover the slopes.

The climatic and topographical differences that characterize this region, which extends from the peaks of Velebit (1,700m) to the sea, are the reason the flora and fauna are so interesting. Botanists have recorded over 500 plant species. The fauna is also rich: over 500 species of insects, several reptile species, and as many as 200 different types of birds.

A climbing Mecca

In Paklenica, the rock is mostly karst limestone. It is very compact, although sharp in places. There are numerous routes of all difficulty levels and lengths, from single pitches on cliffs to multi-pitch routes to a height of 350m.

The style also varies, from technical slabs to large overhangs. The large walls host numerous well-bolted routes that climb on ridges or easy slabs. But there is no shortage of long sport routes that tackle much more sustained terrain with difficulties up to 8a. In addition, there are a handful of beautiful trad routes, protected only with nuts and Friends. For those who want to try something different, there are some interesting artificial routes.

When it all began

The first climbers visited Paklenica in the late 1930s, but the first route was Brahm in 1940. Between 1957 and 1969, Croatian climbers largely had the gorge to themselves and opened many new routes. Today, many of these are considered true classics, such as Mosoraški (1957), Velebitaški (1961), and Klin (1966).

Later, it was mainly Slovenian climbers who opened further new routes. Among them was the legendary Franc Knez, who opened around 40 routes. Many of Knez's routes remain among the most difficult in Paklenica today.

During the 1980s, Italian Mauro Corona established the first short sport routes in Klanci, the narrowest part of the canyon. His first route was Stimula, 7a. Soon after, Maurizio Zanolla made the first free ascent of what is still the hardest route in Paklenica: Il Marattoneta (8b+). Adam Ondra onsighted it in 2020 and also made a new variant, named Genius Loci (9a).

And how it developed

During the breakup of Yugoslavia in the 1990s, the park was closed for a few years. When it reopened in 1995, Austrians Ingo Schalk and Gerhard Grabner immediately opened a great new route, Waterworld (7b+).

Currently, the most active climbers are Croatians Boris Cujic and Ivica Matkovic, who are responsible for a whole series of new routes. They have also fixed and rebolted numerous old routes, replacing countless rusty bolts.

While there is little chance of discovering something new on the big walls of the gorge, there is still potential for hard sport routes in sectors like Rupe, or even in more distant crags, just outside the Paklenica canyon.

Respecting the rules

Paklenica is a national park, so there are strict regulations for environmental protection. There are also areas where authorities prohibit climbing, such as Mala Paklenica, and on Debeli Kuk in the Velika Paklenica gorge from the lower to the upper parking lot. Climbing is also prohibited from Manita Pec to the upper part of Velika Parklenica. These prohibitions protect bird habitat and help to avoid accidents from rockfall.

There is a fee to enter the park, but there are three and five-day ticket options for climbers that are valid for 30 days. Climbing officials supervise the climbing in Paklenica. They ensure the safety of the routes and are in charge of maintenance. Equipping new routes and installing new equipment on old routes requires permission from the Paklenica National Park management.

The best time of the year

The best time of year is from April to the end of October. In winter, strong winds are a problem. However, the Crljenica section has recently been developed, and with its sunny position, it is suitable for climbing even in winter. During the spring, expect frequent showers, though the karst dries quickly. In summer, it can be hot, but you can always find a place in the shade, such as on Anica Kuk, throughout the morning.

Where to sleep, where to eat, where to meet

In Stari Grad, there are several shops, open even on holidays, a gas station, and everything you need for a pleasant stay. If you want to camp, many campsites offer budget accommodation, such as NP Paklenica, Marko, Vesna, Peko, and Popo.

Affordable rooms are available at Ana Marasovic, Pansion Andelko, Hotel Rajna, and Restaurant Paklenica.

Other activities and interesting sites

Although climbing is prohibited, we highly recommend a trip to the nearby Mala Paklenica gorge. This valley is smaller and rarely visited, so the nature tends to be more primeval and wild. In Velika Paklenica, visiting the Manita Pec cave is another must.

