A 63-year-old speleologist has been rescued from the Abisso Paperino cave system in northern Italy after suffering a head injury approximately 40m below the surface. The incident occurred on Sunday when falling rocks struck the man while he was in the cave with team members.

Specialist emergency responders, including a medical team, reached the injured caver the same day. He received treatment inside a specially installed heated tent within the cave. While the severity of the head injury remains unclear, the man was unable to exit the cave system without assistance.

Inside Italy’s Abisso Paperino cave system

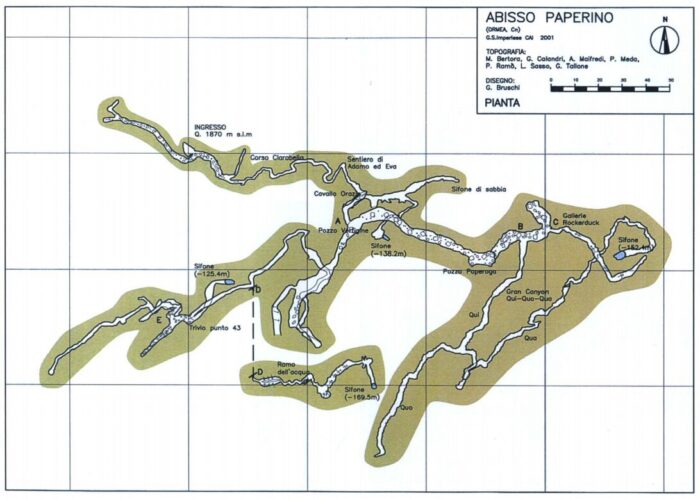

The Abisso Paperino cave system in northern Italy reaches depths of up to 154m and is approximately 1,700m long. Accessible via a dirt road, the cave begins with a 28m vertical shaft that opens into a complex labyrinth of underground galleries, shafts, and winding sections. Notable features within the system include the Cavallo Orazio chamber, the central Pozzo Vertigine shaft, and a series of fossil galleries and water-filled siphons, making it an interesting site for speleologists and cavers.

To extract the injured man from the Abisso Paperino cave system, rescue teams used controlled explosive charges to widen three critical passages. This allowed members of the Italian National Alpine and Speleological Rescue Corps to safely transport the man back to the surface through the narrow, challenging terrain.

The injured speleologist’s ascent to the surface on Monday involved climbing through two vertical shafts, each approximately 15m high. Rescuers also had to navigate a complex maze of tight, winding cave passages to complete the operation successfully.

On the border between Chile and Argentina, on the edges of a turquoise lake in the heart of Patagonia, one of the world's most visually spectacular cave systems awaits.

Known variously as Capillas de Mármol, The Marble Chapel, or the Marble Caves, the caverns comprise smooth, striated marble that sit just above the waterline of the glacier-fed lake. When you combine the glossy surface of the marble with the light reflecting off the glacier silt in the water, you get a colorful show that, at first glance, seems more at home in a sci-fi movie than on good old planet Earth. Throw in vaults, columns, and chambers carved out by erosion, and you have a natural wonder for the ages.

“They were formed at temperatures of around 300˚C to 400˚C, between 10 and 15km underground,” geologist Francisco Herve told the BBC.

The caverns started out as limestone before the planet's intense heat and pressure transformed them into marble. The cake-like layers are the result of varying mineral compositions, with the whitest parts mostly made out of calcium carbonate.

Fast-acting erosion

"These calcareous rocks...are among the most soluble that exist,” Herve explained.

That means the erosion that formed the caves themselves probably happened quickly, shortly after the glaciers that carved Patagonia's iconic landscape began to recede. That was probably about 10,000 to 15,000 years ago, the geologist said. And by "quickly," we mean that relatively. Scientists estimate the process took about 6,000 years.

As for why glacial silt produces such a shocking blue-green color? An accident of physics. The pulverized dust that used to be mountains happens to absorb short-wavelength light (purples and indigos) while reflecting blues and greens.

The Marble Caves are part of a larger cave group that dots the shores of Lago General Carrera. No one knows who "discovered" the caves — people have likely known about them since they developed. Humans have continuously inhabited that portion of Chile for over 12,000 years, meaning they would have gotten to watch the caves develop over hundreds of generations.

The whole area was designated a natural sanctuary in 1994 to help preserve it for future generations. But that doesn't mean you can't visit it.

Tourism over ranching

Three decades ago, everyone in the area was involved in the cattle industry. Now a good chunk of the local population works in tourism. The Capillas de Mármol is only accessible by boat, and locals from the nearby hamlet of Puerto Río Tranquilo are on hand to facilitate trips. According to several travel websites, spring and fall are the best times to catch the caves at the perfect synthesis of water level and reflected light.

An injured cave explorer was successfully pulled into daylight early Wednesday morning after a four-day rescue, multiple media outlets are reporting.

Speleologist Ottavia Piana was exploring an uncharted part of the Bueno Fonteno cave near Bergamo, Italy when a rock gave way under her feet. The 32-year-old caver fell five meters and sustained fractures to her face, knees, and ribs. She was with eight other people when the accident occurred. Rescuers were alerted to the incident on Saturday.

The charted portions of the cave network extend over 19km, and the uncharted parts are narrow, twisty, and difficult to navigate. It was a four-kilometer journey through previously unexplored terrain from the site of Piana's accident to the surface.

View this post on Instagram

Never again

“The morphology of the cave also made it difficult, with some areas at risk of a landslide, which is also why the accident occurred, as a rock gave way beneath her feet," Mauro Guiducci, vice-president of the Italian National Alpine and Speleological Rescue Corps (CNSAS) said in a press conference.

Responders strapped Piana to a stretcher and slowly moved her through the web of tunnels, pausing every 90 minutes to asses her condition. The group of 159 expert volunteers occasionally used small explosive charges to clear blocked passages. The rescuers also laid telephone cables across the entire route to facilitate communication.

Rescuers accelerated their efforts on Tuesday after becoming more concerned about Piana's condition. In the end, they stepped into fresh air 12 hours earlier than expected.

“She’s speaking very little but said she would never enter a cave again,” one rescue medic told the Italian press.

Piana has many years of caving experience, but this is the second time she's been rescued from the Bueno Fonteno system. Seventeen months ago, she was trapped for two days after breaking a leg.

View this post on Instagram

Federico Catania, another CNSAS member, told the Italian press that Piana was well-prepared for the exploration. “We don’t judge the people we help,” he said. “We just know that there is a person in difficulty, and we intervene. We can perhaps judge some inexperienced behavior, but this was not the case.”

The Chihuahuan Desert is a sparse but stunning ecosystem straddling the border between Northern Mexico, Southern New Mexico, and West Texas. High in elevation and low in humidity, the desert plays home to spiky ocotillo plants, blinding dust storms, and fragrant green chili farms.

In the cool evenings, coyotes, antelope, and ringtails play out the timeless drama of desert survival. Kangaroo rats scamper beneath the creosote bushes, licking dew off the leaves and hoping not to be ambushed by rattlesnakes. The sunsets are spectacular.

But the wonders of the landscape don't stop at the surface. Far underground, another awe-inspiring treasure awaits.

A quarter-of-a-century ago, two brothers drilling a ventilation shaft for the Naica Mine in Chihuahua, Mexico, stumbled across something fantastic. The miners were working 300m underground when they broke into a basketball-court-sized cavern filled to the brim with the largest crystal formations they'd ever seen.

What their lights illuminated would come to be called "The Cave of Crystals," and it's as deadly as it is beautiful.

11m crystals galore

As the brothers shone the first light into the cavern, they saw a tangled maze of huge selenite crystals that almost defy words. The largest is 11m long with an estimated weight of five tons, but all of them are huge. The crystals are a milky, translucent white. Their sheer scope and maze-like formation — combined with manmade light — create an otherworldly effect that tends to leave observers temporarily speechless.

"There is no other place on the planet where the mineral world reveals itself in such beauty," Juan Manuel García-Ruiz, a geologist at the University of Granada, told National Geographic in 2007.

García-Ruiz was part of a team intent on discovering how the natural wonder formed. To do so, he studied tiny pockets of water trapped inside the crystals. What he and others uncovered involves magma, as so many of the planet's best spots do.

Roughly 4km below the Cave of Crystals is a large pool of magma that radiates a constant heat. At some point in the distant past, the cave was flooded with water rich in a mineral called anhydrite. For a million years, the magma kept the water at a constant temperature of 58°C, allowing the anhydrite to dissolve into gypsum. Gypsum likes turning into selenite crystals, and so, firmly in their sweet spot, they did just that.

Eventually, the water drained out of the cavern (thanks to water pumps elsewhere in the mine), leaving behind a maze of crystals.

Beautiful death

The Cave of Crystals comprises at least four chambers: the Cave of Crystals, the Queen's Eye Cave, the Candles Cave, and the Ice Palace. The qualifier "at least" is there because 25 years after its discovery, the cavern system has yet to be fully explored.

That's because while the caves are friendly to crystal formation, they aren't necessarily friendly to human survival.

Temperatures inside the caverns can get up to 58°C, near record-setting temperatures in Death Valley. But as the old saw goes, it's not the heat that gets you, it's the humidity. In the Cave of Crystals, humidity can reach a whopping 90 to 100 percent.

Those conditions will kill you, and it doesn't take long.

So, when the first scientific explorations commenced, they required a little engineering first. A team led by cave mineral specialist Paolo Forti, of the University of Bologna, developed special refrigerated cave exploration suits before venturing forth.

The team started with standard cave exploration overalls, then added a thick tubing layer connected to a backpack. The backpack held 20kg of water and ice, which was then pumped through the tubing. Add a refrigerated respiration system, and you're all set to explore the Cave of Crystals. For a few minutes.

The system, though sophisticated, only keeps you cool for about thirty minutes at a time.

Another hurdle the team had to jump was the crystals themselves. Take a glance at photos from the Cave of Crystals and you'll see just how physically demanding it must be to navigate them. Exploration indicates more chambers, but that would mean destroying some of the crystals blocking the (prospective) openings, something no one involved is willing to do.

A window closes — for the best?

Operations ceased in the Naica Mine in 2015. With the pumps turned off, the caves reflooded, halting further scientific exploration.

But the discoveries made in the brief 15-year window were significant. Ancient pollen experts, geochemists, geologists, and hydrogeologists all had a chance to study the stupendous formations.

Interestingly enough, biologists also had a field day. They hoped that as the crystals formed, they trapped DNA from ancient bacteria swimming around in that million-year-old hot water. At first, they came up dry, but in 2017, speleologist and extremophile expert Penelope Boston from the New Mexico Institute of Mining and Technology announced a discovery. She had discovered ancient bacteria embedded in a few of the crystal samples taken before the caves reflooded.

The bacteria are unique and don't resemble anything currently known to science.

For now, the caves will remain closed to human exploration, though that might change if operations in the mine resume. In the meantime, while those of a scientific bent might mourn the loss of the knowledge hidden in the crystals, we can at least take solace that the Cave of Crystals has returned to the same state we found it in — a rare thing to be able to say.

The Saint-Marcel cave is one of France's largest and best-researched cave systems. Its caverns and tunnels stretch underground for 64 kilometers. Humans have sheltered there since the Middle Palaeolithic era. Now, a new study proves that these ancient humans went far beyond the cave entrance. Somehow, they found a way to navigate this labyrinth.

Scientists discovered a series of broken speleothems -- mineral deposits, like stalagmites -- over a kilometer and a half inside the cave's twisting pathways. At first glance, this does not suggest anything exciting. When many caves were first explored in the late 19th century, people often snapped off bits of the deposits as souvenirs. But some breakages deep within date back 8,000 years.

A broken stalagmite can regrow, as long as it has a steady supply of water. The water deposits minerals on the rock, which accretes or gets bigger. Lead author Jean-Jacques Delannoy and his team noticed that the broken stalagmite pieces had been arranged to create a structure in the cave.