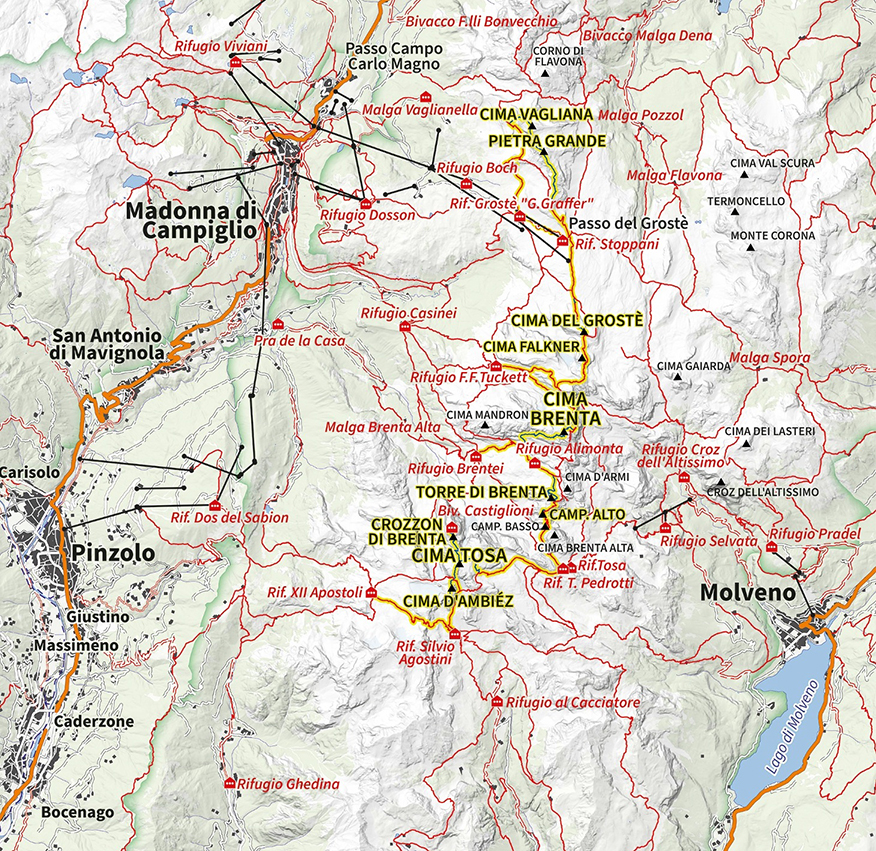

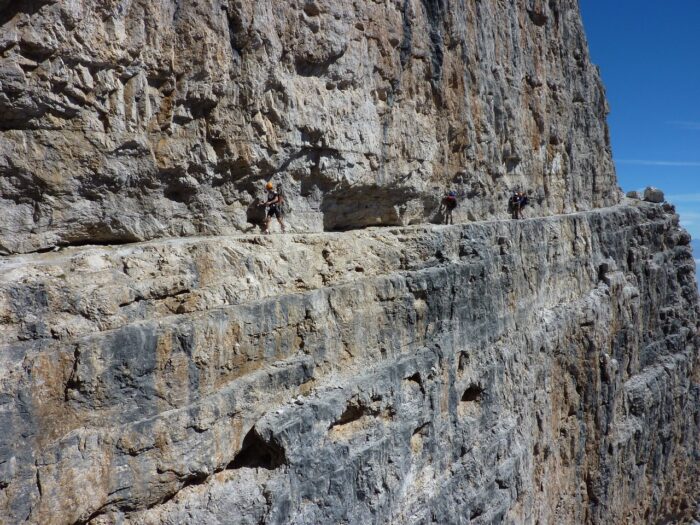

Rivers and a highway separate the isolated Brenta Dolomites from the rest of the range. The main peak, the Campanil Basso, is so iconic that, according to tradition, no man from the local Italian town of Trentino can be considered a climber until he has scaled it. However, the Brenta is hard to access from the surrounding valleys, and the rugged and complex massif is ill-suited to high-altitude traverses.

Despite this, in the early 1930s, a couple of men had a vision: to connect the narrow forks that run through the central part of the Brenta. They hoped to exploit an incredible system of natural ledges that roughly follows the watershed ridge that divides the eastern side (which slopes down towards the village of Molveno) from the western side (which looks out onto Madonna di Campiglio and Rendena Valleys).