The researchers dated the rocks with uranium-thorium dating. As uranium decays, it produces thorium, which is insoluble in water. By working out the ratio of uranium to thorium in the mineral deposits, they could figure out when those ancient cave dwellers had broken the stalagmites.

The speleothems themselves are between 125,000 and 70,000 years old. The breakages occurred 10,000 and 3,000 years ago -- not during those 19th-century souvenir hunts. Finally, the structure in the cave dates to 8,000 years ago.

"The evidence for prehistoric human activity in the cave of Saint-Marcel is conclusive,” they state in the new study.

Speaking to the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Delannoy said, "This raises the question of cave knowledge at that prehistoric period, their ability to explore and cross shafts, and their mastery of lighting.”

The Saint-Marcel cave system is not easy to navigate. Nowadays, artificial lighting and walkways guide tourists easily through such caves. But without this, they are in complete darkness, and hazardous pits lie along the pathways. Even modern cave explorers find such a route challenging. So how did ill-equipped prehistoric people manage it 8,000 years ago?

The researchers are now trying to find that out. It is possible that they used oil lamps or torches. Soot deposits in the caves may reveal that. However, Delannoy accepts that many of the cave's secrets will likely remain a mystery -- why they went in so deeply, what drove them to create that structure inside it. "We no longer have access to their thoughts,” he admitted.

Five days ago, there was a difficult, 15-hour rescue of three people on 3,800m Grossglockner in the Austrian Alps.

On Jan. 5, according to Alpin.de, two 40-year-old brothers and their 57-year-old guide arrived at Grossglockner after a long drive from the Czech Republic. Despite snow, low temperatures, strong wind, and a bad weather forecast, they decided to climb the south side of the peak. They began around 6 am, carrying ski touring and climbing equipment.

At 3,500m, the three men could not go any higher, nor could they descend in the bad weather. Around 11 pm that evening, they phoned for rescue. The helicopter couldn’t fly, so 13 rescuers and a local police mountain guide climbed through the night toward the stranded mountaineers.

The next morning, at about 5 am, the rescuers reached a mountain hut. From here, they set off toward the south face of Grossglocckner and eventually reached the trio.

The complicated rescue cost around 20,000 euros, and the public prosecutor’s office is investigating whether the three men will have to pay the cost.

Tourists stuck in flooded Slovenian cave

In southwestern Slovenia, there was another rescue earlier this week, this time in the famous Krizna Jama cave. Five tourists became trapped after sudden flooding, according to Sloveniatimes.com.

On Jan. 6, a Slovenian family of three with two guides entered the cave on a tour. Then water levels suddenly rose because of strong rains in the area, trapping the group. When they didn't reappear several hours later, a rescue that included cave divers began.

The group was trapped more than two kilometers into the eight-kilometer-long cave system. They sheltered on a small ledge, ten meters above the water level. On the first day, rescuers reached but could not evacuate them. They gave them food and blankets to survive until the waters receded.

After two days, everyone made it safely out. This was the first incident of its kind in the popular cave.

The Krizna Jama cave lies in Slovenia's Loz Valley. The karst cave has more than 20 underground lakes, which can be navigated by boat. The cave also features more than 60 different animal species.

A cave bear’s skeleton can be seen there too. Aleksander Skofiz first discovered the bones in 1847, and Ferdinand von Hochstetter started the excavation in 1878. The remains are the richest of its kind in Europe.

Archaeological remains up to five thousand years old add further to the interest. People didn’t live there but used the cave. There are daily guided visits into this popular tourist attraction.

When we’re not outdoors, we get our adventure fix by exploring social media and the web. Here are some of the best adventure links we’ve discovered this week.

Graham Zimmerman’s Close Call: An excerpt from Zimmerman's new book. Zimmerman and Clint Helander made the first ascent of the west face of Mount Titanic in the Revelation Mountains, Alaska. Days later, Zimmerman was ready to tackle another climb, Helander wanted a few more days of recovery.

A frustrated Zimmerman skied off without his partner, irritated that he would have to wait. Eventually, he saw sense and chastised himself for leaving them both in an unsafe situation. But before he could return, the ice below gave way and trapped him in a crevasse.

75-Year-Old Completes International Appalachian Trail: Will French started thru-hiking in his 50s. He fell in love with the camaraderie he found and the feeling of being on the trail.

In 1998, French heard about the International Appalachian Trail. It does not have a set route but crosses 22 countries following a rough trail across the ancient Appalachian-Caledonian Mountains before the continents split. French started in 2009 and finished 14 years later.

Falling ill 1,000m underground

1,000 Meters Below: Mark Dickey is one of the most experienced cavers in the world and has helped with many rescue missions. This September, he himself needed rescue.

Dickey was 1,000m below the surface in Morca Cave, Turkey. Twelve hours from the surface, he fell ill. Blood in his stool and vomit indicated internal bleeding. His fiancé and friends tried to pull together a rescue mission.

Why We Kick Cairns: Hikers build piles of rocks on trails and mountaintops -- sometimes as navigational markers, sometimes as I Was Here graffiti. In this podcast, Justin Housman and Stephen Casimiro discuss the origins of cairns, their environmental impact, and their opinion on kicking them over.

The Original Mountain Marathon Heads to Wales: This year, the two-day Original Mountain Marathon took place in north Wales. Armed with a map of the 150 sq km competition area, 1,500 competitors flocked to the mountains.

They faced poor visibility, rain, slippery rock, high winds, steep uphills, and scree. Here, competitors and organizers reflect on the event and the move to Wales.

Adventure weddings

Weddings at the Edge of the World: Adventure weddings are a surprising addition to the world of backcountry travel. For some couples who share outdoor pursuits, it seems like the perfect option.

One couple heads to Everest to say, "I do." Another pair has the ceremony at the top of a mountain and proceeds to ski down in their wedding finery, with all the guests in tow.

Comical Complexities of a Surf Lineup: At first glance, the rules of a surf lineup seem straightforward. In reality, there are many unwritten rules, which can change depending on where you are and who you are around. One of the difficulties of surfing is figuring these out when you have been thrown into a new surfing lineup.

Evan Quarnstrom speaks about his memorable lineups, the micro-calculations he made, and the comical side of bizarre situations.

Non-sight Ascent of Destiny: Blind climber Jesse Dutton has made the first non-sight ascent of Destiny E2 5c on Lundy Island. It is one of the hardest climbs he has completed.

Dutton's wife, Molly, was his sight guide for the challenge. Here he discusses the climb, how his mind wandered to philosophy, and how he applies this to climbing.

Mark Dickey has emerged from the Turkish cave that almost killed him after “one hell of a crazy, crazy adventure.”

Outlets worldwide reported live as rescuers removed a stretcher-bound Dickey from the mouth of Morca cave on Sept. 12. The 40-year-old caver had experienced an attack of internal stomach bleeding that marooned him 1,000 meters below the surface for days longer than planned.

Over 160 people participated in the elaborate and financially demanding rescue that followed, the United States’ National Cave Rescue Commission (NCRC, where Dickey works as an instructor) reported. Teams from Turkey, Hungary, Bulgaria, Italy, Croatia, Poland, and the U.S. joined the effort. Crowdfunding campaigns rallied tens of thousands of dollars in support.

Internal bleeding

Dickey’s fiancee, fellow caver and paramedic Jessica Van Ord, also aided in the rescue. She described his abdominal symptoms on Good Morning America.

"You always hear the term black tarry stool," Van Ord told GMA’s Michael Strahan in a Wednesday interview. "When I saw it, I knew immediately we were dealing with internal bleeding. Mark needed to first get back to camp safely. Unfortunately, under his own power because we were just a small group at that time. We just had to keep our eyes on what was happening and make sure we were planning and acting appropriate."

Teams completed Dickey’s extraction from the cave around 12:37 am local time on Tuesday, according to the Turkish Caving Federation.

The NCRC commented that it takes around 15 hours for a healthy, experienced caver to ascend to the surface from the camp where Dickey was injured (called “Camp Hope”). For Dickey, it took more than 50 hours.

Rescuers had prepared the passage extensively, working in a series of seven teams in a relay setup at varying depths. The groups established continuous communication lines from the surface down to Camp Hope, reinforced rigging, and even blasted tight passages to make sure Dickey’s stretcher could pass through.

As of Wednesday, Dickey remained hospitalized in the southern Turkish city of Mersin for further observation, ABC reported. Turkish authorities described his condition to the outlet as “good.”

“The global cooperation to get Mark out of this deep, deep cave is amazing,” NCRC National Coordinator Gretchen Baker said in a statement, describing the challenges as “extremely difficult.”

Dickey’s parents have widely expressed their relief and gratitude.

Deep in the chambers of a renowned Turkish cave, an American explorer was in trouble.

Mark Dickey, 40, came down with sudden "stomach bleeding" while exploring southern Turkey’s Morca Cave in late August, the Associated Press said in an early report. Dickey, an experienced caver, was taking part in an expedition that included several others when he fell ill.

Dickey and the group had descended over 1,000 meters into the cave when he became unable to return to the cave’s entrance.

Rescuers, including a Hungarian doctor, rushed to the scene with help from the Turkish government. In a video shot on site, Dickey says he received treatment that “saved [his] life.”

“I want to thank everyone that’s down here, and thank the response of the caving community. The caving world is a really tight knit group, and it’s amazing to see how many people responded on the surface,” he says in the clip.

Dickey may be in the cave for weeks

He attributed his salvation to the quick response and critical attention he received. However, the final outcome remains unclear. He and the rescue teams will need to spend “days or weeks” inside the cave system while he recovers enough to squeeze through multiple body-sized passages on the way out.

USA Today has rendered a detailed report of the rescue operation, which the European Cave Rescue Association (ECRA) is organizing. Several teams have divided the cave into seven segments. A Turkish team is stationed from zero to 180m. A team from Hungary takes the next section, from 180m to 360m, then a Polish team takes over down to 500m. Two teams from Italy are covering the area down to 715m.

Finally, two teams from Croatia and Bulgaria are responsible for the distance from there to Dickey’s location.

The task has proven coordinately and financially demanding. A GoFundMe campaign had raised over $50,000 for the effort as of this writing.

The latest information from the ECRA, issued Friday morning, indicates that all teams are making efforts to ensure “transport to the surface can begin soon.”

Morca is Turkey’s third-largest cave system. Nestled in the Taurus Mountains near Eremenek Baraji, an alpine lake, it plunges to 1,276m.

Dickey is Chief of the New Jersey Initial Response Team, a volunteer group that specializes in cave and mine rescue, and is an instructor for the National Cave Rescue Commission. Whether official work in either capacity led to the current incident is unclear.

Beatriz Flamini might be the Michael Jordan of living in a cave.

In a strange and personal adventure, the 50-year-old Spanish athlete entered a cave 70 meters below the Earth in Granada, Spain, on November 21, 2021. She was 48 at the time.

Today, she finally exited her subterranean home and shared her secret project of isolation with the rest of the world, El Mundo reported. So what's her take on the often debilitating impact of living without sunlight or any human contact for 500 days?

"I didn't want to leave," she said at a press conference (translated from Spanish), and there wasn't "any bad moment."

For that statement alone, I'm ready to accept Flamini as possibly the most psychologically resilient person on the planet. Though monitored by scientists, she spoke to no one and received no information from the outside world. Food and water were left for her without any physical contact.

Her time underground is likely a world record for voluntary cave living. Known mostly for climbing and alpinism, Flamini spent her time exercising, plus knitting, painting, exercising, and reading 60 books by headlamp. She also made a video diary for the documentary, and drafted a book about the experience that she plans to publish.

She views her cave tenure as "excellent" and "unbeatable," according to the BBC.

"There was a moment when I had to stop counting the days," she said.

(Below is her last Instagram post from November 2021, a month before entering the cave and giving up all communication.)

Ver esta publicación en Instagram

Balance off, hallucinations on

When her team came to escort her out of the cave on Friday, Flamini believed that something dire had changed their plans. From her perspective, she'd only been underground for "between 160-170 days."