These natural balconies and ledges are a true geological miracle. In 1937, they finally led to the via ferrata Via delle Bocchette. (A via ferrata is a series of ladders, cables, and other fixed aids that make what would otherwise be a serious climb over a cliff face into merely an airy hike.) The route was never designed to touch the peaks, which remained the exclusive domain of mountaineers.

From Via delle Bocchette to Via delle Normali

Almost a century later, taking inspiration from Via delle Bocchette, Trentino's mountain guides tried to revive some of the region's pioneering "normal" routes that are now out of fashion.

In 2020, Via delle Normali -- which means "the way of the normal routes" -- was finally defined, also thanks to the effort of Gianni Canale, the president of the local mountain guides association. The result is a mixed climbing and trekking route, 45km long, over the wildest and most isolated part of the Dolomites. It passes through six stages from the south to the north of Brenta, involving its 10 main peaks, all higher than 2,900m but with a difficulty never greater than Grade 3 on the UIAA scale. Unfortunately for Trentino's wannabe climbers, Campanil Basso is not included.

Here's a detailed description of each stage, although we highly recommend contacting local mountain guides before taking on this incredible route. You stay overnight in rifugios -- well-equipped mountain huts.

Stage 1: Rifugio XII Apostoli - Cima d'Ambiez - Rifugio Agostini

The first stage of Via delle Normali crosses Cima d’Ambiez (3,102m), with a climb along the southern ridge and a descent on the northern side.

The ideal base for starting your adventure is Rifugio Agostini in Val d’Ambiez. But those setting out to complete the entire six-day crossing could consider starting from Val Brenta and climbing up to Rifugio XII Apostoli for the first evening’s overnight stay. This allows you to easily return to your car at the end of the sixth stage.

In this case, in the morning, you will need to calculate two to three hours more to reach Rifugio Agostini via Bocchetta dei Due Denti and via ferrata Castiglioni. From Rifugio Agostini, you then need three to four hours to climb the normal route on the south wall, along a beautiful ridge offering wide views as far as Lake Garda.

From the summit, the cairns indicate the descent, which takes place on the north side with nine rappels to Bocca d’Ambiez. Then, via ferrata Ideale descends to the Ambiez glacier (crampons are recommended) and to the path that leads back to Rifugio Agostini. The descent takes another three to four hours. Equipment required for this first stage is a descender, a 60m single rope, and four quickdraws.

Stage 2: Rifugio Agostini - Cima Tosa - Crozzon di Brenta - Rifugio Pedrotti

The second stage of Via delle Normali includes the ascent to Cima Tosa (3,136m) along the Migotti route. There is an optional crossing to the summit of Crozzon di Brenta (3,135m), returning along the same ridge, and then descending along the normal route on the southeast side.

From Rifugio Agostini, you need to go up the Ambiez Glacier (crampons are useful) and the via ferrata Ideale to Bocca d'Ambiez. Then take the Migotti route to the summit (four hours from the rifugio). Those who decide to venture along the ridge that leads to Crozzon di Brenta should not be fooled by the shortness of the route as the crow flies; it is longer and more laborious than it seems. Calculate at least four more hours for the outward and return journey.

The descent from Cima Tosa involves three rappels and about two hours to the Rifugio Tosa-Pedrotti. You need a descender, a 60m rope, and five quickdraws.

WARNING: Rifugio Tosa-Pedrotti will undergo renovation work during the summer; check that you can stay by calling the phone number on the website.

Stage 3: Rifugio Pedrotti - Campanile Alto - Torre di Brenta - Rifugio Alimonta

The third stage of Via delle Normali is one of the most spectacular and involves climbing Campanile Alto (2,937m) and/or Torre di Brenta (3,014m). The stage starts from Rifugio Tosa-Pedrotti and follows via ferrata Bocchette Centrali to below the northeast face of Campanile Alto in about an hour. Then you climb along Via del Caminone, which you also follow for the descent, involving eight rappels. In total, it is about three to four hours round trip.

To climb Torre di Brenta, continue on via ferrata Bocchette Centrali to the wide snowy channel under Bocchetta degli Sfulmini. Then climb a curving path, first on the south-east side, then on the north side, using a wide ledge. The upper section of the descent follows the ascent route, but once you reach the ledge, you continue to descend on the north side until you reach the ice of Vedretta degli Sfulmini (crampons essential), heading toward Rifugio Alimonta.