"I've been silent for a year-and-a-half, not talking to anyone but myself," she said. "I lose my balance, that's why I'm being held."

There's no doubt much more to learn about Flamini's adventure, from the "auditory hallucinations" to the invasion of flies that left her covered in the tiny bugs.

"I'm not going to say more because if I do, you won't read the book," Flamini said.

You probably already know the story.

In 2018, 12 juvenile members of the Wild Boar soccer team, along with their 25-year-old assistant coach, became stranded in the Tham Luang Nang Non cave system in Thailand. The group was exploring there after practice when an early-season rainstorm caused water levels to rise dramatically, forcing the team to retreat to a high cavern far from the cave entrance.

Turbid, fast-moving water, low visibility, and narrow, difficult-to-navigate passages hampered the subsequent rescue. Divers fully expected most, if not all, of the soccer team to die in the attempt.

A miraculous rescue

Despite those odds, the rescuers successfully extracted all 12 children and their coach. The story inspired a documentary by Jimmy Chin and a dramatic adaptation by Ron Howard, among other projects. With the recent release of these films, the event is back in the public consciousness, prompting some to ask the question, "What can we learn from this unprecedented success?"

Andrew Petrosoniak, an emergency physician and trauma team leader at St. Michael's Hospital and Assistant Professor in the Department of Medicine at the University of Toronto, is such a person. In a viral Twitter thread, Petrosoniak breaks down the rescue and looks for takeaways that could aid first responders in future situations.

The Thai Cave Rescue might be one of the most impressive examples of high stakes decision making & human performance in recent memory.

The exact details of what happened are truly amazing and warrant a deeper dive.

What can we learn from this unbelievable success story?

1/ pic.twitter.com/CACR7OJ7Ka— Andrew Petrosoniak (@petrosoniak) December 16, 2022

A few reminders

Before we get to Petrosoniak's takeaways, it's worth remembering just how difficult this rescue was.

It wasn't even clear that the soccer team was alive until they'd been missing for more than a week. Divers plunged again and again into frigid, muddy water, exploring chamber after chamber with increasingly grim expectations. When British divers John Volathen and Rick Stanton found the group huddled on a narrow shelf above the rising floodwater, hungry but alive, it was a surprise to all involved.

But finding the Wild Boars and their coach was just the beginning of the problem. Reaching the chamber required more than three hours of travel (one way!) through some of the most hellacious, dangerous conditions a diver can face. So how to get the boys and their coach to safety in circumstances that gave world-class divers pause (and had already claimed the life of a Thai Navy Seal?)

On the bleeding edge of the monsoon season proper, rescuers realized that the children, untrained as divers, would not be able to avoid panic if rescuers tried to assist them underwater back to dry land. Instead, they made the unprecedented decision to anesthetize the group and ferry them out one at a time over the course of several days.

The strategy carried immense risks: the anesthetic had to be re-administered periodically throughout the dive, and asphyxiation was a constant possibility. Rescuers could not monitor vital signs electronically after administering the anesthetic. Instead, they had to observe air bubbles to ensure the children were still breathing.

Moving an unconscious human body through the water is no easy task, even under the best of circumstances. Add in tight passages and near-zero visibility, and it becomes nearly unthinkable. And yet, the team achieved total success.

Five key takeaways

In his Twitter thread, Petrosoniak views the events through his unique perspective as a trauma expert. To summarize his conclusions:

- The situation was nearly impossible.

- Rescuers did not let that fact paralyze them into inaction.

- After thinking outside the box, the only viable solution was still frighteningly dangerous and prone to failure.

- Rescuers mitigated what risk they could and then proceeded with the rescue.

- Success was a combination of skill, teamwork, physical stamina, correct application of mental tactics, and luck.

Petrosoniak begins by stating that rescuers acknowledged when they had to act — they did not let the circumstances paralyze them into inaction. Freezing up is the hidden third response behind "fight or flight," and it's quite common in complex or traumatic situations. It takes training and experience to overcome it, two things the rescuers luckily had in spades.

A crazy idea was the key to success

The doctor also notes that sometimes standard solutions are inadequate to solve extraordinary problems. The rescue team briefly considered far more typical options, such as attempting to keep Wild Boars alive until the water could recede, drilling a rescue tunnel, or training the children in basic diving techniques. For various reasons, rescuers rejected all of these proposals before landing on the only viable, if extreme, option.

"Crazy ideas sometimes are the key to success," Petrosoniak concludes.

Managing personal mental state is a crucial tactic in extreme situations. One challenge the rescue divers faced was the knowledge that the children in their care could — and likely would — die at any moment during the swim to safety.

The solution? A technique called cognitive reframing.

"The rescuers considered each child as a package. It removed the emotion and helped reduce stress in an incredibly stressful situation," Petrosoniak writes.

Pre-mortem

Petrosoniak concludes his thread by remarking that the rescuers conducted a pre-mortem, allowing themselves to consider worst-case scenarios and then creating mitigation strategies for those scenarios. It's a technique that's been around for millennia (the Roman Stoic philosophers called it premeditatio malorum.)

Such a strategy can be counter-intuitive for high-performers that have trained themselves to visualize success, and yet Petrosoniak identifies it as a crucial element in the rescue mission's positive outcome.

Finally, Petrosoniak acknowledges that despite world-class skills and correct decision-making at every point in the rescue, getting every child out alive required a certain amount of luck. It's an important point to make, as it highlights the somewhat random nature of disasters and disaster management.

You can read the entire thread here. It's an interesting perspective on the nature of rescue attempts and is applicable to adventurers of all stripes.

Marion Smith, a caver with 8,291 separate explorations to his name, died on Nov. 30 of congestive heart failure and chronic lymphocytic leukemia, according to The New York Times. He was 80.

Smith was born in Fairburn, Georgia in 1942, and spent a lifetime exploring the southeastern United States' famous limestone cave systems. According to the Times, Smith was a member of a team of cavers that discovered a previously unknown 106m-tall, 1.8-hectacre chamber in East Tennessee in 1998. The chamber is part of a cave system known as Rumbling Falls. Smith was its principal explorer, according to a 2002 Sports Illustrated profile.