If done entirely with double rope, the descent involves 21 rappels, so plan about seven hours for the ascent and descent of Torre di Brenta. You need a descender, a 60m single rope, and five quickdraws.

Stage 4: Rifugio Alimonta - Cima Brenta - Rifugio Tuckett

The fourth stage of Via delle Normali climbs the queen of the massif, the severe, imposing Cima Brenta. It is the highest peak of the Brenta Dolomites, though Cima Tosa (climbed during Stage 2) is currently marked on IGM maps as the highest (3,161m). But a team using electronic instruments determined its new height in 2015. The change could be due to the partial melting of the ice cap that covers it. Thus, 3,151m Cima Brenta became the highest peak.

The stage starts from Rifugio Alimonta, heads to Rifugio Brentei, and climbs the southern side of Cima Brenta along the route of the 1882 first ascent. It should take around four hours.

To descend from the summit, follow the ridge toward the north, lowering yourself with a couple of rappels to the notch that overlooks the northern slide. Then climb a tower on the opposite side and continue the descent with another four rappels until you reach the Garbari ledge in about an hour and a half.

Next, take the via ferrata Bocchette Alte, which leads to Rifugio Tuckett in two more hours. You need a descender, a 60m single rope, and four quickdraws.

Stage 5: Rifugio Tuckett - Cima Falkner - Cima Grostè - Rifugio Graffer

On the fifth day, there are fewer technical difficulties, but the environment remains superb. You can spot peaks Cima Falkner (2,999m) and Cima Grostè (2,901m), which are accessible via deviations from the route.

You start from Rifugio Tuckett and go up toward Bocca di Tuckett. Or, you can cut along the via ferrata Dallagiacoma variant. Once you have taken the via ferrata Benini, after a short while, you find the deviation for the ascent to Cima Falkner. The ascent and descent follow the same track, which takes about an hour. After descending and while continuing to Bocca dei Camosci, you then find the deviation to climb Cima Grostè from the southeast side. It is an easy 50m climb from the shoulder to the summit.

The descent is on the northeast side, with a couple of optional rappels. The entire stage, linking both peaks, takes around nine to ten hours, from Rifugio Tuckett to Rifugio Graffer. As with the previous stages, you need a descender, a 60m single rope, and, in this case, three quickdraws.

Stage 6: Rifugio Graffer - Cima Pietra Grande - Cima Vagliana - Rifugio Graffer

The sixth and final stage of Via delle Normali closes the crossing beautifully, with a long and airy ridge that allows you to touch Cima Pietra Grande (2,936m) and Cima Vagliana (2,864m).

From Rifugio Graffer, you need to go to Passo Grostè and take via ferrata Vidi for a while. Then continue along the southern ridge, called Cresta dell’Oreste. Compared to the previous stages, this is lower quality rock and requires extra attention to avoid falling rocks. But the route is logical, with a view that extends over a good part of the northern Brenta.

There are five rappels along the ridge. From Cima Vagliana, go down to the northwest and descend the scree until you intercept via ferrata Costanzi. This section passes through Orti della Regina -- a spectacular hike on scree and easy rocks at the foot of Cima Pietra Grande -- and leads back to Rifugio Graffer. The stage requires eight to nine hours. You need a descender, a 60m single rope, and five quickdraws.

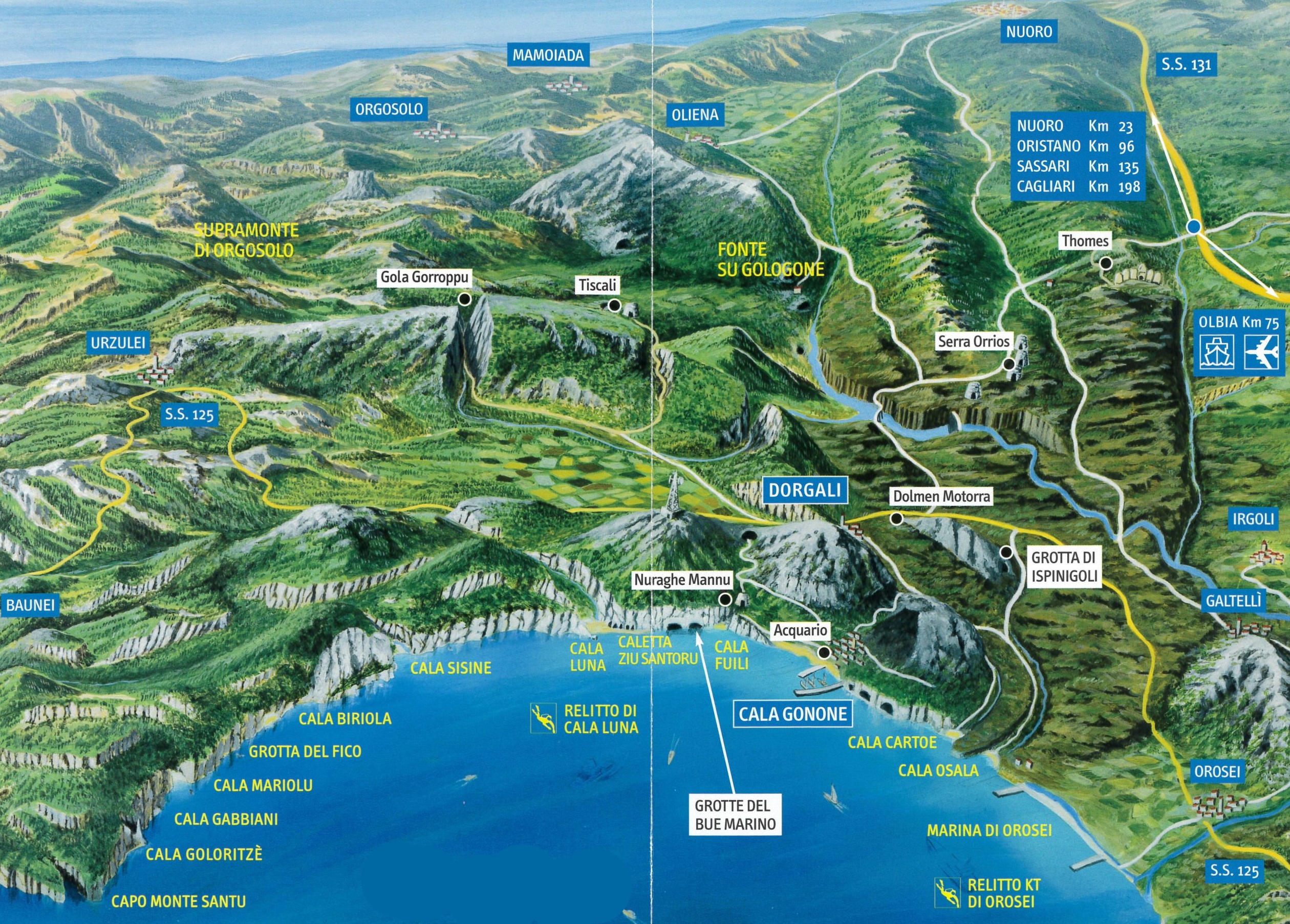

The second-largest island in the Mediterranean, Sardinia's charm lies in its wild landscapes, its heavenly beaches, and the mistral wind that blows away the summer heat, giving relief to hikers and climbers.

One of Sardinia's best areas for hiking and climbing is the Gulf of Orosei, which stretches 30km along the eastern coast, bordered by the foothills of the Supramonte massif. A week to 10 days is enough to see the highlights. It is certainly enough to contract "Sardinian disease," a terrible feeling of nostalgia that will make you want to return as soon as possible.

Here are 10 activities and places to try.

1. Cala Goloritzé, the best beach in the world (plus an iconic climb)

A few weeks ago, The World's 50 Best Beaches of 2025 awarded first place to Cala Goloritzé, for "its wild beauty that has the power to captivate at first sight."

In the 1980s, two well-known Italian climbers -- Maurizio Zanolla and Alessandro Gogna -- had already discovered its potential. But they didn't focus on the beach but rather on the extraordinary climbing potential of the Aguglia, a massive free-standing needle that towers above Cala Goloritzé. The limestone walls appeared to offer slab climbing in amazing surroundings.