Marion Smith, a relentless, irascible subterranean explorer who...visited more caves than anyone else in human history, died on Nov. 30. He was 80. https://t.co/rp46almbZc

— The New York Times (@nytimes) December 17, 2022

After retiring from a historical research position at the University of Tennesee in 2000, Smith's caving escalated. His hyperactivity culminated in 2014, with 335 cave visits that year. Smith was 71 at the time.

That was also the year that Smith fell into a pit and became pinned under a boulder for nine hours. After rescue, Smith checked himself out of the hospital and returned to the Van Buren County cave for more exploration — all on the same day.

"This incident, all it did was screw up my plans for the weekend," Smith told the Chattanooga Times Free Press shortly after 50 volunteers helped free him from the boulder.

Smith's caving frequency may have peaked in 2014, but he continued exploring until the last years of his life.

“Every day, he wanted to create an adventure,” Chuck Mangelsdorf, Smith's friend and fellow caver, told The New York Times.

A man of many talents

Smith also continued his penchant for historical research well past his retirement. In 2010, the caver partnered with historians at Volunteer State Community College in Gallatin, Tenn., to document Civil War-era graffiti in Mammoth Cave, Kentucky. He was also one of the world's foremost experts in the historical mining of saltpeter, a critical ingredient of gunpowder.

"Even if I'm physically impossible to go in a wild cave, surely I can be put in a wheelchair and wheeled to a commercial cave," Smith told the Chatanooga Times Free Press in 2014. "And if I can't be sitting up in a cave, surely they can put me on a stretcher and wheel me into one."

Smith is survived by his partner, Sharon Jones.

A mass of ice fell from the ceiling of an ice cave in Argentina, killing a Brazillian tourist on Nov. 2, reports Cumbres Mountain Magazine.

The cave, known as Jimbo Cave, is accessible only by a nine-kilometre walk within a glaciated area of Argentina's Tierra del Fuego National Park.

The tourist, along with his dog and several other people, walked by a large sign reading "Alert: Do Not Enter" as they entered the cave.

Moments later, a block of ice fell from the ceiling and landed on the Brazilian visitor. Another tourist, standing back from the entrance, captured the event on video. Different outlets have variously reported the total number of tourists in the party as six or seven.

Un grupo de turistas de Brasil ingresó a una cueva de hielo en Ushuaia, pese a carteles que indicaban la prohibición. Un trozo enorme de hielo cayó del techo, causando la muerte a uno de ellos. El fatal instante quedó registrado en video.https://t.co/En5XjMtcMQ pic.twitter.com/cNTp7MD9I9

— cumbresmagazine (@CumbresMagazine) November 3, 2022

A search and rescue team based in the nearby city of Ushuaia arrived several hours later, according to Cumbres. The identity of the tourist is currently not public knowledge, though he reportedly had "no documentation among his belongings".

Cumbres also reports the man was approximately 30 years old and was "traveling alone around the country".

An investigation, including an autopsy and collection of witness statements, is ongoing.

Off-limits since 2021

National Park officials have prohibited entry to the Jimbo cave since 2021. That's when scientists from the Austral Center for Scientific Research first raised flags about the cave's stability.

"Entry is forbidden because ice and rock can fall from the roof of the cave," police official Cristian Armani told Reuters. "Cueva de Jimbo is at the foot of the glacier, it was formed naturally from rock and ice and gets eroded by the wind and thawing temperatures."

Ushuaia is Argentina's southernmost city, located some 3,070km south of Buenos Aires.

In 2007, a group of cave divers began probing an underwater cave in central Sweden’s Jämtland Mountains. When they began, they had no idea they were going to discover Sweden’s largest underwater cave system. Fifteen years later, they are still exploring it. They were there last week.

Cave diving is notoriously dangerous. The handpicked team of 20 had to cope with deep snow, ice, and freezing temperatures. And that was even before entering the cave.

Their 13th expedition into the caves began on March 25. The only years they didn't go were the pandemic years of 2020 and 2021. This year, they split into two teams and focussed on separate caves: Bjurälvsgrotten and Festins.

Each winter, the challenges are similar. The first is just getting to the flooded caves. No roads or villages exist nearby. They must snowmobile to the northwestern Jämtland range. They only dive in winter because at other times of the year, vehicles are banned to preserve the fragile vegetation in this national park. Also, the current through the caves is too strong in summer.

Once they get there, they must first shovel out metres of snow, plus debris from the previous summer, blocking the entrance. Then they make reconnaissance dives to set up equipment and leave spare air tanks in the areas that they have already mapped.

The entrances to the caves and the passages within are so narrow that the equipment must be side-mounted. The cave system has many sumps. Sumps are flooded areas within the cave that make exploration by dry cavers impossible. As of 2016, they were diving in Sump 5.

In sump diving, cavers must navigate tight passageways and vertical drops, often crawling and dragging equipment while wearing scuba-type gear. The water temperature hovers around 0°C, so all divers wear drysuits. Drysuits are not known for their streamlined nature.

On the third day of this year's expedition, the teams made it into both caves. Bjurälvsgrotten had a much more challenging entrance. Every diver had to make a 10m vertical descent inside a waterfall before disconnecting from the ropes. Once inside, they needed to shovel to improve accessibility.

Throughout the week-long expedition, diving at Bjurälvsgrotten was a struggle because of the heavy flow even at this time of year. They were more successful in Festins. After five days, they discovered virgin caves and were able to complete 30m of surveyed line.

"Thirty metres doesn’t seem a lot," they explained, "but it requires quite great effort [to map] every metre of virgin cave.”

They then surveyed a further 30m of line. At the end of their expedition, both teams did some preliminary diving at Meandergrottan, the lowest known outlet of the Bjurälven River. They hope to explore that region further in the future.

Expedition Bjurälven is named after the Bjurävlen Valley where the exploration is taking place. That whole region is awash in caves. For many caves, records of exploration date back to the mid-20th century. Researchers with the expedition believe that all of the caves in the area may connect into one giant cave system.