Manolo and Gogna first summited the feature in December 1981, along a route they called Sinfonia dei mulini a vento ("Symphony of the windmills"). Today, Aguglia has many routes. One of the most popular is Sole incantatore, opened by Maurizio Oviglia in 1995. Aguglia's summit is a once-in-a-lifetime experience for many climbers.

To reach Aguglia (and the beach), drive to Baunei and then follow the signs for Ristorante del Golgo. After a 10km drive to Ristorante del Golgo, turn right to Cala Goloritzé's official parking area, near Bar Su Porteddu. From there, it is an easy one-hour hike on an obvious uphill path. At the end, it slopes gently downhill to the beach and Aguglia.

2. Cala Luna, Lina Wertmüller's bay

Hiking and swimming are a perfect combination in the Gulf of Orosei. Take Cala Luna, for example. Located halfway between the towns of Baunei and Dorgali, it was the set for Lina Wertmüller's 1974 masterpiece, known as Swept Away in English. If you, too, want to be "overwhelmed by an unusual fate in the blue sea of August" -- that is what the title means -- Cala Luna's outstandingly blue sea is the ideal place.

The bay owes its name ("luna" means moon) to an 800m sandbar that looks like a white crescent moon, with six enormous caves that open onto the beach. You reach the beach after a six-kilometer hike, immersed in the trees and overlooking the coast.

The hike to Cala Luna begins at another nice beach, Cala Fuili, and the last cove reachable by car or bike from the nearby village of Cala Gonone. Start early to enjoy the sunrise and a first swim in Cala Fuili. Then hike to Cala Luna before midday to avoid the hottest hours and the crowds.

3. Selvaggio Blu, the most challenging trail in Italy

Conceived in 1987 by photographer and alpinist Mario Verin with the help of Peppino Cicalo, president of the local branch of the Italian Alpine Club, Selvaggio Blu extends for over 40km from Santa Maria Navarrese to the beach of Cala Sisine. On average, the trail takes four days to complete.

The trail's creators wanted to raise awareness of Sardinia in the outdoor community. They created it by restoring old mule tracks, marking the route, and training local mountain guides. A guide is actually recommended, both for route finding and for help with the more exposed sections, rated up to grade IV on the UIAA Scale. After each stage, you sleep outside, in caves or tents.

The best time for Selvaggio Blu is in late spring or early fall. Many local guides organize trips, but not all guides are UIAGM certified. Contacting the local guide office in Cala Gonone, run by the UIAGM guide Stefano Michelazzi.

4. Gorropu Canyon

In May 1999, Rolando Larcher and Roberto Vigiani set up a multipitch climbing route, following strict ground-up ethics, in Sardinia's most spectacular canyon: Gorropu. Hotel Supramonte is now one of the world's best-known climbing routes, with a name that comes from a song by Fabrizio De Andre, one of Italy's most famous songwriters. A 400m line, up to an 8b lead to the top, it has attracted many famous climbers: Stefan Glowacz, Beat Kammerlander, Steve McClure, Cedric Lachat, Nina Caprez, and Adam Ondra (onsight, in 2008). But if you're not as good at climbing as they are, there are plenty of hiking routes to explore.

Hikers pass gorgeous views of barren cliffs, Mediterranean vegetation, and a juniper forest. The starting point is usually Passo di Ghenna Silana, 30 minutes by car from Dorgali and Cala Gonone. From there, you can choose between various paths.

5. Monte Oddeu, a multi-pitch playground

If you want to try more multi-pitch climbs near Gorropu Canyon -- but need something easier than Hotel Supramonte -- Monte Oddeu is the best and most accessible area. Located above the Flumineddu River between the canyon and the ancient village of Tiscali, it is only 12km from Dorgali. The routes are 200m high on average, with a grade range from 6a to 7a.

From Dorgali, follow the signs to Gorropu and Tiscali, driving on a wiggly road toward the valley below. There are parking spots by the bridge that crosses the Flumineddu River. Walk over the bridge and turn right towards Tiscali, following a narrow footpath on the left which enters the woods. Keep left, walking by a wire fence to the base of the wall. Most of the routes are sport climbing, with some mixed and a few trad.