So far, their theory has stood up. So far, they have discovered 2.43km of linked passageways and caves, making it the longest underwater cave in Sweden. No one knows how much further it stretches. Finding that out is a job for years to come.

In the early afternoon of November 6, 2021, 38-year-old George Linnane of Bristol took a 15m fall in Wales's Ogof Ffynnon Ddu cave system. He suffered a broken leg, sternum, and cracked jaw — serious but not life-threatening blows.

But extracting him from the UK's deepest cave would prove slow, technically challenging, and exhausting. Located in Brecon Beacons National Park, Ogof Ffynnon Ddu reaches 274m below ground and is 50km long.

UK cavers to the rescue

His partner quickly summoned cave rescuers. Steve Thomas's team, the first on the scene, knew that they'd need all the backup they could get. In a statement to the BBC, the Derbyshire Cave Rescue Organization explained the difficulty:

Moving through a section of passage for an uninjured, fit caver can be a challenge — squeezing through things, climbing on things, wading through water, and so on — but it can be done.

But when people are immobilized they have to be put on a stretcher and brought out by a team of 10 or so people.

"Imagine everyone trying to maneuver the stretcher through holes only big enough for one person to go through. It's a very slow process — 10 to 20 times longer than normal.

And so Thomas's team issued a UK-wide call to action. By mid-Monday, nearly 300 volunteers from 16 cave rescue teams, dispatched from as far as 300km away, filled the rescue lineup at the Brecon Beacons.

It became the longest rescue mission on Welsh record. From Saturday evening through Monday, teams from all over the UK worked in shifts. The throngs of volunteers wheedled equipment, food, and themselves through Ogof Ffynnon Ddu's labyrinthian cradle.

On Monday night, after 54 hours of work and complicated logistics, George Linnane and many of the recovery volunteers emerged from the abyss onto higher ground. The weather was too foggy for a medical aircraft. So a Land Rover taxied Linnane to the nearest hospital for treatment.

The rescue became a story of camaraderie and cooperation far greater than its component parts. "This was a completely voluntary operation, nobody gets paid...and the cooperation between the teams and the standard to which everybody worked was absolutely 100%," rescuer Steve Thomas remarked.

Extra credit: the "Cave-Link"

According to rescue leader, Paul Taylor, teams below ground were able to communicate with those above through a "Cave-Link" system. The engineering marvel allows people to send text messages through water particles within the limestone formation to a control room, independent of any cables or wiring.

The Annamites don’t boast any towering snow-capped peaks. They don’t even feature the highest mountain in Vietnam; the “roof of Indochina” (3,147m Fansipan), sits much further north, near the Chinese border. But the Annamites remain a wild, underexplored range, perfect for those looking for a unique challenge.

The Annamites stretch 1,100km along the spine of Vietnam and Laos, dotted with dramatic limestone outcrops, 2,000m peaks and countless caves. Internationally, the area is best known by another name: The Ho Chi Minh Trail. The North Vietnamese Army used this complex web of paths to move fighters and supplies into southern Vietnam during the war. These hidden trails wove through dense rainforest and rugged passes, prompting the United States' own National Security Agency to label it “one of the great achievements of military engineering of the 20th century.”

The United States did its best to relegate the achievement to a historical footnote. Planes dropped some two million tonnes of explosives on the trail between 1964 and 1973. The U.S. threw everything at the supply line: cluster munitions, defoliants, napalm. It even attempted cloud-seeding to extend the monsoon season. Despite this ferocious bombardment, the supply line remained unbroken, a testament both to the hardiness of those working the trail and to the unique topography of the Annamites themselves.

Since the war, the range has slipped back into relative obscurity. Tourists visiting Vietnam take motorbike tours of the Ho Chi Minh Trail, but these barely touch the real routes. Instead, they take in key battlefields and strategic cities such as Huế and Đà Nẵng. The original trails and hideouts lurk in the region’s most inaccessible spots, including a handful of the highest peaks.

The highest mountain in the Annamites, 2,819m Phou Bia, lies on the edge of the range and was not part of the Ho Chi Minh Trail. Also the highest peak in Laos, it was used by guerrillas fighting for the other side of the conflict. Here, the CIA paid ethnic Hmong to counter North Vietnamese forces throughout the Annamites. Phou Bia is remote, covered with dense jungle, and officially off-limits due to military restrictions.

Phou Bia may be closed, but plenty more options exist for serious hiking. Unfortunately, exploration is complicated. There are obvious difficulties: monsoon rains, thick jungle and limited transportation. The more unusual difficulties include an unknown amount of unexploded ordnance from the war and thousands of wire traps for exotic animals, used both by local poachers and international wildlife crime syndicates.

One of my most nerve-wracking moments in Vietnam came deep into an eight-hour jungle hike when I stumbled across a fully camouflaged man, armed with a large, silenced assault rifle. I was armed with a rather less intimidating weapon, a telephoto lens. It occurred to me that we were probably both looking to shoot the same animals. Fortunately, he seemed as surprised as I by the encounter, and I slipped away without making small talk…

Whether the Annamites biodiversity can survive this rampant poaching remains to be seen, especially with so little available data and almost no government protection. But efforts are being made. The recent discovery of several new species may spur conservation efforts. The Vietnamese government has already made excellent progress with new forest reserves designed to protect habitat of one of these discoveries, the saola or so-called Asian Unicorn. One of the world’s rarest large mammals and one of the last discovered, the saola is endemic to the Annamites and can only be saved with significant investment.

Several national parks have recently formed on both sides of the range: Bạch Mã, Phong Nha Kẻ Bàng, Vũ Quang and Pù Mát in Vietnam and Dong Amphan and Nakai-Nam Theun in Laos. However, most of them are only theoretical tourist sites. Aside from Phong Nha Kẻ Bàng, they have extremely limited infrastructure and receive only a sprinkling of intrepid visitors a year.