6. What about the crags?

Sardinia and Cala Gonone were famous for their crags years before Greece and Kalymnos. Rediscovering them while most European climbers are focused on the Greek island is a good idea. We suggest five crags in particular.

Bidiriscottai

Biddiriscottai is one of the most fascinating sea-facing crags in Sardinia. Only 20 minutes by foot from Cala Gonone, it features 60 climbing routes, spread over 250m of solid limestone. They range from easy and short to extreme overhangs.

In 2021, a massive redevelopment and safety campaign equipped most of the routes with titanium bolts.

Cala Fuili

We already mentioned Cala Fuili as a starting point for the hike to Cala Luna. If you are looking for a unique climbing crag in Sardinia, Cala Fuili is a go-to spot. The easiest walls directly face the sea, but others are located in the nearby canyon. Puschtra is the hardest section, with long and overhanging routes. The average grade is 7a, and the rock is spectacular, although it may be humid and slippery, especially when the sirocco wind blows, carrying salted sea air.

Buchi Arta

The vertical wall of Buchi Arta is not huge but has over 50 climbing lines. Natural cuts in the rock and holds that seem precisely shaped for your fingertips welcome climbers of all ages and skill levels.

Most routes are between 25 and 30m, guaranteeing a nice, long vertical journey. The base of the crag is wide and shaded until early afternoon, perfect for climbing in the morning and swimming after.

La Poltrona

La Poltrona is one of the oldest climbing areas near Cala Gonone. The central wall is an enormous leaning slab with about a dozen multi-pitch routes. On the lower right wall, there are many easy single routes characterized by old-style slabs that demand certain balance and precise foot positioning.

La Poltrona is thus a great "school" to learn the basics of outdoor rock climbing, especially for those who come from the gym and are looking for a safe place to practice basic outdoor skills while on holiday. Easy to reach, at the end of the main road that leads from Dorgali to Cala Gonone, there is a roundabout with the restaurant "La Poltrona" on the left-hand side. The crag is five minutes from the restaurant.

S'Atta Ruja

S'Atta Ruja is the nearest crag to Dorgali. Park the car in the town center and walk five minutes to the crag. Facing west, it is a valid alternative to sunbathing on the beach, at least during the hottest summer mornings. The routes are 25m long, with grades from 5c to 8a.

7. And in case of bad weather?

Not everyone is lucky with holiday weather. In case of bad weather, you can choose between two interesting options in the area. The Ispinigoli karst cave, a 15-minute drive from Dorgali, has been open to the public since 1974. This natural wonder contains a 38m limestone column that joins the vault to the base of the cave. Researchers found traces of human bones and jewelry dating back to the Bronze Age inside the cave, suggesting it was a burial place.

Another rainy day alternative is a brief visit to the village of Orgosolo, a 40-minute drive from Dorgali. It is the land of the Canto a Tenore, a polyphonic folk song that is part of the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage. Little lanes and stone houses are enriched by beautiful paintings, which have made the village internationally famous. Many artists have contributed to the creation of an outdoor museum. Hundreds of murals color the streets and tell the story of traditions, culture, and dissent.

8. Lodging

Cala Gonone is the most central town to explore the Gulf, but people tend to ignore nearby Dorgali's potential. It is not by the sea, but it is just a 15-minute drive from Cala Gonone. There are plenty of hotels, as well as rooms and apartments available for rent.

We suggest the farmhouse Conca 'e Janas in Dorgali, where you can rent rooms at affordable prices. There's also the Nuraghe Mannu, which is on the main road that leads to Cala Gonone from Dorgali and has a camping site for tents and vans. In both places, the food is extraordinarily good.

9. How to get there

The most practical and cheapest way to get to the Gulf of Orosei is by car. Italians take their car on the ferry to Olbia from Genoa or Livorno. If you fly in, you can rent a car after landing at Olbia's airport. The road that leads from Olbia to Dorgali takes about an hour and a half.

10. Other interesting things

Before leaving Sardinia, you should grab two things to take home: cheese and leather. Dorgali has both. Pelletteria Fara is a historical boutique that sells leather items at affordable prices. These are traditional products; for example, you can carry home a "taschedda," a brown leather backpack that was used by shepherds.

Cooperativa Dorgali Pastori is ideal for those who want to discover Sardinian dairy tradition.