Phong Nha Kẻ Bàng is the exception, thanks to its astounding array of caves. This Kingdom of Caves became a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2003 and features at least 300 caves, of which 30 are open to the public. The more accessible ones have become a huge draw; some three million tourists, including 50,000 foreigners, visited the park in 2015.

But the 900-square-kilometre park likely still hides some spectacular secrets. The jewel in Phong Nha Kẻ Bàng’s crown was only “discovered” by the international community in 2009. Quite how the largest cave in the world (by cross-section) remained hidden for so long is testament to the rugged, challenging landscape. A local boy, Hồ Khanh, first glimpsed the cave in 1991, but the roar of water and wind put villagers off from exploring its interior.

Years passed, and it was not until 2009 that Khanh, now an adult, was able to retrace his childhood steps and lead a Vietnamese-British team to the yawning chasm, now known as Hang Sơn Đoòng, that he had found nearly two decades earlier.

"The cave is very far out of the way. It's totally covered in jungle, and you can't see anything on Google Earth," caver Adam Spillane explained afterwards. It was immediately apparent that Sơn Đoòng would be one of the largest caves in the world. The first expedition team made it over 3.5km into its vast system before a colossal 60m limestone wall, appropriately nicknamed the Great Wall of Vietnam, stopped them.

A return expedition the following year managed to get beyond this obstacle. The team reached the end of the cave passage and confirmed its gargantuan dimensions. All together, Sơn Đoòng measures more than four kilometres long, with a colossal middle passage 100m wide and 200m high. To put this into perspective, a Boeing 747 could comfortably fly through it, or if you prefer, you could throw in the Great Pyramid of Giza with 50m of space to spare. National Geographic described the discovery as “like finding a previously unknown Mount Everest underground.”

Incredibly, more underground systems have recently come to light. Just last week, the British Cave Research Association announced the discovery of 12 new caves in the province, an astonishing number given the wealth of surveys conducted in Phong Nha Kẻ Bàng in recent years. With so much still unknown within the Annamites' most developed park, it’s hard not to get excited about what other discoveries, and adventure possibilities, await in this oft-overlooked mountain chain.

In this film, set deep in the jungle of the Nakanai Mountains in Papua New Guinea, a 15-member French spelunking team searches for undiscovered caves and underground rivers. They start at the finish: a resurgence called Wara Kalap (Papuan for leaping water), spewing hundreds of gallons of water from its mountain jaws every second.

To find the source of the resurgence, they establish a base camp about 400m above sea level with the help of local indigenous people. From here, they begin hacking through thick jungle in search of openings that may lead them to their goal.

After three weeks of dead ends, the group decides to move up to 1,000m. Ensue two more weeks with no results, before they find two small entry points. These appear insignificant, but a strong rising air current gives the team hope that they lead somewhere.

They dive almost 700m below the surface and two kilometres from their entry point, probing in the dark for the collection basin of a significant underground river.

The film shows both their underground search and the above-ground views of the world's most remote and virgin equatorial rainforest. Despite the extreme conditions, the group's curiosity and sense of adventure allow them to follow their passion to fulfillment.

Since 2004, Scottish filmmaker Paul Diffley has been carving out a niche for himself making films about Britain's most acclaimed climbers. A chance meeting a few years ago at the Kendal Mountain Film Festival with Steph Dwyer, coordinator of the Ario Caves Project, convinced Diffley to momentarily turn his viewfinder away from mountains and go in pursuit of his first-ever caving film.

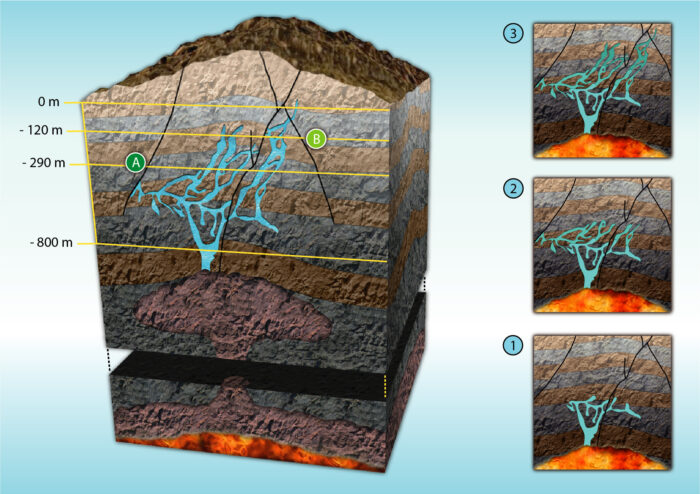

Shot over two summers in 2016-17, The Ario Dream tells the story of cave exploration in the Picos de Europa mountains in northern Spain, which is believed to harbour a system more than 1,800m deep. If true, this would make it the deepest in Europe and one of the top five deepest caves in the world.

A digital cave survey showing an overview of all currently explored and mapped caves within the Ario bowl. They range in depth from several hundred meters to nearly 1,000 meters. Screenshot by Ario Caves Project.

Oxford University's Caving Club (OUCC) was the first to recognize the area's potential, and every year since 1979, an international crew of cavers has searched for promising new entry points, thrutching their way through meandering rift passages and descending unexplored shafts.

In any cave, one obstacle can immediately halt progress: submerged passages, known as sumps. In Diffley's film, he delicately captures the skill and commitment of two cave divers, Paul Mackrill and Tony Seddon, as they attempt to link up the cave known as Sistema Verdelluenga (C4) with another named 2/7, which was explored 20 years previously. The only obstacle separating these two subterranean chambers is an underwater passage of indeterminate length. Their one certainty is the risk they face when diving into this unknown territory.

Paul Mackrill conducts his pre-dive checks before entering the sump separating caves within the Ario system. Photo: Paul Diffley

The film shows the contrasting calmness and tension as the divers methodically prepare to enter the sump. Interspersed throughout these primary scenes, archival footage of earlier explorations, interviews with both the divers and with the authors of a book documenting the earliest forays into Ario's depths, show what it takes to pioneer a new cave.

The Ario Dream brings to the surface a world of extreme adventure that -- unlike mountaineering, say -- few of us are familiar with and still fewer would dare to do.